By Kevin M. Hymel

Private First Class Bob Wolf rode in a jeep along an exposed hill in Germany’s Ruhr Valley when he heard an enemy artillery round screeching toward him. He was out with his battalion operations officer, looking for a place to set up a forward command post. Wolf hit the ground as the shell exploded and fragments tore through the air. A chunk landed next to him and, without thinking, he reached for it before the heat from the smoking hot shard caused him to pull his hand away.

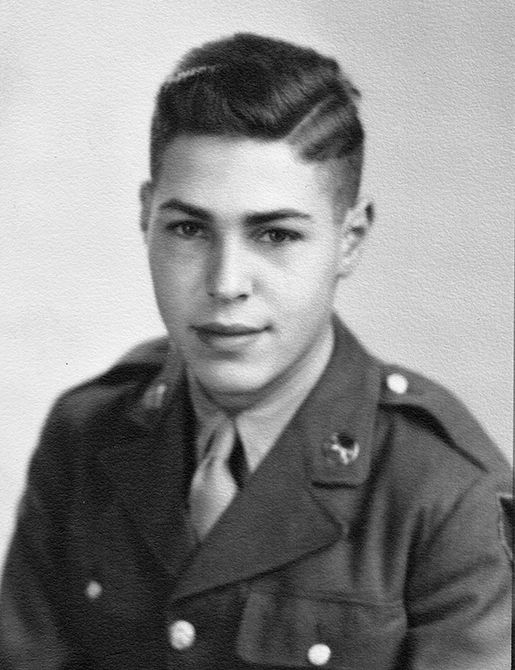

Wolf, an intelligence staffer with the 86th Infantry Division’s 1st Battalion, 343rd Infantry Regiment, wore dog tags around his neck with the letter “H” for “Hebrew.” Dangling with his dog tags was a mezuzah, a small tube with a piece of parchment inscribed with Hebrew verses from the Torah, which further identified his Jewish faith. “In retrospect,” he later reflected, “one wonders how stupid anybody could have been to advertise to the Germans who the Jewish soldiers were.”

By April 1945, the war in Europe was winding down. The great battles of Normandy, the Falaise Pocket, the Netherlands, and the Bulge had all happened the year before. The Rhine River had been crossed in late March. Now the Western Allies were aiming to knock out the German industrial area in the Ruhr, while the Soviets battled for Berlin.

Yet the war was still deadly—German soldiers, looking to draw blood as the Third Reich crumbled, still fought. And the American Army still needed soldiers to fight them. Wolf’s division had been slated for amphibious operations in the Pacific, but there were so many American casualties at the Battle of the Bulge that the Army rerouted them to Europe instead. “We would have been ready for Okinawa,” Wolf said, “but we got turned around.”

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, igniting the war in Europe, Wolf was only 14 and living in New Rochelle, New York. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, he was 16 and living in Miami, Florida, working on an 11th grade physics project. But the draft age was 21. “It never occurred to me that I would be in the war,” he said.

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, igniting the war in Europe, Wolf was only 14 and living in New Rochelle, New York. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, he was 16 and living in Miami, Florida, working on an 11th grade physics project. But the draft age was 21. “It never occurred to me that I would be in the war,” he said.

“I was going to be drafted in early September,” he remembered, “but the Army made me an offer that was difficult to refuse.” On August 24, 1943, the day before his 18th birthday, he joined the Army’s Enlisted Reserve, which would allow him to complete his first semester at Yale and ensure his entry into the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), which sent promising enlistees to universities to learn skills such as engineering, medicine, and foreign languages.

Wolf reported for duty at Fort Devens, northwest of Boston, Massachusetts, on November 5, 1943—the same day the War Department decided to dissolve ASTP. The war required soldiers, not scholars. Unaware of his changed prospects, he reported for 17 weeks of basic training at Fort Benning (Fort Moore as of 2023) in Georgia. While on field exercises in January, 1944, he came down with pneumonia and then German Measles. When he was finally released from the hospital, he had to join a different training company to complete his training.

After basic, Wolf and his new buddies were sent to Camp Livingston, in Alexandria, Louisiana, to join the 86th Infantry Division, under the command of Maj. Gen. Harris M. Melasky. The division had been gutted of its riflemen, who were needed overseas, and was now filled with former ASTPers, former Army Air Forces cadets, and coastal artillerymen. “They were well-motivated people with very good morale,” said Wolf wryly.

While Allied forces under General Dwight D. Eisenhower assaulted the beaches of northern France on June 6, 1944—D-Day, Wolf, assigned to Company C, of the division’s 343rd Infantry Regiment, trained in central Louisiana’s Piney Woods. With Wolf’s ability to speak German, he was eventually transferred to the 1st Battalion’s S-2 Intelligence Section. “That made my mother feel really good,” he said. “She didn’t know it meant scouts.”

The Intelligence Section consisted of five other privates and a sergeant. Wolf remembered them as an oddball bunch. One soldier named Robbie hailed from Bangor, Maine, where his parents ran a coal and ice business. Another, Tony Tappen, was the son of an English diamond merchant who brought his family to the United States at the start of the war. Then there was John DeLorean, who often wore aviator glasses (and would later go on to form his own car company). “He was really a bad boy,” Wolf recalled. DeLorean also had his own way of doing things. “That was the first time I ever heard of marijuana.”

Wolf’s best friend, however, was Jerry Shpall, a soldier from Denver in E Company. “He was the extravert and I was the introvert,” said Wolf. “He led me astray.” The two enjoyed Sunday dinners with local families, or drinks at local bars. Sometimes they rented a room at Alexandria’s Hotel Bentley. “We could pack 10 people in a room.” The experience taught Wolf his limits. “I learned my capacity for beer, whisky, and wine,” he said. “Beer on the base was 3.2-percent alcohol beer and you had to drink more than you could stomach to get drunk.” For Passover, Wolf and Shpall got passes and attended a community Seder at the local temple. “Jerry’s family was orthodox and my family was not,” he recalled, “so the second night we went to the Orthodox synagogue.”

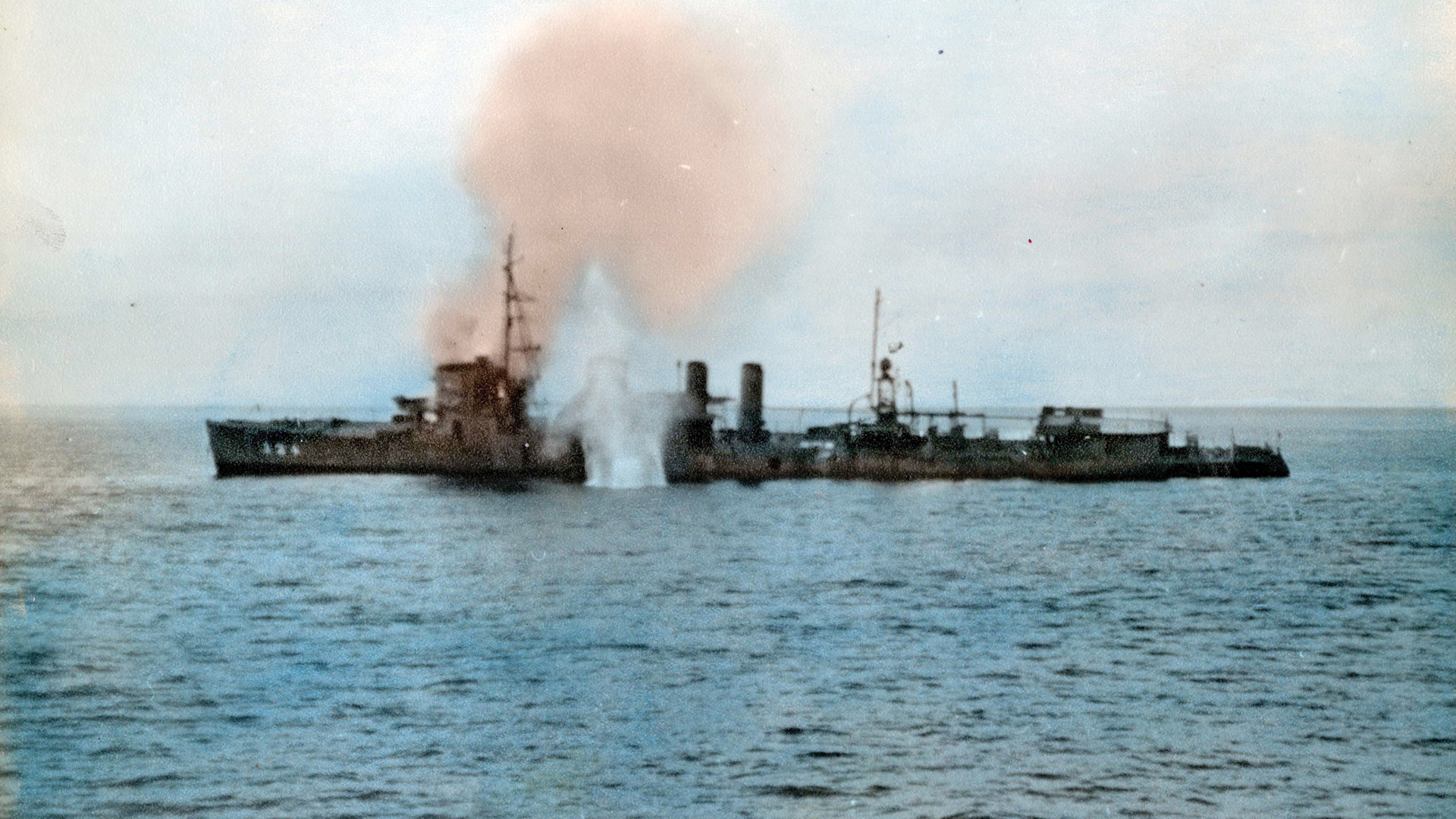

After training at Camp Livingston, the entire division shipped out for Camp San Luis Obispo, California, for amphibious training. They practiced climbing down cargo nets into Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVP) boats, while the Intelligence Section trained in rubber boats. It was during this training in December of 1944 that the Germans launched their winter offensive in the Ardennes Forest in Belgium and Luxembourg. Instead of the Pacific, the division sailed from Boston for Le Havre, France, on a converted passenger liner. During the voyage, soldiers took turns Topside duty searching for German U-boats was “cold,” Wolf recalled.

The division reached France in early March and assembled at Camp Old Gold, one of the nine camps named after cigarette brands in Normandy. After about two weeks the men headed out in 40-and-8 trains, so named because each car could hold 40 men or 8 horses, which took them to the outskirts of the German city of Cologne. “The city center was bombed out,” Wolf said, “but there were some mansions a mile back on a leafy street.” Wolf helped set up the battalion headquarters in a mansion, where he kept the battalion journal and worked as a “gofer.”

One night, Wolf spied a strange group of Americans wearing all sorts of uniforms walking into battalion headquarters. Looking back on the incident today, he realized they might have been the Ritchie Boys, German and Austrian immigrants, many of them Jewish, who were trained at Camp Ritchie, Maryland, and served as U.S. Army intelligence soldiers. “Whoever they were, they were obviously a very peculiar bunch.”

Soon after, Wolf went into Cologne and discovered its underground wine caves. “There was still wine there!” he recalled. Since no one had brought a corkscrew, Wolf and his comrades innovated. “I remember breaking off the neck of a bottle on the wine racks,” he said. He got sick from the wine.

After their stint in Cologne, on April 5, the 86th Division packed up, crossed the Rhine River, and joined General Courtney Hodges’ First Army, which at that time was squeezing the Ruhr Pocket from the south. Both the American First and Ninth armies had surrounded Germany’s Army Group B in the Ruhr industrial valley and were in the process of reducing it.

While most of the division joined the battle of the Pocket, Wolf’s battalion was detached to the 95th Infantry Division. Wolf spent most of the campaign in a jeep. It was then that he saw his first dead body, a young German lying on the side of the road. “I remember that his hair looked dead,” he recalled.

The battalion staff soon set up a headquarters in a house. The intelligence section was at work when enemy artillery came roaring in. “It was a pretty good bombardment,” Wolf recalled. As the men charged downstairs to the cellar, Wolf almost bumped the battalion executive officer off the steps. After that scare, the battalion was soon underway again. It was during this time that Wolf found himself next to his jeep as the German artillery round exploded near him.

Wolf spent his time clearing houses for headquarters and billets, evacuating German civilians, and taking the surrender of increasing numbers of German troops. “They were most concerned that we might turn them over to the Russians,” he explained. Wolf found the Germans quite willing to rid themselves of their weapons. “I scored a P-38 pistol,” he said. The Germans were mostly docile, but the liberated Eastern European slave laborers Wolf came across were not. “They were terrorizing the civilian population.”

A few days into the campaign, Wolf was checking houses when he discovered a dead woman laid out on a bed with flowers strewn around her. “It frightened me,” he recalled. “I worried that there might be someone under the bed.” That night, he went to sleep on a wooden bench in a village pub when news came in that President Franklin D. Roosevelt had died. It was April 12. “It was an eerie day,” he said.

On April 19, the 86th joined General George S. Patton’s Third Army, as it raced through the Bavarian region of Germany. The entire division picked up speed as it plowed south. “It was mostly a romp,” said Wolf. The division used the Autobahn to advance quickly towards the city of Munich, but at the last minute, it diverted east to Freising to capture an enemy airbase. “We went through it so fast.”

Wolf now enjoyed his jeep rides. “It was a beautiful spring,” he recalled. “Lovely weather, with green grass and flowers growing everywhere.” He was riding with the battalion executive officer when they stopped at a farm and Wolf found a chicken nest filled with eggs. He pocketed as many eggs as he could. Later, he put his hand in his pocket only to realize the eggs had all broken. “That’s when I learned what a marble nest egg was,” he said. “It busted up all the other eggs.”

One day, Wolf spotted some German soldiers on a hillside. He drew his M-1 rifle, along with the soldiers around him and opened fire. “We were peppering them,” he said. “Of course, we didn’t hit anything.” Decades later, he came away impressed from the movie Saving Private Ryan and the accuracy of the American soldiers shooting Germans in the fictional town of Remel. “Every time they took a bead on a German, they hit him,” he said. “That was not our outfit.”

On May 1, Wolf’s battalion was in reserve when word reached them that General Patton would be visiting. “We polished everything but he never showed up.” Adolf Hitler’s death had more of an effect. “We learned about Hitler’s death on May 2,” he recalled. “We were all overjoyed, but by then the jig was up.”

Wolf and his battalion had penetrated about five miles into Austria, north of Salsburg, when, on May 8, 1945, the war in Europe ended. To celebrate VE-Day, Wolf and several comrades drove a jeep to Berchtesgaden, Adolf Hitler’s mountain retreat. They found Hitler’s house bombed out despite what seemed like two-foot thick walls. Books were scattered around the entrance. Upon entering, Wolf immediately recognized the huge picture window that looked out on the surrounding mountains. He had seen it before in photographs of Neville Chamberlain’s visit in 1938. “It had a spectacular view,” said Wolf. He found a book on the Russian winter campaign of 1941 and 42, filled with elaborate maps and overlays. “I took that but somehow it ended up with one of the officers.”

Wolf thought he could relax, having survived the war, but a company commander soon called out the formation and put everyone through the manual of arms. The men drilled with their rifles until the final order of pulling their triggers. Someone’s rifle fired. “Everybody but the guy who did it was laughing,” Wolf recalled. “Nobody was hurt.”

The division then transferred to Manheim, where Wolf and his team were billeted across the street from some German families. Wolf made friends with one of the families. “I never met a Nazi and never met anyone who hated a Jew,” he said. “They were all honest citizens who worked six days a week and went for a Sunday walk, not a Nazi in the bunch.”

After a week or two, the division was transferred back to Camp Old Gold. With the war still raging in the Pacific, the 86th Division would head to the United States, then across the Pacific to fight the Japanese. “We had amphibious training, so the Army wanted us there,” said Wolf.

The men boarded the SS Panama for the trip across the Atlantic. Wolf spent most of his time playing bridge. “That was a happy time,” he said. The ship arrived in New York, where Wolf visited his mother and new stepfather. She had remarried the previous October, so Wolf gained two step brothers.

All the Black Hawk soldiers were given 30-day leaves before reporting to Camp Gruber, Oklahoma. Wolf had begun training at Gruber when the atomic bomb destroyed Hiroshima. “There was much gladness,” he said. “The war is over, we’re going to be discharged.” But it was not to be. “Next thing we knew, the orders had been cut, and we’re going to the Pacific.”

As they headed to California, many of the men talked about going AWOL, but it slowly dawned on everyone that it was not an option. One man did manage to stay while the others shipped out: John DeLoren. “If there was a way of getting out of things, he did it,” Wolf said.

The men boarded a troop ship that took them to Taal, Batangas Province in southern Luzon, the Philippines. After a few days, the men were transferred to a camp near Marikina, on the outskirts of Manila. There, Wolf and his comrades guarded Japanese prisoners. “They were fat and happy,” said Wolf. “They were doing much better on American food.”

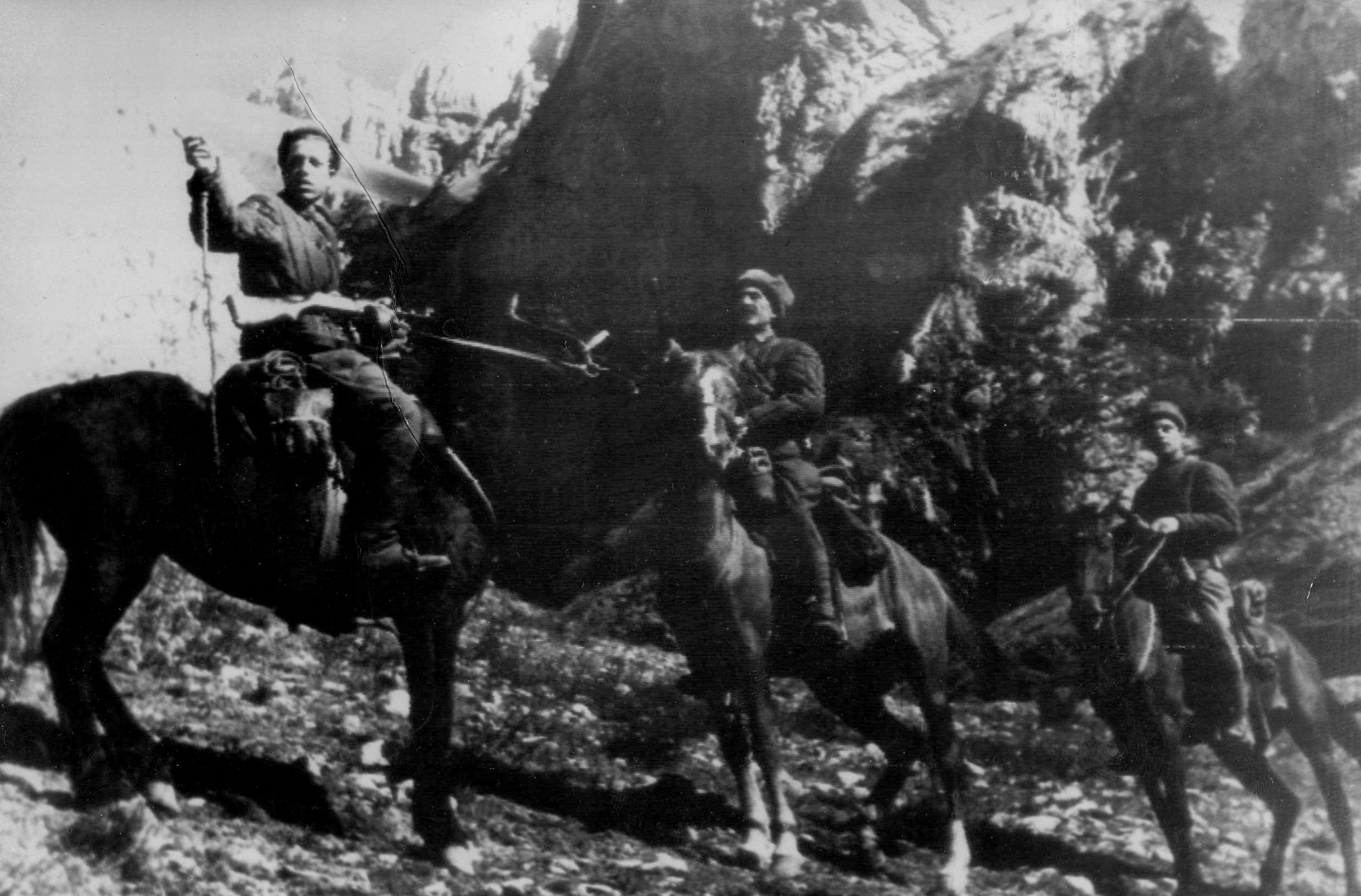

Wolf attended the war crimes trials for the Japanese generals Masaharu Homma and Tomoyuki Yamashita. He came away from the Yamashita trial thinking it was a sham. “There was so much perjury, he recalled. “Young girls would testify to all kinds of mistreatment that didn’t make sense.”

Yamashita was on trial for the atrocities committed by Japanese naval infantry in Manila in February of 1945, even though he was neither in the city, nor actually in command of the naval infantry who committed the atrocities. He had retreated to the mountains and declared Manila abandoned. The navy had disobeyed his orders. “He was tried for having failed to prevent atrocities,” Wolf said.

Both Homma and Yamashita were found guilty of war crimes and hanged. During an additional trial for a Japanese major of the Naval Infantry, Wolf departed the courtroom with his battalion commander who said, “If they are trying him for having failed to control his troops, they should have me in the next courtroom for what some of the men in my battalion did in Germany.”

As the months passed, Wolf’s rank increased until he became the battalion sergeant major. The point system to go home required 85 points (from rank, time overseas, and awards). Wolf had about 30 points at the end of war in Europe, but the point number started coming down until it reached 35. By then Wolf qualified. At the end of March, 1946, he boarded a ship headed home. “The mood on the ship was pretty happy,” he said. When he returned to the United States, he was discharged from the Army on April 24. He would later say, “I served for two years, five months, and twenty days, and when I got out I still wasn’t old enough to buy a drink.”

Returning to Yale, Wolf graduated in 1949 and went to work for an importer in New York. Later, he took a job at his uncle’s liquidating business in Miami, Florida. Still not satisfied, he drove to New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1951, and found a job with J. Aron & Co., coffee importers and sugar refiners.

While at J. Aron & Co., Wolf went on a blind date with Marie Kohlmeyer, fell in love, and married her in 1956. They had three boys: David, John, and James. Not long after their wedding, Wolf’s father-in-law asked him why he worked for a family business that he would never truly be a part of, when he could work for a family business of his own. He went to work for Kohlmeyer Company for the next 17 years.

He would later work for the Securities and Exchange Commission in Washington, D.C., and became the vice president for finance of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, He returned to New Orleans in 1983, and worked as a broker until he retired in 2000. He has been a volunteer at the National World War II Museum for the last 22 years, where he shares his war stories with interested patrons.

Looking back on the war, he admits that it taught him a lot. “I learned a lot about myself,” he said. “I learned that I could manage and I could get through it.”

Frequent contributor Kevin M. Hymel works as a historian for the U.S. Army. He is the author of Patton’s War, Volumes 1 and 2 and leads tours of General George S. Patton’s battlefields for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours. His article “Fighting a Two Front War” for this magazine is being made into the major motion picture Six Triple Eight by Tyler Perry for Netflix.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments