By Alan Davidge

That France made an early exit from hostilities at the start of World War II is well known. The speed with which Hitler’s Blitzkrieg had enveloped Denmark, Holland, Belgium, and then France in 1940 without even appearing to draw breath gave the impression that this once-great nation had neither the resources nor the appetite to take part in another European war.

The French were accused of cowardice, of being afraid to fight the Germans again after the bloodletting of the “Great War.”

This impression was reinforced by the armistice, which set up a puppet government to run the country as if it were a German vassal state, condemning its people to servitude, sending tens of thousands to concentration camps, and paying millions of francs each day in tribute to its master.

These events may have contributed to the common view today that the French simply rolled over without a fight and allowed their invaders to do their worst. In reality, however, France was still in action after the armistice had been signed and, by the end of 1944, had not only made a major contribution to its own liberation, but was fighting to end the war outside its borders, shoulder-to-shoulder with its allies.

The reasons for France’s swift collapse in the face of German pressure are easy to analyze with hindsight but came as a complete shock to its leaders and people. There was no meeting of minds between France’s essentially left-wing politicians and right-leaning generals. The military technology and strategies at their disposal belonged to the Great War, despite the fact that they had watched a progressive Germany develop its fighting power during the 1930s and learned nothing from their new tactics.

Conservatism and complacency were France’s undoing. Their concentration on developing the defenses of the Maginot Line was a clear invitation to Germany to find another short cut into France, as they had in 1914. This time the enemy chose the Ardennes, which was not as impenetrable to German tanks as the French had believed, and once again Belgium found itself facilitating the invasion of its neighbor.

For soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), sent to France for the second time in 25 years to help hold back the Germans, there was some resentment towards the French army for its apparent readiness to capitulate, but the Tommies couldn’t be expected to know the background. All they saw was what was in front of their eyes.

Fred Gilbert, an infantryman from the 51st Highland Division, surrounded and captured after Dunkirk, commented on the sight of columns of French POWs marching past: “There were thousands of them. They were carrying food, all with their full kit. They were clean and tidy. I thought to myself, ‘God, I’ve been fighting to save you bloody lot!’

“Then I looked at our boys with their torn, bloodstained battledress, unshaven and hungry, no equipment, nothing at all, all of them wounded, some of them incomplete. They had given their all to try and save France. It made me sad and, in a way, bitter.”

During the whole sorry military debacle, which led to France’s surrender, one officer stood head and shoulders above the rest. His name was Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle. A veteran of World War I, he had first-hand experience of combat and a critical appreciation of the politics involved in war. A platoon commander at the start of the Great War in 1914, he immediately saw front-line action and, by mid-1915, had been wounded twice and was awarded the Croix de Guerre for his gallantry.

In the bloodbath of Verdun the following year, where he served as a company commander at Fort Douaumont, de Gaulle was wounded twice while leading a charge against the enemy before being gassed and subsequently taken prisoner. Even then he never accepted defeat and attempted to escape five times, on one occasion dressing up as a nurse, a role not suited to his 6-foot, 5-inch frame, and which—no surprise—quickly attracted the attention of the camp guards!

As an increasingly prominent officer during the 1930s, de Gaulle developed ideas to modernize warfare, particularly in the use of tanks and the mechanization of the infantry that would facilitate faster movement on the battlefield but that did little to impress his conservative superiors. He even wrote a book on the subject which, ironically, sold more copies in Germany than in France.

By 1937 he was promoted to colonel and put in charge of a tank regiment. His self-confidence—bordering on arrogance—did not always win the approval of his peers, some of whom nicknamed him “Colonel Motors.”

When war broke out in 1939, he was placed in command of the Fifth French Army’s tanks, and within two weeks was leading an attack at Bitche at the same time as the Saar Offensive.

France’s politicians were starting to agree with his strategic ideas, but it was too late to implement them. In May 1940, two days after the German offensive began, de Gaulle was in charge of a new tank division with orders to stop the German advance after its breakthrough at Sedan.

His command was outnumbered and being attacked by Stuka dive bombers but held its ground—a task made all the more difficult because of the lack of French air support. He ignored orders to withdraw and managed to force the German infantry to retreat to Caumont, one of the very few successes against the advancing enemy.

De Gaulle’s actions earned him the opportunity to describe the attack on French radio as part of a propaganda broadcast, and on May 23, 1940, he was promoted to temporary brigadier general. Five days later he attacked the German bridgehead at Abbeville and took 400 prisoners, which helped to create an escape route for British troops falling back to Dunkirk.

On June 1 he was congratulated by the commander-in-chief of the army, Maxime Weygand, for saving France’s honor, and his new rank was made permanent. On June 5, Prime Minister Paul Reynaud gave him a government post as “Under Secretary of State for Defense and War.”

As the days passed, however, the senior ministers began to consider signing an armistice despite de Gaulle’s exhortations to fight on. Reynaud was replaced by Marshal Philippe Pétain, once the hero of Verdun but now the architect of an armistice that Pétain believed would protect the French people from further slaughter.

De Gaulle travelled back and forth to England to secure as much support as possible and address crucial issues such as the future of the French navy and possible evacuation of troops to North Africa. On June 17, 1940, he flew to London, having been relieved of his government post and in imminent danger of being arrested as the armistice was about to be signed. This he did with a heavy heart, feeling that he had turned his back on his government and his army. He was to remain in England for four years.

On June 18, de Gaulle was given permission to broadcast to the French people from the BBC in London. The previous day, France’s new president, Marshal Pétain, had told them to stop fighting in preparation for the impending armistice, which was to be signed on June 21. De Gaulle countered this by urging his countrymen to continue to fight, saying famously that they had lost the battle for France but must continue in order to win the war.

He followed this up in a similar vein on June 19 and 22, denying the legitimacy of the new French government based in Bordeaux and asking French forces in North Africa to disobey its orders. He also tried, with minimal success, to rally support from French colonies scattered across the globe.

The British government announced after the signing of the armistice on June 21 that a French National Committee—effectively a government in exile—was to be established. The armistice took effect from June 25, and on June 28 Britain announced that de Gaulle would be recognized as the leader of the Free French. The future hopes of the French people rested on his shoulders.

De Gaulle’s position was precarious over the next couple of months, and officially the “new” France, now referred to as the Vichy régime, was technically Britain’s enemy, having signed an armistice with Germany. This was to test de Gaulle’s loyalties to their limits.

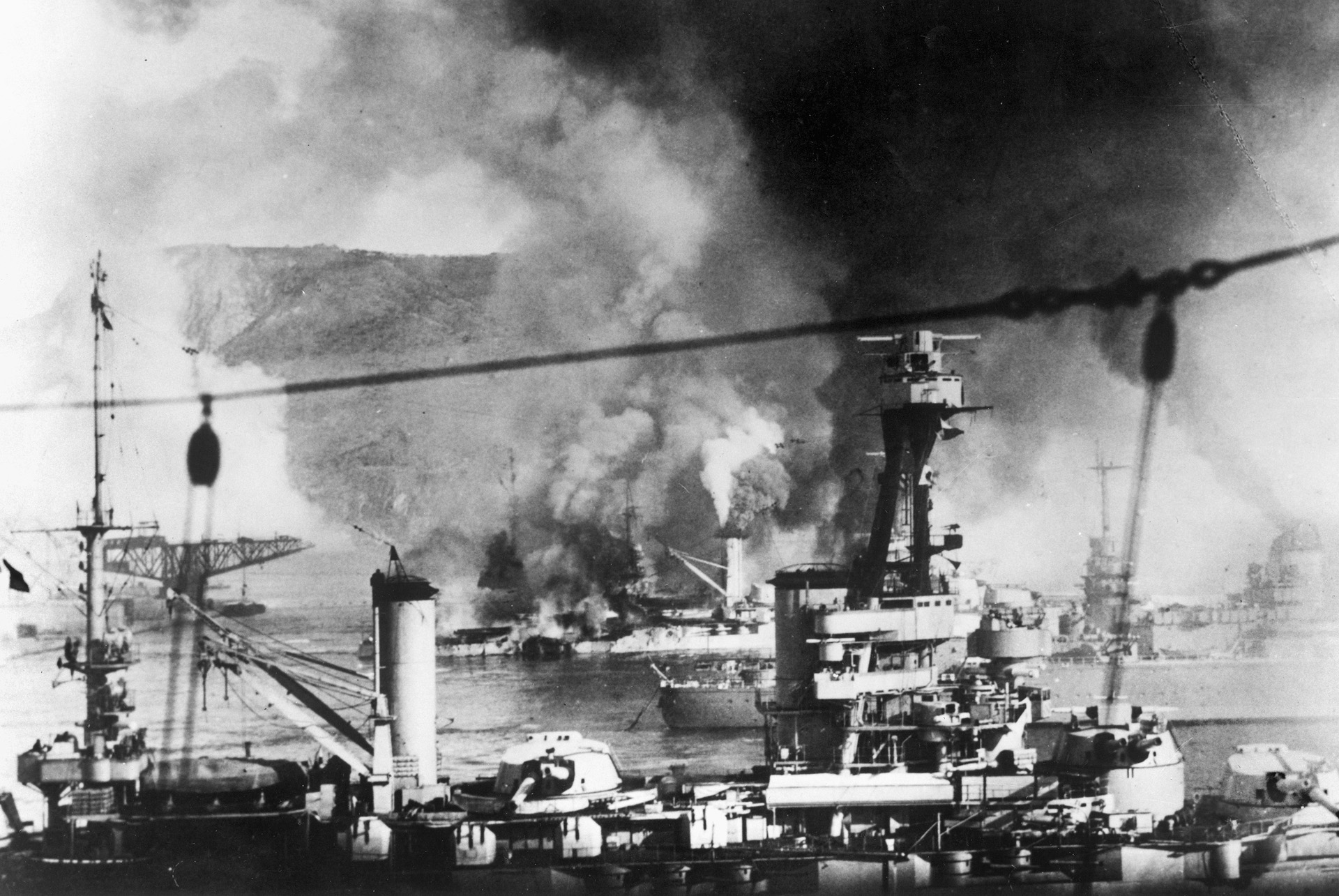

The Vichy government had laid claim to the French navy. If it then became available to the Germans, it could present a threat to Britain and the Free French, so Churchill first asked it to surrender and, when it refused, reluctantly ordered its destruction while it was moored at Mers-el-Kebir in North Africa on July 3—an attack that resulted in the deaths of over 1,200 French sailors. De Gaulle had accepted this attack publicly, and it lost him support in several quarters.

His broadcasts became more regular—around three times per month—and gave heart to communities in occupied France. Listening to them was a punishable offence, but in most towns and villages there was someone with a radio who could pass on his messages by word of mouth.

A propaganda war then began to develop between the two leaders. Vichy President Pétain’s broadcasts blamed France’s defeat on the general moral decline of the country, which suggested that everyone had some responsibility for all that had happened, whereas de Gaulle was more upbeat and precise in accounting for what had gone wrong, laying the blame squarely upon the politicians for the loss of his country.

France’s leaders may have let them down, but the country had proved, in its recent history, that when power passed to the hands of ordinary people, anything was possible.

Elsewhere in the world, some real aggression started to take place between French patriots in exile and the Axis forces. Despite the estimate that 92,000 Frenchmen were killed in the battle for France, and two million rounded up as POWs, there were significant numbers of servicemen flying the flag elsewhere.

Upon the signing of the armistice, France’s world-wide empire came under the control of the Vichy government, but some colonies very quickly demonstrated their support for the Free French side. The first of these included Cameroon, French India, French Equatorial Africa, New Caledonia, New Hebrides, French Polynesia, and Saint Pierre et Miquelon—the latter being two islands situated in the northwestern Atlantic Ocean near Newfoundland and Labrador.

The Vichy government began to lose control of other colonies, especially after Operation Torch in November 1942, when Allied forces invaded Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia; by the middle of 1943 practically the entire French empire was behind de Gaulle.

Although the majority of the French navy was out of action, there were plenty of opportunities for France’s air-force pilots to continue the war—if they could get out of the country. Over a dozen of them crossed the English Channel in time to join the RAF and take part in the Battle of Britain during the summer and early autumn of 1940.

Among them were Henri Lafont and Réné Mouchotte who, along with four colleagues, stole a Caudron Goéland from the base where they were stationed in Oran, Algeria, shortly after the armistice was signed—otherwise they would have been required to fight for Vichy France. The stolen plane had been sabotaged to prevent just this from happening, but they made it to Gibraltar and from there on to Britain via a Free French armed trawler and were welcomed as new comrades by RAF 615 Squadron. (In August 1943, Réné Mouchotte gave his life for his country while flying a British Hawker Hurricane that was escorting a group of Flying Fortresses on a daylight bombing raid on a German strongpoint near Calais. A street in Paris and an air base are named after him.)

French pilots were able to serve in other theaters of war as well. Possibly the most famous were the Normandie-Niemen airmen who fought alongside the Russians on the Eastern Front. (See WWII Quarterly, Fall 2011.)

Six months after Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, de Gaulle began to explore possible cooperation from the Free French; the outcome was the creation of the “Groupe Chasse GC3 Normandie” in September 1942, which became fully operational the following year.

Pilots trained in Russian Yakolev fighter planes and, after their first successes, became part of a propaganda campaign in Russia. Unfortunately, this marked them out for summary execution if captured by German forces.

Jean Tulasne was its original commander, and his group consisted initially of 12 pilots and 47 ground staff who were transported to Russia via Iran. As the Soviets took control of the Eastern Front, their base moved further into German territory; by the end of 1944 it was located inside Germany itself and had been responsible for shooting down 201 enemy aircraft.

They were then expanded in size, and the unit became a regiment. The Russians named them the Normandie-Niemen group after they helped capture Russia’s Niemen River (sometimes spelled Nemunas, Nioman, or Neman).

They were awarded several Russian battle honors for their efforts, which included the destruction of trains, trucks, and even E-boats, as well as shooting down enemy aircraft, plus a number of French citations and awards. On June 20, 1945, they returned home to a heroes’ welcome in Paris.

The Russian government showed its appreciation by presenting France with 37 of the Yak-3 fighter planes in which they had flown, marking the collaboration of the Free French in defending the Eastern Front and the loss of 42 of its young airmen in combat.

In colonial Africa, France faced a number of challenges, and de Gaulle selected Philippe Hauteclocque, who had been involved in the early fighting before the surrender as the commander of the 4th Infantry Regiment, to take charge in this area.

Born to a historic French family, Hauteclocque escaped France to join de Gaulle on July 25, 1940, and was promptly given the rank of major and sent to Africa as governor of French Cameroon. To avoid possible reprisals that would put his family in danger, he subsequently took on the name “Leclerc.”

Leclerc consolidated the Free French position in central Africa and led a successful attack on Gabon, relieving it of its link to Vichy. He was next sent to Chad, whose border with Italian-held Libya made it vulnerable; he and his forces systematically destroyed several Italian bases in the desert.

The following year, under de Gaulle’s instructions and now promoted to general, Leclerc invaded Libya and drove his troops as far as Tripoli. At this point the Free French forces were fused with Giraud’s Army of Africa to form the French Expeditionary Corps.

The Army of Africa was a colorful outfit with a historic reputation. It consisted of zouaves, tirailleurs, and infantrymen from Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia, plus the fabled French Foreign Legion. They had been sent to France at the outbreak of war but, after the armistice was signed, their numbers were limited to 120,000 men.

General Maxime Leygand, who preceded Giraud, was however able to train a further 60,000 under various guises such as auxiliary police. The combined armies subsequently supported the British Eighth Army under Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery in its invasion of Tunisia.

By the time the Germans and Italians had been defeated in North Africa, Leclerc had established a major role and reputation for the French among the allies, and his unit of over 4,000 men became the 2e Division Blindée (2nd Armored Division), equipped by the Americans with new Sherman tanks and other weaponry. It was soon to have a significant role in the liberation of France.

While members of the French army in exile were playing an active role in fighting the Axis powers, there were signs that ordinary people at home were beginning to take control of their own destiny.

On the night of Easter Sunday 1941, a British Wellington bomber returning from a successful raid on an airfield near Bordeaux crashed into the center of the small town of St. Sever-Calvados in German-occupied Normandy, killing all the crew on board and nine civilians.

A Sergeant Rawlings, a gunner on board the plane, had previously bailed out with a Verey pistol to signal a spot for a safe landing, but a wing tip of the Wellington clipped a chimney on its approach, and it crashed in flames.

When Rawlings was picked up by the Germans, they paraded him through the streets, identifying him as responsible for the deaths of those innocent French civilians who had perished in the crash. This vindictive act gained no response from the townspeople and was to backfire spectacularly over the next few days.

Neighboring towns were quickly made aware of the tragedy, and when the British airmen were interred a few days later, a crowd of nearly 4,000 people came to pay their respects, some cycling many kilometers to join the mourners who packed the streets.

As the population of St. Sever was no more than 1,400, this was clearly a gesture of defiance and a sign of things to come. Word spread quickly among the forces occupying Normandy, and it was decreed that anyone attending the burial of allied soldiers in the future would be punished.

The message from this small French town was clear: they may have suffered a humiliating defeat and enforced occupation, but they would demonstrate their solidarity and resistance until the opportunity to get their country back presented itself.

For any public resistance to be effective, it would ultimately require coordination, and de Gaulle’s speech on June 18, 1940, urging civilians not to comply with the forces of occupation, provided an initial starting point.

France also had at its disposal disparate groups that had escaped persecution elsewhere—some with experience of guerrilla fighting, such as those who had fought in the Spanish Civil War, and also Poles, German, and Italian anti-fascists and Jews from other parts of Europe. Initially, however, most of the resistance was passive and concentrated on locally printed propaganda.

By 1942 it was estimated that around 300,000 copies of leaflets were being read by two million people. These carried advice on how to make life difficult for the Germans and provided motivational stories of German defeats elsewhere.

The previous year saw the first signs of the unification of resistance groups, with Jean Moulin, the prefect of Eure-et-Loir, southeast of Normandy, as a key figure. He used his network of contacts to pull groups together and liaise with de Gaulle and the Free French. Coded messages from the BBC broadcasts provided a major source of communication.

As informal resistance groups developed into the French Résistance, which the Germans saw as a real threat, their members discovered the level of risk involved: Jean Moulin was arrested and tortured, and he died in captivity in 1943.

Many more were to suffer a similar fate for their country. A glance at the war memorials constructed in French towns from 1919 onwards often reveals names of civilians from the 1939-45 war who made the supreme sacrifice to help win the war.

In order to distinguish between the Free French and the Résistance, de Gaulle began referring to the latter as the French Forces of the Interior (FFI). The use of a generic title should not, however, create the impression that they were a unified group.

Not only were resistance groups disparate in nature, but they were also diverse in their final aims; and some, like the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans (FTP), were connected with the Communist Party and wanted a different political outcome for France. This was to present difficulties for de Gaulle and the Free French when liberation actually occurred.

In addition to the urban resistance fighters, there were guerrilla groups called Maquis, based in the countryside. Some of these were men who had taken to the hills to escape conscription into the Vichy forces. They were particularly active in the Alps, Brittany, and Limousin, a region in southwest-central France. A significant number also belonged to communist groups. They were frequently well-armed and worked closely with the Special Operations Executive (SOE) of Britain. Many played a significant role in helping downed Allied airmen to escape.

As well as communication and propaganda, the main activities of the Résistance included intelligence gathering, sabotage, and actual guerrilla warfare.

In the early part of the war, intelligence was of paramount importance. De Gaulle set up a French intelligence network in London (the BCRA), which worked closely with British intelligence and the Résistance. Information was sent and collected by radio operators (pianistes) and later by Westland Lysander airplanes, specially designed for low flying, short take-offs and landings, and dropping canisters full of information or supplies.

Good information meant more weapons and supplies for the Résistance, so there was a big incentive to perform well. Intelligence gathering by the French greatly assisted their liberation on D-Day as the Allies became much better informed and kept up to date about the German defenses and troop dispositions.

Sabotage often included damage to railway lines, such as unbolting connector plates to derail supply trains, the use of explosives to destroy tracks and bridges, or simply the undetectable mistakes made by forced-labor groups on equipment being made for the enemy.

The French who organized their own explosive production ran great risks. A renowned French female chemist by the name of France Bloch-Serazin, who was making explosives in her Paris apartment, was arrested in February 1942, tortured, and taken to Hamburg to be guillotined as a result of her activities.

More often, however, explosives were stolen from the Germans. Where sabotage was possible against strategic targets, it could be more effective than bombing raids and saved Allied resources and airmen’s lives, but the risks that the saboteurs took were considerable.

Guerrilla warfare was also a particularly risky business, and not just for the perpetrators. It was practiced largely by the communist groups initially, but the assassination of a German officer on the French Metro in 1941, which was avenged so brutally on innocent civilians, provided a disincentive to French resistance groups, although they were increasingly becoming well armed. Their time, however, came after D-Day, particularly during the liberation of Paris, when they could operate in the open and put their training and weapons to good use.

While the Résistance was doing its best to subvert the German occupation, French forces outside of their homeland were doing their utmost to make the liberation happen as soon as possible. In addition to the regular soldiers who secured North Africa, other French troops were being selected for specialist and skilled duties elsewhere. One airborne group that was formed in 1940 joined the British Lt. Col. David Stirling, and the following year became the 1st French SAS Regiment.

In addition to these, a series of commando groups were created by de Gaulle and trained alongside the British Chindits and fought in French Indo-China to liberate it from the Japanese, who had occupied it since 1940. They became part of the Far East French Expeditionary Force.

During the Italian campaign in 1943, the French Expeditionary Corps under General Alphonse Juin was given a major combat role. By May 1944, the FEC found themselves facing the daunting defenses of the Gustav Line and the heights of Monte Cassino which, since autumn 1943, had been devouring the finest American, British, and Commonwealth troops seeking a breakthrough that would lead to Rome and eventually Germany itself.

Their performance in tackling the Gustav Line was exemplary. The 1st French Division, with comrades from Morocco and Algeria, outflanked the German defenses and won huge praise from Fifth U.S. Army commander Lt. Gen. Mark Clark: “In spite of the stiffening enemy resistance, the 2nd Moroccan Division penetrated the Gustav Line in less than two days’ fighting.

“The next 48 hours on the French front were decisive. The knife-wielding Goumiers swarmed over the hill, particularly at night and General Juin’s entire force showed an aggressiveness hour after hour that the Germans could not withstand.

“Cerasola, San Giorgio, Mount D’Oro, Ausonia, and Esperia were seized in one of the most brilliant and daring advances of the war in Italy. For this performance, which was to be a key to the success of the entire drive on Rome, I shall always be a grateful admirer of General Juin and his magnificent FEC.”

By this time, the tide was turning against Germany. Italy was already out of the war, and the plans for the invasion of Europe were almost complete. The French army in exile would soon be coming home. In a short while, French troops would join the D-Day liberators, squeeze the Germans out of Normandy, then land in the south of France and penetrate to the north. Paris would be the next prize, and France would belong to the French once more.

However, the social and personal divisions created during the occupation and the desire of some of the Résistance units to swing hard left politically would mean further challenges were in store for a liberated France.

The announcement of Operation Overlord (D-Day, June 6, 1944) to the French people was undertaken by the Résistance through a clever plan hatched with the Special Operations Executive (SOE) through the BBC.

When the first three lines of a poem by Jean Verlaine, Chanson d’Automne (Autumn Song) were broadcast, it meant that the landings were imminent; it was agreed that the broadcasting of the next lines would signify that the landings would take place within 48 hours, so that the French support-and-sabotage plans could be put into action.

The first lines were broadcast on June 1 and the next lines on June 5. The French population was going to do everything possible to facilitate the arrival and progress of Allied troops. This was the beginning of the liberation of Europe, and a successful removal of the enemy from France would provide the necessary initial impetus to carry them all the way to Berlin.

Although the D-Day landings were undertaken mostly by British, American, and Canadian troops, the day was also a homecoming for Commandant Philippe Kieffer’s commandos—177 in total—who were attached to Lord Lovat’s 1st Special Service Brigade, which landed at Sword Beach.

Eyewitness accounts suggest that Lovat’s lead boat pulled back to allow the French commandos to touch down first on the sand. One can only imagine how it felt for them and for the local population to see troops in French uniforms for the first time in four years. Their prayers had been answered!

Elsewhere in northern France, other French servicemen were taking part in the liberation. Thirty-two paratroopers were dropped in Brittany overnight and five Free French squadrons (three fighter and two bomber) were supporting the beach landings.

Despite the disaster at Mers-el-Kebir, Algeria, when the Vichy-aligned French fleet was decimated by the British Royal Navy in July 1940, the Free French had a small navy, mostly provided by Britain, and there were Free French sailors serving on some British ships.

Along the Channel coast between Omaha and Gold Beaches, the cruisers Montcalm and Georges Leygues were pounding the enemy’s beach defenses. In front of Omaha Beach, the destroyer Roselys moved closer to the shoreline to provide supportive fire, with another destroyer, La Combattante, doing the same at Juno Beach.

The Résistance had played an important role in providing updated intelligence for D-Day, and many groups were now able to directly help their liberators by disrupting communications that were crucial to the German response. But in doing so, many were exposing themselves to an enemy that was becoming increasingly vindictive.

Everyone had to be more careful, especially in towns and villages some distance from the coast, which could not expect to be liberated for weeks. In Beaucoudray, south of St. Lô, a series of errors among members of the local cell of postal workers engaged in a sabotage plan resulted in 11 being caught and shot on June 15. Similar tragedies were to occur elsewhere before the liberators could arrive in sufficient numbers to take charge.

De Gaulle returned to France on June 14, transported by the destroyer La Combattante, and landed on Juno Beach, a spot commemorated today by an enormous steel Cross of Lorraine. He went straight to Bayeux to make a speech to a crowd of 2,000 and began describing the new political structure he envisaged for France.

Thanks to Eisenhower’s support and the dynamic efforts of the Free French, the country had escaped being put under AMGOT (Allied Military Government for Overseas Territories), which was what eventually happened to Germany, Italy, and Japan. De Gaulle subsequently visited Isigny-sur-Mer, between Utah and Omaha Beaches, inspecting progress on the other beaches and raising morale among the locals.

On August 1, General Leclerc arrived from North Africa at Les Dunes near Utah Beach with his 2nd Armored Division, comprising 16,000 troops, 3,000 vehicles, and 250 tanks. This event is commemorated by an open-air display, popular with French visitors and regarded as the place where La Libération began in earnest.

His division was part of Maj. Gen. Wade Haislip’s XV Corps belonging to Lt. Gen. George Patton’s Third Army. The division swung into action immediately as part of Operation Cobra, the breakout from the beachhead.

The 2nd Armored Division continued to play a major role alongside American and Canadian forces over the next two weeks in pushing the German army towards Argentan at the southern end of the Falaise Pocket, practically destroying the 9th Panzer Division in the process. The Germans lost 4,500 troops killed and 8,800 taken prisoner, as well as an enormous destruction of vehicles, including 117 tanks.

Leclerc’s passage through French towns and villages along the way was triumphant. Not only was France being liberated, but the act was being performed by Frenchmen.

What happened next crowned Leclerc’s career and helped to shape the future of France. Originally, the plan had been to bypass Paris and keep chasing the enemy back to the Rhine, but on August 19, the Résistance in Paris started to take the law into its own hands.

The situation had been coming to a head since August 15, with strikes by police and key workers and a general strike planned for August 17. Colonel Henri Rol-Tanguy, the communist leader of the Résistance (FFI), decided that, as the German position was weakening and the Allies were on their way, the time had come for the uprising that they had been planning for months.

When the news reached Leclerc, who had just fought his way to a position where he could help to complete the planned encirclement of the German army just east of Falaise and Argentan, it placed the Free French on the horns of a dilemma.

Memories of the recent brutal crushing of the uprising in Warsaw by the Germans were too powerful to allow the FFI to take on the Germans in Paris on their own. De Gaulle felt the same and urged Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower to liberate Paris as soon as possible.

Originally, the liberation of Paris was not high on the Allies’ priority list. The Americans and British did not want to get bogged down in the nightmare of an urban-combat scenario, nor be responsible for feeding millions of starving Parisians. But humanitarian concerns and the value of the boost to Allied morale if Paris were liberated outweighed the negatives.

Ultimately convinced, Eisenhower decided to leave a small contingent from the French 2nd Armored Division near Argentan to help the Americans close the Falaise Pocket on the retreating Germans. Leclerc, with the bulk of his troops, and the U.S. 4th Infantry Division were sent at full speed towards Paris to liberate the city and avert the slaughter of the FFI and civilians.

Leclerc reached the outskirts of Paris on the night of August 24, followed by the rest of his division and the Americans, who arrived the next day. This was not a moment too soon, for Hitler had issued orders for anything of value to be destroyed; dynamite charges had already been attached to bridges and public buildings.

Dietrich von Choltitz, the German commander left in charge of the city, was disinclined to see the treasures of Paris reduced to rubble and was ready to accept that his war was over. He agreed to surrender and declare Paris an “open city.”

René Champion, a French-American soldier in Leclerc’s division, was driving one of the first tanks—a Sherman named Mort-Homme (Dead Man)—to enter Paris. He recalled, “As we rode through the city streets, heads high, hearts swollen with pride, eyes shining, black berets at a jaunty angle, I almost had the feeling that the war had come to an end and that I was taking part in a victory parade.”

As the platoon of tanks rolled single-file toward its objective—the Hôtel Maurice, the German headquarters—they suddenly came under enemy fire. “I heard the voice of my tank commander in my earphones: ‘Faster, Champion, faster!’ A moment later the tank was rocked by a tremendous explosion and it began to fill with thick billows of acrid smoke. I knew immediately that we had been hit….

“Stunned by the explosion, I let the tank roll forward for a few moments before I realized that it was on fire and that all the ammunition in it would explode at any second.” Halting the tank, Champion scrambled out of the machine, then ran back and grabbed a fire extinguisher to put out the flames. Two of the crewmen, hurt but alive, had crawled out of the bottom escape hatch.

Despite sniper fire, Champion managed to run two blocks back to where an infantry unit was waiting to move forward and found someone with a stretcher. They ran back to the tank to care for the wounded.

The tank platoon’s mission was successful, Champion said, “But it had also been costly. In my platoon alone, four of our five tanks had been hit by grenades and anti-tank missiles. Two of our tank commanders had been killed. More than a dozen others, out of 25 men, had been injured. Among them were my own crew commander and my gunner, as well as Jacques Diot, the loader.”

That evening, after the battle of Paris was over, an exhausted Champion lay on the ground in the Jardin des Tuileries and tried to sleep, but all he could do was think about the day: “Beautiful, wonderful Paris! How we had cherished the dream that we might someday be the ones to liberate it…. The dream had become truth and the truth had been far more thrilling and deeply satisfying than I had ever imagined.”

A victory parade through the streets of Paris on the 25th was cheered by hundreds of thousands of Parisians. De Gaulle led the parade, walking proudly down the Champs Elysées as he was showered with cheers and flowers. Even the occasional sniper’s bullet failed to cause him to panic. He was shot at later that day in the middle of Notre-Dame Cathedral during a prayer of thanks but again refused to flinch.

As the President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic, de Gaulle made a rousing speech at the Hôtel de Ville (city hall) to the French people, praising the role of the Résistance and the Free French army in seizing the capital but urging against complacency. The enemy was still on their soil, and France now needed a new government of national unity, reflecting the contributions all had made toward their liberation.

He was particularly concerned about bringing together the strong communist element that had driven much of the resistance internally with all other groups. He pointed out the duty France now had to help liberate Belgium and Holland as well as defeat Germany.

There was at last an opportunity to take a little time out for victory celebrations in spite of the food shortages being suffered by Parisians. Thanks to a huge effort by the Allies, supplies poured into Paris, and within 10 days the capital was ready to continue assisting with the liberation of the rest of France.

From August 15, southern and central France had been witnessing the country’s “Second D-Day” as American, British, and French troops participating in Operation Dragoon drove up the Rhône Valley after having landed in Provence and secured the ports of Toulon and Marseille.

The key driving force was Army B, led by Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, a veteran of 1914-18, who joined de Gaulle in 1943. His army was composed of elements of Free French, the Army of Africa, and volunteers, and made up seven divisions which, when amalgamated with three U.S. divisions, Special Forces, and Airborne Forces, comprised Lt. Gen. Alexander Patch’s Seventh U.S. Army.

De Tassigny was then joined by former FFI fighters, giving him a strength of 400,000 men. At the end of September, Army B was redesignated the First French Army.

Operation Dragoon had been a great success, achieving its main objectives in four weeks. The Germans rallied in the Vosges mountains near the border with their homeland, but they were no match for the American Seventh and French First Armies, which, by then, had been joined by Leclerc’s 2nd Armored Division.

On the way there, Leclerc had liberated Lorraine and practically destroyed the German 112th Panzer Brigade. He renewed contact with his comrades in Haislip’s XV Corps and then drove into Alsace, liberating Strasbourg on November 23 and receiving a Presidential Unit Citation for the actions of his division.

De Tassigny remained in the Vosges area as part of General Jacob Devers’ Sixth Army during the time when the Battle of the Bulge, effectively Hitler’s last stand, was taking place further north in the Ardennes.

This costly engagement, although involving mostly U.S., British, and Canadian forces, also saw a valuable contribution from the French. Two light-infantry battalions were attached to Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins’ VII Corps, and a further six were attached to Troy Middleton’s VIII Corps.

Further support came from France’s 3rd SAS 1st Airborne Marine Infantry Regiment. The efforts of the Wehrmacht during the Battle of the Bulge checked the Allied advance, and it looked as if the recent gains in Alsace such as at Strasbourg, between the Vosges mountains and the German border, would have to be abandoned. But de Tassigny held on, despite heavy casualties around Strasbourg itself.

German counterattacks during their Operation North Wind in the area around Colmar, south of Strasbourg, led to four divisions from Maj. Gen. Frank Milburn’s U.S. XXI Corps being placed under de Tassigny’s command as reinforcements—the only time that a French general commanded a U.S. unit in World War II. Colmar was liberated three weeks later.

The capture of Strasbourg, on the German border, was of great personal significance to Leclerc and his men. On March 1, 1941, after the capture of Kufra in Libya, his first major battle in North Africa, he and his men swore an oath that has gained a page in history as “The Oath of Kufra:” “Not to lay down arms till our colors, our beautiful colors, fly over Strasbourg Cathedral.”

Elsewhere in Europe, beyond its own frontiers, France was assisting in the liberation of the Benelux countries. As part of Operation Amherst, April 7-8, 1945, 700 troops from the 3rd and 4th French SAS were dropped in the Netherlands as part of a nighttime mission to spearhead the attack on key facilities held by the Germans and hold onto them until relieved by Canadian forces.

Fighting in Alsace continued into March 1945, and the 2nd Armored was then sent to Royan on the Atlantic coast, where it forced a major German surrender on April 18. On April 21, the rest of de Tassigny’s French First Army took the industrial city of Stuttgart.

The French 2nd Armored Division returned to the east in pursuit of what was left of German Army Group G into Swabia and Bavaria, arriving at Berchtesgaden—known as Hitler’s “Eagle’s Nest” mountain retreat—during the first week of May, just as the Germans were preparing to surrender.

Sergeant Joe Guennel, a member of an American POW-interrogation team, had also made it to Berchtesgaden before any of the other U.S. units arrived. He recalled, “We woke up on a beautiful Sunday morning, but the tranquility was shattered by roaring engines. The French 2nd Armored Division tankers were in town, racing up and down the main thoroughfare of Berchtesgaden in the black Mercedes limousines that they had liberated from their garages on the Obersalzburg. I recall hearing that Generals Leclerc, de Tassigny, and de Gaulle each received one of those symbols of victory.”

In the last few days of the war, both at home and in lands to the east of its borders, France was giving as good an account of itself as any of the Allies that had been fighting the Axis powers during the last five-and-a-half years.

It had its new war heroes, a charismatic leader who had never given up on his promises, despite being forced out of his country, and its people had finally shrugged off those who had invaded and brutally occupied their homeland since 1940.

The French had displayed exceptional courage and had taken great personal risk to get their country back. Of course, servicemen from Britain and North America and other allied countries also gave their all, but their circumstances were a little more predictable.

They enlisted, built up a camaraderie among their mates, were comforted that there were support mechanisms for their families at home who, in turn, were supplying them with their own forms of support, whether it be letters from loved ones, or stirring words from Winston Churchill, or songs from Vera Lynn and Glen Miller on the radio.

They were driven by the dream of coming home to a hero’s welcome and the chance to continue where they left off with their families.

In contrast, the French Résistants knew that, if caught, their families could be punished as well as themselves and, of course, they didn’t know which of their neighbors were actually informants or collaborators.

The Free French soldiers fighting overseas were very much on their own and could not be sure whether they would be going home as prisoners to an occupied country or, as it happened, fortunately, to a free France.

Their leaders were exceptional, however, and were real role models. De Gaulle, Leclerc, and de Tassigny in particular—who, in two world wars, must have stopped enough enemy rounds between them to fill a rifle magazine—were men who faced danger every day (for de Gaulle it was the ever-present possibility of assassination), and they were an inspiration to their men.

Despite all this, France was now set to undergo a challenging and confusing post-war period in its history that saw public (and private) trials and executions of those who were deemed responsible for the misery that the country had suffered.

Women who had consorted with the enemy had their heads shaved and were paraded through Parisian streets in their underwear to face the scorn of the population. Vichy leaders were rounded up and sentenced; collaborators became, at the very least, social outcasts; and many ended up as the victims of some very rough justice as old scores were settled.

France had, however, seized victory from the ashes of defeat and humiliation, and de Gaulle’s prediction in June 1940 that, although it had lost the battle for France, it would win the war, had come true. This had been achieved by a well-organized and largely invisible Résistance network at home and an army in exile, still fighting for its country around the world.

This army, which not only returned home with its allies to liberate its homeland in 1944, but then made up for lost time by joining the war effort in Europe, contributed significantly to the victory over Nazi Germany the following year.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments