By David H. Lippman

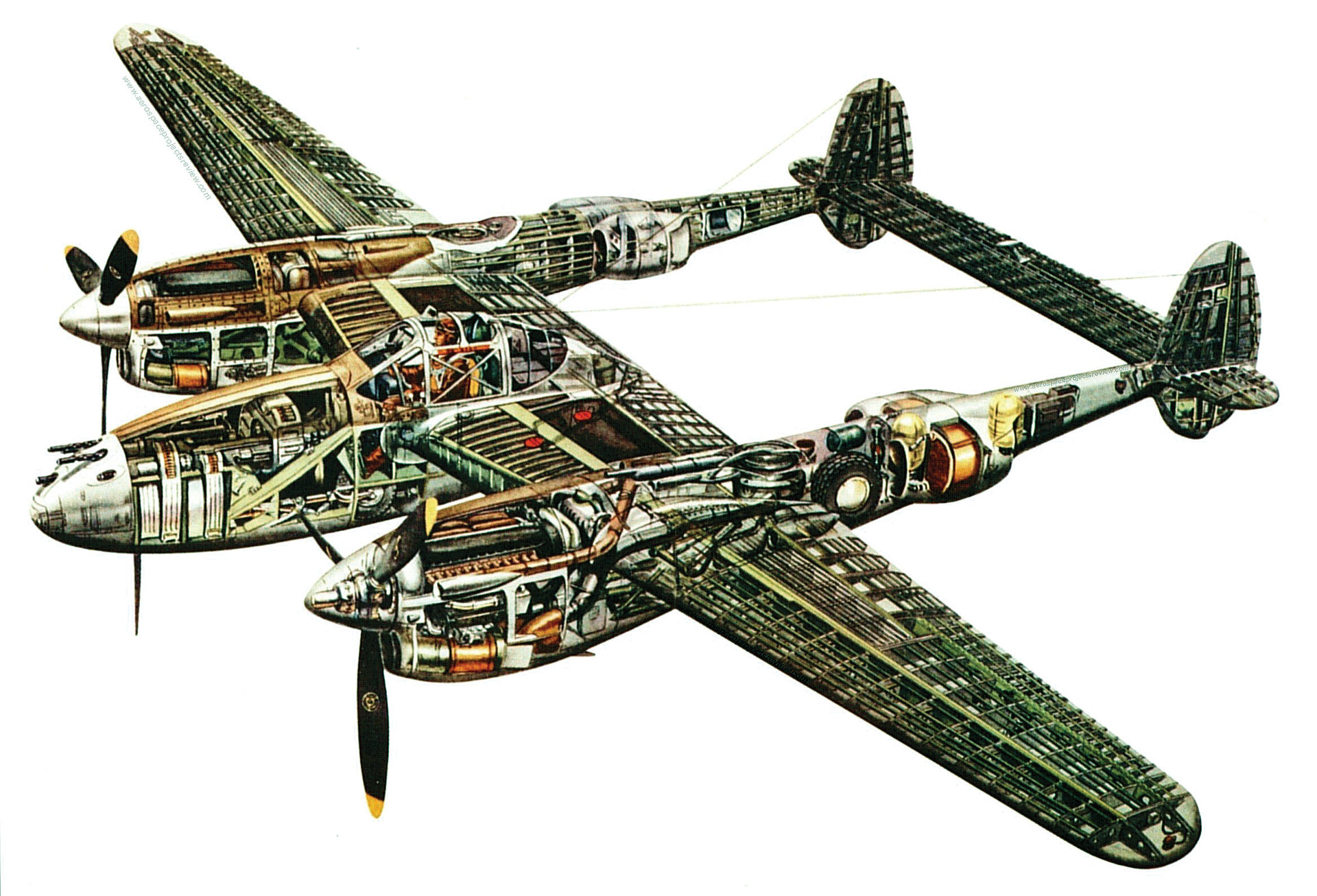

Technically and visibly, it was unique among World War II fighters. The P-38 stood on tricycle landing gear, with its twin Allison engines in separate booms and the pilot sitting in his cockpit in a cupola between the booms. It was an ungainly appearance, compared with sleek British Spitfires and American P-51 Mustangs.

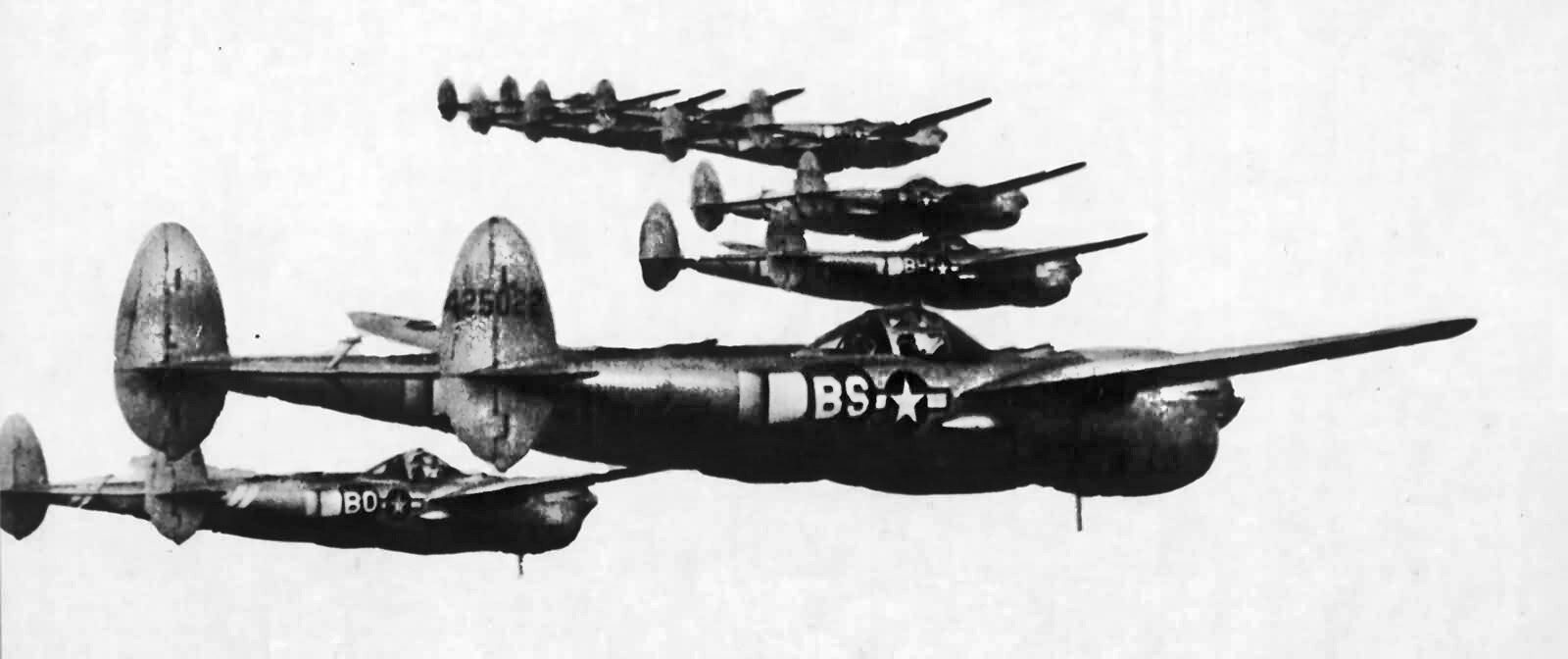

But the P-38 was one of the greatest fighter-bombers of the war, dominating the skies of the Pacific and Europe in many roles—top-cover fighter, bomber escort, tactical bomber, and most notably, the weapon that brought down Japan’s greatest warrior.

In January 1937, the U.S. Army Air Corps sought proposals from aircraft manufacturers for a new interceptor that could attack “hostile aircraft at high altitude.” It required a maximum speed of 360 mph at 20,000 feet and a maximum level speed of 290 mph at sea level. It needed to fly at full power for one hour at 20,000 feet, and have a six-minute rate of climb to that altitude. In addition, the fighter required a takeoff-and-landing distance of 2,200 feet while clearing a 50-foot obstacle at runway’s end. The Air Corps also wanted an in-line engine, comparable with Britain’s new Hawker Hurricane and the Luftwaffe’s Messerschmidt Bf-109. All of this was deemed possible in the days before effective radar.

Among the companies that responded was Lockheed, based in Burbank. Starting with doodles and finishing at drafting tables, they developed a twin-engine design, realizing that the Air Corps’ demands could not be achieved with a single-engine plane. But a pair of the new Allison V-1710-cubic-inch-capacity engines on a single wing-and-tail frame could generate the necessary 1,000 horsepower needed.

Eventually they came up with a winner. The pilot would sit in a centerline cupola between twin booms that ran from engines to tail, connected by the rudder. The design proved to be stable in flight and as a platform for its 20mm cannon and four .50-caliber machine guns, all nose-mounted. In its bomber role, it could lug one 2,000-pound bomb, two 1,100-pound bombs, two 500-pound bombs, or 10 half-inch (127mm) rockets.

In all, the P-38 as delivered in its varieties turned out to meet the Air Corps’ standards — its top speed was 414 mph, top altitude was 25,000 feet, and it boasted an impressive range of 585 miles.

The P-38 had a wingspan of 52 feet, stood 9 feet, 10 inches tall, and was 37 feet, 10 inches long from nose to tail.

Ironically, its military career would start off with disaster. Air Corps Project Manager Lieutenant Ben S. Kelsey made tests flights with the prototype XP-38 over the California desert without mishap and then took off from Los Angeles on February 11, 1939, headed for Mitchel Field on Long Island, amid the usual publicity given to major distance flights. With two stops for fuel, he covered the 2,400 miles in seven hours. But as he landed at Mitchel Field, Kelsey came in too low. The plane crashed into a ditch and then a golf club, becoming a total wreck, but leaving Kelsey unscathed.

Despite this ending, the transcontinental flight had been a major success. It had displayed everything Lockheed promised for the fighter, and everyone there went back to their drafting tables to iron out the flaws for the next test version, the YP-38. The YP-38 flew up to advertised standards, with Air Corps brass calling it “a new kind of cat.”

Washington then ordered 686 P-38s, whose name was to be the “Atlanta.” However, some were to be exported to the British, who disliked naming a tough fighter after an American city. They proposed to call the new machine the “Lightning.” The Americans agreed, and that was the name that stuck.

The early trial model P-38s still had trouble with the unusual tail unit, which was buffeted heavily in maneuvers. Lockheed designers went back to the drawing boards, adjusting the tail plane and changing the elevator mass balancing, and the first operational P-38Ds were delivered to the Air Corps in March 1941.

The P-38Ds were soon followed by P-38Es, which mounted a 37mm nose cannon instead of the 20mm and new electric and hydraulic systems. Lockheed also built 99 P-38Es as F-4 reconnaissance planes, which replaced the nose armament with a cluster of four cameras. These proved highly successful in all theaters, as did their successor, the F-5.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, P-38s were deployed overseas. F-4 versions were assigned to Australia to conduct snooper missions over Japanese positions in New Guinea. One F-4 was jumped by six Japanese Zeros. Unable to shoot back, the F-4 suffered heavy damage, and one engine was knocked out. The unfazed pilot yanked his surviving engine into a climb that pulled him away from the Japanese.

The first kill for any American plane in Europe took place on August 14, 1942, when Lieutenant Elza Shahan of the 27th Fighter Squadron was patrolling in his P-38 over the rugged volcanic terrain of Iceland. Shahan spotted a P-39 Airacobra flown by Lieutenant Joseph Shaffer of the 33rd Squadron, battling a four-engine Luftwaffe Focke-Wulf 200 Condor.

Shaffer fired cannon shells at the Condor, setting it aflame, but not shooting it down. Shahan, taking advantage of his P-38D’s diving ability, swooped in and fired a long burst into the FW-200, and it exploded for a confirmed kill.

The invasion of French North Africa in November 1942, and the following Tunisian campaign called for the P-38’s long range and resilience. P-38s were assigned to North Africa in great numbers, including to the legendary 94th Squadron, Eddie Rickenbacker’s “Hat in the Ring” outfit of World War I.

The P-38s got down to business on November 21 at Youks-les-Bains, a base where pilots and crews suffered from shortages of food and water. Two strafing attacks on German mechanized columns did plenty of damage, but six returning P-38s crashed in the dark.

P-38s flew interdiction and ground-attack missions against German and Italian forces with increasing success. Their performances impressed enemy and friend alike. Luftwaffe fighter ace Hans Pilcher (75 kills) wrote that when he tried to make a tail attack on a P-38, it “disappeared, leaving us with our mouths wide open.”

When Lockheed’s new P-38Fs and P-38Gs arrived in North Africa, they were assigned to a new role—blasting German cargo planes, motorized units, and convoys on the high seas. The new P-38G was well-equipped for this role: It had larger racks to accommodate bombs or fuel tanks, improved turbochargers, and a better oxygen system.

On January 21, 1943, two squadrons of P-38s hammered Axis road convoys, destroying 65 vehicles and killing hundreds of Axis soldiers. The Lightnings went down on the deck, and one pilot crashed into a telephone pole, cutting it in two. He managed to make it home safely. In late February, the Germans tried reinforcing Tunisia by air, and P-38s swooped in on hundreds of Junkers Ju-52 transports, sending the tri-motor planes crashing into the sea.

Despite these successes, the P-38s received sometimes-mixed reviews from German fighter aces. Colonel Johannes “Macki” Steinhoff, based in Sicily, met them in his Bf-109 and said his plane could fly faster than the Lightning, but a P-38 could turn tighter and get on his tail faster. But he regarded his squadron mates’ reports that the P-38 had more powerful guns as exaggerations.

However, the question became moot when the Allies conquered North Africa. P-38 squadrons moved to England to escort American heavy bombers to targets in Germany.

By now newer versions of the Lightning were arriving in English bases: the P-38F, P-38H, P-38J, and P-38L, which had tail-warning radar. They were sorely needed. On October 14, 1943, the USAAF lost 60 B-17s in an ill-fated and unescorted raid over Schweinfurt, Germany. The next day, 55th Squadron of P-38s was declared operational. They flew an escort mission to Bremen on November 3 and lost seven planes. More trouble ensued after that. Miserable European weather put pilots in heavy coats and inflicted damage on engines. Cockpits were bitterly cold. Pilots could not use controls because of frostbitten hands and feet. Freezing temperatures affected the Allison engines and made them maintenance nightmares.

Worse, the theory behind the P-38 was not working. The intense cold made P-38Hs useless at high altitudes, but more than a match for Bf-109Gs—Germany’s top model—below 18,000 feet. In the summer of 1944, the 55th Squadron converted to P-51s, improving both their kill rate and morale.

In January 1944, during the run-up to the Normandy invasion, the Ninth Air Force decided to assign its P-38s and P-47s to the fighter-bomber role so that they could take advantage of their range and bombload factors to blast German troops, convoys, airfields, and installations. General Jimmy Doolittle, who commanded the Ninth, used a P-38 as his personal plane on the correct theory that nobody would mistake it for a German aircraft.

But the Lightnings still found opportunities to smash the Luftwaffe in the sky, as 20th Group shot down 10 Luftwaffe fighters for the loss of two P-38s, a 376th Squadron pilot became an ace in one day on August 25, and in another single day P-38s accounted for 21 Luftwaffe fighters for the loss of one American.

In the Mediterranean, P-38s showed their value as Allied forces drove up the Italian “boot” from Sicily as both fighter escorts and fighter-bombers. On August 25, 1943, 140 P-38s hammered the Foggia airfield complex in Calabria, blasting open hangars, rail yards, trucks, and trains.

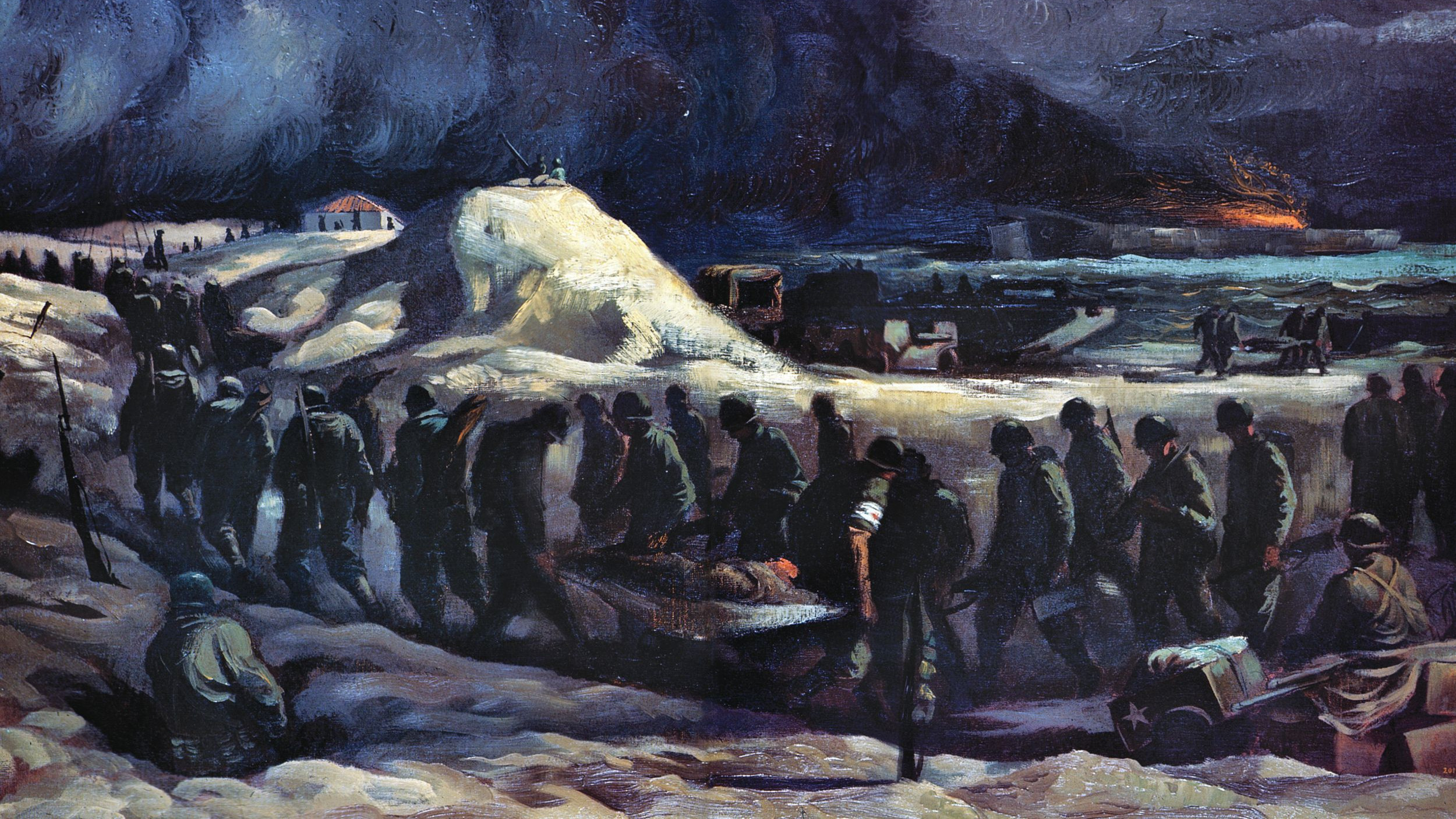

When the Allies advanced in Northwest Europe and Italy, the Luftwaffe was driven out of the sky, and P-38s operated as light bombers and reconnaissance aircraft, working in direct ground-support and interdiction roles, particularly during the Battle of the Bulge. They had done well against the Luftwaffe, but not as well as hoped. Their main achievement in Europe was in the bomber role, ripping open German trains and smashing Nazi troop convoys. Still, Luftwaffe pilots were said to have nicknamed Lockheed’s creation the “Fork-tailed Devil.”

It was in the Pacific that the P-38 would find its greatest success.

The Lightning began the Pacific War in August 1942 in the Aleutians, where pilots could take advantage of their long range to escort heavy bombers and attack the Japanese-seized islands, Kiska and Attu.

Later, P-38s arrived in the Solomon Islands. There the Lightning took on another legendary fighter—Japan’s Mitsubishi Zero and its Army knock-off, the Kawasaki Oscar. The Pacific squadrons had some of the same problems that their European brethren endured. Maintenance was difficult because the plane had two engines instead of one, and the Solomons’ tropical climate left everything damp. Twin engines doubled the chance that a hit could start a fire.

Despite these faults, the P-38 soon proved deadly. American pilot C.J. Jones had a simple endorsement for the Lightning: “With the P-38, you found a target and fired.”

The advantage the P-38 had in altitude, climb rate, and firepower to the Zero and Oscar enabled the Lightnings to dominate the Guadalcanal skies from the day they arrived, November 14, 1942. The Guadalcanal P-38s got to work a few days later, escorting B-17 bombers to attack Japanese airfields and naval convoys that steamed down “The Slot” to reinforce Japanese forces on the island.

On December 27, 1942, 12 P-38s charged into 20 Japanese fighters and seven dive-bombers heading for Guadalcanal, shooting down nine fighters and two dive-bombers for the loss of one Lightning. On January 6, 1943, several formations of Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks and P-38s attacked a Japanese troop convoy that had heavy fighter cover. The Tomahawks accounted for 28 Japanese planes, while the P-38s bagged 13 more. Three of the latter kills went to a young lieutenant named Richard Ira Bong, who would become the top American ace of the war with 40 kills.

It was the beginning of the American P-38 “fighter sweep” across the Pacific, and the Lightning would lead the way, spearheaded by Bong and his wingman, friend, and rival, Tommy Lynch, who matched Bong kill for kill. Lynch amassed 20 kills before being shot down himself in March 1944.

On March 1, 1943, in the Bismarck Sea, a Japanese convoy appeared north of New Britain Island—eight transports and eight destroyers jammed with 6,900 troops and supplies for Lae on the north side of New Guinea. It came into P-38 range on the 2nd, and 24 heavy bombers with 16 P-38 escorts attacked.

The next day the Americans tried again, with 109 aircraft, including B-25 strafers, 13 Royal Australian Air Force Beaufighters, and P-38s taking off from Port Moresby in New Guinea amid perfect weather.

Under relentless bombing and strafing, the convoy and its aerial escorts were helpless. Lynch led two squadrons of P-38s—his 39th and the 9th—down on the deck to hit the air escort of Zeros. The 39th shot down 10 Zeroes for three losses.

The bomber force did even better. They sank all eight transports and four destroyers.

The P-38 was now the dominant fighter-bomber in the Pacific, with the two top American aces, Bong and Major Thomas C. McGuire, matching each other, kill for kill. Despite the rivalry, they were great friends who often flew together over New Guinea. By April 10, 1944, Bong was up to 25 kills. He gained two more on April 12, and claimed a third, which had crashed in shallow water near Hollandia. U.S. troops found the wreckage shortly after, and Bong was up to 28 kills, which made him the American ace of aces.

Two weeks later, Bong, with 40 kills, was shipped home as a test pilot and recruiting tool, ordered not to see any more combat. On August 7, 1945, he was killed flying the new Lockheed Shooting Star P-80 jet fighter near their Los Angeles plant.

McGuire met a harsh fate, too. On Christmas Day, 1944, he shot down three Japanese planes, to bring his score up to 34. The following day, he bagged four more, to make his total 38. But on January 7, 1945, McGuire tried to assist his wingman, who had a Zero on his tail, flown by Shoichi Sugita, a Japanese ace with 80 kills. Violating the rules he taught his pilots in the squadron’s ready room, McGuire made a high-speed, low-altitude turn without dumping his 160-gallon wing tanks, spun in, and crashed, his P-38 exploding on contact.

There were many P-38 aces, and some survived when Washington realized their high kill numbers. Charlie McDonald shot down 27 Japanese planes, making him third-most in the Pacific and fifth overall. He survived the war, as did Gerry Johnson, with 22. He was killed on October 7, 1945, two months after Bong died, perishing the same way—testing a P-80. And George Welch, one of the very few fighter pilots who was able to get airborne at Pearl Harbor, moved up to P-38s and amassed 16 kills.

On April 14, 1943, Commander Edwin Layton, head of the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s cryptographic unit, presented Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief Pacific, with a decoded message that revealed that Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Combined Fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy and architect of the Pearl Harbor attack, was going to fly an inspection trip by air from Rabaul, Japan’s main base in New Britain, to the Shortland Islands on April 18. Yamamoto’s flight would bring him within range of Major John Mitchell’s 339th Fighter Squadron, based on Guadalcanal. They could intercept Yamamoto’s two planes, shoot them down, and hopefully take Japan’s keenest nautical mind out of the war.

The assignment was given to Mitchell and the 339th Fighter Squadron, whose P-38s would have the range for the ambush.

Mitchell planned to take six P-38s under his own command to tackle the fighter cover, while Captain Thomas Lanphier led four P-38s to hit the bombers. They plotted a course that would have the Lightnings fly south from Guadalcanal, then northwest, then northeast, and ambush Yamamoto’s planes as they were over Bougainville and preparing to land at the Shortlands airfield. Everybody would fly in on the deck and make use of the P-38’s climbing speed and high firepower to bring down the enemy. Finally, strict radio silence would be observed.

Mitchell’s planes took off early on April 18, followed by Lanphier’s group, which consisted of his wingman, Rex Barber, Jim McLanahan, and Joe Moore. But as McLanahan’s plane trundled down the fighter strip, it blew a tire in a loose spike in the matting and could not take off. Lanphier’s team was down to three planes. Ten more P-38s followed as additional top cover. Everybody was airborne by 7:25 a.m.

Mitchell led the whole force in a gentle curve seaward, down on the deck, in formation. Then Moore had trouble—his engine sputtered as he switched from his main tanks to his drop tanks. He couldn’t get fuel from them. Lanphier motioned him to turn back.

Down two planes, Mitchell ordered two planes from the 10-plane top-cover unit, flown by Lieutenants Besby Holmes and Frank Hine, to replace the missing pair in Lanphier’s unit. They had never flown with Lanphier, but there was no alternative.

At 9:33, Lanphier and Mitchell saw Bougain-ville’s jungles beneath them and Shortland Island just south of that, but no Yamamoto. Then Lieutenant Doug Canning broke radio silence in a low, steady voice to say, “Bogeys 11 o’clock. High.”

The Americans came under antiaircraft fire from the ground but wasted no time. Lanphier and his three colleagues swooped on the bombers. “I felt my hands getting clammy on the control column,” he said later. “What a time to get nervous, I thought!” Holmes was amazed at being able to shoot down Yama-moto. Mitchell barked at Lanphier, “All right, Tom. Go get him. He’s your meat.”

Incredibly, the Japanese had not seen the Americans—they were still flying along easily. Lanphier was nearly level with the bombers, and then he saw two Zeroes drop their own belly tanks and swoop toward him. As he and Barber closed in, Lanphier “wondered with stupid detachment if his bullets would start hitting me before I could get my guns up and into his face.”

Mitchell told Lanphier, “Leave the Zeros, Tom. Bore in on the bombers. Get the bombers. Damn it all, the bombers!”

Yamamoto’s plane began diving toward the deck, seeking safety at 200 feet. P-38s had tremendous diving ability, and Lanphier’s planes roared down on them. Barber opened fire at a Betty, making it a personal battle with the bomber’s tail gun, which never fired. Barber kept stitching up the bomber, and part of its tail section and rudder flew off. The Betty did a quarter snap to its left, and both planes were now near the treetops. The bomber lost speed rapidly, and Barber shot past. He looked back to see black smoke rising from the jungle and knew he had a kill.

Barber also knew the Zeroes would be coming after him, so he “hunched under that armor plate” as three Zeroes chased him from his right. Barber began climbing while two P-38s from his top cover stormed down to save him.

Meanwhile, Lanphier saw a shadow moving across the treetops beneath him—it was the other Betty bomber. He dived on it to treetop level, throttled back, and found two Zeroes diving at him from his right. For a moment, it looked like three fighters and a bomber would collide. But Lanphier was determined to get a shot at the bomber and did so. The Betty’s right engine and right wing began to burn. The right wing exploded, and the bomber plunged to the ground.

Lanphier turned into the Zeroes attacking him as they dived. They slowed down, and Lanphier escaped on the deck. Behind the P-38 pilots lay chaos, 20 Japanese dead, including Yamamoto, hit by a bullet in the back of his neck. It took a day to find his wrecked Betty, and his body was identified by the jeweled samurai sword he held. Everyone on Yamamoto’s plane was killed. The other Betty had three survivors. In addition, three Zeroes were shot down.

The Americans lost only one plane and pilot, Hine, caught by a Zero. But for the next four decades, the pilots who flew the mission and their supporters would argue over who could actually claim the Yamamoto shootdown. The issue remains unresolved to this day. Lanphier and Barber fought over it until the former’s death.

One thing they and all the other P-38 pilots of World War II agreed upon was the excellence of the airplane. It was a plane for two roles in two theaters: highly successful fighter-bomber in Europe, blasting rail and road traffic; and dominating fighter over the Pacific. P-38 pilots enjoyed its many benefits in and out of battle.

But the best analysis comes from Japanese wartime navy air officer and postwar historian Masatake Okumiya, who described the P-38 Lightning simply as “an enemy of terrifying effectiveness.”

Author David Lippman resides in New Jersey and writes frequently on a variety of topics for WWII History.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments