By John Emmert

Decades of feature films and years of video games have created an image of the World War II American GI and Marine slugging it out against Axis foes with the M1 Garand semiautomatic rifle and the Thompson submachine gun, with the occasional M1 carbine thrown in for good measure. However, American troops, even well into 1944, could still be found carrying a vestige of early 20th century small arms technology, the bolt action M1903 Springfield rifle. Adopted long before most of the World War II generation was born, the M1903 was the designated substitute rifle if the M1 Garand was not available.

The Rifle Caliber .30 Model 1903 was adopted as the standard U.S. military rifle in 1903. Based on the Mauser manually operated bolt action rifle designed and produced in Germany, the M1903 was a five shot weapon with a 24-inch barrel intended to serve as a standard rifle for all services in an era when many countries issued long rifles to the infantry and short carbines for artillery and cavalry troops.

However, the M1903 was modified in increments over the following three years before its final configuration was decided upon. The original, integral rod bayonet was replaced in 1905 with a 16-inch sword bayonet design. Also, the graduated ramp rear sight mounted on the barrel just ahead of the receiver was replaced with a folding ladder rear sight in the same location but more applicable to long range target shooting. Last, the M1903 received a modified chamber to shoot the newly developed .30-06 cartridge.

Manufactured by the government arsenals at Springfield, Massachusetts, and Rock Island, Illinois, the M1903 was unofficially referred to as the Springfield, continuing in a long line of Springfield Armory designed shoulder arms. It was, however, the subject of a controversial legal battle between the U.S. government and the German Mauser company, which resulted in the U.S. paying damages to Mauser, even after World War I.

The M1903 had not been available in the numbers required during World War I. Even though production had been increased significantly, the U.S. Army was forced to seek more rifles elsewhere. The M1917 rifle, a British design built under license by Winchester and Remington, was issued in .30-06 and saw action in large numbers overseas. However, military politics played in the M1903’s favor and it remained the standard rifle after the war.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, John C. Garand, a Springfield Armory employee, sought to produce a practical, simple, weapon which could, as Alexander Rose described in his book American Rifle, with the mere pulling of the trigger “allow the rifleman to pull it again.”

The M1903, together with other bolt action rifles, require the user to frequently break his view of the sights to operate the bolt after firing each shot. Even with a skilled operator, the step of gaining a sight picture after being forced to break off, taking the slack out of the trigger, breathing, firing, operating the bolt, and repeating requires a certain amount of discipline and proper training. Considering that in the heat of battle the fact that even the best shots will fail to connect with their enemy in a stressful environment, and the operational simplicity of a semiautomatic rifle could appeal to a lot of military thinkers.

With a semiautomatic, the operator takes up a sight picture, breathes, presses the trigger, waits for his sights to come back on target, and allows the trigger to reset for the next shot. Also, semiautomatic rifles tend to have less recoil due to the mechanism soaking up much of the rearward impulses. This simpler battery of arms also brought with it the fact that the effective rate of fire was limited only by the skills and trigger finger of the shooter.

However, semiautomatics were more complex and expensive, and senior military officials believed that issuing such weapons would result in poor fire discipline and wastage of ammunition. Furthermore, early attempts to produce a semiautomatic rifle for general issue had resulted in portly, underdeveloped weapons that were inaccurate and unreliable. The merit of the bolt action was its mechanical simplicity. A bolt action like the M1903 could be fired and loaded indefinitely, hinging only on how quickly the operator would become fatigued.

By the mid 1930s, the United States Army, however, had evaluated John Garand’s service rifle, an eight-shot semiautomatic, which, although heavier than the Springfield, showed the promise of shaking the reputation of preceding designs. In 1936, after a series of tests and evaluations, the Garand was standardized as the Rifle Caliber .30 M1. This did not mean that the M1903 was automatically replaced. It would take years for the M1 to reach full production thanks to Depression era budget constraints, and the U.S. Marine Corps did not see the M1 as sufficiently superior to the M1903.

The M1903 handles slightly better than the M1 due to roughly a pound difference in official stated weight, 8.7 pounds compared to 9.5. However, the M1 was designed with some economy in mind, with the intent being to share as much equipment with the M1903 as was possible. The M1 was designed to take the M1905 bayonet used with the M1903, its clip size of eight rounds was the maximum capacity possible while still being able to use ammo belts issued with the M1903. Although this mindset did prohibit the M1 from possessing more radical features such as a detachable magazine, it likely worked out for the best considering the course of the war. Troops transitioning to the M1 would only have to trade in their old rifles.

The M1 was not perfect. Shortly after adoption and the initiation of full production, the M1 began to suffer from malfunctions, and the process of incorporating the fixes into the production line and refitting the weapons in service added delays to deployment. Also, the government further slowed debugging of the M1 by ordering investigations into the selection of the M1, and some called for further competitions to determine if there were better rifle designs. When war broke out in Europe in 1939, it was clear that the United States would have to rearm within two or three years in order to meet the threat.

The Marines were adamant that the M1903 suited their needs. In November, 1940, the Marines held a series of trials in which the M1 and the M1903 were subjected to an abusive, all out torture test including being exposed to both salt and fresh water, sand, and a complete immersion in mud. Not surprisingly, the M1 failed to pass the rigorous test, which was rigged in the M1903’s favor. To the Marine’s chagrin, they did find that the M1 compared favorably to the M1903 in terms of accuracy. The Marine prejudice against the autoloader would only die on a far away Pacific island, in one of the most intense campaigns of the war.

As Europe was engulfed in the Nazi onslaught, the U.S. military faced a severe shortage of small arms. The institution of the draft in 1939 and increased military funding meant that there were more men coming into the ranks than the military had anticipated. The military had only just fixed the flaws in the M1’s operating system, but even supplying Winchester with a contract to build the new semiautomatic rifle would not be enough. It would take time for the Springfield Armory and Winchester to streamline and speed up production rates. However, the tooling that had been used to manufacture M1903s at Rock Island was still in existence, and in November of 1941, Remington began producing M1903s using that tooling.

The early Remington M1903s were made to the high quality standards that had been expected of the M1903 since production had previously ceased in the 1920s. However, production rates were low due in part to worn tooling and in part because the rifles were made to production standards that were frankly too high. In early 1942, Remington began to integrate shortcuts in productions, substituting stampings and limiting machining operations where possible, creating the M1903M. Also, the flat gray parkerized finish replaced the glossy black parkerizing that had been used previously, as would become common throughout American wartime firearms production. However, the M model was still not simplified enough.

The M1903A3 was implemented by Remington and adopted by the military in May 1942 to create a serviceable yet cheaper rifle. Gone were the match grade target sights that had characterized the M1903. Instead, the 1903A3 featured a rear aperture sight mounted on the rear of the receiver, the furthest range setting being 400 yards. Also, the magazine well and trigger guard were now a single piece made from stampings and welded together. In 1942, Smith Corona Typewriter was assigned a contract to supplement Remington’s output of the M1903A3.

When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, the troops in the Philippines were largely equipped with M1903s, although a few M1s were in the hands of U.S. troops before the surrender on Bataan and elsewhere in the islands. For many who joined up both before and after Pearl Harbor, the first weapon they were issued was often the M1903.

Robert Edlin, a National Guardsman who had joined his outfit in 1939, said, “That ‘03 rifle kicked like a mule….” Even regulars in prestigious outfits like the 1st Infantry Division, “The Big Red One,” were forced to make due. Directly assigned to his unit at the end of 1940, Bill Willis joined the 1st Division and still had to face shortages. “We qualified on the rifle range with the Springfield ‘03,” he recalled in a later interview.

There were still those in the Army who resisted replacing the M1903 with the M1, old sergeants who did not want to change over to the M1 and did their best to bad mouth the weapon in front of the troops. The attitude was likely as poor, if not worse, among old salts in the Marines. Despite the fact that the Marine Corps had bowed to the inevitable and officially adopted the M1 just as America joined the war, it would take more than a year for the M1 to be issued to the Leathernecks.

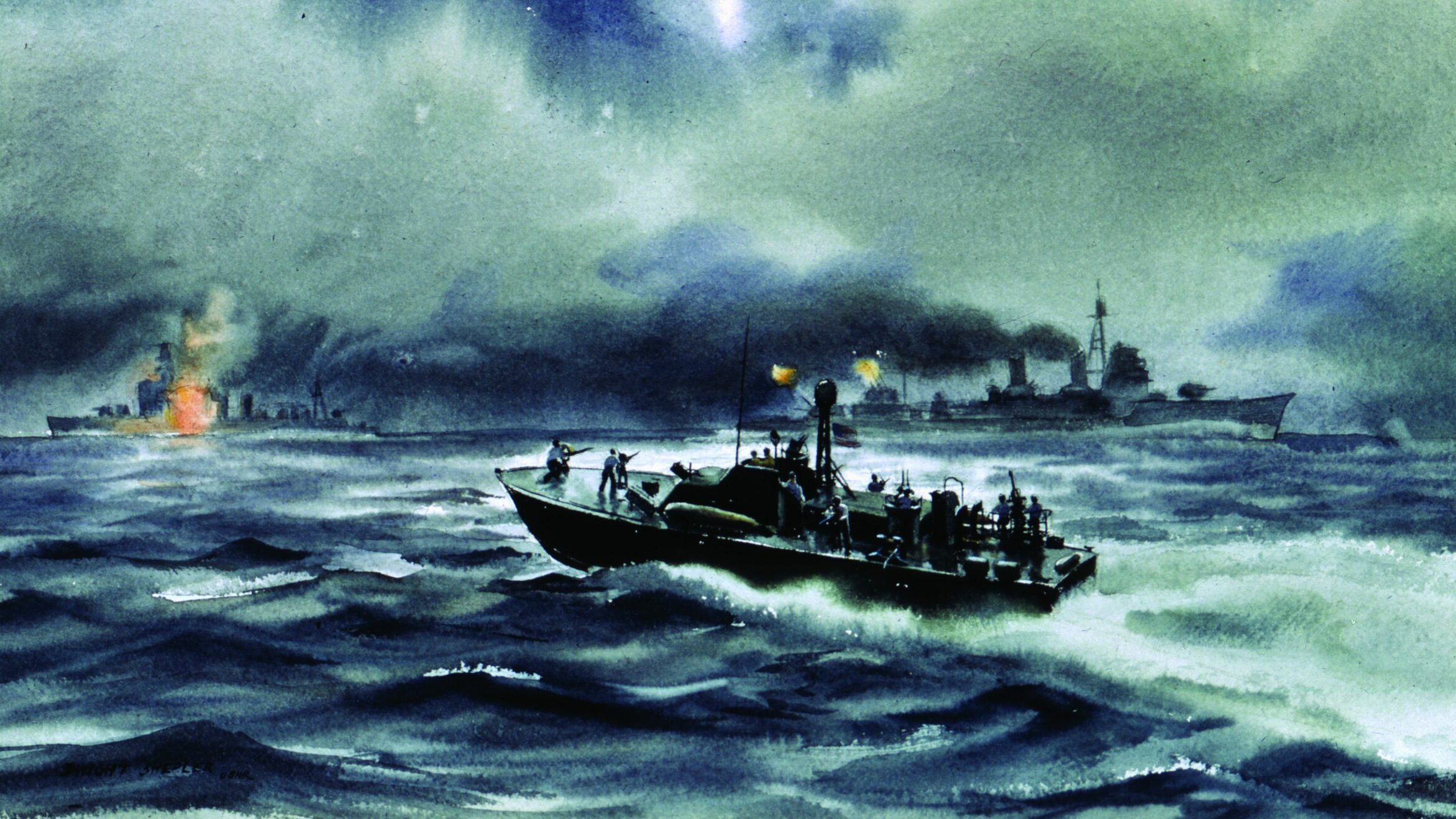

The 1st Marine Division was deployed overseas in the summer of 1942 in preparation to strike the first blow against the Japanese, the M1903 being the ubiquitous rifle. The Marines, both wartime and prewar, were quick to realize that their weapon of choice had a major drawback: its slow rate of fire. The Guadalcanal campaign, which began in August 1942, would pit the reinforced 1st Marine Division against the Japanese Army in a struggle over Henderson Field, the airbase seized to keep the Japanese from completing it.

Over the course of the battle, the Marines faced several hours-long Japanese “Banzai” night attacks, thankfully blunted or stopped due to the presence of the Browning M1917 .30-caliber water cooled machine guns around the perimeter. The Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) was also present on the squad level, but the average Marine in place along the line during such an intensive, all out assault would have been frantically operating the bolt of his rifle, praying that the machine guns on either side of him kept functioning or that the gun crew was not killed.

Patrols beyond the perimeter were fraught with danger, especially since the M1917 was far from being easily man portable. The arrival of U.S. Army units on the island to reinforce the Marines in later stages of the battle brought more than reinforcements. The firepower at the Army’s disposal on the individual soldier’s level was advertised to the Marines when the 2nd Battalion, 164th Infantry launched a counterattack on the far left of the 7th Marines during the Battle of Bloody Ridge.

As Eric Hammel wrote in his book, Starvation Island, “Light, medium, and heavy machine guns, and hundreds of new Garand rifles lashed back and forth along the shattered lines of men emerging from the carnage of the anti-tank fire. The Japanese never really got close to the Timboe’s Guardsmen, so telling were the American defensive fires.” After that demonstration, there was no going back for the Marines. It was not until well into 1943 that the M1 was on hand in sufficient numbers to replace all M1903s, and several photos exist showing the M1903 in use well into that year.

Further use of the M1903 was made in the squad support role as a grenade launching rifle. Using a special fitting clamped on the muzzle of a rifle, a finned adapter for a hand grenade, and a special blank cartridge, a grenadier could launch a bomb far further than he could throw it. It took ordinance time to develop a launcher for the M1, and even when it did the M1 was incapable of firing semi-automatic with the device fitted. Also, the en-bloc clip system meant that it was far more cumbersome to load the special blank in the M1 than the M1903, keeping the M1903 in service longer.

Even though the M1 was popular, the M1903 could still be found in large numbers in areas that had far lower priority. Italy and Burma were places where the M1903 was in widespread use well into 1944. Also, photographs exist showing troops reaching France after D-Day with an M1903 slung over their shoulder.

The U.S. military entered the war lacking a dedicated sniper rifle. During World War II, the typical solution to any lack of a sniper rifle was to equip a standard service rifle with a commercially available scope. The U.S. was no different in this regard. The M1, however did not readily adapt to a scope due to the top loading and ejection of its en-bloc clip. Also, demand for the M1 was simply too high to warrant sidelining significant numbers of them for modification and issue to snipers when the needs of regular infantrymen could not be met.

The U.S. Army chose the M1903A3 as the base platform to be used as a sniper weapon. The sights were removed, bolt replaced with a modified design capable of clearing a scope, and a variation of the Weaver 330 scope mounted atop the action. The ensemble was designated the M1903A4 (Sniper’s). Interestingly, the A3 markings were not removed from the rifle, kept in case the rifles as they were manufactured did not meet the standards of accuracy required.

The A4 was not readily liked by soldiers or the few Marines who were issued it. As could be expected due to the nature of the build, many were not what they could have been in terms of both accuracy and the durability of the scope. With the rushed nature of A3 production at Remington decades before precise production methods were discovered and implemented, barrel quality would have most certainly varied. To expect match grade accuracy out of such a weapon would have been unfair to the rifle.

The scope was likely a huge complaint. The Weaver 330 scope features a large, distracting reticule in the middle of a very narrow tube, and for the soldier the firing experience is something like looking through a straw. Low magnification and a narrow field of view would not have been atypical of the era, but even the Russian M91/30 sniper rifle’s PU scope has a slightly better field of view.

Perhaps the worst feature was the lack of iron sights. It has only been within the last couple of decades that scope technology has reached the point where magnified and electronic sights are in widespread use by frontline combat troops. The sort of durability that allows modern snipers to work without any iron sights with confidence did not exist. However, the M1903A4 was not an outrageous failure, and with optics chosen for the M1 sniper variants produced after the war could be found in Korea and afterward.

The Marines chose a far different approach when building their own sniper rifle. Using M1903A1 National Match rifles or other M1903s that showed promising accuracy, the armorers mounted an eight power Unertl target scope, leaving the iron sights on the rifle. Given no official designation, the rifle was simply referred to as the M1903A1 Unertl. The 8x scope was, however, given several inches of free travel to mitigate the effect recoil would have on the fragile instrument. As a result, the scope would have to be pulled back between each shot for the user to get a proper view of the reticule. The combination was not ideal but doubtlessly more consistently accurate than the A4.

The M1903 Springfield was the last in a long line of American shoulder arms to bear the name of the Springfield arsenal. It held the line during some of the darkest days of World War II, relegated to serve in the shadow of its replacement, the M1 Garand. In training and on the battlefield, the Springfield served quietly until the war ended and the remaining stocks were sold on the civilian market. Their availability, though, did provide many a youth growing up in the decades after World War II with a cheap, reliable, and durable rifle for hunting and recreation. They still show themselves in vintage target matches with old contemporaries from abroad, where men and women, young and old vie for local bragging rights in friendly sport. Perhaps it is a fitting retirement for the forgotten substitute.

John Emmert is a student graduating Thomas Edison State College with a degree in history. Hailing from Oregon, he has taken part in a number of high-power and vintage military rifle competitions. John operates a small historical blog and has finished his first historical novel.

My dad, Henry Gettman, earned a Distinguished Marksman’s Badge and was the #1 rifle marksman in the entire National Guard with his M-1903 in 1935-36 while serving with Company F, 161st Infantry Regiment, 41st Infantry Division, Washington Army National Guard. He had the rifle since his high school days in Walla Walla where he was on the ROTC rifle team 1927-31 and won hundreds of shooting medals with it while in HS and while in the National Guard from 1930-38, and as a civilian 1939-40. I have a newspaper article from 1940 where he mentions firing the M-1 for the first time at the Camp Perry National Matches. He said he liked the action but also mentioned that shooters who used it in competition the previous year (1939) didn’t care for it much. While my dad was in Vietnam in 1966, my brother got into his footlocker in the attic and he and a buddy sporterized the stock of the ’03 to make it lighter for hunting. I thought my dad was going to kill him when he got home from VN. I ended up giving the rifle to a friend in 1989 for hunting.