By Edward G. Miller

Hürtgen Forest. Chilling rain, freezing fog, mud, impenetrable forest. Unremitting misery for GIs and Landsers alike. War correspondent Ernest Hemingway famously called it “Passchendaele with tree bursts.” An unknown 4th Infantry Division soldier called it “hell with icicles.” One German general with years of combat experience called the fighting the worst he’d ever seen, including that on the Eastern Front.

Nearly 70 years have passed since mid-September 1944, when GIs from Maj. Gen. Maurice Rose’s 3rd Armored Division swept into the western edge of the forest. They were in headlong pursuit of the tens of thousands of Germans falling back through Belgium in disorder, desperate to reach the incomplete border defenses of the Reich. Many on both sides believed the end of the war in northwest Europe might be only weeks away. Maybe they could avoid fighting in a damp, cold Rhineland winter.

Expectations for an early end to the war degenerated into a brutal campaign of unending attrition within weeks of the GIs’ entry into Germany. The fighting in the hilly, forested land southeast of the city of Aachen brought little more than excessive losses with no appreciable gains in attacks aimed at doubtful objectives. No American general who ordered operations there expected the disastrous outcome that occurred.The first objectives were the roads and key terrain the generals thought vital to support attacks to cross first the Rur, then the Rhine River.

However, no attack could succeed without securing the flood control and hydroelectric dams that controlled the Rur. GIs fought in the Hürtgen Forest for almost three months before the objectives changed from roads and towns to these dams. Unfortunately, when these attacks began in mid-December 1944, the initiative was long gone and the Germans controlled the outcome.

Senior German commanders in Army Group B also had little understanding of the potential value of the dams. Their initial goal for defense of the border was simply to delay the Americans, whose persistence in fighting in the forest surprised them. They knew that by doing so the Americans gave up many of their advantages in air and artillery support. Only when corps and division commanders in late autumn finally learned about the upcoming offensive in the Ardennes did the value of the forest become starkly apparent. Here would rest the northern shoulder of that attack, and regardless of its outcome, the Americans could not safely cross the Rur unless they held the dams.

Historians, veterans, and even casual students of the campaign in Western Europe have been justifiably unkind to the American leadership and they have picked apart the tactical conduct of both sides. Perhaps what sets the Hürtgen Forest apart, at least for the Americans, is what it reveals about high-level decision making, recognition of goals, and consideration of alternatives.

Planning estimates for operations beyond Normandy saw the Allied armies reaching Germany by about D+330, or April 1945; instead they were at the border on D+97, or September 11, 1944. To support the drive to Germany, logisticians planned for echeloned logistics bases across France, Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg. This would enable short turn-around of supply transport vehicles making deliveries to field army rail- and truck-heads. The German collapse in France completely upset these plans; in fact, the Americans reduced production of large-caliber artillery ammunition. They also considered whether to plan the return of Christmas mail to the States. Senior U.S. Army leaders, particularly those in Washington, who urged the public not to be overly optimistic, lost out to wishful thinking.

Throughout August and into September, there was also an undercurrent of deep concern over the ability of logistical units to sustain the momentum. Troops and equipment were worn out and the attacking units lived hand to mouth. Corps artillery trucks augmented the transportation units, but this trade-off eliminated some fire support when it was needed during the approach to Germany. Overloading damaged many of the trucks and further disrupted the flow of supplies. Availability of repair parts then became a problem.

Even the equipment that was on hand, such as clothing, was not the type best suited for the cold, damp climate of northwest Europe with fall and winter coming on; poor decisions by Eisenhower’s quartermaster staff had already ensured that GIs would not have adequate clothing before the onset of bad weather.

Not only were supplies and clothing burgeoning crises—War Department manpower policies and faulty projections of losses would soon culminate in a theater-wide infantry replacement crisis. Transfer of men from rear-echelon and Air Forces ground units did little to solve this problem because the new men were not trained for combat. Units might even be better off without them. Probably more than the British and the other Allies, the Americans were victims of their own success. The time spent by staffs to ensure that operations in Normandy and northern France did not fail led them to neglect thorough planning for contingencies. Success depended on the Germans doing what the Allies expected them to do.

The first decision leading to operations in the Hürtgen Forest came in late August. Unwilling to compromise the initiative and gains made since the July-August breakout from Normandy, Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower directed the Allied armies to continue operations without a pause to await resupply. Looking ahead, the most important objective relating to longer term logistical sustainment of Allied operations was the port of Antwerp. Eisenhower and British General Bernard L. Montgomery decided that the capture of Antwerp and the key French ports on the English Channel must take priority over opportunities to complete the destruction of the enemy west of the German border.

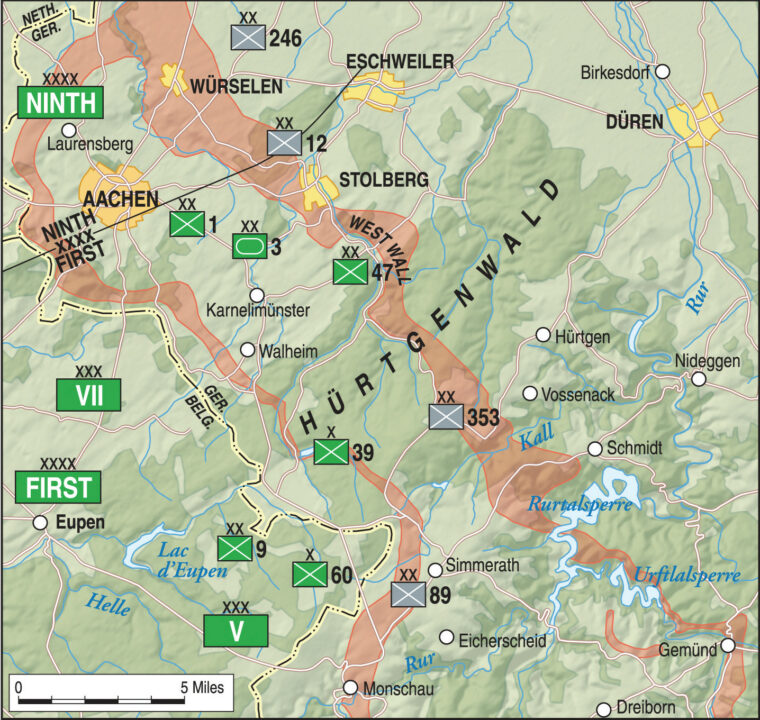

Eisenhower directed U.S. 12th Army Group commander, Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, to support the British attack north of the Ardennes that was aimed toward both Antwerp and the Ruhr. Bradley ordered Hodges’s First U.S. Army to attack generally north of the Ardennes. The Third Army (Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr.) aimed toward Lorraine and the German border opposite the Saar. Hodges in turn directed his two forward corps, the V (Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow) and the VII (Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins) to attack on either side of Aachen. The northern wing was the VII Corps, with only one armored and two infantry divisions. By the second week of September, it was on a collision course with the Hürtgen Forest.

Gerow’s troops, meanwhile, hit the German border defenses in the Schnee Eifel and to the south. Army group and field army operations and engineer planning staffs meanwhile produced estimates on the enemy situation and the resources needed to cross the Rhine and envelop the Ruhr. These staffs did not fully address intermediate objectives such as the Rur River, a necessary prelude to the Rhine.

Joe Collins, without a doubt Hodges’s favorite subordinate, focused on the German border defenses. He ordered the 3rd Armored Division and the 1st and 9th Infantry Divisions to penetrate the concrete fortifications of the West Wall in the Aachen area before attempting to capture the city. Based on intelligence reports and experience to date, driving through the border did not appear to be a particular challenge as long as the corps retained its momentum. These assumptions evidently carried over to estimates about the forest mass southeast of Aachen, known to the area’s residents as the Wenau, Roetgen, and Hürtgen State Forests.

Breaching the border and gaining the Rhine plain required the First Army to secure a road net adequate for conduct of logistical support. Collins understood the tenuous situation with his supply lines and, over Gerow’s counterarguments, Hodges approved Collins’s request to continue the attack by reconnaissance in force through the border defenses. Gerow’s corps likewise had only one armored division and two infantry divisions, but it operated on a much broader zone in Belgium and Luxembourg. Gerow could not concentrate his combat power to the extent that Collins could.

Intelligence reports most often noted the weakness of the enemy, though no one could predict with certainty how strongly the Germans could hold the West Wall. Nor could they predict with accuracy the resilience of the German Army.

Meanwhile, residents of the border villages prepared for the fight. Helene Hermanns of Mützenich, a village on the fringe of the Hürtgen, wrote in her diary on September 12, “German soldiers are in the village. Young men with machine guns. Hungry and tired, they came to our door and asked for a loaf of bread. They are here to defend our town.”

Though time remained on the side of the Americans, they did not know the initiative was about to shift to the Germans.

That same day, a few miles from Helene Hermann’s house, Lt. Col. William B. Lovelady’s tank-infantry task force of Rose’s 3rd Armored Division was approaching the border as part of the reconnaissance in force. His troops passed through the concrete obstacles that marked the West Wall defenses and immediately hit strong resistance near a dam and reservoir. At that time the Americans had no idea just how important the flood control dams in the area were to their plans. Instead, Bill Lovelady’s men consolidated their gains, set up outposts, and prepared to exploit their penetration of the border. So far, so good.

Logistics dictated the pace, power, and extent of the Allied attack into Germany. Since the forested area occupied a portion of the First Army’s axis of attack, its limited road net became an important concern. Capture of these roads and the villages that controlled them became the focus of operations. They did not link the Rhine crossings with the objectives necessary to reach that river—the Rur River and the series of flood control and hydroelectric dams buried in the woods. The larger dams controlled the level of the Rur which, when not at flood stage, was just a few yards across. If the Germans flooded the Rur after the Americans crossed, units isolated on the east bank of the stream would be open to defeat in detail—and at flood stage, the river’s width might grow to half a mile or more.

Like Task Force Lovelady, the rest of VII Corps was worn out by the third week of September. The reconnaissance in force sputtered to a close with the corps half in/half out of the West Wall. Yet the Americans remained confident that perhaps one more drive would break the developing thin crust of enemy resistance. The problem was that much of First Army’s combat power was becoming tied up in the Hürtgen Forest.

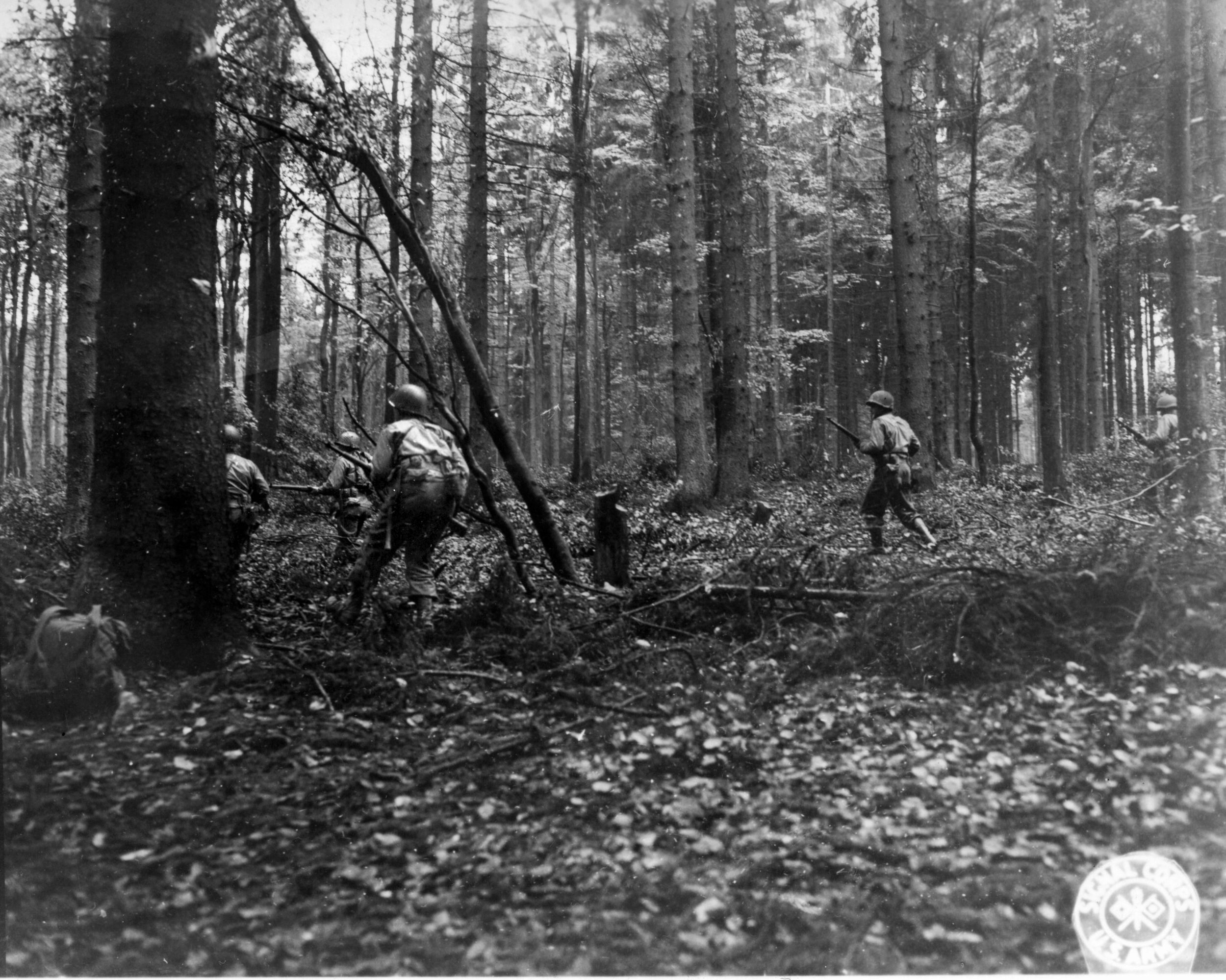

Concurrent with the attack of Task Force Lovelady, elements of Maj. Gen. Louis Craig’s 9th Infantry Division tried to sweep the lower half of the forest. Lack of troops forced Collins to divide the division into two large elements. One infantry regiment, the 47th, operated on the northern fringe of the forest, supporting the 3rd Armored Division. The 39th and 60th Infantry Regiments pushed ahead in the center of the forest. The 60th reached Germany after having sustained significant and un-replaced losses in riflemen while crossing the Meuse River in Belgium. It was simply impossible for two virtually unsupported infantry regiments to sweep an area of forest so dense that the trees shut out much daylight even on the sunniest days.

Rifleman Billy F. Allsbrook recalled, “All I saw were trees, firebreaks and more trees.” A rifle battalion executive officer later remarked, “Conditions in the interior were such as to cause opposing forces to come within fifty yards of each other before either could discern a target at which to shoot.” Six decades after the fact, Hubert Gees, a 19-year-old messenger in the German 275th Infantry Division, was unable to speak of what he saw there without tears.

September turned into October and the skies grew steadily gray as American commanders decided to try once more to break through the center of the forest to gain roads that could sustain their drive to the Rhine.

It was then, during early October, that the fighting in the forest became less a “battle” than it was a campaign without a clear objective. Still without enough combat power to tip the balance in their favor, the two regiments of the 9th Infantry Division tried to drive through the forest and take the key road running through the village of Hürtgen. From there, they would be within striking distance of the next objective, the important crossroad town of Schmidt, which commanded the western approaches to the largest of the Rur dams.

Yet, as vital as this and the adjacent dams were, they were not an objective of the attack. Even had they been, the VII Corps was not strong enough to physically secure them or to even control them by fire. Collins needed at least another infantry division, significant artillery and armor support, and several days of good weather. Hodges could not provide such reinforcement to Collins without significantly altering his broader plan, which also involved securing the approaches to the Rhine in the strongly defended open country north of Aachen.

Finally, Hodges’s boss, Omar Bradley, commander of 12th Army Group, had to be prepared to support the Allied airborne operation in Holland, maintain pressure on the Germans throughout the Ardennes-Hürtgen region, and to keep Patton moving in eastern France. Success in the Hürtgen, if fighting was to continue there at all, depended on a very weak German defense. However, the forest was a great equalizer of combat power and even weak German units could draw much GI blood.

The next round of hard fighting––between October 6 and 16––yielded little. If the Americans were not already convinced the Germans would control the outcome of the forest fighting, they should have been. German defenders fought from familiar ground, with artillery and mortar reference points precalculated to speed their fire. Their log and dirt-covered bunkers made excellent fighting positions. American leaders from squad to company found it extremely difficult to control their troops; resupply during combat was virtually impossible.

Because of the artillery tree bursts, mines, and mud, evacuation of casualties was as dangerous as direct combat. It was not unusual for troops to be wounded again on their way to a battalion aid station or casualty collecting point. What began as coordinated infantry-tank attacks often devolved into broken, dispersed infantry-only combat at close range against a nearly invisible enemy.

So brutal was it that the Americans took six days to gain just two miles from their line of departure to the north-south road leading through Germeter and Hürtgen (town) to Düren. On October 16, when the hell finally let up, they were about a hundred yards beyond that road. Devastated units on both sides drew back exhausted and, in some cases, near the breaking point.

Eisenhower and his subordinates faced a continuing dilemma as October wore on. The Germans still controlled access to the great Belgian port at Antwerp. In Allied hands, its cargo throughput capacity could ensure continuation of a major attack into Germany as long as logisticians could synchronize cargo deliveries with the arrival of combat units.

Intelligence estimates favored continued operations despite the impending onset of winter. What the supreme commander called “an unremitting offensive” would further drain German troop and matériel reserves and almost certainly shorten the war. His controversial broad front approach was still the strategy underpinning the campaign, and it made sense to the extent that it was simply impossible for the Germans to effectively concentrate strength everywhere.

First priority was a general buildup along the Rhine that would begin in early November with an attack by First Army to gain a crossing south of Cologne. Other elements of Bradley’s 12th Army Group would either support the First; or in the case of Patton’s Third U.S. Army, continue operations aimed at the Saar.

The First Army had priority since its ultimate goal was encirclement of the Ruhr industrial area from the south. Montgomery’s 21st Army Group would focus on the capture of Antwerp before it joined the attack. Its succeeding goal was encirclement of the Rhine on the north. In short, concerns regarding the logistical situation (e.g., Antwerp as an example) did not dictate the decision to continue the attack into Germany. However, it is clear that commanders were deeply aware of the need to ensure uninterrupted sustainment of Allied combat power.

Key to the German Army’s ability to withstand attrition was the cohesiveness of their divisional and corps staffs. Here the Germans excelled in their ability to control and reform shattered regiments and battalions, and direct them to the most threatened areas of the front. Their ability to buy time through extremely effective use of their damaged road and rail transportation system was without peer as 1944 drew to a close.

One of the German units facing the Americans in November was General der Infanterie Erich Straube’s LXXIV Corps under Seventh Army (General der Panzertruppen Erich Brandenberger). Their keen ability to hastily reorganize a command and control structure, shuffle or dissolve headquarters lacking subordinate units, and unhesitating transfer of sub-par soldiers out of the divisions and other maneuver units they wanted to keep reasonably strong (such as panzer and panzergrenadier) went a long way in equalizing the balance of power in the forest.

Personnel accountability and poor training were inescapable problems, particularly in the units filled with Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine replacements. Such conditions forced small units to remain in the line, prodded by exhortations to fight to the last round, and then to continue to fight hand to hand. Such thinking would not have counted for much in less difficult ground.

Another equalizer was the Heer’s (German Army) emphasis on the selection and training of field- and company-grade officers and senior noncommissioned officers. Even the relatively untried and underequipped Volksgrenadier divisions, often derided by historians, could perform reasonably well with excellent small-unit leadership. These organizations also benefited from standardization of small arms and crew-served weapons.

There were spot shortages of weapons and vehicles as these units entered the line in late 1944, but even Volksgrenadier divisions could effectively employ their small arms in the defense with devastating results. Despite years of Allied air attacks, German industrial output at the time remained high enough to impact the pace of operations. Specific figures for deliveries to units fighting in the Hürtgen Forest are incomplete, if they exist at all.

Yet German records and American reports of units in the Aachen area indicate that German artillery strength was impressive even by American standards. For example, one corps operating on the northern fringe of the forest in October-November had up to 250 available artillery pieces. While the U.S. First Army units opposite this German unit had a significant advantage in numbers, ammunition was strictly rationed in October because commanders wanted to build up reserve stocks for later operations. Heavy guns (8-inch and 240mm, for example) were rationed to an average of less than four rounds per day.

As hard as the forest fighting was in September and October, nothing prepared the Americans for what they would face in the first half of November during a preliminary attack to ensure a firm south flank for the big First Army offensive.

Once more, only a single division, though strongly reinforced this time, was available to strike the high ground around Schmidt. Yet again, only the terrain, not the largest of the Rur dams, was the objective of the 28th Infantry Division when it jumped off on November 2. The 28th’s commander, Maj. Gen. Norman D. Cota, a hero in the Omaha Beach fighting, went into the action knowing the risks. He told an interviewer not long afterward that he did not think his men had a gambler’s chance of success.

The 112th Infantry Regiment’s attack began with excellent prospects as it rolled across objectives the 9th Infantry Division had not secured in October. The villages of Germeter, Vossenack, and Kommerscheidt (a few hundred yards from Schmidt) were in American hands by the night of November 3, and Cota received congratulatory messages from colleagues and superiors. However, his 110th and 109th Infantry Regiments were deadlocked on either side of the successful penetration. Also unknown to the Americans was the presence of strong German reserves, directed to the area as a result of a coincidental high-level staff exercise with a scenario that by chance duplicated the actual events underway in the Hürtgen Forest.

A sense of unease settled on the GIs of the 112th during the night of November 3-4. Engineers were unable to improve the single trail linking Schmidt to Germeter, and only a handful of tanks and tank destroyers were en route to the infantry by morning. It was too late anyway, because about 7:00 am the Germans blanketed Schmidt with artillery, followed by armor. Within a few minutes the panzers were firing directly at American foxholes and the situation was sheer bedlam. GIs reformed a weak defense at neighboring Kommerscheidt, where the U.S. armor delayed what ended up as a total breakdown of the defense.

Meanwhile, the 2nd Battalion of the 112th was subjected to four days of constant shelling and exposure to freezing temperatures. Soldiers reported that German artillery and armor emplaced on a ridge just four kilometers away could fire with near impunity at specific foxholes. When the breaking point came early on November 6, the battalion gave much of Vossenack back to the Germans. Cota now had to reinforce the defenses there, and all he had available was his weak 109th Infantry Regiment, which had been unable to punch through thick minefields and stubborn defenses northwest of Vossenack. Its rifle companies were nearly all down to platoon strength. So were those of the 110th to the immediate south.

These events caused a near emergency within V Corps. Hodges authorized General Gerow to attach a regiment of Maj. Gen. Raymond O. Barton’s 4th Infantry Division, then en route to VII Corps, to the 28th Infantry Division; it replaced the 109th Infantry, northwest of Germeter on November 6. Swallowed up in a dense forested plateau, company commanders, platoon leaders, and NCOs of the rifle companies of the relieving 12th Infantry Regiment spent most of their time simply trying to control unsuccessful limited objective attacks.

Troops of both sides were intermingled; combat often took place between units that were only yards apart, and some men simply disappeared. It might have been the GI equivalent of the Civil War’s Muleshoe Salient at Spotsylvania. One German counterattack separated two rifle companies and surrounded a battalion command post, and the regiment was split into five pieces by November 9. The 12th Infantry Regiment soon withdrew for reorganization, having gained little if any ground.

Cota’s 28th Infantry Division and its attachments, meanwhile, lost almost 6,200 of about 16,000 assigned and attached men on November 2. German casualties are harder to assess, but likely exceeded 3,000. The Germans had forced the south flank of the upcoming American attack to rest on ground well distant from the Rur River.

The largest air attack of the war in direct support of ground troops, Operation Queen, was initiated on November 16. While it ultimately failed to secure Rur crossings and did not target the dams anyway, the attack resulted in the most widespread fighting of the campaign. It cost the Americans nearly 25,000 of the nearly 100,000 GIs fighting in and near the forest.

Unfortunately for the GIs on the ground, the need to avoid “friendly fire” casualties like those suffered during the Operation Cobra air attack in Normandy led to positioning of the bomb line well behind the Germans’ forward positions. While this spared First Army GIs considerable harm at first, it also protected the enemy.

Most VII Corps GIs fighting in the forest found it hard enough to just survive. For example, between November 16 and December 4, the three rifle battalions of the 4th Infantry Division’s 22nd Infantry Regiment went through 10 commanders—the 2nd Battalion had four commanders in one day, including two wounded and one killed. One rifle company had six commanders; another had five over the course of three weeks.

The first three days of combat (November 16-18) cost the regiment 391 battle and 63 nonbattle casualties, numbers that include 28 officers and 110 NCOs. Such were the effects of stubborn German resistance, weather and the brutal terrain. Day after day, the GIs picked themselves up from water-filled foxholes and stepped into a shroud of mist, never drying out, and eating cold C-rations if they had time.

Resupply and medical evacuation routes were narrow, mine-filled forest trails and firebreaks because the area’s few roads were often impassable. Armor necessarily remained well behind, and though direct support artillery battalions fired thousands of rounds, the limited visibility prevented accurate adjustment and effectiveness. German units suffered equally—some simply evaporated as their survivors died or were captured. Artillery duels lasted for hours, literally blasting the woods to splinters.

It took the 22d Infantry nine days (November 16-25) to penetrate less than six miles of forest to reach the village of Grosshau, alongside the key highway through Germeter and Hürtgen to the Rur crossings at Düren. By then, according to one source, “a fatalistic attitude began to permeate the regiment.”

Leader casualties were particularly damaging—by November 26, Company C had only one veteran officer and less than a half dozen NCOs left. The vicious fight for Grosshau itself dragged on through November 29. Fifty percent or higher casualties despite replacements were the rule, due in part to the extreme difficulty of getting tanks and tank destroyers through the woods. German mortar and antitank fire often disrupted combined armor-infantry operations when they occurred. And even that was not the end, for beyond Grosshau was the village of Gey.

On December 1, one rifle company suffered 65 percent casualties, with many of the GIs being killed outright. The company commander was forced to put privates first class in command of two platoons. Between November 16 and December 3, the regiment lost 86 percent of its assigned strength.

By November 21, meanwhile, the situation with the 12th Infantry, rushed into the forest under near emergency circumstances near Vossenack, was such that a regiment from Maj. Gen. Donald A. Stroh’s 8th Infantry Division (V Corps) replaced it. This regiment, the 121st, finally captured the town of Hürtgen at the end of November.

Texan Paul M. Boesch, a former professional wrestler who was now a rifle company lieutenant in the 121st, recalled, “From house to house we fought, each house a determined strongpoint until the Germans inside at last became convinced they could hold no longer and still live.”

Each house and store, and in some cases, each room, became a battleground. When they finally caught up with the riflemen, American tanks first sprayed the windows and doors with machine-gun fire, then used their cannons to blast a hole for the GIs. Sensing there was little hope for escape, some Landsers fought until the end. Others waited for an American to appear, then surrendered. German mortar and artillery fire continued even after the town fell.

One look at the terrain through which the GIs attacked the town of Hürtgen explains why it took a week to gain just a mile and a half—an almost sheer vertical valley wall canalized a battalion axis of attack to the width of a single narrow road leading sharply uphill onto a small forest-cloaked plateau. There was no other usable approach given the ground captured by that time. Previous decisions to operate in this terrain without significant advantage in combat power led to continual operations on frontages that were sometimes literally squad- if not soldier-wide. And in areas where broader front operations were possible, the Germans still were able to control the pace of events.

Even after the 121st Infantry secured Hürtgen, there remained work to do to get the V Corps to the highest ground in the vicinity from where it could help protect the south flank of the VII Corps main-effort attack to the Rur.

The first week of December arrived with the tired regiment securing attack positions for elements of Maj. Gen. Lunsford E. Oliver’s 5th Armored Division and the 2nd Ranger Battalion’s attack to capture Hill 400. This elevation was just over three miles by road from Hürtgen, but its capture took another week of misery at a high cost in soldiers and armor. Hill 400 offered a commanding view of part of the reservoir created by the big Schwammenauel Dam, but by the time the hill was under American control, the troops could do nothing more than establish observation positions. They did not have the combat power to exploit the attack.

Concurrently with these operations, Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner’s 1st Infantry Division fought on the northern reaches of the forest to sweep the area east of Aachen.

Conditions here differed little from those to the south: tree bursts, water-filled foxholes, very limited visibility, and German counterattacks. Fighting in two villages in the north are good examples of what happened even when the GIs broke free of the confines of the dense forest. At Hamich, a strong counterattack by elements of the 47th Volksgrenadier Division, supported by armor, slammed into a battalion of the Big Red One’s 16th Infantry Regiment. Fighting was so intense and close-in that little more than rubble was left of the town.

Nearby Merode proved disastrous. Platoon leader Sidney Miller (Company F, 26th Infantry, 1st Infantry Division) recalled some years later, “A new CO, two new inexperienced platoon leaders, and a large number of new replacements didn’t appear to me to be the right combination of a cohesive fighting unit. It had all of the earmarks of a disaster, which it eventually turned out to be.”

Getting to Merode was hard enough. Miller was fortunate that of two 120mm rounds that landed close to him, one failed to explode and one caused only a concussion. Two of the company’s three platoons were nearly destroyed in the forest before reaching the village. After the GIs entered the buildings, German mortar and artillery fire cut them off from the rest of the battalion and, during the evening of November 29, a counterattack supported by panzers overran them.

Tanks fired directly into the windows and blew down walls. American Shermans contributed nothing because they were unable to negotiate the trails and firebreaks in time to shift the balance of power. Entries in the 26th Infantry Regiment’s operations journal reflect the desperation on the night of 29-30 November 29-30:

2033 hours: “Have 2 companies in town … shelling is heavy along road. Road is blocked by a turned over [U.S.] tank.”

2120 hours: “[Companies] E & F are in town … We have to have the road open tonight.”

2205 hours: “Our casualties have been very heavy these days.”

November 30, 0030 hours: “There is [sic] one to two enemy tanks and some infantry in town … I am afraid the men in the town are going to take a beating, but there is nothing we can do about it.”

0354 hours: “We heard that ‘F’ Co. runner come back saying that there were at least three [German] tanks in town.”

0530 hours: “What’s in town may be annihilated now.”

0850 hours: “We are out of communication at present.”

1030 hours: “[C]an’t imagine a whole company getting gobbled up.”

The First Army attack that began on November 16 with such high hopes had degenerated into a brutal fight of attrition where success was measured in gains of a few yards of muddy earth. Time and terrain were on the side of the Germans.

Only after prospects of success had dimmed did Eisenhower speak to Bradley about the issue of the dams. General Hodges at first called for air attacks to breach the largest (Urft and Schwammenauel), but air officers argued that the attacks would not be worth the effort. The first mention in a 12th Army Group situation report of any type of deliberate air or ground attack on a Rur dam came on December 4: “The RAF was assigned the mission of bombing the dams in the vicinity of the ROER River.” There was no reported damage on either of the two largest ones, and the weather forced cancellation of a second attack that day. A December 5 attack failed to breach the Urfttalsperre.

Bradley and Hodges then turned to Gerow’s V Corps to make the first ground attack deliberately aimed at the Schwammenauel and Urft dams. The new 78th Infantry Division, under Maj. Gen. Edwin P. Parker, committed two regiments and attached armor to the drive, which began on December 13. That same day, an unnamed prisoner said the Germans were prepared to open the flood gates on order. Yet aerial reconnaissance reported that the enemy had removed previously identified antiaircraft guns from the vicinity of the dams.

It is impossible to know for certain if such information might have led Bradley and Hodges to wonder if the Germans had decided not to defend the dams, and in some way to justify their lack of focus on them. Whatever the thinking on the American side, by now senior German officers realized the importance of both the dams and the forest to their imminent offensive in the Ardennes and they would in fact continue to defend them.

Still, the V Corps attack had to go on because the Americans were irretrievably committed to the forest, the dams would not go away, and the Rur River, gateway to the Rhine/Cologne plain, remained under German control. It was too late to bypass the dams, and it was clear that air attacks, especially at that time of year, had little value.

A swift and powerful German counterattack at Kesternich, a village sitting on high ground overlooking the western approaches to the Urft Dam, cost elements of two rifle battalions of the 78th nearly 1,000 casualties in just three days (December 13-15). Operating on the southwest fringe of the forest mass, Maj. Gen. Walter M. Robertson’s 2nd Infantry Division sustained about 1,500 casualties trying to capture an important crossroads on the route to the Urft Dam.

Now, after three months of fighting in the Hürtgen Forest, the Americans had to turn their attention in another direction with the start of the so-called “Battle of the Bulge,” which began on December 16. Limited engagements in the forest area continued, and troops on both sides suffered casualties from combat and exposure in the harshest winter in decades.

Had the Germans not wasted so many resources in the Ardennes, they might have forced continuation of fighting for the dams until early spring 1945. Still, it was late January, well after the worst of the fighting in the Ardennes was over, before the Americans could renew their attacks, first against the dams and then the Rur River line.

Why did it take so long for commanders and their staffs to recognize the importance of the dams compared to the forest and its roads? Certainly logistics remained uppermost in their thinking well into the late autumn. Even so, some staff officers realized the impact of a flooded Rur valley. An October report by the 9th Infantry Division’s G-2 (Intelligence Officer) and division engineer warned about the impact of floods caused by opening the floodgates on the Schwammenauel and Urft Dams. The U.S. Ninth Army’s engineer staff issued a similar warning in late October. Bradley’s army group staff engineer on November 4 referenced a prewar German plan to cause a slow flood of the big Schwammenauel reservoir.

Twelfth Army Group staff estimates through September mentioned the goal of gaining the Rhine in November, but Bradley’s G-3 (Operations Officer) urged completing the destruction of German forces west of the Rhine before crossing it. Bradley, on October 8, ordered Hodges to “continue your attack to the stream [Rur River] running through Düren,” but he added that First Army should do this only if the “going is easy.” Otherwise, Hodges must delay until the British resumed operations so that the Germans would face multiple threats.

Meanwhile, Hodges remained committed to keeping broad pressure on the Germans with the limited resources available to him. He evidently failed to recognize the importance of the dams to any attack designed to cross the Rur. Whether due to an absence of vision, or a stubborn, single-minded focus on objective, Hodges’s mid-November attack had dragged on for nearly two weeks before an army group situation report called the Rur “a strong river barrier” and noted the importance of the dams.

By then, the Americans were concerned that the Germans had concentrated armored reserves to counterattack any crossing. Compounding the lack of planning focus, a comparison of some unit situation reports with actual events indicates that when Hodges did get out of his headquarters, he did not always receive an accurate picture of conditions within the frontline units. Perhaps the corps and division commanders did not always know the situation themselves. One reason that orders to attack continued was that these reports usually characterized division and regimental combat effectiveness as “excellent” despite the realities on the ground.

The forest and dams became a matter of open concern at corps and higher levels only in mid-November. Synopses of staff updates to Bradley mention events in the Hürtgen Forest and concern about the condition of the largest dams; however, operations were irretrievably aimed at other goals. Discussion of the forest during Bradley’s staff updates usually centered on the progress of division-level operations, not the status of the dams. Yet whatever the context, specific discussion of the forest fighting evidently did not lead senior commanders to reconsider the objectives. Further, while there was also mention of the Rur River, discussion seems to have involved ways to force the enemy to withdraw across the river, not on securing the dams.

Finally, when renewed operations began after the Americans were assured of success in the Ardennes, everyone clearly understood the importance of the Rur dams. The positioning of U.S. forces at the easternmost end of the Bulge placed significant combat power in the area. Shifting field army and corps boundaries in early 1945 put the First Army once again in charge of the Hürtgen battleground. Plans called for a drive to cross the Rur to begin on February 10 as a prelude to a general offensive to the Rhine.

Of course, everyone now fully understood the importance of the dams to such operations, and these plans called for preliminary attacks aimed specifically to capture the dams by ground attack. The zone of attack would be across the relatively open high ground on the south fringe of the forest. Here waist-high snow drifts complicated operations, but by February 2 the 78th Infantry Division and its reinforcements were in position to continue to the Schwammenauel Dam. They had in the meantime encountered a familiar enemy from December 1944, the remnants of the 272nd Volksgrenadier Division, and retaken Kesternich after another extremely vicious fight. To the south, it was somehow fitting that the veteran 9th Infantry Division, among the first to fight in the forest, secured the Urft Dam on February 4-5.

Bitter cold and snow gave way to driving rain as the 78th meanwhile fought for successive objectives to clear the approaches to the dam. It also recaptured Schmidt, lost to the 28th Infantry Division three months before. General Parker’s troops endured mixed-up orders and too much involvement by the V Corps (now commanded by Maj. Gen. Huebner) staff due to the pressure to secure the Schwammenauel dam and prevent the Germans from flooding the Rur before the planned February 10 start of Operation Grenade, the attack to cross the river.

Still, late on February 9 the division had a rifle battalion on the high ground overlooking the dam. German resistance varied from bitter to ineffectual, but the balance of power had fully turned and they could not answer multiple-battalion barrages of U.S. artillery that literally illuminated the valley holding the dam and reservoir.

The message traffic from regiment to army group reflects the tension as the generals awaited word on the condition of the dam and the floodgates, and much of the pressure reached the battalion level at least. The Germans still managed to destroy the flood valves before the Americans reached them. As dawn came on February 10, though, it was clear that the fighting in the Hürtgen Forest was drawing to a close.

Although it was finally in American hands, the Schwammenauel Dam damages caused a slow flooding of the Rur that ultimately delayed Grenade until February 23, when engineers expected most of the water would be drained from the dam’s reservoir.

The Allied logistical situation, coupled with tactical opportunities, had led to the First Army’s September 1944 head-on encounter with the Hürtgen Forest. However, logistics alone did not dictate that

General Hodges keep his troops fighting there. Fairly addressing why the First Army entered the forest to begin with––and the stubborn continuation of operations there––requires understanding of the logistical constraints on the U.S. forces and the context of the operational decisions.

The 12th Army Group’s stunning drive across France and Belgium drew to a stop in mid-September 1944 in large part because supplies were not moved forward at a pace to sustain the maneuver forces. The logistical plan fell apart because it depended on establishing intermediate supply bases across northern France and onward toward Germany. This did not happen because supply, maintenance, and transport units could not move literally millions of tons of supplies fast enough. [Editor’s note: see the Red Ball Express article elsewhere in this issue.]

While conservatism in logistical planning has received due criticism from students of the campaign, the success of Operations Overlord/Neptune was too important to trust anything to chance. It was a necessary trade-off of the available time to plan. It is further doubtful that anyone could have foreseen the collapse of the Heer in Normandy. Even had the planners done so, constraints on trans-Atlantic shipping (if nothing else) would have prevented them from assembling enough transportation resources to support what became the pursuit to the German border.

Tactical/operational opportunities outweighed the supply constraints and the lead elements of the American V and VII Corps drew up to the German border exhausted and short on everything from antifreeze to ammunition.

Based on what Eisenhower and his subordinates knew at the time, the decision to drive through the German border without a thorough logistical pause made sense. However, putting the First Army alongside the British 21st Army Group forced the Americans to confront some of the strongest German border defenses and the Hürtgen-Ardennes region. Unsure of German strength, committed to gaining the Rhine on a broad front, and, based in part on their experiences in World War I’s Meuse-Argonne campaign, Hodges and his colleagues were unwilling to simply bypass the forest. Unfortunately, once operations began there, commanders “had the bear by the tail and we just couldn’t turn loose.” Yet the campaign in the Hürtgen Forest was not the product of a single order. Rather, it was the product of a series of decisions.

Efforts to maintain the momentum of the pursuit were at first logical, but Hodges and his corps commanders did not see the evolving conditions that should have forced them to rethink their operations. They knew full well in September that their own forces were terribly weakened from the pursuit but they persisted in thinking that their enemy was weaker, or at least that penetrating the border defenses would force the Germans to fall back to the Rhine. For their part, the Germans were able to take advantage of the condition of the American maneuver units in September-early

October to stabilize the situation and use their defenses to the best advantage. Only their most senior commanders were aware at the time of plans for the pending Ardennes attack. Even to corps commanders, the forest held no particular value outside of the fact that the Americans were bleeding to death in its midst. Only late in the autumn did the area take on an important role as the northern shoulder of that upcoming offensive.

Barring the discovery of new evidence, it is hard to conclude that the Rur dams were particularly important in the thinking of American commanders before November. Some expressed concern early on about their potential impact, but the dams simply were not stated objectives until December. The only specific objectives mentioned in operations plans and orders were towns and roads. These were important to sustaining an attack across the Rur, but they would mean nothing if forces across the river were trapped by floodwaters.

By the time the Americans launched attacks aimed specifically at the dams, the Germans were also well aware of their importance and they devoted an exceptional amount of artillery and armor reserves to their defense.

When the fighting was over in early February 1945, the casualties had been appalling––probably 35,000 Americans and at least as many Germans fell there to all causes. Many of these losses happened before December, when the Rur dams were finally the objectives of a ground attack. Decisions have consequences, and the irony of this campaign in particular is that it was the product of so many decisions that were generally valid at the time they were made.

The Hürtgen Forest is a relatively compact area, and it is stunning to think of the bloodletting that occurred there. Dispersed operations characterize maneuver combat today; traditional linear operations, when they occur at all, might have 20-mile-deep brigade sectors.

On the other hand, standing on one side of the Germeter-Hürtgen road, it is hard to imagine the intensity of fighting that prevented GIs from crossing only 30 yards to take the buildings on the other side. Other than distant traffic noise, the forest is nearly silent today—only the creaking of the fir branches in the wind; maybe the rustle of a deer—thankfully, nothing more.

Hurtgen Forest goes down with Pelilieu and Operation Market Garden as the three greatest disasters fro the Allies. Two of these could have been avoided completely by passing them around, the other was due to bad intelligence. The Generals at the time made bad decisions and those decisions cost a lot of lives.