By Janis Allen

BACKSTORY: 2nd Lt. Edwin Cottrell served in the U.S. Army Air Forces from August 1942 through 1945, then enlisted in the Air Force Reserves in 1950 and completed 28 years in uniform, retiring as a colonel in the Air Force. His father, Dr. Elmer Cottrell, served in the U.S. Army in World War I, and his father-in-law, Dr. Paul Weed, was wounded and received two Purple Hearts while serving in the U.S. Army in World War I. On April 3, 2020, at age 98, Ed Cottrell told his story:

I was born in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, on January 17, 1922. When I was six months old, my father and mother moved the family to Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania, where my father was a teacher at Slippery Rock Normal School, which later became Slippery Rock Teachers College, which later became Slippery Rock University. I attended elementary school, junior high school, high school, and college in Slippery Rock.

While I was in college, I met my future wife, Millie, while we were freshmen. We went together all through college. After I joined the Air Force, and before I went overseas, we got married.

My military career actually started in the summer of my sophomore year. The government offered any students interested in getting a pilot’s license to enroll in their CPT [College Pilot Training] program, which I did. I went to Sharon, Pennsylvania, and got 30 hours in a Piper Cub. I got my pilot’s license during the summer between my sophomore and junior year.

Pearl Harbor then took place, and, in August 1942, I got my draft notice that said I was going to be called up very shortly. I decided I wanted to be a pilot, so I went to Pittsburgh, 52 miles south of Slippery Rock. I took the Navy test and passed it, and the Army Air Corps test and passed it. The Navy said, “If you join us, you’ll leave tomorrow.” The Army Air Corps said, “We’re not ready for you yet. If you join us, go back to school and we’ll call you.” So, with that being a no-brainer, I decided to go with the Army Air Corps.

I went back to school in the fall of ’42. In February of ’43, I got a notice that I was to report to Miami Beach. I boarded a train in Pittsburgh with maybe 300 to 400 other potential cadets and we arrived in Miami Beach where we did a month of basic training.

From there I was sent to a college in Beloit, Wisconsin, for two more months of sort of basic training—a lot of physical training and radio work. Since I had just about graduated with a degree in physical education, they said, “Why don’t you run our physical training program?” which I did.

When we left Beloit, we were assigned to Santa Ana, California, where there were maybe 30 or 40 squadrons with over 100 people in each squadron. We did lots of drills and lots of PT. I was assigned to flight school at Visalia, California, where I went to train in a PT-19. During that time, they taught us lots of discipline, lots of flying, and lots of marching—PT and marching. During that time, you learned basically what the Army expected of you.

I finished flight school primary training and was then sent to Chico, California—north of Sacramento—for basic. There I flew the Vultee Vibrator, the PT-13, which was really a good airplane to get basic training in. It had wide landing gears and it shook all over, but it was a very reliable plane. From there we started to do aerobatics, and we did a lot of landings and takeoffs on short landing strips. We also did some radio work.

While we were at Chico, we were told to choose the area of the Army Air Corps we wanted to expand our training, whether it be bombers or fighters. So, I chose to go to fighters and was assigned to Luke Field in Phoenix, Arizona, for my advanced training. I flew the AT-6, the “Texan,” which is a great little aircraft still used today as a starter plane for Air Force pilots going into their flight school.

At the end of my training at Luke Field, the last two weeks we had five hours of flying in the P-40 Warhawk fighter. That’s the fighter that we thought we were all going to be assigned to overseas. Upon graduation as a second lieutenant, I went back to Slippery Rock on leave. There, Millie and I got married and spent two weeks together before I was to report to Wendover Field in Utah.

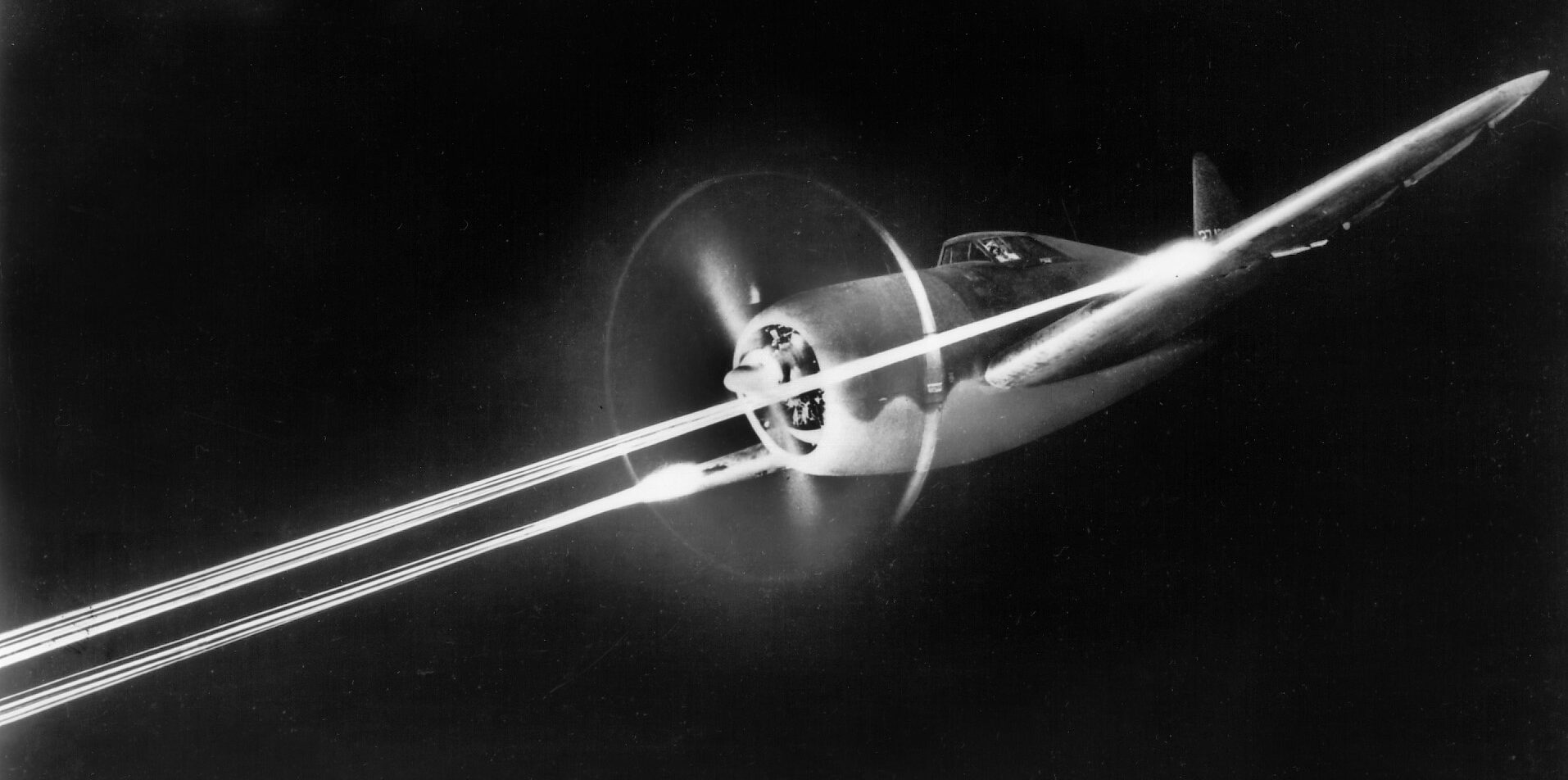

Then I went to Wendover for my indoctrination to the plane I was going to fly overseas. There I found the most beautiful aircraft I’d seen—a brand-new P-47 Thunderbolt, which some people called “the Jug.”

When I saw that P-47, I knew pretty much that we were going to the European theater of operations, where we’d be working with the Army in close support. And that’s exactly what happened. At Wendover, we got a lot of aerial gunnery experience, we did a lot of night flying, we did a lot of formation flying, did a lot of dive-bombing and strafing runs—just as if we were in actual combat.

After six weeks, I was assigned to go to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on the way to New York to embark to Europe. In August 1944, I was put aboard a beautiful cruise ship called the Isle de France, which had been converted into a troop ship. We were assigned two people to a room, which meant that one slept during the day, and one slept at night till we got to England.

We were in England for about a week when, in September 1944, I was assigned to the 48th Fighter Group, 493rd Fighter Squadron, along with a lot of my friends who I trained with at Wendover. We were sent to an airfield called Cambrai, located outside of Paris, where we got our induction to become members of the 493rd. The second day we were there, we were taken up to formation with one of the pilots who was a veteran. We flew formation and did some simulated dive-bombing attacks and strafing attacks without firing guns—just so we got an idea of what we were going to be doing in combat.

While at Cambrai we started to fly our missions and then, in late September, we moved to St. Trond, Belgium. It was a beautiful airfield. There were 10,000-foot runways, and there were three squadrons of the 48th Fighter Group based around the airfield. We were on one side, and the 492nd and the 494th were on the other side. We stayed there from September until the middle of January 1945.

There were three incidents I recall that happened while we were at St. Trond. The first was on December 6, 1944; the weather was very bad. The U.S. Ninth Army was in close pursuit of the German army. We were called on a very rainy, cloudy day with no more than 200 feet visibility, to go skip-bomb a soccer field where the Americans were on one side and the Germans were on the other side. It was pretty much a stalemate.

I flew wing man to our squadron commander, Major Stanley P. Latiolais, that day. He led 12 of us on this mission, where we were no more than 200 feet above the ground, flying at over 300 miles an hour, until we came to the little town of Jülich, Germany. We were required to come in over the American troops, maybe 30 or 40 yards across the field, to skip-bomb the Germans on the other side. We made two or three passes, got a lot of ground fire, and were successful in dropping our bombs. The Americans were able to move forward and push the Germans back.

Upon returning to our base, we found out that almost every plane had a lot of bullet holes in it where the small-arms ground fire had hit the planes. The P-47 was such a good plane that didn’t faze it at all. Our 493rd Fighter Squadron got the Distinguished Unit Citation for that operation. Major Latiolais did a tremendous job of leading us on that mission, where some of the time we were flying on instruments and some of the time actually at treetop level.

On December 17, we were on a mission to locate some German Tiger tanks that were just east of Cologne in a wooded area and were on their way to Bastogne. We found out the Germans had broken through, and the Battle of the Bulge was taking place. Our airfield was the closest to Bastogne, Belgium, during the Battle of the Bulge.

Again, I was flying wing to our commander. We located the Tiger tanks in the woods and went down on a dive-bombing mission. Major Latiolais was the first plane down; I was the second plane down. We dropped our bombs. As we pulled up, we ran into a group of Me 109 German Luftwaffe fighter planes.

On our pullout, on our way up, I noticed an Me 109 coming down at one o’clock toward my squadron commander. I called to him that there was a “bandit” [enemy plane] at one o’clock. The 109 shifted a little bit and the next thing I knew I felt this big blast as a 20mm cannon shell apparently hit my plane. All of a sudden, there was oil all over the windshield and I couldn’t see anything. I was on an upward slope.

I opened the canopy, got on the radio to my commander and said I’d been hit and was heading west and going to fly the plane as far as I could. The plane sort of kicked out but it chugged along at about 120 miles an hour with oil flying out all over my windshield.

I looked out on one side, and there was an Me 109. I looked out on the other side and there was another 109. They crisscrossed behind me, and I thought I was going to be shot down. But they came up and pulled in right next to me. They flew with me back to the bomb line, where they used their thumbs and first fingers to make a little circle and peeled off. That was the signal they were leaving me, “Good luck and God bless,” without shooting me down.

I kept going. I had no idea where I was. My radio still worked. I asked anybody that could hear if they knew where A-92 Field was. A voice on the radio said, “You’re not very far from it. Turn 90 degrees and you should run into it.”

I found out I was south of the airfield. It was strange territory because we had never landed at A-92 before, except when we came in from the north. Just as my plane was ready to touch down at the airfield, the engine froze up. I had to make a dead-stick landing and rolled to a stop.

When I got out of that plane, I kissed the ground because I knew I was a very fortunate person—I could’ve been shot down, the engine could’ve quit—a lot of things could’ve happened. But I came out the best that anyone could have in that situation.

I did lose one of my roommates that day, 2nd Lt. Art Sommers. He was a graduate of the University of Southern California. He got shot down. I didn’t see him go down, but he didn’t come back from the mission. We learned later that they found his plane and he had been killed.

On New Year’s Day, 1945, during the Battle of the Bulge, the Germans had surrounded Bastogne. We were 17 miles away from there. We had been told that if the Germans broke through, we would probably be prisoners of war.

The day before New Year’s Day, we had been told that all but 12 of the planes would be flown out to another airfield; they were going to leave 12 planes with 12 pilots. The 12 pilots were going to be the least-experienced ones. So, on New Year’s Eve, we were told to get rid of all our personal items—burn them and keep only what we needed—our dog tags. No pictures.

We went to bed. At four o’clock in the morning I was told to get up; I was going to be the lead pilot on “runway alert.” Runway alert is nothing more than four planes at the end of the runway, engines running. If the radar picked up any incoming, we were able to take off and go intercept them.

On that day when I was on runway alert, our squadron went on a mission. Another of my best friends and roommates was shot down and killed—2nd Lt. Ted Smith, from Wenatchee, Washington.

Without warning, eight Focke-Wulf 190s came in at ground level, below the radar, and came right over where we were sitting, to the middle of our airfield. There was a B-17 and a B-24 that were burned out, sitting there waiting to be scrapped. The Germans didn’t know that, of course. The Germans hated B-17s and B-24s because those were the planes that were bombing all their cities and factories.

The FW 190s went right to the B-24 and B-17 with their machine guns going. But they didn’t drop their belly tanks. As they came to the end of the field and pulled up to make another pass, our antiaircraft guns hit most of them. Two of them were not hit, and they came around to make another pass. The first of the 190s was on his dive down. He kept going down and down. He didn’t pull out and he crashed at the end of the runway. The other plane kept going and shooting at the B-24 and the B-17.

We went out to where the German pilot was lying with his plane in flames and found out that he had a bullet in the middle of his forehead. He didn’t look to be any more than 17 years old. We found out later that all the American airfields up and down the bomb line were hit at the same time that day. But the German Luftwaffe took a tremendous loss in their raids.

From January 1 on, our biggest concern in any missions that we had was the flak that came from the antiaircraft guns and the small-arms fire from the people that we were dive-bombing and strafing. The German air force, or what was left of it, was primarily used to attack our bombers, which were bombing the factories all over Germany.

The Americans broke through the German encirclement at Bastogne then and finally forced the Germans to retreat. Starting in the middle of January, the Ninth Army, which we supported, was in the north. They started pushing the Germans back. Every mission we flew was in support of the Ninth Army—either dive-bombing or strafing, whatever they needed.

As the Ninth Army moved, we moved from then until May. We took off and landed on metal strips [Marston Mat, or PSP—Pierced Steel Planking] that the engineers put down in farm fields that were level. When we landed, the mud would come up between the metal strips. We had very short runways. When we were ready to move to the next base, the engineers took those metal strips and moved them up to the next area.

We lived in houses right near the airfield, wherever there was anything available for sleeping. They were empty either because people had fled from the Germans, or the Germans had lived in them and had left. A lot of Jewish people were herded away and killed, as you know. There were a lot of empty houses. Some of them had holes in the roofs. Some had no damage. But wherever we could find an empty house, that’s where we bedded down.

We never did establish a [permanent] base from January until May 1945. Then, in May, the 48th was stationed south of Munich. I flew my last mission, my 65th, out of Nuremberg. Then the war was over. The people who had 65 or more missions, if they wanted to, could go home. If not, they would be going with the 48th Fighter Group, which was alerted that they would be going to Japan for the invasion. I chose to go home because I had a little daughter that I hadn’t yet seen.

A couple of my buddies and I came home together; the other pilots left on a boat out of Antwerp to get ready to go to Japan. On their way, the war with Japan ended. I got home on the 1st of July and had time at home before I went to San Antonio to be discharged on July 24, 1945.

Ed Cottrell returned to Pennsylvania to build a civilian career in teaching and coaching: health and physical education, football, basketball, and baseball. He also taught driver training, painted the school buildings, pumped gas, and delivered mail during the summers—anything to support his growing family (he and Millie would have two daughters, Carol, and Susan).

He joined the Air Force Reserves to make a little extra money and still serve his country. When the Air Force Academy was being developed in Colorado Springs, he was assigned to visit local high schools and get kids interested in applying to become cadets. He stayed in the reserves for 28 years, retiring at the grade of lieutenant colonel.

He was the Director of Athletics at Milton Hershey, at an orphan school for boys in Hershey, Pennsylvania. After three years, he went to West Chester State College, where he taught swimming and classroom subjects, and coached tennis, football, baseball, and golf. Eventually, he taught in the graduate school and became the Associate Dean, until retiring at age 57.

About the years after World War II, Cottrell said, “For a long time, I didn’t talk about the war. I wanted to forget it. Then about 15 years ago, at one of our squadron reunions, we talked about how the country was different now.

“So, at that reunion, we all said that if we were ever asked, we would talk about our military experiences. That’s why I talk about what we went through in order to preserve the freedom of this country. If Hitler had been successful, he wouldn’t have stopped at anything. Thank the Lord, we stopped him.”

Ed and Millie lived in Florida and Pinehurst, North Carolina, before moving to Hendersonville, North Carolina. She had worked as a physical education, health, and dancing teacher in many schools over the years, sometimes even with her husband. The couple celebrated their 76th wedding anniversary on April 21, 2020.

This story is from the book “We Shall Come Home Victorious.” Stories of WWII Veterans, by Janis Allen. tinyurl.com/We-Shall-Come-Home-Victorious. Buying this book helps the Veterans History Museum of the Carolinas in its work to honor veterans. Museum admission is free. Visit www.theveteransmuseum.org

Awesome story!