By Steven D. Smith

In the predawn darkness of Dobodura, New Guinea, 2nd Lt. William J. Smith of the U.S. Army Air Corps was roughly awakened by a noncom announcing that it was time to get dressed and get to the mess tent for breakfast.

Smith had not slept well, having spent most of the night fighting mosquitoes that had managed to get inside his cot’s netting. The nervous anticipation of flying another combat mission in the morning did not exactly make for peaceful slumber either. Five days earlier, eight North American B-25D Mitchell medium bombers of the 71st Bomb Squadron, 38th Bomb Group, Fifth Army Air Force had flown north over the Owen Stanley Mountains from their permanent base near Port Moresby to Dobodura, their temporary base of operations. The 38th Bomb Group, known as the “Sun Setters,” was composed of the 71st, 405th, 822nd, and 823rd Squadrons, and 16 other Mitchells from the 38th would join today’s mission. Their target on February, 15, 1944, was Kavieng Township on the northern tip of New Ireland, deep in Japanese-held territory. A long flight lay ahead of the Army aviators, even from this forward airstrip.

At the mess tent Lieutenant Smith sawed into his pancakes and hit a pocket of unmixed batter. As he watched the powder spill down into the syrup, he daydreamed of biscuits with red eye gravy, eggs, bacon, sweet cream, homemade preserves, and all the other delights of his mother’s breakfasts back in Kentucky. As he came back to harsh reality, Smith put sugar in his coffee and then with experienced precision skimmed off the floating ants. Soldiers in South Pacific territories learned that you could not keep ants out of the sugar, and it was just easier to strain them out of your coffee. It was not a great breakfast by stateside standards, but about the best the Army Air Corps personnel could expect in primitive New Guinea.

“Smitty,” as Smith was known to his buddies, made the short walk to the briefing tent with the other pilots and crew members, all of whom keenly appreciated the danger of today’s mission. The briefing officer reminded all that Kavieng would be “target rich” as an extremely important logistical staging base for Japanese installations in New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago. It served as a major supply depot and boasted an excellent harbor, an airfield, and an aircraft assembly facility. Japanese planners knew that if the empire was to maintain any offensive capability in the Southwest Pacific its outposts had to be supplied with replacement fighters and bombers. These aircraft were being assembled at Kavieng to be flown south to Rabaul.

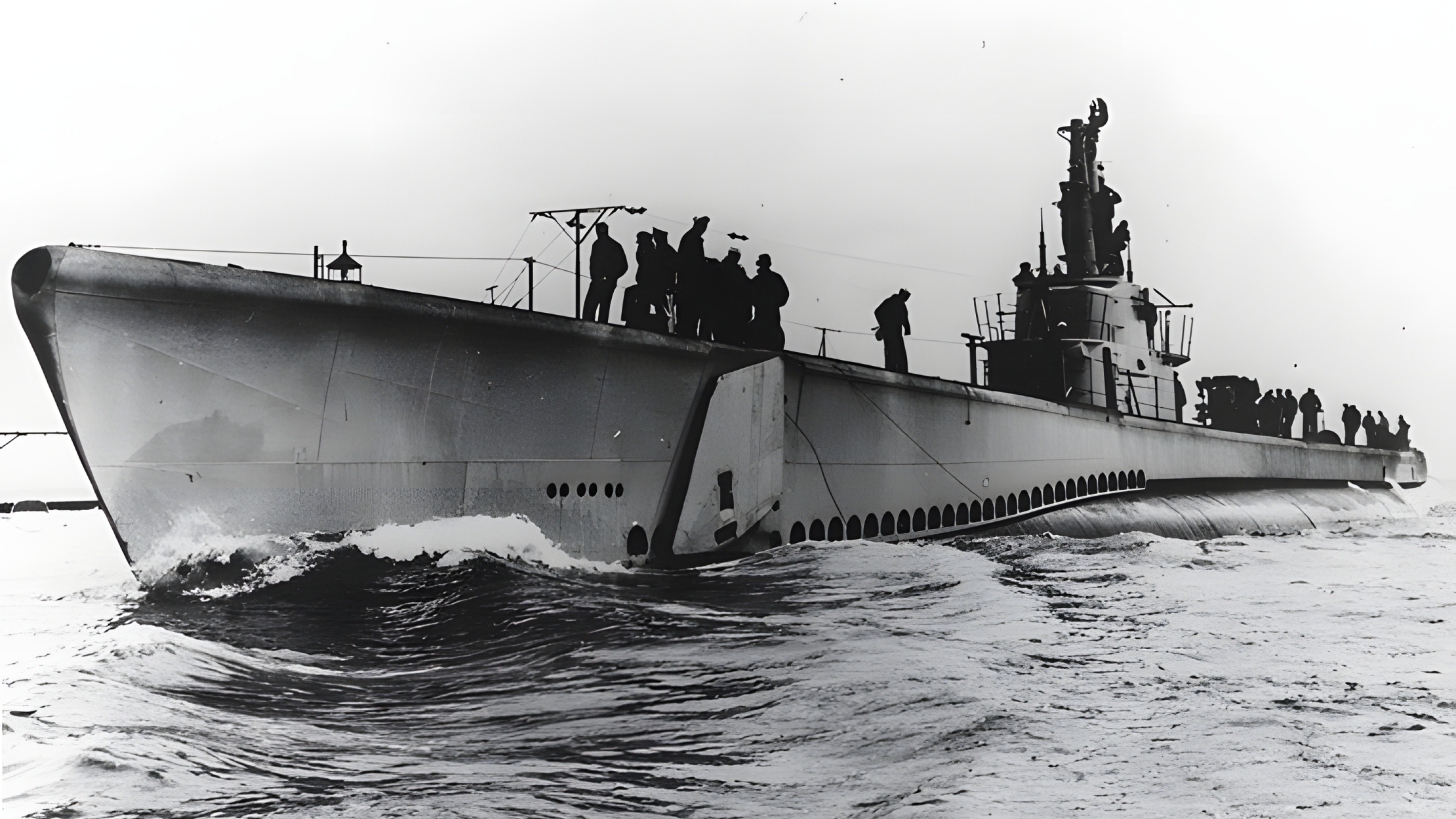

Equally essential supplies, replacement parts, and flight personnel were transported from Kavieng by barges, freighters, and even cargo submarines. General Douglas McArthur and the commander of the Fifth Army Air Force, Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney, were determined to cut off armaments and supplies by executing several intense air raids on Kavieng. This day’s mission would not be the first raid on Kavieng by the Fifth. Consolidated B-24 Liberator high-altitude bomber attacks had been moderately successful in recent days, both in making the Kavieng airstrip a useless patch of bomb craters and in smashing local air power. But Kenney, a superb strategist and leader, knew the need for total neutralization of the target would demand the Fifth Air Force’s signature low-altitude bombing and strafing. The Japanese anticipated these additional low-level raids and meant to employ antiaircraft batteries directed by newly installed radar to defend all approaches to the base. Kavieng’s gunners felt confident that the murderous volume of flak they could deliver in the relatively confined areas of their base would exact a deadly toll in U.S. bombers and flyers.

The crews were informed that if missions like today’s were successful, many of the Japanese bases in New Guinea could then be bypassed without threat of attack from the rear. Rabaul’s huge garrison, over 80,000 men, would be further reduced to an ineffectual corps of castaways, and any shipping in its harbor, absent air cover, would be trapped in port. The once mighty Rabaul military complex would “wither on the vine” and be reduced to a de facto POW camp. The briefing ended with the officer reminding the pilots that fuel preservation was important as the distance to the northern tip of New Ireland would stretch the limits of the range of the bombers. Smith had to admit that the marathon mission today would probably be much more difficult than the 24 previous missions he had survived since arriving in New Guinea the previous year.

Lieutenant Smith walked around the Mitchell B-25D medium bomber to which he had been assigned, number J33F, plane 306 of the 71st Squadron, and closely checked it over before takeoff. He had never flown in this particular plane and wondered whether its nickname, Pissonit, which was emblazoned on the nose, referred to what the bomber was going to do to the enemy or the frustration it had previously given other crews.

Smith admired the firepower the bomber boasted as a result of the now standard modifications made in theater at Brisbane, Australia. The Plexiglas nose of the aircraft had been refitted with four additional forward-firing .50-caliber machine guns. With the two blister pack .50s on each side of the cockpit and the top twin turret facing forward, the B-25D could lay down withering fire on a strafing run. The aircraft could deliver two tons of ordnance and on this mission would carry four 500-pound high explosive bombs. Smith glanced around the airfield and saw it swarming with activity as the other crews made their final preparations. At 7:45 am, the pilots, 1st Lt. Eugene Benson and Smith, taxied to their place in the flight line for takeoff. The airmen heard the R2600-13 Wright radial engines roar and felt their power as the twin engine Mitchell gathered speed and lifted into the brightening Pacific sky.

At Langemak Bay, Finschafen, New Guinea, Navy Lieutenant Nathan Green Gordon of Patrol Squadron 34, Fleet Air Wing 17 was busy making flight preparations for today’s mission. Gordon, who hailed from Morrilton, Arkansas, had flown many missions with the “Black Cats,” a squadron of Consolidated PBY-5 Catalina flying boats painted flat black for stealth purposes in night action. The Dumbo, as the PBY was lovingly called, was a large aircraft: 21 feet high, 63 feet long, with a wingspan of 104 feet. The plane had an incredible range of over 2,500 miles and was employed in multiple roles—executing reconnaissance flights, flying patrol duties, and making nocturnal bombing raids.

Today, however, Gordon was assigned to carry out another facet of the wing’s mission statement. He would fly his PBY, Arkansas Traveler, and orbit off Kavieng, New Ireland, to provide search and rescue cover for a major Army Air Corps bombing mission. Gordon had been briefed that several squadrons of B-25 Mitchell and Douglas A-20 Havoc light bombers would make a strike on the heavily defended base and that planes could go down in surrounding waters.

Gordon ordered the crew to cast off the Cat’s moorings, and he taxied into the bay for takeoff. The PBY was not a particularly handsome aircraft and was slow, with a cruising speed of only 125 miles per hour. Gordon was not concerned about her speed, as he knew she was extremely tough and could reliably perform rescue work even in rough seas. From past patrol and bombing missions, he knew she could absorb a lot of punishment and still make it home. He had all the confidence in the world in the big Cat and in his experienced and close-knit crew of eight: two pilots, a navigator, a radioman, three gunners, and a flight mechanic.

Gordon’s trip to New Ireland was uneventful, but he was grateful for the four Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighters covering him. Japanese fighters, although seen less frequently in recent months, could appear at the most inopportune time. After a long flight to the predetermined position, the Traveler took station well out to sea off the tip of New Ireland and idled at 2,000 feet. Gordon cast a glance down at the ocean, and the reports of 12 to 16 foot seas, trough to crest, were verified. Although the weather was clear and visibility unlimited, he sincerely hoped he would not have to force a landing in those swells.

Eight planes of the 71st Bomb Squadron, nicknamed the Wolf Pack, along with eight other B-25’s of the 405th Green Dragons Squadron and eight Mitchells from the 823rd Terrible Tigers Squadron passed over Sand Island, the rendezvous point for this mission. There they joined elements of all four B-25 squadrons of the 345th Bomb Group, called the Air Apaches, and several squadrons of A-20 Havocs from the 3rd Bomb Group. The formation, designated mission number 46D-1, circled and picked up its fighter escort of Lockheed P-38 Lightings. As Pissonit continued to climb in formation, Benson manned the controls and Smith conversed with Hollie Rushing, the navigator. Farther back in the plane, behind the bomb bay, the radioman, Claude Healan, and the tail gunner, Albert Gross, made ready their stations as the planes cruised toward the target.

As they flew northeast toward Kavieng, Smith mentally reviewed the order of battle for this particular low-altitude raid. The planes of the 71st would come across first, wingtip to wingtip, four at a time, strafing with their machine guns and releasing their explosives. The 500-pound bombs had eight- to 12-second fuses so that the explosions of their own bombs would not damage the B-25s.

The other 38th Bomb Group squadrons would follow the two groups of planes from the Wolf Pack, and the 498th, 499th, 500th, and 501st Squadrons from the Air Apaches would then roar in to continue the pounding. The plane groups would come across in 30-second intervals, and Pissonit was to be in the second foursome of the raid. The formation would approach from the south, and the planes would fly up the New Ireland chain, making a northwesterly run at the base.

The bombers initiated their descent to 100 feet, flying over the township’s coconut palm grove at 270 miles per hour. Benson opened the bomb bay doors, and Smith, adrenaline pumping, checked the readiness of the .50-caliber guns. The pilots of the B-25 would not only fire its guns but also served as the bombardiers, a must on a bombing run at treetop altitude.

At 11:15 am, Smith’s four-plane group started its bombing and strafing attack, and the big .50s let loose a blistering barrage in unison. With four planes abreast a wide bombing swath was assured, and the selection of individual targets was not a necessity. Smith released Pissonit’s payload. The first flight of Mitchells had struck the mark, and dense black smoke already rose from the warehouses at the main wharf. The Japanese return fire was heavy with everything from small arms to 5-inch artillery shells being thrown skyward.

As Benson passed over the target, Smith heard a sharp clap to his left and a simultaneous jolt. Immediately, the left engine burst into flames. Rushing quickly pulled the Lux fire extinguisher, and the fire was chemically suffocated. But then another louder explosion shook the plane as flak hit the fuselage, just forward of where the radioman would be located. The 200-gallon auxiliary gas tank, called a Tokyo tank, which had been installed for extra range, had been ignited and now was a blowtorch with a six-foot plume of flame.

This second explosion had also ruptured the hydraulic lines, causing the landing gear to drop and creating a sudden drop in airspeed. The left landing wheels caught on fire and in turn reignited the left engine. Captain Fred Corning of Seattle, Washington, flying the B-25 immediately to Pissonit’s left, saw the mortally wounded plane streaming flames and thick smoke and gravely mumbled to nobody in particular, “I’ll never see those guys again.”

It was obvious to Smith that the only option now was to ditch the plane in the ocean. But Benson, much to Smith’s amazement, pulled the yoke back and tersely shouted, “We have to gain altitude!” Apparently it was the senior pilot’s desire to put as much distance between them and potential Japanese captors as possible. It was well known to Allied aviators that capture certainly meant brutal interrogation and the horrors of a POW camp, while immediate execution was an equally likely probability. Gaining altitude would perhaps provide a longer glide path for the plane, but Smith realized that the engine fire would soon burn the left wing in two, making Pissonit a spiraling death trap. He barked at Benson that they had to put the aircraft down right away. When Benson ignored him, a struggle ensued as the two pilots briefly wrestled at their respective dual controls for command of the plane. No words were exchanged, and Benson soon relinquished the flying to the junior officer.

Smith’s immediate worry was to ditch safely in the ocean and hopefully get far enough away from the coastline to escape Japanese fire or immediate capture. He gave full power to his right engine and banked to the left, going past Nusa Island just beyond Kavieng harbor. Smith told the crew to brace for a ditched landing and silently wondered if the two men in the rear of the plane were even alive to hear him. Only seconds to touchdown, Smith felt a presence behind him and glanced back quickly toward the bomb bay. He saw tail gunner Gross crawling toward the cockpit over the flaming gas tank. He had been hideously burned.

Smith forced himself to focus on the approaching waves as he cut the right engine and struggled to hold up the nose of the plane. With no hydraulics Smith had no control of the flaps, but providence smiled upon them as the plane slid into a trough instead of slamming into a wall of pitching ocean. The jolt was still tremendous, but the plane stopped upright and for the moment was floating. Burning aviation fuel quickly spread across the water around the wreck.

The most direct avenue of escape from the cockpit was a hatch located over the copilot’s seat, and Benson quickly removed his seat harnesses and leapt up to push open the hatch. He and Rushing hurriedly began to scramble for the exit, literally stepping on Smith as they climbed up and out. Smith looked back again to where he had last seen Gross, but he was nowhere in sight. The Mitchell was quickly flooding, and Smith spun out of his seat to search for Gross. He saw that the entry hatch located on the bottom of the fuselage, just behind the cockpit, had been forced open by the crash. Gross had apparently been thrown forward and down and then was swept or suctioned out into the ocean. Smith could see no sign of him, or Healan, but knew he had but seconds until the plane sank. Only later would he discover that radioman Healan had tried to parachute from the B-25—a fatal attempt at an altitude of 75 feet.

Smith grabbed his parachute and forced it through the escape hatch. He followed it out and stood up on the nose of the plane ready to jump away from it, but burning aviation fuel surrounded the plane. He knew he could dive underwater, but could he stay under until he reached open water? He instinctively looked back at the cockpit as the air forced from the its interior made an eerie moaning sound. Suddenly, an explosion within the plane blew out the Plexiglas nose and lifted him up and fortuitously out over the fiery surface.

Dazed, the 21-year-old aviator came to the surface and winced as his face began stinging in the salty water. Smith angrily noted that his mustache and eyebrows were no longer on his face, singed off by the explosion. Benson and Rushing swam toward him. The three survivors then kicked and paddled away from the plane, fearing further explosions were imminent. Pissonit sank with a bubbly hiss and steamy sizzle as burning metal met the water.

Smith’s parachute provided the group some extra buoyancy and served as something to which the bedraggled aviators could cling to stay together. They all had on their Mae West life jackets, so drowning was not an immediate concern. Taking personal inventory, Smith realized that the front of his left leg from ankle to knee had been raked open by the crash impact. Smith found a tube of lip balm in a pocket and, forcing its entire contents into his hands, made a salve of sorts to spread on his face. Benson was unhurt, and Rushing had minor burns, but like Smith they were understandably shaken. Smith began to assess their situation. They were approximately one mile out from Kavieng without a raft, food, or water and were aimlessly drifting in the shark-infested waters of the Bismarck Sea, and his leg was bleeding. If the tide or currents took them to shore they would be captured, and if they were taken out to sea their prospects of survival were equally bleak.

They could already see that their raid was a major success. Fires raged, and five columns of smoke rose from Kavieng as explosions continued to rock the harbor. Japanese naval and merchant vessels dotted the waters of the harbor, all partially submerged from this and previous raids. The crew could see more U.S. bombers raining additional destruction on the target, but that was little solace as they cast nervous glances toward the beach and made squinting searches skyward for some form of rescue. In a matter of minutes B-25’s flew over the downed U.S. fliers, leading them to wave and shout wildly at possible salvation. Instead of delivering hope, the planes brought them horror when anxious gunners fired on them, apparently thinking they were Japanese sailors who had abandoned one of the ships in the harbor. Efforts to dive below the waves to escape the friendly fire were thwarted by their life jackets, but the gunners’ aim was off, and the .50-caliber rounds fortunately missed. Smith tried hard not to let his rising fear show on his already blistered face.

Unknown to the downed flyers of the Wolf Pack, other U.S. bombers were experiencing life and death struggles of their own. The B-25s of the 345th were in the process of bombing the area of Kavieng called Chinatown, which included the main warehouse facilities and fuel storage areas. The 38th had left these supply dumps a blazing inferno that created billowing clouds of blinding smoke, as Pissonit’s surviving crew could testify. Scores of tires, 55-gallon drums of gasoline, and other Japanese military goods exploded upward among the planes of the 500th Squadron as they roared overhead. These missiles, or perhaps bursting flak, hit the right engine of Jack Rabbit Express flown by Lieutenant Thane Hecox. The plane suddenly veered to the right and downward, crashing in a fireball at the edge of Chinatown. All aboard were killed, including Captain Sylvester A. Hoffman, who was on his last mission before returning to the States.

The operations officer for the 500th, Captain William J. Cavoli, led a group of three B-25s just to the right of Hecox’s flight. He and co-pilot 2nd Lt. George H. Braun flew a B-25 that bore no nickname, identified only by the serial number 41-30531. As they flew into the maelstrom, Cavoli was forced to rely on his instruments because of the dense smoke. As his plane was enveloped by the blackness, it was rocked by a direct hit to the right engine. The engine exploded in flames, and aviation fuel spread the fire over the wing and down the length of the right side of the fuselage.

As the B-25 returned to daylight the crew was slammed by suffocating heat as pieces of the engine nacelle and wing melted and fell away. As the ground rushed up toward them, Cavoli and Braun struggled at the controls to keep the dying plane airborne until they could reach the ocean. They managed to dodge palms, cleared the beach, and only 600 yards from the shoreline they ditched, nose up. The Mitchell initially skipped lightly off the water, but on the next contact the aircraft gouged to a grinding halt in a huge column of spray. The B-25’s nose was partially torn away, and the incoming sea rushed in with such force that the material was torn from the navigator’s pants legs. Braun jettisoned the life raft, and the two pilots gathered and rescued the other crew from the wreckage. Incredibly, all six men aboard had survived, although some suffered deep cuts and one a severely broken arm. After the emergency kits were retrieved, they paddled furiously to escape the sinking plane.

At Chinatown the fires burned ever higher, but the punishment by the Fifth Air Force continued. Major Chester Coltharp, squadron commander, led the 498th over the target in Princess Pat, a B-25 sporting the falcon head nose art adopted by the squadron. The planes dropped 59 additional 500-pound bombs. More than a dozen Japanese floatplanes anchored at the shore were shredded, a large wharf was destroyed, and a 2,000-ton freighter was sunk. Debris continued to be launched by the surface explosions, and some U.S. planes, in an effort to avoid this danger, pulled up, slowing their B-25’s and presenting easy targets to the angry Japanese gunners below.

Gremlin’s Holiday, flown by 1st Lt. Edgar R. Cavin, was one such plane. Inside the top turret of the plane sat Staff Sergeant David B. McCready, who fired away with his twin .50s at Japanese sailors on the deck of a submarine below. Japanese incendiary shells suddenly opened up the bottom of the fuselage and ignited the auxiliary gas tank. The resulting explosion shot the turret dome up and away, and McCready instantly lost his helmet, headset, and goggles in the slipstream. The force of the wind scoured the sergeant’s head and face while simultaneously the fire below threatened to burn his lower body. The gunner desperately backed down out of his compromised position and painfully scrambled forward toward the radio compartment.

Captain Robert G. Huff, the squadron adjutant and tent mate of Major Coltharp, was an unauthorized passenger on Gremlin’s Holiday. As a ground officer he had always wanted to witness combat and had convinced Cavin to let him come along. After feeling the concussion of the explosion, he instantly wished he had stayed at Dobodura. Cavin realized the fire that McCready had sought to escape was spreading and intensifying. Huff and Staff Sergeant Lawrence Herbst tried in vain to extinguish the blaze. After observing the advancing fire himself, 2nd Lt. Elmer “Jeb” Kirkland, the co-pilot, warned Cavin they had to immediately ditch Gremlin’s Holiday.

In the radio compartment Technical Sergeant Fred Arnett gently held the burned McCready in his arms and braced for the impact of the imminent crash. The plane stalled and went in nose first, going under the waves and then surging back to the surface like a porpoise. The pilots and Herbst escaped via the cockpit hatch, while Huff had to swim underwater to use the same exit. McCready and Arnett had been knocked briefly unconscious by the crash but regained their senses quickly with the horrible realization they were underwater. After some desperate struggles with straps, belts, and underwater wreckage they exited the hole ripped out of the bottom of the aircraft and with lungs bursting popped to the surface.

The crew had all survived the crash, but not without serious injuries. Huff was wounded with three broken lumbar bones and a deep gash to his leg, while Arnett had suffered a broken shoulder and a slash down his face that exposed teeth and bare cheekbone. McCready was in terrible pain with a compound fracture of the right ankle, a deep gash to his hipbone, and severely burned arms and hands. Soon other planes of the squadron circled and dropped survival kits and bright yellow rafts to their brethren swimming below.

At 11 am, 24-year-old Nathan Gordon received the first confirmation that his day was indeed going to be very busy. Even from his distant vantage point the rising columns of smoke over Kavieng were easily seen. The radio traffic provided the news of crashed planes, ditched aircraft, and crews in the water. The first call for Gardenia Six, his call sign, came from an Army-based radio at Cape Gloucester, New Britain, that relayed a message from a returning B-25 that multiple aircraft were down. But by that time Lieutenant Gordon was already approaching the township looking for rafts, wreckage, or any sign of survivors in the water.

Gordon suddenly noticed the telltale yellow-orange dye that downed aviators used to mark their positions. As he took the big Catalina down for a closer look he spotted oil on the water and decided to pick up anybody he might locate. He realized that the ocean landing he was about to make would be more difficult than any he had ever attempted. If anything, the wind had picked up and the height of the waves had grown.

It was essential that Gordon set Arkansas Traveler down with the bow high and the stern touching the surface first. This method of landing employed water resistance to slow the speed of the Cat and improve the accuracy and safety of the touchdown. But successfully pulling off this maneuver would be much more difficult because of the necessity of landing on the down slope of the big swells to avoid plowing into a wall of seawater. Regardless of Gordon’s training and actual experience, the first landing was rough. Upon the hard impact the 16-year-old Catalina popped several rivets in the hull. The plane started taking on water through the rivet holes. Fortunately, the damage was not serious, and Arkansas Traveler taxied quickly toward the dye. As they slowly moved through the debris field of a crash they saw an object and believed it was an aviator, but as they drew near they saw it was a partially deflated Army Air Corps raft. There were no survivors to be found. Gordon sadly shook his head and opened the throttle, running through the dye still in the water. It was frustrating to know that this was one crew he could not rescue.

As the Traveler gained altitude it was spotted by Captain Tony Chiappe, the operations officer of the 498th, flying above in his Mitchell, Old Baldy. Chiappe had left Major Coltharp to circle Cavin’s crew and discourage Japanese attempts at capture while he searched for the PBY. Although radio problems kept Chiappe and Gordon from directly talking, hand signals and relays through the P-47s got the message across that the Catalina should follow his B-25. Gordon quickly flew the short distance and dropped two smoke flares to mark the location of Gremlin Holiday’s survivors: five crew members and one stowaway.

Gordon made a much better landing this time and taxied toward two rafts that had been tied together. Standard rescue procedure called for the plane to be stationary and let the lighter object, in this case the rafts, come to the plane. However, this was certainly not a standard rescue as the shells falling from the Japanese shore batteries reminded everyone. The crew threw a heaving line to the water-soaked aviators, which they caught on the first attempt. But the forward motion of the plane with its props still turning was too great. It might actually drown the men clinging to the rope. Gordon ordered the line cut and realized that he would have to kill the engines. He did not want to drown the people he was seeking to save; nor did he want the heavy seas to lift weakened men into the still turning props. As Japanese fire bracketed the big Cat, Gordon’s mind raced ahead, imagining their horrible condition if the engines did not start.

Gordon taxied back to the wide-eyed men in the water. Ensign Jack Kelley was sent to the port blister, where the waterlogged survivors would be taken aboard. Paul Germeau, the strongest man on board, was waiting there to pull them into the Catalina. Cavin’s men caught another line, and Gordon’s props slowed and then stopped altogether. Japanese machine-gun fire sprayed the water nearby. Only the lifting and pitching of the plane in the high seas confounded the aim of the Japanese gunners. The crew of Gremlin’s Holiday was hard to wrestle aboard. The men were helpless dead weight and were difficult to grip as they were coated in the oil from their downed aircraft. Huff and McCready were especially tough to handle with their severe injuries. One by one, they wriggled, rolled, and were manhandled aboard. Cavin, the last of his group, fell through the blister window, and the rafts were cast off.

The shells fell closer now, and Gordon knew that the Japanese artillery would soon zero in if they did not quickly get back in the air. The pilot pushed the starter buttons, and with a belch of black smoke the engines came to life. Slapping the waves as she gathered speed, the plane rose off into the smoke-filled skies of Kavieng.

It had now been over two hours since Smith, Benson, and Rushing had gone into the water. The yellow-orange dye from the stain canisters rigged to their Mae West’s had long since dissipated. The dye was designed not only to give visibility to rescuers, but also was thought to serve as a shark repellent. The high swells provided a good vantage point when the survivors were carried to the crest, but upon sliding down into a trough there was no visibility at all. From time to time they had cast anxious glances down in the clear water, mistaking shadows for sharks.

Suddenly, the three heard planes approaching. Were they friend or foe, and if they were friends would they fire on them again? Straining their eyes as they looked into the mid-day tropical sun, Smith realized that they were indeed good guys, huge P-47 Thunderbolt fighters. Quickly they took the chrome mirrors attached to their life vests and flashed them toward the fighter planes overhead. Their hearts leaped as the P-47s dove toward them and began to run a tight circle around their position, this time with no ill intent. It was obvious they were now found, but their rescue still seemed highly improbable.

The Traveler followed the P-47s’ directions to the three bobbing figures on the water. Gordon was too close to Kavieng, and the enemy had duly noted his presence. As he moved toward the water and a third landing, he did so through a hail of tracers. The crew had taken pencils and inserted them into the sprung rivet holes, intentionally breaking them off in an effort to plug the leaks. The old Cat certainly did not need any new holes caused by enemy munitions. Traveler’s buoyant bow eased down a mound of seawater, and the plane settled on a surface whipped into froth by wind, waves, and Japanese shells.

Once again the props were killed, and the crew watched as Germeau coaxed the heaving line under the wing toward the men in the water. The rocking ocean banged the three against the side of the hull, but they came in quickly, sliding roughly over the blister window’s coating. Smith joined the increasingly cramped group inside. Again, the PBY’s engines reliably sprang to life.

Traveler lurched forward, and in her wake geysers rose from Japanese gunfire. Gordon knew that a few more seconds on the rescue scene would have spelled disaster for the plane and its occupants. The tough old bird groaned with all the extra weight but proudly left the sea again. As he lay back against the plane’s bulkhead, Smith allowed the desperate hope of survival to transform into a sweet reality.

The P-47s had to depart, as their remaining fuel would barely get them home. Gordon followed their path and had already put 10 miles between burning Kavieng and Traveler. Once again the now familiar voice of Major Coltharp crackled over the PBY’s radio and announced that the major had spotted another ditched B-25 only 600 yards off the beach. Gordon did not want to accept what he was hearing, and he began to calculate the mounting odds against surviving another rescue attempt. Nathan Gordon’s character did not, however, allow the option to cut and run become viable. He realized he could not leave any Americans to the mercy of the Japanese.

In the rear of the PBY, Smith immediately noticed Traveler was executing a gradual wide turn back toward Kavieng. He squeezed his eyes tightly shut and grimaced because he knew they must be headed back for another rescue attempt. The anguished thought that Gordon was absolutely crazy to put them all in such great peril was immediately erased with his guilty realization that Gordon had taken the same risk to pick up Pissonit’s survivors.

With Princess Pat flying cover, Arkansas Traveler circled Captain Cavoli’s crew in Kavieng harbor. Nate Gordon flew right over amazed Japanese gunners temporarily stunned into inaction. He made his best landing of the day, a good thing considering the plane’s compromised bow plates, coming to a stop within a few yards of the rafts. Immediately, the Catalina became a duck in a shooting gallery as the shoreline lit up with muzzle flashes. The fire was so intense that Gordon was sorely tempted to push the throttles forward and simply take off again. Shells landed all about the plane, and he could attribute their current safety only to the Almighty’s protection. In record time six more passengers were hauled aboard as the fear of getting killed by enemy fire overcame pain and fatigue.

The starboard engine immediately restarted, but the portside engine refused to turn over. The plane was now running in a circle with Japanese shells getting ever closer. Gordon knocked the hands of Ensign Walter L. Patrick, his co-pilot, away from the starter button. It was evident to Gordon that one of the engines was flooded. They waited for a couple of minutes, which to every occupant on board seemed more like several hours. Patrick finally engaged the starter again, and the prop blades started moving, slowly at first, then picked up speed until finally the blade tips were a blur. Again, with a payload grossly beyond the norm, Gordon, his other seven crewmembers, and 15 Army aviators left the heaving ocean in the faithful Arkansas Traveler.

Coltharp, coming alongside, waggled his B-25’s wings in acknowledgment of Gordon’s skill and bravery. Coltharp was magnificent on this day as well. He had remained over the target searching for survivors and flying cover until it was doubtful his plane had the fuel left to get home. Indeed, the Princess Pat would have to make an emergency landing at Cape Gloucester with only 10 gallons of gas in her tanks. Major Chester Coltharp later received the Distinguished Service Cross.

Four times Gordon had put his plane down on the rough waters of the Bismarck Sea under heavy Japanese fire and had survived. He was relieved to be heading back to the safety of Allied-controlled skies and to Finschafen. Now out of harm’s way, the crew of Traveler began to realize the enormity of what they had done. They had executed perhaps the finest air/sea rescue of the Pacific War and had in all likelihood saved the lives of 15 men. Strangely, as Traveler reached cruising altitude, those rescued and many of the crew, including Gordon, felt lightheaded and jittery, and some could not even light cigarettes because their hands were trembling. Gordon would soon have the satisfaction of delivering his cargo of aviators back to the naval hospital and safety.

With a total of 23 men on board, Traveler was fully packed. Lieutenant Smith felt a mixture of pain, relief, grief, exhaustion, wonderment, and deep gratitude. Looking around at his fellow rescued flyers, Smith broadly smiled as he recognized a face he had not seen in some time. Lieutenant Jed Kirkland, co-pilot of Gremlin’s Holiday, met Smith’s gaze at the same time, and they both laughed. Maneuvering toward each other, they embraced and talked excitedly. Lieutenants Smith and Kirkland had become fast friends at flight school in Columbia, South Carolina, but were not even aware that they were in the same theater of action. But in war, even the joy of a miraculous rescue often is fleeting. Kirkland was killed in action six weeks later.

Mission 46D-1 was a complete success. Reconnaissance photos revealed total devastation; the supply dumps and warehouse area at Kavieng burned for several days, and smoke was visible for 70 miles. The success came at a high price: two B-25s from the 38th, three from the 345th, and three Grim Reaper A-20s. Kavieng and its facilities were completely destroyed, and the base would remain meaningless for the remainder of the war. The capabilities of the Japanese at Rabaul were further nullified, and the invasion of the Admiralty Islands could be carried out.

Navy medical corpsmen at Finschafen quickly but carefully evacuated the badly wounded. Smith, against his protests, was made to stay overnight in the Navy hospital for treatment of his burns and his leg wound. A Navy Seabee introduced Smith to the delights of the cafeteria the following morning. There he enjoyed the best food he had tasted since his training days in Australia, and the first ice cream he had eaten in many months. Before noon, the 71st Squadron commander flew over in a fat cat, a Mitchell stripped of armament and used for transport only, and ferried Pissonit’s crew back to the Seventeen Mile airbase. As they returned Smith had a profound regret that he had not had the opportunity to personally thank that brave pilot of the PBY for rescuing him. He had attempted to do so but had been told that Gordon had already left for another mission.

Square-jawed, blond-haired Nathan Gordon, whose courage, strength, skill, and iron will were well demonstrated by the multiple rescues made that day, was presented America’s highest military decoration, the Medal of Honor. He was indeed the only PBY pilot given this award in World War II and the first Navy man in the Southwest Pacific to receive the award.

Admiral William F. Bull Halsey stated, “Please express my admiration to that saga writing Cat crew. This rescue was truly one of the most remarkable feats of the war.” Gordon would survive the war and return to his native Arkansas, ultimately serving as lieutenant governor of his beloved state for 20 consecutive years. He practiced law until he died at the age of 92 in September 2008.

William J. Smith flew 46 more combat missions over New Guinea, the Dutch East Indies, Biak, Morotai, and the Philippines. He survived both “the best landing I ever made” while a 100-pound parafrag bomb was hung up in his bomb bay, and having a piece of shrapnel go through his plane’s windshield just over his head. He was promoted to captain before his 23rd birthday and became the 71st Squadron Operations Officer.

General Kenney personally awarded Smith the Purple Heart, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Air Medal. After the war Smith graduated from Marshall University and from Southern Theological Seminary and became a Baptist minister in 1950. He served for more than 50 years in pastorates in Kentucky, Alabama, Louisiana, and Georgia.

At long last, in 1999, Reverend Smith was able to express his gratitude to Nathan Gordon by phone. This “thank you” call developed into a long and satisfying discussion of wartime experiences and crossed paths in the South Pacific more than half a century earlier. After retirement, and for more than 20 years, Smith served as a volunteer chaplain to hundreds of U.S. Army basic trainees at Fort Benning, Georgia. In March 2002, Smith was able to fly in a B-25J nicknamed Panchito at the invitation of its owner, Mr. Larry Kelley, for the first time in 57 years, and in fact on his 80th birthday!

Bill Smith was hesitant to talk about wartime experiences but did often say that he learned one very important lesson from Navy pilot Nathan Gordon that day: never give up on rescuing anyone. Captain William J. Smith, a veteran of 72 wartime missions, died on December 23, 2010, three months before his 89th birthday. On his bedside table were his well-worn Bible and a mahogany model of his beloved B-25.

Hi Guys…

My name is Daniel McCready, That was my Dad on Gremlins holiday. Dad is gone now and he didn’t talk much about what he went through. I hope there is someone that can give me more details or direct me to other sources of info.

It would be greatly appreciated.

Daniel, i’m mac rushing. my dad was with smith and benson on the second wave of 4 abreast b25’s that had to crash when one of their engines was hit. i know a few things, mainly because of benson. he used to visit dad and they got to talking when they drank. my dad never talked either. i would be happy to tell you what i know.

This is very interesting. My Uncle Gavis McCall is the pilot in the painting above of the B25 Near Miss. with the Falcons. I was looking for information about his group.

What an absolutely amazing story. This site is wonderful

My father, John Taylor Young Jr., was a co-pilot/pilot of a b-25 in the 38th bomb group, 71st squadron.

I would like to find any records information on his years of service/missions flown. Could anyone provide information on where to start? I’ve been to this website: https://www.sunsetters38bg.com/ and found these 2 pictures:

https://www.sunsetters38bg.com/index.php/gallery/image?view=image&format=raw&type=orig&id=152

and

https://www.sunsetters38bg.com/index.php/gallery/image?view=image&format=raw&type=orig&id=153

I believe these are from flight school so I am not sure if he flew with this crew in combat, they are: William Richardson (pilot), Paul Jonson (tail gunner), Jack Collum (flight engineer/top turret), Bob Garmoe (Radio Operator/Waist Gunner), Lt. John T. Young (co-pilot), Lt. Bob Sherrard (Bombadier-Navigator)

Any Advice would be appreciated. Barry Young [email protected] 602-743-2826