Interview by Allyn R. Vannoy

An estimated 1.2 million people were employed by the German ground-based air-defense system by the end of the war in Europe. In April 1945, 44 percent of those serving with the flak arm were either civilians or auxiliaries, including factory workers, prisoners of war, foreign nationals, and high-school students.

At 16, Gunther Vogel was a member of the Luftwaffe’s air-defense forces, a gunner assigned to an 88-mm anti-aircraft gun. His life would take a number of twists and turns, both during and after the war. Before the war ended, he would be working for the British Army. Years after the war, he would have a chance encounter with the family of the pilot of the first aircraft he disabled.

What’s the story behind your journey to being born in Germany?

My mother and father met at a newspaper office in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in the twenties. With my mother pregnant, they took a ship to England, their favorite country, for me to be born there. But there were great storms in the Bay of Biscay and, with her almost giving birth, they got off in Cherbourg and traveled to Berlin, where I was born on June 17, 1928.

Where did you live in Germany?

Berlin-Charlottenburg [a district in the heart of the city], then from 1939 till 1943 at the Potsdam Institute as a cadet at a military college.

Did you have any brothers or sisters?

A half-sister and two half-brothers and a full sister, Ruth Judith, whose Jewish-sounding name made my parents subject of Nazi Party attention. My father, Papito, disarmed the suspicions by becoming a member of the Party, which also allowed him to work in Germany without hindrance.

Were you a member of the Hitler Youth?

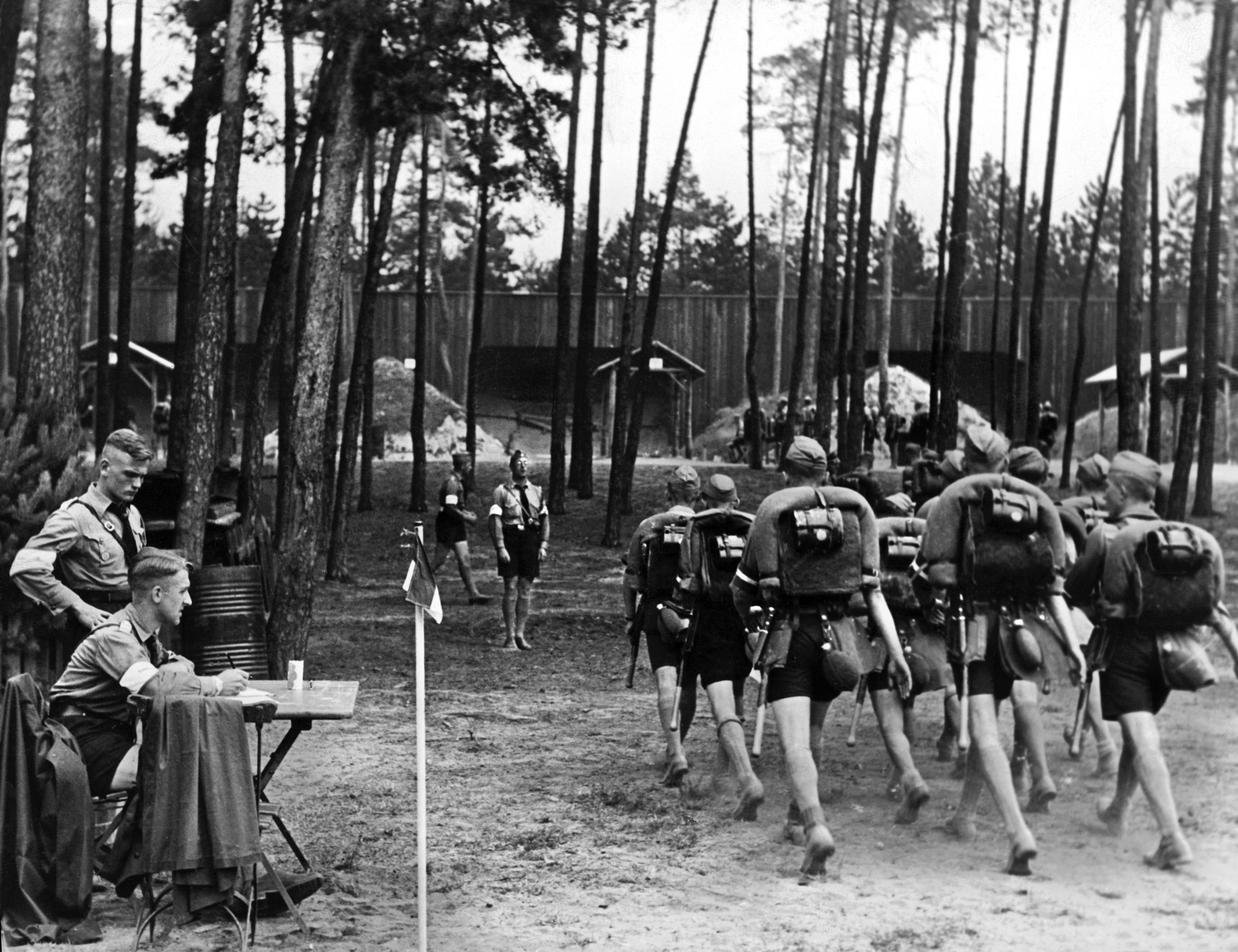

Every German [male] child had to join the Hitler Youth at age 10, girls later. We had duty every Thursday afternoon, and our duties were much aligned with those of the international Boy Scouts. There were no acts of cruelty, and political influence was minimal—other than wearing a swastika on the black/brown uniforms that we wore on that day. Singing while marching was our best-liked activity. Until 14, we were known as the Young Folk. A change in duties and activities did not happen until we were known as the Hitler Youth, but that was spared me by way of college.

It was said that my father spoke nine languages, which is probably the reason that he spent most years away as a German government representative of agriculture and industries. English was my first love in middle school, and, by age 14, I had devoured T.E. Lawrence [of Arabia] and his The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, with some wonderment that Germans were the bad guys [in it].

In stage plays, l was always a British officer, naturally on the losing side. My favorite teacher had taught German in London and “Cockney speak” became my favorite communication with him. Our exchange students were from Britain and Finland. We grieved over every [Luftwaffe] bombing raid on people we had great admiration for. Thus, the bombing of Coventry [November 14-15, 1940] was a sad day for us.

I understand that your father’s death was somewhat of a mystery. Can you say what were the circumstances?

That is something wrapped in secrecy. It was 1943. We [the family] were summoned to a huge farewell parade. We were never told how and under what circumstances he died. But the last address was, by coincidence, a place known as being a concentration camp just outside Berlin. I forget what the name was. [It was Sachsenhausen, in the northern Berlin suburb of Oranienburg.] They said he did not die in the concentration camp, but in a hospital adjacent to it. So that is all we knew. We were not allowed to view an open casket. I was just a kid and didn’t even know what it meant.

When did you join the Luftwaffe?

After the death of my father in 1943, his brother, Helmut, was listening to my complaints of overly strict discipline of the military life at the Potsdam Institute. He found a similar, but much more likable, college in the occupied area of Poland, where I was accepted in late 1943.

In February 1944, there was a visit from a Luftwaffe recruiter with orders to enlist all 15- and 16-year-olds. Most of us were shipped off to the state of Schleswig-Holstein, in the northernmost part of Germany, and to a boot camp of the Luftwaffe, where I was trained as gunner on a 20mm light anti-aircraft gun.

How were you selected for the 20mm gun crew?

Because I was a good shot with a .22 rifle. That was a helluva a recommendation.

How long was your training?

We were conscripted in February 1944. Graduation was, by sheer coincidence, on D-Day [June 6, 1944], which we kids were not aware of, as we were busy setting up our 1937 model 20mm cannon in Neugraben-Fischbek, in the Elbe River area south of Blankenese [near Hamburg].

What units did you serve with?

We kids were never told the numbers or designations of the units we served in. Flak auxiliaries were drawn from high schools and then split up according to specialties—radar, communications, or weapons. My specialty was gunner on a 20mm model 1937, and as such I was subject to being assigned to different batteries of 88s. Boot camp was named Büsum, in the state of Schleswig-Holstein.

You were reassigned from a 20mm anti-aircraft unit to an 88mm AA unit?

Yes. In August 1944. We hit and damaged a P-51 Mustang.

How did that happen?

That happened on August 4, 1944. I was stationed in Hamburg during some big attacks, but a 20mm gun [fires] only so far. They decided that we were better used to protect an airfield near Hannover … so we were moved near the village of Barrl.

We arrived there August 2. On the 4th, we were playing around on the gun, pretending to be shooting at planes. We had all those training planes—German Focke-Wulfs. We would take aim at the training planes, as they landed, as targets, yelling “tac-tac-tac,” mimicking the sound of a gun shooting.

There were five of us. I was sitting in the chair of the gun doing the play thing of shooting at ghost planes, when, suddenly, there was gunfire and an explosion. It was only a second and a half, and my buddy helped me turn the gun and I just fired at the sound of an aircraft coming in from three o’clock [to the east]. All the training planes took off and landed to the west, nine o’clock. This Mustang came from three o’clock and flew over a little woods adjacent to our gun.

I was able to turn the gun and follow him as he disappeared at nine o’clock, directly over us. He had his machine guns blazing—the rounds stitched the sand, like in a movie, to the left and right of us. Nobody got hit. I noticed that one of my rounds took off a piece of wing on the right-hand side of the plane. Then he zoomed up—he wasn’t shot down—and took off and disappeared.

The commandant of the airfield later congratulated us, and we were told we had shot him down. We [the gun crew] were promoted to other anti-aircraft batteries. After a short home leave, we were given orders and rail tickets to report to various Luftwaffe batteries nationwide. Mine was located in what then was called the Polish Protectorate near Odertal-Blechhammer in Upper Silesia. But no light AA gun was available. So, I was re-trained as a lateral gunner on an 88.

The location of the AA gun was at a village called Mecnica, not far from the only still-functioning refineries in the Blechhammer district.

[The Blechhammer area was the location of German chemical plants, POW camps, and forced-labor camps, not far from Kattowitz and Breslau (now Wroclaw, Poland). The Blechhammer synthetic-oil production facility began operations on April 1, 1944. In June 1944, the U.S. Army Air Forces considered Blechhammer one of the four principal synthetic-oil plants in Germany, and the U.S. Fifteenth Air Force, operating from southern Italy, dropped 7,082 tons of bombs on Blechhammer.]

At the beginning of the Soviet surge in January/February 1945, l was issued a Skoda double-barrel machine gun, 1918 vintage, packed for 25 years in the wooden crate and still stinking of industrial oils. It took me a week to figure out that two barrels demanded at least three hands. Those were provided by a gray-haired lieutenant, formerly a major in the 1915 Austrian army.

We fought side-by-side during the long nights in February 1945 until all youngsters were withdrawn by unexpected orders from Hermann Göring when it became known that the Soviets executed all under-age enemies found with weapons as not covered by the Geneva Convention—something known as franc tireur [a civilian sniper or partisan]. I had four months left to become “of age.”

Do you recall any other specific actions or events while with your unit?

I was on duty with an 88mm flak unit during an American raid on the industrial area on August 22, 1944. As the combined dozens of batteries of 88s, 105s, and 128s along the [bomber] route from Italy defended the approaches, a B-24 crashed near our battery. We young guys all volunteered, and I was allowed to participate in the honor salute to the fallen U.S. airmen on August 24.

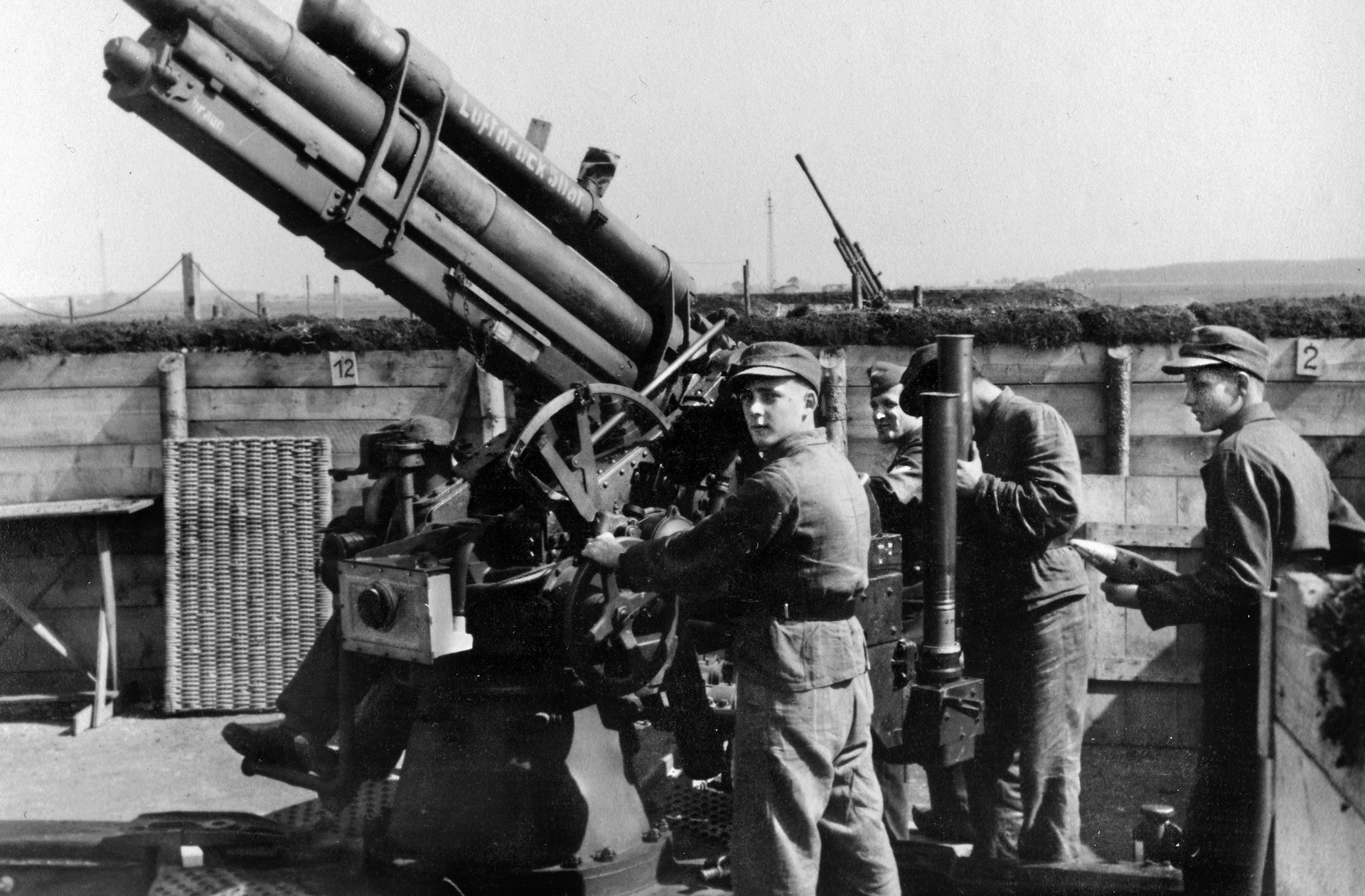

You mentioned being a “lateral gunner” on an 88. What is that?

I never found the actual term, but that’s one who turns the gun in a lateral manner by hand. The 88 is a big gun, very heavy. I was 16 then, so I had a hard time turning the damn thing. It’s the side gunner, turning it in the horizontal, side-by-side with another gunner who operated the gun in the vertical. He was usually a big, burly fellow; I was not a big, burly fellow. I could not have managed that. There was no machinery to help. When I turned that gun, it was like turning the world. That’s how hard it was.

I was designated Gunner Number Two, and I think he [the vertical gunner] was Gunner Number Three, Gunner Number One being the loader. Direction came from the command post. You had a large dial, like a clock, which provided the commands to you. You had to respond to a little hand on the dial that moved from number to number that corresponded to the horizontal directions. I had to follow the command as it came and counter the command on my end. In other words, I had to follow an indicator that was at eye level, turning left and right. We called it, “to cover the numbers.”

How many people were there on an 88mm gun crew?

Eleven. One or two of them were trusted prisoners of war, Soviet soldiers. Having been taken in the Ukraine, many were anti-communists and so were employed as “Hiwi’s,” [Hilfswillige], meaning “willing to help.” [Non-German Luftwaffe volunteers included Walloons, Croats, and Russian POWs, who served as ammunition carriers and loaders.]

They were trusted with ammo. Usually, on every large gun, we had at least one of them. They were given some freedom; they were trusted, but of course they knew if Germany lost the war they would be sent back [to Russia] and executed as traitors.

The 88 had a high rate of fire, keeping the crew very busy, right?

They said it was one every 10 seconds. But I am not quite sure for the simple reason that after the first shot you were deaf. It was also very smoky [this from the propellant used in the ammunition], but this stopped after a while. We were told that it was special ammo. They had scientifically figured out how to prevent much of the smoke coming out of the barrel [smokeless powder]. We did not have masks. We also did not have gear to protect the ears.

The 88s were deployed in batteries. How many guns in a battery?

I don’t know if we had six or nine guns. We might have even had twelve. I was on “Dora Two.” Each of the guns had names. They were always arranged in a circle, so we were protected from enemy fire or raids from all directions. But the main direction of our gun was between three and six o’clock [given the battery’s layout], raids coming from the south. I think the first attacks from Italy started in July of ’44; I did not get to the battery until August. By then we were regularly being raided, probably at least once a week.

Could you actually see the bomber formations?

They came in fairly high. But we were not privy to seeing them because our eyes were on the dials, indicators [directional instruments]. Our eyes were nailed to that. So, you couldn’t look up to find where they were coming from. Most of the attacks came from the south. And then we followed them.

We were at the foot of a mountain range [the Sudeten Mountains, on the Czech-German border]. Blechhammer was a death trap for American bombers because there were literally hundreds of guns, dozens and dozens of batteries along that whole range. Usually, when they approached, like little silver arrows on the horizon, is how they came. We knew they were not coming for us; we were probably about three or four miles from the target. They never bombed us.

As members of the gun crew, did you feel you were making a difference?

No, that never came up. At that age you have a Boy Scout attitude. It’s for your own good. Because you get a good education. To many of us it was a lark. Until the first grenade [mortar shell fragment] hits you. Which happened after the American bombers stopped coming and the Russians hit us with mortar fire.

American raids stopped on December 28. That’s when we were told that they, the American air forces, didn’t want to risk the Russians being bombed. So, on the 28th of December 1944, all the attacks stopped, and that’s when we were attacked by Russians who had come in over the night, killing the four German observers; we then knew our ground war with the Russians had started.

So, you were close to the approaching Russian Army?

Absolutely. They occupied a village, a church belfry that had been occupied by a panzer unit with forward observers. The Russians eliminated a guard of four and then directed mortar fire on our position. One round landed right over me when I was bending down to pull a box of hand grenades. I was bending down while standing in the mud, to pull the box to my position where I was defending with a machine gun. Just as I stood back up, a round exploded on the berm above me. I got hit by a piece of mortar shell on the rim of my helmet. I didn’t even know that I was hit.

The day after the church incident, I had gone to the village where I had been persuaded to help a German-Polish widow—her husband had been killed at Stalingrad—with her chores between my guard and gun duties. As I came near the house, there were groups of black-uniformed German tank crews getting a stub-nosed gun vehicle aimed at a two-story house.

Shots came out of two of the cellar windows, but the windows were too low for the vehicle’s gun. Two of the tankers managed to creep close and, using their hand grenades, silenced the rifle fire.

I was dressed in my basic Luftwaffe gray uniform—no belt, side arm or steel helmet, obviously off duty. An officer ordered me to creep through a jagged hole that used to be a side entrance to the basement. It was obvious that a grown man with equipment would not have cleared the broken beams.

I didn’t know if l had more to fear from that tank commander or some still-alive Russian shooter, but a quick glance showed nobody alive. As l came back to the mangled wooden staircase, l stepped on a man’s arm, covered with watches to above his gray, ashen elbow.

Seconds later, in hysterics, l raced across the street till l was caught by a tank guy who managed to get me to tell him that l had only seen one body.

You were still assigned to the anti-aircraft unit?

Oh yes, we were with the anti-aircraft throughout. We could have been taken over by ground forces, but there weren’t any to go around. There was only one small panzer group that had advanced into our area, near the border with Poland, to ward off the Russians after they had taken Breslau. When they took Breslau, we knew our days were numbered.

Was your unit withdrawn?

The night before the big Russian attack—we didn’t know that at the time, we youngsters, everybody who was a Luftwaffe auxiliary, high schoolers—we were all withdrawn without being given the reasons. They put us on a big panzer, a tank, that carried a whole bunch of us to the rear in the middle of the night. It was the oddest thing. We were all withdrawn, and only our elders remained behind. I turned my double-barreled Skoda machine gun over to a sergeant. We were told to mount a Tiger tank that was waiting. We were driven [while sitting] on the top of the tank.

The Russians found out about it and peppered us with machine-gun fire, but there were no casualties. We reported to a little village west of Mecnica, two or three kilometers away. There we stayed the night. The next day we were picked up by trucks and later marched. We ended up near Prague, to be demobilized. I think that sometime in February of ’45, we were sent home.

Why were you demobilized?

We had been conscripted; everyone who was a full 15 years of age by the middle of the year—that means in June. I should not have been conscripted because my birthday is June 17. It was found out that we had been inducted illegally because we were not the proper age to be soldiers. So, we were demobilized with orders in our hands to report to the military office in our home town on our 17th birthday, and I was not yet seventeen. None of us were seventeen.

So, that’s why they withdrew us, and also because of the Russians. Stalin had passed an edict that anybody who was not of soldier’s age would be executed. They had taken whole groups of us, auxiliaries, who were caught on the ground by the Russians as they advanced, and they were executed forthwith.

So Hitler, for some reason, was advised by somebody that children should not be put in danger. That was the reason given to my battery and my buddies and buddies from other batteries that took part in the exodus. The railhead to send us back from the Russian Front was near Prague—a place called Brüx, now called Most. That’s where we were demobilized, with orders to report on our 17th birthday, which would have been June 17, 1945. By then, I was in the British army.

What happened to your family during the war?

They were bombed out by the RAF in Berlin, two years in a row, but were able to find places to live out of harm’s way. The RAF bombed our house in 1942 with incendiaries, and in September of ’43 they used the big bombs, “Blockbusters,” I think we called them. And that’s when we lost our house again. The first time the Nazi Party repaired it in a week, gave us new furniture. We were made whole after the first attack.

In the second attack in September of ’43, we were the only house in Charlottenburg, a rich borough of Berlin, the only house in the neighborhood that got hit. It was completely destroyed.

It took me about a month after being demobilized to find my family. I went from one place to another that I knew of, and finally found them with the help of the Red Cross. When I went to Hamburg, they [the government] were so well organized that when I mentioned the name, they opened the book at the “V’s” and found me in 20 seconds, and then found my family.

I went to the village where they were supposed to live and found that they lived in a chicken coop on a farm. It was a nice chicken coop, as far as chickens are concerned—and for people who don’t have a place to stay.

How did you end up working for the British?

One morning—I remember that it was the 20th of April, because that was Hitler’s birthday—the Brits rolled in with half-tracks and trucks and not a steel helmet in sight—it was impressive. The mass of people suddenly rolling down the country road into the village was something to see. They were all smiling, and they were throwing things from the trucks and throwing things into our front yard.

My mother was very anxious that they were poisoned. She came out screaming—I had four little brothers and sisters. Everybody was running out there, picking up packages with strange writing on it. They all said “Cadbury.” Of course, Cadbury is the biggest British candy maker. When we found out that it wasn’t poison, we felt comfortable with being occupied. It was such a change, psychologically, to suddenly know that the war seemed to be over. But the war was still going on—it was April 1945.

The following day an officer in a jeep came to inspect the house on the farm. We met him at the door. As he left—I don’t know what possessed me—I ran after him, stood at attention, clicked my heels, and said to him, in my best English, “Is there anything I can do for you, sir?”

He turned around and grabbed me and swung me around as his corporal, the jeep driver, who had a Sten gun and he [looked like he] was going to shoot somebody. The officer put me down and said to the driver, the first English words I had heard, “You blithering idiot, stop it!” [Gunther had studied English for three years and had also learned Spanish at home from his parents.]

He then put me down and asked if I would like to work for them. I was speechless. I said, “Work for you? What does that mean?” He replied, “You will join us. And travel with us as an interpreter.” And that’s what I did. There were still two weeks to go in the war.

They asked me if I had any connection with a foreign country that was not at war with the Allies. I said, “Yes, my mother was Argentine.” A company tailor made an epaulet [for my jacket] that said, “Republic of Argentina.” I then helped procure food for the Brits and billets because they were living in tents.

I stayed with them for a couple of years. I was paid. I lived in the castle where the Royal Armoured Corps (RAC) had its headquarters, in Belsen. At the time, I didn’t know that Belsen was such a devilish place. The castle was beautiful, from old German nobility. Living in the castle with the Royal Armoured Corps, I never suffered any shortages.

So when you hear about how the poor Germans were treated and lived because there was nothing—there was no food, there was no water—there was just no life for those people, I never felt anything of it. I didn’t get starved. I got fed because I had British food. When I went on leave, once a month, to where my family lived, I was able to take food and cigarettes that they could use to barter with farmers. So, my family lived okay because of my job.

Later, I stayed with the Lancashire Regiment, a unit of the REME, Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers. Then l was ordered to report to the headquarters of the Royal Armoured Corps at Bredebeck Castle near Bergen. Not until l arrived there did l hear of Belsen and its connotation.

(Bergen-Belsen, or Belsen, was a Nazi concentration camp in northern Germany, southwest of the town of Bergen. Originally established as a prisoner-of-war camp, in 1943 parts of it became a concentration camp. Initially, this was an “exchange camp,” where Jewish hostages were held with the intention of exchanging them for German prisoners-of-war held overseas. The camp was later expanded to accommodate Jews from other concentration camps. After 1945, a displaced persons (DP) camp was set up nearby. From 1941 to 1945, almost 20,000 Soviet POWs and a further 50,000 inmates died there.)

What were some of your duties?

My commanding officer was a Major Goldsmith. My job was liaison with the German staff working for the British officers who came from different units of the British occupation forces. I had a room upstairs in the headquarters looking out over a reflection pool in the center of the drive area of the main entrance.

I accompanied British officers and officials to find billets for the arriving troops, and I later attended court hearings in disputes between occupiers and, ironically, women impregnated by soldiers of the occupying forces.

In my spare time, on weekends, l served as barkeeper and learned all about some of the officers’ predilections. They came from many different units, including the tank corps.

When did you emigrate from Germany?

That was on Christmas Day 1947, with exit papers issued by my commanding officer in Belsen in recognition of my services to the occupation forces. We—my sister, Judy, and I—took a train from our village to Hamburg to catch The International—a train from Copenhagen to Paris or Amsterdam. We went to Holland.

Germans were not allowed to leave Germany, but my mother had married again—he was American, and he allowed us to emigrate to Holland. We stayed there, my sister and I, in Amsterdam, for a couple of weeks until a ship arrived to take refugees from Europe. Arriving in Hamburg, it took DPs to South America and places in between.

We were, I guess, the only Germans on board. We went from Amsterdam to Hamburg and, ironically, my aunt—my mother’s sister—and her husband were aboard. She was born in Chile and worked as the Chilean proconsul, and she was allowed to go on that refugee ship with her husband, but not in the hold [steerage] with the other poor European refugees, but in First Class. My sister and I were in the hold, down below. We made it to Argentina in February 1948 and stayed for 10 years.

[My family] arrived in the United States in September 1958, in Miami from Buenos Aires. Now married, with two little children, I went from Miami to Los Angeles, where I worked for 20 years as an architectural designer; I designed offices. Later, I visited Oregon, looked around, and liked it. I retired in 1977 and moved to Oregon.

Epilogue

Some 12 years ago, Gunther came across an article in the local newspaper in Oregon that told of a Lieutenant Roland Strong, of the USAAF 505th Fighter Squadron, a Mustang fighter pilot who had been shot down over Germany, on August 4, 1944. In his post-war memoirs, Strong described his P-51 being hit by enemy fire in the right wing and the engine while flying a mission near Hamburg, Germany, and that he was able to fly for about 80 miles before the engine gave out, just short of the North Sea coast. Strong was able to bail out, was captured, and spent the rest of the war as a POW.

Incredibly, Gunther discovered that Roland Strong lived in nearby Bandon, Oregon. He was able to get a phone number for the Strong family and decided to call, but with some trepidation. Gunther said, “When I called them, how do you approach somebody on the phone and say, ‘I shot down one of your family members. Can you tell me about him?’ How do you handle that? I fought with myself. How could I possibly approach that family and tell them about their loved one? Because I thought he was dead.”

Referring to the newspaper article, the woman who answered his call said that she was not only the editor of the newspaper, but also the daughter-in-law of Roland Strong. She told Gunther that Roland Strong had made it home after the war, had married and raised a family, and that he had worked as a longshoreman in Coos Bay, Oregon.

He had died in 1992 at the age of 74.

She said that they knew he was shot down over Germany, but they didn’t know any of the details. He had three sons and they all lived nearby. Gunther later found out that he had even worked with one of the sons. They invited Gunther to a family gathering and allowed him to read Roland’s personal papers—notes he had written while in the POW camp.

Gunther said, “For years I had been wondering if I would ever find out what happened to the plane and the pilot we shot down. What a relief that Roland got away and was not lost to his family.”

Today, at age 93, Gunther Vogel lives a quiet life in Langlois, on the Oregon coast.

Allyn R. Vannoy is the co-author of ‘Against the Panzers: United States Infantry vs. German Tanks, 1944-1945: A History of Eight Battles Told Through Diaries, Unit Histories, and Interviews’. He lives in Oregon.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments