By Phil Scearce

Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber crews of the U.S. 11th Bombardment Group spent the first three months of 1943 organizing on Hawaiian airfields and flying practice and patrol missions around the islands. By mid-April, with no strike missions and no contact with the enemy, the bomber crews were restless. But the morning of April 17 had a different feel—electric.

The group’s officers were still in a closed-door briefing while rumors buzzed about a bombing mission, their first. All that remained for pilots to tell their crews was when and where. When pilot Lieutenant Joe Deasy met with his crew and gave them the particulars, it was the first time they had heard of Funafuti. Twenty-three Liberators would fly to Canton Island, a pork-chop shaped atoll 1,900 miles southwest of Oahu, refuel, and continue 740 miles farther to Funafuti in the Ellice Islands group, more than 2,600 miles from Hawaii.

“We didn’t know where Funafuti was,” B-24 gunner Sergeant Ed Hess recalled. “When we saw the map, we griped about it being halfway to Australia.”

Airfield at Funafuti

Six months before, on October 2, 1942, 11 ships of the United States Navy entered Funafuti’s lagoon and landed a Navy construction battalion. The Seabees immediately began construction of an airfield and support facilities while Marines prepared defenses and set up antiaircraft guns. To build the runway, the Seabees bulldozed thousands of coconut trees and covered arable land with hard-packed coral. The airfield was completed before the end of the year.

On the long flight to Canton, the men ate sandwiches delivered to the flight line from Kahuku’s mess hall. They used their flak jackets for pillows and stole naps in the back of the airplane. A relief tube, or “piss pipe” as crewmen called it, was built into the side of the plane just aft of the left waist window; another one was installed behind the flight deck. There was a portable toilet that most men avoided, better to wait than use the “honey bucket” and have to wash it out after landing because “if you used it, it was yours to clean,” radio operator Sergeant Herman Scearce remembered. Even the piss pipe could be a nasty problem at higher altitudes where its flow could freeze and cause a messy backup.

The Navy garrison on Canton treated its overnight guests well. The Air Corps men ate a hot meal in the Navy mess hall and slept in clean barracks with fresh bed linens. Early the next morning, 23 refueled B-24 Liberators took flight for the final leg of the trip to Funafuti, and on the afternoon of April 18 the wisps of land of the Ellice Islands came into view.

The planes approached Funafuti’s coral airstrip from the southwest. The island, shaped like a long, narrow boomerang, curved from the southwest to its thickest part in the middle, then bent back toward the northwest. Long and graceful, Funafuti was about 50 yards wide at each end, about 700 yards wide in the middle, and seven and a half miles long. Waves broke along the eastern side, the dark blue water of the Pacific just beyond and to the right as the aircraft approached.

To the left of the island, in the middle of the boomerang, was a lagoon, its calm water a beautiful shade of light blue fading to green close to shore. Coconut trees covered the island from its lower tip, nearest the approaching planes, and ended at the airfield. The white coral runway cut straight across the leading edge of the boomerang, beginning just a few feet from the ocean, and it seemed to end in the ocean on the other side.

After landing, the aircraft were parked along the runway side by side. There were no taxiways and very few revetments or bomb proofs on Funafuti to shelter parked aircraft, though there were plans to add them later. If a plane was hit during a Japanese air raid, the planes on either side were also at risk. But the airmen on Funafuti were not worried about a Japanese attack because Funafuti was just a staging base; they were not going to keep the planes there long. Besides, the briefing officer back at Kahuku made it clear that the Japanese would not know they were there.

Dogpatch Express

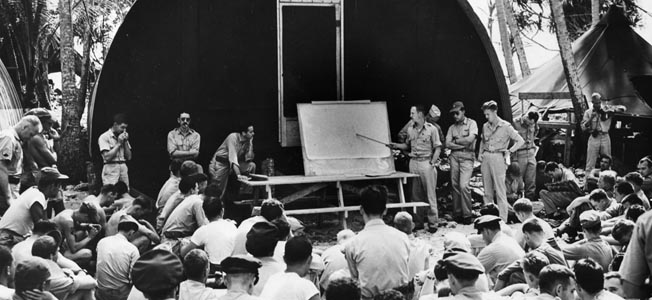

Early on Monday, April 19, 1943, an officer stepped front and center on Funafuti’s outdoor stage before the assembled air crews. The men sat on felled palm logs arranged in rows like seats in a theater. Behind the officer was a map, and on the bottom right of the map was Funafuti. There was another island near the upper left corner, and beside the map was a separate, large, scale drawing of the second island, Nauru.

The officer tapped his pointer on targets and visual references on the map of Nauru. He described antiaircraft gun positions and what kind of fighter interception the men would face. When he was finished, a weather officer took the stage, describing the conditions expected through each part of the flight. Next, the operations officer gave the crews critical mission details, including engine start time and order of take off. Each man mentally calculated when he needed to be at the plane in order to preflight his equipment and be ready for engine start.

After the briefing, aircrews prepared their planes for the next day’s mission. Ground crews fueled each B-24 with 2,700 gallons of gas from tank trailers towed behind Cletracs, tracked vehicles similar to bulldozers. Flight Engineer Jack Yankus and Assistant Engineer Bob Lipe confirmed the fuel level and checked engine oil levels of their B-24, Dogpatch Express. Yankus, Lipe, radioman Herman Scearce, and gunners Hess, Elmer Johnson, and Al Marston cleaned and oiled the barrels of their machine guns and loaded them with ammunition, belts of .50-caliber rounds in a repeating sequence of two armor piercing, two incendiary, and one tracer. Scearce confirmed the radios were working properly and ready to go.

Bombardier Lieutenant Shorty Schroeder oversaw the bomb loading of Dogpatch Express. Eight 500-pound general purpose bombs were loaded in the plane’s bomb bay racks from bomb trailers pulled by a truck. Most of the bombs were fused to explode on impact; some were equipped with delay fuses. Once the plane was loaded, Yankus checked the landing gear for four inches of travel in their shock-absorbing struts because less could cause the gear to fail.

Taking Off Toward Nauru

After a fitful few hours of sleep, the crew of Dogpatch Express walked to their plane. Yankus made certain the ignition switches were off, then he and Lipe pulled the propellers through, counting six propellers at each engine, two full revolutions of the Liberator’s three-bladed prop. While Scearce rechecked his radio equipment, Yankus climbed aboard and fitted the pilot and copilot parachutes into the recesses of their seats, then reported to Lieutenant Joe Deasy that the plane was ready.

On the flight deck of Dogpatch Express, Deasy and copilot Lieutenant Sam Catanzarite completed their preflight checklist as pilots and copilots aboard 22 more Liberators on Funafuti’s moonlit runway completed their own. At engine start, four 14-cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-1830-43 radial engines, 1,200-horsepower each, joined the motors of the other aircraft to produce a mighty harmony unlike anything Funafuti had ever heard before.

Before his takeoff roll, Deasy opened the throttles and held the brakes until engine manifold pressures reached 25 inches of mercury. When Deasy released the brakes, Catanzarite held the throttles to the stops so they would not creep back. Yankus called out speed as Dogpatch Express accelerated, slowly at first with its full bomb load. Deasy began to apply gentle pressure, pulling the yoke back, and the heavy bomber lifted off Funafuti’s dusty coral runway.

In the predawn darkness of April 20, the B-24s took off, each loaded with 4,000 pounds of bombs. One plane developed an engine problem and turned back to Funafuti, but the remaining bombers droned on toward a midday strike against Japanese positions on Nauru.

Nauru lies 26 miles below the equator, 1,000 miles northwest of Funafuti. Oval shaped with about eight square miles of territory, it is ringed by trees and a sandy beach on its perimeter. The interior of the island is almost solid high-grade rock phosphate, essential in metal alloys and used in bomb production. Phosphate mining, refining, and shipping facilities operated by the British on Nauru before the war were shelled by a German auxiliary cruiser in 1940 and seized by the Japanese in 1942. Far flung Nauru, with the unusual distinction of being occupied by the British and attacked by both German and Japanese forces already during the war, was about to be bombed by Americans.

“Man Your Guns”

The Liberators drew closer to Nauru and more than 220 air crew and observers were wholly and irrevocably committed. There was no way to avoid whatever was to come, no place to hide. Nauru lay just beyond the horizon, the distance closing at more than three miles per minute. The American bombers would reach their target at noon, each man keenly aware that the bright, beautiful day meant Nauru’s Japanese defenders would see the bombers approach with plenty of time to prepare their reception.

Scearce recalls sitting at his radio operator’s table behind copilot Catanzarite when navigator Lieutenant Art Boone leaned toward their pilot and said, “Joe, we’re one hour out.” Scearce glanced at his pilot, and from the right and behind him, he saw Lieutenant Joe Deasy swallow and take a breath before speaking to the crew through the interphone. “We’re 60 minutes from the target, boys. Man your guns.”

Scearce and Yankus unplugged their interphone headsets and moved toward the rear as they had practiced a hundred times before. They stepped into the bomb bay, Dogpatch Express’s four massive radial engines howling in unison, much louder than they had seemed from the flight deck. Moving along the narrow catwalk and indifferent to the thousands of pounds of high explosives just inches to their right and left, waist gunners Scearce and Yankus gripped the framework of the bomb racks as they went. The vibrating metal felt cool.

After Scearce and Yankus passed, Bob Lipe took his position in the top turret, just behind the flight deck, and rotated the turret clockwise, then back, out of habit. Ed Hess settled into the nose turret. Elmer Johnson, already in the aircraft’s rear section with Al Marston, stepped back from the piss pipe and stretched himself before jacking up the belly turret with the hand pump, just enough to release its safety hooks. Johnson opened a hydraulic valve and allowed the turret to slide into the wind stream beneath the plane. He glanced back at Scearce and Yankus, smiled, and made a diving motion, hands together as if he was on the high board at the YMCA, and then opened the turret’s hatch door, stepped into the turret, and folded himself into position.

Marston moved up the sloping floor toward the twin .50s in the bomber’s tail. There was an interphone jack box at every position, and each gunner plugged in, pulled on his interphone headset, and checked the jack box to make sure the switch was set to “INTER.”

Throat microphones around their necks, Yankus and Scearce glanced down and pushed their flak jackets flat with shuffling feet, standing on them for protection against gunfire from below. They pushed their wind deflectors out, swung open their windows and latched them overhead. Already Lipe, Hess, and Johnson had reported ready. Yankus and Scearce swung their machine guns into the air stream and charged their guns with an expert pull on the handle.

“Right waist gun ready,” Scearce said. “Left waist ready,” Yankus reported, then Marston called in from the rear. Joe Deasy recalled telling his crew, “Keep your eyes open, keep the chatter down, and call ‘em when you see ‘em. Hold your fire ‘til they’re in range.”

Zeros Attack

Hess swept the nose turret side to side. Lipe kept the top turret forward, mostly, rotating through 360 degrees, first right, then to the left, as often as his stomach could handle it. Al Marston shifted his eyes up and then straight behind the plane, scanning the sky from just below the twin rudders of his bomber, wind whistling to either side. Elmer Johnson rode below the plane, almost in his own world, the expanse of the ocean thousands of feet below. Scearce searched the sky, and behind him Yankus gripped his machine gun. Back to back they shared almost identical views, a beautiful bright sky, sun directly overhead, other B-24s nearby.

Deasy’s voice broke the interphone silence, clear and steady, “Eleven o’clock, got two coming in 11 o’clock high!” Scearce heard Lipe and Hess open fire from the top and front of Dogpatch Express. He and Yankus leaned forward, trying to see, fists gripping their guns, instinctively pointed where the men were looking.

“Two o’clock high, coming down fast, be ready, top.” Lieutenant Deasy’s voice was matter-of-fact, Yankus remembered, almost calming, though the words came quickly. The top turret opened up again. The first two Japanese planes, attacking head-on, had broken off to one side of Dogpatch Express. The Liberators had been modified by the Hickam Air Depot with tail turrets mounted in the nose, surprising the Japanese fighter pilots who expected to attack the weak, glass nose of unmodified D model Liberators. After their initial head-on pass, the Mitsubishi Zero fighters attacked from other angles.

Scearce’s heart pounded like a jackhammer. He could not see the Zeros yet. The nearest B-24’s top turret and left waist gunner blazed away, their tracers leading Scearce’s eyes above Dogpatch Express’s right wing, when a blur of gray flashed beneath the wing. Scearce reacted instantly, pushing his gun barrel low, squeezing the trigger. A two-second burst and the Zero was gone before Scearce heard its 14-cylinder Nakajima Sakae 12 engine scream past. Elmer Johnson in the belly turret then saw the Zero and squeezed off a burst.

Up top, Lipe spoke clearly, a nervous edge in his voice. “One, two more at two o’clock high … out of the sun again!”

“Eight o’clock low, coming up! Another one at five o’clock,” Yankus and then Johnson called. Each man was part of a whole, a working team, and part of their machine. Dogpatch Express was now fully engaged, every gun hammering at the attacking fighters in turn. The .50-caliber machine guns pounded like angry fists beating hard and fast on a steel door. Hot, spent brass and gun belt links falling to the floor clinked like glass breaking around the waist gunner’s feet.

“We were all scared,” Scearce recalls. “We all prayed selfish prayers…God, just get me back on the ground again.”

“This is a Long Way From Gunnery School”

Scearce joined Johnson and Lipe, five .50-caliber machine guns blazing at a single Zero fighter, tracers spitting toward the Japanese plane in burning white lines. Lipe, in the top turret, sent a stream of gunfire into the belly of the Zero as it streaked overhead. From the left waist window, Jack Yankus saw Lipe’s tracers drill the unprotected bottom of the enemy plane. He watched it pitch forward, nose down, and lost sight of it as it plummeted straight down. A few seconds of strained quiet followed while the men scanned the sky.

Scearce suddenly spotted a Zero “four o’clock high” and called out the position. Lipe swung around in his electrically powered turret. Scearce bent low, aiming high, waiting for the range to be right when Lipe opened up. Johnson swung left and strained to see the Zero. Scearce saw muzzle flashes through the Zero’s propeller; its twin guns seemed to be shooting straight at him. Squeezing the trigger, Scearce swung his gun down as the Zero passed. He saw tracers run through the Zero’s cowling and remembered that a .50-caliber bullet could knock a cylinder head off a Zero’s engine.

Nose gunner Ed Hess gave a quick burst from up front, swinging through 10, then nine o’clock as the fighter passed, and then it was quiet again. Scearce kicked some brass away from his feet, took a deep breath, and thought, “This is a long way from gunnery school.”

As the Zeros moved off, the crew was sure the other bombers were catching hell behind them. The twin 7.7mm machine guns of the Zero fighters were supplemented by menacing 20mm cannon mounted in each wing. The explosive round from the 20mm gun weighed more than a quarter of a pound, and hits by the Zero’s cannon could be devastating.

However, the Zero’s impressive armament belied the nimble fighter’s weaknesses. The Japanese plane sacrificed the added weight of self-sealing fuel tanks and armor protection in favor of speed and agility, qualities that could serve the Zero well in combat with other fighters. As an interceptor of B-24 Liberators, however, with their armor protection, self-sealing fuel tanks, and 10 .50-caliber guns, the Zero was vulnerable, even fragile. Zero pilots pressing home an attack against a Liberator needed nerves of steel.

Dogpatch Express Bombing Run

Aboard Dogpatch Express, bombardier Lieutenant Shorty Schroeder was ready to take control of the plane for the bomb run, his bomb sight connected to the flight controls. The bombardier aimed his entire aircraft through the bomb sight.

The Japanese fighter pilots changed tactics as the bombers readied for their bomb runs, and the flak batteries on the ground below began sending their shells skyward. Nine Zeros circled at a distance, chasing one another’s tails in an oval, a racetrack pattern that advanced as the bombers sped forward. The Zeros fired their guns each time the circuit brought them to face the American bombers, but with his own plane’s right wing and engines between him and the enemy fighters Scearce could only watch, a white flash each time, a blink, and hope the streams of Japanese bullets missed.

Antiaircraft gunners now took their turn. Flak bursts filled the sky ahead, inky dark puffs drifting closer as the bombers approached. In the distance, a single Japanese plane idled along, out of range of the Liberators’ guns, holding the same altitude as the American planes, reporting it to the ground batteries below. The B-24s rushed unalterably, purposefully ahead.

There was no dodging the flak. Dogpatch Express held 7,500 feet altitude during the bomb run, level, steady, with no deviation from course. This was a bomber at its most vulnerable during a strike mission, 45 seconds that lasted forever, 45 seconds, it seemed, before the crew could breathe again. Flak bursts, like sinister potholes in the sky, caused the plane to shake and bounce as they exploded. Scearce was amazed anything flew through it. Spent flak pelted the plane like hail on a tin roof.

“We wanted to be small, very small,” Deasy remembered. They wanted the bomb run to end, the bombs to be away, but they also wanted the bombs to be on target. They did not want their trip to be wasted, did not want to have to do it again. Scearce noticed his knuckles, ghost white on the grips, and he forced himself to flex his hands as he watched the sky.

“Bombs Away!”

Behind the flight deck of Dogpatch Express there suddenly was a loud thump and a metallic clang, followed immediately by an evil hissing sound behind copilot Sam Catanzarite. Scearce heard navigator Art Boone say, “We’re hit!”

“Bombs away!” Schroeder reported, as the last 500-pound bomb fell from its rack. The plane seemed to leap in the air, free of its heavy burden. Deasy pushed the control yoke forward, nosing Dogpatch Express over, and put the throttles to the stops, getting the hell out of there fast.

The hissing slowed as Yankus traced the damage. Sunlight streamed through a hole just below the leading edge of the right wing. A piece of flak, a jagged shard of twisted metal three inches across, had come through the ship just behind Bob Lipe’s legs as he sat in the top turret. After cutting a compressed oxygen line, the bomb fragment had stabbed through the pilot’s seat. The Zeros harassed the trailing B-24s for half an hour more and finally turned away.

“How’d we do?” Deasy asked. There was a pause, a moment’s hesitation, before Yankus spoke. “Everything hit the water, sir.” Scearce had seen the splashes, too.

Scearce and Yankus swung their guns inside, locked the windows closed, and pulled the wind deflectors in tight to the sides of the plane. Bob Lipe stepped down from his turret, wiped his face on his sleeve, and looked up at the ugly hole in his plane’s skin. He hadn’t heard the impact. A few feet aft, and the flak might have hit the top turret. Ed Hess unfolded himself from the nose. Yankus steadied Johnson as he pulled himself from the belly turret and helped him jack it up and secure the turret inside the plane. Johnson stood and stretched, as he had before settling into the turret almost two hours before.

From the rear, they heard Marston say, “Fellas, I’m going to sit here a minute, watch our ass a little while.”

A Lonesome Return

Out of danger, the aircraft returned to a higher cruising altitude and continued toward Funafuti. Their targets, phosphate plants, gun positions, maintenance and barracks buildings, and runways on tiny Nauru, were so small that each plane had to make its bomb run alone. As a result, their return to Funafuti was staggered.

Since each plane had to find its own way, each crew needed a skilled navigator. There was nothing below but ocean, no point of reference except the sun. Navigators relied on dead reckoning, calculating position based on the previous position, taking into account time, heading, and drift. Errors in dead reckoning were cumulative, so each calculation increased the difference between the aircraft’s plotted position and its actual location. Because the aircraft were returning to a pinpoint island base hours away and burning limited fuel supplies, mistakes in dead reckoning could be deadly.

The “Navigator’s Information File” of the Army Air Forces advised: “In the Central Pacific celestial navigation is used in conjunction with dead reckoning on all missions. Many of the islands and atolls are plotted in error from 2 to 10 miles, usually eastward or westward. Interpretation of sun lines and fixes is important. Radio facilities are not always available in this area and you cannot always depend upon them because of local disturbances. Be careful when you use clouds for pilotage. Cumulus often builds up around islands, but shadows of clouds also look like land….”

Twelve hours after taking off, Dogpatch Express settled gently onto Funafuti’s dusty coral strip and Deasy taxied the bomber to a stop, guided by a ground crewman’s hand signals. On the ground again, the men of Dogpatch Express walked around their aircraft, checking it for damage. Some elevator fabric was torn away. There was the jagged flak hole behind and above the copilot’s seat, big enough for Yankus to put his fist through. Joe Deasy found the razor-sharp metal in his parachute pack where, its energy finally spent, it stopped less than an inch from the pilot’s spine.

“Brooks Didn’t Make it”

A ground crew corporal skidded up in a weapons carrier, wooden planks along its sides for seats, to take the crew of Dogpatch Express to the mess hall. There an intelligence officer debriefed them. He gathered information about enemy fighters, how many and what tactics they used, how aggressive they were. He made notes about the antiaircraft reception, bomb hits, fires started, what color the smoke was, and how far out the smoke could still be seen.

After their debriefing and after a few bites to eat, the men walked back to the flight line. They counted 22 B-24s, all but one. Word got around about Lieutenant Russell Phillips’s crew. A burst from a Zero’s 20mm cannon had raked the side of Super Man, practically rolling the plane out of control.

Phillips struggled mightily to get back to Funafuti. There were hundreds of holes in his plane, plus the right rudder was half gone. Six men of Phillips’s crew were hurt, including Scearce’s good friend, Harold Brooks. Brooks had been rushed from Super Man to the field hospital on Funafuti, rushed the short distance from the plane to the hospital, but only after the agonizingly slow flight of nearly six hours from Nauru.

Scearce returned to the tent that housed the enlisted men on his crew. He sat on his cot, untied his boots, and pulled them off. He lay down and stared straight up at the sloping canvas ceiling, turning his head when Jack Yankus stepped in. Yankus had lingered at the flight line with Dogpatch Express where he surveyed the severed oxygen line, checked for other damage, and got the latest news. Yankus said, “Brooks, uh … Brooks didn’t make it, Herman.”

A man injured on a bombing mission in the Pacific had hours to go, perhaps longer than any soldier in any theater of the war, before getting to a field hospital and a surgeon. There was little his crewmates could do beyond basic first aid, try to stop the bleeding, try to position the man correctly, give him morphine, maybe stop the pain. He would wait for hours, riding in his bomber back to a waiting ambulance and a field hospital.

Scearce responded weakly to Yankus, “That’s bad.” He sat up without looking back toward his friend, pulled his boots on again, and walked back to Dogpatch Express. At the plane, Scearce climbed through the open bomb bay and went to his gun position. He inspected his gun and decided against changing the barrel. Some gunners changed their barrels religiously, to be sure the gun would be straight and true for the next mission. A long burst from the .50s could generate enough heat to damage the barrel, but Scearce believed that a proper inspection of the gun was more sensible than frequent barrel changes. He would install a new barrel if and when the gun needed one.

The radioman got down on his knees on the floor of Dogpatch Express under the right waist window. In the silent, parked bomber he knelt for a moment on his flak jacket, still flattened on the metal floor. Kneeling there he scooped up spent .50-caliber machine-gun shell casings with both hands. He wondered whether Brooks had used his weapon, whether, just maybe, Brooks had gotten a burst into a Zero, possibly even the one that killed him.

Scearce dropped the spent brass into a galvanized metal bucket. After picking up the last few casings from the bottom of the airplane, he turned to check the left side and saw that Yankus had already cleaned up his area. Scearce carried the bucket forward, dropped out of the plane through the bomb bay, and set the bucket of shell casings on the ground beside a tool cart. Maybe tomorrow the crew chief would empty the casings into the island’s waste dump.

After-Action Report: “Damage to Installations and Material was Heavy”

Intelligence information gathered from each air crew just returned from the Nauru mission was compiled and compared, and photos developed and analyzed, until an accurate accounting of the bombing results was completed. Maj. Gen. Willis Hale endorsed the final report, which was then sent to CincPac, the office of the Commander in Chief, Pacific Command.

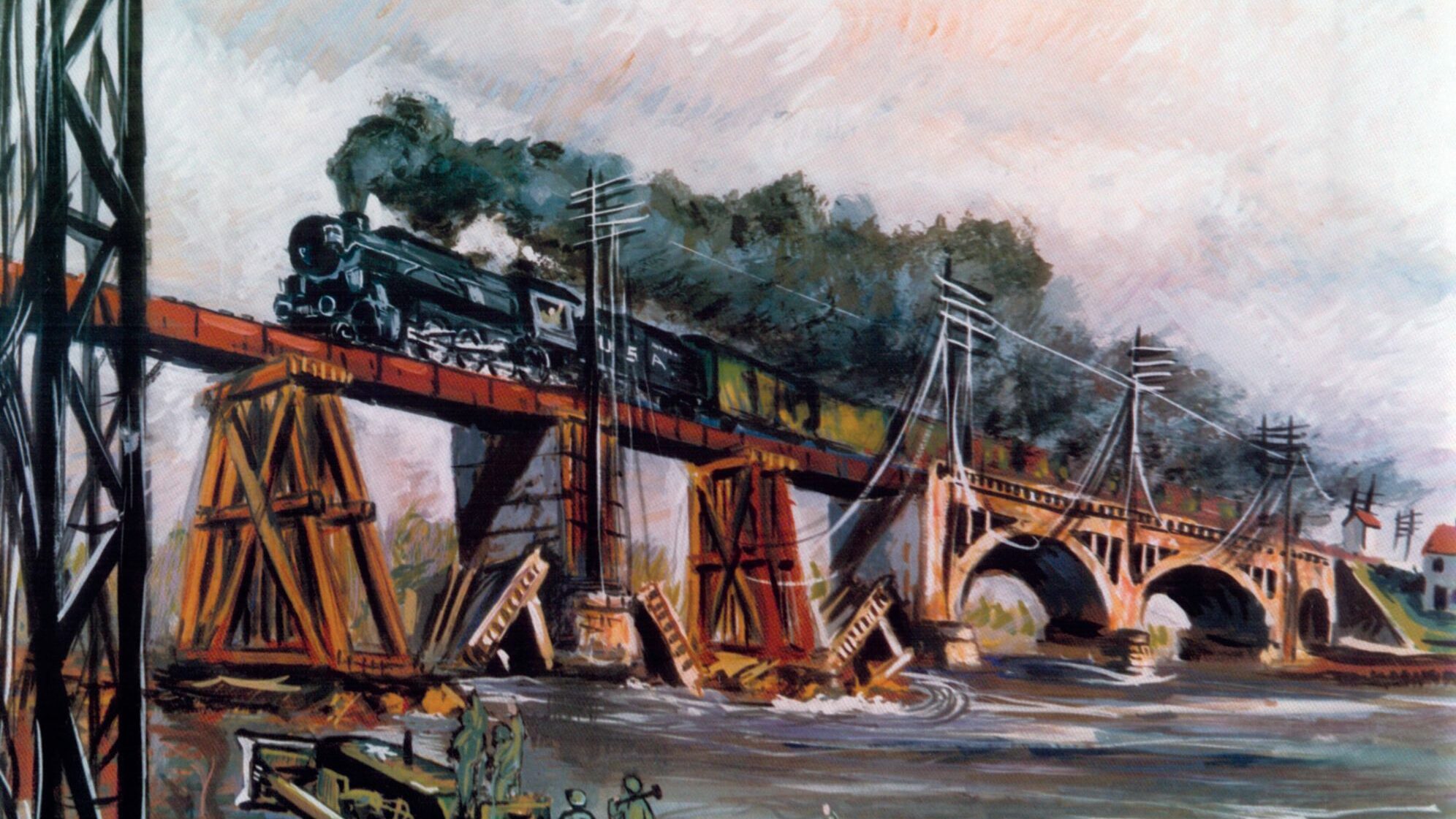

The report described a highly successful mission: “All bombs dropped hit target except eight…. Damage to installations and material was heavy. Personnel casualties were extremely heavy. Large fires were observed in all bombed areas … a group of approximately twelve buildings in the center of the runway were destroyed…. Phosphate Plant #3 was completely demolished by at least two direct hits … at least three direct hits were made on Phosphate Plant #2 … this plant was completely destroyed. Six bombs destroyed at least three large warehouses, thirteen buildings, eleven small railroad cars, stock storage pile, two water tanks supplying plant … Diesel power plant, main plant elevator building, one water tank, five cisterns, seven buildings and water distillation plant badly damaged. A train of six 500-lb bombs burst in residential area. Large fires were started which were increasing in scope when last oblique photo was taken … most buildings in immediate area were destroyed. At least ten fragmentation bombs put out of action three machine gun positions and one heavy antiaircraft. At least fifteen motor vehicles were destroyed. Four two-engine bombers were completely destroyed, two of which burned … at least three one-engine fighter planes were destroyed.”

The report also described damage to American bombers, crediting all of it to attacking Japanese fighter aircraft, and noted that 12 airmen were wounded and one killed. The missing B-24, low on fuel, had landed at Nanumea, where it gassed up and made the hop back to Funafuti.

General Hale concluded his report, stating, “It is believed that this operation was the first successful attack against a valuable Japanese industrial installation since the raid on Tokyo. It was probably the longest offensive air operation of the war to date—the target was in excess of 3,200 miles by air from the home base of the attacking unit.”

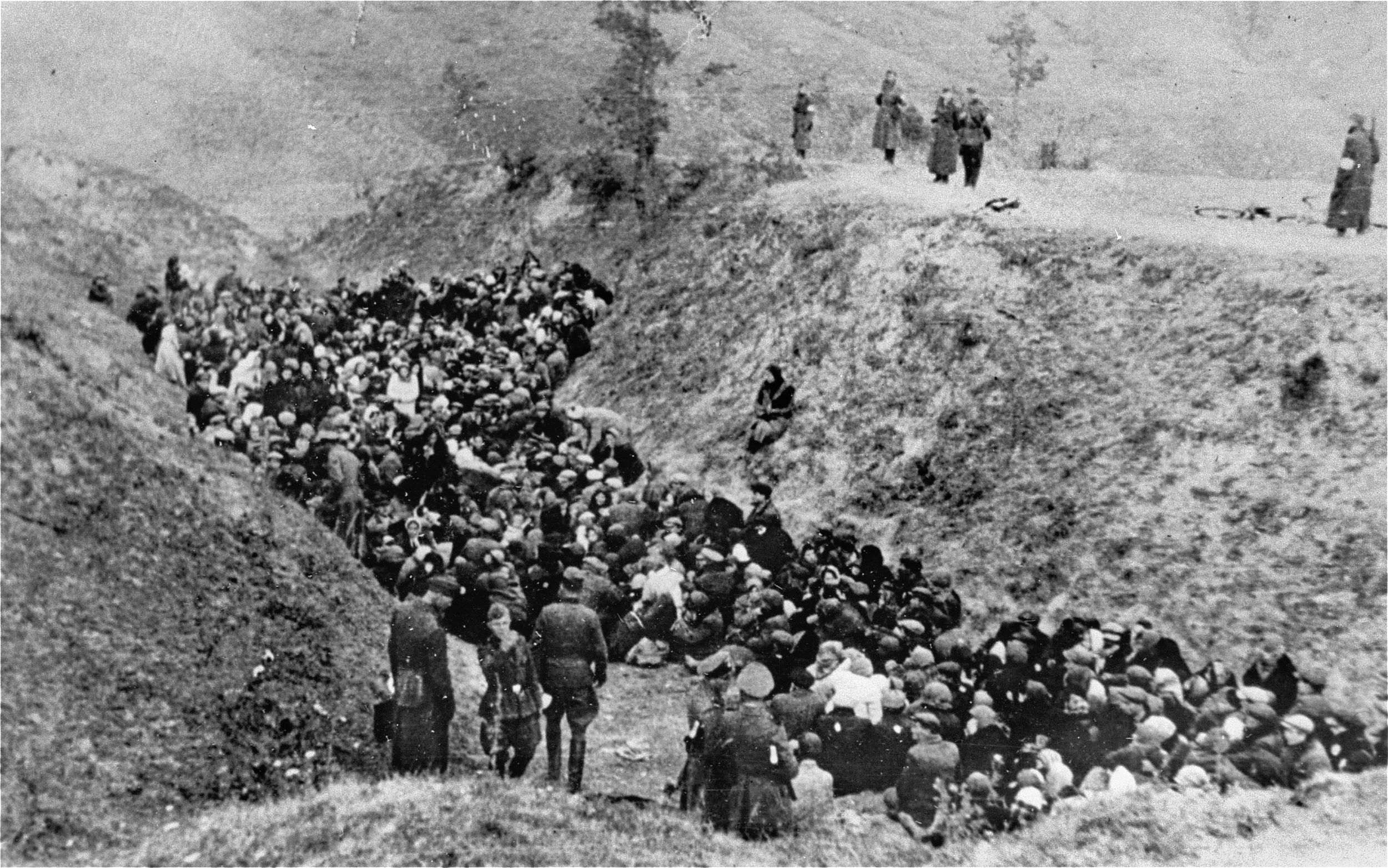

After the attack, Nauru’s Japanese defenders rounded up their prisoners. These prisoners, 191 employees of the British Phosphate Commission, had been left behind when their colleagues evacuated ahead of the Japanese landing eight months before. Because they feared that the aerial bombardment was a precursor to an American invasion, an invasion that would never come, and because they would not risk the prisoners’ cooperation with the enemy, the Japanese executed them all.

The 11th Group crews on Funafuti prepared for another strike mission, but Dogpatch Express would not be in the lineup. Ground and flight crews spent the evening fueling and “bombing-up” undamaged airplanes for a raid against Tarawa atoll while repairs to planes damaged in the Nauru raid continued.

Repair and maintenance work on Funafuti was slow and improvised. As an advanced staging base, Funafuti was lightly equipped. The “72 hour kits” carried to the island in the bomb bays of the aircraft were adequate for three days’ maintenance, but repair to some of the damaged aircraft was beyond the capabilities of the base. The sheet metal work to Dogpatch Express was completed on Funafuti, but the severed oxygen line would wait until the plane returned to Oahu.

Life on Funafuti

A crew from Life magazine was on Funafuti, having accompanied the group on the flight from Hawaii via Canton. It seemed strange to the crewmen having the magazine people there because the airmen were not used to being newsworthy. But the Nauru raid was the first strike by American heavy bombers against a Japanese industrial target, and it seemed that the Air Corps wanted publicity for it. Besides chatting with officers, the Life crew toured the island in little groups, taking pictures and writing in notebooks while their officer escort pointed out Funafuti’s features.

The largest building on the island was the Missionary Church, a concrete structure with a wood-framed roof thatched with pandanus, the same plant natives used to weave mats. The church was built by the London Missionary Society on the west side of the island near the lagoon, almost even with the northeast end of the runway. It provided an easily recognizable visual reference for pilots. Native huts, about 60 of them in all, were on the lagoon side protected by the crescent curve of the island. The huts were rectangular, with corner posts of strong coconut trunks. Roofs were similar to the church, timber framed and thatched with pandanus. The sides of the huts were also thatched and made so they could be rolled up and tied open during the day. Gentle waves in the lagoon lapped at the beach, but on the eastern side, the ocean’s waves met the shore with noisy crashes and salty spray.

Funafuti was short on amenities, but the island did have the advantage of a friendly, cooperative native population, and the American servicemen at Funafuti were amused by the pretty, dark-skinned, and topless girls among the island’s several hundred natives. But the men were supposed to keep their distance from native women and “the novelty wore off soon enough,” Yankus recalled.

Many of the natives spoke English, learned from the London Missionary delegation. They were friendly. In fact, they had worked themselves to near exhaustion months before, helping men of the 5th Marine Defense Battalion, two companies of the 3rd Marines, elements of Navy Scouting Squadron 65, and a group of Seabees unload gear and equipment from their landing vessels.

A quirk of time and location had turned this place, an island paradise, into a wartime bomber base. As beautiful as it looked, like a Robinson Crusoe shipwreck setting, it was a sorry place for a military operation.

Each morning, the relentless equatorial sun heated aircraft and tools so quickly that it was difficult to work. Ground crews who serviced the several Marine Vought F4-U Corsair fighter planes and the Navy’s Kingfisher scout planes on Funafuti knew how critical it was to keep tools and equipment covered or put away because salt and sand were everywhere. In the afternoon, it rained, cooling things a bit, but the sun quickly cooked off the rain so that humidity joined forces with the heat to make working conditions miserable.

The coral runway built by the Seabees should have been as solid as concrete, but rain prevented the live coral used to build it from curing properly. The coral packed like gravel, rutted and dusty. When aircraft took off or landed, dust from the runway created storms of minute abrasive particles. The northeast to southwest orientation of the single airstrip offered no alternative if the predominantly easterly winds shifted to the southeast. In those conditions, pilots met a 90-degree crosswind, challenging enough with a heavy load on takeoff, but nerve-racking with low fuel, an engine out, or battle damage on the return.

Freshwater was provided by distillation units. The Marines and Navy men supplemented the water supply by catching rain runoff in barrels placed under the drape of their tents. In the middle of the island was a pond, really more of a swampy bog, that the Seabees had to partially fill when they built the runway, but the bog was of little practical use except to the island’s mosquito and rat populations.

The enlisted men of each bomber crew shared a tent. The canvas tents lacked floors and electricity and were equipped with cots. Officers were housed in a separate area, also in tents but with electricity from gas-powered generators.

Equipment for servicing bombers was barely adequate. Ground crewmen had two Cletracs, slow, tracked vehicles, more tractor than truck, for servicing aircraft. Cletracs were excellent for towing and parking aircraft but dreadfully slow for pulling gas trailers to refuel airplanes. A mess hall and barracks were planned, but for now the men made do with field kitchens and tents.

Eddie Rickenbacker on Funafuti

There was a one-room hospital on Funafuti, completed in November 1942. It had 40 field beds and was staffed by two doctors, a dentist, and 22 Navy corpsmen. They boasted that the famed World War I fighter ace Eddie Rickenbacker was among their first patients. Rickenbacker was one of seven survivors of an October 1942 B-17 crash in the ocean. Survivors drifted for weeks in their rafts before being rescued by a Kingfisher aircraft.

Rickenbacker and his men were taxied half an hour across water, lashed to the aircraft’s wing because the rescue made the plane overloaded for flight. The Kingfisher finally met a PT boat that took Rickenbacker the rest of the way to Funafuti.

There were a few bunkers for personnel, built by the Marines, but not enough for every man’s protection. There were shallow slit trenches and some holes where palm trees had been bulldozed down, but most of the island was too low for much digging. There were a few revetments for aircraft, but not enough to protect them all. The group’s best defense on Funafuti was secrecy, but there were only so many places from which B-24s could have attacked Nauru.

The Japanese may have sent a plane to follow the Americans as they returned, or they may have reconnoitered Funafuti undetected. The briefing officer on Kahuku who told the bomber crews bound for Funafuti that the Japanese would not know they were there had made no promise that the secret would last.

In fact, sometime during the night of April 20, just hours after the last B-24 returned, three twin-engined Mitsubishi aircraft took off from a Japanese air base on the island of Betio in the Tarawa atoll with full bomb loads. The Japanese planes turned south-southeast, headed for Funafuti.

“Air Raid! Air Raid!”

Scearce made his way to his crew’s tent before curfew. An ordnance truck, a bomb loader with a small crane attached to the rear, was parked nearby. Scearce assumed that whoever used it last must have parked it near his own tent. Parking it in the shade of coconut trees in the crew quarters area would keep the vehicle and its steering wheel a little cooler than parking it beside the runway.

Inside the tent, the enlisted men of Dogpatch Express chatted quietly. They talked about Nauru and the coming strike against Tarawa. They speculated about their next mission and whether Lieutenant Schroeder would get his bombs on target next time. Conversation faded quickly because the men were exhausted; they had not slept much the night before.

Shortly after midnight, the air raid signal sounded. A shrill, piercing siren, 10-second blasts at five-second intervals, caused the men to stir. Marines ran from tent to tent, yelling “Air raid! Air raid!”

Scearce and his heavy-eyed crewmates halfheartedly swung their legs to the ground, assuming this was someone’s idea of a joke or maybe a drill. Then a Marine Corps antiaircraft battery opened fire, boom … boom … boom … and the men knew immediately it was no drill. They scrambled in the dark to pull on flight suits and ran out of their tents. Now aircraft could be heard, but the direction was indistinct, there was just the sound of unsynchronized aircraft engines overhead. A familiar voice shouted, “Get in the hole!”

There was a shallow hole near the crew’s tent, and Scearce piled in on top of his crewmates. Falling bombs made menacing whistling sounds while explosions threw orange flashes about treetops and tents, casting silhouettes of men running. The smell was pungent, like sulfur or a spent shotgun shell.

Forty terrified villagers huddled inside the Missionary Church, praying that its concrete walls would save them. Marine Corps Corporal Fonnie Black Ladd ran into the church, calling for the people to get out, imploring them to get away from the church, to take cover elsewhere because the church was an obvious target for the Japanese.

A salvo of bombs stepped toward the hole containing the men of Dogpatch Express, its pattern of explosions growing louder and closer. Scearce held the sides of his helmet with both fists clenched, trying desperately to fit under it. Knees to his chest, teeth gritted, and eyes squeezed tight, Scearce knew the next one whistling toward them would be very close.

With a terrific whang the bomb hit the ordnance truck parked just a few feet away. Dirt and metal rained down. In the next second, a hissing cylinder landed in the crew’s tiny hole, right on top of Elmer Johnson. For a moment, the men of Dogpatch Express could hear nothing, then the sensation of sound returned with a shrill ringing, and the powerful stench of explosives filled their nostrils. Scearce’s mind raced: “This is it,” he thought. The metal cylinder continued to hiss, and the men did not move, afraid they could cause it to explode.

Assessing the Damage

The hissing weakened, and the whistling of falling bombs and their terrific explosions finally stopped. Voices were audible now, agonized screams, cries for help, shouts, men giving orders. The enemy aircraft could be heard again, leaving the island toward the north, toward Tarawa. There were crackling and popping and strange metallic groans; an aircraft was burning. In the dim light of early morning, with gray-black smoke stinging their eyes, the enlisted men of Dogpatch Express accounted for each other.

“It’s a damn fire extinguisher,” Johnson said. The cylinder that landed on him, the hissing object that the crew feared was a bomb, was instead the damaged pressure tank of a brass fire extinguisher blasted from the ordnance truck when the truck took a direct hit.

Men had jumped under the truck for cover. Scearce thought there were four. Parts of bodies were strewn about, and one man still lay under the demolished truck. Scearce could tell the man was a staff sergeant by his stripes, but could not recognize him because his face and the top of his head were gone.

Corpsmen rushed to help the injured while others fought fires. Casualties were lined up by the airstrip in the shade of planes’ wings. As bulldozers cleared debris, the worst of the injured were placed aboard a plane to be sent back to the U.S. mainland. Others went to a hospital on Fiji, 670 miles south. Some injured men refused to be evacuated, insisting on staying with their crews.

One Liberator was burned completely. Smoking radial engines lay on the coral runway, propellers bent and folded under as if they were made of rubber. The twin vertical tail planes seemed intact, though the rudder fabric was scorched away. The tail section stood on the coral, pitched forward, as if the plane were in a steep dive.

Other aircraft were holed by shrapnel, tires blown out, and plexiglass shattered. Some of the planes could be repaired, and some would be scrapped and used for parts to keep others flying. Bomb-loading equipment, radio gear, the mess area and tents were damaged, burned, or blown down by the concussion of bombs. The walls of the Missionary Church stood, but its roof was gone and its interior was gutted. A bomb had crashed through the thatched roof and exploded, bringing roof timbers and flaming, dried pandanus down into the building vacated by the villagers a moment before.

A young native man named Esau Sepetaina lay on his back as if resting, arms at his side, his chin, mouth, and left ear visible, but the rest of his head was smashed like a melon. He was the only native killed in the raid, and he died beside one of the few true personnel bunkers in Funafuti’s shallow earth, his feet just inches from the edge.

On to the Next Mission

On the morning after the air raid, Scearce, Lipe, Yankus, and Johnson stood with a handful of other men near the broken remains of the ordnance truck, watching helplessly as medical corpsmen lifted one of the dead men from the wreckage. They felt hollow, sick, and at the same time relieved it was not them. Beside the wrecked truck lay its splattered and torn seat and the vehicle’s battery, and beyond them a Life magazine photographer captured the scene on film.

On April 21, Dogpatch Express took off past the still smoldering remains of a sister aircraft. The bombers in the lineup for the next mission stayed behind, scheduled to hit Tarawa the next night. The long flight back to Hawaii, with its overnight stop at Canton, lacked the sense of purpose and anticipation of success that sustained the men on the way out. The return flight felt like retreat. The men felt beaten.

The Japanese air raid consisted of a few medium bombers making several passes at night. The enemy planes had traversed the island, back and forth, as if without concern about the three Marine Corps antiaircraft batteries. The Japanese took their time, working thoroughly and deliberately, taking advantage of a full moon’s light on Funafuti’s white coral runway. Their show of skill was sobering to the American bomber crewmen, particularly the men of Dogpatch Express, who had seen their bombs explode in the water just off the sandy beach of Nauru.

Excellent story about the air war in the Pacific Theater. It truly reveals the dangers airmen faced on missions, as well as when at their bases.