By Kevin L. Cook

A caravan of traders bound for Santa Fe left Cantonment Leavenworth near the Missouri River on June 3, 1829, escorted by four companies of the 6th U.S. Infantry under Major Bennet Riley. Two months later, as the soldiers waited near the Arkansas River for the eastbound caravan to reenter United States territory, a force of 300 Indians, well mounted and armed with guns, bows and arrows, and spears, charged the camp. The soldiers repelled the attack but lost one man, 54 oxen, and several horses and mules. “If we had been mounted, we could have beaten them to pieces,” Riley said.

Recruiting a New Kind of Army

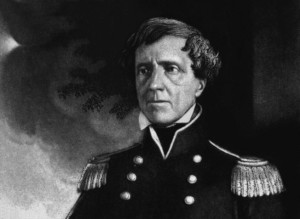

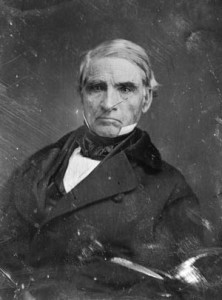

In response to the attack, Missouri senator Thomas Hart Benton authored legislation to add a mounted arm to the 6,200-man army. Soon afterward Congress acted on Benton’s motion in March 1833. The War Department appointed officers in the new regiment. Colonel Henry Dodge, head of the militia-like Battalion of Mounted Rangers, was named to command the new mounted force. His second in command was Lt. Col. Stephen W. Kearny, who was enjoined to recruit “healthy, active, respectable men of the country.” Kearny’s orders specifically mentioned recruiting from within the interior of the country, a response to Arkansas Territory Delegate Ambrose H. Sevier’s complaint that army troops “consisted generally of the refuse of society, collected in the cities and seaport towns.”

[text_ad]

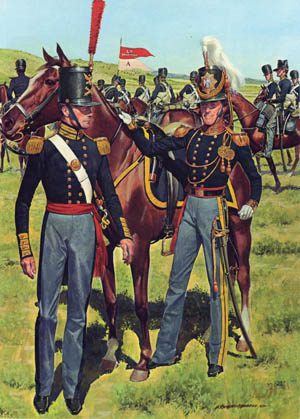

Philip St. George Cooke, a dragoon first lieutenant, was recruited in western Tennessee. He said the prospect of exploring the West excited “the enterprising and roving disposition of many fine young men.” Similarly, a New York recruit said, “The wild regions of the West, prairies, Indians, are all objects of intense interest to my romantic imagination.” According to a letter in a New Hampshire newspaper, the planned expeditions would cross country “full of game of every sort, interspersed with prairie and wood land, the latter free from underbrush, so that it may be passed freely in any and every direction; and as these expeditions will be ordered in the summer, they will be delightful recreations to active spirits.”

Recruiters were authorized to tell candidates they would be well clothed and kept in comfortable quarters in winter. Additionally, a magazine reported that one commander “permits the performance of no menial service from any member of his detachment.” Recruits were also told that they were equal in prestige to West Point cadets and would not receive severe military discipline. Land and emigration were further inducements. “When discharged, each man receives in money an allowance of pay and subsistence to the place of enlistment,” one newspaper reported, adding helpfully that the men could combine that sum with savings from their regular army pay to purchase western land.

The recruits, 10 companies of 71 men each from nearly every state, began to arrive at Jefferson Barracks in early May 1833. At the post, 10 miles downriver from St. Louis, the new dragoons found that contrary to what recruiters had told them they had no uniforms to wear, nowhere to sleep, and nothing to cook with. They had only old muskets for training and no horses until early October. By then there were as many as eight desertions per night, including corporals and sergeants. One afternoon, the dragoons stopped building their stables to witness a deserter’s punishment. Several lashes with a cat-o’-nine-tails brought blood. Shrieks rent the air, and by the 50th stroke the prisoner had fainted. He was carried to the hospital, where salt and water were rubbed into his wounds.

On November 20, five companies of dragoons began a march to Fort Gibson, near present-day Muskogee, Oklahoma. In the rear were 18 deserters and other prisoners who walked handcuffed, some with a cannonball chained to one leg. The dragoons reached the fort on December 17. Dodge found no arrangements for rations for the men or horses, and they settled in for a cold, hungry winter. More recruits gathered at Jefferson Barracks and made the 450-mile journey to Fort Gibson in May and June 1834.

Riding to the Washita River

The government wanted to establish peaceful relations with local Indian tribes, and between the western tribes and the eastern tribes that had been forcibly moved west. On May 19, 1834, the Regiment of Dragoons was ordered to make a tour through the Indian territory along the Mexican frontier. Colonel Henry Leavenworth, commander of the left wing, vowed without apparent irony that there would be a peace made with the Pawnee, “if we have to fight for it.”

Artist George Catlin obtained permission to accompany the regiment and waited at Fort Gibson for two months for their departure. He warned that the expedition was leaving two months too late in the season, which would make it difficult to find grass, game, and water. The last three recruits arrived at the dragoon camp on June 12, and three days later eight dragoon companies, about 500 men, began their journey from their camp near Fort Gibson. The ninth company escorted traders to Santa Fe. The expedition’s officers were Cooke; 1st Lt. Jefferson Davis; Captain Nathan Boone, son of famous frontiersman Daniel Boone; and 1st Lt. T.B. Wheelock, ordnance officer and official chronicler of the campaign.

On June 21, about 30 tribesmen from the Osage, Cherokee, Delaware, and Seneca tribes joined the expedition. They were to serve as guides, hunters, interpreters, and “representatives of their several nations, should we meet with the Pawnee.” The Osage brought along two young Kiowa and Pawnee women they had taken prisoner. Their imminent return was expected to “conciliate the Indians, and pave the way to desirable treaties.” In camp, the expedition’s surgeon pronounced 23 men unfit to continue and sent them back to Fort Gibson.

Dodge and 40 men moved ahead to meet Leavenworth and two infantry companies at the Washita River. A few days later, several officers at the head of the column spotted a buffalo herd and gave chase. Catlin saw Leavenworth and his horse disappear into a hole and quickly rode to the spot. “I asked him if he was hurt, to which he replied, ‘No, but I might have been,’ when he instantly fainted,” Catlin wrote. Catlin rode with the colonel for several days and noticed a bad cough and a change in Leavenworth’s overall demeanor. Leavenworth told him, “I have killed myself in running that devilish calf; and it was a very lucky thing, Catlin, that you painted the portrait of me before we started, for it is all my dear wife will ever see of me.” When the dragoons reached a small infantry camp near the Washita River on June 29, three officers and 45 men were sick from the heat and 75 horses and mules were disabled.

Ten Days’ Provisions

On July 3-4, the expedition crossed the Washita, using a canvas boat covered with gum. Baggage wagons crossed on a raft built from canoes lashed together. The horses and mules had to swim across and several head were lost. The ailing Leavenworth reversed his earlier decision to command in person. He ordered Dodge to take 250 men to the Pawnee villages with the regiment reorganized into six 42-man companies. Some 109 men were left for duty, with 86 sick, including Leavenworth.

The dragoons continuing west were ordered to take nothing with them but a change of shirts. Wagons, pack horses, and tents were left behind. They took only 10 days’ provisions and 80 cartridges per man. On July 7, the dragoons found pony tracks and recent fires, presumably left by Indians. Late that night, a shot pierced the silence followed by the sound of horses snorting and running and cries of “Indians! Indians! Pawnees!” A sentinel thought he saw an Indian creeping out of the bushes, Catlin said. “And as the poor creature did not advance and give the countersign at his call, nor any answer at all, he let off! and popped a bullet through the heart of a poor dragoon horse” that had strayed and triggered the panic. Troops spent the next day recovering all but 10 of the stampeded horses.

Early on July 14, dragoons saw a group of Indians on a nearby hill. Dodge halted the columns, unfurled a white flag, and rode toward the Indians with his staff. A dragoon wrote that during this anxious moment, “every voice was still and even the horses seemed instinctively to maintain order & silence.” Catlin joined the advance as it came to within a half mile of the Indians. “The white flag was sent a little in advance, and waved as a signal for them to approach; at which one of their party galloped out in advance of the war party, on a milk-white horse, carrying a piece of white buffalo skin on the point of his long lance,” Catlin wrote. “He wheeled his horse, and dashed up to Col. Dodge with his extended hand, which was instantly grasped and shaken.”

Gradually, the whole band of about 30 Comanche approached and shook hands, with “eagerness to convince us of their disposition to be friendly,” Wheelock recorded. Their village was two days away, and a day’s journey beyond that was a Wichita village. In camp that night, Dodge told the Indians that President Andrew Jackson, “the great American captain, had sent him to shake hands with them; that he wished to establish peace between them and their red brethren around them, to send traders among them, and to be forever friends.”

The expedition reached the Comanche camp on July 16, and 100 mounted Comanche rode out to welcome it. “Six nations, some of whom had but recently been at war with each other, shake hands together,” Wheelock wrote. A chain of peaks, some 2,000 feet high, was within sight. Behind these lived the Wichita, whom the Comanche and Wheelock called Toyash. Catlin mistakenly said the reddish granite peaks were “without doubt, a huge spur of the Rocky Mountains.”

“Sickness and Desertion Had Much Reduced Our Little Band”

The number of sick dragoons continued to increase. On July 18, Wheelock wrote that the command was delayed for two hours waiting for six litters, including Catlin’s. “Our sick encumbered us so much that Colonel Dodge resolves to leave them behind,” Wheelock noted. The men had been ordered to make 10 days’ provisions last for 20, but buffalo had become scarce, and many men were completely out of provisions.

The next day, 75 men, including 39 sick, were left in camp. Only 183 men continued. “Sickness and desertion had much reduced our little band, and our horses were almost worn out with fatigue,” a dragoon wrote. “Our situation was now extremely precarious; starvation seemed to stare us in the face on the one hand, and should the Indians prove unfriendly, we had but little chance of escape.”

Near the Toyash village on July 21, about 60 Indians came out to meet the dragoons and begged Dodge not to fire on them. “We were on the brink of starvation, having nothing to eat save what we got from those Indians,” Sergeant Sam Evans wrote. “The squaws bring in roasting ears mellons green pumpkins squashes &c which they trade to us for buttons tobacco strips off our cloth shirts and many other articles we had to dispose of. I have seen a good cotton shirt sell to squaws for two ears of corn.”

Meeting With the Pawnee

The next day, Dodge met in council with Toyash warriors and chiefs. He began, “We are the first American officers who have ever come to see the Pawnees; we meet you as friends, not as enemies, to make peace with you.” He pointed out that the dragoons had found the Comanche defenseless but treated them with kindness. “The American people show their kindness by actions, and not by words alone,” Dodge said. He asked about a white boy taken in the spring and offered to exchange the Pawnee girl who accompanied the expedition. He said he would not leave without the boy and information concerning a ranger who was taken a year earlier. When the boy was brought to the council, the youth exclaimed: “What! Are there white men here?” Dodge asked his name and he promptly replied, “Matthew Wright Martin.”

Dodge immediately ordered the Indian girls brought in, and they were quickly recognized. “The chief rose and took Dodge in his arms, and placing his left cheek against the left cheek of the Colonel, held him for some minutes without saying a word, whilst tears were flowing from his eyes.” Catlin’s friend continued. “From this moment the council, which before had been a very grave and uncertain one, took a pleasing and friendly turn.”

The leaders met again on the morning of July 23. Dodge said he was sorry that some dragoon horses had gotten into a cornfield the previous night and offered to pay for the damages. “It is not my wish to disturb your property in any manner,“ he observed. “White men will always be just to you.” He asked that some Indian leaders return with the dragoons.

While Dodge and a Comanche chief discussed the Kiowa girl the dragoons had brought in, 20 or 30 mounted Kiowa rushed into camp. The Kiowa did not know about Dodge’s intention to return the girl, “and consequently presented themselves in a warlike shape, that caused many a man in camp to stand by his arms,” Wheelock reported. He said Dodge explained and “gradually led them into gentleness.” A relative embraced the girl and shed tears of joy that she had been returned to the tribe.

The next day a council was held among the Comanche, Toyash, and Kiowa, with more than 2,000 mounted and armed Indians present. “You and the Indians who came with us have long been at war with each other,” Dodge said. “It is time you were at peace together.” On the morning of July 25, some 15 Kiowa, including the chief, were the first mounted and ready to return with the dragoons. Some Comanche, a few Toyash, a released black captive, and the Martin boy, carried by Sergeant Evans, joined them.

Two days later, the group reached the sick camp and found 29 sick, plus two officers and Catlin. The next day there were 43 sick; seven had to be carried in litters. “We all now feel our situation hunger thirst and a burning sun almost sufficient to contract any disease and the pale sallow sun burnt features plainly showed the men cannot endure it much longer,” Evans wrote. The dragoons subsisted on whatever stray buffalo they managed to kill. “Nearly every tent belonging to the officers has been converted to hospitals for the sick; and sighs and groaning are heard in all directions,” noted Catlin, who was unable to ride his horse and rode for eight days in a baggage wagon with several sick soldiers, most of whom were delirious.

Dodge decided to return to Fort Gibson instead of Fort Leavenworth, as originally planned. While the party rested and cured buffalo meat on August 5, a message arrived saying that Leavenworth had died on July 21. At the Washita camp 150 men were sick. At last, on August 15, Dodge, his staff, and the Indians arrived at Fort Gibson. The route through bushes and thorns was so rough, said one dragoon, that it “had proved terribly fatal to clothing, and the greater part of the command were literally half naked.”

For the next nine days, groups of dragoons arrived at Gibson, including Kearny’s command from a sick camp on the river. Many of the men returned “merely to die and get the privilege of a decent burial,” observed Catlin, who watched from his hospital bed. “Perhaps there has never been in America a campaign that operated more severely on men & horses,” Dodge wrote. “The excessive heat of the sun exceeded anything I ever experienced. I marched from Fort Gibson with 500 men and when I reached the Pawnee Pict village I had not more than 190 men fit for duty. They were all left behind sick or were attending on the sick.”

The following summer, Dodge led the dragoons to the Rocky Mountains through present-day Kansas, Nebraska, and Colorado. He was appointed governor of the original Territory of Wisconsin in 1836, and became a senator from the new state of Wisconsin in 1848. The new mounted arm prospered as well. Congress added a second regiment in 1836, and by August 1861 all six mounted regiments were designated cavalry. Three months later, Brig. Gen. Philip St. George Cooke took command of the Cavalry Reserve of the Army of the Potomac. His son-in-law, James Ewell Brown Stuart, made something of a name for himself with the Confederate cavalry. His nickname was “Jeb.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments