By David H. Lippman

By December 1943, the phrase “sunny Italy” had evolved from being a travel agent’s selling point to becoming an ugly joke for the British and American troops of the Allied Fifth Army, advancing north from Naples to Rome. Rain and snow turned ground to mud and made roads impassable. Valleys were seas of black mud. Troops on the mountains created shelters behind rocks and in caves.

American reporter Ernie Pyle described GIs returning from two weeks in the front line as looking “ten years older than they were … Soldiers became exhausted in mind and in soul as well as physically. The infantry reach a stage of exhaustion that is incomprehensible to the folks back home … to sum it up: A man just gets damned sick of it all.”

And the greatest battle of the Italian campaign had not even started yet.

The Monastery Above Cassino

The Allied invasion of Italy had been launched as the logical follow-up to the conquest of North Africa and Sicily. Under the publicity-hungry Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark, the Fifth Army stormed ashore at Salerno, south of Naples, in September 1943, and began a slow, plodding drive toward Rome across mountains and rivers—every one of them seemingly named Volturno to exhausted American soldiers. Finally, the arduous trek was halted along the Garigliano and Rapido Rivers at the base of the Liri Valley—the gateway to Rome—by exhaustion, winter weather, and fierce German resistance.

Stalemate followed along what the Germans called the Gustav Line—a triumph for the Todt Organization’s engineers—with its strongpoint the town that barred the entrance to the Liri Valley, Cassino, and the great mountain that stood above it, Monte Cassino.

The market town was typical of central Italy —four churches, prison, railway station, high school, orchards, vineyards, oak woods, a working Roman thermal bath, and 22,000 inhabitants. But looming just above it stood one of civilization’s great works, the Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino, brooding 1,600 feet over the town, an all-seeing eye that gazed in every direction.

The monastery dated back to ad 529, when St. Benedict sought to headquarter the brotherhood that bore his name in a place where his monks could worship in security during the violence of the Dark Ages. The monastery that resulted became the worldwide headquarters of the Benedictine order. Working by candlelight, Benedictine monks laboriously copied the works of ancient authors, creating miniatures and frescoes that became the basis for art across Europe, and sang Gregorian chants. When the new monastery was built in 1349 after a devastating earthquake, it was a huge building with five courtyards and 15-foot-high walls that were 20 feet thick at their base, and it was accessible only via a five-mile long hairpin track. The monastery, the repository of ancient manuscripts of legendary authors Tacitus, Cicero, Horace, and Virgil, was the blueprint for similar ones throughout Europe and for centuries was host to pilgrims, students, and tourists.

The Gustav Line

By the time German General Heinrich von Vietinghoff’s Tenth Army began digging trenches and bunkers around the mountain’s base in 1943, the Monte Cassino abbey was one of the sacred sites of Christianity. But it was also one of the finest defensive positions in Europe, and the German soldiers (Landsers) digging foxholes around it were among the finest defensive infantrymen in Europe, lean, hardened men who had been indoctrinated in martial values as Hitler Youth and their bodies toned by physical work in the prewar Arbeitsdienst (Labor Service).

The Landsers were supported by the strongest defenses German engineers could create. Adolf Hitler took a personal interest in the Gustav Line and that ensured plenty of supplies. Engineers laid out interlocked systems of antipersonnel mines and barbed-wire entanglements behind the Rapido and Garigliano Rivers and removed buildings and trees to create fields of fire. They were replaced by bunkers reinforced by railway girders and concrete and built in multilayered lines.

The Germans built 100 steel shelters and 76 armored pillboxes around Cassino. The latter weighed three tons each and could shelter a two-man machine-gun crew. The Germans called them “armored crabs.”

Other pillboxes could accommodate 20 to 30 men, with their light machine guns and a charcoal brazier on which to cook rations. Subterranean passages and trenches connected them to infantry trenches. In some cases, the Germans did not knock down homes and buildings but instead incorporated them into the Gustav Line with heavy layers of crushed stone.

Every one of these barriers was laced with mines and booby traps, a German specialty. The Germans sowed more than 24,000 mines, most of them the S-42 “Schu-mine,” which exploded under only 10 pounds of pressure, blasting off a man’s foot. The S-mines were more frightening, going off at groin height. The Americans called this weapon the “Bouncing Betty.” Both mines came in wooden casings, making magnetic detection very difficult.

To cap this, the Germans blasted open a dam on the Rapido River, which flooded the flat plain before the monastery, turning already soggy terrain around Cassino into a quagmire that swallowed men and vehicles.

Nor did the Germans rely solely on passive defenses. Infantry squads were expected to regularly probe and harass attackers and launch immediate counterattacks.

Reinvigorating the Italian Campaign

Yet the Allies were going to have to muster men and attack through this vile terrain and into the viler defenses. More than the conquest of Rome was on the line. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had put his prestige behind the Italian campaign and now it was sinking. At Tehran in 1943, Soviet Premier Josef Stalin had once again fumed about the lack of an Allied invasion of Western Europe and demanded more action from the British and Americans.

Churchill’s idea to breathe new life into the Italian campaign was to propose an amphibious left hook around the German lines, aiming at Rome. An Anglo-American corps would land at Anzio, while the Fifth Army and its American, British, and French troops would break across the Garigliano and Rapido Rivers, work their way through the Liri Valley, and head for Rome. With the German forces tied down on the Garigliano, they would not be able to stop the assault on Rome. All roads led to Rome in 1944 as they did in Julius Caesar’s day, and Allied control of the Eternal City would cut off all supplies to the German front, trap the Germans in the mountains, and break open the campaign.

The assault would be launched in January, despite awful weather, to take advantage of a period when sufficient landing craft for the invasion would be in the Mediterranean. After the assault, the craft would be pulled out for the invasion of Normandy. It was January 22, 1944, or never—17 days to plan and launch an amphibious assault and its supporting attacks.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt was sold on the idea, and he approved the retention of enough landing craft in the Mediterranean to make the Anzio assault, code-named Operation Shingle.

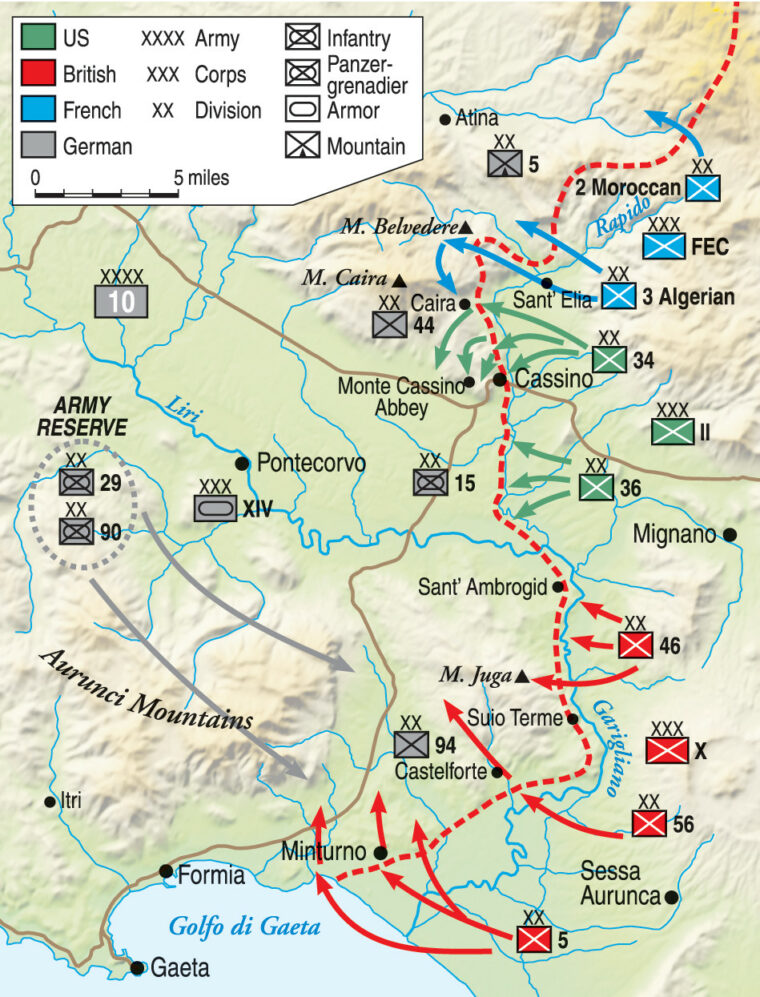

But to tie down the German defenders, Fifth Army would have to attack on the Garigliano line first, with its three corps: the British X, U.S. II, and the French Expeditionary Corps. The French were to advance through the mountains north of Cassino, while the other two corps broke across the Garigliano and Rapido Rivers south of the town and monastery. They began with trouble. Amphibious craft were in very short supply: a Bay of Naples storm had sunk 40 of 50 DUKWs assigned to Shingle, and their replacements came from the two corps assigned to the Garigliano and Rapido crossings.

The French Corps: Half French, Half African

The Battle of Cassino was launched by a force from which little was expected, the French Expeditionary Corps, under General Alphonse Juin, on the Fifth Army’s right flank, north of Cassino.

The French Corps consisted of the 2nd Moroccan and 3rd Algerian Divisions, 50 percent of them French and colonial French, the other half African natives. The former were eager to fight and avenge the humiliation of 1940. The latter were professional soldiers who had spent most of the war square-bashing (drilling) in North Africa, eager to prove their value. What the corps lacked in tanks and vehicles it more than made up in ferocity and mules. The French corps included four regiments of ferocious Moroccan goumiers, bearded mountaineers in striped uniforms who enjoyed close combat with knives, followed by rape and pillage.

Both divisions were fresh arrivals in Italy, refitted with American ammunition and equipment. The first to arrive, the 2nd Moroccan in December, had a unique feature—female ambulance drivers. The Americans wanted them sent to the rear, but the 2nd Moroccan commander, General Andre Dody, exploded at the idea. “The women of France, like the men, are proud to die for their country,” he said.

General Joseph de Monsabert’s 3rd Algerian Division followed, enabling Juin to set up his corps headquarters and work out the best way to send the divisions across the Abruzzi mountain range north of Cassino. With his mountain troops and mules, Juin did not see the mountainous terrain as a barrier. The French North African Army stressed small-unit autonomy, foot mobility, and infiltration.

“You Have No Officers Left”

On the night of January 11, the French Corps opened the battle for Cassino with a two-division, broad-front assault. The 7th Algerian Regiment led off the attack—its first battle—on a pinnacle called Monna Casale. After a 15-minute bombardment, the French moved out to attack the German 5th Mountain Division, a proven outfit of Austrian veterans.

Tragedy struck immediately. A German shell hit a rockpile where all the officers of the 7th Algerian Regiment’s 3rd Battalion were getting their orders, wiping out the battalion leadership with a single shot. The 3rd Battalion had to pull out of the attack. The other two regiments went in anyway. The 1st/7th Algerian took a beating, too. Captain Boutin was hit by a shell and refused to be evacuated. Instead, walking stick in hand, he led his men to take the summit of their objective. A bullet cut Boutin when he neared the top. Sous-lieutenant Vetillard took over and hobbled around, despite a bullet in the hip, encouraging his men to keep attacking. Then an exploding mortar round killed Vetillard. The French finally reached the top of Monna Casale, but it changed hands all day.

The Algerians used up their ammunition, and battalion commanders went up front to distribute bullets. The commander of one company told his 40 surviving men, “You have no officers left. But the 10th Company doesn’t need them. Go, take this peak for me.” The 10th Company did. Finally, the German 85th Mountain Regiment retreated to the Gustav Line.

The Moroccans had an easier time. Equipped with their ancestral dagger, the baroud, the 4th Moroccans gained surprise in their night attack. Jamming barouds into German backs, the 4th Moroccans “pushed on into the night. They were now no longer men, they were there to kill. Grenades exploded in the dugouts and screams came from within; elsewhere the Germans rushed out into the snow, some still in stocking feet. Half-dressed, they rushed toward their weapons pits through bursts of machine gun fire which forced them to throw themselves flat. Some put up a half-hearted resistance but this was soon broken by the relentless tide of hellish giants that surged all around them,” their history recorded.

For four days, the French chased the Germans across the hills and mountains. They bounced across the Rapido and kept pressuring the Germans. But the French took serious casualties and, by January 21, were running short of food and ammunition and were weary from frostbite and exposure. Juin judged that with another division he could break through the crumbling German lines, hook around Cassino, and enter the Liri Valley. But he didn’t have another division. He kept trying with what he had, but the Germans were well dug in on the Gustav Line, and the French were exhausted. Juin called off further attacks on the Cassino massif and consolidated his gains. Patrolling Moroccan goumiers found Italian civilians hiding in caves and they raped the women they caught.

Little Progress

The British X Corps, under General Sir Richard McCreery, went in next on the left coastal flank. Two of the corps divisions, the 46th “Oak Tree” and 56th London “Black Cats” Divisions, had seen their first battle at Salerno and had been in action ever since. Fusilier Len Bradshaw of the 9th Royal Fusiliers, at age 19, was a battalion veteran. After three months of fighting, he did not think he would reach age 21. McCreery put the 5th Infantry Division on the coast, the 56th in the middle, and the 46th on his right. The 5th and 56th would cross the Garigliano and turn right, driving through the Ausente River valley into the narrow Ausonia mountain gorge and into the Liri Valley. The 46th would cross opposite Sant’ Ambrogio and protect the U.S. 36th Infantry Division on its right. The British made a close reconnaissance of the Garigliano riverbank, cleared German mines, and sited their bridging equipment.

The German defense consisted of the 94th Infantry Division, standing on high ground 1,000 yards west of the river. They had plenty of machine-gun positions and 24,000 mines, under General Bernard Steinmetz. The division bore the number of an outfit that had been eliminated at Stalingrad.

X Corps guns opened fire on the evening of January 17, 1944, supporting a British attack into mountainous terrain with few roads and fewer tracks. Mules were the crucial arm of logistics, but X Corps had only 1,000 of them, barely enough to supply the infantrymen up front, let alone carry mortars and artillery. Under the intense pressure, the mules repeatedly broke down, and McCreery had to send in human porters—Cypriots and Palestinian Jews of the Royal Pioneer Corps—to haul bully beef and .303-caliber bullets to the front-line positions.

The 5th Division’s amphibious move against Minturno did not work, and neither did its overland attacks. The division’s 17th Brigade crossed the Garigliano but took appalling casualties in the German minefields. One company of the 6th Seaforths found itself surrounded by tanks, and only a pinpoint artillery barrage saved them. The Germans regrouped and blasted the Scots. The company commander ordered all men to make a break for it. He was killed minutes later, and only one survivor of the company escaped the trap.

By the morning of the 18th, the 5th Division had taken Minturno, but made very little progress; its reserve brigade, the 15th, was sent in, following narrow tracks marked by Royal Engineer tapes, through dikes and ditches. One company got lost and went straight into a minefield, losing a platoon. It took the rest of the night to extract the wounded men.

“Dig or Die”

Meanwhile, the 5th Division’s third brigade, the 13th, took heavy casualties in its drive on Hill 156. They took it and lost it to a counterattack. The 2nd Cameronians warned their men in an operations order: “It is fatal to halt when mortared. Once you are in among [enemy] troops he will stop mortaring. Dig or die.”

The 5th Division had gained a shallow bridgehead and time to breathe. They took advantage of the superb German dugouts, one of which had a fully cooked breakfast ready to eat. The Germans launched counterattacks, which were fended off by artillery and naval gunfire.

The 56th London Division sent in the tough 169th “Queens” Brigade, which consisted of the 2/5th, 2/6th, and 2/7th Queen’s Regiments. By nightfall on the 18th, they were across the river and up on their ridge. The 167th Brigade was assigned a group of hills and ran into heavy machine-gun fire. The 9th Royal Fusiliers headquarters party walked along the wrong railway embankment and into enemy gunfire. The commanding officer survived, but most of his men were killed. The other two battalions were able to take their objectives, but the assault was running behind schedule. German resilience had been underestimated, as was the strength of their firepower and minefields.

At least the 5th and 56th got across their river. The 46th “Oak Tree” Division, supposed to support the American drive into the Liri Valley, was not even able to do that. Just before attacking, the division’s 128th “Hampshire” Brigade saw the Garigliano River turning into a torrent. The Germans had released the sluices of the San Giovanni Dam, and the river was six feet deeper than usual. The 2nd Hampshires and 1st/4th Hampshires had to offload their boats and manhandle them into position for the assault. When the 2nd Hampshires finally crossed, they rigged a cable ferry, but it broke, scattering boats downstream. Others got lost in the torrent and the mist. The 1st/4th Hampshires made 14 attempts to push a cable across the river; all failed. By January 20, the 128th Brigade had to call off its attack, the Hampshiremen badly shaken by the destruction.

The Germans held the high ground and used it to their advantage, with artillery and mortar spotters calling in fire on British ferries, rafts, and floating bridges. Mines and shells wrecked British vehicles and blocked routes. The engineers tried to shield the bridgeheads with smoke, but the wind blew the wrong way, and the Bailey bridges had to be abandoned.

The Texas National Guard

The 46th Division’s attempt to cross the Garigliano and take pressure off the central V Army attack had failed. Maj. Gen. Fred Walker’s 36th Infantry Division would have no cover.

The 46th Division’s commander, Maj. Gen. J.L.T. “Ginger” Hawkesworth, went to Walker to apologize for the failure, offering to provide one of his battalions to support the 36th attack, but the American was unimpressed. “The British are the world’s greatest diplomats,” Walker wrote in his diary. “But you can’t count on them for anything but words.”

The 36th Infantry Division was a proud outfit of Texas National Guardsmen, with traditions that dated back to the American Civil War. Walker was a quiet, rangy, and rugged veteran of the Mexican Expedition of 1916 and World War I. In person he was shy and sensitive, and ill at ease with West Pointers. Still, he had turned the division—a peacetime social club for well-connected Texans—into a tough fighting division.

The 36th fought its first battle at Salerno, a harsh trial for any division. Two battalions of 1,000 men had been wiped out: one surrounded and captured, the other ambushed by artillery. The assistant division commander collapsed under the strain and was replaced by Brig. Gen. William Wilbur, a flamboyant and blunt officer.

The 36th had slogged up the Italian peninsula since then, its men feeling they were in a hard-luck outfit that always got the dirty deal. That was common in a lot of front-line units, but 2nd Corps deputy chief of staff, Colonel Robert Porter, wrote that the division had never really found itself.

Nor did General Walker get along with his two bosses, Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Keyes, who commanded the II Corps, or Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark, who commanded the Fifth Army. Where Walker was shy and retiring, Clark was an outspoken, brash self-promoter. Keyes was a cavalryman, daring and impulsive in planning and action, but restless and flighty. Walker was older than both of his superiors and increasingly at odds with them.

Where Keyes and Clark relied on naval gunfire and heavy artillery to flatten towns and German morale, Walker believed they had little impact on well-defended German positions and too much impact on defenseless civilians.

Now, as the 36th moved up to the Rapido River, Walker was even more worried—the troops entered the line in mid-November amid pouring rain. Temperatures fell to freezing. Everyone froze in soaked clothing. Jeeps bogged down in the mud. Walker requisitioned 12,000 winter jackets, 6,000 pairs of leather gloves, and 2,000 gasoline heaters for his men, but it was not enough. Even so, he kept going to the front, ignoring visitors, to check on his men.

“A Tactical Monstrosity”

The big question was whether the 36th could cross the Rapido with the Germans in possession of the Cassino Monastery Hill, which dominated the whole waterlogged plain. Walker believed a frontal assault would be a disaster. The river and the German defenses reminded him of World War I battles where he had held the Marne River line with a small force against vast but doomed German attacks. But Walker kept his protests mild, and Keyes and Clark ordered him to get on with the assault.

Now, with the failure of the 46th Division to cross the river, Walker realized his division’s going would be harder. McCreery recommended the attack be canceled. He did not think it would succeed even if the 46th had taken its objectives, calling the whole Rapido attack “a tactical monstrosity.”

Ironically, Clark’s purpose had already been achieved. The British attack had brought in Kesselring’s reserves on the Garigliano. But that was immaterial to the men of the 36th Infantry who faced the Rapido River. Its banks were steep and vertical, between three and six feet high, between 25 and 60 feet apart. The river was nine to 12 feet deep.

The center point of the German defenses was the village of Sant’ Angelo, whose pulverized buildings had been turned into blockhouses, dugouts, bunkers, and trenches, all festooned with barbed wire, booby traps, and mines. The men defending the positions came from Maj. Gen. Eberhard Rodt’s tough 15th Panzergrenadier Division, which was considered one of the finest German outfits in Italy.

Walker’s engineer, Lt. Col. Oran C. Stovall, flew over the river, making a personal reconnaissance of the area, and he reported to Walker: “First, it would be impossible for us to get across the river. Second, we couldn’t cross, and third, if we got across the river there was no place to go.” The Liri just seemed a muddy bottleneck.

There was another problem. While engineers could remove mines and mark out safe routes, the Germans had an irritating habit of sending patrols across the river to move the tapes or plant new mines.

The Plan to Cross the Rapido

With Monte Cassino looking down on the valley, the only way Walker could neutralize the German height advantage was a night attack. He proposed a thunderous 30-minute barrage on the evening of January 20, followed by two regiments moving to the river at 8 pm. The 142nd Infantry Regiment would cross north of Sant’ Angelo and the 143rd to the south, grabbing the village in a vise. The 141st Infantry Regiment would be Walker’s reserve for exploitation.

It was up to Stovall and his men to get the 36th across the river. He spent three days studying the terrain, interrogating local civilians, and locating equipment. There was not enough, not even a standard M-1938 footbridge. Stovall would have to make do with sections of catwalk laid across pneumatic floats, 24-man rubber dinghies, and 12-man plywood scows. The 111th Engineer Battalion and two companies of the 16th Armored Engineers were assigned to clear mines and maintain routes leading to the bridges and exits on the far side. Once the riverbanks were free of enemy fire, they would build Bailey and treadway bridges across the Rapido. The 19th Engineer Regiment would provide a battalion to each assault regiment, each equipped with 30 rubber reconnaissance boats, 20 wood assault boats, and four improvised footbridges. The engineers had more than 100 boats. Crossing the Rapido would be an exercise in paddling and assembling cable ferries and bridges.

To make matters worse, no roads to the crossing sites were capable of carrying the trucks that would haul the boats to the water. The assault troops would have to manhandle the boats across the flooded ground to the river. Because of the loss of 40 DUKWs before Anzio, there were none to spare for the 36th crossing.

Walker swapped out the assignments of the 142nd and 141st Regiments in his battle plan to equalize the amount of combat the regiments were seeing. Then he changed the crossing sites for Colonel William H. Martin’s 143rd Infantry Regiment, which astonished Major Jack Berry, commander of the 1st Battalion, 19th Engineers. There just seemed to be no teamwork in the planning. The two engineer battalions had never worked with the 36th before.

Lieutenant Colonel Aaron A. Wyatt Jr.’s 141st planned to cross the river with its 1st Battalion at one site, seize a bridgehead, and then send over the 2nd and 3rd Battalions. The 143rd planned to send over its 1st and 3rd Battalions at two points. With the plans in hand, the officers briefed their men. They had no illusions the attack would be easy. Both regiments were short 500 men, and many of the GIs who shouldered their M-1 rifles and grabbed an extra bandolier of ammunition were fresh from replacement depots and new to combat. Staff Sergeant W. Kirby of the 3rd/143rd believed the Germans had an “ideal position.” Technical Sergeant C.R. Rummel, of the same outfit, said, “We thought it was a losing proposition, but there ain’t no way you could back out.”

The Nighttime Strike

On the night of the 19th, the assault battalions moved off Monte Trocchio and through clumps of trees to their starting points. Meanwhile, the engineers, unable to move their bridges up to the river by vehicle because of the sodden ground, deployed the bridges in two dumps, one for each assaulting regiment. Infantrymen would carry the bridges to the water and place them in the river. Engineers would supervise the assembly.

Amid darkness and fog, the 1st Battalion of the 141st Regiment moved to attack. The boats had been laid out for them by the engineers, but when the infantry found them, several had already been smashed by German shellfire. The troops headed off to attack at 7 pm, plodding the 200 to 300 yards from the boat depots to the river. Half an hour later, 16 battalions of American artillery and mortars opened up in a barrage. German guns roared back, and the darkness was lit by exploding shells, which illuminated attackers. One German shell cut down 30 men.

Among the men advancing with 1st/141st was a young lieutenant from Grand Rapids, Michigan, named Carl Strom. A high school ROTC and college man, he was assigned to B Company of the 1st/141st on New Year’s Day. Seven of B Company’s officers were, like him, brand-new replacements. After a week of fighting, he was given command of 3rd Platoon. Half of the men were also fresh from training. Aware of his own inexperience, Strom told his platoon sergeant and squad leaders to be honest with him. “You guys know more about this than I do even with all my training. I can’t match what you’ve learned in three or four days of combat.”

Another leader, Lieutenant Bill Everett of Baltimore, commanding C Company’s mortar section, tried to inspire his men. He told them that night they “were going to pay their dues for being an American.”

Now Strom and his other platoon leaders drew cards to see who would lead the attack. Strom drew the high card, so his platoon set off at 6 pm, bayonets fixed, behind an engineer guide who took the wrong path, which led Strom and his platoon to the battalion’s forward command post. They tried again, but the noisy turnaround attracted German fire.

Keeping the River Crossing Open

Despite the flash of shells, it was hard for the Americans to see the marker tapes in the dark. German shelling destroyed the tapes or buried them in the mud. To avoid shellfire, Strom’s men dived into mud and set off more mines. By 8 pm, when the Americans were scheduled to cross the river, they were still struggling to reach it, and one-fourth of their 400-pound boats and bridges had been destroyed, damaged, or abandoned, hurled down by wounded men who found them too heavy to carry. It took six to eight men to carry one boat.

By the time the 1st/141st reached the crossing sites, half the bridges were useless or abandoned. Lt. Col. D.S. Nero, who commanded the engineers, already saw the mistakes: the troops had to carry the boats more than 200 yards from depot to river (the assault troops should not have had to carry their own boats, as it exhausted them), there were too few crossing points, too many troops were bunched too tightly, men got lost in the fog, and abandoned boats and bridges lay where they fell, blocking approach routes.

Strom’s platoon was in the thick of the shelling and the men shuffled down a sunken road to their crossing point. “The Germans had these places all zeroed in for their artillery so they could fire blind,” he said later. “We were about halfway down the sunken road … I was up front with my runner and an engineer guide and I was probably 300 feet ahead of the company. As I turned around to look back, two German shells came in and they hit right in my platoon. They killed or wounded every man.” B Company’s commander was dead, too, along with his exec. Three officers were left, none of whom had been in combat, and the senior man (over Strom by two weeks) took command.

Under heavy fire, about 100 Americans managed to paddle their boats across the river and stake out a small claim. When the engineers started assembling their footbridges, they found one had been wrecked by mines and a second was defective; German shells blasted the remaining two apart while they were being assembled. The engineers scrambled around, put together the parts, and managed to build a single structure that opened for business at 4 am. Infantrymen of the 3rd/141st struggled across the soaked and shaky bridge. The shelling was too heavy for the engineers to build the bridge for vehicles.

Strom finally got over the river on a footbridge around 4 am, and he and his men found mines, booby traps, barbed wire, and machine-gun fire from a position 250 yards away. They tried to dig in, but first had to probe for mines with their bayonets. Then they found that in the damp earth their foxholes filled up with water to their waists or just collapsed.

The bridges were in terrible shape, but so were communications. By dawn, German shells knocked out the phone wires to the far bank. All the radios were lost or damaged, so the only way the Americans on the near bank could tell U.S. positions from German was by the roar of machine guns. The German MG-42 had that distinctive buzzsaw sound from its high rate of fire.

With dawn breaking, Wilbur, the assistant division commander, was on the scene to assess the situation. There seemed little point in continuing the attack, with one footbridge and only a few boats, so he ordered the men on the near bank to retire to their assembly areas before daylight brought down precise German shellfire and tanks. The men on the far shore were told by a messenger to dig in and hold until relieved.

Withdrawing by Daylight

Meanwhile, Major David Frazior’s 1st Battalion of the 143rd Regiment launched its attack south of Sant’ Angelo. They had an easier time at first. At 8 pm, a 40-man platoon launched assault boats and crossed the river. After unloading, the engineers paddled the boats back—and then the Germans opened fire, blasting open all the boats and sinking them. The engineers tried to build a bridge across the river. By 8:20 it was done, but minutes later, German guns destroyed it.

By 11 pm, Colonel W.H. Martin, commander of the 143rd, came to the scene and found Frazior trying to push more boats to the river. Personally pulling an engineer lieutenant and 18 of his men out of foxholes, Martin urged the attack forward. Through leadership and determination, the Americans pushed a battalion and two bridges across the Rapido by 5 am. Shortly after that, German shells destroyed one bridge and gravely damaged the other—the Americans could cross it only one at a time.

On the far shore, the 1st/143rd came under fierce counterattacks from the 15th Panzergrenadiers. By 7 am, the Americans were being forced into a pocket against the river. Frazior asked Martin for permission to withdraw, and Martin passed the request up to Walker. The division commander ordered Frazior to hold his ground and await reinforcement.

The message came too late. Frazior’s men were facing German tanks and broad daylight. On his own initiative, he began withdrawing his troops. By 10 am, the survivors of his battalion were back across the Rapido.

“A Few Boats and One Footbridge”

At the 143rd’s other crossing site, the 3rd Battalion and its engineer guides got lost in darkness and fog and wandered into a minefield, which shattered men and boats alike. Disorganization reigned after that, and by 11 pm, when order had been restored, all the rubber boats assigned to the battalion had been destroyed by German shelling and mines. Infantrymen waited for the engineers to arrive with wooden boats to replace the rubber ones, while engineers waited for the firing to die down before building bridges. Both groups waited until after midnight, when Martin phoned to ask what was going on.

Major Louis H. Ressijac, who commanded the 3rd Battalion, said, “We have a few boats and one footbridge, but we don’t know the way through the mine field. Am looking for an engineer guide.” Ressijac promised to attack in an hour. But at 1 am, there was still no progress, nor at 3 am and at 5 am, Martin relieved Ressijac of command and sent Lt. Col. Paul D. Carter to fire up the attack. By the time Carter reached the crossing sites, dawn was breaking. Not one man of the 3rd Battalion crossed the Rapido. Gloomy, Carter had the men withdraw to their assembly areas before sunrise.

Meanwhile, Strom and his men of the 1st/141st were still clinging to their position on the far bank north of Sant’ Angelo. After sunrise, Strom peered up from his flooded foxhole to see what was going on. A bullet bounced off the side of his helmet. His foxhole mate was not so lucky—the German bullet hit him right between the eyes. After that, Strom could only take cover from intermittent German shelling. Walker was upset. He wrote in his diary, “I told Col. Martin that he would have to put more of the will to fight in his troops. He said that he would do so. Maybe he will—I doubt it.”

A Failure to Coordinate

Now came time for analysis and recrimination. The British 46th Division had let down the Texans. Had their crossing been successful, they would have held the high ground that enabled German artillery spotters to call down accurate fire on the 36th. The Americans lacked experience and confidence for night fighting. The engineers and infantry were not well coordinated. Leadership was weak, mostly because so many young officers were replacements, as were the sergeants.

Meanwhile, Walker and his staff, having finished their postmortems, discussed what to do next. U.S. troops were still on the far side of the Rapido. A rescue or reinforcement operation had to be launched. But when? Wyatt and Martin believed a daylight attack was out of the question.

At a 9:45 am staff meeting with his subordinates, Martin blamed the engineers for not providing enough boats or guides to lead his infantrymen to the river. Martin asked the exhausted Berry how many boats and bridges he had left. Berry reported 17 bridges left and 72 pneumatic boats his men would pump up, promising they would be organized “some way.”

Another problem was that a large number of men had gotten lost in the darkness and fog, leading to an inordinate number of stragglers. Some were genuinely lost, others were genuinely scared. Martin told his bedraggled officers, “You gentlemen must realize this operation is a vital operation and I trust you have been in the army long enough [to know] that you can accomplish any mission assigned to you. It should have been proven last night.” The river, he was implying, was supposed to have been crossed.

But at the Fifth Army’s tactical headquarters, Clark was getting a different picture of events. Reports to him suggested that the British X Corps and U.S. II Corps were advancing. Ready to embark for Anzio, Clark phoned Keyes and urged him to “bend every effort to get tanks and tank destroyers across the Rapido promptly.”

Keyes drove to the 36th Division’s forward command post and got there at 10 am, to pass on Clark’s desires. Lecturing the divisional commander, Keyes said that if tanks had been rushed over the previous night, the assault would have been a success. A noon attack would have put the sun in the Germans’ eyes.

Walker said he could not attack again by day. He would try again at 9 pm. For Keyes, that was too long to wait. He wanted it to go in at once, but certainly before 9 pm.

Walker pointed out that his infantrymen needed to reorganize and his engineers needed to get new equipment. Keyes was unimpressed. Commanders were supposed to overcome obstacles, not be overcome by them.

50 Plywood Boats, 50 Rubber Crafts

Walker phoned his senior officers and reported back to Keyes that the earliest he could attack would be 2 pm. The engineers promised 50 plywood assault boats and 50 rubber craft in the division area by 12:30, which would give the assault troops an hour and a half to pick them up and move out. Not good enough for Keyes, but he would have to accept it. Keyes drove off, and Walker wrote in his diary, “I expect this attack to be a fizzle just as was the one last night.”

But communications were still snarled. Martin did not know he was going in until 1:10 pm, 50 minutes before jump-off. He asked for more time and was allowed to postpone the attack until 3 pm. Wyatt’s boats weren’t delivered in time either, so he got the same one-hour delay. But at 3 pm, the battalion commanders were objecting, the men were exhausted, and the boats still had not arrived. A 4 pm attack seemed more reasonable. Walker agreed.

At 3:30, Martin phoned Walker to say some of the boats had arrived, but not all. Berry saw one truck being driven by a brigadier general. Martin asked for another delay. This time, Walker said no. Martin was to go with what he had. At 3:45, with 15 minutes to go, Wyatt learned his boats had been on hand for an hour. But it was too late to meet the 4 pm deadline, so Wyatt asked to hold off until 9 pm. Wyatt got his wish. Martin still had to go in even though the only real reason to attack was to save the men on the far bank, and there were none in his sector.

At 4 pm, Martin tried again. The assault troops filed in at the same crossing points. Martin figured that, while the Germans would have the sites mapped and referenced, his men would not lose their way finding them a second time. And he also laid down a heavy smoke barrage that created an artificial fog on the river and nearly suffocated his own men—a small price to pay to avoid being shelled.

The companies pushed off in rubber boats, and for two hours paddled back and forth, putting all three companies of the 3rd/143rd on the far shore by 6:30 pm. Then the heavy weapons companies came over with their machine guns, while the engineers built footbridges. With those up, the rest of the battalion, including its headquarters, shuffled across the river.

Martin then sent a second battalion across, while the third battalion guarded the crossing site and kept the bridge open. By 2 am on the 22nd, the morning of the Anzio landing, Martin had a bridgehead. His men moved 500 yards inland, came under heavy fire, and dug in to consolidate their gains.

Building a Bailey Bridge Under Fire

Now the engineers had to replace the footbridges with treadway and Bailey bridges capable of supporting M-4 Sherman tanks. Normally, engineers could lap up a pontoon bridge in 45 minutes, but with the steep Rapido banks, they had to cut approaches.

Bailey bridges, a British invention still used around the world today, looked then as now like giant Erector sets, made of prefabricated sections in standard lengths, put together with rivets. They took six to eight hours to build, and were generally built out of range of enemy fire. This night they would be built under heavy fire.

But the pontoon bridges and Bailey equipment had not been brought forward yet. Time before the Shingle landings and dawn was running out. Keyes himself ordered that a span-type Bailey be flung across the river from one bank to the other, obviating the need for approach ditches. The engineers were astonished at the idea: the whole area was under fire. The engineers were brave enough, but this looked like suicide.

Suicide or not, the engineers tried. By midnight, they had cleared the mines on the approach routes, and trucks struggled forward through the quagmire to deliver the bridges. The trucks got stuck. The engineers hauled the steel sections to the site by hand and tried to start work, but German fire was too heavy. The engineers spent most of their time trying to take cover. By 9 am, it was clear that the bridges would not get built.

Eight Hours, No Progress

Meanwhile, Martin’s second attack, by the 2nd Battalion, went in on schedule. By 6:30, two companies were over the river, but the German shelling became fierce. Until 10:30, nothing could move across the river. Frazior personally crossed the footbridge to get his men moving, but it was impossible. German resistance was too strong. At 1:30 am, he nonchalantly radioed Martin, “I had a couple of fingers shot off,” and said he would stay there until a replacement, Lt. Col. Michael A. Meath, arrived. It took Martin three and a half hours to send forward a replacement for his wounded subordinate.

Three officers and 140 enlisted men made up F Company. By day’s end, all the officers were wounded, and only 15 of the enlisted men, many also wounded, made it back across the Rapido. Engineers began building a Bailey bridge at 3 am, but after four hours of work, it was only 4 percent completed. By 5 am, all three rifle company commanders were wounded, the footbridge was destroyed, and the boats were all wrecked. The engineers spent an hour and a half laying down two new footbridges, but all they were doing was helping litter bearers haul wounded men to the rear—or stragglers to flee, claiming illness or that they were carrying a message. By dawn, Meath reported he had only 250 effectives. And trucks bringing new bridges were stuck in the mud. Berry reported his Bailey bridge would be ready—if there was no enemy fire or interference—at 3 pm.

Martin told Berry to build the bridge, regardless of enemy fire. Martin would get more smoke pots to cover the construction efforts. But by mid-morning, the Bailey program was stalled. Engineers were trapped in foxholes, scared and shelled, a mile from the bridge site. Officers moved the engineers to the bridge site, but everyone was reluctant to go—the situation was getting hopeless. At noon, Martin saw that his bridgehead was untenable, and he ordered his men to withdraw.

Meanwhile, Wyatt’s 141st Regiment launched its attack at 9 pm on January 21, at the previous crossing site. The new boats the engineers brought forward were found to be defective, thanks to German shellfire, so only 60 men could brave the river and reach the far shore. In five hours of maneuver and attack, the 141st eliminated the German riflemen and machine guns. That gave the engineers time to build bridges. By 2 am, the engineers had two improvised footbridges finished, and two battalions headed across the river by dawn, along with their heavy weapons teams. The Americans moved 1,000 yards inland, despite heavy casualties, then dug in. But they found no sign of the men who had been trapped on the far bank.

While the infantrymen consolidated their gains, the engineers turned to building a Bailey bridge, hauling the girders and frames by muscle power across the swampy ground and shell holes. They started at 1 am and eight hours later had made no progress.

“The Stupidity of the Higher Command”

Everybody in the 36th was getting hammered. Around 4 am, the Germans hurled 300 shells at the division’s command post, causing casualties and disrupting the division’s staff work. Rumors spread that the Germans were counterattacking and making their own river crossing to trap the Americans. They were not, but heavy river currents washed away two footbridges weakened by German shells. The men of the 36th were tired, wounded, lost, and hungry. By 4 pm, every commander in both battalions on the far shore was dead or wounded, and a German shell hit the last footbridge, obliterating it.

Between 6 pm and 7 pm, 40 men paddled their way to the near bank, clinging to logs and debris to propel themselves through the bitterly cold current. Everyone else on the other side was left to be killed or captured. After about 8 pm, the sounds of gunfire died down on the far side. The 1st/141st was annihilated. The 36th Division suffered more than 430 killed, 600 wounded, and 875 missing. Most of the missing were presumed killed or captured. One company commander reported that out of 184 men in his outfit, only 17 were left. “My fine division is wrecked,” Walker wrote. The 15th Panzergrenadiers lost 64 killed and 179 wounded.

Walker further wrote, “The great losses of fine young men during the attempts to cross the Rapido River to no purpose and in violation of good infantry tactics are very depressing. All chargeable to the stupidity of the higher command.”

The postmortems continued. The attack was badly prepared—four battalions carrying heavy assault boats ac6.

British Guardsmen vs German Grenadiers

The 29th hit the British 56th and 5th Divisions on January 21, just as the British attack was wrapping up. The Germans stopped the British cold. The British were weary and short of men. Private S.C. Brooks of the 6th Cheshires saw that his platoon was made up of replacements with nine months of service. Engineer Matthew Salmon, working on a ferry, saw that his passengers were edgy, saying, “How much longer are we going to be here? It’s about time we were bloody relieved.”

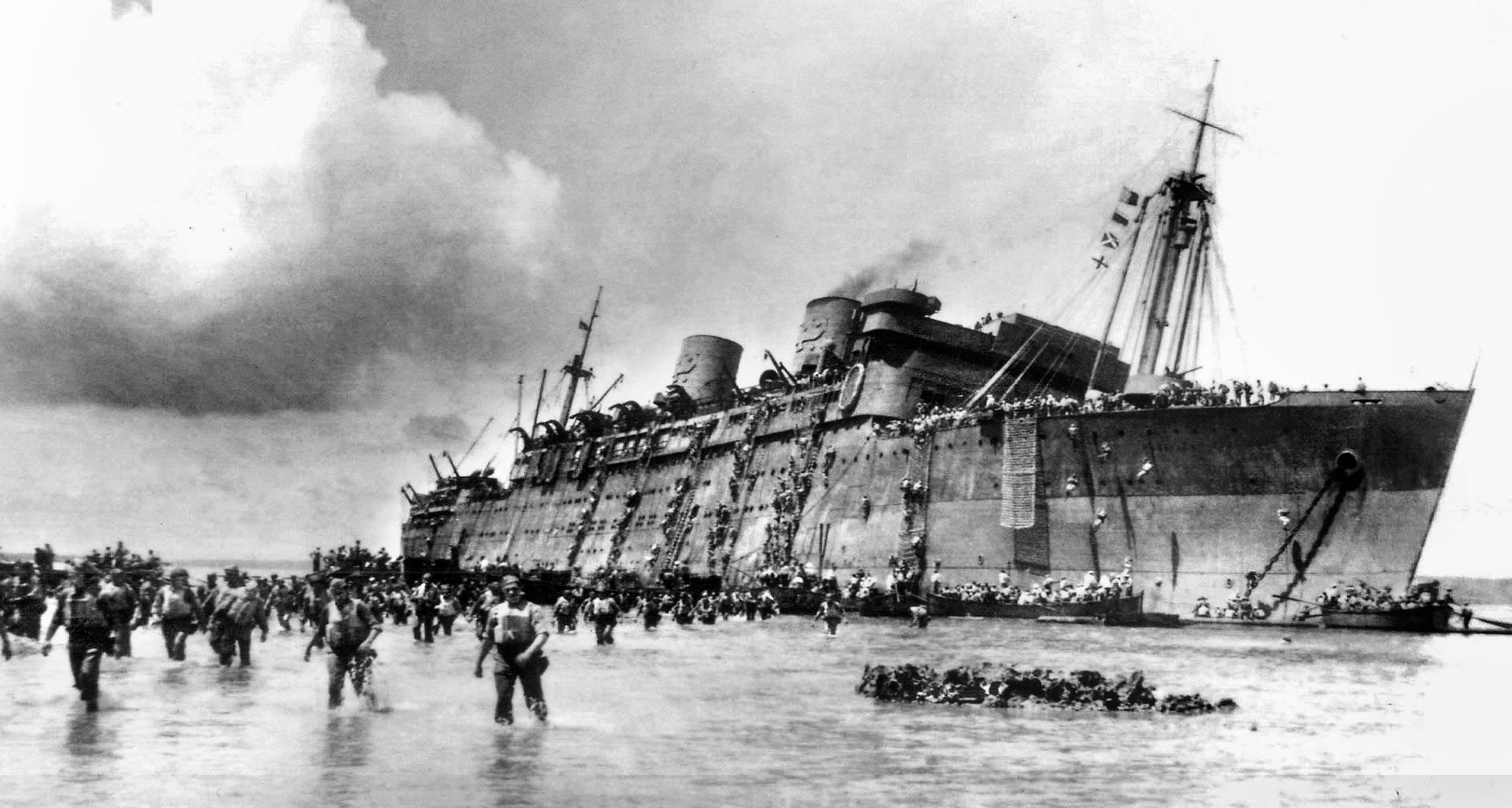

The next morning, the 22nd, the Anzio assault went in. The Anglo-American VI Corps enjoyed complete surprise, but the Germans reacted with their usual speed, rounding up a variety of units to contain the assault. None of them came from the Garigliano and Rapido battles. The Fifth Army’s river assaults had failed in their primary purpose—to draw off the German defenders.

The next six days saw hard fighting along the Garigliano River. The British launched attacks with ample determination against equally determined counterattacks. The 5th Division’s 15th Brigade pushed through an attack to find the Germans charging back, shouting, “Give up, Tommy, you are surrounded.”

With the 5th Division’s attack running out of steam, the British sent in the crack 201st Guards Brigade against the 90th Panzergrenadiers, and guardsmen and grenadiers traded verbal insults amid the vicious fighting.

The fighting raged on for the hills and mountains, with the Green Howards reaching Minturno, and Hill 201 changing hands four times before the British took it for good. The 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers tried to take Monte Natale but were not successful until January 29, when two battalions of the 17th Brigade took the crest. By then, the 5th Division was completely shot out.

“The Enemy Remains Firm”

The 56th Division was not doing any better. By the 20th, all of its brigades were committed, and two were tired and low in strength. Troops could only move by night. On the 24th, McCreery had to admit “the enemy remains firm … 56 Division troops have now been fighting for seven days and are tired. No further advance can be expected on the Corps front for some days unless the enemy withdraws.” Two companies were down to three officers and 37 men between them.

McCreery sent in the 43rd Royal Marine Commando and 9th Army Commando Battalions to make progress up Monte Ornito, and the tough men in the green berets gained ground. But there were not enough reserves to exploit the success. The overall picture was slow going. The supply situation was a mess— the 10th Royal Berkshires went in without blankets or greatcoats, and the trails were impassible to mules. Porters had to bring everything up. Private George Pringle of the 175th Pioneer Regiment took supplies from pioneer mule transport companies and carried packs weighing up to 50 pounds on his back.

On January 23, the 1st London Scottish and 10th Royal Berkshires made a failed attack on Monte Damiano. The British sent up medics under Red Cross flags to recover the wounded. To the Britons’ surprise, a German officer appeared atop the ridge and said in English, “Gentlemen, will you please stop firing while we bring in our wounded.” A cease-fire lasted long enough to bring the wounded men down on both sides.

On January 29, the X Corps made one more attempt to take Monte Damiano, with the 2nd and 1st/4th Hampshires leading off, having recovered from their failed Garigliano crossing. The 2nd Hampshires’ diary said it all: “Attack unsuccessful owing to unexpected nature of ground and excessive use of grenades by the enemy.” The follow-up attack was called off. Everywhere the British tried to attack, they found ferocious German resistance.

McCreery decided to hit the Germans across the mountains by infiltrating from behind, and that worked. The German defenders of Castelforte were extremely surprised, but the British troops struggled atop windswept mountains, some 2,000 feet high, under heavy shelling.

On February 10, McCreery faced facts. His men had taken Minturno and gained a few bridgeheads across the Garigliano, but had not driven the Germans off the pinnacles. The corps went over to “active defense” and counted the dead and wounded. Nobody was sure about German losses, but the British had taken a beating. The 2nd/6th Queens had lost 138 men, 28.6 percent of its strength. The 7th Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Infantry lost 188 men, 37.8 percent of its strength.

“A Beached Whale”

Despite fatigue, wintry weather, flooded terrain, high mountains, and higher casualties, Clark had to continue the offensive. About 70,000 British and American troops and 356 tanks were trapped at Anzio. Churchill, who had pushed for the operation, was enraged. He had hoped “we were hurling a wildcat on the shore, but all we got was a beached whale.”

With the Germans hammering at the Anzio beachhead, Fifth Army now had to charge to its rescue as soon as possible. Clark could not wait for spring and dry weather. But he was running out of fresh troops. All that was left was the 34th Infantry “Red Bull” Division, holding the ground between the battered 36th at Sant’ Angelo and the equally worn-down French Corps on the Cassino Massif. The 34th was facing the town of Cassino and the monastery brooding above it. The division’s time had come.

Clark’s plan was to send the 36th Division’s 168th Regiment along the far side of the Rapido River north of the town in one thrust and send a second dagger directly across the Cassino Massif, three miles behind the river, and into the Liri Valley. The French Corps, despite fatigue, would attack again, this time on the far right, toward Colle Belvedere, to protect the American right flank.

The Red Bulls’ 133rd Infantry Regiment would be the inner wheel. It would have to take an old wrecked Italian Army barracks two miles north of Cassino, while the 168th drove on a hillock called Hill 213, a stepping-stone to the higher peaks that led to the monastery.

Under Maj. Gen. Charles W. “Doc” Ryder, the Red Bulls would have to attack across a river less formidable than the 36th faced at Sant’ Angelo, but they would still face soggy ground. More important, the Germans created a 300-yard-deep mine belt on the far shore, in front of a flat plain, cut clean of all vegetation, which provided German machine-gun nests, strongpoints, and pillboxes with perfect fields of fire. Barbed wire obstacles stood six feet in depth. All the surviving buildings had been turned into pillboxes, with self-propelled guns and antitank guns poking out from them, and the hill that led to Hill 213 was surrounded by 150 yards of barbed wire.

Senger, the literate Rhodes Scholar and lay Benedictine, trained his men on how to dig into rocky positions with crowbars and explosives instead of spades. His troops learned how a single man could lower a wounded soldier with ropes and haul him on an improvised sled. It was a remarkable adaptation to difficult conditions, and it was a hallmark of the German army throughout the war.

Three Battalions on the Beachhead

The slopes of Colle Maiola, Monte Castellone, and Monte Cairo rose 450 meters in a distance of 1,000 meters and were crisscrossed with wire, mines, felled trees, bunkers, and machine-gun emplacements. Atop the pinnacles of Colle Sant Angelo, Hill 444, and Hills 593/569, the Germans had built sniper posts and mortar emplacements, all covered with thick logs. The mortars were neatly concealed in gullies.

Nor were the defenders any slouches. This part of the Gustav Line was held by elements of the 71st Infantry, 5th Mountain, and the 44th “Hoch und Deutschmeister” Infantry Divisions, under Lt. Gen. Dr. Franz Bayer. The original 44th was based on the historic Austrian 4th Infantry Regiment and been destroyed at Stalingrad. A new 44th was created to replace the old one, and the Austrians were determined to uphold their long traditions. Even so, the Austrians were understrength.

On the evening of January 24, backed by tanks, the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 133rd Regiment attacked the German defenses. With the regiment’s 2nd Battalion still back in North Africa, the 100th Infantry Battalion, composed of Japanese-Americans from Hawaii, was committed to this, its first battle.

The 133rd immediately ran into the minefield. The tanks hurled more than 1,000 75mm shells into the high far bank of the river to break it down, but with no success. By midnight the following day, the 3rd/133rd was the only battalion across the river, holding a shallow bridgehead. The 1st/133rd found its stream unfordable. All day the 133rd struggled to cross the river, and by midnight all three battalions were across.

From a Withdrawal to a Rout

On the 26th, Ryder sent in troops and tanks to reinforce the bridgehead, but the lead tanks became bogged down in the flooded quagmire, blocking the advance for the remaining vehicles. The 100th Battalion’s attacks were repulsed. The 1st/133rd was forced back across its start line. More than 300 casualties were suffered, and the regiment’s morale was sinking fast. But the attack had to go on. Ryder committed the 168th Regiment, which had been his exploitation reserve.

Early on January 27, the 168th launched its attack, slightly upriver, with a platoon of tanks from the 756th Tank Battalion leading the 1st and 3rd battalions. Most of the tanks slid into the bogs, but four of them were able to make it to the far shore, followed by infantry. All four were out of action from antitank fire, mines, and artillery by 1 pm, but they did their job, as the 168th reached the base of Hill 213 early on the 28th. Unbelievably, the commander of the lead company decided his position was untenable by daylight and ordered a withdrawal to the river. “As he did so,” Martin Blumenson wrote in the U.S. Army’s official history, “the withdrawal turned into an uncontrollable rout. The troops fled across the river.”

The panic spread, and other companies began fleeing. Once the withdrawals were checked, the 3rd/168th regrouped and headed 500 yards north to another crossing point, where they went over again, this time advancing a mile toward the village of Caira. This crossing point proved workable. While the infantry dug in for the night, engineers built “corduroy” roads of logs and tree trunks to enable the tanks of the 756th and 760th Battalions to cross the swampy ground for a new three-battalion attack on the 29th.

“It is a Matter of Honor”

Meanwhile, the French prepared their second attack. Juin briefed Monsabert on the plan, but the 3rd Algerian Division’s commander objected. Juin did not like the plan, either. He was expected to hit one of the least accessible parts of the Gustav Line. The defenses included the 1,669-meter-high Monte Cairo, higher than the monastery, and the 800-meter high Colle Belvedere, all under German artillery observation from Monte Cifalco, a 947-foot pinnacle. Juin wanted to take Monte Cifalco and sweep across the mountains, taking the Gustav Line and the Cassino Massif from behind. Instead, he was ordered into a frontal assault on the massif. Nevertheless, Juin was determined to succeed. He had to demonstrate the French Expeditionary Corps’ loyalty to the Allied cause. “It is a matter of honor,” he told Monsabert. That was all Monsabert needed.

The 3rd Algerian’s Tunisian regiments were tapped to lead the attack. Lacking mules, the Tirailleurs hiked for eight hours through the mountains carrying their supplies to the forward positions. Each man stolidly followed a white patch tied to the pack of the man in front of him. Sergeant Rene Martin of the 4th Tunisian Regiment’s 3rd Battalion led his mortar section across the Secco River, and everybody was soaked through before they could attack. Men also had to wade across the ice-cold Rapido, through water up to their armpits.

The 3rd Battalion’s commanding officer, Commandant Gandoët, wrote, “The battalion is physically and mentally ready. Ready to lead a bayonet charge, to be killed on the mountainside, to deal the enemy all sorts of blows.” The 3rd/4th Tunisian was assigned to capture Hill 470 and then push on to take the high ground, Hill 862, on the northern end of the Belvedere/Abate escarpment. The axis of attack would be “Gandoët Ravine,” which would give the Tunisians cover from shellfire and the advantage of surprise.

The 2nd/4th Tunisian, under Commandant Berne, was to grab the southern end of Colle Belvedere and hit Colle Abate. The 1st/4th Tunisian was the regimental reserve for exploitation.

“Cruel Necessity”

The French attacked at 7 am on January 25. They found the defending Germans as ferocious as ever. The French stormed their way through to the summit of Hill 470 against massive counterattacks. Captain Denee, commanding the 3rd/4th Tunisian’s 9th Company, was wounded in the chest. He crawled to his radio operator and whispered into the mike and to Gandoët: “Denee here … I’m wounded … about to take the objective … I’m handing over command to Lt. El Hadi. Terribly difficult. Don’t worry, the 9th will make it … they’ll make it … to the bitter end.” El Hadi, a Tunisian, leaped to his feet and led his men up the crest.

The 9th Company reached the top, was thrown back by a counterattack, and attacked again. El Hadi had his forearm sliced off by a shell, but he fought on, dragging his arm behind him, the men following, until he was hit by a machine-gun bullet atop Hill 470 and died.

With 470 taken, Gandoët pressed the attack. The 3rd/4th Tunisians found “Ravine Gandoët” to be a steeply sloped gorge, blocked by rocky slabs, 2,500 feet high—three times the height of the Eiffel Tower. The Tunisians climbed the mountain walls with their hands, feet, and teeth. They came under German machine-gun fire, so the Tunisians knocked out the German positions with hand grenades. German shellfire commenced at 4 pm, but still the Tunisians climbed the gorge, freezing, exhausted, thirsty, drenched in sweat. Men nearly blacked out from exhaustion.

After the eight-hour climb, the Tunisians reached their objective, Hill 681, atop Colle Belvedere. It turned out to be lightly defended —the Germans did not think anybody could climb the gorge—and the Tunisians made short work of their attack, sweeping forward and killing most of the defenders, setting the rest to flight. At dusk, exhausted, hungry, thirsty, and out of communication with their regiment, the Tunisians dug in atop their objective.

The 2nd/4th Tunisians drove south of Colle Belvedere to Hill 700, and more Tunisians reinforced the weary men atop Belvedere, then pressed on to Hill 862. Without rest, under heavy fire, the Tunisians climbed the mountains all night, finally securing “Le Piton sans Nom” at 2 am.

The French had taken their objectives but were exhausted from the ordeal. Captain Carre, who commanded the 1st Company of the 1st/4th Tunisians, wrote, “Night black, visibility zero, we trample over corpses; they’re ours, one with no head, his guts spilling out.” Colonel Roux, commanding the regiment, asked Monsabert for a 24-hour delay on resuming the attack but was told it was “out of the question.” The Germans were reinforcing. If the French delayed, the Germans would strengthen their defenses. “Prepare to attack 862 and 915 without delay,” Monsabert said. Monsabert later added to the transcript of the radio message, “Cruel necessity.”

Hold at All Costs

Now the Germans were truly worried for the first time by the repeated Allied offensives. If the Allies were having supply problems with the mountains, the German situation was worse, exacerbated by Anglo-American air interdiction of roads and railways. But the standard German riposte to an enemy attack was a counterattack, and Senger hurled his Austrian troops against the Frenchmen, driving them back to the Secco River.

Sergeant Rene Martin was just finishing setting up a position for his mortars when a warrant officer suddenly shouted, “Get out, get out, get out.” An entire German regiment was advancing. Martin and his mortarmen retreated, and Gandoët’s troops atop Belvedere found themselves being shot at from all sides. For five days, Martin and one of his sergeants lay in a German foxhole, without water or food, under shellfire. Martin held a tin of peas against his lips to ease the chapping.

On Colle Belvedere, the 11th Company of the 3rd/4th Tunisians hung on all day, out of radio contact for most of it. The only orders they got: hold at all costs. The Germans hurled mortar rounds at the Frenchmen. “We are organizing the position,” the company’s war diary read. “Nobody sleeps. No water.Little to eat. The ration boxes were thrown away during the climb because they were too heavy. We must hang on … we stay where we are.”

That evening, the French reinforced the 1st/3rd Algerians to plug the Secco Valley, while the 3rd/7th Algerians were sent to take over Hill 700. Roux decided to hold off on the attack until the reserves had arrived. At dawn on the 27th, Gandoët’s battalion started out of its ravine, across the Secco, and up the escarpments, under heavy German shelling. The men hauled up machine guns, mortars, shells, radios on their backs, under heavy fire, to reinforce the exhausted 11th Company up on the high ground.

The 2nd and 3rd/4th Tunisians were ordered to attack at 4:30, with Gandoët’s men to hit Hill 862, while the 2nd Battalion attacked Hill 915. Both battalions set off on time and into a hurricane of fire. The commander of the 2nd Battalion was knocked unconscious by a German shell, and his battalion struggled. Roux was determined, and the 5th and 6th Companies attacked again at 9 pm. With only a handful of men left, they took Colle Abate at 2:30 am. Gandoët’s men also took a beating.

After five days of bombardment, the French gunners had the range on the ravines and clefts of Belvedere, and the Germans were short of ammunition and men. The French pulverized Point 862 with artillery, and the infantry attacked in the evening. At 7 pm, Gandoët ordered his men to fix bayonets and storm the crest. The Tunisians charged with gusto and took the pinnacle, holding it against determined counterattacks.

“I Will Hang On!”

On the 26th, Colle Abate finally fell, but the French were running out of men and steam. The French had gone in against two battalions of the 44th Division’s 131st Regiment and another battalion from the 71st Division’s 191st Regiment.

Senger had brought in the third battalion of the 131st, a second from the 191st, and the entire 134th Infantry Regiment as well. He also rounded up some pioneers, two reconnaissance squadrons, and even a Luftwaffe airfield security company to hold the slopes. Senger was told bluntly that despite heavy casualties, there could be no withdrawal from Cassino.

On the 27th, Senger counterattacked, hurling his 2nd/191st at Colle Abate and the 1st and 3rd/134th at Hill 700 and the Secco Valley. By 11 am, the 2nd/4th Tunisians were almost surrounded on Hill 915 and forced to fall back. Berne’s battalion had been almost completely destroyed, and Captain Leoni was killed while directing machine-gun fire with his swagger stick.

Gandoët’s men held on a little longer but were dwindling fast. A runner’s message read, “Noon. Situation very serious. Massive counterattacks everywhere. Enemy infiltration. We need an extra battalion. There is no 2nd Battalion.” Half an hour later, Gandoët pulled his 3rd/4th Tunisians off Colle Abate. The Germans charged after them, seeking to regain Colle Belvedere. The French situation got worse. At Hill 861, Captain Belsuze of 11th Company reported, “The men are collapsing with fatigue. The human mechanism has its limits.”

All afternoon, German shells rained down on the French positions, and the thin lines. The 1st/4th Tunisians moved in to support the defense, and they took a beating. Captain Jean took over the remains of the 10th and 11th Companies and shouted into the radio to battalion, “Above all, do not worry! I will hang on!” Then he ordered a bayonet charge to drive the Germans back. It worked. But Jean took 11 hits from mortar shells and died as he was brought to the aid station.

Short on Supplies

Gandoët’s men lacked food, ammunition, and water. A convoy of 16 mules sent with all three was blasted by the Germans. But the battalion hung on, with the supporting French guns firing until barrels glowed hot, the shells falling nearly on top of French positions, breaking up attacks.

On the morning of the 29th, incredibly, Roux ordered the 1st and 3rd/4th Tunisians to recapture Colle Abate. It seemed an impossible order, but the Algerian forces backing up Roux had secured the Tunisians’ rear, and the 7th Algerians were to attack Hill 700 and take over from battalion commander Colonel Bacque’s battalion. With reinforcements and supplies in hand, Roux went over to the offensive.

At 7 am on the 29th, the French attacked. The 3rd/7th Algerians grabbed Hill 700 in half an hour, but the Germans drove them off at 11 am. Bacque’s battalion could not reach Hill 771 and was driven back to its start line. Gandoët’s men, incredibly, made great progress against the depleted German defenders and once again took Hill 862. The Germans counterattacked anyway, despite their own parlous numbers.

But now Gandoët’s ammunition shortages were to put his battalion at a crisis point. At 7 pm, 26 mules finally reached Colle Belvedere’s lower slopes, along with a fresh company from the 3rd/3rd Algerians.

On the 30th, Bacque’s battalion attacked Hill 771 again and grabbed it momentarily. But the Germans drove the Frenchmen off the pile. Bacque was among the last to retreat. Before he did, according to French historian R. Chambe, he “planted his walking stick in the ground, like a range-marker, at the side of the abandoned mortars, and said to his adjutant, ‘Come. We’ll be back to look for that tomorrow.’” The 3rd/7th Algerians took over for Bacque’s battalion, attacked on the 31st, and regained Hill 771, the abandoned mortars, and Bacque’s walking stick. The 3rd/7th pushed on to take Hill 915 by noon on the 31st.

“The Limit of Human Capabilities”

Gandoët’s men were still clinging to Hill 862, long past the end of most men’s endurance. The 11th Company “had reached the limit of human capabilities. Yet still, on all fours, they dragged the ammunition up to Hill 862.”

By now the Germans simply lacked the troops for another counterattack. On February 13, the 4th Tunisian was relieved by the 3rd Algerian, and Gandoët’s survivors were pulled out, with only 30 percent of the assault company’s men left. On the way down, Gandoët himself was wounded by a flurry of chance shells. Of Martin’s outfit of 38 men, only seven shuffled down the hills, to a warm greeting from Juin.

Juin was proud, but angry. The French troops had taken the high ground, and with reinforcement, he believed, could sweep the defending Germans off the Cassino heights and drive into the Liri Valley. If there were no Allied reserves, why hadn’t the 34th Division gone in at the same time, to draw off German reserves? Unless the 34th got moving, Juin would have to pull his exhausted and exposed men off the Belvedere massif, giving up the hard-won ground.

On the 29th, the 168th Regiment attacked in force across the Rapido, trying to take the high ground in front of Caira, Hills 56 and 213, which were connected by a ridge. It took all morning to get the tanks across the Rapido to support the infantry, pinned down by minefields, machine guns, and barbed wire. By afternoon, a dozen of the 50 promised tanks arrived. The rest were destroyed or bogged down in mud.

The surviving tanks clanked through the minefields, blasting through the antipersonnel mines with no damage to themselves, creating lanes through which the infantrymen could move. The German machine gunners abandoned their positions in the face of the American tanks and retreated.

With the tank support, the 168th grabbed its objectives by dusk and began consolidating. The 168th’s men found that the German concrete bunkers were huge—accommodating up to 30 men in bunks, with plenty of food, ammunition, and even heating. Bolstered by German concrete and ration packs, the 168th held off counterattacks and captured the village of Caira. The German and American troops were so close they could hear each other talking.

“Fighting Was the Bitterest met to Date”

The battle was going well, but it was a tremendous strain on the Red Bulls. More than 1,100 mules and 700 litter bearers were needed. “Fighting was the bitterest met to date; casualties for all causes were high; replacements were slow in arriving and inadequate in number,” Ryder wrote. He intended to continue the attack on the 30th, using his 135th Regiment, since the 133rd was shot out. Keyes was worried, too. Asked to give an estimate of when Cassino would fall, Keyes could not do so.

While the 168th dug in, Senger continued to reinforce his lines. He moved the 211th Regiment of the 71st Infantry Division, another division bearing the number of one annihilated at Stalingrad, to the town of Cassino. The 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 90th Panzergrenadier Division’s 361st Panzergrenadier Regiment, and the division’s colorful commander, Maj. Gen. Ernst Gunther Baade, arrived to take over the defenses on the massif. They were followed by the 3rd Battalion of the 3rd Parachute Regiment from the 1st Parachute Division.

The 90th Division was another outfit that had been rebuilt from a disaster, in this case, North Africa, formed in June 1943 from miscellaneous units in Sardinia. Baade himself had survived the North African campaign. Eccentric in dress, an Anglophile, and prewar international equestrian star, he sometimes wore a kilt over his uniform and carried a bone-handled dagger instead of a pistol.

Against stronger opposition, the 133rd Infantry Regiment attacked the old cavalry barracks, trying to break open the road into the northern end of Cassino. Backed by tanks, the 133rd cleared the barracks on February 1, then fought its way along a mountain shelf between the Cassino Massif and the Rapido River, heading for Hill 175, which overlooked the northern end of Cassino town. Then the 133rd finally stormed into the town itself.

For a week, the 133rd battered at the edge of Cassino, trying to take Castle Hill, a nearly vertical hill that rose 193 meters over the town and was topped by a ruined fort. The 133rd kept trying but made no progress in the ravine between Hill 175 and the castle. While the 133rd struggled in Cassino, the 135th fought its way up the massif from Hill 213. Its job was to drive on the French left and seize the monastery and the mountains beyond. The 135th’s first objectives were Colle Maiola and Monte Castellone.

When the 135th attacked on February 1, its troops moved up in single file in a dense fog, completely concealed from German gunners. As the 135th moved through the mist, its soldiers could hear Germans talking. “We were way up above them and got past in the fog. We could never have done it otherwise,” remembered Don Hoagland of the 3rd/135th. By 10 am, Colle Maiola and Monte Castellone were in American hands, and Hoagland and his buddies were digging foxholes.

Snakehead Ridge

The next day, the Germans counterattacked Castellone, but the rest of the 3rd/135th pushed on toward the monastery along a ridge that would gain the name “Snakeshead Ridge” for its shape. At the end of Snakeshead Ridge stood Monte Calvary, Hill 593 on the Chinagraph maps, a steep-sided hill 2,000 yards from the rear entrance to the monastery. Hill 593 was topped by a ruined fort, which had a perfect view of the massif area.

With the 135th advancing, General Mark Clark was optimistic. “Present indications are that the Cassino heights will be captured very soon,” he wrote to his boss, Field Marshal Sir Harold Alexander on February 2. The next day, the 135th, backed by a battalion from the 168th, advanced from Monte Castellone along Phantom Ridge, parallel to Snakeshead, aiming at Hill 706 and Colle Sant’ Angelo (or Hill 601) beyond that, to complete the effort to cut off the monastery.

The move on Hill 706 went fine, but Baade’s men counterattacked at Colle Maiola against Hoagland and his men, and they tried to dig in. They couldn’t. Beneath the soil was solid rock. The men created small hollows and piled stones around them to create “sangars,” a word that comes from the Hindustani word “sunga,” which describes a rock parapet made by moving loose stones into a wall. The British and Indian Armies had picked up the concept and the term from the Northwest Frontier Province and passed them on to the Americans.

Now the Americans built their sangars and found they worked. The German attack was beaten off. On the following day, the Americans kept moving up Snakeshead to within 200 yards of Hill 593. On the left, the rest of the 135th and 168th Regiments advanced toward Hill 445, directly before the monastery. The 34th was advancing on three axes and was nearly at the Liri Valley. One more push, and the monastery and the Gustav Line would be outflanked. The problem was that the 34th was running out of steam.

Casualties were appalling, with companies down to 30 men. To make up shortages, truck drivers and antitank gunners were turned into infantrymen. But even these desperate measures could not help. The 1st/141st was down to 56 men. The 3rd/141st was down to 75. Two of its companies had 25 men between them. Hauling the wounded men down from the heights was another ordeal. The Red Bulls’ 1,000 doctors and medics were overwhelmed.

Most wounds were caused by shrapnel from mortars, more feared than artillery. Because they could be fired over reverse slopes and from narrow positions, mortars could dispense death and destruction from nearly anywhere, with great accuracy. But the biggest manpower drain was trench foot. Up on the massif, men could not change socks and shoes, were always cold, and soon their toes were looking like sausages in the cold and damp.

The Caves Near the Monastery

The senior American leadership could not see what was going on. Brigadier Howard Kippenberger of the 2nd New Zealand Division, checking on the situation personally, had a better view of it. He reported to his boss, Maj. Gen. Bernard Freyberg, that the 34th Division was worn out, and Freyberg questioned the American commanders about the condition of their troops. With the 34th closing in on the monastery and the Liri Valley, General Clark believed that one more push would drive the Germans off the pinnacles. On February 4, a company from the 1st/135th captured Hill 445, near the top of Monte Cassino’s ridge. South of 445, across a deep ravine full of rocks and thorny bushes, was Monastery Hill.

The next morning, two patrols of that company were sent out to capture the monastery if possible. A platoon of 15 men led by a sergeant worked its way through melted snow and mist toward the huge gray blur ahead of them. They moved down through a gully toward a small stream and found three Germans from an observation post fetching water from the stream. The Americans took the Germans prisoner and sent them back with three guards. The rest of the platoon crossed the stream and started up the slope, finally hitting the blacktopped winding road that led to the monastery. They gazed up at the huge building’s east face.

So far, the monastery, its abbot, monks, and the refugees hiding in it had endured isolation, loss of electrical power, and occasional errant German and Allied shells. The Americans would not let their artillerymen fire on the monastery because of its religious significance and because the Vatican had assured the Allies that they had barred German troops from its precincts with a 300-meter perimeter around it.

Now the Americans found, beneath the immense, brooding monastery, that the Germans had taken advantage of two natural caves within the 300-meter perimeter. One held ammunition and the other was a two-room quarters for troops. The monastery’s abbot, Gregorio Diamare, had repeatedly complained about the troops’ presence, but to no avail.

The Americans surrounded the cave and cut the phone line leading in, and the sergeant ordered the Germans to surrender. One German came out to see what the fuss was, and the Americans captured him. The Americans told him in halting German to order the other Germans to come out. If they did not, the American sergeant would toss his grenades at them.