By R. Thomas Campbell

When Texas seceded from the Union on February 1, 1861, it did not take long for the new Confederate government to realize that the state’s 385-mile coastline was extremely vulnerable to enemy assaults. With most of Texas’s newly raised troops shipped off to Virginia, where the first battles of the war would be fought, there were precious few soldiers left to guard against a Federal attack back home. To add to the state’s anxiety, the Lincoln government in April 1861 declared a blockade of the entire southern coastline from Virginia to the Rio Grande. Proclaiming a blockade was one thing—having enough warships to enforce it was another thing altogether. With most of the Federal attention focused on the major harbors of Charleston, Mobile, and New Orleans, and with few vessels available to guard the approaches to Galveston, the port became a haven for Southern blockade runners whose profits were high and risks were low. Even before the war, the city had established itself as the busiest anchorage on the Texas coast. Of the 300,000 bales of cotton produced in Texas in 1860, 200,000 were shipped from Galveston.

On August 14, 1861, Confederate Naval Commander William Wallace Hunter was ordered to proceed to Galveston and report to Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn, the military chief of the district. Hunter’s responsibilities included assuming the overall command of all Confederate naval forces in the area and, once in charge, “to take measures to guard against any surprise by the enemy in the harbor and bay of Galveston.” Hunter was also instructed to fortify Virginia Point across the bay from Galveston Island and to protect the two-and-a-half-mile railroad bridge that connected the island with the mainland. Hunter immediately directed all his energies and talents to fortifying Galveston, Brownsville, Pass Cavailo, and Sabine Pass. With only a few improvised “cottonclad” river steamers under his command, Hunter rendered efficient service to the army, transporting troops and munitions and guarding the coast from marauding expeditions.

Both Hunter and Brig. Gen. Paul O. Hébert, who assumed command of the district when Van Dorn was transferred east, considered Galveston essentially indefensible. Accordingly, they concentrated what few forces they had on Virginia Point and began fortifying the mouth of the Trinity River where it empties into the bay. All available guns, except for one 10-inch Columbiad that had to be left at Fort Point, were moved to the mainland, and all stores and ammunition were likewise salvaged. By the fall of 1862, when a Federal fleet suddenly appeared to threaten the city from the Gulf of Mexico, Galveston had become a ghost town.

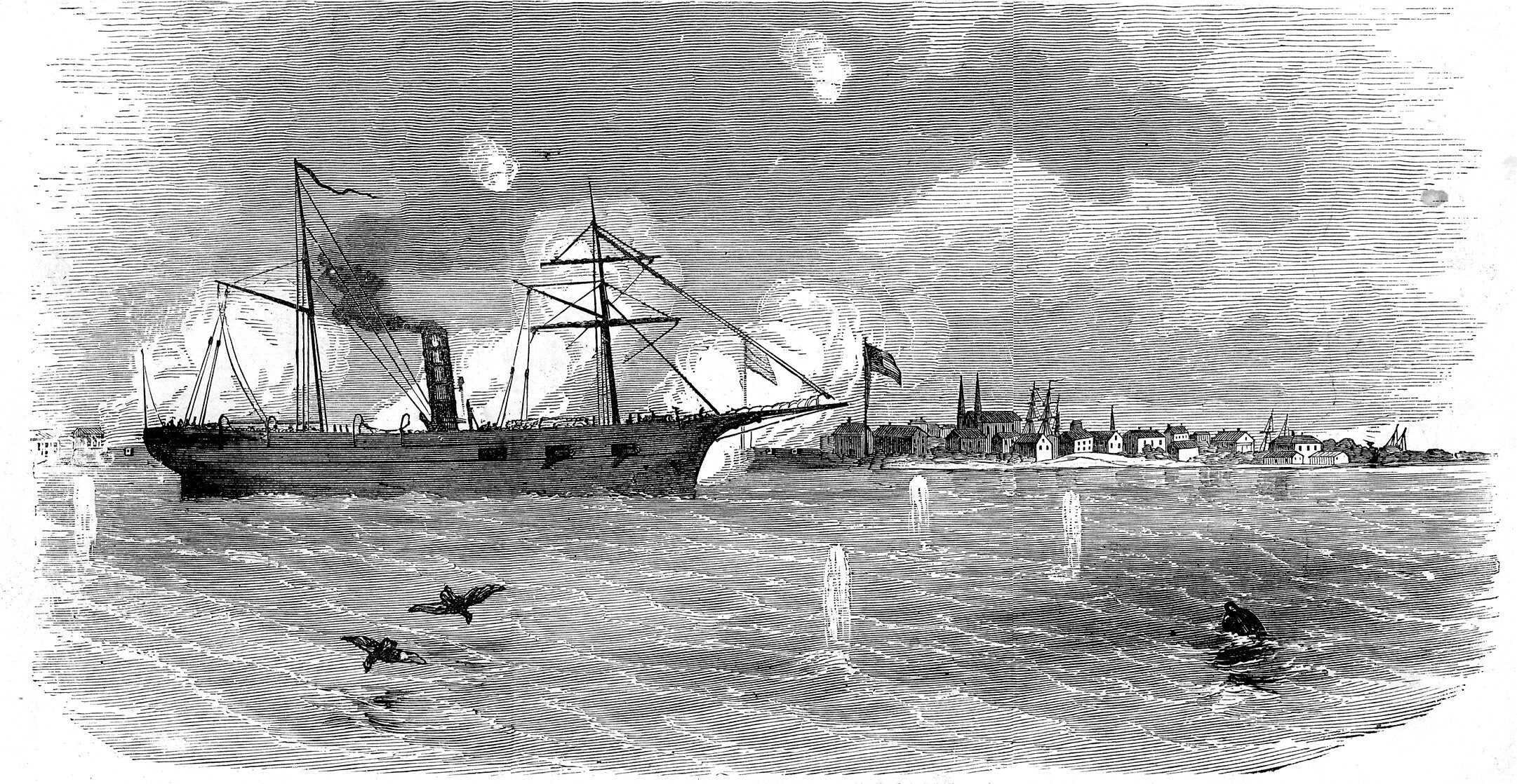

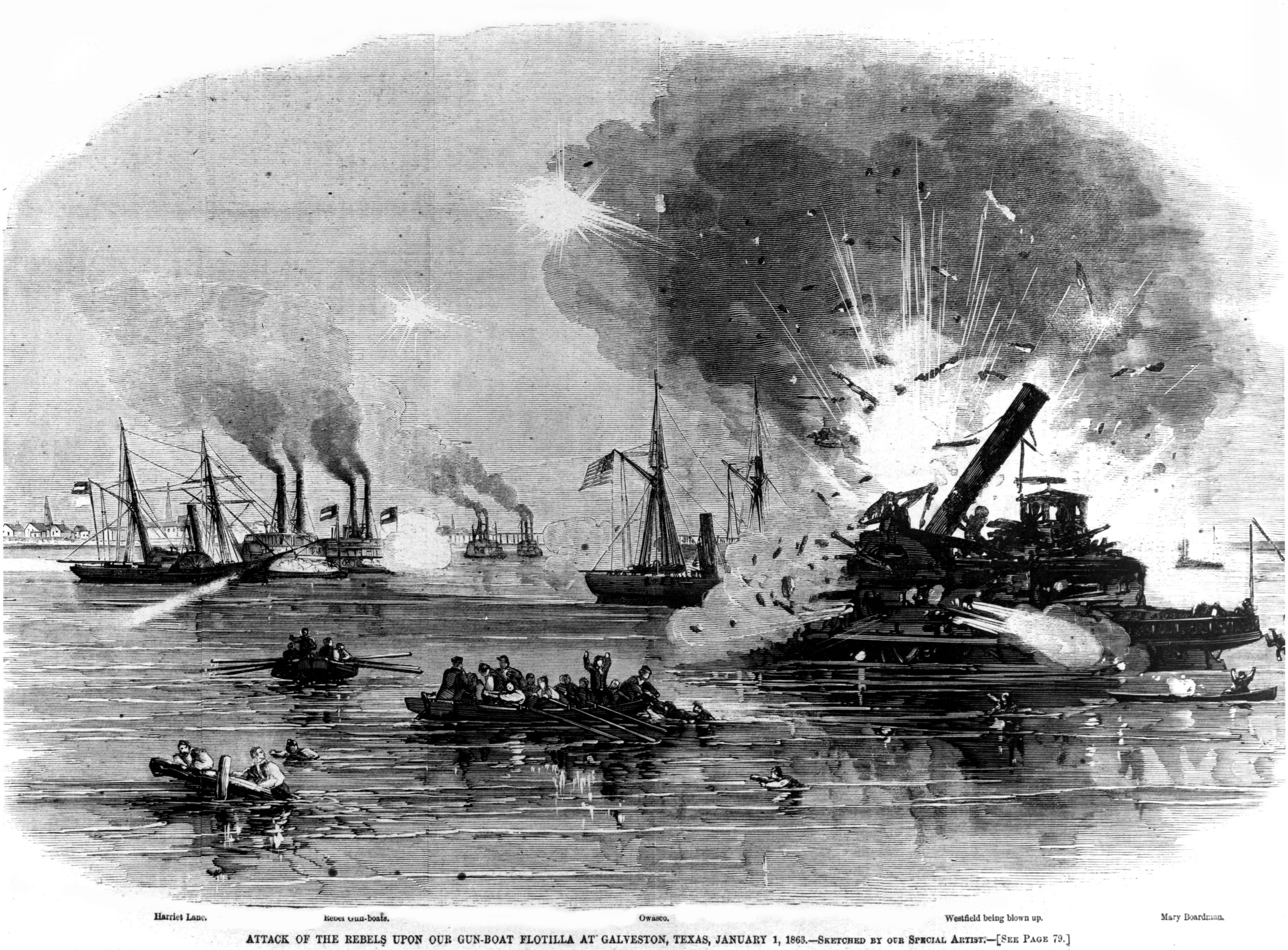

At daylight on October 4, 1862, eight Federal vessels heaved into view off the bar of Galveston Bay. The fleet included the Westfield, a sidewheel steamer with six guns; the Harriet Lane, another sidewheeler carrying five guns; the Owasco with five guns; the Clifton, carrying eight guns; and the mortar schooner Henry James. Three additional schooners loaded with supplies also accompanied the Union flotilla. The Federal armada was under the command of Commodore William B. Renshaw, who flew his pennant aboard the Westfield. At 7 am, Harriet Lane, flying a white flag, crossed the bar and steamed into the bay. Confederate soldiers watched apprehensively until she came opposite their position on Fort Point, at which time they opened fire with their lone 10-inch Columbiad, sending a shot whistling across the ship’s bow as a signal to stop. Her commander, Lieutenant Jonathan M. Wainwright, immediately complied and the Federal warship abruptly came to anchor.

Wainwright sent an officer ashore in a small boat to ask for an immediate interview with the Confederate commander. Confederate Colonel Joseph J. Cook, heading up the island defense, hurried to Fort Point and was told that Wainwright wanted him to come by boat to Renshaw’s flagship to meet with the fleet’s commander. Not having a boat at the point, Cook returned to Galveston to make the necessary arrangements. After much difficulty, the colonel finally located a small skiff and dispatched two officers on their mission. By this time, however, Wainwright had grown impatient. Turning Harriet Lane around, he steamed back over the bar to communicate with Renshaw himself. Soon, Southern soldiers at the point were aghast to see the entire Federal fleet, white flags flying from their peaks, cross the bar and head for the harbor. Cook’s messenger boat was making slow progress toward the oncoming Union warships, when suddenly the big Columbiad on Fort Point thundered again, sending another shell streaking across the bow of the lead Federal ship.

A Temporary and Uneasy Truce Between Forces

This time, however, the Union vessels refused to stop. Ignoring the white flags still flying from their own masts, they opened fire on Fort Point and the Confederate positions on the narrow neck of land between the fort and the city. The green Texas troops manning the Columbiad had never been under fire, and with shells from 20 heavy guns bursting around them, they quickly spiked their lone piece and fled toward the city. By this time, Renshaw’s fleet had come alongside the Confederate flag-of-truce boat carrying the two Southern officers. Renshaw ordered his flotilla to drop anchor and cease firing.

An uneasy silence now prevailed, as the two Confederate officers conferred with Renshaw on board Westfield. In his report, Cook described the results of the meeting: “At about 3:00 p.m. our flag-of-truce messenger returned to the city, bearing a demand from the enemy for the surrender of the city and demanding an immediate answer. I sent a messenger with the answer that I should not surrender the city, directing the messenger also to say to the commander of the fleet that there were many women and children, and to demand time to remove them. After some negotiation it was agreed that no attack should be made upon the city for four days; that during that time we should not construct any new or strengthen any old defenses within the city, and the fleet not to be brought any nearer the city. This arrangement gave us ample time for the removal of all who desired to leave the island, and also for the removal of our troops and material of every kind.”

Renshaw had no available troops with which to take possession of the city, but he effectively controlled every part of the town and island that lay within reach of his guns. At the end of the agreed four-day truce, the Federal commander was left with a stalemate. As a token gesture by Cook to avoid a useless bombardment, Renshaw was given permission to dispatch a detail to raise the American flag over the Customs House for a period of a few hours. With this done, the Union fleet closed the port and made access to the mainland over the railroad bridge a hazardous journey for the few Confederate troops still remaining in the city. Heavy planking was laid down on the bridge, and Confederate cavalry patrols frequently crossed over and visited the city, but for all intents and purposes, Galveston was now in Union hands.

On November 29, Confederate Maj. Gen. John B. Magruder, fresh from his stubborn defense of the Peninsula in Virginia, arrived to assume command of the Department of Texas. The tall, courtly Virginian, nicknamed “Prince John” by his admiring men, found the situation desperate. “On my arrival in Texas,” he wrote, “I found the harbors of this coast in the possession of the enemy from the Sabine River to Corpus Christi; the line of the Rio Grande virtually abandoned, most of the guns having been removed from that frontier to San Antonio, only about 300 or 400 men remaining at Brownsville. I resolved to regain the harbors if possible and to occupy the valley of the Rio Grande in force. I remained a day or two in Houston, and then proceeding to Virginia Point, on the mainland, opposite Galveston Island, I took with me a party of 80 men, supported by 300 more, and passing through the city of Galveston at night, I inspected the forts abandoned by our troops when the city was given up. I found the forts open in the rear, and taken in reverse by every one of the enemy’s ships in the harbor. They were therefore utterly useless for my purposes. The railway track had been permitted to remain from Virginia Point to Galveston, and by its means I purposed to transport to a position near the enemy’s fleet the heavy gun hereinafter mentioned, and by assembling all the movable artillery that could be collected together in the neighborhood, I hoped to acquire sufficient force to be able to expel the enemy’s vessels from the harbor.”

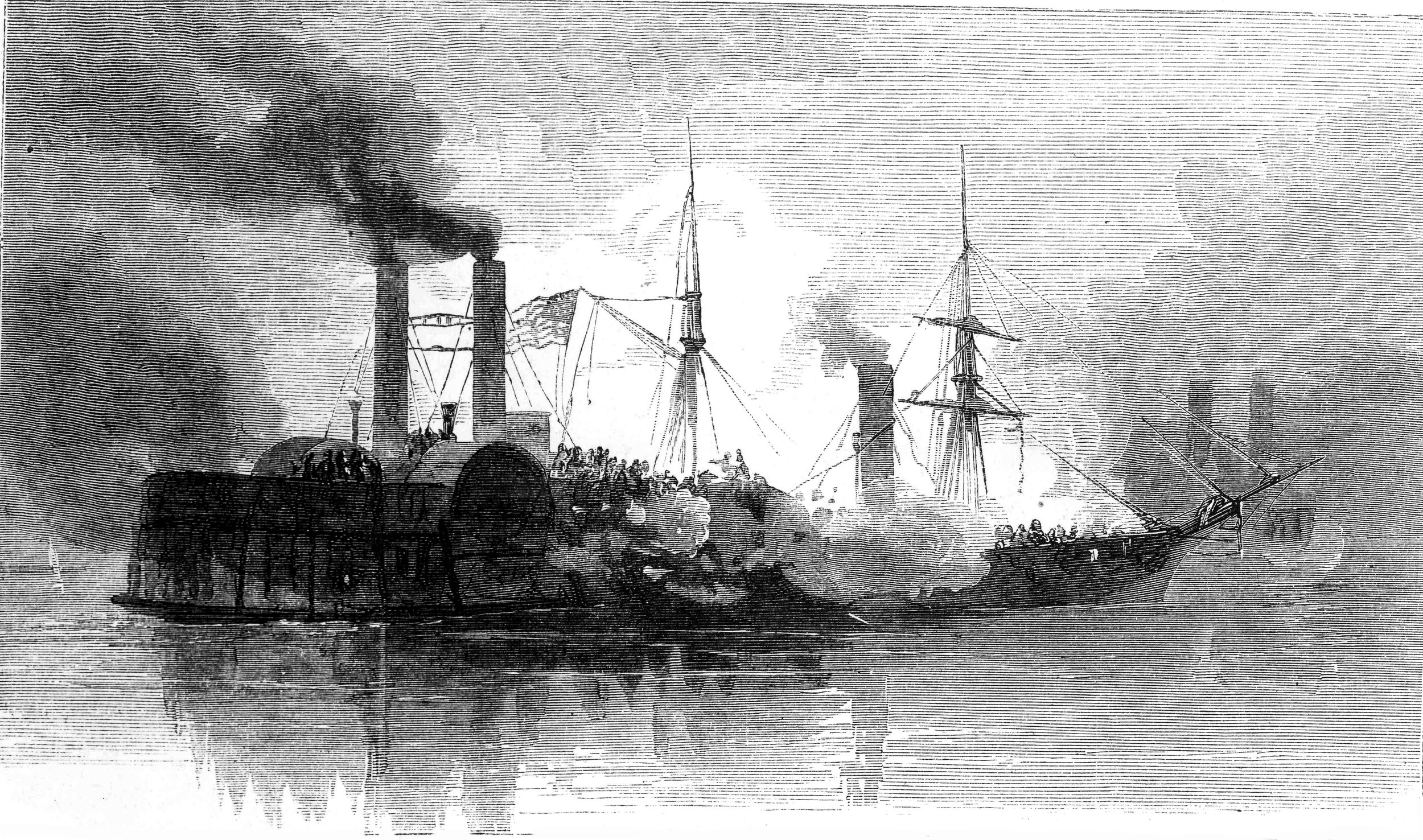

Acting on Magruder’s orders, Hunter was making every effort to arm several new boats that had been purchased by the Confederate government. Two iron-strapped river steamers, which were being operated by the Texas Marine Department, were reasonably large and could carry a sizable boarding party. These two boats, Bayou City and Neptune, were moved to Harrisburg, on the Buffalo Bayou, where workers began building bulwarks of lumber and cotton bales. Workers stripped off Bayou City’s upper cabins and pilot house, and cotton bales were placed on their sides and stacked three tiers high. Another row, two bales high, backed these and provided a fortified firing platform for sharpshooters. Boarding planks were constructed on each side of the boat and hoisted beside the smokestacks, where they could be dropped on an enemy vessel. Mounted on a pivot and protruding from among the cotton bales on the bow was an old 32-pounder that had been reworked into a rifle.

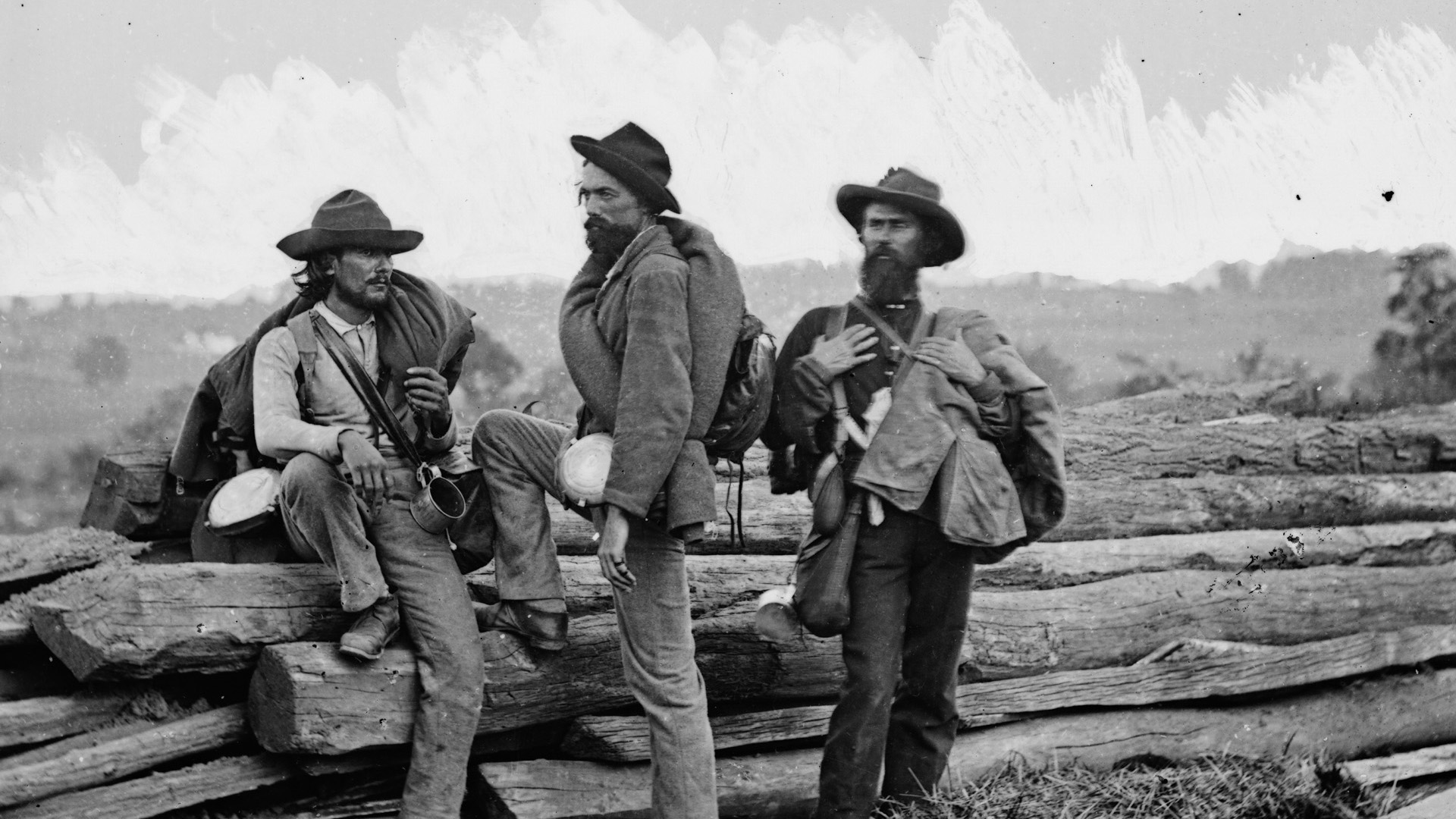

A company of cavalry from Colonel Tom Green’s 5th Texas and a number of volunteers from Colonel Arthur Bagby’s 7th Texas Cavalry went aboard as sharpshooters. These troopers had fought well as part of Brig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley’s famous brigade during the New Mexico campaign. From a distance the 165-foot Bayou City, under the command of Captain Henry S. Lubbock, resembled an ironclad ram. For her part, Neptune sported two small 24-pounder howitzers, and she too was armored with cotton bales. Commanded by Captain William H. Sangster, Neptune also carried a complement of sharpshooters from the 7th Texas Cavalry. Two transports, Lady Gwinn and John F. Carr, accompanied the tiny fleet. The latter vessels had cotton bales protecting their engines and machinery, but otherwise were unarmed. All the “Horse Marines,” as the cavalrymen described themselves, were armed with Enfield rifles and double-barreled shotguns.

The Confederate naval force of approximately 250 men was under the command of one-time riverboat captain Leon Smith, who, like Green, had fought in the Texas war for independence. Magruder had met Smith while in California, and being impressed with his knowledge of steamboating, had offered him a position on his staff. Along with the navy, Magruder was marshaling his land forces. Again drawing upon the Sibley Brigade, the Confederate commander tapped the untried 20th Texas Infantry, the 21st Texas Infantry Battalion, and detachments of the 2nd and 26th Texas Cavalry for the land attack. The units had been preparing to leave for Louisiana, but had been delayed by lack of transportation. Magruder scraped together all the artillery pieces he could find, and by December he had accumulated 14 field pieces, six larger siege guns, and one 9-inch Dahlgren that he had mounted on a railroad flatcar.

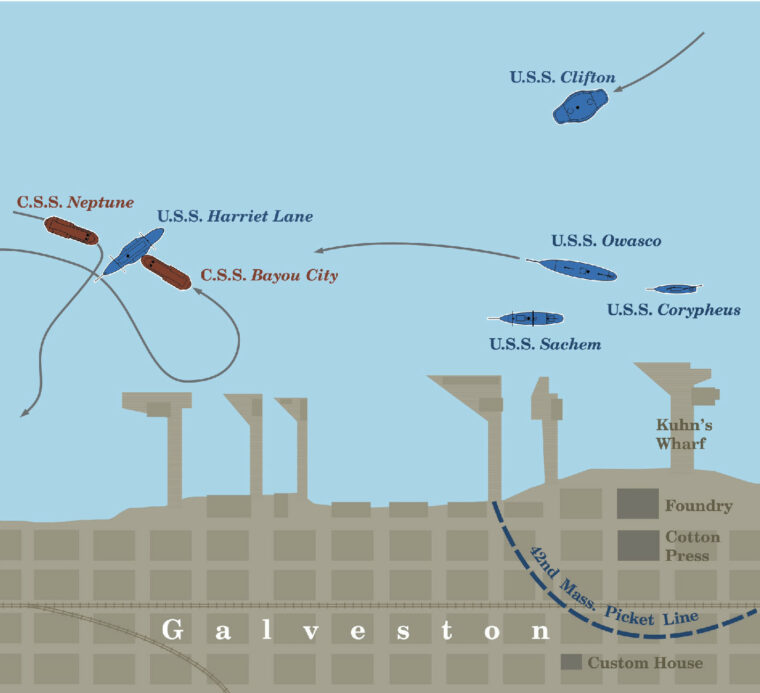

Magruder’s haste in preparing his forces was well founded. On Christmas morning, 240 members of Companies D, G, and I of the 42nd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, under the command of Colonel Isaac S. Burrell, landed on Kuhn’s Wharf at the end of 18th Street in Galveston. Working with haste, the New England troops ripped out the planking leading from the wharf to the main dock area, which was called the Strand, and proceeded to erect barricades and firing positions on the wharf itself. With the heavy naval guns at their backs, Burrell was confident that his men could successfully resist any determined Southern attack. Having learned through informants that more Union troops were on their way to Galveston as reinforcements, Magruder realized that he had to act quickly.

Wednesday evening, December 31, was clear and cold. A brilliant full moon cast its rays over the placid waters of Galveston Bay, where the Federal warships swung gently at their anchors. On board each vessel, deck watches began their usual rounds. Hammocks were lowered by tired Union sailors, who hoped the persistent rumors of a Rebel attack would prove untrue for at least one more night. On Virginia Point, however, Confederate Army forces were already on the move. Horses and mules strained at their harnesses as they pulled the six heavy siege guns across the wooden planking laid down on the long railroad bridge. Gray-clad troops trudged along beside, while other willing hands pushed ahead the old railroad flatcar carrying the 9-inch Dahlgren.

Captain S.T. Fontaine and the men of the 1st Texas Heavy Artillery had the farthest to go. Their objective was to occupy Fort Point at the mouth of the harbor and direct the fire of their heavy guns on the Federal fleet in the bay. Meanwhile, Captain George R. Wilson’s six siege guns would engage the Massachusetts troops on Kuhn’s Wharf, while the big Dahlgren was run up to a point only 300 yards from the Harriet Lane, which was anchored off the end of 29th Street. The remaining artillery pieces were positioned within the town, where they could bring their fire to bear on the other Federal vessels in the bay. In all, five formidable warships lay offshore, their 30 heavy guns covering the Union troops on the wharf. Meanwhile, Cook had assembled a determined attack force of 500 men whose mission was to storm the Northern troops barricaded on the wharf. Magruder planned to have everyone in place by midnight, at which time he would give the signal to open fire.

By the appointed hour, Smith and his cottonclad flotilla had reached a point just north of Pelican Island. Fearful that he would be spotted in the bright moonlight—he was, and lookouts aboard the Harriet Lane flashed the alarm—Smith ordered his forces to withdraw northward several miles up the bay. With the faint sound of hissing steam audible from the engine rooms, the weary Confederate Horse Marines dropped down behind their cotton bales for a short period of rest, while Smith and his anxious commanders waited for the opening sounds of the land attack.

The Battle of Galveston Begins with the Boom of a Siege Cannon

Midnight came and went, and all was still quiet in Galveston. Confederate soldiers, careful to stay out of the bright moonlight, huddled in the shadows of the buildings and in alleyways along the waterfront. Weapons were checked and double-checked. Some men, aided by the moonlight, wrote letters to their families and sweethearts. Waiting was always the most difficult task for soldiers, and it was now well past the appointed time and the order to attack still had not come. Unknown to those awaiting the signal, Magruder had decided to delay the assault in order to be certain that Fontaine had reached his position at Fort Point. By 4 am, the moon had slipped below the horizon and a thin mist spread its veil over the darkened bay. While their horses were hurried behind some of the brick buildings, Texas gunners jostled their pieces to more advantageous firing positions and squinted across their sights at the enemy vessels still visible by the faint light of the stars.

A little after 4 am, Magruder walked to the center siege cannon located at the end of 20th Street and pulled the lanyard. The heavy gun responded with a thunderous roar, and at once the entire Confederate line exploded in a sheet of flame as every gun opened up. The Battle of Galveston had begun.

It did not take the Federals long to reply. Within minutes every gun that had the range was sending charges of grape and canister whistling through the midst of the Confederates on the Strand. The deadly iron balls tore into buildings and flesh alike. Cries of the wounded mixed with the dust and smoke as Texas gunners struggled to return fire. The Union gunners began to alternate between shells and canister and the streets and alleys leading to the Strand became a fiery death trap of massive explosions and streaking canister.

Four miles to the north, the thunderous discharges were distinctly heard. Smith, shouting into Bayou City’s speaking tube, yelled to the engine room, “Give me all the steam you can crack on!” Neptune came alongside and the two cottonclads’ paddlewheels churned the water to foam as they began to pick up speed. Black smoke poured from their stacks as engines puffed and throbbed, while high-pressure steam hissed from escape valves. The sleepy Horse Marines were now wide awake, and with dry mouths and pounding hearts they scrambled for their positions behind the cotton bales.

On the Strand things were not going well for Magruder’s Texans. Federal warships had edged in closer to the wharves and now, at less than 300 yards, were sending their charges tearing into the enemy positions. Some Confederate gun crews had abandoned their pieces, while others struggled bravely to maintain their fire. Even the heavy Dahlgren on the flatcar was abandoned. Some damage had been inflicted on the enemy vessels, but not enough to drive them off. Seeing the danger, Cook led his 500-man storming party in a desperate bid to dislodge the Massachusetts troops barricaded on Kuhn’s Wharf. The green troops of the 20th Texas immediately ran into trouble. Wading through the cold water from the Strand to the wharf, they attempted to raise their scaling ladders, only to find that they had miscalculated the depth of the water and that the ladders were too short. Fire from the Union ships combined with the musket fire from the 42nd Massachusetts spread panic among the floundering Texans, and they scrambled for any cover they could find.

Knowing that it would be suicide to try to keep his troops and gunners in position at daylight, Magruder ordered his men to begin falling back. Exhausted and dazed Confederates troops, many encrusted with blood, dust, and gunpowder, stumbled through the town, some not stopping until they reached the Gulf shore. The decision to shield the horses behind the buildings proved fortuitous, for most gun crews were able to retrieve their pieces. Fontaine’s exposed guns, however, were spiked and abandoned at Fort Point. As daylight began to reveal the carnage and destruction around them, a feeble cheer arose among the Confederate troops. Off to the north, through the smoke and early morning haze, the Horse Marines were coming.

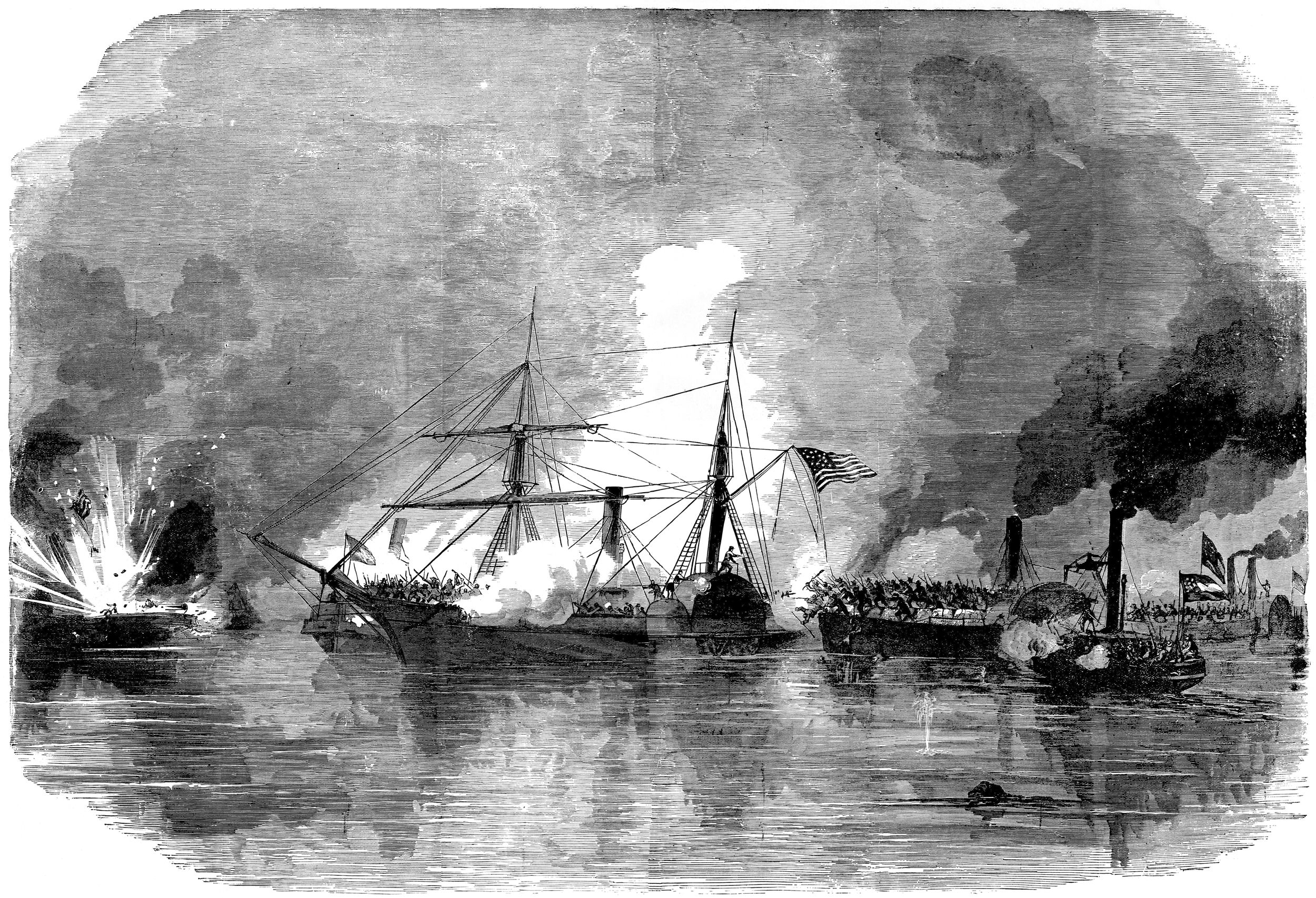

Puffing and snorting from high-pressure steam, the Confederate cottonclads drove straight for the Union vessels. Rosin and turpentine had been thrown into the improvised vessels’ furnaces to increase their speed. When Bayou City and Neptune drew within range, their bows suddenly belched smoke and flame as their 32-pounder and howitzers let fly at the Federals. While the Union gunners on board Harriet Lane hurried to pivot their pieces to meet the unexpected new threat, Texas cavalrymen aboard Bayou City loaded another round and sent it streaking toward the Harriet Lane. Their aim was true. The shell tore through the side of the Union gunboat, blasting a hole that was big enough for a man to crawl through. Someone shouted for them to give the Yankees another New Year’s present, and the old 32-pounder exploded in a mass of flames, sparks, and spinning pieces of jagged iron. When the smoke cleared, the ship’s captain and several others lay lifeless on the deck, their bodies torn to pieces by the misfired gun.

On came the cottonclads, Bayou City slightly in the lead. The Horse Marines opened a blistering fire on the Federal warship with their Enfield rifles. Blue-clad sailors scurried for cover, abandoning any attempt to return the fire. Captain Lubbock shouted for the pilot, Captain Michael McCormick, to ram the Union vessel. McCormick later reported, “The Harriet Lane was lying at anchor with steam on, swinging with a strong ebb tide, bow to the west. I was instructed to endeavor to so hit her as to allow the men a chance to board. Going with a strong ebb tide I dared not run against her bow, so I endeavored to strike forward of the larboard wheelhouse. Owing to the position of the Lane and the strength of the ebb tide, I missed my aim, struck a glancing blow and passed by. The wheelhouse and upper works of the Harriet Lane, being very strong, tore off the outside planking of the Bayou City’s larboard wheelhouse and side.”

Blasts from double-barreled shotguns now mixed with the Enfields, while crewmen swung axes to cut the lines holding the port boarding ramp. The interval proved too great, however, and the ramp splashed into the water, where it swung to the rear and was smashed to pieces by Bayou City’s revolving wheel. The ship made a slow turn to port, as frantic crewmen tore at the wreckage in an effort to free the port wheel. Meanwhile, Neptune bore down on the beleaguered Harriet Lane. Captain Sangster ordered his helmsman to bring the bow a little more to port for a better ramming angle. Enemy cannonfire struck Neptune’s deck, sending cotton bales flying and deadly wooden splinters whizzing through the air. With a full head of steam, the charging Neptune slammed hard into Harriet Lane, 10 feet behind her starboard paddlewheel.

The men of the 7th Texas Cavalry, having been thrown to the deck, struggled without success to grapple and secure the enemy vessel. Other Union warships, notably the Owasco, approached to aid their stricken comrade, and a devastating fire was poured into the Confederate cottonclad. Sangster recognized at once that his ship was in trouble and ordered the engine room to reverse engines and back away. Water poured in through the shattered bow and several holes punched in her side by Owasco’s fire. The Neptune was sinking, and Sangster steered for the shallow water off 32nd Street. There, as she settled into the mud, the Horse Marines, standing knee-deep in water, continued to pour musket fire into the Harriet Lane.

The Scene on the Federal Vessel was one of Absolute Carnage.

By this time, the crew aboard Bayou City had cleared the debris from her port wheel and Lubbock hastened toward Harriet Lane, which was attempting to back down the channel. With the musket fire from the Horse Marines keeping the Federal bluejackets from manning their guns, Bayou City was able to maintain her collision course without drawing enemy fire. With a tremendous crash, the Confederate boat drove her pointed bow deep into the portside paddlewheel of the Union ship. The crash sent stunned men on both ships tumbling across the decks as iron and wood splinters hurtled through the air. Harriet Lane heeled far over to starboard. Timbers buckled and broke as the iron wheel braces impaled the Bayou City, locking the two vessels together in a death embrace.

Smith scrambled to the shattered bow and began slashing at the netting with his cutlass. Cutting the ropes free, he called for his men to follow him and bounded onto the deck of Harriet Lane. With a Rebel yell, the Texas troops downed the rest of the netting and scrambled aboard with pistols drawn. The scene on the Federal vessel was one of absolute carnage. Dead Union crew members lay sprawled across the deck, along with their commander, Wainwright. Harriet Lane’s executive officer, Lt. Cmdr. Edward Lea, lay dying with five bullets in his abdomen. As the excited Texans surveyed the scene of destruction, a Federal sailor stepped out from behind a hatch, raised his hands, and surrendered the ship.

Once the commander of Owasco, the closest Union warship to Harriet Lane, realized what had happened, he ordered his ship underway in an effort to recapture her. Soon Owasco’s guns were delivering a hot fire at her beleaguered sister ship. From a distance of 1,000 yards, Owasco’s powerful 11-inch Dahlgren hurled round after round of shell and canister at the Confederate boats. Gray-clad troops scurried for cover. Several men attempted to train Harriet Lane’s guns on the other Federal warship, but she was listing so badly from the collision that the guns could not be brought to bear. Confederate Enfields continued to bark, their fire swelling in intensity as more and more Texans fought savagely to retain their prize. Union sailors aboard Owasco were soon driven from their guns by the intense fusillade, and their commander ordered his vessel to back away.

An uneasy quiet now settled over the bay. A white flag fluttered from Harriet Lane’s stern, while the Horse Marines, fearful that the Federals would renew the attack, worked to separate the two vessels. It was no use—Bayou City’s bow was jammed tightly into the wheel braces of the Union ship. The tender John F. Carr was called and, passing a line, attempted without success to pull the two boats apart. The two antagonists were dragged slowly toward the 27th Street wharf, where Texas troops gathered on the bow and tried rocking them apart. Bayou City’s stem, however, still would not budge. It would take the skill of several mechanics and carpenters to eventually separate the two vessels.

While the Confederates struggled to untangle the two warships, Lubbock and Smith initiated a daring bluff to guarantee complete victory for Magruder’s forces. Ordering a small boat lowered, Lubbock and Harriet Lane’s acting master, J.A. Hannum, ordered the oarsmen to row him to the closest Union vessel, Clifton. Clambering aboard the Union warship, Lubbock boldly demanded the surrender of the entire Federal fleet and instructed the Federal commander to choose one ship that would be allowed to carry the surviving Union crews out of the harbor. Captain P.L. Law, Clifton’s commander, explained that he did not have authority to surrender the entire Union flotilla, but would have to communicate with Renshaw. Lubbock agreed to the request and stipulated a period of three hours in which Law was to transmit the demand to Renshaw and return with the commander’s answer.

While the demand for surrender of all the Northern vessels was being carried to the Westfield, Magruder ordered the 130 prisoners from the Harriet Lane removed and marched through town to safety in the event that shelling should begin anew. Also removed were the dead and wounded, including Harriet Lane’s ill-fated commander, Wainwright, and his executive officer, Lea. As the bodies were carried ashore, Texas cavalrymen watched in silence as the stretcher bearing the lifeless form of Lea passed by. Walking beside the litter was the young Union officer’s father, Major A.M. Lea of the Confederate Army, a member of Magruder’s staff. The following day, Wainwright and Lea were buried with full military honors. Confederate and Federal officers stood quietly together, while a grieving Major Lea read the solemn service of the Episcopal Church for the burial of the dead.

Back on Kuhn’s Wharf, Burrell’s three companies of the 42nd Massachusetts were still holed up behind their barricades. Peering over the obstructions, Burrell observed a flag-of-truce team approaching, headed by Brig. Gen. William R. Scurry, commander of the 2nd Texas Cavalry. Scurry demanded the immediate surrender of the 240 Union troops on the wharf. Seeing the white flags flying from all the Federal vessels in the bay, Burrell felt that he had little choice but to surrender his entire command.

Confederate Losses Amounted to 27 Killed and More Than 100 Wounded.

It was now after 7 am. The end of the three-hour truce period was approaching and still no word had come from Renshaw. The Federal commander, whose flagship, Westfield, had run aground near Pelican Island at the beginning of the engagement, apparently was panic-stricken. He refused to surrender his vessels, but rather than order continued resistance to the Southern forces, Rendshaw instructed Law to order the commanders of the remaining Union warships to attempt to escape as best they could. Against the remonstration of his own officers, Renshaw ordered his crew to board the nearby transports Mary Boardman and Saxon, and laid a fuse to the magazine, intending to blow up his flagship. Once the crew and their belongings were safely aboard the transports, Renshaw poured turpentine over the deck and lit the fuse. As he descended the ladder into his gig, Westfield exploded in a thunderous blast, killing Renshaw, three other officers, and the entire crew in the waiting boat.

While the Federal commander was suicidally destroying his flagship, Law had proceeded down the channel toward the wharves, informing the commanders of the four remaining warships, the schooners Velocity and Corypheus and the screw steamers Sachem and Owasco, that they must escape or destroy their vessels. Lubbock, still awaiting Renshaw’s response to his surrender demand, hurriedly rowed out to confer with Law and ascertain why the Westfield had exploded. Even while the two men spoke, the Clifton was getting underway. Angrily, Lubbock accused Law of a breach of faith and returned to his boat. Along the wharves, Confederate officers watched in growing astonishment as all the Federal vessels, white flags still flying from their mastheads, began running for the bar.

Southern artillery crews unlimbered their guns and, with some hesitation because of the white flags, opened fire on the fleeing vessels in an attempt to prevent their escape. Smith dashed aboard the John F. Carr at the 27th Street wharf and, calling for volunteer sharpshooters, ordered the tender in pursuit. Even at full throttle, however, the little steamer was unable to catch the Union warships before they had crossed the bar. With the rough waves of the Gulf breaking over the John F. Carr’s fragile bow, Smith abandoned the chase and returned to the city. He was consoled somewhat by capturing and towing back with him the Federal coal bark Elias. It had been six hours since Magruder had jerked the lanyard of the center artillery piece to signal the beginning of the Confederate attack.

The retaking of Galveston was not without a price. Confederate losses amounted to 27 killed and more than 100 wounded. The Neptune sank into the mud off 32nd Street as a result of her collision with the Harriet Lane, and the Bayou City was badly damaged. Federal forces counted five fatalities and 12 wounded on board the Harriet Lane. The remaining crewmembers were taken prisoner. Owasco sustained 16 casualties, and 12 crewmen had died in the premature explosion of the Westfield.

Harriet Lane would be repaired and later enter Confederate service as the CSS Harriet Lane, while the guns from Westfield were salvaged and employed in the defenses of the city. Galveston, although blockaded, would remain in Southern hands until the very end, becoming the major port of supply for the beleaguered Confederate forces west of the Mississippi. In addition to becoming a safe haven for blockade runners, the recapture of Galveston denied the port to the Federals as a forward base of operations and, more importantly, protected the interior of the state from northern invasion. Through the courage and determination of the Confederate naval forces and their Horse Marines, the largest port west of New Orleans had been returned to the Southern cause.

There was one error in the opening of this story. The men in gray in Texas at the beginning of the war did not rush to Virginia. In fact only three Texas Units with Hampton’s Legion and a Georgia unit with the three made Hood’s Texas Brigade. Walker’s Texas Division stayed for the most part of the war in the Trans-Mississippi Dept. A number of dis-mounted Texas Cavalry units and 2 more Infantry units would become Grandbury’s Brigade in 1864. Second Texas surrendered and exchanged would never be reformed. But with limited manpower Texa didn’t have a large number of units.

The US Revenue Cutter Harriet Lane 1857 was not Navy. The Treasury Department transferred the Revenue Cutter Service to serve as a separate service under the Navy during times of war or by Presidential direction.

All Revenue or Coast Guard Cutters stayed Cutters and never became Naval Ships and were never Maned by Naval Sailors nor commanded by Naval Officers.

There have Army and Navy Ships, Craft, and Boats maned and commanded by Coast Guardsmen.