By Jim Heenehan

Late in the morning of January 2, 1863, Confederate Maj. Gen. John Breckinridge gazed through the brush at newly arrived Union infantry occupying a partially wooded hill to his front near Murfreesboro, Tenn. The Yankees had moved in the day before, alarming the local Rebel commanders. Some suspected a trap, prompting the general to crawl beyond his picket line for a look.

Just then a rider galloped up, summoning the Kentuckian to General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee headquarters. The day was cold and overcast as Breckinridge mounted his horse to ride back to join his moody commanding officer. He could not have been enthused about the meeting. Bragg’s unfair criticism of him after the 1862 Kentucky campaign, coupled with Bragg’s seemingly vindictive execution of a young soldier in Breckinridge’s command the month before, had left the two men bitter enemies. Things were about to get worse.

Two days earlier, December 31, the Confederates had opened the battle of Stones River (also called Murfreesboro) by surprising Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland in a dawn attack that staggered the Yankees. The Union line bent but never quite broke. Bragg’s assumption that the battered Yankees would retreat that night was dashed when New Year’s Day revealed the enemy still in place. Now Bragg had to come up with a new plan. Thirty hours later he had it—Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk’s Corps would hit the Federal left. But first Bragg had to take care of a preliminary matter, which is where Breckinridge came in.

Just after noon Breckinridge rode up to army headquarters, dismounted, and joined his commanding officer by a giant sycamore tree near the Nashville Pike. The personal animosity between the two men was perhaps aggravated by their appearances and personalities. Breckinridge, with his long mustache and striking profile, was possibly the handsomest general in the Southern army. Bragg, with his bushy beard and wrinkled face, was undoubtedly the ugliest. While the dashing Breckinridge was the epitome of a Southern gentleman, Bragg’s blunt, critical style made him a hard man to like and an easy man to hate.

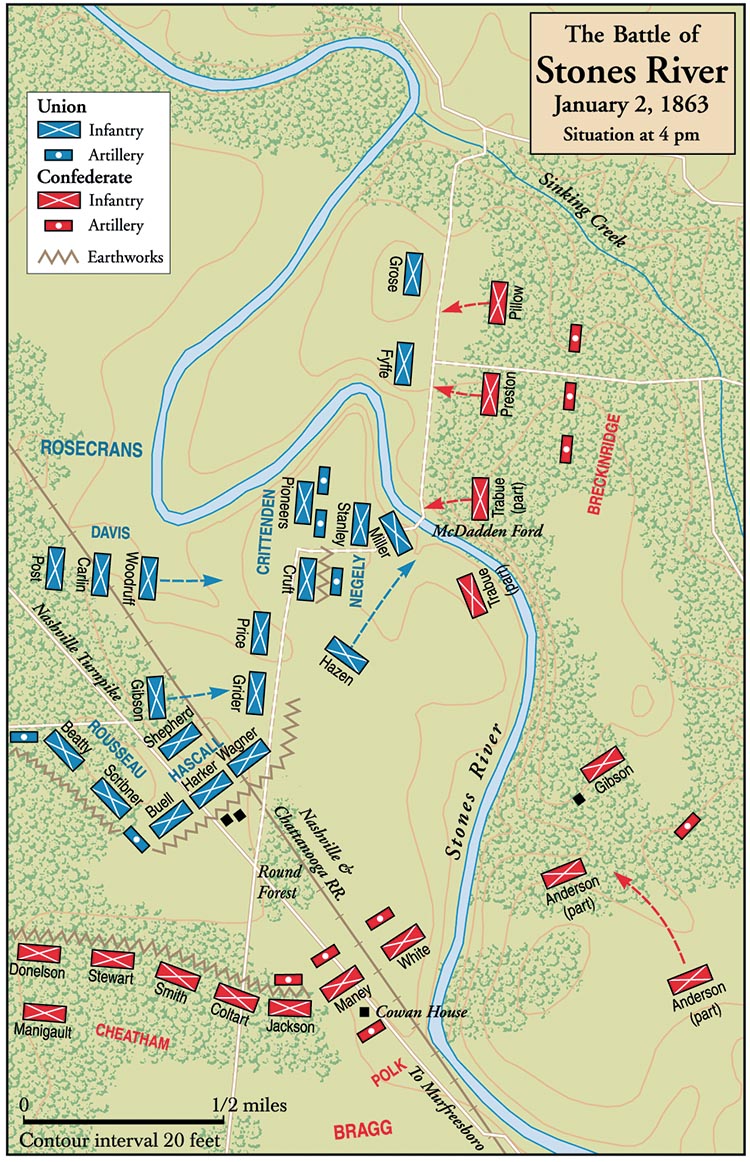

Now joined by his subordinate, Bragg explained his proposed assault. The previous day a Yankee detachment had crossed Stones River at a spot called McFadden’s Ford, occupying a large hill on the river’s east bank, fronting Breckinridge’s command. The hill provided Rosecrans with a natural artillery platform that could decimate the right flank of Bragg’s proposed attack. Before Bragg could launch Polk’s assault, he insisted that Breckinridge take that hill.

Breckinridge was stunned. He had just returned from a reconnaissance of that very hill and was convinced an attack would be suicidal. Strong detachments of Yankees were situated on and near the grassy prominence. The Confederates would have to attack over several hundred yards of open fields subject to Union artillery fire. Union reserves might be massed to the rear of the hill. Even if he took the hill, it was flanked by a taller hill across the river to the northwest. Yankee artillery placed on this far hill could make things hot for his men, even if they managed to capture the near hill. Warming to his argument, Breckinridge began to trace the position in the dirt when Bragg stopped him. “Sir, my information is different. I have given the order to attack the enemy in your front and expect it to be obeyed.”

Bragg’s Bold and Risky Attack Plan

That ended the discussion. The assault would go forward as planned. Bragg ordered Breckinridge to attack with his own four brigades at 4 pm—just 90 minutes away. Bragg assured the Kentuckian that he had arranged for two dismounted cavalry brigades to advance on his right. He also advised Breckinridge that his division’s three artillery batteries would be supplemented by two batteries (10 guns) under the command of Captain Felix Robertson. All five batteries were to advance with the infantry. Once the infantry had taken the hill, the batteries would unlimber. The men were to entrench, securing the position. The infantry was not to advance beyond the hill.

By starting the attack 45 minutes before sunset, Bragg calculated that the Federals would not have time to organize a counterattack to retake the hill before nightfall. The next morning, strengthened by breastworks, the Confederate artillery could enfilade the Union lines across the river as Polk’s infantry smashed them from the front.

Bragg’s subordinates did not share his confidence. Breckinridge thought the plan was insane. Coming across one of his brigade commanders, Brig. Gen. William Preston, he exploded: “General Preston, this attack is made against my judgment, and by the special order of General Bragg. Of course we must all try and do our duty and fight as best we can. If it should result in disaster, and I be among the slain, I want you to do justice to my memory and tell the people that I believed this attack to be very unwise, and tried to prevent it.”

Brig. Gen. Roger Hanson, commander of the Kentucky “Orphan Brigade,” favored more direct action. Upon hearing of the proposed attack, Hanson cried that he would kill Bragg to stop him from murdering his own men.

Breckinridge was having a bad day and it got worse. He argued with Captain Robertson, commander of the 10-gun detachment, over whether Robertson’s cannon were to move forward with the infantry or wait until the Rebels had first captured the hill. Breckinridge was sure that Bragg wanted the cannon to accompany the infantry, but Robertson refused to move his two batteries until the infantry had taken the hill. In disgust, Breckinridge agreed to let Robertson advance his guns as he thought best.

As 4 pm approached, Breckinridge realized that the promised dismounted cavalry support for his right had not arrived. His men would be taking flank fire from the Union left as a result. Even nature mocked him as a hard, driving sleet kicked up, further complicating his attack.

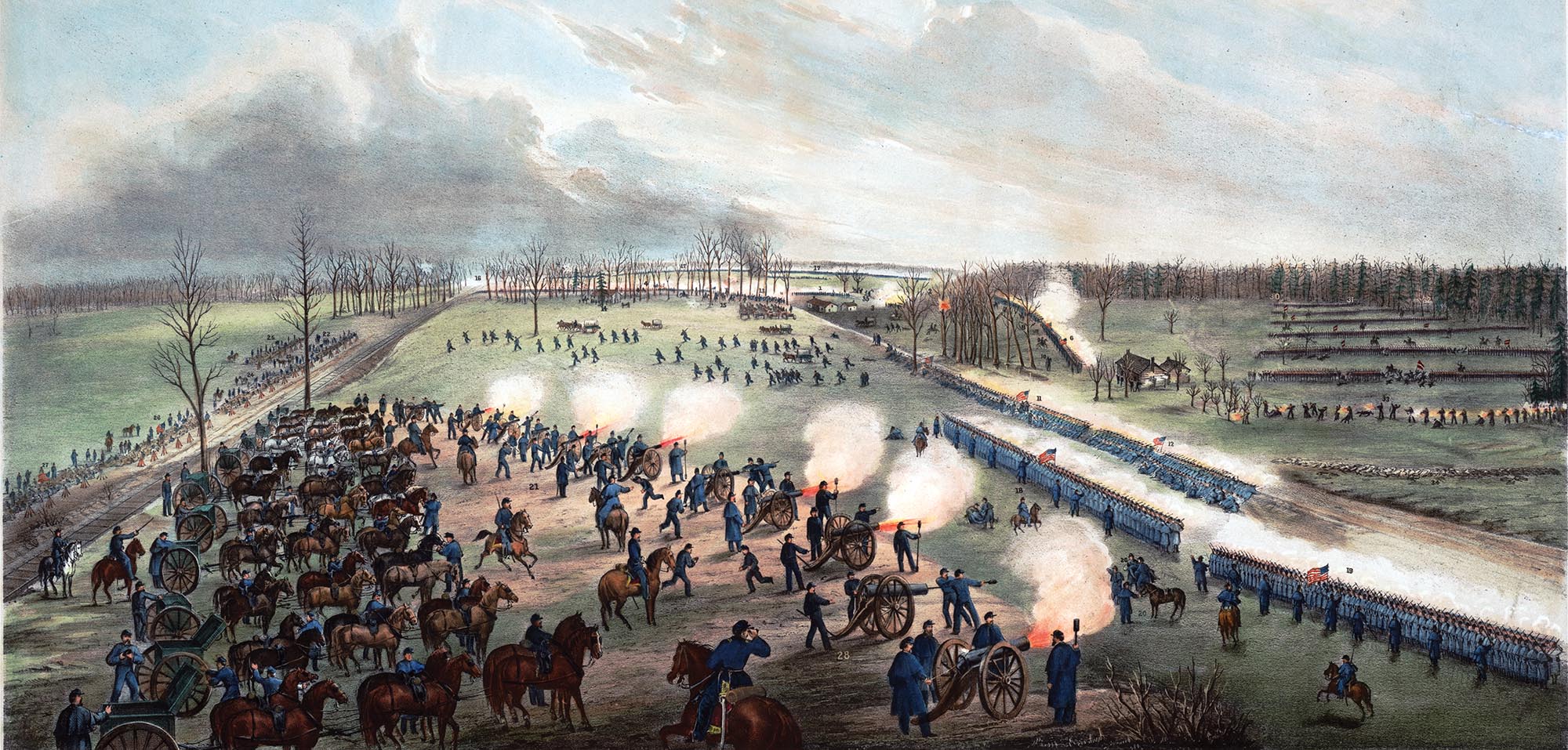

Suddenly a single cannon fired—the signal to attack! Putting his apprehensions aside, Breckinridge ordered his brigade commanders to commence the assault. Hanson galloped up to one of his regimental officers, shouting, “Colonel, the order is to load, fix bayonets, and march through this brushwood. Then charge at the double-quick to within a hundred yards, deliver fire, and go at him with the bayonet.” Soon 5,000 men advanced, bayonets bristling and colors flying.

Breckinridge organized his troops in a dense formation consisting of two double brigade lines separated by no more than 150 yards (the normal distance was 300). Opposing them 1,000 yards away on the east side of Stones River were four Union brigades (4,000 men) and a six-gun battery, all commanded by Colonel Samuel Beatty. The first two Yankee brigades under Colonels Samuel Price and James Fyffe were employed in a double line, a six-regiment front line backed by a four-regiment second line. The two right rear regiments occupied the hill that was the focal point of Bragg’s attack.

A third Union brigade under the command of Colonel Benjamin Grider was in reserve behind the hill while a fourth, led by Colonel William Grose, had been detached from Brig. Gen. John Palmer’s Division to support Beatty’s left rear. The six-gun, 3rd Wisconsin Artillery was also posted near Grose’s reserve position.

Unbeknownst to Bragg and Breckinridge, the Union dispositions were faulty. The front line brigades of Price and Fyffe were too far apart for mutual support, while Grose’s Brigade was too far to the rear. Grider’s men assumed that no Confederate attack would be launched so late in the day and had stacked arms. Furthermore, the front line of the Federals was isolated because only the rear elements were in close proximity to the main Union force across the river. One more thing hidden from the Rebels was the extent of Yankee artillery support. But they would find out soon enough.

General Hanson Redirected His Murderous Intent from Bragg to the Yankees

The Rebel lines moved out as if on parade and immediately began taking artillery fire. One Union shell exploded, killing and maiming 18 Confederates. But the Rebels closed ranks and kept coming. Instinctively, the men bent low to avoid nature’s frozen pellets and the more lethal fusillades of their blue-clad opponents.

General Hanson, redirecting his murderous intent from Bragg to the Yankees, led his Kentucky boys toward the Federal troops guarding the hill. Hanson was fortunate that the brushwood bordering Stones River helped screen his left flank. Although the river bent toward Hanson’s men, causing them to bunch as they squeezed right, the brushwood provided a measure of cover unavailable to the Tennessee, Florida, and North Carolina troops marching through a cornfield to Hanson’s right.

The Federals facing Hanson were lying low in a ridge line at the base of the hill, invisible to the general and his men. Ironically, Hanson’s Kentucky troops were attacking Colonel Price’s Brigade, which included two Kentucky regiments of its own. Price’s men let the Confederates come to within 100 yards before leaping to their feet and firing a severe volley. Momentarily staggered, the Orphan Brigade closed ranks, advanced a few paces, and delivered a sharp return volley. The bullets hit their mark and dozens of Federals keeled over. Other Yankees flinched instinctively before attempting to reload. Suddenly a thunderous Rebel yell rent the air as Hanson’s Kentuckians lowered bayonets, charging the enemy. A handful of Yankees fired a parting shot before the entire Union force broke for the rear. An admiring Breckinridge shouted approvingly, “Look at old Hanson!”

Their blood rising, the Orphan Brigade eagerly pursued their routed foes. Farther up the hill the Union second line vainly tried to draw a bead on the advancing Rebels, whose charge was screened by the retreating Yankee first line. Confusion gave way to panic when some enterprising Confederates crossed the river and began hitting the second Federal line with flank fire. The Union line would not hold long.

But things were not going as smoothly on the Confederate right. In the absence of the promised dismounted cavalry support, the Rebel line was too short. Union Colonel James Fyffe saw his opportunity and began shifting his mixed Indiana/Ohio Brigade to rake the Confederate right flank. The front Rebel brigade had difficulty adjusting to this threat as Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow, appointed to its command by Bragg moments before the attack, was skulking behind a tree.

Lt. Col. F.M. Lavender of the 20th Tennessee on the far end of Pillow’s second line saw the problem, and wheeled his unit around to cover the first line’s exposed flank. He was shortly joined by Captain E.E. Wright’s Tennessee battery (unlike Captain Robertson, Breckinridge had advanced his division artillery with the infantry). Wright’s added firepower decidedly tipped the balance in the Rebel’s favor and the Federals pulled back.

Colonel Fyffe now faced a dilemma. With Price’s Brigade breaking up to his right and Confederate infantry and artillery to his front, he realized he was outflanked and outgunned, and reluctantly ordered a retreat. As Fyffe tried to direct his men back to Grose’s reserve line, a shell exploded nearby, panicking his horse. The frightened animal bucked Fyffe off his back and bolted for the rear, dragging the unfortunate colonel, whose boot was caught in the stirrup. Fyffe’s men, completely demoralized, ran panic-stricken for their lives. Although badly bruised, Fyffe recovered sufficiently to write his wife and mother about the incident shortly after the battle.

With Fyffe’s Brigade routed, the two Confederate right-flank brigades of Pillow and Preston continued forward, pushing back Grose and the remaining elements of Fyffe’s command. On the left, Hanson’s Kentucky troops and Colonel Randall Gibson’s Louisiana Brigade appeared ready to sweep the hill. Things looked grim for the Yankees.

“Colonel, We Have Them Checked. Give Us Artillery and We Will Whip Them!”

Still, Colonel Beatty kept his head and almost stabilized the situation for the Union. After Hanson’s Orphan Brigade smashed Colonel Price’s troops at the base of the hill, Beatty called up his reserve under Grider. Precious moments were lost as Grider’s men grabbed their rifles and fell into position. Up the hill they came, as Price’s fugitives scrambled madly past them in the opposite direction. Grider formed his men at the hill crest. When all was ready, his men fired a volley. Then another. And another.

The telling blows staggered the Confederates. Colonel Grider shouted to Beatty, “Colonel, we have them checked. Give us artillery and we will whip them!” Beatty promised to round up some cannon.

As the Orphan Brigade traded volleys with Grider’s men, a shell exploded, wounding its commander, Brig. Gen. Hanson. Breckinridge raced to his friend’s side in a desperate attempt to stop the bleeding. Then, realizing that Hanson was beyond help, he called for an ambulance to take his comrade away from the carnage. Hanson died of his wounds.

Grider’s Brigade had stopped Hanson, but now the Rebel reserve line under Colonel Gibson moved forward. Indeed, the narrow spacing between the two brigades made it impossible for Gibson’s men not to advance to the firing line where they became so intermingled with Hanson’s troops that all command control of the two brigades was lost. However, the added firepower gave the Confederates an advantage in their stand-up fight with Grider’s troops.

Grider still thought he could slug it out with his gray-clad foes until the promised artillery support arrived, when he noticed his right flank regiment, the 19th Ohio, giving way. Grider attempted to halt its retreat, but the 19th Ohio’s commander, Colonel Charles Manderson, pointed to flank fire he was receiving from Rebels who had crossed Stones River. Grider and Manderson concluded that the brigade should be pulled back to the rear base of the hill. But the Confederates gave Grider no time to re-form. Under intense pressure, his men bolted across McFadden’s Ford to safety.

By now the three Union brigades near the hill had been routed from the field, while the fourth brigade—Grose’s—had been pushed north. The Union battery east of Stones River, the 3rd Wisconsin Artillery, was retreating by sections to the river’s west bank. Even so, the Confederate advance was beginning to lose cohesion. Breckinridge’s attack formation was too tight and his men were now hopelessly intermingled, as brigade and regimental integrity disintegrated.

When Grider’s Federal Brigade pulled back, the mass of Rebels surged forward, the hill now theirs for the taking. Bragg had directed Breckinridge to halt his division once the hill had been captured. Had the Kentuckian done so, his men might have secured the hill using the Duke of Wellington’s famous “reverse slope” tactic, which had helped him win the battle of Waterloo. Wellington had posted his infantry on the rear slope of a ridge, shielding them from enemy artillery fire. But that was not possible now.

Firing wildly and screaming at the top of their lungs, the Confederate troops crested the hill without formation in blind pursuit of the fleeing enemy. Any orders to halt the advance were ignored by the overconfident Rebel soldiers. As Private Ed Thompson put it, “In the madness of the pursuit all order and discipline were forgotten.” Frightened Federals raced down the hill and splashed across McFadden’s Ford, straining to reach the safety of the opposite bank while the Rebels charged down feverishly trying to stop them.

“Myself I Will Surrender, But My Colors Never!”

The final two-gun section of Lieutentant Cortland Livingston’s 3rd Wisconsin Battery entered the stream with the Confederates just 100 yards behind. This section had helped cover the Union retreat, and now Livingston wondered if one or both pieces might be lost to the enemy. Torrents of bullets pinged the water while dull thuds hit the caissons. Several horses went down in the Rebel fusillade, threatening to strand the guns. Under mounting fire the Union artillerymen jumped into the river, cut away the reins from the dead animals, and got the guns to safety.

Farther downriver some Confederates caught up with Corporal E.C. Hockensmith of the Union’s 21st Kentucky (Price’s Brigade) color guard. As Hockensmith was about to enter the ford with the regiment’s colors, he was accosted by a Rebel who ordered him to surrender. “Myself I will surrender, but my colors never!” he shouted, throwing the flag into the water. His comrade, Sergeant J.T. Gunn, seized the colors and splashed across to the other side. In the confusion Hockensmith also made good his escape.

West of Stones River, Maj. Gen. Rosecrans was in a panic. Galloping up to a reserve brigade, he implored, “I beg you for the sake of the country and for my own sake to go at them with all your might. Go at them with a whoop and a yell!”

It was now just past sunset. If Breckinridge could hold his position for another 10 minutes of twilight, Bragg had his hill. But Bragg had not reckoned with Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden’s chief of artillery, Captain John Mendenhall.

Earlier that day, Crittenden, Rosecran’s Left Wing commander, had asked Mendenhall to establish several batteries on the river’s west bank in anticipation of just such an attack. Mendenhall pulled together one of the most lethal artillery concentrations of the Civil War, massing 58 guns on a narrow front, many mounted on the dominating hill northwest of the river opposite its contested sister hill. With the battle reaching its climax and Beatty’s Division in flight, Crittenden turned to Mendenhall and said, “Now Mendenhall, you must cover my men with your cannon.”

Mendenhall waited until the last Union soldiers had safely retreated across the river before giving the signal to fire. Then he let the Rebels have it. Almost 60 Union cannon blistered the disorganized Rebel mob sweeping down the hill. Men fell in heaps. Panic set in. The 16 Confederate cannon north of the recently taken hill tried to answer but were no match for the better-sited, more numerous Federal batteries.

Breckinridge looked frantically for Captain Robertson’s six-gun battery that was supposed to arrive on the hill shortly after its capture, but in vain. Although Robertson sent his smaller battery off to the right, he declined to advance his remaining cannon, claiming (mistakenly) that the Confederate infantry failed to capture this critical elevation. Bragg’s plan to hold the captured hill was coming apart.

In the Confederate lines, all was confusion. Shells seemed to burst among them from all directions. Soldiers who stopped to carry off wounded comrades were themselves cut down. It was as if “the heavens opened and the stars of destruction were sweeping everything from the face of the earth,” remarked one Tennessee soldier. Another suggested that they had just “opened the doors of Hell, and the devil himself was there to greet them.”

Union reinforcements were now at hand. Colonels John Miller and Timothy Stanley spontaneously advanced their Federal brigades across the river and up the hill, supported by remnants of the original defenders. On they charged after the fleeing Confederates, with more Union troops joining in every minute. They retook the hill and still they came.

Captain Wright’s battery attempted to cover the retreat of Breckinridge’s right flank, firing salvos into the lines of Grose’s oncoming Yankees, who had now joined the charge. The Tennessee battery did its best, but the Federals never wavered. As they approached to within 75 yards, Wright keeled over with a mortal wound. Other men and horses went down.

Breckinridge’s chief of artillery, Major Rice Graves, rode up to the battery and took command. “Limber to the rear!” he shouted. Then, thinking better of it, he ordered a final round of double-canister. The guns belched out death to the nearest Yankees and then the men tried to relimber. Too late! The Federals were in among them and only two of the four guns managed to escape.

The Confederates were now streaming back through the woods from where Breckinridge had launched his attack. Unless they stopped, the Yankees would sweep them from the field. Riding into the crisis, General Preston rallied some troops on the Rebel right by vigorously swatting the routing men with his saber. Another knot of soldiers formed around the 20th Tennessee’s Sergeant Battle, who raised the regimental flag after the color-bearer was shot down. Preston praised the sergeant who immediately “seized the colors and bravely rallied the men under my eye.”

On the left, Colonel Joseph Lewis of the 6th Kentucky saw his own color-bearer fall. But Adjutant Samuel Buchanan—noted Lewis—“with the chivalry that ever characterizes him in battle,” immediately picked up the 6th Kentucky’s flag. The colonel called for a volunteer to take the colors and Private Adams bravely stepped forward to receive the flag. As the various regimental flags appeared along the edge of the woods, enough men rallied to the colors to set up a scratch defensive line. They were reinforced by one of the two missing-in-action cavalry brigades and Robertson’s uncommitted six-gun battery.

The Union line approached this final position and halted. The scattered fire from the Rebel units and the gathering darkness deterred any further Union advance. The Federals pulled back to their original lines.

The first battle of the new year was over. With the repulse of this attack (Breckinridge lost 1,500 men, the Federals 700), Bragg decided that a further stand at Murfreesboro was untenable. He would shortly retreat to his Tullahoma, Tenn., position, leaving Rosecrans with a messy but sorely needed victory.

Meanwhile, in the south, the Battle of Stones River raged on long after the fighting ceased. Bragg was furious with several subordinates whose actions, he believed, had cost him a brilliant victory. Prominent on the list was Breckinridge. Not coincidentally, the accused officers thought that Bragg had single-handedly lost Stones River. A postbattle explosion occurred almost immediately.

Beckinridge or Bragg… Who was Right After-all?

In response to adverse newspaper criticism, Bragg circulated a memo to his division and corps commanders asking for their views on the army’s retreat, which his subordinates interpreted as requesting a vote of confidence. Breckinridge joined two other generals in writing Bragg that they no longer trusted his judgment, suggesting he resign for the good of the army. An angry Bragg refused. President Jefferson Davis ordered General Joseph Johnston to investigate the matter, which he did, ultimately supporting Bragg in this dispute.

Now it was Bragg’s turn. Without waiting for the postbattle submissions from his generals, Bragg sent a secret battle report to the War Department in which he faulted a number of officers. In particular, Bragg was upset with Breckinridge’s performance on both December 31 and January 2. As to the January 2 attack, Bragg felt that Breckinridge failed to coordinate the assistance of the dismounted cavalry units on his right flank, despite reminders from Bragg to do just that. In addition, he thought Breckinridge’s overall execution of the attack had been poorly handled, resulting in the loss of unit cohesion as his troops reached the hill.

Breckinridge soon found out about Bragg’s critical report, but his request for a copy was denied. Not until after it was printed in a Richmond newspaper (with Bragg’s help) did Breckinridge get a chance to read the controversial document. Enraged, Breckinridge sent a letter to General Samuel Cooper, Adjutant Inspector General of the Confederacy, in which he complained that the failure of his men to hold the position they had carried “was due to no fault of theirs or mine, but to the fact that they were commanded to do an impossible thing.” Breckinridge then had this letter printed in the Richmond papers, much to Bragg’s chagrin.

The argument as to who was right goes on to this day. While many historians sympathize with Breckinridge, the fact is that the Rebels captured Bragg’s hill despite Breckinridge’s pessimism and tactical mistakes concerning cavalry support and troop disposition. Had Breckinridge kept his men from advancing beyond the hill crest, it is possible they could have weathered Mendenhall’s artillery bombardment for the 10 minutes needed until darkness would have ended the battle.

Regardless of who was right, this personal war did not bode well for the Army of Tennessee. In late May 1863, Bragg got Breckinridge transferred to Mississippi. Bragg had a second division commander court-martialed, and bullied a third into nearly resigning. If Bragg thought he had eliminated or cowed his enemies, he was mistaken. Both corps commanders and many subordinate officers still hated him. Moreover, a need for reinforcements would reunite Breckinridge with Bragg nine months later at the Battle of Chickamauga. While the Army of Tennessee would win its greatest victory at that bloody stream, it could not escape the after-battle bickering that again erupted between Bragg and his generals. The result would be the disaster at Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863, and, finally, Bragg’s own removal from command of the Army of Tennessee.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments