By Ric A. Dias

America’s involvement in World War II was so deep and broad that it demanded that virtually every citizen, farm, and company become involved. Therefore, even a single person, small family farm, or modest-sized company could make a meaningful contribution to the war and thereby have some small degree of global impact.

Such was the case with the Hall-Scott Motor Car Company of Berkeley, California. All but forgotten today, Hall-Scott powered Allied militaries on sea and land to victory with its thousands of high-performance engines, earning the appreciation of fighting men across the globe and some visibility in the public, not to mention record profits totaling millions of dollars. This is all the more remarkable given that just a few years before the war Hall-Scott, mired in the depths of the Great Depression, was dangerously close to bankruptcy. Such was the profound impact of World War II.

Hall-Scott’s origins date back to the early 20th century, when two ambitious young men launched a company to build light rail cars and engines for airplanes and automobiles. Elbert J. Hall, a mechanic and engine builder, had begun to amass a number of impressive successes in spite of his lack of formal education past the seventh grade. Bert C. Scott was a Stanford University-educated son of an influential California businessman who had begun working at his father’s far-flung enterprises. In 1910 the two opened the Hall-Scott Motor Car Company, named after the first product they sold, a gasoline-powered rail car called a motor car. That same year they erected a shop in Berkeley near the shore of San Francisco Bay. The company’s high-performance and cutting-edge designs allowed it to emerge as a leading name in the up-and-coming field of aviation, and it was soon building dozens of engines each year plus a handful of rail cars.

World War I presented Hall-Scott with a sudden flood of orders—several thousand aircraft motors. Domestic production of aircraft measured just hundreds per year before the conflict; then overnight the U.S. government and its allies ordered thousands of planes for the war. Hopelessly overwhelmed, aircraft engine makers yielded to the auto industry to fill the production shortfall. Hall-Scott enjoyed wide recognition in spite of its modest production, leading the U.S. government to order 1,250 of its A-7a motors, and the Russian government to order hundreds more.

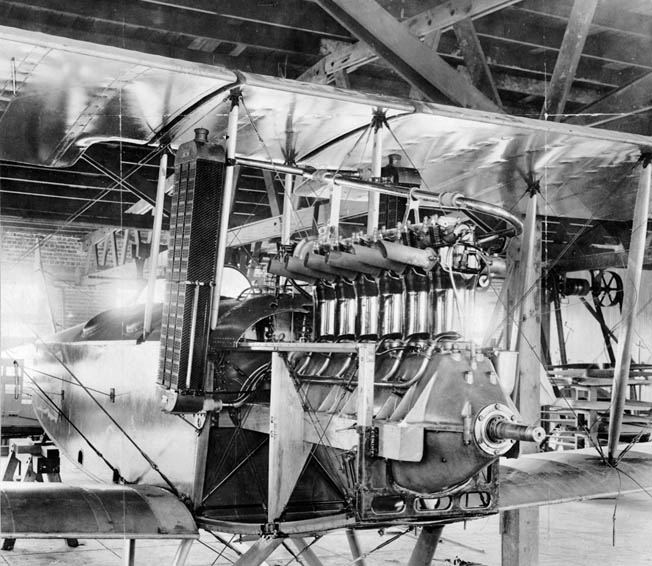

Hall-Scott’s in-line 4-cylinder A-7a stood out because of its aluminum pistons and crankcase, overhead camshaft and valves, and hemispherical (also known as a “hemi”) shaped cylinder heads. Its 606 cubic inches produced 100-110 horsepower, enough to propel a small plane. Hall-Scott quickly added hundreds of men and much production capacity but still could not meet demand, so the company signed a deal with automaker Nordyke & Marmon to build under license another 1,000 A-7a engines. World War I was spectacularly lucrative for Hall-Scott, which registered record production and profits.

With the Great War ending in 1918, Hall-Scott engine production plummeted, as did America’s aviation market, even though innovations continued. Surplus war engines inundated the already contracted market. Pivoting quickly, the small California engine maker introduced a number of new engines for new markets, sold warmed-over World War I models, built engines for other engine makers, and began production of the popular aftermarket Ruckstell 2-speed rear axle for the Ford Model T. In 1925 rail car maker American Car and Foundry (still a rail car builder today, known as ACF Industries) purchased Hall-Scott, giving it, at least in theory, some cover from the ups and downs of the marketplace. E.J. Hall’s engine designs continued to dazzle, and all his postwar designs employed overhead cams, hemi heads, and extensive use of aluminum components. A few models even burned liquefied gas (natural gas, butane, propane, etc.). Hall-Scott enjoyed some successes in the 1920s, but the Great Depression began its stranglehold on the economy late in that decade and slashed engine demand; in 1932 Hall-Scott sold just 145 engines. Could the company survive the hard times?

In 1937, Hall-Scott Motor Car Company, drowning in red ink, was thrown a lifeline from the U.S. government. The threat of war had begun to surface, and so did the demand for marine power. The governments of the United States and its allies had begun shopping for high-speed, gasoline-fueled marine engines, making Hall-Scott a potential supplier.

Hall-Scott had an engine on the shelf representing the leading edge of marine technology that it hoped would interest these motivated buyers. Dubbed the Invader, it was released in 1931, and it was the last engine designed by E.J. Hall before he left the firm.

The all-new Invader displaced 998 cubic inches, arranged its six cylinders in-line, and weighed about 2,000 pounds. It used a cast iron alloy (iron, chrome, nickel) block, aluminum pistons, crankcase, and cam cover, and twin ignition (two distributors and coils, two sets of spark plugs, etc.). The Invader “breathed” well as it had two valves at the top of each cylinder head set in a “cross flow” arrangement, operated by a chain-driven overhead camshaft. The big six belted out 190-275 horsepower depending on features. The long stroke of each cylinder (the bore and stroke measured 5½ by 7 inches) helped it develop 700-750 foot-pounds of torque. It got great press, which led it to become highly desired by rum runners in the closing years of Prohibition. Capable though the Invader was, the Navy needed more engine.

Hall-Scott was in a tough spot. Here finally was the promise of significant demand, but the company could not satisfy the customer’s need for power. While Hall-Scott had a history of developing new designs quickly, its genius co-founder E.J. Hall had left several years before, meaning that an all-new engine was out of the question. With limited time, capital, and in-house talent to develop a new high-output motor, Hall-Scott made a bold proposal: take two Invaders and arrange them at a 60-degree angle to each other around a common crankshaft, making a V-12.

Hall-Scott engineers could handle this assignment, and they soon had a new engine, the Defender. The big V-12 proved to be exactly what the customer wanted, and production began in 1939. The Defender came in two displacements, an early 1,996 cu. in. (twice that of the Invader) version and a later 2,181 cu. in. version (its bore enlarged to 5¾ inches). In fact, the 2,181 engine also came in a supercharged version, which produced substantially more power. Being based on the Invader, the Defender carried many of its essential features with some differences—the V-12 had a two-piece iron alloy block unlike the one-piece Invader block, and both engines had twin ignition, but the V-12 sported a 24-volt system, unlike the 12-volt in the other. Power ranged from impressive to awesome—575 horsepower for 1,996 cubic inches for the V-12, 630 horsepower for the 2,181 cubic inches and a whopping 900 horsepower for the “blown” Defender! By the war’s end in 1945, the Hall-Scott factory had shipped more than 6,500 Defenders.

Perhaps most famously, Hall-Scott Defenders powered craft not in the American fleet, but in the British—the Fairmile A, B, and C motor launches. The government of Great Britain as well as a few Commonwealth nations, such as Canada, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand ran Fairmiles in World War II. The wooden-hulled Fairmiles measured about 110 feet long, displaced about 60-85 tons, and with each ship having two or three Defenders in their engine bays, some supercharged, they could make 20-25 knots. Fairly fast and maneuverable, Fairmiles earned their keep in escort, harbor defense, rescue, sub chasing, and minesweeping and laying duties. According to one British marine writer, Fairmiles “gave outstanding service in many theatres.”

And what of the Invader? The thirst for internal combustion engines was unquenchable in World War II, which was certainly good for any engine maker. Underscoring this importance, the Soviet Union’s Josef Stalin famously and succinctly opined that the war was won by “engines and octane.” But the Invader was more than just an average engine. It was too good to be overlooked, even if the Defender was the first “Scottie” to reach big production numbers. There would be thousands of marine craft that could use a 190-275 horsepower, high-speed, 6-cylinder, gas-burning marine engine, so soon enough tiny Hall-Scott found itself swamped with orders, as it had been decades earlier.

Therefore, just as in World War I, Hall-Scott handed over some production of one of its highly desirable engines to a large automaker for volume output. In 1942, Hudson Motor Car Company of Detroit signed a deal with Hall-Scott to build 4,000 Invaders under license. Hudson manufactures Invaders from 1942 to 1944, making few changes of substance (including adding a heat exchanger and adopting coolant as opposed to sea water for engine cooling) to the Hall-Scott design, which facilitated a quick rollout time. Visually, however, the two motors looked different because Hudson expended some real effort to identify the engine as its own, scrubbing any reference to Hall-Scott from the engine in the process.

This was unlike World War I, when Nordyke & Marmon clearly indicated on the engine that the A-7a was built under license from Hall-Scott. The Hudson name and/or triangle symbol appeared in at least five places on the Invaders they built, on the cam cover, coil cover, gear box, and on the exhaust manifold twice. Hall-Scott left few corporate logos and names on its Invaders. In fact, the notably clean look of the Invader led one reviewer in 1931 to write that it had “sleek” lines. It appears that perhaps Hudson tried to squeeze a bit of glory from its brief association with this fantastic engine.

The Invader, whether built by Hall-Scott or Hudson, found plenty of wartime customers. Invaders powered a handful of landing, patrol, and rescue craft with one or more of the big six-cylinder engines working in the engine bay. A common application was in the U.S. Coast Guard’s picket boats, wooden craft that were often 36 or 45 feet long, capable of 20-30 knots, built by a number of boat yards, from the obscure such as Kirkland Marine to the famous such as Chris-Craft. The U.S. Navy had begun using diesel engines in the 1920s, but there was still call for gasoline-fueled craft in the 1940s, and Hall-Scott was happy to provide power.

There was one more evolution of Hall-Scott’s big marine engine during World War II. In 1940, Hall-Scott released a new land engine based on the Invader, calling it the 400 series. Over the next couple of decades, Hall-Scott fielded a number of closely related land engines, all of which sprung from this first Invader derivative. Like the Defender before it, the 400 shared the Invader’s essential features—iron alloy block, aluminum pistons, crankcase and cam cover, overhead valves and camshaft, cross flow and hemi head, and twin ignition. Hall-Scott bored out the cylinders one quarter of an inch to 5¾ by 7 inches, yielding 1,090.6 cubic inches. Rated at 295 horsepower at 2,000 rpm and 940 foot pounds of torque at 1,350 rpm, the Hall-Scott 400 had plenty of power and a distinctive, deep, rumble issuing from its exhaust. An engine of this size would be of interest to those looking to power large trucks, and in the 1940s that included Uncle Sam. Sales were modest in the first couple of years the 400 was available, but the sales picture changed considerably when the War Department placed a large order for a slightly modified version of the 400, naming it the 440.

The U.S. government mandated a few changes to the 400 to make the 440—a shaft-driven power steering pump, positive crankcase ventilation (P.C.V.), a beefed-up water pump shaft, and an oil filter bypass. The 440 had a lower compression ratio than the base 400, just 5:4:1, so the 440 carried a power rating of 240, about 55 less than the 400. Still, the two engines were very similar.

During World War II the United States relied on gasoline-fueled engines for almost all its land vehicles, unlike its foe Germany which used diesel widely. This American use of gas power included many of its large tow trucks, perhaps the most awesome tow truck of the war being the 440-powered M25/M26/M26A1. San Francisco-based specialty truck maker Knuckey advanced the basic design of this heavy hauler in 1942. Knuckey had the talent to flesh out the basic winning design and, located across the bay from Hall-Scott in Berkeley, its leaders knew of the recently released 400. They included the locally built engine in their proposed truck design.

But Knuckey did not possess the productive capacity to build the truck in number, so that task got handed off to volume vehicle maker Pacific Car and Foundry (still a truck builder today, Paccar is the parent company of Peterbilt and Kenworth). Discussing the truck is made a bit more complicated because of its various names. Technically, the M26A1 was the sheet metal body version of the truck, the M26 was the armored version, and the M25 was the truck when coupled to its trailer (the Fruehauf-built M15). And it had nicknames too, like the colorful “Dragon Wagon” (a nickname shared with other vehicles) and “Pacific,” referring to the maker. For the sake of simplicity, here the truck is referred to as the M26.

Production of the M26 began in Renton, Washington, headquarters of Pacific Car and Foundry, in 1943, but it did not stay there long. Looking around in its own backyard, the company converted buildings at a fairground in Billings, Montana, as the next factory for the giant truck. The M26 performed work back home and on the front lines, with the armored version being more popular in harm’s way. It transported freshly fueled tanks to battle and empty, broken, or damaged tanks away. It hauled trucks, scrap metal, artillery, landing craft, and other boats, captured enemy vehicles, and anything else that it could drag, pull, or load onto its trailer. With its beefy construction and abundant Hall-Scott power, the M26 was rated to haul 40 tons but innumerable times easily pulled much more.

The M26’s job was facilitated by having winches mounted to the truck, one under the front and two behind the cab. There was also a folding boom behind the cab. It also came with a highly adjustable fifth wheel attached to the frame to accommodate a trailer. The truck had three axles, all powered, making it a “6×6.” The Hall-Scott’s power flowed through a transmission with 12 forward and three reverse gears, and a final drive ratio of just 7:69:1. That “low” gearing and chain drive (which delivered power to the rear axles) imposed some limits on top speed, under 30 miles per hour, but attaining a high top speed was not the M26’s performance objective anyway. More of a concern might have been its fuel mileage—the M26 came with a 120-gallon gas tank, but with its 1 to 3 miles per gallon, consumption range was limited.

Pacific assembled about 1,372 Dragon Wagons, and Hall-Scott built about 1,700 of its 440 engines, which led to plenty of the trucks and engines having life after the war. For years following the conflict on both sides of the Atlantic, M26’s pulled houses, ore, lumber, or other cargo, their massive Hall-Scott engines rumbling out their distinctive deep, smooth note.

With the end of World War II in 1945, just as in the wake of World War I, Hall-Scott engine production slid quickly. Short-sighted management at its parent company siphoned off millions of dollars Hall-Scott had earned, money desperately needed to transition to the rapidly changing peacetime market, leaving Hall-Scott weak and vulnerable. The Korean conflict brought another surge of engine sales in Berkeley, but it was small compared to the two world wars—mostly several hundred high-profit Defenders and some bus engines.

The long-struggling ACF finally cut Hall-Scott free in 1954, unable to squeeze any more money from it to cover its own perennial shortfalls. Too small and poorly capitalized to expand in the dynamic postwar engine market, specifically into heavy-duty diesel, management looked for a buyer. Finally, Hercules Motors Corporation of Canton, Ohio, was found in 1958. Fans of war vehicles know this firm because during its 84-year history of engine making (1915-1999) Hercules churned out over two million motors, the biggest single customer being Uncle Sam. But Hercules, like ACF before it, did not invest the capital into Hall-Scott needed to make it competitive, so “Scotties” ceased rolling out of the large Canton factory around 1970.

War, especially World War II, allowed Hall-Scott, a production small fry, to flex its muscles and thrive. World Wars I and II encouraged Hall-Scott to develop new products, to hire more employees, and expand operations. Had the company enjoyed better leadership during World War II, war demand, which made the company bigger and more efficient than it had ever been before, could have positioned Hall–Scott to be competitive in the postwar market for years, perhaps changing the face of American industrial engines.

Ric Dias graduated from the University of California, Riverside in 1995 with a Ph.D. in history. He is a professor of history at Northern State University in Aberdeen, South Dakota. Dias has written on Kaiser Steel Corporation and the Cold War. With former company employee Francis Bradford he wrote Hall-Scott, The Untold Story of a Great American Engine Maker, published by SAE International in 2007.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments