By Eric Niderost

On August 16, 1866 a mysterious ship appeared off the western Korean coast and began to steam up the Taedong River. Korea, then called Choson, had adopted a policy of strict isolation from the outside world, so foreign ship sightings were a rare occurrence. The “Hermit Kingdom” was virtually unknown to the West and preferred it that way. Foreign trade was forbidden and, save for some traditional ties to China, diplomatic contact with other countries was nonexistent.

The ship was the General Sherman, owned by American businessman W.B. Preston. Preston was well aware of the risks involved, but the opportunity to open untapped markets proved too tempting to resist. He leased his ship to the British firm of Meadows and Company; they would provide the cargo, and he would transport it to Choson. If successful the joint venture would be lucrative, with the promise of greater profits to come.

The General Sherman was an American vessel, but its passengers and crew were international. Besides Preston, the ship’s captain and chief mate were Americans. There were two Britons aboard: George Hogarth and missionary Robert Thomas. Around 13 Chinese and three Malays rounded out the crew.

Reverend Robert Jermain Thomas was an Anglican cleric who joined the crew as its official interpreter. Thomas had picked up a few words of Korean from Korean Catholics exiled in China. The 26-year-old reverend burned with missionary zeal, hoping to save souls and spread the Gospel in a “heathen” land. Filled with Western goods and the message of an alien faith, General Sherman was all the Koreans hated about the outside world.

A series of misunderstandings and miscalculations on both sides, salted by prejudice and cultural differences, soon led to tragedy. The General Sherman incident set off a chain of events that culminated in a short but bloody clash between Korean and American armed forces. This battle, which occurred in June 1871, is sometimes called America’s “first Korean War.”

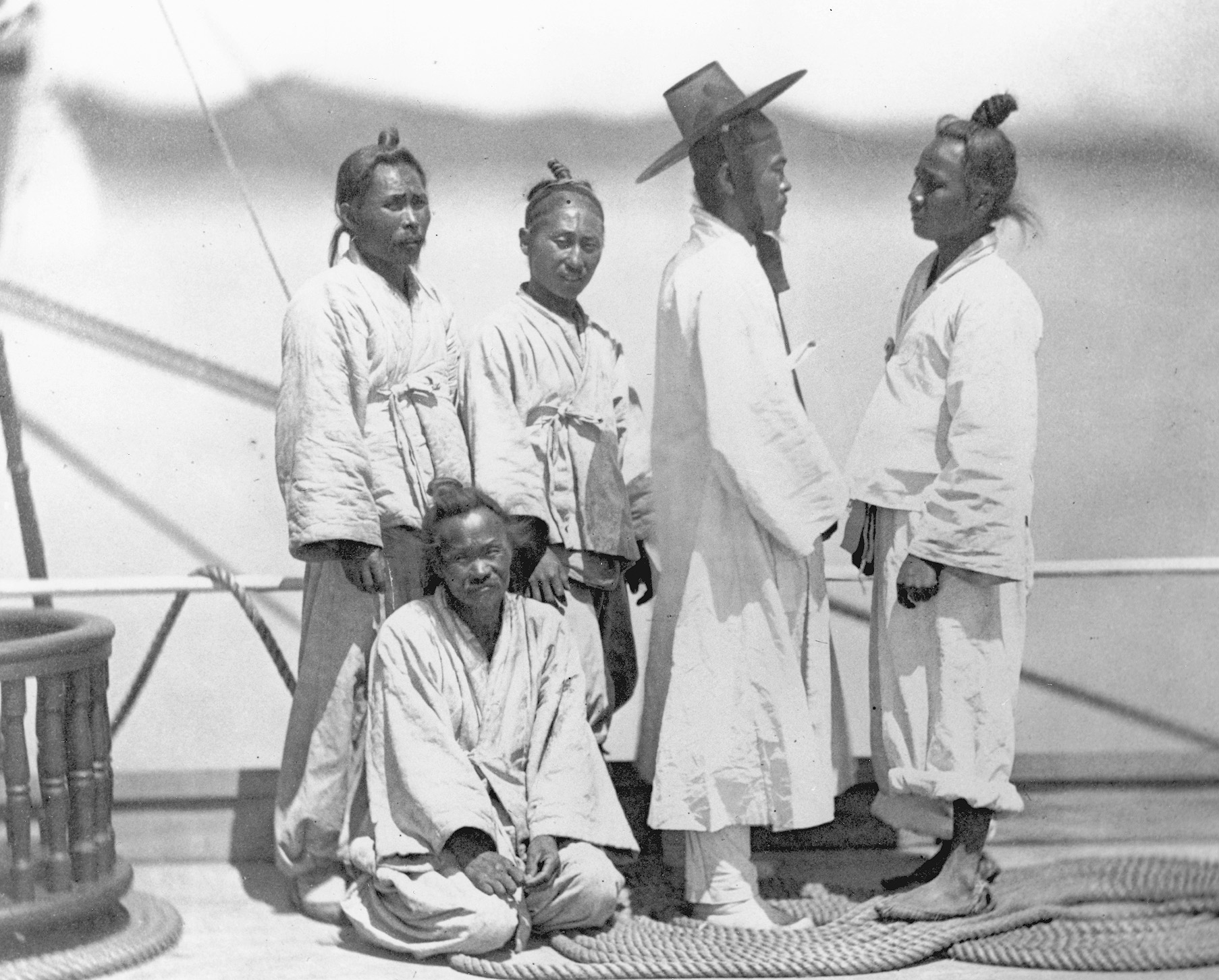

General Sherman’s movements were closely observed. A Korean account notes that “In the year Pyeng-in [July 1866; the Koreans were using a lunar calendar] a black foreign schooner was sighted in the Taedong River. The ship dropped anchor at the Keupsa Gate on the border of Pyongan and Hwanghae provinces.” Provincial Governor Pak Kyu-su immediately dispatched emissary Jung Dae-sik to scout out the foreigners’ intentions. Jung was cordially received, and his practiced eye quickly scanned the ship and the makeup of the crew.

Reverend Thomas came forward as interpreter, but since his Korean was far from fluent some of the Chinese crew helped by writing Chinese characters, a language Koreans readily understood. Thomas wore a sword and pistol, but it was not uncommon in those days for men of the cloth to be armed in dangerous circumstances. Nevertheless, the martial display seemed to contradict his professions of peace and goodwill. Seeking to allay Jung’s suspicions, Thomas declared that the ship was from the land of “Mi-guk” (the United States) and its primary purpose was trade.

The reverend must have noted Jung’s careful observations, or perhaps he saw skepticism etched in the Korean’s face. Thomas admitted General Sherman “looked like a warship,” but insisted it was a peaceful merchant vessel desiring naught but trade. Jung probably wasn’t convinced; in point of fact, the ship was formerly the U.S. Navy gunship Princess Royal. Jung replied that Choson did not engage in foreign trade, and that only King Kojong himself could change the isolationist policy. According to Korean accounts, Thomas became abrasive, raising his voice and acting almost as if he were running the ship.

Nothing was resolved in the meeting, though to prove their hospitality the Koreans sent provisions to the ship, which were gratefully accepted. After Jung’s departure the ship weighed anchor—they had been instructed to stay put—and continued up the Taedong. They stopped along the river at Ju-yong-po, Song-san-ri, Sah-po-gu, and Poh-ri. Local officials did all in their power to gently persuade the visitors to leave, but the words fell on deaf ears.

Thomas was the first Protestant missionary to set foot in Korea, and he lost no time in preaching to villagers who had gathered in curiosity to see the strange ship. The reverend extolled the superior qualities of Protestantism, though all forms of Christianity had been banned by the Choson government. The common people proved receptive to his message; at one point, “500 Bibles were handed out,” and “the ship was in danger of tipping over due to so many Koreans being aboard.” Thomas was no doubt gratified, but his well-meaning actions were foolhardy in the extreme. Thousands of Korean Catholics had been killed over the years, and in 1866 Choson was in the midst of a major persecution.

General Sherman’s progress upriver was impeded by the Crow Rapids at Manyongdae. The ship dropped anchor just below the rapids on August 27. That night torrential rains fell in the eastern mountains, the runoff flooding into the Taedong. The rain-swollen river enabled General Sherman to cross the rapids with little difficulty. Apparently Preston and ship’s master Captain Page felt the river’s engorged condition was its normal level, an assumption that was to prove fatal.

General Sherman anchored off Pyongyang, the provincial capital (now capital of North Korea), still hoping to start trading. Deputy Commander Yi Hyon-ik of the Pyongyang Military District visited the ship, bearing some eggs and a personal message from Governor Pak Kyu-su. The governor made it clear he considered the foreigners a major problem since “you insist on trading with us, which is forbidden.” The official had no recourse, the missive continued, but to “consult the king and let him decide what to do with you people.”

The events of the next few days are shrouded in controversy. In later years the Choson government, under increasing Western encroachment, tried to hide or at least obscure its part in the General Sherman affair. It was said that General Sherman crew members ran amok, firing on native boats and even kidnapping women. These stories may be true, or they may have been fabricated to provide justification for Choson’s subsequent actions.

All sources agree the immediate trigger of hostilities was the kidnapping of Korean official Yi Hyon-ik. Early on the evening of August 28, six General Sherman crew members manned a small, blue launch and rowed upriver. They encountered a small junk carrying Yi and another official named Ahn Sang-hop. Suddenly the General Sherman sailors boarded the junk and took the Koreans prisoner. One account claims the American ship’s crew found plans that detailed a Korean attack on General Sherman, though this is an allegation that cannot be confirmed or disproved.

The kidnapped Yi Hyon-ik remained a hostage aboard the American ship. Why did the General Sherman’s crew launch an attack on the junk in the first place? The truth will probably never be known with absolute certainty.

When word spread that the foreigners had captured an official, Korean indignation knew no bounds. Crowds gathered along the shore, shouting and gesticulating wildly as they demanded Yi’s immediate release. Thomas tried to calm the crowds by telling them the matter would be settled when the Americans “entered the walled city of Pyongyang,” but his words only further enflamed public fury.

Captain Page decided it was time to leave, but the river had dropped to its normal levels. The General Sherman was trapped, and to make matters worse the ship ran aground on a sandbar. Since King Kojong was only a teenaged boy at the time, his father the Taewongun (“Great Prince of the Court”) ruled in his name. The Taewongun sent a message to Governor Pak that was unequivocal: “If they do not leave, have them killed.”

The Korean military prepared to engage General Sherman, even though the American vessel was heavily armed. Long centuries of isolation had left the Korean Army a pitiful anachronism. Matchlock guns and bows and arrows were the norm, and some cannon dated from the 16th century and earlier.

Accounts vary, but probably the Koreans fired first, inaugurating a tough four-day battle. General Sherman’s cannon frightened the local populace with their thundering reports, but at first the crew deliberately fired over Korean heads to avoid casualties. When the Koreans pressed their attack General Sherman raked the shore with shrapnel, described by Korean observers as “showers of deadly steel fragments.”

The General Sherman crew worked their guns with a will, loading, running out, and firing in rapid succession. A turtleship (kobukson)—a type of vessel that had seen service in the 16th century under Korea’s national hero Yi Sun Shin—was brought out to engage General Sherman. Essentially a war galley, the kobukson’s guns were so hopelessly outdated they could make little impression on the American ship’s sturdy sides. The antique warship was withdrawn after a few futile and thoroughly inadequate attacks.

So far the General Sherman had more than held its own. Yet the ship was still held fast on the sandbar, and there was little chance the crew could free it. Time was on the Korean’s side. Korean ingenuity came to the rescue when their military technology was found wanting. Sergeant Pak Chung-wun ordered three boats to be tied together near Pyongyang’s East Gate. Once secure, they were loaded with firewood and liberally coated with sulfur and saltpeter. Two long tow ropes snaked ashore and provided some guidance for these scratch-built “fireboats.”

The trio was set ablaze and launched against the General Sherman. The fires extinguished before they could reach their objective. Undaunted, Sergeant Pak prepared a second trio of burning boats, but this time the General Sherman’s crew managed to fend it off. The Koreans prepared another set of fireboats, and the third attempt proved to be the charm.

The boats crashed into the American ship, tongues of orange-yellow flames greedily consuming its wooden decks, masts, and spars. Soon the whole ship was ablaze, coils of thick, black smoke ascending to the sky. The crew fought courageously, but General Sherman was a raging inferno beyond redemption. In the confusion, Sergeant Pak stole aboard the ship and rescued Deputy Yi.

There was nothing left to do but abandon ship or burn to death. Apparently some chose self-immolation, the General Sherman becoming a giant funeral pyre. Others swam ashore and tried to surrender, smiling and gesturing in a vain plea for mercy. It was futile; the populace was so enraged by the losses they had sustained during the battle that the foreigners were slaughtered on the spot. Some apparently were beheaded, others beaten to death.

According to one story, Reverend Thomas stood at the bow of the burning ship until the last possible moment, throwing Bibles overboard so that Holy Scripture would not be consigned to the flames. Shouting “Jesus, Jesus!” he finally dived off and swam ashore. Captured, he was bound and later executed. Not one person aboard the General Sherman survived. The ship burned to the waterline, its iron ribs protruding above the river “like posts driven into the ground.” A few cannon were recovered and displayed as trophies, and the anchor chain hung from Pyongyang’s East Gate tower.

The Korean government rejoiced in the apparent destruction of the marauding “barbarians.” In recent years China and Japan had been forced to open their doors to Western powers; Korea felt pride in having resisted foreign encroachment.

In the fall of 1866 the French sent a punitive expedition to Kanghwa Island, an island that guarded the approaches to the Han River and Seoul, the Choson capital. French Catholic missionary priests had managed to enter the country but were discovered and brutally executed. The executions were the start of a bloody persecution that eventually claimed the lives of 8,000 converts. The French had come to seize the island, blockade the capital, and teach the Korean government the error of its ways.

In the end it was the French who were taught a lesson. The French took Kanghwa, but accomplished little else. At Chongjok, French marines were repulsed when attacking a mountain fortress, sustaining casualties of almost 50 men. With winter approaching and the local populace aroused, commanding French Admiral Pierre-Gustave Rose decided to withdraw. His forces were simply too small to make any impression.

After the French departure, the Koreans again celebrated their victories against foreign invaders. The victories had been real, but on one level, illusory. While interest in Choson was rising, Europe and the United States had other, more pressing, concerns. The French, for example, were actively engaged in Southeast Asia, laying the foundations of what would be French Indo-China. Choson was a sideshow—but it would not remain on the periphery for long.

The American government first received word of General Sherman’s fate from Father Felix-Clair Ridel, a Catholic missionary who had accompanied the French punitive expedition. He received a report that a Western ship had been destroyed at Pyongyang. Further investigation revealed it was the General Sherman.

American diplomats stationed in China discounted the reports as unfounded rumors. Shipwrecked sailors were usually well treated in Choson, a policy known as yuwon chiui or “goodwill to strangers.”

They were treated with kindness and compassion, their wounds tended, clothes and food freely provided. For example, on June 26, 1866 the American ship Surprise had been wrecked off the coast of Pyongan. The castaway crew had been cared for, then turned over to Chinese officials at Uiju on the Sino-Korean border for repatriation.

American officials could not reconcile this apparent contradiction—why save the crew of the Surprise and slaughter the crew of the General Sherman? In 1867 the USS Wachusett sailed from Yantai, China, on the Shangdong Peninsula to try to find some definitive answers. Once off Choson, initial contacts seemed to confirm the ship’s demise. Some reports, backed by rumors, seemed to suggest that at least some of the General Sherman’s crew was alive and held captive.

The corvette USS Shenandoah was dispatched to Choson in April 1868 to obtain more information on possible survivors. Captain John C. Febinger failed to get any information, and the mission produced nothing. Up to this point the Koreans had been given every benefit of the doubt, the Americans hesitating to resort to a show of force. Now, there was going to be more of an emphasis on European-style “gunboat” diplomacy.

In 1870, Washington decided to take decisive action. Frederick Low, the new U.S. Minister to China, was authorized to sail to Choson and treat with the Korean government directly. Low was directed to secure a treaty for the protection of shipwrecked sailors. If a commercial treaty could be obtained, so much the better, but the emphasis was on helping seamen, not forcing Choson to open its doors to the outside world.

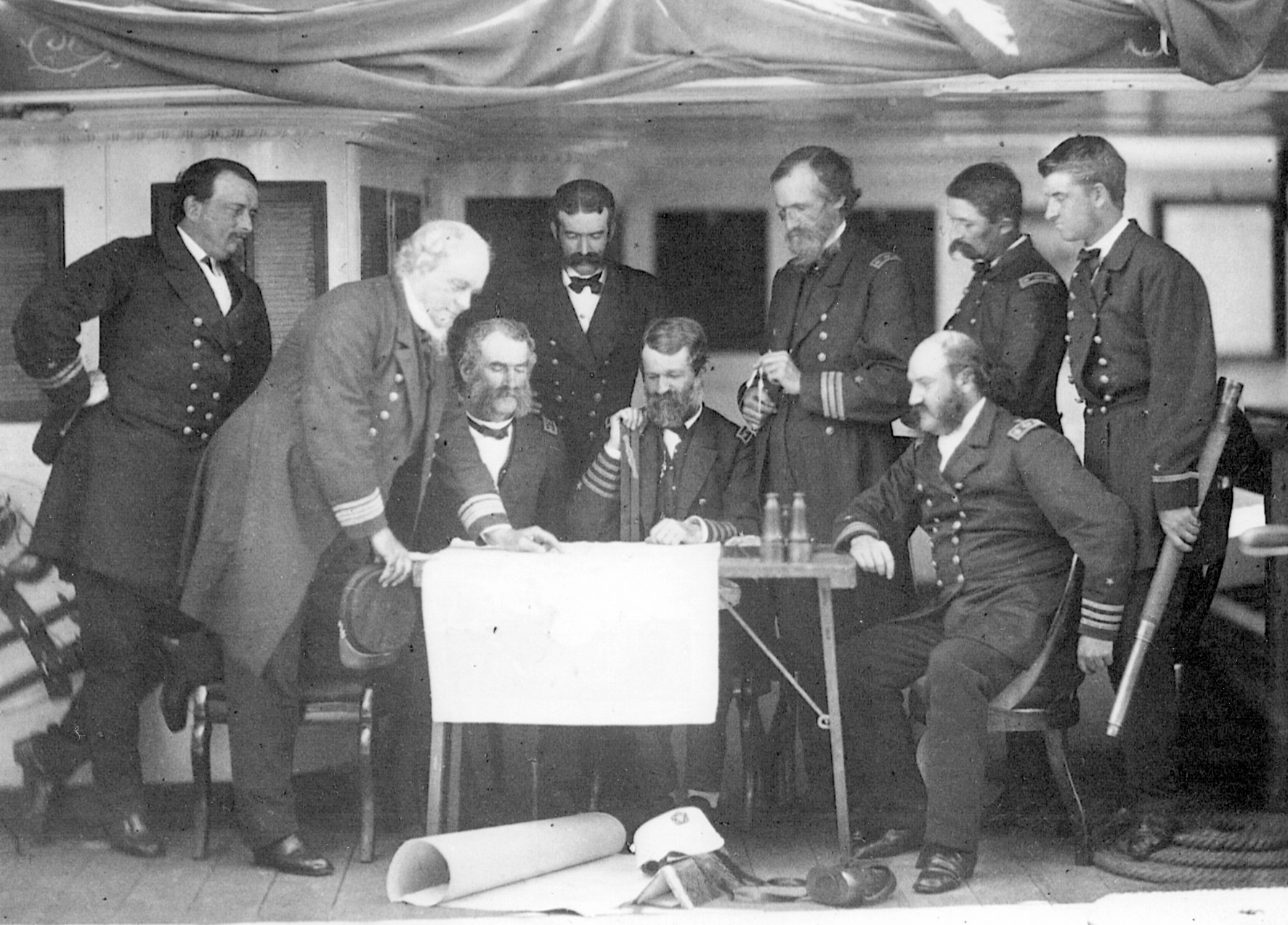

It took about a year to make the necessary preparations for the expedition. The force consisted of five warships: the steam screw frigate USS Colorado, the steam sloops Alaska and Benicia, and the gunboats Monocacy and Palos. The USS Colorado served as the flagship of Rear Adm. John Rogers, commander-in-chief of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet. Minister Low and his diplomatic staff lodged aboard Colorado.

The Colorado was a warship of Civil War vintage, but the Alaska and Benicia were the newest additions to the U.S. Navy, commissioned in 1869. There were 1,230 Marines and U.S. Navy “bluejackets” in the expedition, enough to mount limited offensive actions, but certainly too few to take on an entire nation.

On May 30, 1871 the American squadron dropped anchor off Isle Boisee, now Jayak Island. They were not far from Kanghwa, the fortress-studded isle that guarded the mouth of the Han River and Seoul. Kanghwa is separated from the mainland by a twisting ribbon of water then called the Salee River. Salee, French for salt, is a literal translation of the Korean Yeom Ha (Salt River), but the name is misleading. Actually, it’s a channel known for its treacherous currents and powerful tides. The name is tinged with unintentional irony; in 19th-century parlance, the phrase “salt river” meant misfortune.

Three Korean envoys arrived on May 31 and were cordially welcomed aboard USS Colorado by Low’s acting secretary, Edward B. Drew. Drew spoke Mandarin Chinese, a language readily understood by the Koreans, so there was no communication barrier to overcome. The secretary was disappointed to learn these visitors were low-level functionaries with no credentials for serious negotiations. Low refused to meet them, since dealing with such obviously unimportant individuals was a waste of time and an affront to his dignity as Minister Plenipotentiary.

The Americans told the trio of envoys that they wanted to make soundings of the “river” and careful surveys of its deeply indented shores. The intention was peaceful exploration, and the Koreans were assured that survey parties would not be a threat to native lives and property. The Korean delegates didn’t seem to raise any objections to the American proposal.

Kanghwa Island was rich in history, a traditional refuge for Korean royalty in times of upheaval. In the 13th century King Kojong had lived on Kanghwa during the Mongol invasions. The French punitive expedition had briefly occupied Kanghwa in 1866, and after they departed the Taewongun lavished much care and money upgrading and strengthening defenses. The Americans would find Kanghwa Island a much tougher nut to crack.

The southern end of the island was defended by the twin fortresses of Choji Dondae and Choji Jin. About a mile farther north one encountered Dukjin fortress, its high stone walls studded by cannon. But the most formidable fortification in the area was locally known as kwangsungbo, or “the citadel.” Kwangsungbo was the main fortress, but it had two outworks. Sondolmok Dondae was a smaller fort that perched on a small, conical hill about a hundred yards from the citadel. The other outwork was a redoubt that was reached via a long, snaking, stone causeway. Perhaps because it featured such a long “neck,” the redoubt was dubbed “Yong-do-Dondae” or “Dragon Head Fort.” The Americans, no less descriptive, called it “elbow fort.”

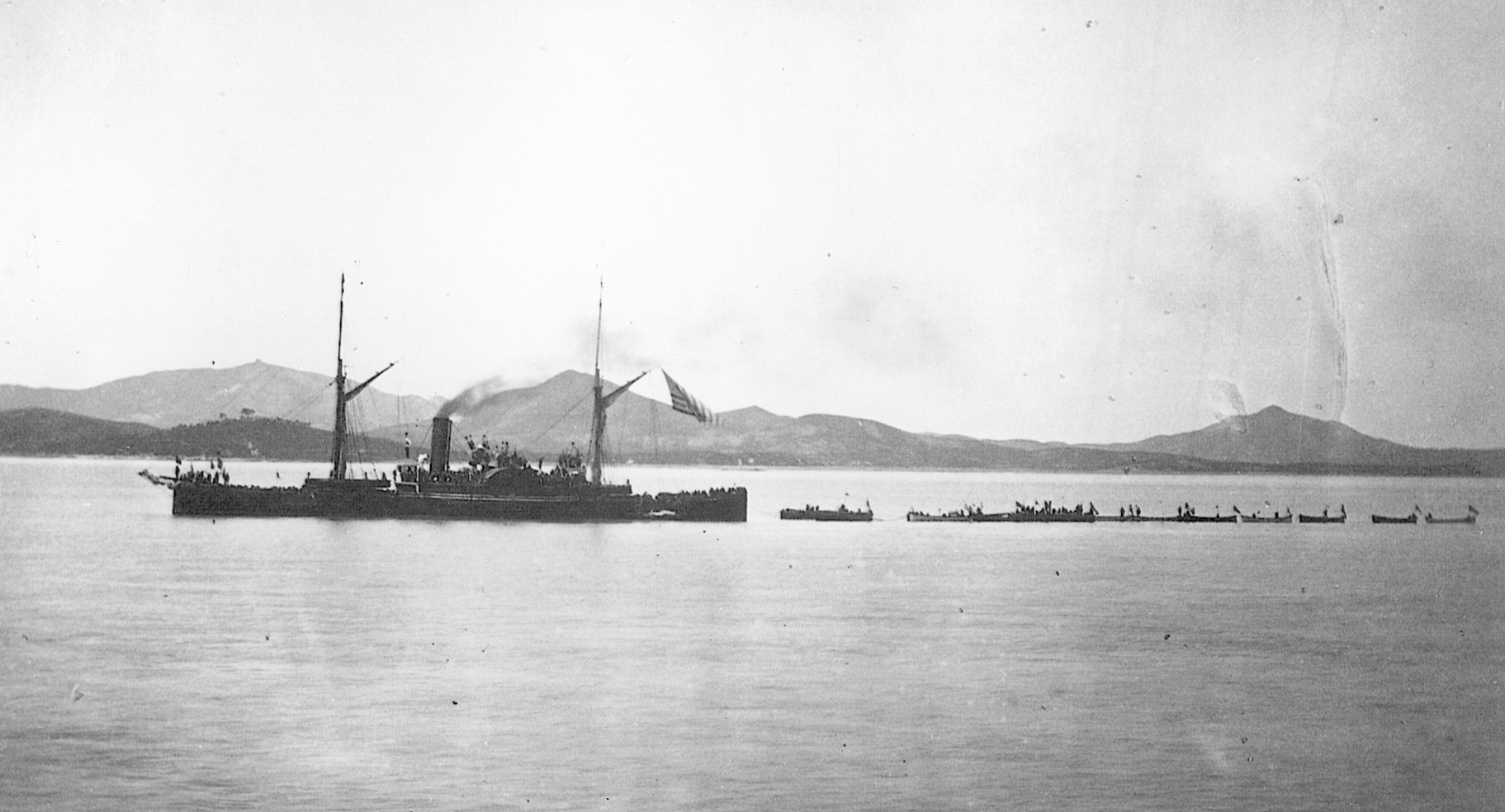

The survey party left the main anchorage at noon on June 1 and proceeded north, their tentative probings of the “Salee River” carefully observed by Koreans ashore. Four steam launches took the lead, followed by gunboats Monocacy and Palos. In theory these vessels were ideally suited for the task. The USS Monocacy was a sidewheel gunboat armed with 9-inch Dahlgen smoothbore cannon, while Palos carried two 24-pounders fore and aft. Both vessels were of shallow draft, ideal for exploring unknown waterways.

Sailors stood at the bows of the steam launches and threw lead-weighted lines into the blue-gray waters of the Salee, carefully measuring each sounding and calling out their findings. The survey party approached a bend in the channel, a place where the Salee skirted past a fist of land called Sondolmok, not to be confused with the fort of the same name. Several little islands rose above the waters, narrowing the channel and making navigation that much more difficult. The Americans could see Kwangsungbo fortress in the distance, but there seemed to be no sign of any unusual activity.

Suddenly the Yong-do-Dondae battery opened fire on the launches, its cannon springing to malevolent life with a thunderous roar. Black cannon snouts poked out of embrasures, then disappeared in gouts of smoke and flame.

The Korean batteries at Tokp’o and Trokchin joined in the bombardment, forcing the hapless launches to endure a hurricane of shot. Great geysers of white water marked each near miss, wetting decks and crews, but fortunately the vessels escaped major damage. The launches managed to slip past the gauntlet of fire, enabling the Monocacy and Palos to come up and engage the forts. Accurate American gunnery silenced the forts and killed at least one Korean artilleryman.

The tide swept Monocacy and Palos farther up the channel, but unfortunately the former hit a rock that ripped a hole in its hull. The leak was hastily repaired without much trouble. The survey party vessels now had to retrace their steps in order to get back to the main squadron. This was accomplished without further incident.

Admiral Rogers remarked later that it was fortunate that Korean marksmanship was poor. The survey vessels had endured about 15 minutes of intense bombardment, yet had emerged relatively unscathed. Only two sailors, James M. Cochran and John Somerdyke, had been slightly wounded. Although the Americans had escaped significant injury, they were indignant that they had been attacked—at least in their view—without provocation. Admiral Rogers and Minister Low both agreed that the situation called for a military response.

The Koreans would not be allowed to get away with such aggressive behavior; American honor was at stake. No, the Koreans would have to be taught a salutary lesson, but in the interests of international goodwill they would be given a chance to explain or apologize. Seoul would be given 10 days to make amends; if no apology was forthcoming, punitive operations would commence.

The 10 days passed without any apology from the Taewongun or the Korean government at large. The Taewongun did send a brief note to Minister Low justifying Korean actions, declaring the Americans had penetrated an important defensive zone. The Korean leader rejected all notions of foreign trade, saying seclusion was a “settled principle” maintained by “our forefathers for five centuries.”

The Koreans were far from contrite, and used the 10-day lull to strengthen Kanghwa defenses. General Uh Je-yeon was appointed deputy commander of the Chinmu regiment on the island, and soon several hundred other troops were dispatched as reinforcements. Four thousand kun (one kun equals 1.32 lbs) of gunpowder, 30 crossbows, 900 arrows, and 30 pieces of artillery were also sent to bolster defenses.

News of the June 1 clash gave a new sense of urgency to Korean preparations. General Uh recruited professional game hunters (p’osu), men who tracked Siberian tigers in the remote mountains of Pyongan province. These men were tough and won a formidable reputation against the French in 1866.

In accordance with official State Department wishes, Low and Rogers agreed that a “humane” policy would be adopted in pursuing punitive action against the Koreans. The offending forts would be the only targets; villages and towns would remain unmolested. This is in sharp contrast to the French invasion of 1866, when many coastal villages were heavily damaged by naval bombardment.

Operations were to begin at 10 am on the morning of June 10. The initial landing would be on the southern end of the island. Two steam launches took the lead, followed by Monocacy and Palos. The Monocacy’s armament was bolstered by the addition of two more 9-inch guns transferred from the flagship. Palos was heavily burdened, towing a long string of 22 boats loaded to the gunnels with the landing force. There were 651 men in the boats, of which 105 were U.S. Marines.

The Chonji forts opened fire, but were quickly silenced by Monocacy’s 9-inch shells. Nature seemed more of a threat than Korean gunfire; a fringe of mudflats some 200 feet wide greeted the Americans as they came ashore. Weighed down with weapons and equipment, many sailors and Marines sank down into the glutinous brown muck to their knees. The landing literally bogged down, the men losing shoes, gaiters, and even pants legs as they pulled out from the mud’s viscous embrace.

Walking in mud was one thing; moving artillery in the soggy “pudding” quite another. Twelve-pounder howitzers were designed for such amphibious operations, but the guns soon sank up to their axles. It took superhuman effort to manhandle them to firmer ground.

Captain McLane Tilton and his Marines formed a skirmish line and fanned out to protect the landing. A few scattered shots greeted them, but the Leathernecks sustained no casualties. Tilton cautiously led his men to the Choji fortresses, but found them abandoned. Once the Navy bluejackets arrived, the Marines moved off to reconnoiter the area. In the meantime, the main landing party swarmed over the forts, dismantling 12-foot walls with picks and axes. Cannon were spiked, or thrown down the cliffs to the channel below. In honor of their accomplishment the Choji forts were renamed “Marine Redoubt.”

The afternoon sun was hot, and rivulets of sweat ran down the faces of the laboring men. Night was coming on so a camp was established near a Korean cemetery, the distinctively round hillocks of each grave seeming to mimic a military encampment. A picket was established to guard against night attack. Sure enough, the Koreans attempted a raid at about midnight, but were soon driven off. The next morning the landing party moved on to Dukjin fortress, located on a bluff about a mile from Choji/Marine Redoubt.

The Monocacy shelled Dukjin, softening up its defenses should an assault be deemed necessary. Once again Marine Captain McLane Tilton went forward with his men, only to find Dukjin abandoned. The deserted fort suffered the same fate as its predecessors. The artillery found in these forts was not merely obsolete; it was positively antique. The Korean guns were a hodgepodge of various calibers, from small breechloading bronze pieces with one- or two-inch bores, to 32-pounder “giants.”

Later, when these guns were examined and their casting dates deciphered, the Americans were amazed. Some of the cannon bore the Korean equivalents of 1607, 1665, and 1680. Two pieces dated from 1313. The Americans had been attacked by the oldest active coastal defense system in the world.

The next phase of the operation was going to be the most difficult of all. Just ahead, perhaps two miles farther north, was the kwangsungbo complex of forts and batteries. The bulk of the Korean forces were in Sondolmok Fort, but the other posts were manned as well. If the Americans attempted to take this final series of defenses, the Koreans would resist.

The march resumed early on the morning of June 11. The terrain was seamed by deep ravines punctuated by steep hills that undulated across the landscape like ocean waves. The sun grew hotter as the day wore on, a blazing orb that made the march a trek through hell. Its searing rays penetrated sweat-soaked wool uniforms until a number of men succumbed to sunstroke.

The artillery had the worst of it, trying to drag the 12-pounder howitzers up steep inclines. Companies of infantry were detached to pull artillery tow ropes attached to gun carriages, the sappers filling gullies with brush to ease the torturous passage.

Korean troops suddenly appeared on the left flank, threatening to get behind the Americans and cut off their line of retreat. To prevent this from happening Lt. Cmdr. Wheeler was put in command of three companies and five howitzers to act as rear guard. Around 11 o’clock the footsore column finally gained the hill opposite Sondolmok Fort. They sheltered behind its reverse slope while making final preparations for the assault.

When the signal was given, the Marines and bluejackets would have to run down the hill, cross a ravine, then scramble up the step sides of Sondolmok Fort hill. Sondolmok was small but well built; its stone walls rose above the hill in an almost seamless fashion, the natural and the man-made merging to produce a sheer precipice.

Monocacy had sailed up the channel just off Sondolmok and began a preliminary bombardment of the fortress. The shelling was intense and accurate; soon, snaggle-toothed gaps appeared in the once-pristine walls. The rear guard’s howitzers were also close enough to add their support, the booming reports and ear-splitting blasts a rising chorus of destruction. Moments later Korean troops attacked the rear guard; these assailants “blazed away at us with their gingals or matchlocks, their black heads popping up and down the while from the grass.” A howitzer shot or two soon ended the affair.

In the meantime, the artillery fire slackened then ceased altogether, signaling that the time for an assault was imminent. The Korean garrison began to chant, a thousand voices blending into a deep and melancholy dirge. It was a chilling sound, likened by one American officer to a “howling of dogs.” Some Americans felt it was a death song similar to that practiced by the Plains Indians back home. Most probably it was not a death chant but the Hogok, loud weeping and lamentation for the dead—in this case, casualties of the naval bombardment.

Military flags still waved proudly from the Korean battlements, symbols of strength and defiance. Navy Lieutenant Hugh McKee, one of the leaders of the assault force, told his friend Lieutenant Bloomfield McIlvane, “Mac, we have to capture one of those flags.” Within minutes they would be given that opportunity. When the breeches were considered practicable the assault force moved off in column. The men first ran down the hill that had sheltered them, gravity and its steep sides giving them an added, and no doubt welcome, momentum.

The fort parapets blossomed with sheets of smoke and flame as the garrison opened up with matchlock fire. Matchlocks are crude, ineffective weapons even in skilled hands, and most of the hail of lead passed over American heads. The assault force crossed the ravine, then scrambled up the fort hill to attempt an escalade. As they drew nearer, Korean musketeers stood exposed on the parapets to draw a better aim. Such recklessness had a high cost, and Marine bullets tumbled them from the walls. All Americans remarked on the garrison’s determination and exemplary bravery.

Lieutenant McKee outdistanced his men, a conspicuous figure in his officer’s frock coat that featured gold straps perched on each shoulder. McKee bounded up on the parapet, sword in one hand and pistol in the other. He fired his revolver twice, then jumped into the fort interior, momentarily disappearing from view. Marines and sailors gained the parapet a few seconds later, rushing into the fort with bayonets fixed.

Korean soldiers fought with matchlocks, clubbed muskets, and spears. Lieutenant McKee was impaled on a Korean spear, staggering back with a mixture of shock and surprise from the blow. Lieutenant Commander Schley shot his assailant down, but McKee was mortally wounded. A Marine had secreted a small flag on his person, and as soon as he gained the parapet he waved the diminutive Stars and Stripes in token of victory.

A bloody hand-to-hand fight ensued for the next 15 or 20 minutes, the Koreans finally giving way to superior tactics and weaponry. Some Koreans escaped, but many chose to die at their posts. Hundreds of dead and wounded Korean soldiers clogged the fort, the air heavy with the rotten-egg stench of powder smoke. General Uh fought as courageously as his men, refusing to retreat or surrender. He was killed by Marine Private James Dougherty.

The Korean commander’s personal flag was called the su-ja-ki. An impressive yellow banner some 12 feet square, it featured a large black Chinese character su, meaning “commander in chief.” Private Hugh Purvis and Corporal Charles Brown rushed to the flagpole in the center of the fort and took the su-ja-ki as a trophy. It hangs today at the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis.

Korean casualties stood at 243 dead. Only 20 prisoners were taken, most of them badly wounded. The Americans lost three dead, including Lieutenant McKee, and 10 wounded. The captured fort was renamed “Fort McKee” in honor of the fallen naval officer. No less than 15 Medals of Honor were awarded for the action; Private Purvis and Corporal Brown were among the recipients.

The Americans had won the battle, but lost the diplomatic war. Because the Korean government refused to negotiate, the American expedition had no choice but to weigh anchor and depart Choson shores. The American force was simply too small to take on an entire nation, however technologically backward. Admiral Rogers conceded that only an expeditionary force of “5,000 men” could take Seoul and force the Taewongun to come to terms.

The Taewongun was elated when he heard of the American departure, interpreting this as a great Korean victory. “Western barbarians foully attack!” the Taewongun exclaimed in a proclamation, then added, “Should we not fight?” The United States simply lacked the will to mount a major effort in Asia. Westward expansion was the primary focus in the 1870s, American Indians more concern than distant Koreans. Thinking that he had bested the French in 1866 and the Americans in 1871, the Taewongun persisted in his isolationist policy. It was to produce fatal results, because it left Choson/Korea vulnerable to a rapidly modernizing Japan a few years later.

Eric Niderost, a frequent contributor to Military Heritage, is a community college professor in Hayward, California.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments