By Eric Niderost

In the winter of 1942-1943, the Allies had every reason to believe that they were on the verge of total victory in North Africa. It had started in November 1942, when German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s much-vaunted Panzerarmee Afrika was decisively defeated by the British Eighth Army at the Second Battle of El Alamein. Rommel’s setback was not merely a defeat but a full-scale rout, and surviving German and Italian units were forced into a headlong retreat through the burning deserts of northern Libya. Rommel seemingly was trapped between American forces advancing to block his retreat and British forces in hot pursuit to his rear.

The Axis disaster at El Alamein coincided with Operation Torch, three coordinated Allied landings in French North Africa at Casablanca, in Morocco, and at Oran and Algiers, in Algeria. Operation Torch, approved after a series of sometimes acrimonious discussions between President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, was designed to open a second front to augment the valiant Russian efforts against Nazi Germany in the East. Owing to French sensibilities, the landings were mainly an American effort. The Americans came ashore on November 8 waving the Stars and Stripes and were immediately met with fierce resistance from French colonial troops loyal to the collaborationist Vichy government back home. At Oran, British naval cutters Walney and Hartland were sunk by French fire, costing the Allies an additional 445 unnecessary casualties before the political situation was sorted out. At Algiers, a five-day delay in the proceedings was finally resolved, and Vichy commander Jean Darlan reluctantly agreed to end colonial resistance to the Allied landings.

The need for continued cooperation from Darlan was eliminated—along with Darlan—when the admiral was assassinated on Christmas Eve by a Free French intelligence operative. The way was clear for a concerted drive on the grievously wounded Panzerarmee. For even the gifted Rommel, the end seemed near. In two years of unremitting desert warfare, he had performed wonders, earning him the respect and admiration of friends and foes alike. Allied air and naval forces often reduced his supplies to a trickle, and he was usually outnumbered by his British foes. German Führer Adolf Hitler, preoccupied with his ongoing Russian campaign, failed to appreciate the strategic significance of North Africa. Many of Rommel’s fellow officers were old-school aristocrats bred in the Prussian tradition, and to them he was little more than a middle-class upstart.

Morale Low, Casualties High

In spite of all these difficulties, Rommel had won a number of brilliant victories and came within an ace of capturing the Suez Canal, key to the entire Middle East and Great Britain’s lifeline to India and East Asia. Rommel led from the front; he was a masterful tactician and strategist imbued with an offensive spirit that swiftly exploited enemy weaknesses. Rommel had become larger than life, a man christened with the enduring sobriquet “the Desert Fox.” Even his enemies gave him grudging admiration.

In the fall and winter of 1942-1943 the fox seemed at bay, surrounded by a host of Allied hounds. Panzerarmee Afrika was a broken reed, a mere shadow of its former self. About half of Rommel’s command had been killed, wounded, or taken prisoner, and 450 tanks and 1,000 guns were taken or destroyed. Rommel himself was exhausted and increasingly prone to periods of ill health. He was plagued by headaches, and to make matters worse, he came down with a painful bout of nasal diphtheria.

Yet Allied hopes of total victory turned out to be premature. The Torch landings, besides giving the green American troops an exaggerated idea of their own prowess, had finally aroused Hitler from his lethargy on North African affairs. Enraged, he occupied southern France and began to pour reinforcements into Tunisia. German and Italian troops were easily ferried into Tunisia from Sicily, only one night’s voyage distant. General des Panzertruppen Hans-Jurgen von Arnim’s Fifth Panzer Army was the main element in the eleventh-hour surge of Axis troops.

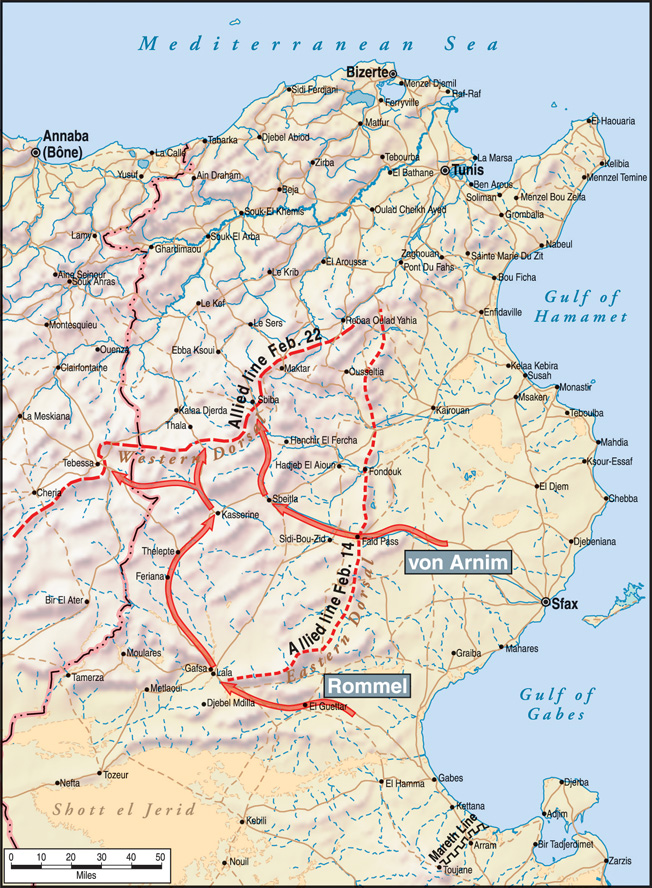

By January 1943, Rommel had retreated some 1,400 miles across the spine of northern Africa, and his men’s morale was as low as their casualties had been high. Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery’s Eighth Army took Tripoli—Rommel’s main supply base—on January 23, but the triumph was short-lived. The Allied pursuit was literally bogging down, with heavy winter rains turning Tunisia’s yellowish soil into a sea of primordial muck. Rommel retained hopes of linking up with von Arnim’s forces and effecting an orderly withdrawal of all German forces from North Africa. But to do so, he believed that it was necessary to inflict a stinging defeat on the newly arrived Americans before they could complete a fatal encirclement with the British Army along the old French fortification line at Mareth on the Libya-Tunisia border.

His counterpart, American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, was supreme commander in the Mediterranean Theater, a job that demanded tact as well as diplomatic skills. Eisenhower performed both tasks admirably, but he was too often handicapped by political considerations in the early stages of the campaign. In early February he had to drop everything to attend the famous Casablanca Conference and consult with Roosevelt and Churchill on Allied plans. He finally left the conference on February 12 and immediately took a tour of the Tunisian front.

Rushing the Kassarine Pass

Meanwhile, Rommel received word that he was to be recalled to Germany for rest and recuperation. There was to be a reorganization of his forces; Panzerarmee Afrika would be designated the German-Italian Panzer Army and placed under the command of Italian General Giovanni Messe. But the Desert Fox did not want to leave Africa on such a sour note. Rommel wanted to redeem himself and restore his reputation, tarnished after El Alamein and what to him was an ignominious retreat. Rommel was a keen observer and a strategic opportunist. He saw weaknesses in the American forces, whose troops were green and largely untested. Rommel began to think in terms of an offensive, using the Fifth Panzer Army and, he hoped, a rested and re-equipped Panzerarmee Afrika. If Rommel could smash through the inexperienced American line, he could rush through Kasserine Pass and take Tebessa, a major Allied supply hub. There was also a possibility that Rommel could sweep north and take the remaining Allied forces—now facing von Arnim’s Fifth Panzer Army—in the flank and rear.

If and when his plan was approved, Rommel knew that he would not have to worry about Montgomery’s Eighth Army advancing in his rear. The old French fortifications at the Mareth Line would hold Montgomery in check—at least for a time. Rommel planned to man the Mareth Line with his infantry, reserving his more mobile armored forces for the proposed attack. The American II Corps would be Rommel’s primary target. It was commanded by Maj. Gen. Lloyd Fredendall, a man full of bravado and macho posturing. He had a habit of tough-guy talking that alienated subordinates and sometimes made his orders unclear.

Rommel argued for an immediate offensive, and at first it seemed like a tough sell. On paper, German operations in Africa were controlled by the Italian Comando Supremo, although Rommel generally had a free hand. Now the Desert Fox had to deal with Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, who had been appointed Oberbefehlshaber Sud (Commander in Chief, South), an area that encompassed the whole Mediterranean. Meeting with Kesselring and von Arnim at a Luftwaffe airbase at Rhennouch, midway between Tunis and Mareth, Rommel presented his plan. It was a frosty meeting. Rommel and von Arnim knew each other well, but in their case, familiarity did not breed affection. As the well-born son of a Prussian general, von Arnim resented Rommel’s parvenu status and heroic image, which he considered overdone. Kesselring did not like Rommel any more than von Arnim did, but he was inclined to give Rommel one last chance. Rommel’s plan was approved, although scaled down. Instead of one major offensive thrust through the mountains, there would be two separate attacks. Von Arnim would launch an offensive codenamed Operation Frühlingswind (Spring Wind), while Rommel would attack to the south of von Arnim under the designation Morgenluft (Morning Air).

The Lay of the Land

Tunisia, a fist of land thrusting out into the Mediterranean Sea, is a region of arid plains and formidable mountain ranges. The Western Dorsal and Eastern Dorsal are two offshoots of the Atlas Mountains that run roughly parallel to the coast, 70 miles inland. These two rocky “backbones” are all but impassable, save for a number of passes that cut through their rugged slopes. Allied units had already advanced through the Western Dorsal and established a front line that touched the western edge of the Eastern Dorsal. The northern part of the line was held by the British First Army under Lt. Gen. Sir Kenneth A.N. Anderson. Americans felt uncomfortable around Anderson, considering him a prototypical dour Scotsman. Like most British officers, he liked to closely supervise the tactical plans of subordinates, which to American sensibilities felt too much like uninvited interference. Anderson’s main focus was the northern segment near the coast, where he felt the decisive showdown with the Germans ultimately would take place. The center of the Allied line was held by Free French troops of the XIX Corps d’Armee. They were largely colonial troops of varying quality, poorly equipped until the Americans gradually gave them more up-to-date weapons. The officers were almost stereotypes of Gallic pride, always eager to show their courage and quick to take offense at perceived slights to French honor.

But it was the southern end of the Allied line that gave Eisenhower the most worry. As soon as he was able to break away from the Casablanca Conference, he traveled to make an inspection of the II Corps. Eisenhower was appalled; in some respects, things were even worse than he had imagined. The problems started at the top. Fredendall had established his headquarters an incredible 80 miles to the rear of the front line in a nearly inaccessible ravine. He seemed obsessed with air attack, and he had a swarm of 200 engineers busily digging a network of underground bunkers for himself and his staff. As Eisenhower remarked later, “It was the only time during the war that I ever saw a higher headquarters so concerned over its own safety that it dug itself underground shelters.” Not wanting to embarrass Fredendall, Eisenhower had merely cautioned his corps commander not to stay too close to his command post, adding the less-than-inspiring observation that “Generals are expendable just as is any other item in an army.” Fredendall did not take the hint.

Eisenhower also visited the oasis village of Sidi Bou Zid, near the western entrance of the Faid Pass that sliced through the Eastern Dorsal. Axis forces were on the other side of the mountain chain, and who knew what their plans might be? If they decided to mount an offensive, Eisenhower saw only too clearly that the American forces were ill prepared to resist. The troops were green, which could not be helped, but they were also lackadaisical. Defensive minefields had yet to be put down, although Americans had been in the area for at least a couple of days. There were always excuses and assurances that such tasks would be done tomorrow.

Some troops had not even bothered to dig foxholes in the desert terrain. Eisenhower pointed out with disgust that the Germans always dug minefields, placed machine guns, and had reserve troops standing by, but the Americans seemed content to throw their backpacks on the ground, stack their rifles and grenade belts in an untidy heap, and head off to the nearest village tavern for some unearned rest and relaxation. A recent circular letter from Eisenhower to his subordinate commanders, cautioning them “to impress upon our junior officers the deadly seriousness of the job,” had gone unheeded.

A Late Assessment from Eisenhower

Although Eisenhower did not know yet where the Germans would launch a major attack, he knew in his bones that one was coming soon. Confirmation of a sort had come from his chief intelligence officer, British Brig. Gen. Eric Mockler-Ferryman, who had assured Eisenhower that the Germans were planning to attack the British and French positions on the northern flank of the Allied line. American Brig. Gen. Paul Robinett, whose Combat Command B (CCB) of the 1st Armored Division was temporarily attached to the British sector, had vigorously disputed this claim, telling Eisenhower that his own tanks had penetrated all the way across the Eastern Dorsal without running into a single advanced enemy position. Robinett had tried to warn Anderson as well, but the Scotsman had airily dismissed his warnings. Eisenhower was inclined to believe Robinett, and he ordered Fredendall to gather his scattered armored units into a mobile reserve ready to confront any German attempt to break though the mountain passes. Eisenhower’s reasoning was sound, but already too late. It was the evening of February 13, and for the Americans casually guarding the southern line, time had run out.

The Offensive Begins

The first part of the German offensive—Operation Frühlingswind—began in the early morning hours of February 14. The 10th Panzer Division smashed through the Faid Pass, using a blinding sandstorm as perfect cover. At the same time, the veteran 21st Panzer Division raced through the mountains to the south of Sidi Bou Zid, then turned north, intending to link up with the 10th Panzers. The Nazis’ initial targets were a pair of hills, known locally as djebels, that guarded the road from Faid to Sebeitla. After encircling these Allied-held outposts, von Arnim’s troops would capture Sidi Bou Zid itself.

The two hills in question, Djebel Lessouda and Djebel Ksaira, flanked Sidi Bou Zid and seemed like good defensive positions—on paper. Fredendall had placed infantry units on the tops of each hill, intending them to slow the German advance until American armor could deal with them. Unfortunately, there were too few men on the hills, and they were too far away from each other to provide mutual support. The hilltop infantry was reduced to helpless observers of an American debacle swiftly unfolding on the plains far below.

Colonel Thomas D. Drake of the 165th Infantry Regiment, 34th Division, was situated on Djebel Ksaira, watching the spectacle below with growing frustration. Drake phoned the command post at Sidi Bou Zid, warning them that some American artillery was already showing signs of panic. The commanders in the rear refused to believe it, insisting that the men were only shifting positions.“Shifting positions, hell,” Drake responded. “I know panic when I see it.”

“Let’s Get the Hell Out of Here”

Nearby, the Americans on Djebel Lessouda were also powerless to intervene in any meaningful way. A strong southwesterly wind had smothered all sounds of the German buildup the previous night, and Major Norman Parson’s patrolling G Company had run headlong into the lead elements of the 86th Panzer Grenadiers and 7th Panzer Regiment that morning, getting themselves knocked out of commission and losing all radio communications with Djebel Lessouda. Once the sandstorm lifted, Lessouda’s commander, Lt. Col. John Waters, could plainly see what he estimated to be at least 60 German tanks and numerous other vehicles. Waters was the son-in-law of Maj. Gen. George S. Patton, who had not yet become famous as one of America’s best military leaders. Waters earlier had cautioned his men after their easy victory over the French during the Torch landings: “We did very well against the scrub team. Next week we hit the Germans. When we make a showing against them, you may congratulate yourselves.” His words would prove to be prescient.

American armor moved forward to confront the growing threat. Colonel Louis V. Hightower’s force—two companies of tanks and about a dozen tank destroyers—rumbled out of Sidi Bou Zid to attack the 10th Panzer head-on. Hightower and his inexperienced crews were brave but badly outnumbered and were facing a well-prepared enemy. German 88mm artillery scored hit after hit, turning American armor into flaming coffins one by one. The M-4 Sherman tanks used by the Americans, which for some reason they had nicknamed “Honey,” were given a more mocking, if accurate, nickname by the Germans—“Ronson,” after the cigarette lighter, because they burst into flames so readily.

Hightower’s force was facing Mark VI Tiger tanks, new and powerful additions to the German arsenal that had a firing range twice as long as the American tanks. The combination of German artillery shells and long-range tank fire proved too much for Hightower’s men, who tried in vain to conduct a fighting retreat in the face of heavy odds. Hightower’s own tank was knocked out, but not before he had destroyed four panzers. Hightower and his crew managed to escape the burning hulk and sneak away from the battlefield amid the smoke and dust. (“Let’s get the hell out of here,” Hightower said reasonably.) They were the lucky ones—only seven of Hightower’s 51 tanks survived the defeat, however. The other 44 American tanks were lost, and Sidi Bou Zid had to be abandoned. American Brig. Gen. Raymond A. McQuillin, commanding Combat Command A (CCA) within Sidi Bou Zid, fell back to a new position seven miles southwest of the town, while German Colonel Hans Georg Hildebrandt took possession of the stronghold.

A Disastrous Armored Charge

Before long, 21st Panzer linked up with 10th Panzer, and they moved quickly to consolidate their gains. The 2,500 American infantrymen on the two hills were now cut off, literally islands of resistance in a German sea. Drake still stubbornly held Djebel Ksaira and Waters held Djebel Lessouda, but chances of a successful breakout were diminishing by the hour. Meanwhile, back at his headquarters, Fredendall refused to allow Waters and Drake to escape while there was still time. Fredendall’s stubbornness was compounded by faulty assumptions and bad intelligence. British General Anderson, Fredendall’s superior, was convinced that the German drive on Sidi Bou Zid was merely a diversionary attack for a larger blow farther north. Allied intelligence also insisted that there was only one Panzer division in the south. As a result, only one tank battalion—Lt. Col. James Alger’s 2nd Battalion, 1st Armored Regiment—was sent to deal with the Germans and rescue the Americans trapped on the two hills.

Alger’s equipment was good—mainly M-4 Sherman tanks—but his tactics were poor, and his men were brave but inexperienced. They did not realize they were going to face not one but two Panzer divisions. The result was an almost textbook example of what not to do in desert armored warfare. Alger’s counterattack began on February 15. The 58 Shermans came forward at a high rate of speed, which meant that huge dust clouds marked their passage. So much dust was kicked up that crews were blinded, and the thick plumes made them easy to spot and target. The American tanks rolled forward in a rough V-shaped formation, with tank destroyers on the flanks. It was like an old-style cavalry charge, but the Germans were about to bring the Americans into the 20th century.

German artillery hidden amid olive groves opened fire, and German tanks attacked Alger’s flanks. Before long the Americans were trapped, engaging veteran Mark IV Tigers at point-blank range. Only four American tanks managed to escape the debacle. The entire battalion was wiped out, with 55 tanks lost and some 300 men dead, wounded, or captured, including Alger, who was taken prisoner. Divisional commander Maj. Gen. Orlando Ward was left literally in the dark about the attack’s outcome. So much smoke and dust were kicked up in the battle that he could only report to Fredendall, “We might have walloped them, or they might have walloped us.” It was soon clear who had done the walloping.

Realizing at last that rescue was impossible, Fredendall gave belated permission for the two trapped hilltop forces to try to break out on their own. Drake led his men down the slopes of Djebel Ksaira under the cover of darkness, but he soon encountered German tanks, which surrounded him and his 600 men in a large cactus patch. Drake tried to bluff his way out, shouting “Go to hell!” when the Germans demanded surrender, but it was no use. He and his men were soon made prisoners.

Waters and many of his command were also taken prisoner, with perhaps one-third—about 300—out of the original 900 getting back to Allied lines. The whole Allied line was in jeopardy, and the Germans seemed on the brink of a major victory. There was nothing left to do but fall back to the next line of defense—the Western Dorsal chain, some 50 miles away. With luck, the Western Dorsal passes—particularly the vital Kasserine Pass—could be held and the German offensive stopped.

A Chaotic Retreat

The retreat to the Western Dorsals proved to be a nightmare. The battered II Corps had been badly defeated, and with that defeat came a crisis of confidence. Fredendall, who had pulled back to the town of Kouif, complained to Eisenhower: “At present time, 1st Armored [is] in a bad state of disorganization. Ward appears tired out, worried and has informed me that to bring new tanks in would be the same as turning them over to the Germans. Under the circumstances [I] do not think he should continue in command. Need someone with two fists immediately.” Eisenhower had no intention of removing Ward, but he did send a trusted lieutenant, Maj. Gen. Ernest Harmon, to advise Fredendall “during the unusual conditions of the present battle.”

The roads leading west were jammed with fleeing American vehicles, providing easy targets for rampaging German Stuka dive-bombers swooping down from the sky like avenging furies. Eisenhower, who had left before the battle to return to his headquarters at Constantine, Algeria, began shuttling reinforcements to Ward and McQuillin at Sbeitla, an old Roman crossroads 13 miles northwest of Sidi Bou Zid. “Our soldiers are learning rapidly,” Eisenhower reported to Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall. “I assure you that the troops that come out of this campaign are going to be battlewise and tactically efficient.” Moreover, said Ike, the men were “now mad and ready to fight. All our people, from the very highest to the very lowest, have learned that this is not a child’s game and are ready and eager to get down to business.” It was the best face he could put on the looming disaster.

Code Name Sturmflut

In the meantime, Rommel’s Operation Morgenluft had swung into action south of von Arnim’s so-far-successful Frühlingswind. Rommel met with little resistance, and the field marshal was delighted when the Allied airfield at Thelepte was captured with 50 tons of much-needed fuel and lubricants on the morning of the 17th. But the offensively minded Rommel was disturbed by the fact that von Arnim had not fully exploited his successes at Sidi Bou Zid. Von Arnim argued that he could not advance too far because the supply and fuel situation was iffy at best. Rommel was unconvinced.

Rommel wanted to assemble all available Axis forces for a major thrust through Kasserine Pass. Once though the pass, he could take the major Allied supply depot at Tebessa then push on to the Tunisian coast at Annaba (Bone). With any luck, this northwestern thrust would get him behind Anderson’s British First Army, which could be trapped and annihilated at the Germans’ leisure. Rommel’s bold plan depended on immediate action, but his superiors had to approve it first. At least a day was wasted while Kesselring and the Italian high command mulled it over. In the end, the proposal was given the green light under the code name Sturmflut (Hurricane), but it was a somewhat vague, watered-down version of the field marshal’s initial proposal. Under Sturmflut the Axis forces were to push through Kasserine Pass, then start heading in the direction of Le Kef. Compared with Rommel’s original plan, this was a shallow, halfhearted envelopment of Allied forces—but something was better than nothing. All Rommel knew for sure was that he had the green light, and he acted accordingly. The battle for Kasserine Pass was about to begin.

Fredendall’s urgent task was to defend the Western Dorsal barrier against Axis attack—but where was Rommel going to strike? Kasserine was not the only pass that cut through the mountains, so he spread his forces thin to cover all possibilities. Some British and French units came down to help, but the Allied defenses were still weak. Kasserine was initially defended by Colonel Anderson Moore’s 19th Combat Engineer Regiment, a unit whose main duties were construction, not fighting. Fredendall summoned Colonel Alexander Stark of the 26th Infantry and told him to hold the pass. “I want you to go to Kasserine right away,” Fredendall said, “and pull a Stonewall Jackson.” It was typical of Fredendall when issuing orders to make colorful quips, phrases that contained little real substance. Stark arrived at Kasserine Pass on February 19, just as the Germans were beginning their attack in hopes of a breakthrough.

“The Place is Too Hot!”

Kasserine Pass was (and still is) a rocky defile that narrowed to about 1,500 yards. Once past that bottleneck, Kasserine’s western entrance broadened to a wide basin that split into two roads. One road led west to Tebessa and the vital Allied supply base, while the other trailed north to the town of Thala. The Americans had artillery positions in place at both roads, ready to concentrate fire when the enemy emerged from the narrow Kasserine bottleneck.

February 19 was miserable for all the combatants. A cold wind chilled soldiers to the bone, and drenching rains added to the discomfort. The Germans tried to slip though American positions under the cover of a thick enveloping fog, but their unavoidably noisy movements were detected. American artillery, tank destroyer, and small-arms fire soon sent them packing. The German attack on Kasserine was led by General Karl Bulowius, who seemed to hold such contempt for the Americans that he kept ordering direct assaults. About 3:30 pm, Bulowius sent the Germans forward once again, this time backed by Italian tanks. They ran into American minefields placed there earlier by the long-suffering engineers and were stopped dead in their tracks.

Bulowius, still confident, waited for the coming of night. The Germans would infiltrate American defenses under cover of darkness, slipping through the hills and ridges that formed Kasserine’s shoulders. These phantom raiders were partly successful, unnerving green units already shaken by the heavy fighting. On the Tebessa road, one company of engineers broke and ran, and a group of German infiltrators in stolen uniforms captured 100 Americans. Panic became contagious, and the situation was so fluid that some officers did not know what was going on. American soldiers, individually and in small groups, abandoned their positions and sought safety in the rear. Even some forward artillery observers abandoned their posts, shouting, “The place is too hot!” American infantry reinforcements and British tanks arrived during the night and stabilized the situation.

Breakthrough of the Kasserine Pass

Saturday, February 20, dawned cold and wet, but the Germans had still not achieved the desired breakthrough. Rommel had arrived, and was not happy with what he saw. Time is everything in war, and Rommel knew that he did not have much left to achieve victory. Montgomery’s Eighth Army was still far to the east, but was fast approaching the Mareth Line. “Those fellows are all too slow,” he complained to aides when he found the 10th Panzer Division resting comfortably near Sbietla. When division commander Brig. Gen. Fritz von Broich explained awkwardly that he was waiting for an infantry battalion to attack first, Rommel exploded. “Go and fetch the motor cycle battalion yourself, and lead it into action too,” he ordered. He was tired of listening to lame excuses from his less-daring subordinates.

Rommel’s presence had a positive effect, and for a time it seemed as if the heady days of 1941-1942 were back again. The Germans employed a relatively new weapon, Nebelwerfer, multiple-rocket launchers, which the Americans quickly dubbed “Screaming Meemies” because of the terrifying sounds they made in flight. The 10th Panzer Division finally moved through the pass in force, only to be met by a handful of British Valentine and Crusader tanks and American tank destroyers positioned in roadblocks. The British and Americans fought valiantly, but the issue was never in doubt. The Allied armor, outnumbered and outgunned, was destroyed in detail. Twenty-two American tanks and 30 half-tracks littered the valley floor.

The Germans were through the main part of Kasserine Pass and seemingly on the point of a major breakthrough. Once on the western side of the pass, Rommel faced two roads—one going southwest toward the Tebessa supply center, the other going north to Thala and then on to the town of Le Kef. Le Kef was the nominal objective of Sturmflut, but Rommel was lukewarm about enveloping the British First Army. In the end, the field marshal sent forces down both routes. Kampfgruppe DAK (Deutsches Afrika Korps) went up the road toward Tebessa, while the 10th Panzer traveled north toward Thala and Le Kef. By now, more and more Allied units were being redeployed and coming into the battle, stiffening resistance. Colonel Paul Robinett’s Combat Command B of the 1st Armored Division gave the Germans a rough time on Tebessa road. Accurate tank and artillery fire stalled the Axis drive, and American infantry pushed the Germans back and actually recaptured some equipment that had been lost earlier. Even Rommel admitted that the enemy had counterattacked “very skillfully.”

German forces driving down the northern road enjoyed greater success against the Allied forces defending Thala. British Brig. Gen. Charles Dunphie’s 26th Armoured Brigade fought hard but their equipment could not match German tanks. British Crusader and Valentine tanks were outranged and outgunned, and their armor was thinner. Soon the desert landscape was littered with knocked-out British armor, their flaming hulls sending thick black coils of smoke into the sky. Dunphie pulled back to a ridge threee miles south of Thala, having lost 38 tanks, 28 guns, and 571 men captured. British defenses had crumbled, and the road to Thala was open.

The Real Victors at the Kasserine Pass

Axis forces might have been victorious, but they were not unscathed. German and Italian personnel losses had been relatively light, although some individual Italian units had been decimated. The main problem was a crippling shortage of fuel and ammunition. More and more Allied units were coming into the fight, some from as far away as Morocco, and Axis advances—once so promising—had slowed to a crawl or been stopped in their tracks. On February 21, American Brig. Gen. LeRoy “Red” Irwin arrived at Thala with three artillery battalions and two cannon companies—a total of 48 guns in all. Despite having made a grueling four-day, 800-mile forced march from western Algeria, Irwin’s men immediately moved into place to support the exhausted British.

The next morning, the 10th Panzer was met with a thunderous Allied artillery barrage. Von Broich, having already endured a dressing down by his field marshal, a nerve-wracking attack at the front of his motorcycle battalion, and a brutal hand-to-hand melee with stiff-backed British defenders, called off the advance. After reading an intercepted message from the British commander declaring that “there is to no further withdrawal under any excuse,” Rommel realized that the Allies intended to stop him where they stood, or die trying. Down to his last 250-300 kilometers’ worth of fuel, Rommel conceded the obvious. He called off all further offensive actions and withdrew to the east. The Desert Fox’s last gamble had failed.

In their first extended combat of the war, the Americans had sustained losses of 6,600 killed, wounded, or captured—more than 20 percent of their entire personnel. In a sense, however, the U.S. Army was the real winner at Kasserine Pass. The North African campaign was a painful but necessary testing ground for American forces, enabling them to gain experience and fine-tune weapons and tactics. Incompetent or mediocre commanders such as Fredendall were weeded out and replaced. In their place, more competent and aggressive commanders such as George S. Patton were groomed for larger things. American training on the whole was sound, but armored theory had to be rethought and reforms introduced. Rommel had shaken the Americans out of their cocksure complacency, hardening them for a long, drawn-out struggle. Thanks to the hard lessons so painfully learned at Kasserine Pass, American forces would be better prepared when they mounted their next major invasion—on the coast of Normandy, France, on June 6, 1944.

I would note that Kesselring was generally supportive of Rommel and had hoped to urge him to continue the offensive. He came through at Alam Halfa with Luftwaffe petrol to allow the gamble.

It would have been interesting if Rommel’s very efficient former Afrika Corps commander Gen. Nehring had remained in von Armin’s position. He seemed to be much like Rommel and they seemed to get on well. And he’d successfully saved Tunis for the Axis forces early on in the Run for Tunis. If he’d encouraged Rommel to continue to focus on Tebessa, it might have led to a full Allied retreat into Algeria. Wouldn’t necessarily have prevented failure at Medenine but one never knows. And Hitler was considering at least under pressure from Guderian whether the Kursk attack should be abandoned for a defensive stand with more troops sent to Africa/Italy. Could have been interesting.

I think that, in the photo labeled as “Field Marshal Erwin Rommel surveys the battle near the wreckage of a British Bren gun carrier”, the vehicle that appears near Marshal Rommel is not a Bren Gun Carrier, but an L3 / 33 or Carro Veloce CV-33.

Sadly, Fredendall was given another star after this debacle, then sent to a training command in the USA. In my opinion, he should have been reduced to his permanent rank of brigadier general and stowed somewhere out of the way, if not outright retired.