By Robert A. Rosenthal

It was late November 1943, almost two years after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into World War II. The Allied leaders, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Josef Stalin, were meeting for the first time in Tehran, the capital of Persia. The agenda was complex, but the primary topic was resolution of the strategy to defeat Nazi Germany.

Churchill advocated attacking from the Mediterranean, the soft underbelly of Europe as he called it. Stalin, on the other hand, was emphatic about giving the invasion of France priority over all Allied plans for the coming year. He desperately needed a second front to take the pressure off his diminishing army. He insisted that the Italian campaign be limited and rejected any Balkan venture. Furthermore, he promised that once Germany was defeated he would join the war against Japan. With Roosevelt and American military leaders agreeing with Stalin, it was decided that Operation Overlord, the invasion of France, would commence in the spring of 1944.

The Question of the South Pacific

And so it did. On June 6, 1944, more than 100,000 Allied troops and 7,000 ships stormed the beaches of Normandy in the largest amphibious invasion in history.

Although it was decided in Tehran that the war in Europe was paramount and that action in the Pacific would consist of a defensive holding strategy until Hitler was defeated, there were a substantial number of men, ships, and planes in the Pacific Theater. The question was how to use them effectively and who should lead them.

There were two candidates, General Douglas MacArthur and Admiral Chester Nimitz. American naval staff, including Fleet Admiral William Leahy and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King, convincingly argued that the vast expanse of the Pacific dictated that the war would be primarily a naval one and should be led by an admiral rather than a general.

MacArthur Pressures For Command

However, MacArthur and his supporters were pressuring President Roosevelt to give him command of the entire Pacific Theater. MacArthur was the second highest ranking officer in the Army and was a controversial character—beloved by his men and hated by many who thought him to be pompous, egotistical, and vain. His larger than life persona coupled with his extreme seniority made it unlikely he would be subordinate to any naval commander. Also, viewed politically, the general’s considerable following posed a potential threat in future elections; perhaps MacArthur might even emerge as a presidential candidate to challenge Roosevelt himself.

Whether swayed by MacArthur’s considerable charm and persuasive power or concerned about a future rival, Roosevelt overrode his command staff and created a place for MacArthur. He carved the Pacific into two theaters with MacArthur named as Supreme Commander of the Southwest Pacific Area, which encompassed Australia, the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, the Netherlands East Indies, and the Philippines. The rest of the Pacific was assigned to Nimitz with the title Commander in Chief Pacific Ocean Areas. Furthermore, each theater was considered an independent command with neither the general nor the admiral answering to the other.

The Split Between MacArthur and Nimitz

This may have seemed like a good compromise at the time, but it violated a sacrosanct principle of war—unity of command. Nimitz’s immediate superior was the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest King, while MacArthur answered to Chief of Staff of the Army General George Marshall. Although King and Marshall deferred to a degree to Admiral William Leahy, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, it was Roosevelt who had the final word on matters concerning the conduct of the war. So the common commander in the Pacific was effectively the president himself.

Initially, this posed no major problem, but it would have severe consequences later because MacArthur and Nimitz had two different strategies for defeating Japan. Nimitz and the Joint Chiefs advocated island hopping across the central Pacific, skipping over the Philippines, and establishing an invasion base on the island of Formosa, now known as Taiwan. Their vision was clear: secure the Marshalls and the Solomons, thereby protecting the supply routes to Australia and New Zealand, then occupy the Marianas and Formosa. An advantage of this strategy was the early ability to secure an island air base within bomber range of Japan.

MacArthur’s proposed strategy was to slog through the coastal jungles of New Guinea, through the Philippines to southern China, and mount an invasion of the Japanese home islands from there. Of course, spending resources on this strategy could delay the occupation of Formosa and the bombing of Japan’s home islands.

Focus on the Philippines

MacArthur had a strong bias and an unrelenting focus toward the Philippines. He was military adviser to the Commonwealth government of the Philippines for four years beginning in 1937, and his father had been governor general in 1900. He was also a close friend of President Manuel Quezon, who in 1942 gave MacArthur $500,000 as payment for his prewar service. It was unprecedented for an activeduty Army officer to accept such a sum, equal to approximately $7.5 million today, from a foreign government. Although this gift was known to FDR and Secretary of War Henry Stimson, it did not become public for 34 years until historian Carol Petillo unearthed it while researching her doctoral thesis in 1979—15 years after MacArthur’s death.

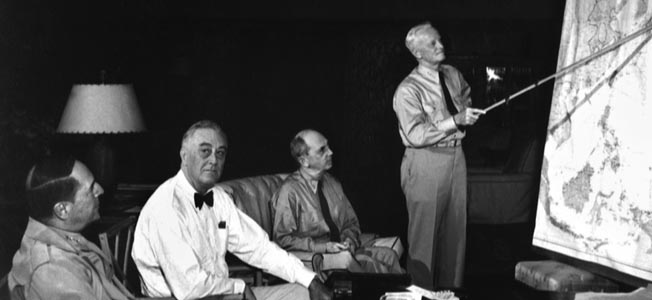

The strategic debate was not settled by the summer of 1944, when Roosevelt sailed to Honolulu to meet personally with the two men that he had charged with running the Pacific War. Opinions differ on the reason or even the necessity of this meeting. The stated official purpose for the meeting was for Roosevelt to resolve the differences between his commanders and decide where American forces should go next in the Pacific. Some believe that his real motivation was to be photographed with his theater commanders so that voters would see him as commander in chief, as potential rival MacArthur’s boss. It was, after all, an election year, and just the day before Roosevelt embarked on the heavy cruiser USS Baltimore for Honolulu he had been nominated for an unprecedented fourth term. This was an opportunity to show the nation that he possessed the stamina to remain commander in chief for another four years at a time when his health was increasingly under scrutiny. Within nine months he would be dead.

Determining the Future Course of War

Whatever his primary reason, FDR was about to arbitrate between his two commanders and determine the future course of the war and thousands of American lives. The decision would depend upon who would prove to be more convincing—MacArthur or Nimitz. Roosevelt considered himself something of a naval strategist because of his seven-year term as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, so he felt fully qualified to make this decision.

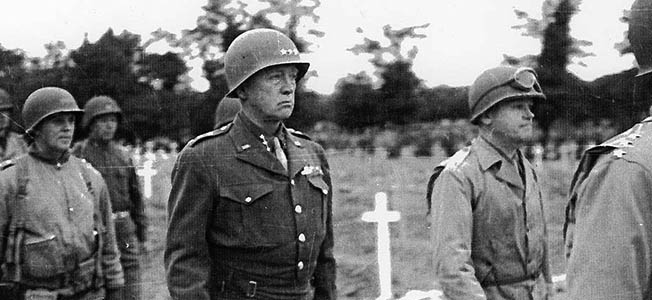

MacArthur was reluctant to leave his command and resented being forced to fly to Honolulu for what he called “a political picturetaking junket.” On July 26, his personal Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress named Bataan landed at Hickam Field an hour before the USS Baltimore docked, but MacArthur did not join Nimitz and the formal welcoming party at the pier. Rather, he went to the meeting in a long, openair limousine with an elaborate motorcycle escort and accepted the welcome of cheering crowds along the route.

The meeting was held at the luxurious Waikiki Beach mansion of Christian Holmes, owner of Hawaiian Tuna Packers and heir to the Fleischman Yeast fortune. Nimitz presented his carefully prepared case using charts and statistics to show the advantages of Formosa as a main base for the final operations against Japan. From a strategic point of view, a single force moving across the Central Pacific toward Japan made good military sense. However, it was an unacceptable political decision. If Nimitz was given all the resources from the Southwest Pacific Command in order to have overwhelming superiority for a single thrust across the Central Pacific, MacArthur would be placed in a minor role for the remainder of the war. This would not play well among MacArthur’s supporters and the American people. After all, shortly after fleeing Corregidor he was feted as a hero and was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Secret Agreements Between MacArthur and FDR?

MacArthur was at his best that evening. He had no notes, no prepared maps of his own, and absolute certainty that he was right. He argued that the United States had a moral obligation to liberate 17 million Filipinos before assaulting Japan. Bypassing most of the Philippines would, in his view, be militarily and politically disastrous and give truth to Japanese propaganda that we had abandoned the Filipinos and would not shed American blood to free them or any other nonwhite people. This would lead to a loss of prestige among all the peoples of the Far East and would adversely affect the United States for many years. He pointed out that the Chinese population on Formosa could not be counted on to support American forces and might, in fact, be openly hostile, whereas the Filipinos were totally loyal to the United States.

MacArthur had another reason to return to the Philippines. He was the Manila-based commander of U.S. Army forces in the Far East on December 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and despite being immediately notified of the attack and ordered by Marshall to execute existing war plans, he did nothing. Eight and a half hours after the Pearl Harbor attack began, Japan’s 11th Air Fleet achieved complete tactical surprise and destroyed 100 aircraft at Manila’s Clark field—virtually the entire Far East Air Force. Two weeks later, MacArthur moved his headquarters to Corregidor Island in Manila Bay, and in March 1942, he fled to Australia in an 80-foot PT boat on Roosevelt’s orders. Whether caused by his gratitude for the $500,000 gift or embarrassment for his ineptitude in Manila or guilt for abandoning his troops on Corregidor, he made a convincing case to liberate the Philippines.

By midnight, no decision had been made, and Roosevelt said that he would sleep on it. The next morning, FDR and MacArthur met privately. Some historians believe they reached a secret agreement whereby MacArthur would be allowed to recapture the Philippines but agreed to refrain from openly supporting New York Governor Thomas Dewey, Roosevelt’s likely presidential opponent in the coming fall election.

Roosevelt was well aware of MacArthur’s huge following in the United States. As early as April 1943, Michigan Senator Arthur Vandenberg, along with a group of high-profile conservative Republicans, started to organize a “MacArthur for President” movement. This group included John Hamilton, former chairman of the Republican National Committee, Roy Howard of the Scripps-Howard newspaper syndicate, and Colonel Robert McCormick, owner and publisher of the Chicago Tribune.

Although the leading Republican nominees for president were Dewey and Wendell Willkie, who had lost to Roosevelt in 1939, MacArthur was prominently mentioned. In fact, his name was entered in the Wisconsin presidential primary election where he came in third.

MacArthur Gets His Way

Later that day, Roosevelt insisted on making a motor tour of the Oahu military bases. Nimitz later wrote that in the course of the drive, in which the admiral and the general were sandwiched in the open limousine on either side of the president, he knew from the congenial conversation between the general and the president that MacArthur had won all his points.

However, it was not until Roosevelt returned to Washington, D.C., that his decision was made public in a radio broadcast when he simply announced complete accord with his “old friend” General MacArthur. Soon after that, the Joint Chiefs confirmed the two-pronged approach to Japan.

This decision cost tens of thousands of American lives. If the United States had not planned to invade the Philippines, the Allied military would have avoided the thousands of casualties suffered in New Guinea. Furthermore, the Allies would have avoided the pointless fight for Palau, particularly the island of Peleliu, which Nimitz believed necessary to support the Philippine landings and to protect MacArthur’s right flank. Lastly, the Allies would have saved the 10,380 Americans killed and the 36,631 wounded during the liberation of the Philippines.

While the fateful meeting was happening in Honolulu, 3,700 miles to the west the Pacific Island Invasion Force, which left Hawaii the week before the invasion of France, was fighting a bloody battle to occupy Saipan in the Mariana Islands. In fact, this resulted in the highest casualty toll to date in the Pacific with 3,000 American dead and 10,000 wounded. The Japanese suffered 30,000 dead along with 22,000 civilians, many of whom committed suicide. Their calamitous defeat offered proof to Japanese leaders that military victory was not attainable. Nine days after Saipan was secure on July 9, 1944, Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo and his entire cabinet resigned. Four years later, Tojo was executed as a war criminal.

The occupation of the Marianas, including the islands of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian, was important because it could accelerate the bombing of Japan. When the Formosa strategy was developed, two types of bombers with enough range to travel the 1,000 miles from Japan to Formosa were available: the B-17 Flying Fortress and the Consolidated B-24 Liberator.

Several Mysteries Remain

This was soon to change when the Army Air Forces concluded a competition for a longrange bomber in May 1940. The Boeing B-29 Superfortress had a speed of 350 miles per hour, a bomb load of 10,000 pounds, twice that of the B-17, and a range of 3,500 nautical miles, more than enough to reach Japan from the Marianas and return. The B-29 was a highly advanced design with many innovations, including a pressurized cabin and revolutionary central weapons control system that operated four machine-gun turrets remotely. Because of this complexity, coupled with unreliable engines, delivery did not begin in quantity until early 1944. However, by the time Tinian was occupied on August 1, 1944, B-29s had been flying from India and forward bases in China for several months.

The U.S. Joint Chiefs selected Tinian as an operational base because it had two existing airfields, West Field in the center of the island and Ushi Point or North Field. As soon as Tinian was under American control, Navy Seabees began a massive construction project at North Field to repair and expand the existing runway and build three additional two-mile-long runways. This was one of the largest construction projects of World War II, with more than a million cubic yards of earth and coral moved. By early 1945, North Field had become the largest and busiest airport in the world, home for 1,000 B-29s that took off and landed every minute around the clock to bomb Japan.

On August 6, Colonel Paul Tibbets left Tinian and piloted the B-29 Enola Gay to Hiroshima and dropped Little Boy, a 16-kiloton uranium bomb. Three days later, Major Charles Sweeny in the B-29 named Bock’s Car released Fat Man, a plutonium bomb of even more destructive power, on Nagasaki. On August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito announced in a radio broadcast to his people that Japan had surrendered and the war was over. The United States never did utilize the Philippines to bomb Japan or stage an invasion of the home islands, and it is doubtful that their liberation helped to end the war.

The Pacific War was widely reported in the press, in photographs, and in newsreels, but several mysteries remain. Why did MacArthur ignore warnings about a possible Japanese attack on Manila on December 7, 1941? Why was he so intent on liberating the Philippines? Why did FDR consent to MacArthur’s strategy against the advice of his general staff and military advisers? Why did Japan continue to fight after its navy was destroyed, its oil sources were cut off, and it was clear by any objective analysis that victory was impossible?

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments