By Eric Niderost

On a December day in 1793, Maj. Gen. Anthony Wayne led a column of soldiers to a spot deep in the Ohio wilderness not far from the Wabash River. This forlorn patch of woods was the site of St. Clair’s defeat, where over 600 U.S. soldiers lost their lives to hostile Indians. Some two years earlier, on November 4, 1791, the major general and governor of the Northwest Territories, Arthur St. Clair, had blundered into a trap. When surrounded and attacked by a thousand warriors, his ill-trained rabble of an army disintegrated into a panicking, fear-stricken mob. Benumbed by terror, the Americans fell easy prey to showers of Indian arrows and musket lead. General St. Clair ordered a retreat, which quickly became a rout. Somehow St. Clair and what remained of his men managed to cut their way out of the trap, blindly racing through the forest for the safety of Fort Jefferson, 29 miles away. Everything had been left behind, including eight cannon and supplies. The wounded were also abandoned, left to await their inevitable deaths by tomahawk or scalping knife.

St. Clair’s battle was destined to become the worst defeat ever sustained by the U.S. Army in the Indian Wars. The bungling general sustained 900 casualties, including 527 dead and 263 wounded. But the greatest casualty was national honor. Could it be redeemed?

Now, two years later, American soldiers were back, gazing with horrified eyes at the utter devastation they saw all about them. Battle debris was everywhere; moldering bits of uniform, mildewed cartridge boxes, and broken bayonets lay scattered about. But it was the thousands of bones that made these forested glades an open-air sepulcher. Wolves and other predators had scattered the skeletal remains far and wide. Skulls looked up into the trees with sightless eyes, the battered craniums showing not only fang punctures but also the telltale marks of Indian scalping.

Around 600 skulls and other bones were reverently gathered and buried in a mass grave and given full military honors. Some friendly Delaware Indian scouts had located four of St. Clair’s abandoned cannon, which were then fired off in salute. General Wayne observed the proceedings intently, making sure all was correct, then gave orders for a fort to be erected on the site. Soldiers went to work with a will, and soon the forest rang with the sounds of chopping axes and the creaking groan of felled trees as they crashed to the forest floor. In token of its great symbolic, as well as military, significance, the new post was dubbed “Fort Recovery.”

The struggle for the Northwest had its roots in the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolution. The United States was now an independent nation with boundaries that stretched to the Mississippi River. The fledgling country was saddled with war debts, and Congress wrestled with various expedients to solve the problem. The struggling new republic was cash poor, but also land rich. Attention focused on the Old Northwest, a vast tract of some 248,000 square miles of virgin wilderness north of the Ohio River. If those lands could be sold to pioneers, America’s debt troubles would be considerably eased.

Congress lost no time in passing the Land Ordinance of 1785, which provided for the sale of wilderness lands in 640-acre tracts. The average price would be only about a dollar an acre, but few Americans could afford $640. Speculators, many of them Revolutionary War veterans, pooled their resources and formed land companies to gobble up large tracts of virgin wilderness. The idea was to resell these tracts to small farmers, thereby recouping their initial investment and making a tidy profit in the bargain.

The Ohio Company managed to obtain 1.5 million acres of wilderness to develop, the Scioto Company five million acres, and soon the printing presses were busy churning out promotional pamphlets extolling the virtues of the new lands. Some of the literature indulged in sheer flights of fantasy, but the reality was fabulous enough. There were vast forests, swift-flowing streams, and abundant wildlife. Above all there was the soil—thick, black humus that was fertile and yards deep.

These developments sharpened an already ravenous hunger for new lands. The Ohio Company lost no time in developing its claims, and in April 1788 the town of Marietta was founded on the east bank of the Okasis River, not far from where it joins the winding Ohio. Soon as many as 10,000 settlers a year were streaming into the wilderness.

There were others who viewed these events with alarm. The Northwest Territories were home to many Indian tribes, some of them displaced from areas farther east. There were the Ottawa, Ojibway, Wyandot, Delaware, and survivors from the shattered Iroquois Confederacy. In addition to these refugees were tribes who were native to the upper Midwest and Great Lakes region. These included the Shawnee, Miami, Weas, Piankashaws, Potawatomi, Illinois, Fox, and Winnebago, to name a few.

Even while claiming ultimate jurisdiction, Congress made treaties with individual tribes in an effort to have the natives sell or cede land as white immigration pressure increased. The government reasoned that the Indians, being “savages” as well as “nomadic hunters,” would willingly retreat before the advance of civilization. It was a naive assumption.

The Northwest tribes had no intention of fading away or giving up ancestral lands without a fight. Michikinikwa, known to the whites as Little Turtle, was a Miami chief who had the ability and charisma to unite the tribes against a common enemy. He was a big man, said to be six feet tall, and his partly shaved forehead was more than compensated for by the long, raven strands that fell down his back. He was ably seconded by the Shawnee leader Weyapiersenwah, or Blue Jacket.

But there was another Shawnee present who was rapidly gaining a reputation for bravery in battle and also a kind of maturity and wisdom well beyond his 26 years. His formal name was nila ni tekamthi manetuwi msi-pessi, or “Crouching Panther, Blessed with the Magical Powers of the Shooting Star,” according to one recent translation. Most Shawnee who knew him simply called him Tekamthi. In years to come, even his white enemies would respect him as the great war chief Tecumseh.

Indian warfare was cruel, but tribes felt they were only defending their homes and families from the rapacious American shemanese, “long knives.” “The Americans,” a native delegation once complained in 1784, “put us out of our lands, extending themselves like a plague of locusts.” The natives were fighting not only for their homes but also their culture, traditions, and way of life.

These Native Americans were strongly supported by the British, who maintained a series of Northwestern forts on U.S. soil in direct violation of the 1783 Treaty of Paris. On paper the forts were there to “punish” the Americans for their own treaty violations. The United States had solemnly pledged to compensate exiled American loyalists—the hated “tories”—for property losses they had sustained. The 1783 treaty also stipulated that Americans pay off pre-Revolutionary debts owed to British merchants, a clause conveniently forgotten once independence was fully achieved.

Although there was some truth to the allegation that the forts were there to force the Americans to honor treaty obligations, in some ways it was a diplomatic smokescreen that Britain maintain its posts on American soil to protect Canada and maintain its lucrative fur trade with the tribes of the Great Lakes and beyond. In the 1780s there was always the hope that, as seemed likely at the time, a weak and squabbling United States would fall apart. If that ever happened, the Old Northwest would fall into British laps like ripe fruit.

In the meantime, Miami Confederation war parties did what they could to disrupt American plans to open up the country for settlement. They were aided and abetted by the British, who encouraged the effort and kept the tribes well supplied.

American farms were raided, their inhabitants cut down and scalped without mercy. Flatboats and other river craft were attacked all along the broad Ohio, and attacks were launched into Kentucky.

The Kentucky raids were particularly bloody, products of a war of mutual extermination that had been going on since the 1770s. The flood of new settlers was reduced to a trickle as word of Indian massacre and atrocities, magnified many times as the lurid stories passed from one to another by word of mouth, spread throughout the land.

Between December 1784 and August 1789, the minuscule U.S. Army built or repaired a chain of nine forts along the Wabash and Ohio River valleys. The army wasn’t just small, it was skeletal, never numbering more than around 500 or 600 effectives at any given time.

Under the circumstances, recruiters had to make do with what they could find. The men who enlisted had a wide variety of reasons for risking their lives on the fringe of civilization. Some were criminals escaping justice, while others were drifters and tramps, gutter sweepings of Boston and other towns. There were also a large number of Irish immigrants, happy to escape the poverty and political oppression of the Emerald Isle, and a few country boys, chasing fantasies of adventure that were preferable to the realities of farm life.

In 1789 President George Washington came into office as chief executive of a new and stronger constitutional government. Washington opened negotiations with the Creek tribe, but Miami Confederation attacks continued unabated. In some cases the Indians were merely responding in kind, having themselves been wantonly attacked by white settlers. There seemed to be no end to the spiral of violence; white cruelties were answered by Indian atrocities.

Washington was determined to pacify the frontier, and so orders were issued to Brig. Gen. Josiah Harmar to lead an expedition against the hostile Indians. In September 1790, Harmar managed to assemble 353 regulars and 1,133 militia for the task at hand. This punitive expedition located some abandoned Indian towns along the Maumee River and put them to the torch. Harmar then foolishly sent out unsupported detachments in an effort to find the elusive natives. The Indians were swift to retaliate, falling on the floundering American detachments and inflicting around two hundred casualties.

Harmar’s raw militia were so unnerved by these events that they were finished as an effective fighting force. There was nothing Harmar could do but retreat to Fort Washington, present-day Cincinnati. The president decided to try again, this time with General Arthur St. Clair in command. St. Clair was one of the original investors in the Ohio Company, and was currently serving as governor of the Northwest Territories. As we have seen, St. Clair fared no better than did his predecessor.

President Washington heard the news of St. Clair’s disaster when Secretary of War Henry Knox managed to discreetly inform him of it during a dinner party. The president’s calm, collected, and dignified façade hid a volcanic temper—a temper that boiled to the surface after the last guest departed. “Oh God! Oh God,” Washington raged, “he [St. Clair] is worse than a murderer! To suffer that army to be cut to pieces, hacked, butchered, tomahawked by a surprise—the very thing I guarded him against!… How can he answer to his country? The blood of the slain is upon him!”

After the recriminations came sobering reflections. It wasn’t merely America’s prestige that was at stake, but also her very future. If the Indian threat was not eliminated, the United States would never reach its potential. It would forever be a backwater, an outpost of Western civilization clinging to the Eastern fringe of a vast and untapped continent. Washington had to pick a new commander for the army, a decision that was perhaps the most crucial of his presidency.

Washington was a methodical man whose patient deliberations were the despair of others, but once he made a decision nothing could shake his resolve. He understood that St. Clair had been his choice, so he shared something of the responsibility for the debacle. This time, there was no room for error. Some Virginians were lobbying for Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, future father of Robert E. Lee, but Washington was unimpressed. No, the more he thought about it, the more he felt Anthony Wayne was the man for the job.

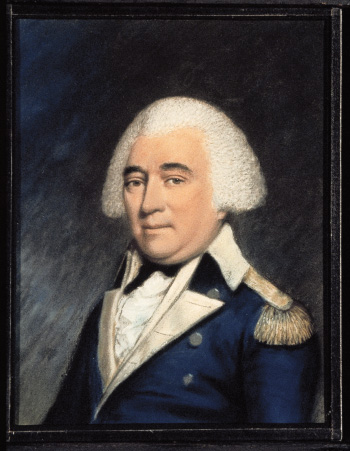

There were many who thought it an odd choice. True, Wayne had distinguished himself during the Revolution, particularly with his capture of a British post at Stoney Point in 1779. He was brave as a lion and capable of independent command. Everyone agreed he was a good Revolutionary officer—but that was nine years earlier, and a lot of water had gone under the bridge. The Anthony Wayne of 1792 was a middle-aged man plagued with bad luck and debts. At 47, his expanding waistline and troublesome gout bore mute testimony to his love of high living.

Many felt he was too open to flattery, and Washington himself admitted he felt Wayne “more active and enterprising than judicious and cautious.” But all in all, the president felt he was the man for the job.

Shocked by St. Clair’s terrible defeat, Congress moved with uncustomary swiftness and resolution. On March 5, 1792, Congress passed an act for “the protection of the Frontiers of the United States.” The U.S. Army would undergo a thorough reorganization, a revamping that would change the institution from top to bottom. The old regimental system would be scrapped, and in the process a new fighting force would emerge from the ashes of the old. The new law created the Legion of the United States, 5,120 soldiers divided into four separate units known as Sub-Legions. On paper, each Sub-Legion was to have 1,280 officers and men, and consist of eight companies of infantry, two companies of riflemen, an artillery company armed with four 6-pounder cannon, and a company of dragoons.

Following up on congressional actions, Washington appointed Anthony Wayne as commander of the Legion of the United States with the rank of major general. Wayne wasn’t eager for the assignment; his gout was troubling him, and he preferred a good table and a warm fire to the rigors of active campaign. In the end, he accepted the command. Wayne was never one to shirk responsibilities, and the appointment was a lifeline to a man drowning in debt.

In the spring of 1792 Maj. Gen. Wayne climbed into his carriage to begin his journey to Pittsburg (now Pittsburgh), Penn. American roads ranged in quality from barely tolerable to utterly wretched; some were little more than rutted tracks choked with dust in summer and muddy quagmires in winter. His trip must have been bone jarring but leisurely, because the Legion of the United States existed largely on paper. There was no army worthy of the name—only a few of St. Clair’s thoroughly cowed survivors huddling behind the wooden palisades of Forts Jefferson, Hamilton, and Washington.

It would take time for supplies to be gathered, arms stockpiled, and men recruited and trained. Wayne knew that most of the army’s troubles stemmed from an overreliance on raw militia. They lacked the steadiness and dependability of trained soldiers. Sometimes, they could fight well, but they were prone to panic and all too often took to their heels. During one of the Harmar skirmishes, 75 regulars had fought to the last man, while their 108 militia comrades fled the field.

Wayne knew he needed a trained army if he had any hope of winning a decisive victory, and this took time. The general was in no particular hurry to take the field; in fact, he petitioned Washington and Secretary of War Knox to postpone an offensive until 1793. Above all, Wayne did not want to conduct a winter campaign when the logistics and weather would favor the Indians. Washington granted Wayne’s request for a delay, using the time to launch some diplomatic initiatives aiming to reach a peaceful solution to the problem.

As the months wore on the Legion of the United States took definite shape. Wayne accepted most of the organizational reforms, but added a few twists of his own. He corresponded frequently with Secretary Knox, sweating couriers galloping back and forth between the nation’s capital at Philadelphia and Wayne’s headquarters at Fort Lafayette in Pittsburg. On July 27, 1792, Knox ordered Wayne to provide “distinctive marks” on the hats of each Sub-Legion. Each Sub-Legion was to have a distinctive unit color to smarten its appearance and foster esprit de corps. The 1st Sub-Legion would have white, the 2nd red, the 3rd yellow, and the 4th green.

Wayne admonished his recruiters to enlist only “brave, robust, and faithful” soldiers, but pickings were decidedly slim. A year before St. Clair’s army had been described as the “off scourings of large towns and cities, enervated by idleness, debaucheries, and every species of vice.…” The bedraggled specimens that now skulked into Fort Lafayette were from the same mold.

Wayne was not discouraged because he knew that with proper training and leadership, stiffened with rigid discipline, even such unpromising material could be transformed into good soldiers. But he had to get his men away from Pittsburg, a bawdy, vice-ridden river town where shabby taverns sold cheap liquor and prostitutes plied their trade.

The general decided to move the army 20 miles downriver to a new winter quarters camp called Legionville. Legionville, located in what is now Beaver County in western Pennsylvania, is celebrated as the true birthplace of the U.S. Army that had emerged in the wake of the Revolution.

Many of the men who served at Legionville would later leave an indelible mark on American history. Lieutenant William Henry Harrison was only 19 years old when he arrived in camp, but Wayne was so impressed by the young man he made him an aide-de-camp. Harrison would later become a distinguished general and seventh president of the United States. William Clark was a 22-year-old officer with a shock of reddish hair and an easy-going manner. He would achieve fame as an explorer a decade later on an expedition with Meriwether Lewis. Zebulon Pike was even younger when he joined the Legion, only about 15. He, too, would make his mark as a trailblazer, giving his name to the majestic Colorado crag known as Pike’s Peak.

The long, dreary months of winter finally passed, and the men welcomed the signs of spring. On April 25, 1793, the army left Legionville and proceeded in boats down the Ohio River to Fort Washington. Fort Washington was a sturdy post that featured walls two stories tall and thick blockhouses at each corner. General Wayne decided to set up camp beyond the walls of the fort at a place he called Hobson’s Choice.

In September 1793, Wayne and the main body of some 3,000 Legionaire regulars marched north, accompanied by 700 Kentucky mounted volunteers. Forts Hamilton, Jefferson, and Recovery were reprovisioned and reinforced, but Wayne wasn’t done yet. About five miles north of Fort Jefferson, he built a new post that he dubbed Fort Greeneville in honor of his old Revolutionary War comrade, Nathaniel Greene.

Fort Greeneville was a large cantonment, encompassing 50 acres of land and boasting a stockade that reached 10 feet high. This was to be Wayne’s winter quarters and a forward staging area for next year’s all-but-inevitable offensive.

As the Legion proceeded northward the Indians began to ambush isolated patrols and attack wagon supply columns. A Lieutenant Lowery was leading a supply convoy of 25 wagons when he was suddenly hit by a war party five miles from Fort St. Clair. Lowery was killed, along with 13 men of his command, the Indians plundering some of the wagons and running off 62 of the draft horses.

In another incident, young Cornet William K. Blue was guarding a grazing horse herd with 30 men. Indians suddenly appeared nearby, so the young officer drew his saber and ordered a charge. It was a trap. Four hidden Indians rose up and peppered the horsemen with lead, killing two sergeants. When the young officer looked around, he saw to his chagrin that the rest of his command had dug into their horses’ flanks and fled.

This was a serious breech of discipline; if left unchecked, fear might infect the whole army, undoing the patient training of the preceding months. The men who had deserted their officer in the face of the enemy were court-martialed. As an example, the man who led the retreat was singled out for special attention and ordered to be shot. After the death sentence was handed down, Wayne ordered the man’s grave dug. The entire army was drawn up to watch the execution, but Wayne delayed the proceedings to harangue the chastened troops. At the very last moment the man and his companions were pardoned, but the general had made his point.

After establishing Fort Recovery, Wayne and his officers went back to Fort Greeneville and winter quarters. On January 1, 1794, Wayne and his staff greeted the new year with a sumptuous repast that included roast venison, roast beef, roast mutton, veal, turkey, sweetmeats, ice cream, and plum pudding, all washed down with copious amounts of wine.

General Wayne’s slow but steady advance into the heart of Indian country was closely scrutinized by native leaders. The Miami Confederation, once buoyed by a string of victories, was now showing signs of weakening. Tiny cracks of disagreement threatened to widen into yawning chasms of disunity, shattering the hard-won alliance forever. To strengthen Indian resolve the British built Fort Miamis on the banks of the Maumee River, a strongpost with four bastions, a 25-foot trench lined with a prickly row of stakes, and 14 cannon. Located about 55 miles south of Detroit, it also guarded the approach of that all-important British trading stronghold.

Eventually various Indian tribes agreed to attack Fort Recovery, which was believed to be bulging with supplies for the upcoming American offensive. Great Lakes tribes—among them the Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi—joined forces with warriors from the Ohio Country—Shawnee, Miami, Delaware, and Wyandot. Scouts reported a large pack train of horses bearing loads of flour had just arrived at Recovery. Blue Jacket argued that the Indians should pounce on the vulnerable pack train when it emerged from the fort to begin its return journey. The Lakes tribes disagreed, feeling the fort itself was a far more important prize. When Blue Jacket reminded them Recovery was strong and could not be taken without cannon, the Great Lakes Indians scorned what they saw as weakness.

After some last-minute wrangling, Blue Jacket’s plan was adopted—or so it seemed. Early in the morning of June 30, 1794, Major William McMahon’s pack train left Fort Recovery with an escort of 90 riflemen and 50 mounted dragoons. It was around 7 am, but the rising sun beat down with a fierce glare, and as temperatures warmed, sweat began to trickle down foreheads and stain woolen-coated armpits.

The Indians were waiting just down the trail, a huge force of between 1,500 and 2,000 warriors stiffened by—if the stories are true—Canadian militia and a few Redcoats. The trap was sprung not far from Fort Recovery, taking the pack train by complete surprise. Men crumpled onto the forest trail, felled by a storm of musket lead, and wild-eyed horses plunged and reared in a vain effort to escape the carnage, nostrils distended in fear. Major McMahon was a big man, about six-feet-four in height, but somehow the whistling balls managed to miss his blue-coated, red-haired bulk. His voice bellowing over the cacophony of battle, he ordered a fallback to the fort.

Hearing the commotion, some dragoons from the fort galloped out to the rescue. The troopers ran headlong into the survivors of the stricken supply train, a human tide of bodies so packed the dragoons had trouble making headway against the current of flesh. Indian warriors fired from behind underbrush and trees, barely seen save for the telltale gouts of white smoke and flame that spurted from their muskets. Native muskets emptied many saddles, forcing the others to join the pack train exodus.

The Fort Recovery battle was shaping up into a real disaster for the Americans. Many cattle and packhorses had been taken, and 50 Legionaries killed or wounded. Captain Alexander Gibson decided to lead an infantry sortie from the fort, a split-second decision that tipped the scales against the Indians.

Captain Gibson drew his sword and led his men out of the gates with their bayonets fixed. The infantry company rushed forward, engaging the enemy with such vigor the surprised warriors were forced to give way. But Gibson’s momentary absence seemed to present a new opportunity to the Great Lakes warriors who had not yet joined the pack train fight. The gates were open—an invitation to rush in and seize the post.

The temptation proved too great, and a mass of warriors emerged from the woods, making for the beckoning gates as fast as their legs could carry them. Howling triumphantly, paint-daubed warriors funneled into the gate—and were met by a withering musket volley and a shattering blast of grapeshot. The grapeshot did great execution, cutting a bloody swath of destruction.

At least 40 or 50 warriors were killed or wounded in the gate rush, and possibly more. The dazed survivors scattered into the woods. The Great Lakes warriors had little sympathy from Blue Jacket, who had triumphantly returned with many scalps and packhorses. Watered by defeat, the seeds of discord now germinated and flowered, until the Ohio Confederacy teetered on the brink of collapse.

The fragile tribal alliance was further weakened by the announcement that Little Turtle would not lead the Indians when Wayne finally made his move. Little Turtle had begun to realize the ultimate futility of their resistance, especially when faced with an enemy the caliber of Anthony Wayne. Indians might win victories, but the Americans never seemed to accept defeat. They always somehow managed to raise another army, and another. When Little Turtle counseled peace, Blue Jacket scornfully denounced him to his face as a coward.

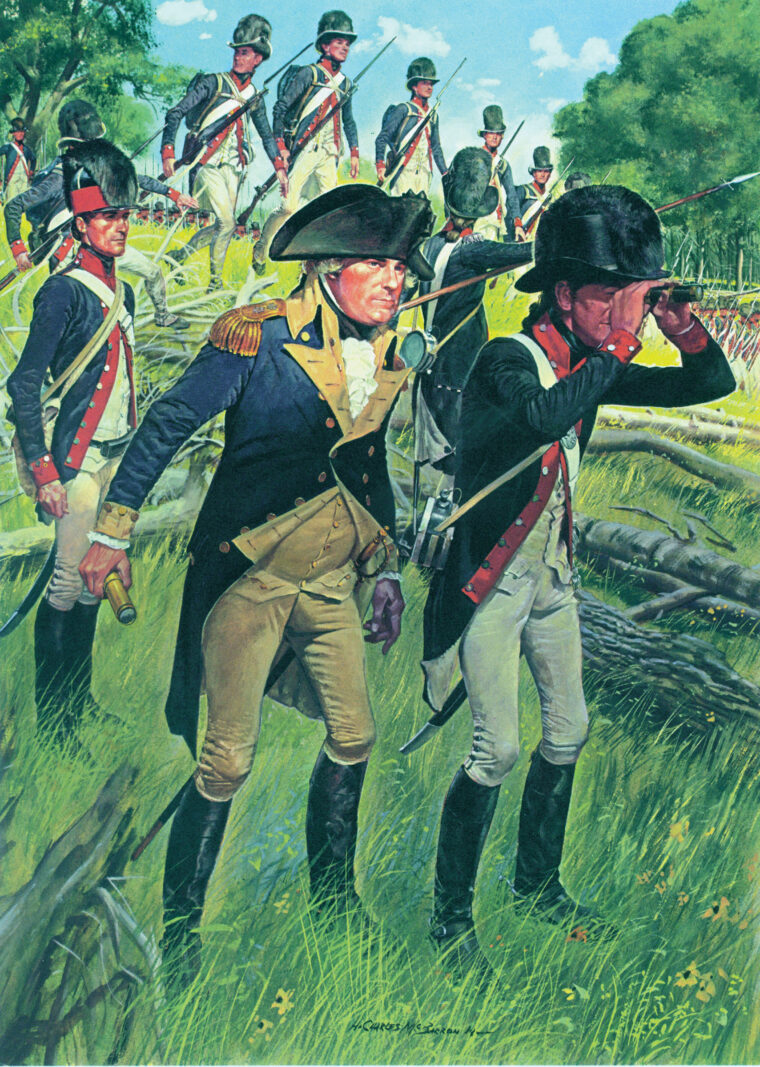

Buoyed by the Indian repulse at Fort Recovery, Wayne ordered the Legion to begin its long-awaited offensive. The army left Fort Greeneville on July 28, 1794, a force that consisted of about 2,000 Legionaries and 1,500 Kentucky militia. The following day they reached Fort Recovery and continued their steady advance north. Chief Scout William Wells—called “Captain of the Spies” by General Wayne—was well in front, probing the woods for any sign of enemy activity.

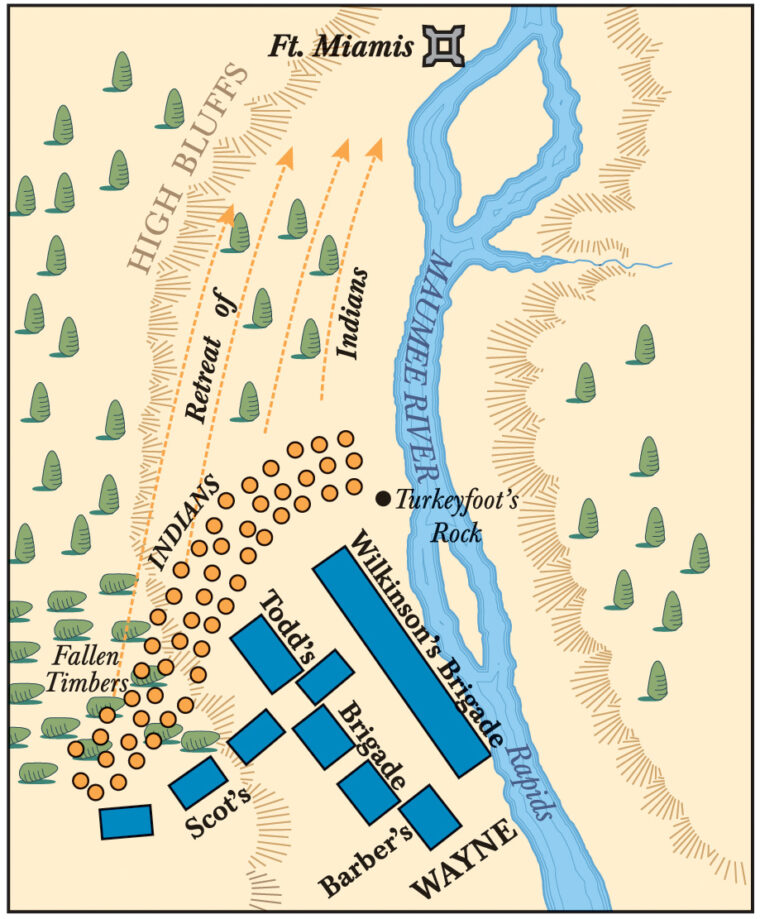

On the morning of August 20, 1794, Wayne’s army was nearing the approaches of Fort Miamis, the Maumee River on their right flank. The once-powerful Miami Confederation was now weakened by many defections. Many discouraged warriors simply went home in disgust, while others left to find food. It was the Indian custom to fast before battle and, if certain reports are true, some warriors believed Wayne was going to attack sooner than he actually did. When the Legion failed to show up, they left in search of game.

Blue Jacket’s host now numbered around a thousand, including some 150 Canadian militiamen disguised as natives. Because the Maumee River anchored the approaching Wayne’s right flank, Blue Jacket hoped to swing around and attack on the left, hiding his painted warriors in a tangled mass of hardwood trees that spiked the sky. If the plan bore fruit, the Legion might even be trapped with its back against the Maumee.

The Indian positions stretched from Blue Jacket’s thick woods to the river that snaked its way through a broad meadow. The native line was thinly held, but some natural features aided in the defense. The whole area was a labyrinth of downed sycamore and white oak trees, felled by the raging winds of a recent tornado. The battered trunks lay thick upon the ground, shattered stumps marking where they had once stood. This jumble of tree trunks, branches, and undergrowth made a natural wall that remedied, at least in part, the Indians’ lack of numbers. Because of the stricken trees, the area came to be known as Fallen Timbers.

It had been raining, but a bright sun that rose above the ragged treetops hinted of the torrid summer day to come. The Legion roused itself, hoping that sodden wool uniforms might dry quickly in the August heat. Wayne was up early, making sure that his hair was properly combed and whitened with powder, a custom that still prevailed among gentlemen of Wayne’s generation. The general was in a bellicose mood, made even sharper by the throbbing pulses of pain that coursed through his left leg, telltale symptoms of his old enemy, the gout. Wayne bandaged the stricken limb with red flannel, then set about taking care of some routine paperwork.

In the meantime the Legion’s advance guard was approaching Fallen Timbers. This was Major William Price and his mounted battalion of Kentucky Volunteers plus two companies of the Fourth Sub-Legion. The main body of the Legion marched a short distance behind them, two rows of blue-clad troops in trail arms order—in trail arms, the soldier gripped his musket with one hand, the gun butt trailing to the ground. This was easier than the by-the-book, shoulder-arm march, which didn’t account for the low-lying tree branches and heavy underbrush that plucked at soldiers’ elbows.

Suddenly a burst of Indian musket fire sounded out, disturbing the deceptively idyllic quiet of the forest glades. The mounted volunteers were momentarily surprised by the attack, and quickly wilted under the bullet storm. Captain Bartholomew Schaumburg galloped back to Wayne with the news they had been attacked. The impending battle was like a tonic to Wayne, the echoing sounds of musketry easing his pains more than any bolt of red flannel. He mounted his black horse with some difficulty, but galloped forward as fast as his mount could take him.

Once on the scene Wayne assessed the situation with a veteran’s eye. The Legion Infantry would go forward in two lines at a rapid pace, their trail-arms, gun-toting posture retained to help maintain their momentum. As they closed, muskets would swing forward in an all-out bayonet charge, the general having great confidence in the

winning qualities of cold steel. If and when the natives broke, advancing legionaries would fire a volley or two to complete the rout. The Indian right—the dark and shadowy belt of woods that harbored Blue Jacket’s warriors—didn’t look too promising for a flank attack, but it was worth a try, so Wayne assigned elements of the Kentucky Mounted Volunteers and other militia units to see what they could do.

Wayne pinned his hopes on the Indian left, near the river, where the open meadows that fringed the meandering stream made them seem more ideal for cavalry. Captain Robert Mis Campbell and the Legion Dragoons were ordered to attack this promising left. Much depended on timing, but if all went well Wayne might pull off a classic double envelopment, much like Hannibal did at Cannae against the Romans.

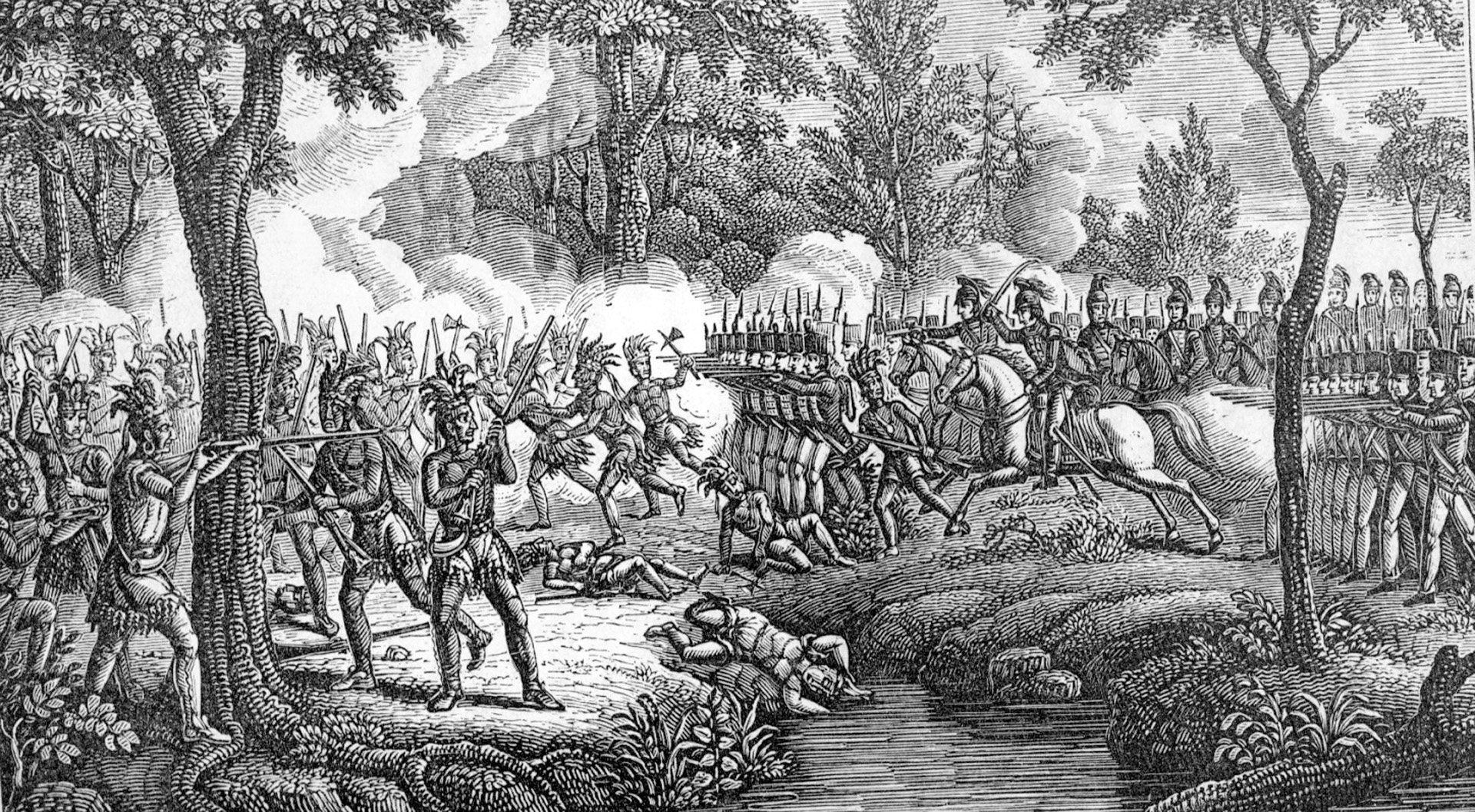

In the meantime the superbly trained Legion Infantry went forward at a run, trail arms at first, then a full bayonet charge as they neared the timber-cluttered barricades. Blood-curdling war-whoops rang through the trees, punctuated by deafening blasts of musketry. The sweating infantry could see the tangle of trees just ahead, and occasional glimpses of warriors from behind logs or through the smoky skein of powder smoke.

Musket barrels would appear from bushes or fallen tree limbs, then spout tongues of flame and clouds of dirty white smoke as they discharged.

Occasionally an infantryman would tumble into the forest detritus, his blue and buff uniform now bright with a spreading stain of crimson, but others pressed forward, the bearskin crests that decorated each Legionary’s hat glistening in the summer sun, and bayonet tips sparkling as they caught its rays. Once the Legionnaires reached the timber barricades, they engaged the warriors hand to hand. Knife- and hatchet-wielding Indians fought bravely, but were soon impaled on the lethal steel shafts.

The Indians began to break and run, unable to withstand the furious blue wave. As the warriors fell back in disorder, legionaries paused momentarily to fire a volley or two, then continued the advance. Such diligence had to be rewarded, so a ration of a half-gill (two ounces) of whiskey was distributed to the men. It was a thoughtful gesture, but Lieutenant Clark felt “much requited” because of the terrible exertions of the day.

The sudden collapse of the Indian center did not permit the classic “pincer” envelopment that Wayne had hoped for. Captain Campbell’s Dragoons found the meadows near the river less than ideal for cavalry envelopment. In fact, on closer inspection there were quite a few fallen trees scattered about, though perhaps not as thickly as farther from the river.

Captain Campbell ordered a charge, each man’s heavy saber rasping from the scabbards as they prepared to obey his orders. Digging their spurs into their horses’ flanks, they bolted forward at a gallop. Concealed warriors shot many dragoons from the saddle, but the others managed to clear the log barricades with the ease and efficiency of veteran fox hunters. Once past the timber barricades the rampaging horsemen committed terrible executions. Arcing sabers bit into necks, skulls, and shoulders, until the vermilion-daubed faces of Indian warriors became painted with red streaks of their own blood.

General James Wilkinson, Wayne’s second in command, was an inveterate schemer whose talents were more suited to political machination than battlefield maneuvers. Thoroughly conventional and completely confused, he kept on riding back to Wayne and hounded the preoccupied commander in chief with inane questions. “Be so kind,” Wayne finally snapped, “as to believe that I know what I am doing—see that you do too!”

Wayne did indeed know what he was doing—and so did his regulars. Hundreds of routed Indians started to stream to the imagined safety of Fort Miamis, about two miles north of the battlefield. Surely their British allies would not desert them. After all, it was the British who had encouraged them to resist American encroachments. When the warriors reached the fort they found the gates closed and barred to them. Three companies of British regulars were at Miamis, about 145 men, commanded by a Major William Campbell.

Indian refugees pleaded to the red-coated British sentries that patrolled the ramparts, but their entreaties fell on deaf ears. The Indians became angry, and it is said some English-speaking warriors let out a barrage of well-chosen four-letter oaths, but even curses would not move the Redcoats. The Indians had to fade into the woods to avoid American capture.

The battle had ended in complete American victory, a triumph for Wayne and his training methods. The Americans lost 31 killed and 102 wounded. Indian losses are calculated at about 40, but the native habit of carrying off their dead complicates these estimates. Their losses were probably much higher. Riding through the battlefield, Wayne was astonished to see that many warriors were completely naked. It was an Indian custom to wear only moccasins and a breechcloth in battle, but evidently many of the Indian corpses had lost their clothing, or perhaps had been stripped by souvenir-seeking soldiers.

A triumphant General Wayne compelled the Indians to sign the Treaty of Greeneville on August 3, 1795. Defeated in battle and once again abandoned by their British “allies,” the tribes had little choice but to agree to the pact. The tribes ceded a huge tract of land to the United States, an area that encompassed all of present-day Ohio and a portion of Indiana. Ironically, Little Turtle, the victor of St. Clair’s defeat, added his name to those of the signers.

Half-forgotten today, the Battle of Fallen Timbers ranks as one of the most important victories in American history. American title to the Northwest Territories had been granted on paper in 1783, but for many years thereafter it was little more than legal fiction. After Fallen Timbers, it was a fact. Without firm title to the Northwest, the growth of the United States across the American continent would have been impeded, if not stopped altogether.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments