By Michael E. Haskew

Italy was unforgiving. German resistance to Allied operations had been brutal since the Salerno landings in the autumn of 1943, and by the following spring frustration had mounted upon frustration.

The Allied VI Corps remained bottled up at the Anzio beachhead. Elsewhere, repeated pounding at the Winter Line, a formidable series of German fortifications that, along with the Bernhard and Hitler Lines, were collectively known as the Gustav Line, had brought high casualties with no headway against the strong enemy positions at Cassino. Two regiments of the 36th Infantry Division had been cut to pieces trying to cross the Rapido River. And perhaps worst of all, time was running out for the Mediterranean Theater in terms of priorities. The invasion of Normandy was coming, and once it occurred the Italian campaign would devolve into a sideshow—no less deadly than the fighting in Western Europe, but still a sideshow. Replacement troops and supplies would be scarce.

By the spring of 1944, it was time for an all-out, concerted effort to break the stalemate at Anzio, crack the Winter Line, and capture Rome, the Eternal City and the first Axis capital within the reach, if not yet the grasp, of Allied forces. British General Harold Alexander, commander of the 15th Army Group and later all Allied armies in Italy, put forth his plan to do just that.

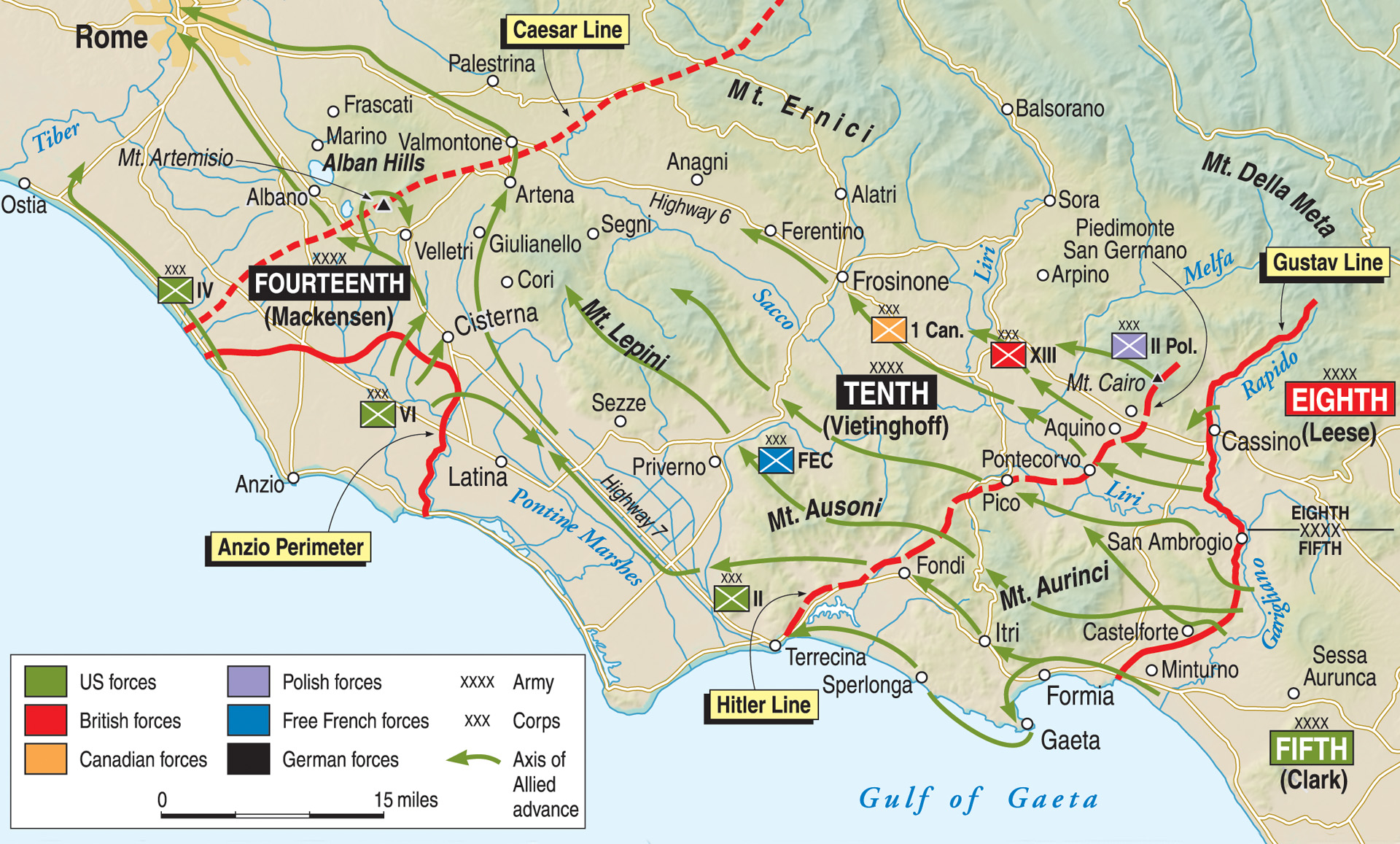

Operation Diadem called for the Polish II Corps to capture the heights of Monte Cassino, site of a ruined Benedictine Abbey where the Germans occupied a seemingly impregnable defensive position. Additionally, the British XIII Corps was to make the decisive push across the Rapido River and through the town of Cassino before assailing the Hitler Line fortifications. The French Expeditionary Corps was expected to slug its way across the Aurunci Mountains, while the rest of U.S. General Mark Clark’s Fifth Army would protect the left flank of the Eighth Army, under British General Oliver Leese (famed Eighth Army commander General Bernard Law Montgomery had departed the Mediterranean Theater in early 1944 for England, where he participated in the planning for the D-Day landings), during the drive toward Rome. The VI Corps, which had languished at Anzio since January, was to break out of its beachhead, seize Highway 6 by capturing the town of Valmontone, and cut off the retreat of General Heinrich von Vietinghoff’s German Tenth Army.

When the details of Diadem were unveiled, Clark was immediately taken aback. It was clear that his Fifth Army was being assigned a subordinate role to that of the Eighth, which consisted primarily of British and Commonwealth troops. The Fifth Army front at Cassino was reduced to 12 miles, while the Eighth was to operate on a line extending across the Apennine Mountains to Cassino.

Clark was determined that his Fifth Army, primarily American troops, capture the Eternal City, and his desire to enter Rome in triumph was at odds with Alexander’s objective of trapping and destroying all German forces in southern Italy. However, a recent conversation with Prime Minister Winston Churchill had a profound effect on Alexander. Churchill’s words still rang in his ears. “I wish you would explain to me why this passage by Cassino, Monastery Hill, etc., all on a front of two or three miles, is the only place which you must keep butting at. About five or six divisions have been worn out going into those jaws.”

Operation Diadem was conceived to increase pressure on the Germans by attacking at multiple points. Alexander probably reasoned that several divisions of the Fifth Army had been roughly handled during eight months of fighting since the landings at Salerno the previous September. The Eighth Army front had been relatively quiet for a while, and though some Eighth Army troops had previously been transferred to Cassino the remainder were fresh, relatively speaking. Their deployment might produce the necessary breakthrough.

Hot under the collar, Clark cornered Alexander two weeks before the scheduled launch of Diadem and voiced his objections to the proposed Fifth Army role. Alexander, whose relations with his American counterparts were far better than those of most British senior commanders, placated Clark to a degree, allowing him significant latitude in the tactical deployment of Fifth Army units.

The opening artillery salvos of Operation Diadem took the Germans by surprise. Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, the German theater commander, had underestimated the strength of the Allied units he faced along the Gustav Line. He was also distracted by the possibility of a second Allied amphibious landing like Anzio along the Tyrrhenian coast north of Rome. However, once again proving their resilience, the Germans mounted a ferocious defense, and the going became rough.

At 11:45 pm on May 11, 1944, the British 4th and Indian 8th Divisions put boats into the swift current of the Rapido and immediately came under intense small-arms fire. A shallow bridgehead was established, but efforts to put more substantial spans across the stream in the 4th Division sector were abandoned. Although the Indian engineers did put two pontoon bridges across, only about half the objectives set for the first two hours of the offensive were achieved. However, after the Fifth Army had experienced numerous setbacks, the Eighth was finally across the Rapido in strength. Reinforcements were hurriedly sent across the river.

During the advance of the 8th Punjab Regiment, Sepoy Kamal Ram earned the Victoria Cross when he voluntarily assaulted two of four machine-gun positions to his unit’s front and flanks. Ram destroyed the position on the far right and then silenced the next. With the help of a havildar, he captured a third position, killing or taking prisoner every German soldier in his path. On May 13, Temporary Captain Richard Wakeford of the 4th Battalion, Hampshire Regiment earned the Victoria Cross, capturing 20 Germans and killing several more while armed with only a pistol and supported only by his orderly. Wakeford was wounded in the face and both arms but reached his objective, allowing his unit to continue its advance.

The Fifth Army’s initial thrust on the night of May 11 was spearheaded by the 351st Infantry Regiment, 88th Division with intense artillery support. The 351st’s objective was the town of Santa Maria Infante and the surrounding high ground. To its right, the 350th Regiment was attacking toward Monte Damiano. During its first 45 minutes of advance, the 350th encountered little resistance, but near the village of Ventosa the Germans stiffened and the objective was not taken for several hours.

Near Monte Damiano, Staff Sergeant Charles W. Shea, leading a platoon that was pinned down by German machine-gun fire, crept forward alone and flipped grenades into the enemy position. Four Germans surrendered, and Shea moved on to a second machine-gun nest. He captured two enemy soldiers and scampered toward a third machine gun. Ignoring enemy fire, he killed the three Germans in that position. Shea’s singlehanded assault earned him the Medal of Honor and cleared the way for his battalion to capture the summit of Monte Damiano and beat back German counterattacks.

The 351st Infantry, in combat for the first time, ran into trouble in a vicious firefight with the German 94th Infantry Division. One company lost 89 men, about half its combat strength. Another 90 troops were cut off and nearly overrun at Tame, a cluster of houses 400 yards from Santa Maria Infante. Concentrated artillery fire saved these troops temporarily.

Just after sundown on the 12th, a group of German soldiers approached the position shouting, “Kamerad!” The Americans came forward to accept the supposed surrender only to find themselves surrounded, victims of a German ruse. All of the Americans were captured, except five men who pretended to be lying dead in their foxholes.

Elements of the 85th Division encountered equally heavy German fire while attempting to capture an S-shaped ridge near Santa Maria Infante. Assaulting high ground on the left of the 88th Division, these troops took heavy casualties and made little headway. First Lieutenant Robert T. Waugh of the 339th Infantry received the Medal of Honor for taking on six German bunkers. Waugh threw white phosphorous grenades into the first bunker and gunned down a group of Germans as they retreated. He then proceeded bunker to bunker and repeated the process.

Along the II Corps line, American gains were negligible. Combined with the limited British gains on the Rapido, the first 24 hours of Operation Diadem appeared to have achieved little.

The French Expeditionary Corps, under General Alphonse Juin, had fortuitously been tasked with the advance across the Aurunci Mountains. So confident were the Germans that the difficulty of the terrain would dissuade any assault rather easily, they had placed relatively few troops in this area of the Gustav Line. The Algerian and Moroccan soldiers of Juin’s command were quite familiar with such rugged country. The Moroccans were generally known as Goumiers, basically professional soldiers enlisted from the Berber tribes inhabiting the Atlas Mountains of their North African country. They were fierce warriors who typically gave no quarter.

The 2nd Moroccan Division encountered stiff opposition in its battle for the heights of Monte Majo as the thinly stretched defenders of General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin’s 71st Infantry Division fought desperately. Before sunrise on May 13, the Moroccans, under General Andre Dody, renewed their attack against the Monte Majo complex. They quickly took Cerasola Hill, Hill 739, and Monte Garofano, scooping up 150 prisoners as they moved forward. German counterattacks slowed the advance on the left flank, but the effective employment of massed artillery paved the way for the Moroccans to sustain their offensive.

The Germans expended their only ready reserve in the vicinity, a battalion of panzergrenadiers, and rapidly it appeared that the entire Monte Majo area might be in jeopardy. A flurry of German radio traffic indicated the gravity of the situation. One intercepted message read, “Feuci has fallen. Accelerate the general withdrawal.”

Within hours of jumping off, the French troops had occupied Monte Majo and raised their tricolor flag on its summit. The threat to the Germans at the Gustav Line was painfully obvious. The 71st Infantry Division had been split in two, opening the left flank of the XIV Panzer Corps to attack. The potential existed for a continuing advance across the ridges running to the northwest. The French were also positioned to attack the German right flank in the Liri Valley, providing a decisive boost to the elements of the Eighth Army just beyond the Rapido. The French might also knife into the Liri Valley and trap many of the Gustav Line defenders.

While Kesselring scrambled to reinforce the 71st Division, the British managed to throw a third bridge across the Rapido and expand their bridgehead up to 2,500 yards. Renewed attacks by elements of the American 85th and 88th Divisions were held up by entrenched defenders on high ground at Hill 109 and Hill 131, but after dark they were surprised when a follow-up advance encountered only sporadic small-arms fire. The Germans were pulling out.

Meanwhile, the French moved forward toward the coveted Liri Valley. Allied air attacks continued to disrupt German communications, seriously hampering German efforts to stabilize the defensive line. Santa Maria Infante fell to the 351st Infantry on the afternoon of May 14. The next day, troops of the 85th Division captured a key road junction beyond the Gustav Line, outflanking German troops defending Highway 7. Although these two efforts had cost General Geoffrey Keyes’ U.S. II Corps and the French Expeditionary Corps more than 3,000 casualties, the strongest defenses of the Gustav Line had been compromised.

On May 15, the Eighth Army succeeded in breaking through the Gustav Line in the Liri Valley. On the 16th, Private Francis Arthur Jefferson of the 2nd Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers grabbed a PIAT antitank weapon and destroyed a German tank that was leading a counterattack. He approached a second tank, clutching his reloaded weapon, but the armored vehicle withdrew before he could come within range. The effort bought time for British armor to arrive and complete the rout of the German attack, while Jefferson later received the Victoria Cross.

The Eighth Army advance on May 15 facilitated a joint attack against Cassino by the 78th Division and the Polish II Corps intended to cut Highway 6 and capture Monte Cassino at long last. Swiftly, the German positions at Cassino became untenable, and the 1st Parachute Division was pulled out of the ruined abbey.

Hesitation at the highest levels of the German command, including Kesselring and Hitler in far-off Berlin, contributed to the rapid collapse of the Gustav Line. General Walter Hartmann, the acting commander of the XIV Panzer Corps, realized that substantial reinforcements would be necessary to contain the Allied breakthrough at three separate points. The failure of German intelligence to accurately assess the strength of the Allied armies confronting the Gustav Line, coupled with the threat of another amphibious landing in the vicinity of Rome, kept Kesselring off balance. Such a slow response ultimately doomed the Germans’ defensive positions south of Rome.

Alexander sensed an opportunity to breach the Hitler Line while the Germans were still reeling and unable to coordinate their remaining defenses. He urged both General Leese and the Eighth Army and General Clark and the Fifth Army to move quickly. Attacks by the 78th Division and the 1st Canadian Division on May 18-19 ground to a halt partially due to stiff German resistance and partially due to the lack of good roads in the area.

The formidable Hitler Line defenses included nine reinforced Panther tank turrets mounting 75mm high-velocity cannons with 360-degree traverse mounted above living quarters for the crews. These, in turn, were protected by outlying antitank gun, machine-gun, and mortar emplacements. In addition, veterans of the earlier battles around Cassino were determined to fight on with grim purpose.

General Juin’s French Expeditionary Corps and General Keyes’ II Corps maintained the Fifth Army offensive. The 351st Infantry Regiment, 88th Division, in the van of the II Corps advance, encountered self-propelled guns and infantry of the XIV Panzer Corps on the Itri-Pico Road, slowing its advance until additional infantry and artillery support could be deployed. The 85th Division rolled along the coastal highway in two columns and into the western foothills of the Aurunci Mountains. The French pressed into the town of Esperia on May 18.

Realizing that the right wing of the Tenth Army was about to be trapped, Kesselring reinforced Vietinghoff with the 29th Panzergrenadier Division and issued orders for a pivoting maneuver anchored on the town of Pico to escape the noose. American forces advancing rapidly on Highway 7 outflanked German positions near the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea. General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, who had rejoined his XIV Panzer Corps command, could only deploy a rear guard to cover a labored withdrawal from the vulnerable positions.

Clark urged Keyes to drive up the coast road as fast as possible to finally link up with the VI Corps, which would hopefully be fighting its way inland from the Anzio beachhead. Meanwhile, Leese was completing preparations for an Eighth Army frontal attack on the Hitler Line. Following the capture of Monte Cassino, the Polish II Corps had advanced four miles by the 19th and was poised to attack the town of Piedmonte San Germano at the southern end of the Hitler Line. The I Canadian Corps was positioned for the primary thrust at Pontecorvo with assistance from the 78th Division at Aquino. The 8th Indian and 6th Armoured Divisions moved into positions to exploit any gains.

On May 20, the first penetration of the Hitler Line occurred when the French hit the Germans hard. Supported by tanks, the 3rd Algerian Division battered the 26th Panzer Division and entered Pico. The defense of Pico, the critical pivot site for withdrawal from the coast, had compelled Vietinghoff to bring elements of the 15th and 90th Panzergrenadier Divisions out of the Liri Valley. Therefore, they were not available to defend against the frontal attack of the Eighth Army. Even worse, the Germans were not in a favorable position to oppose Keyes as the II Corps raced hell-for-leather toward Anzio and the linkup with VI Corps.

The Canadian 1st Division launched Operation Chesterfield on May 23, hitting Pontecorvo at 8:10 am. A day of hard fighting in rain and fog brought victory for the Canadians, who breached the Hitler Line northeast of the town. At the same time, the Germans refused to budge from Aquino and continued clinging to Highway 6, the best road in the Liri Valley. They captured 540 Germans, but the Canadians had suffered more than 500 casualties themselves at Pontecorvo. On the 24th, the Canadians bridged the Melfa River, reaching within five miles of their common goal with the French, the town of Ceprano. The battered Germans pulled out of Aquino on the 25th.

The towns of Fondi and Terracina were the keys to the Hitler Line in the II Corps sector. The 3rd Battalion, 349th Infantry moved rapidly and secured Fondi after the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Walter B. Yeager, left a small force south of Fondi and led a platoon of tanks along with the bulk of the battalion’s infantry into the neighboring hills. Yeager hit the weakened German positions along Highway 7 and then skirted northward to cut the enemy’s east-west communication lines. Troops of the 350th Infantry Regiment killed 40 Germans and captured 65 more at Monte Alto, ranging far ahead of supporting units on their flanks. The regiment’s supply line across treacherous mountainous terrain was kept open for 48 hours until two other regiments of the 88th Division drew close on the right and the French joined up to consolidate the front.

Following an abortive seaborne effort to take Terracina, troops of the 337th and 338th Infantry Regiments, 85th Division fought for two days to capture the town. American troops also moved to cut Highway 7 and prevent the Germans from retreating. However, sensing that time was running out, the garrison evacuated on the night of May 23.

For the Germans, the situation in southern Italy was unraveling at a dizzying pace. The II Corps was in position to advance smartly up Highway 7 to a junction with the VI Corps at Anzio, while the Eighth Army was through the Hitler Line and well into the Liri Valley. The French Expeditionary Corps threatened to complete the encirclement of elements of two German armies, the Fourteenth and the Tenth. Its advance toward the town of Frosinone, astride Highway 6, might potentially split the German armies in two.

On May 25, Vietinghoff ordered a general withdrawal of German troops along the southern front. The LI Mountain Corps vacated its positions opposing the Eighth Army, retreating northward along numerous routes parallel to Highway 6. The XIV Panzer Corps withdrew northeast of Pico to the Sacco River Valley.

During four months of agony, the VI Corps had suffered and bled in the perimeter of the Anzio beachhead. Its strength had grown from two divisions to seven, but the beachhead was constantly under the watchful eyes of Germans in the Alban Hills. Any appreciable movement during daylight hours was sure to bring down a torrent of accurate enemy artillery fire. Some Allied soldiers remember an absolute inability to move about during the day and the necessity of feeding the men under cover of darkness. The identities of replacements put into the line were often known only vaguely to their noncommissioned officers.

“We didn’t get to know replacements,” one sergeant remembered. “When they came in, we hardly knew their names. We rarely saw their faces since we didn’t move around in daylight.”

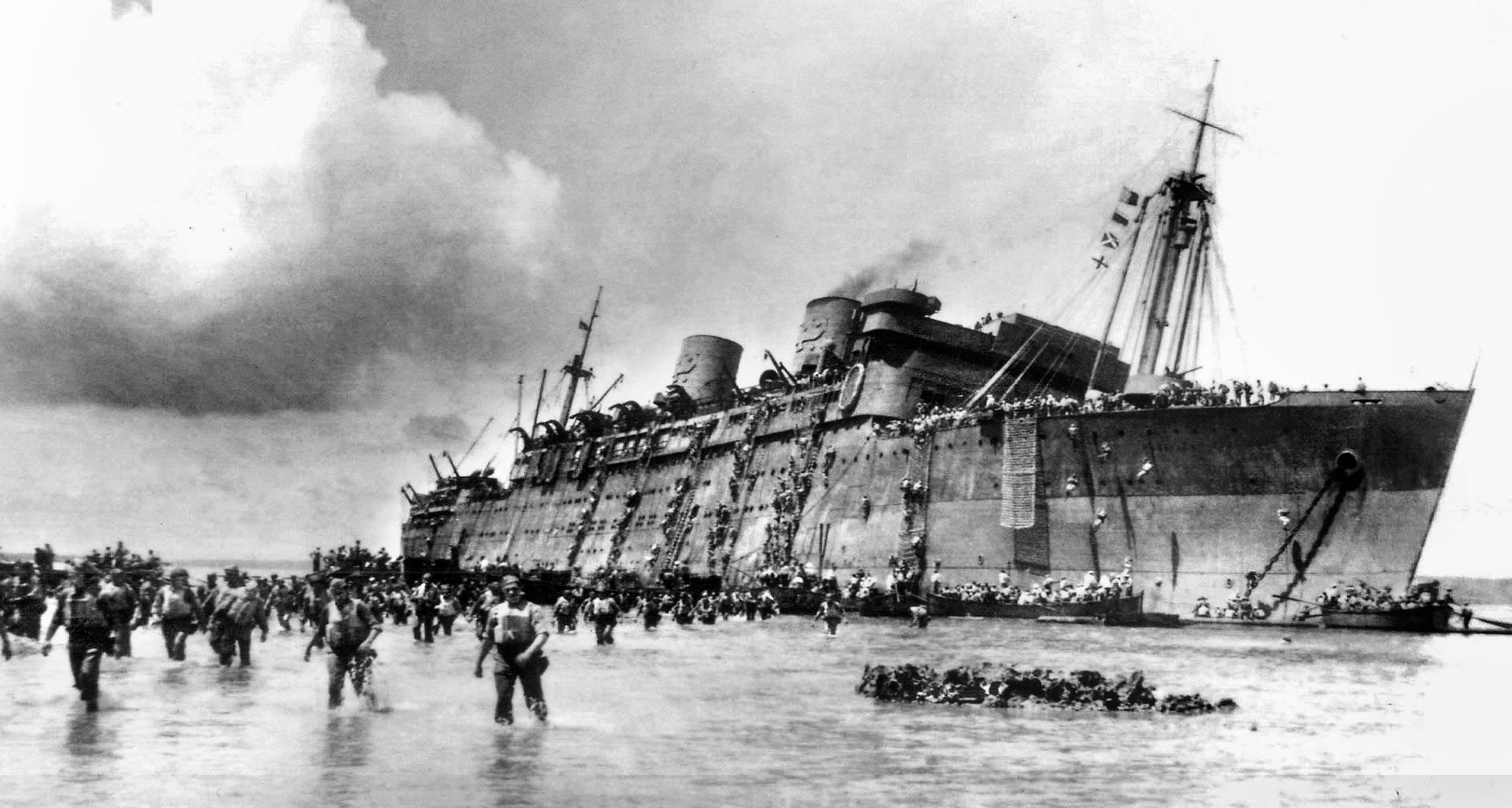

Although the high hopes with which the Anzio landings, Operation Shingle, had been launched in January were only a distant memory by the spring of 1944, a good measure of the scant resources available in the Mediterranean Theater had been allocated to the beachhead in preparation for the opportune time to launch a breakout effort. With the forceful General Lucian Truscott in command of VI Corps following the relief of General John P. Lucas, Alexander expected success.

Clark had ordered Truscott to prepare for any of four eventual axes of attack. The one that aligned with Alexander’s plan, Operation Buffalo, was to strike northeast through Cisterna to Valmontone, cutting Highway 6 and hopefully trapping a large number of German troops to the south. The capture of Rome would be a secondary consideration when compared to the opportunity to cripple enemy forces in Italy. Alexander had originally advocated a movement to the north, through the natural barrier of the Alban Hills and on to Rome, but the prospect of cutting off large numbers of German troops appeared to be of greater benefit. Since the two options for the offensive were at least 20 miles apart, Alexander did not believe they could be accomplished simultaneously.

Clark, however, had his eyes firmly fixed on Rome. He doubted that the seizure of Highway 6 would accomplish much in slowing a German withdrawal over numerous secondary roads around Valmontone. Clark also thought that moving on Valmontone was designed primarily to relieve pressure on the Eighth Army in the Liri Valley. Still, if Clark could make contact with the VI Corps, then an energized Truscott might advance rapidly northward through the Alban Hills and take Rome. Clark desperately wanted to burnish American prestige with the capture of the Eternal City, and time was of the essence. Rome had to fall before Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy, took place on June 6, 1944, and once and for all relegated the Mediterranean to a backwater.

Clark believed, not without reason, that an enemy force anchored on the Alban Hills posed a threat to any Fifth Army movement eastward. He stressed that the Alban Hills should be secured before a drive to Valmontone. Logically, if the Alban Hills, the last natural barrier south of Rome, could be taken, then Rome itself would swiftly fall. The VI Corps, therefore, would be the spearhead of Fifth Army’s drive to take the Italian capital. Aside from several practical reasons for Clark to favor a direct move on Rome, the city had been the focal point of the entire Italian campaign. For months, Alexander had voiced his preference for a drive to Valmontone. However, he had refrained from issuing a direct order.

“Clark, like many other Allied commanders and the British Prime Minister himself, regarded the city as the ‘great prize’ of the entire spring offensive—indeed of the whole Italian campaign,” wrote historian Sidney T. Mathews. “He had told Truscott that it was the ‘only worthwhile objective’ for the VI Corps. Clark had only an incidental interest in the military value of the Italian capital—its airfields and its role as a communications hub (‘All roads lead to Rome’). He wanted Rome because of the prestige associated with capturing it and the success such a feat would symbolize. In recompense for all the frustrations of the winter stalemate in the south of Italy and for the fact that, in Clark’s opinion, the Fifth Army had borne the brunt of the fighting, Clark felt his men deserved the honor. Allied strategy, which had exaggerated the value of Rome out of proportion to its military importance, must be taken into account in explaining the emphasis Clark put on taking the city. Capturing Rome would represent to the people in the United States tangible evidence of American success in Italy, a dramatic event which could be more easily grasped by the American public than the destruction of large numbers of the enemy. Clark also wanted Rome in the shortest possible time because he suspected that Alexander wished the Eighth Army to share in the triumph.”

On the night of May 22, the British 1st Division initiated the breakout from the Anzio beachhead with a diversionary attack along the Anzio-Albano Road. In the early morning hours of the 23rd, Combat Commands A and B of the U.S. 1st Armored Division launched the main attack. The two commands crossed the rail line to Rome and drove a mile into the defenses of the German 362nd Infantry Division on the first day. They had also reached their first objective, a low ridge north of the beachhead. They had lost 35 dead, 137 wounded, and one missing. Three soldiers, Technical Sergeant Ernest H. Dervishian, Staff Sergeant George J. Hall, and 2nd Lt. Thomas W. Fowler, received the Medal of Honor for gallantry on May 23.

At 6:30 am, the 3rd Infantry Division launched an attack on Cisterna. Major Michael Paulick led a force assigned to cover a gap between the 15th Infantry Regiment and the 1st Special Service Force. Paulick lost two tanks and a tank destroyer to German fire from a group of houses 600 yards beyond a bridge over the Cisterna Canal. He directed three tanks on a wide arc into the enemy rear, and their accurate fire routed the Germans. Paulick then moved to within half a mile of Highway 7 against only light resistance.

After dark, a three-man regimental patrol observed about 60 German soldiers in a wooded area near a road junction. The Americans slipped away and passed the word up the line. In the ambush that followed, the German force was decimated with 20 killed and 37 captured.

Two battalions of the 15th Infantry Regiment worked their way toward the town of Cisterna. The 7th Infantry encountered difficulties with mines and stiff German resistance. The 30th Infantry also had trouble with mines and made sluggish progress. The 3rd Division had lost 107 dead, 642 wounded, 812 missing, and 65 taken prisoner in the first 24 hours of the fight. There had been no decisive breakthrough against German positions, but Clark and Truscott were encouraged that the day’s gains were significant and would facilitate the capture of Cisterna.

The 3rd Division surrounded Cisterna on May 24, but an attack against the town’s north flank was unsuccessful. Supported by tanks, troops of the 7th Regiment fought their way into Cisterna the following morning. The situation was in doubt until late in the afternoon when a machine-gun crew reached an advantageous position and drove away the Germans managing a troublesome antitank gun. A company of infantry followed a tank into the courtyard of the town hall, and the survivors of the German 955th Infantry Regiment, their commander among them, were rounded up. The 1st Special Service Force occupied Monte Arrestino, poised to resume the drive toward Highway 6 and Valmontone, some 10 miles away. Troops of the 3rd Division were also positioned to move northwest and occupy the town of Cori.

Near daybreak on May 25, combat engineers of the 36th Division moved south from Anzio across the Mussolini Canal and made contact with an 85th Division task force. After 125 miserable and frustrating days, the VI Corps was no longer isolated. Now, it was the left flank of the Fifth Army.

General Eberhard von Mackensen, commander of the German 14th Army, saw little prospect for success in staving off the 3rd Division drive for Valmontone. Laborers were busy working to complete as many strongpoints as possible along the Caesar Line, which extended from the Tyrrhenian coast between Anzio and Rome nearly to Valmontone, but the reality of the situation dictated that a protracted defense there would be difficult.

Despite the VI Corps progress toward Valmontone, Clark remined unconvinced that the effort was really worthwhile. Late on the afternoon of May 24, he had gone so far as to ask Truscott if he had considered shifting the direction of his main attack toward Rome. He later commented that Alexander’s directive for the drive to Valmontone had been “based upon the false premise that if Highway 6 were cut at Valmontone a German army would be annihilated.”

By the following day, Clark issued orders to change the VI Corps axis of attack to the northwest and Rome. The 3rd Division and the 1st Special Service Force were to continue toward Valmontone, but the balance of the Fifth Army, the 34th, 36th, 45th, 85th, and 88th Divisions, was heading for the Eternal City.

“Truscott was dumbfounded,” recorded the official history of the U.S. Army. “There was as yet no indication, he protested, that the enemy had significantly weakened his defenses in the Alban Hills. That was, he insisted, the only condition that would justify modifying Buffalo. Nor, unlike Clark, did Truscott have evidence of an important enemy build-up in the Valmontone area…. This was no time, the corps commander argued, to shift the main effort of his attack to the northwest … where the enemy was still strong. The offensive should continue instead with ‘maximum power into the Valmontone Gap to insure destruction of the German Army.’”

Like a good soldier, Truscott made arrangements to change his front. Other high-level commanders, both British and American, were shocked by Clark’s decision. One of them remarked that Clark “overnight threw away the chance of destroying the right wing of von Vietinghoff’s Tenth Army for the honour of entering Rome first.”

At 11 am on May 26, the 34th and 45th Divisions swung northwest toward Rome. Clark reassured Alexander that the tremendous success the Valmontone drive had enjoyed would allow both offensive efforts to continue in sufficient strength. Kesselring was initially confused as to whether the new offensive had become the focus for the Fifth Army or a diversionary effort supporting the Valmontone thrust. By the 28th, he was convinced that it was primary when the presence of the 1st Armored Division rolling toward the Alban Hills was confirmed.

German resistance took its toll, slowing Clark’s dash for Rome. On the evening of the 29th, coordinated Fifth Army armor and infantry attacks had succeeded in capturing the railroad station at Campoleone, but the tanks had begun to outpace the infantry, leaving numerous machine-gun nests and pockets of resistance to be dealt with by the infantrymen. In the costly limited advance 1st Armored Division alone had suffered 21 killed, 107 wounded, and five missing. Thirty-seven tanks had been lost to mines, antitank guns, and squads of enemy soldiers with shoulder-fired panzerfaust antitank weapons.

While Kesselring may have been unconvinced that the objective of the new Fifth Army push was actually Rome, Mackensen had seen something like it looming. He chose to strengthen the unfinished Caesar Line. Early on the 29th, elements of the 34th Division attacked German positions in the Caesar Line at Villa Crocetta and Gennaro Hill. Accurate enemy mortar and small-arms fire preceded a strong counterattack that pushed the Americans out of both positions. Giving ground where necessary, the Germans, experts in defensive combat, stood their ground at the most defensible positions in the Caesar Line, guarding the Alban Hills.

While Clark upbraided Truscott for allowing the Germans to consolidate their positions in the Caesar Line, the rest of the Fifth Army made steady progress. The 85th Division was astride the Anzio beachhead, while the French Expeditionary Corps had advanced from the Lepini Mountains toward Valmontone. Nevertheless, Clark, bristling at the possible wait for the Eighth Army to come up for a joint attack, prepared to resume his hammering against the Caesar Line.

The wait probably would have stretched longer than Clark could bear. The Eighth Army encountered stiff German resistance along Highway 6. A 120-foot bridge across the Liri River collapsed, delaying the 5th Canadian Armoured Division for a full day. On May 30, the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, spearhead of the Eighth Army, was near the village of Frosinone, a distant 25 miles southeast of Valmontone. A wide flanking movement by the 8th Indian Division had finally dislodged the Germans from the town of Arce, while the 78th Division moved northwest along routes parallel to Highway 6, expecting to pull even with the Canadians attacking Frosinone.

While his run for Rome appeared throttled temporarily, Clark’s situation was about to improve. On the night of May 27, patrols of the 36th Division had probed the heights of Monte Artemisio, just beyond the town of Velletri. Surprisingly, there had been no contact with German troops on the mountain, although the Hermann Göring Division and the 362nd Division were to have closed the gap in the Caesar Line. Neither could do more than establish a few outposts in the area.

Aware of the dangerous gap, Kesselring voiced his displeasure, and Mackensen reassured his boss that the problem had been handled. Troops from the tired 715th Division and the Hermann Göring Division were ordered to Monte Artemisio, and Mackensen, preoccupied with the threat to his northern flank between Lariano and Valmontone, assumed the gap was closed. But before the German troops arrived, two regiments of the 36th Division were climbing the mountain.

Large numbers of American troops moved quietly through the gap on the night of May 30. Few Germans were encountered, and most of the enemy soldiers died with slit throats. One American related, “Sentries were crawled upon and jumped from the rear. The thumb and the index finger held the German’s nose and the other three fingers of the left hand were placed over the mouth, jerking the head full back, exposing the jugular. Holding the knife in the right hand, the blade was quickly inserted between the vein and the neck bone. As it was pushed through the skin and behind the jugular and air pipes, the knife came out under the chin. The guard bled to death without a sound except bubbles of blood.”

With the 36th Division atop Monte Artemisio and its trailing ridgeline, American artillery observers enjoyed a spectacular vantage point to direct fire against the Fourteenth Army supply lines to Valmontone and Lariano. Mackensen directed his troops to retake the position at all costs. “In a situation of this kind, corps boundaries no longer have any meaning,” he rasped.

Mackensen’s response was already doomed. When he informed Kesselring, the field marshal erupted, sacking Mackensen. General Joachim Lemelsen took command of the imperiled Fourteenth Army.

Clark seized the opportunity to shift the main responsibility for the drive on Rome to the II Corps near Valmontone and poised to advance along Highway 6. Clark requested exclusive use of that key road between Valmontone and Rome, and Alexander agreed. Fifth Army’s three corps could now advance on the Eternal City using both Highways 6 and 7.

The American artillery fire directed from the observers on Monte Artemisio made Highway 6 a shooting gallery. The Germans were compelled to withdraw from Valmontone, which fell to the 3rd Division early on June 2. Kesselring considered making a stand with the XIV Panzer Corps, but the failure to hold Valmontone made the prospect for success unlikely. That night, Vietinghoff ordered the Tenth Army to break contact with the Eighth Army, which had renewed its attacks in the Frosinone area. Kesselring came to the painful conclusion that Rome would be lost.

The Tenth Army withdrawal was an orderly affair, partially vindicating Clark’s assertion that taking Valmontone and cutting Highway 6 would not have trapped large numbers of German troops. Still, had Eighth Army pushed up the Liri Valley more aggressively in combination with the Fifth Army thrust to cut Highway 6, the result might have been a resounding victory.

The VI Corps battle at the Caesar Line in front of the Alban Hills had been costly, in many respects more so than the breakout from the Anzio beachhead. Clark was irked by the slow progress of the 34th and 45th Divisions. However, the 36th Division’s progress threatened to encircle the German troops occupying the Caesar Line. Kesselring ordered a general withdrawal northward as Clark’s VI and II Corps prepared for the final drive into Rome.

On the morning of June 3, Kesselring declared Rome an open city. Hitler decreed that the destruction that had taken place during the retreat from Naples in the autumn of 1943 would not occur again. His directive to Kesselring stated that Rome “because of its status as a place of culture must not become the scene of combat operations.” Clark also made known his “most urgent desire that Fifth Army troops protect both public and private property in the city of Rome.”

Both sides were wary, but every effort was made to spare the city, with its great works of art and ruins that harkened back to the glory of ancient Rome. Vatican City was assured that its neutrality would be respected. The Germans refrained from major troop movements or demolitions of power or water supply centers. Each side’s tactical commanders were given latitude in situations that required action due to military necessity.

At dawn on June 3, the II and VI Corps began their race for the Eternal City. Both made good progress as the German Fourteenth Army pulled back through the Alban Hills and across the Tiber River. The Eighth Army continued attacking. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the 6th South African Armoured Division pounded the 26th Panzer Division near Acuto, forcing the Germans to withdraw under cover of darkness.

Clark’s immediate concern was securing the Tiber bridges, across which his advancing divisions could rapidly pursue the retiring Germans north of Rome. Unaware that the Germans had been instructed not to destroy the bridges, Clark ordered mobile task forces to rush into the city and take control of them as soon as possible.

From multiple points, elements of the 1st Special Service Force, the 3rd Division, and the 88th Division troops of the II Corps entered Rome on June 4. Several ad hoc task forces encountered resistance from concealed antitank guns and even a few German tanks, but by 11 pm all bridges across the Tiber in the II Corps sector were secured intact.

The first VI Corp units to enter Rome were the 2nd Battalion of the 6th Armored Infantry Regiment and a company of the 13th Armored Regiment on the afternoon of June 4. These were followed that evening by the 1st Armored Division, which held the bridges across the Tiber in its zone, and the 36th Division. Commanding the 36th Division, General Fred Walker accompanied his infantry into the darkened city and across the Tiber bridges, already in the hands of his armored troops. “As we moved along the dark streets,” recalled Walker, “we could hear the people at all the windows of the high buildings clapping their hands.”

Five American divisions and the U.S.-Canadian 1st Special Service Force had finally liberated Rome. Rather than halting, they had moved on to harass the Germans on the morning of June 5 along a 20-mile front from the mouth of the Tiber southwest of Rome northeast to its confluence with the Aniene River.

Columns of Fifth Army troops and vehicles streamed through the streets of Rome after daybreak. Finally, the citizenry emerged from their shuttered homes and hiding places, and a tremendous celebration began. Strangers embraced amid a sense of both joy and relief. Clark arrived in Rome late on the afternoon of the 4th and posed for a photo opportunity. The following day, he called his corps commanders and staff officers together at the city hall atop the famed Capitoline Hill. The officers surveyed the continuing scene of wild celebration. Each one of them, though, realized that the moment was fleeting. The commencement of Operation Overlord was just hours away.

Operation Diadem had broken the back of the stubborn German defenses in southern Italy. In a little more than three weeks, the Fifth and Eighth Armies had driven the enemy from the Gustav Line, linked up with the Anzio beachhead, and captured Rome. The price had been high. Allied casualties totaled nearly 44,000, while the Germans had suffered more than 38,000 killed, wounded, or missing plus 15,600 taken prisoner.

When Alexander received news of Clark’s decision to redirect the bulk of VI Corps from Valmontone toward the Alban Hills, he had accepted the development, realizing that he could do little to change the situation. He did comment later on what might have been a lost opportunity. “If he [Clark] had succeeded in carrying out my plan the disaster to the enemy would have been much greater; indeed, most of the German forces would have been destroyed,” Alexander reflected. “True, the battle ended in a decisive victory for us, but it was not as complete as might have been…. I can only assume that the immediate lure of Rome for its publicity value persuaded Mark Clark to switch the direction of his advance.”

In a note of supreme irony, historian Sidney T. Mathews asserts that for several days at the end of May German forces were too weak to contest a drive to Valmontone by VI Corps, even by a secondary effort. Had Clark continued northeastward as Alexander ordered and cut Highway 6, Fifth Army would probably have reached Rome more quickly than by bludgeoning directly at the Caesar Line and then benefiting from the gap discovered by the 36th Division patrols.

German Army Group C had been battered and beaten, but it had not been destroyed or surrendered. The fighting in Italy continued for months. Inevitably, after a splash of headlines celebrating the fall of Rome, the eyes of the world turned to Normandy. June 6, 1944, dawned the longest day on the coast of France, and the campaign in Italy slipped toward twilight.

Michael E. Haskew is the editor of WWII History Magazine. He has researched and written about history-related topics for more than 35 years. He is also the author of West Point 1915: Eisenhower, Bradley, and the Class the Stars Fell On, published by Zenith Press in 2015.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments