by Edward L. Bimberg

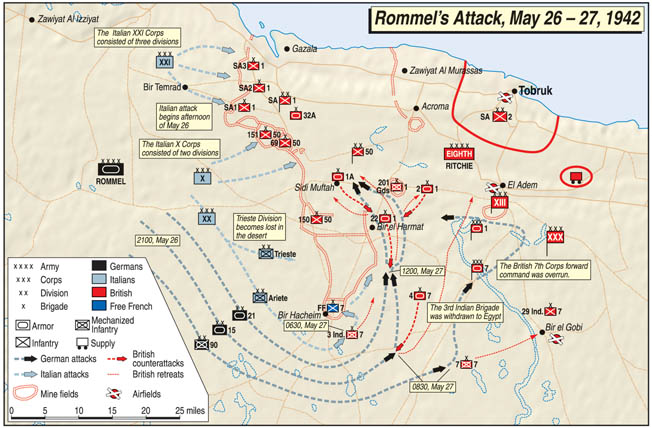

When Brig. Gen. Joseph-Pierre Koenig, commander of the 1st Free French Brigade, surveyed the area he had just been ordered to defend, he must have been mightily discouraged. It was at the end (and most desolate part) of the so-called Gazala Line, a yet to be completed series of British Eighth Army defensive positions that were strung out through the Libyan desert, from Ain-el-Gazala on the Mediterranean coast to Bir Hacheim some 40 miles inland.

The Ever-Unappealing Desert Outpost

At first glance the Bir Hacheim position appeared almost indefensible. The terrain was sandy desert, open and flat, without natural cover or concealment. Atmospheric conditions were as bad as any in the Sahara—burning sun by day, frigid cold at night, plus sandstorms, mirages, and flies. It was arid with no water.

In Arabic “bir” means “well,” but the wells at Bir Hacheim had been dry for a long time. All that remained were some broken-down concrete cisterns and the ruins of a tiny Italian fort that had been the headquarters of a company of meharisti, the Italian-led native camel corps. After a long abandonment, it became the temporary home of the Eighth Army’s 150th Indian Brigade, which Koenig’s French had come to relieve.

Beyond the crumpled ruins was sheer desolation, seemingly endless sand, rock, and gravel with an occasional stretch of camel thorn scrub to break the monotony.

Giving The British A Difficult Time In North Africa

It may have seemed to the French that they were getting the dirty end of the stick when they were assigned to this outlying and apparently unimportant section of the line. Perhaps they were, for the British officers of the Middle East Command in Cairo were inclined to look down on French soldiery in general; the French surrender of 1940 still loomed large in their minds. Until now most of the duties of the small Free French force serving in North Africa had, with a few exceptions, been minor and subordinate to the British presence. The British brass seemed to think that the main effort against the Gazala Line would be farther north than Bir Hacheim, and that is where they had planned their stronger defenses.

The British themselves never seemed able to keep their act together after their brilliant victories against the Italians almost two years before. Ever since German General Erwin Rommel and his Deutches Afrika Korps (DAK) had been sent to North Africa in early 1941 to bolster the sagging Italians, the lines of battle had been swaying back and forth across the area known as the Western Desert. This battleground was comprised of the western part of Egypt and most of neighboring Cyrenaica, the eastern province of Italian Libya.

Recently the British had had the upper hand when their Operation Crusader had driven Rommel’s German and Italian divisions all the way back to El Agheila in western Cyrenaica, but the reinforced Axis troops, now dubbed Panzer Armee Afrika, were making a comeback. By the end of 1941, they were beginning to slowly but surely push the British back toward Egypt once again.

The Depleted British Eighth Army Gets Pushed Back

The British were now in a bad way. The Western Desert Force, renamed the Eighth Army, had been stripped of manpower, first to reinforce the Allied contingent in Greece and then to prop up the forces in the Far East when Japan declared war. It was also short of supplies due to recent naval reverses in the Mediterranean. To add to its difficulties, the Army had a new commander, Maj. Gen. Neil Ritchie, a staff officer without much field experience. As a result, Rommel managed to push the Eighth Army back to the defense line that was being prepared from Ain-el-Gazala to Bir Hacheim. There he halted west of the line to reorganize and prepare for an overpowering spring drive.

Actually, the Gazala Line was not an uninterrupted line of World War I-style trenches, but rather a series of strongpoints called “boxes” that wound southward across the desert for some 40 miles, from the coast to the French-held Bir Hacheim box and then northeast again for another 20 miles.

General Koenig: WWI Vet And Foreign Legionnaire

Since January 1942, when he had first seen the barren expanse of desert he was expected to make into a fortress, General Koenig had kept busy. He was a typical French colonial soldier—44 years of age and an officer since he was 19, a decorated veteran of World War I and a Foreign Legion fighter in World War II. Tall, fair, blue-eyed, with a thin military mustache, he was a distinguished figure in his British-issue khakis and black, gold-trimmed French kepi—and he was tough as nails.

Koenig had assembled under him in the 1st Brigade de Française Libre (BFL) as varied a force of fighting men as could be found anywhere in the multicultured, polyglot Free French army. The core of Koenig’s force was two battalions of the 13th Demi-brigade of the French Foreign Legion (DBLE). This band of exiles was now more cosmopolitan than ever, the prewar colonial veterans from North Africa having been reinforced by defeated Spanish Republicans and refugee Jews, Poles, and other Europeans driven from their homes by Adolf Hitler.

The 13th DBLE was raised at the very beginning of the war. It fought in Norway and was one of the few French units to rally to de Gaulle en masse when the call came. Now its commanding officer was Lt. Col. Dmitri Amilakvari, a Georgian prince who had made service in the Foreign Legion his life’s work. But unlike most mercenaries who give little thought to the nationality of their employer, Amilakvari actually loved France and told his men that dying for their adopted country was a great privilege. How seriously they took this advice is not known, but apparently they were willing to give their lives for Amilakvari and the Legion, if not for France. The history of the 13th DBLE will attest to that, for even before Bir Hacheim the Legionnaires had fought not only in Norway, but in Eritrea and Syria as well, and several of them had died.

Two Clergymen Face Off Across The Battle Line

Second to the Legion in World War II battle experience were the two companies of the 1st Bataillon d’Infanterie de la Marine (BIM), French Marines who considered themselves just as tough as the Legionnaires. It might seem strange that men who were recruited largely from among Breton fishermen and others of a very salty background would find themselves at Bir Hacheim in the waterless Sahara, but the Marines had a long tradition of overseas service. In fact, those infantry regiments of the French Army designated “colonial” were originally recruited from the Marines.

Another oddity of this particular unit was that their leader, Commandant Savey, was actually a Catholic priest who had commanded them while they were attached to the British in much of the previous desert fighting. Perhaps his religious vocation was not so odd after all, since on the other side of the line Major “Papa Willi” Bach, the German artillery officer whose defense of Halfaya Pass had won him fame, was also a clergyman—an Episcopalian priest.

Even stranger was the 2nd Demi-brigade Senegalaise, commanded by Lt. Col. de Roux, whose two battalions were drawn together from opposite ends of the earth. The 2nd Bataillon de Marche de l’Oubangui (BM2) was made up of proud black soldiers recruited from the Oubangui-Shari province of French Equatorial Africa. They were largely illiterate, and many of them had never worn shoes before their induction into the French Army, but they learned fast and made excellent soldiers.

The Accuracy Of French Artillery Makes Up For Their Number And Caliber

The other battalion of the so-called “Senegalese” Demi-brigade had its origins far from the Dark Continent. The 1st Bataillon Pacifique (BP1) came from that fabled tourist paradise, the scattered islands of the French South Pacific. Bir Hacheim must have been a terrible shock to them, but they too, learned to adapt in a hurry.

The main artillery support was supplied by a regiment of 75mm field guns under the command of Lt. Col. Laurent-Champrosay, supplemented by a company of antitank guns. Although far outweighed in number and caliber by the German guns, the accuracy of the French artillery would come as a nasty surprise to the attackers.

The antiaircraft defenses at Bir Hacheim were assigned to the 12 Bofors 40mm cannon and the machine guns of another complement of Marines, the 1st Bataillon de Fusiliers Marins (BFM), under command of Capitaine de Corvette Amyot d’Anville. An additional six Bofors were manned by British gunners. Engineering know-how was furnished by the 1st Compagnie de Sapeurs-Mineurs, while administrative chores were taken over by Koenig’s staff. Later, some of the Marines were transferred to a commando outfit and were replaced at Bir Hacheim by a company of North Africans, adding to the cosmopolitan nature of the garrison.

Legionnaires’ Engineering Experience Comes In Handy

As they faced each other across the desert, both sides were gearing up for an assault. By this time Rommel had built himself such a reputation that the Allies feared he would strike first and Koenig knew he had little time to get his defenses in order. However, he had the skill of his engineers to plan the field fortifications—and the Legion to build them. In prewar North Africa, the French Foreign Legion was known for its great civilian construction projects throughout that part of the French Empire. Roads, bridges, tunnels, forts, all had been built by Legionnaires, most of the time using only pick and shovel and their own sweat.

The Legionnaires hated those jobs. They thought they were beneath the dignity of warriors, but they were ordered to do them, and they learned how to do them well. That on-the-job education came in handy as they dug trench systems, built pillboxes, and fortified command posts, strung miles of wire, and laid thousands of mines. This time they did not mind the labor, for they knew that the enemy was at the gates.

The others were also working. The field artillerymen were registering their pieces, the ack-ack gunners sandbagging revetments for their Bofors, the infantry positioning their machine-gun nests. All were constantly digging under the most miserable of desert conditions.

The Fortification Project Is Completed, Despite The Harshest Desert Conditions

North Africa is said to be a cold land with a hot sun, and during the daylight hours the temperature was usually over 100 degrees. When night fell and the curtain dropped suddenly in the Sahara, the air did not just cool off, it became frigid, and men were shivering from the cold a very short time after suffering the torment of a blazing sun. To make matters worse, the ghibli, the constant, annoying desert wind, could turn without warning into a roaring, stinging sandstorm that might last for hours or even days. When the sky clouded over and day turned into night, the wind reached almost hurricane force, work ceased, and men sought shelter in gun pits or trenches.

At last, in spite of all the difficulties, General Koenig felt that the Bir Hacheim fortifications were complete and its garrison, some 3,700 strong, ready for anything. In addition to its defensive strength, the 1st Free French Brigade had the offensive capabilities of its “Jock columns,” heavily armed mobile units that patrolled between the widely spread out boxes of the Gazala Line. British Jock columns (named after Brig. Gen. “Jocki” Campbell, who developed the technique) used their newly acquired American 18-ton Grant tank with its powerful 75mm gun as the principal patrol weapon.

French Jock Columns Were Grateful For British Castoffs

The French Jock columns, lacking tanks, were quite different. They usually relied on truck-borne infantry with a few light AA guns, plus a towed 75mm or antitank gun to protect against the panzers. They might also use the lightly armored tracked vehicles called Bren gun carriers supplied to them by the Eighth Army. The British themselves did not care too much for the sometimes mechanically unreliable and under-gunned carriers, but to the equipment-starved French they were luxury itself, and they were delighted to have them.

Within the Bir Hacheim perimeter, which was roughly triangular in shape and more than 16 kilometers around, the troops were positioned so that the Senegalese manned the northwest corner, with the Pacific Battalion in the southwest. One of the Legion battalions (BLE 2) was located at the point of the triangle, while the other (BLE 3) was in the center along with Brigade Headquarters and the artillery. BLE 1 was not in the game, since there had not been enough materiel available to the Free French to properly equip it for the Bir Hacheim defense. The ancillary troops, including the North Africans, were spread throughout the encampment. None of the garrison was entirely static, however, but were kept busy operating the Jock columns that continued to patrol the desert tracks.

By the end of May, General Ritchie was finally in a position to launch his Eighth Army offensive from behind the Gazala Line. But Rommel, reorganized and resupplied, beat him to the punch. On May 26, while Ritchie was still thinking about it, Panzer Armee Afrika attacked.

The Desert Fox Swings Wide Around Bir Hacheim Box

The Axis troops first struck the Gazala Line in the north, but this was just a feint. The next day Rommel led the bulk of his mobile forces south in a wide sweep around the Bir Hacheim position to attack the strongly held British “Knightsbridge” box, halfway back to the coast. On the way his powerful forces smashed several isolated British brigades before he hit the main British force.

Apparently the Desert Fox had purposely avoided the Bir Hacheim box by swinging wide around it, figuring that these weak Frenchmen stuck out at the end of the Gazala Line could easily be taken care of later, after he had defeated the British. He merely sent a few light armored units to probe the French position.

The probe discovered that Bir Hacheim was not the pushover that Rommel thought it would be. It was, in fact, a hornets’ nest.

Rommel Sends Italians Toward the French Position

When these ill tidings were reported to Panzer Armee headquarters, Rommel immediately ordered two Italian divisions, the Trieste Mechanized and the Ariete Armored, to attack, fully expecting the Frenchmen to surrender within 24 hours. He was in for a nasty surprise.

According to some reports, the Trieste was a bit hesitant in its approach, but the tanks of the Ariete charged in with a will. Soon the smell of cordite filled the air, and clouds of smoke blended with the desert dust of Bir Hacheim as the crash of artillery, the thunk of mortars, and the rattle of machine guns announced the opening of a real battle.

First blood in the siege of Bir Hacheim went to the French. When the smoke cleared, 32 Italian tanks were smoldering ruins, the victims of Laurent-Champrosay’s artillery and antitank guns and more than a few of the 50,000 perimeter mines. The Italians withdrew, leaving behind their wounded, including the colonel of the Ariete’s 132nd Armored Regiment who was pulled from his wrecked tank by his captors. In addition, Koenig ordered his Jock columns out to prey on the nearest Axis supply lines.

After A Temporary Setback, Rommel Eyes Tobruk

Rommel was furious. He had counted on speed and surprise to carry him through the Gazala Line, and now these impertinent Frenchmen were standing in his way. Nor on this same day were things going well with the Axis forces north of Bir Hacheim, where they had run into the tough British defenses of the Knightsbridge box with their new Grant tanks. To make matters worse, the Allied mines were taking a toll of the Axis supply vehicles, and the tank and artillery ammunition was not getting through.

This should have been a time for the British to counterattack, but Ritchie hesitated. It was a big mistake. While the British general conferred with his staff, Rommel reorganized his forces and demonstrated his tactical genius by battering a hole through the British lines north of Bir Hacheim. In doing so he not only opened a path for his supplies, but smashed a British infantry brigade, destroyed more than 100 tanks, and took some 3,000 prisoners. He now had the upper hand again.

The German general, always ambitious, was looking beyond the Gazala Line toward the fortress city of Tobruk, which he had tried to conquer three times before but was still in British hands. Intelligence reports indicated that the garrison at Tobruk had recently been substantially weakened—and beyond Tobruk lay Alexandria, Cairo, and the Suez Canal!

The French Politely Refuse the Italian Demand for Surrender

Such was Rommel’s self-confidence that he thought he could push right on to Suez once he had neutralized Tobruk. He knew that the British were building a last-ditch defensive line at El Alamein, just 50 miles from Alexandria, and if he ever expected to reach Suez he had to attack those defenses before they became too strong. Time was of the essence. To clear the way east he had to take Tobruk in a hurry. But first he had to pierce the Gazala Line.

Rommel now turned his attention to Bir Hacheim. Due to his successes in the north, he now had it surrounded. He first sent a delegation of Italian officers under a white flag to Koenig’s headquarters to demand the surrender of the Bir Hacheim box. With exaggerated politeness the Italians reminded the French general of the hopelessness of his position, encircled as he was by superior forces. Equally punctilious, Koenig replied that surrender was out of the question. In a flurry of saluting, the Italians departed. The date was June 2.

Soon thereafter shells began to fall onto the fortifications of Bir Hacheim, and for the next few days a heavy bombardment was maintained. It was returned by the accurate counterbattery fire of Laurent-Champrosay’s 75s, but French ammunition was limited, and resupply was eventually cut off by the ever-tightening ring of Axis troops.

The Germans And Their Allies Call In Air Support

Rommel also called in the Luftwaffe, and the daytime skies over the French stronghold were filled with Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers, Heinkel He-111 bombers, and Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters. D’Inville’s Bofors fired away, but there was a limit to what the few guns could do against such massive attacks. Altogether, the Luftwaffe flew 1,300 sorties against the French positions.

Later there would be some recriminations against the Allied high command for not supplying more protection against the aerial assault, but the RAF did what it could, arriving daily over the battlefield to challenge the Germans. However, the Hawker Hurricanes and Curtiss P-40s were no match for the concentrated numbers of German planes, and they brought little relief from the constant bombardment. In spite of this, the French were appreciative of their help, and Koenig was said to have sent a message to the British, “Merci pour la RAF.” To which the RAF replied, “Merci pour le sport!”

Supplies Become Critically Low At Bir Hacheim

The constant aerial attacks and artillery bombardment were a cover for continuing attempts by the Germans to infiltrate the French positions. They used both tanks and infantry, but the French troops fought them off. The engineers’ planning and the Legion’s expertise in the initial construction of the field fortifications kept the defenders’ casualties low and their morale high. But it did not help the supply situation, which was rapidly becoming critical. Then, from June 2-5, there was a bit of relief from the Axis pressure when Ritchie finally launched a counterattack in that area north of Bir Hacheim that came to be known as “the cauldron.” The fighting there was bitter, and Rommel had to pull troops from the Bir Hacheim siege to meet the challenge. As usual, the German general outmaneuvered the Britisher and scored a telling victory, destroying more enemy tanks and taking more POWs.

Now Rommel again put the squeeze on Bir Hacheim, this time with heavy attacks by the Trieste Division and the German 90th Light Division. Of interest is that the 90th Light had in its ranks two battalions of German soldiers who, in the not too distant past, had either resigned or deserted from the Foreign Legion and were now fighting against their former comrades-in-arms. Once again the French fought off these attacks, but the crushing air and artillery bombardments continued. Food and water were now running out.

The RAF made attempts to supply the beleaguered garrison by parachute, but the targets were too small and the unpredictable desert winds blew most of the drops into the Axis lines. There was no more ammunition for the 75s.

French Asked To Hold On Just a Little Bit Longer

At this point General Koenig knew he must try to lead his troops out of this death trap, break through the German lines, and join the British who were rallying at El Alamein. When his plans were communicated to Allied headquarters in Cairo, he was asked to hold on just a little longer. The British needed time to put the finishing touches on their El Alamein defenses and reorganize the troops who would man them. Like the good soldier he was, Koenig replied that he would, and went back to fighting his war.

The next few days at Bir Hacheim were hell itself. Rommel, frustrated, ordered even heavier assaults and bombardments. The French troops, exhausted and virtually without food or water and with little ammunition left, fought on. Rommel sent another white flag party to demand surrender or face annihilation, but Koenig refused even to see them. There was no military courtesy this time.

Finally, on June 10, as small groups of Axis troops began to infiltrate the French lines, Koenig decided it was time to break out. He waited for the cover of darkness and then gave the order.

The French Attempt A Quiet Retreat

At first the movement was orderly, as the Legion, the Marines, the Senegalese, and the rest of the polyglot garrison filed silently through gaps in the minefields in disciplined squads and platoons, undiscovered by the enemy. But there were just too many troops in motion for it to remain that way.

When the Germans found out what was going on, the shooting started and all hell broke loose. As tracers streaked through the night and undisclosed mines exploded under vehicles, the soldierly files of the 1st Free French Brigade disintegrated into small groups and individuals. Soon they were no longer a cohesive military force, but a band of desperate escapees.

It was every man for himself.

The French soldiers were still armed and dangerous, and as they stumbled through the desert night, their pursuers were still wary of attacking them. Small firefights broke out everywhere as Koenig’s men fought their way northeast toward the British lines and safety.

Rommel Takes The Fortress At Tobruk

General Koenig and Colonel Amilakvari escaped in the general’s car, driven by Susan Travers, an English volunteer assigned to the Free French ambulance section. (Travers is the only woman who could ever be considered a member of the French Foreign Legion, in spite of what has been written in several lurid works of fiction.) They wandered around in the desert most of the night, more than once just missing capture, until they finally made it to safety.

It seemed a miracle, but most of the rest of the garrison of Bir Hacheim also escaped and lived to fight another day. Rommel finally crashed through the Gazala Line and invested Tobruk. His intelligence had been correct; the city’s defenses had been considerably weakened so that more vital areas might be reinforced. After a one-sided fight, the Tobruk garrison surrendered. The Germans occupied the fortress city, and Rommel’s eye turned hungrily toward Alexandria.

Bir Hacheim Would Prove To Be Rommel’s Undoing

He never got there. He had worn himself out on the Gazala Line, and his time table had been seriously upset by the stubborn heroes of Bir Hacheim. The Desert Fox met his ultimate defeat months later at the hands of a cocky new commander of the Eighth Army, Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, known to his troops as “Monty.” But Rommel never forgot Bir Hacheim. He later wrote about the siege: “Seldom in Africa was I given such a hard fought struggle.”

Nor will the French nation ever forget those desert soldiers, for they will live on in the history books. Although to some it may seem a strange sort of memorial, there is today a Metro station in Paris named “Bir Hacheim.”

Great article.

The subway station’s name is actually spelled with a k !