By William E. Welsh

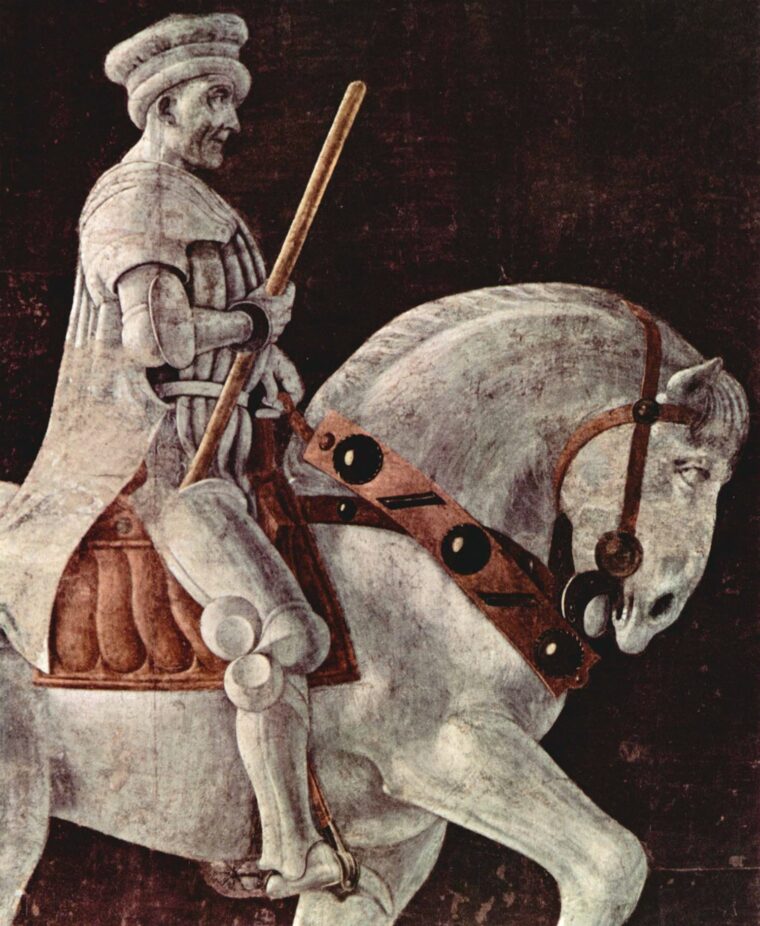

Long columns of heavily armed soldiers streamed southeast along the left bank of the Adige River in the Veneto region of northern Italy on March 11, 1387. Most of the 9,000 English, German, and Italian troops under the command of English Condottiero John Hawkwood tramped on foot, while one-third traveled on horseback. A scorched-earth strategy by the Veronese army, which followed closely on their heels, had compelled Paduan captain-general Hawkwood to make a hasty retreat towards his supply base at Castelbaldo to feed his starving men and horses.

Despite the crisp weather, Hawkwood’s men felt a deep sense of exhaustion. Their morale, however, remained high for they had tremendous confidence in their commander. Most of the men-at-arms wielded shortened lances as pikes, but others bore longbows and daggers. Some of the horsemen wore plated armor and carried lances, others got by with just padded jacks and swords. Hawkwood’s crack English mercenaries exhibited a marked esprit de corps that made them the envy of the other soldiers.

Within just eight miles of his destination, Hawkwood made a bold decision. Instead of trying to get his entire army across a narrow bridge over the rain-swollen Adige, a near-impossible task given the nearness of a Veronese army that outnumbered his force three to one, he would make a stand near the village of Castagnaro. Having made the decision, he set about arraying his army in a manner that would allow him to successfully repulse his opponent’s army.

Hawkwood was the second son of a tanner born on or around 1323 in the Essex village of Sible Hedingham, an old Roman outpost that was situated 60 miles northeast of London. Gilbert Hawkwood, his father, had a thriving tanning business from which he had amassed modest wealth.

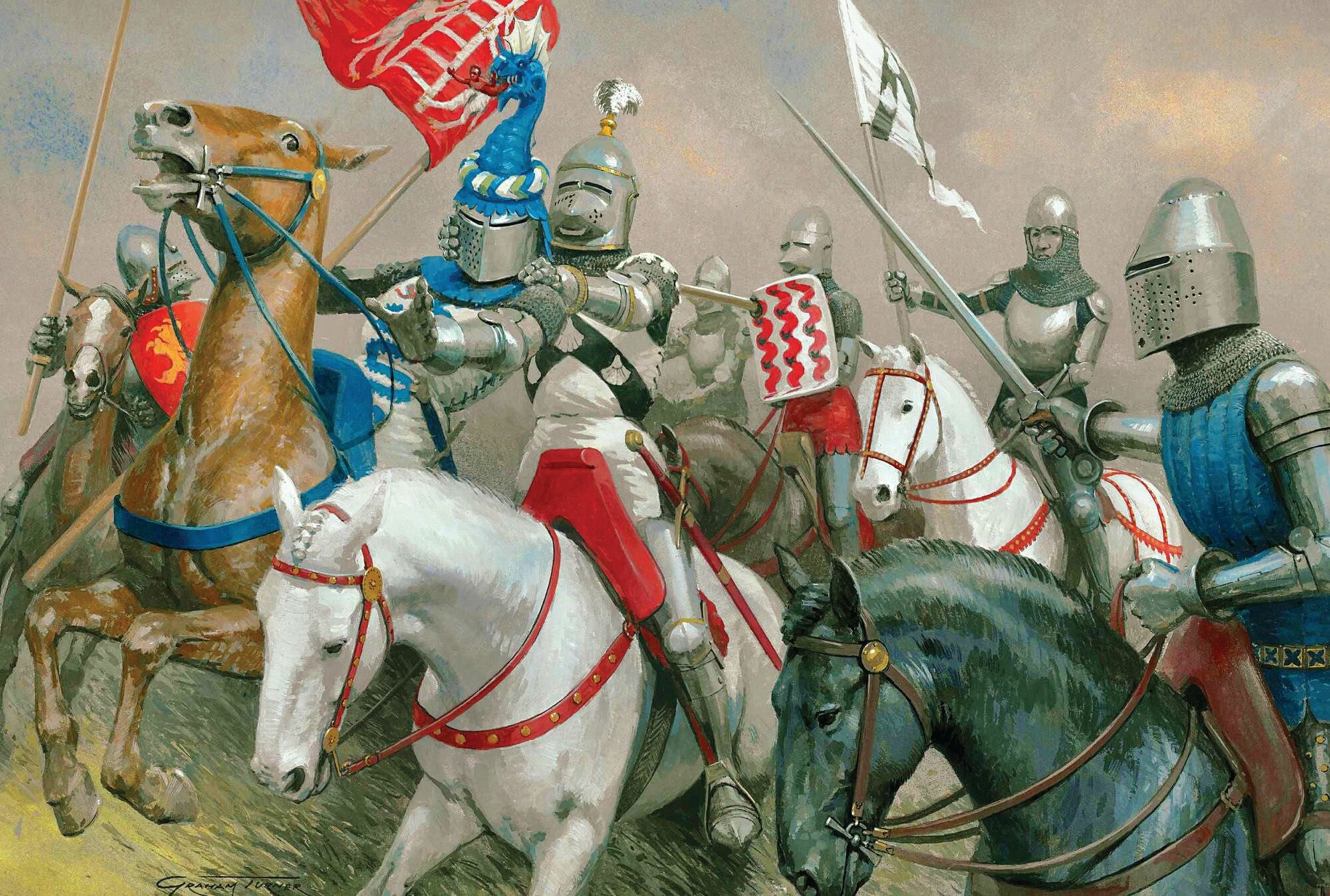

In the early 1340s Hawkwood joined the retinue of William De Bohun, Earl of Northampton, most likely as a longbowman. By that time England had been at war for several years with France. Hawkwood, like many other young men in England at the time, had a keen desire to increase his wealth and standing through military service. English men-at-arms and archers both shared in the plunder accrued while campaigning on French soil.

Indirect evidence suggests that Hawkwood fought under Northampton at Morlaix in 1342 and Crecy in 1346, and later fought in the retinue of John De Vere, Earl of Oxford, at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, in which Edward of Woodstock, the Black Prince, won a decisive victory over the French. Sources are conflicted as to whether Hawkwood was knighted immediately after Poitiers or later during his service in Italy.

Hawkwood joined the throngs of foreign auxiliaries who fought with either the English or French that drifted into the lawless region of southwestern France following the Treaty of Bretigny signed in 1360 that ushered in a nine-year truce in the Hundred Years’ War. The French called the roving auxiliaries routiers. They banded together in so-called free companies for hire by regional lords.

As many as 100 companies of these armed brigands plundered towns and villages throughout France following the truce. Hawkwood joined German Albert Sterz’s Great Company, a veritable army comprising many different free companies. They were “warriors from various lands who assailed other men with no right and no reason other than their own passions, iniquity, malice and hope of gain,” wrote French chronicler Jean de Venette.

In a quest for plunder, the Great Company gravitated towards the papal enclave at Avignon on the Rhone River where the pope had resided since 1305. In a bid to rid France of the routiers, Pope Innocent VI subsequently arranged for the majority of the free companies to relocate to either Spain or Italy where they might find employment as mercenaries.

The pope, in concert with the Genoese, paid the Great Company to assist John II Palaeologus, the Marquis of Montferrat, in his war against the powerful Visconti Dynasty that ruled the Lordship of Milan. Hawkwood was one of 17 corporals commanding contingents that averaged between 150 and 200 mounted men-at-arms and archers that made up the Great Company. Mercenaries were keen to fight in northern Italy because the Italian city-states had grown extremely wealthy as a result of commerce and trade.

Not long after entering Italy, the name White Company replaced Great Company. Although legend has it that the name was inspired by the highly polished, gleaming plate armor worn by its knights, it is more likely that its name came from the white surcoats that the English in particular wore over their armor.

The English and German marauders were willing to do whatever it took to receive a handsome sum of gold coins, observed Florentine chronicler Filippo Villani. “They were young, hot, and eager,” he wrote, “and accustomed to homicides and robbery, current in the use of iron, having little personal cares.” When they finally reached the outskirts of Milan in April 1363, the mercenaries of the White Company amassed 100,000 gold florins through plunder, extortion, and ransoms.

Over the course of the next 33 years Hawkwood would serve at different times as the commander of Pisan, Papal, Florentine, and Milanese armies. In each contract he inserted a provision stating that he would neither fight against other Englishmen nor take actions against the interests of the King of England.

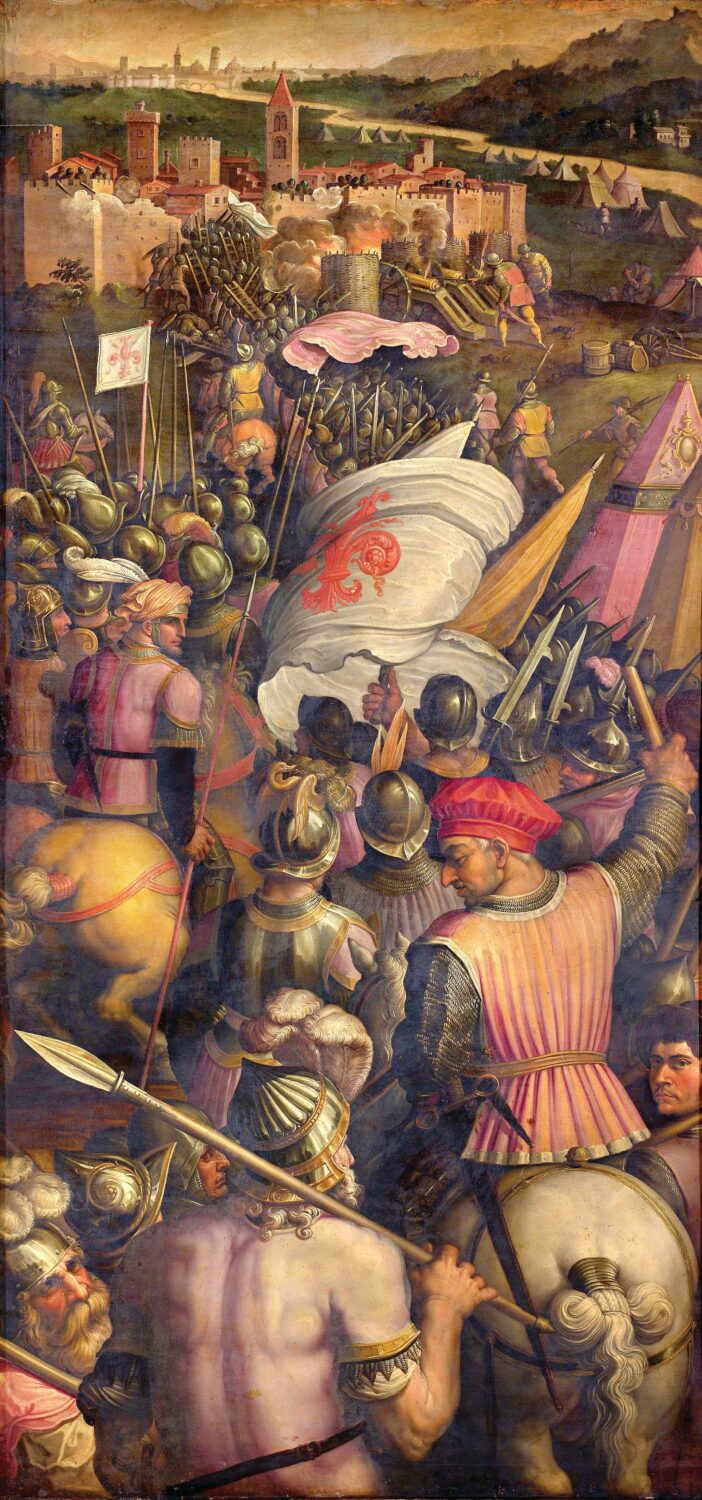

Pisa and Florence went to war with each other in 1362. Florence, although landlocked, was the larger and more powerful of the two republics, and it sought to conquer Pisa in order to possess its ports on the Tyrrhenian Sea. Although Sterz was still the senior commander of the White Company, Hawkwood played a key role in the development and execution of the company’s strategy on campaign. After burning and plundering its way through the Florentine countryside in summer 1363, the White Company won a decisive battle that autumn against the Florentine army at Incisa in Val d’Arno.

The members of the White Company elected Hawkwood that winter to serve as their commander, a move heartily approved by the Pisans. Hawkwood vowed to carry the war to the very gates of Florence. Although most medieval towns were too well defended to carry by storm, Hawkwood intended to burn crops, demolish the suburbs, and probe the city’s defenses. He marched against Florence with a mounted force of 6,500 troops, as well as several companies of sappers.

Hawkwood’s force moved through the outskirts of the city parallel to its walls burning its suburbs and launching periodic assaults on the city’s defenses. The Florentines tried to bribe the English captain to stop the destruction, but he declined the money. Several of his lieutenants, however, accepted bribes and departed with their men. The desertions hollowed out the Pisan army and Hawkwood had no choice but to withdraw to the suburbs of Pisa.

Afterwards, Florentine Condottiero Galeotto Malatesta invaded Pisan territory with a large army. He established a fortified encampment at Cascina on the eastern outskirts of Pisa. Outnumbered by more than three to one, Hawkwood believed his only chance for victory was a surprise attack on the Florentine camp.

With an advance guard composed of his crack mercenaries, Hawkwood stormed the Florentine encampment on July 28, 1364. His dismounted men-at-arms fought their way through the camp’s outer defenses, but were hurled back by waves of Florentine reinforcements. Hawkwood broke off the fight and holed up with his English mercenaries in the fortified Abbey of San Savino. The Florentines proceeded to slaughter the Pisan levies before they could reach the safety of Pisa’s walls. The war concluded with Florence acquiring some additional territory, but the Florentine Republic would not succeed in conquering Pisa for another half century.

Pope Urban V, who preached a crusade against Lord Bernabo Visconti of Milan and who tried to return the Papacy from Avignon to Rome, became a target of Hawkwood when the English captain agreed to lead the Milanese army in 1368. Yet the pope’s German mercenaries inflicted a sharp defeat on the White Company at Arezzo in which Hawkwood was captured. After he was freed for a sizeable ransom, Hawkwood led a column of 2,500 mounted men that harassed the pope by forcing him to repeatedly change his location.

The War of the Eight Saints, which pitted Pope Gregory XI against a coalition comprising the lordships of Milan, Florence, and Sienna, erupted in 1375. Gregory lured Hawkwood away from the Milanese. Hawkwood, though, refused to conduct offensive operations against either Milan or Florence. He had a close relationship with Bernabo Visconti in which he married his illegitimate daughter, and he accepted a bribe from the Florentines not to plunder their lands.

At the start of the conflict, Florentine agents incited rebellion in a number of key towns throughout the Papal States. Hawkwood was one of a number of mercenaries whose troops took an active role in suppressing these revolts.

Infuriated by the Florentines’ success in this regard, Gregory ordered his right-hand man, Cardinal Robert of Geneva, to make an example of one of the rebel towns. Robert directed a company of Breton mercenaries, as well as the White Company, to make an example of Cesena, which was situated 55 miles southeast of Bologna.

Over the course of a three-day period beginning on February 3, 1377, the Bretons massacred several thousand civilians in an unprovoked orgy of violence and plunder. Hawkwood did not actively participate in the atrocities at Cesena, although many of his soldiers did join in the slaughter. The following year the two sides signed a treaty in which the Florentines paid a substantial indemnity to the Papacy, and the Papacy lifted an interdict that had been placed on Florence.

Hawkwood’s greatest battlefield victory came in the service of the Commune of Padua nearly a decade later. Francesco Carrara, Lord of Padua, hired Hawkwood in 1386 to lead his army against a much larger Veronese army financed by the Doge of Venice.

With Condottiero Giovanni Ordelaffi’s much larger army in close pursuit, Hawkwood made a stand at Castagnaro on his retreat back to Paduan territory in March 1387. Hawkwood positioned his men-at-arms and longbowmen in the front ranks behind an irrigation ditch on the left bank of the Adige River. The English archers showered the enemy with their arrows.

The sustained missile fire goaded the Veronese into attacking prematurely, and in their haste the Veronese failed to bring their large complement of artillery to bear against the Paduans. As the battle developed, Ordelaffi found he could neither break the Paduan center nor turn its flanks.

Hawkwood previously had detailed a detachment to fill in dirt over the irrigation ditch near the river for a flanking maneuver. He sent a body of archers backed by most of his 2,400 horsemen across the dirt causeway to assail the enemy’s left flank. Caught by surprise, Ordelaffi was unable to get the troops of his left wing to change front in time to check the assault. The Paduan horse charged the flank and rear of Ordelaffi’s vanguard throwing it into confusion. As the Veronese front ranks crumbled under the assault, the Paduans in the center counterattacked.

At the cost of fewer than 500 casualties, Hawkwood’s army killed or wounded 1,500 Veronese and captured an additional 5,000 troops. Ordelaffi was among those marched into captivity. The victory cemented Hawkwood’s status as one of the great condottiero of the Late Middle Ages.

After his great victory at Castagnaro, Hawkwood left Paduan service to serve the Florentine Republic. But he could not make any headway against a superior Milanese army.

During the second half of his military career in Italy, Hawkwood also tried his hand at diplomacy by negotiating trade agreements for King Richard II of England with the Italian city-states.

Hawkwood died on March 17, 1394. During his long career in Italy, he had amassed considerable wealth and had purchased estates in both northern and central Italy. Richard II requested that the body of what he termed the “most magnificent captain” should be returned to England, but it is unknown whether his bones rest in his first home in England or his second home in Tuscany.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments