By Joseph E. Lowry

During the Civil War, both the North and the South utilized existing technology such as the telegraph and the railroad to further their ongoing war efforts. However, by the third year of the fighting, three pieces of very old technology still figured heavily in the way in which the war was fought, particularly in the eastern theater. These were the axe, the pick, and the shovel. By this time in the war, experienced soldiers on both sides had realized that it was sheer lunacy to stand or charge in mass formations in the face of rifled muskets that could kill effectively at a range of 900 yards.

It took the armies two years of brutal bloodletting to learn this rather elementary lesson, during which time hidebound officers on both sides stubbornly continued to follow the Napoleonic tactic of trying to overwhelm the enemy with sheer masses of troops. Field fortifications were largely eschewed—“Toujours l’audace” was still the catchphrase of the day. The rare times when ground cover was used to mask or shelter troops were more a matter of taking advantage of the natural landscape—the railroad cut at Second Manassas, the sunken lane at Antietam, the stone wall at Fredericksburg—than any preplanned military decision.

All this began to change on the first day at Gettysburg, when Brig. Gen. John Buford’s outnumbered Union cavalrymen built breastworks of fence posts and rocks to delay the attack of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s much larger Confederate division. The efficacy of building such protective cover paid even greater dividends on the second day of the battle, when Brig. Gen. George S. Greene had his New York regiments construct breastworks on the summit of Culp’s Hill. Prior to assaulting the hill later that afternoon, Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s men could clearly hear the ringing of axes as Greene’s men chopped down trees to strengthen their position. The immense benefit of those works was proven when the Union forces easily repulsed Ewell’s attack.

Battle in the Wilderness

Heading into the spring of 1864, both sides knew that the killing would only increase, and the men in the ranks had learned by instinct and experience that their chances for survival improved dramatically if they could find cover—any cover—from enemy bullets. When newly appointed Union commander-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant renewed the fighting in Virginia by marching into the Wilderness on May 4, 1864, breastworks and field fortifications began to spring up every time the troops halted. Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s official reports on the fighting make numerous references to the construction of breastworks as soon as the troops had settled into a line. “My division commanders had been directed to erect breast-works immediately upon going into position,” Hancock observed. “A substantial line of breast-works was constructed of earth and logs the length of my line of battle. I directed my division commanders to entrench their lines, to slash timber in their front.” The one time a general—Confederate Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill—allowed his troops to rest rather than erect breastworks, they subsequently were routed by the enemy.

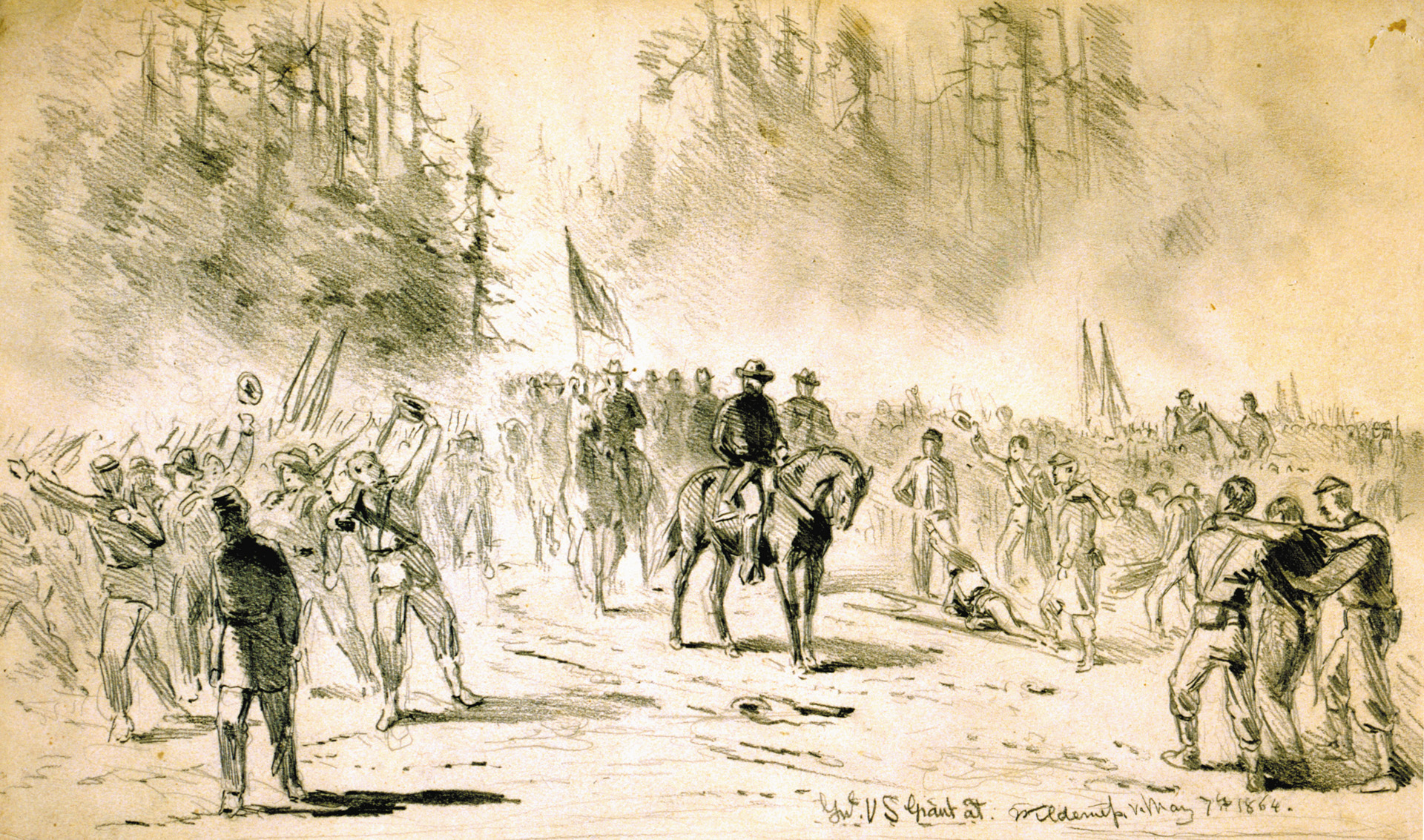

For two days, Grant slugged it out with Robert E. Lee in the primeval forest that was the Wilderness. And while Lee generally got the better of the fighting, he could mount little offensive action himself. The result was a costly stalemate, one that would not last long. Grant realized that to continue fighting in the forested abyss would negate the significant numerical advantage he enjoyed. Accordingly, he pulled out of the smoke-filled woods. Accustomed as they were to the mediocre generalship of Grant’s predecessors, such as Ambrose Burnside and “Fighting Joe” Hooker, the men in the ranks expected another dispiriting retreat. Instead, Grant headed southeast toward the critical crossroads at Spotsylvania Court House in an effort to interpose himself between Lee and Richmond. He sent word to Abraham Lincoln in Washington: “Tell the president that, whatever happens, there will be no turning back.”

Lee, too, was on the move, ordering Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson, temporarily commanding the I Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, to head for that critical junction as well. Anderson had taken over for the wounded Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, who, like Stonewall Jackson exactly one year earlier, had been accidentally shot by his own men. His snap decision not to stop during the early morning hours of May 8, as well as poor communication on the part of the Union high command, enabled the Confederate infantry to get there first. After a sharp encounter with Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s V Corps and Brig. Gen. Alfred Torbert’s cavalry division, Anderson’s advance force took possession of the vital crossroads, occupying a prominence locally known as Laurel Hill.

Other Union troops soon arrived to support Warren. Hancock’s II Corps took up positions on Warren’s right. The VI Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright in place of newly slain Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, came in on Warren’s left and pushed the Union line north through woods and fields. Farther to the east, Burnside’s IX Corps actually advanced to within a mile or two of Spotsylvania Court House itself, but halted before the Confederate trenches, leaving a two-mile-wide gap between Burnside’s right and Wright’s left.

A New Tactic to Take the Mule Shoe

Lee’s men were also moving fast, and as they arrived they stretched their lines to the north and east, entrenching all along the way. The Confederate line followed the contour of the existing high ground, and its eventual shape formed a bulging salient that became known as the Mule Shoe. To the right of Anderson’s men were Ewell’s II Corps and A.P. Hill’s III Corps, temporarily commanded by Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early. Warren’s troops furiously attacked the Rebel lines at Laurel Hill on May 8, but the graycoats could not be moved and Warren suffered terrible casualties. In between Union attacks, the Confederates did everything they could to strengthen their lines. Warren’s men, realizing this, made only half-hearted attempts the next day to resume the assault.

Despite the initial repulses, Grant continued to hammer away at the Confederate position. He recognized, however, that something else needed to be done to successfully assail the enemy entrenchments, and he was open to any new ideas. Fortunately for Grant, there was a relatively new tactic that had proven successful in limited action. Even better, he had a Union officer on hand who was thoroughly capable of leading it. This officer was New York-born, West Point-trained Colonel Emory Upton.

The new tactic involved the usual massing of troops at the point of attack. But an added wrinkle to the traditional method of assault was that while all the men would have loaded rifles, only the front rank would actually fire their weapons. During the assault, no one was to stop his forward movement to fire back at the Confederates or pause to help his wounded comrades. Rather, the entire mass of men would surge forward to the enemy works, taking whatever casualties they must, and only fire when the initial objective was gained.

Upton did not originate the tactic, but he knew that it had been effective in execution. The technique had first been used during the Chancellorsville campaign, when troops from Sedgwick’s VI Corps had broken through the Rebel lines at Marye’s Heights on May 3, 1863. Led by Brig. Gen. Hiram Burnham, the VI Corps’ Light Division, a unit made up of five tough, hard-fighting regiments and one battery of artillery, had swept up the hill and breached the very stone wall the Confederates had defended so well the previous December. Much of their success could be attributed to the willingness of the troops to sustain terrible casualties and continue to charge without stopping to reload.

Upton had seen the tactic used again the previous November when VI Corps troops routed the Confederates at Rappahannock Station, taking fortified redoubts as well as breaking through the enemy trenches. Upton knew the tactic would work—all he needed was the men to carry it out. Once Grant had approved the attack, it was left to the VI Corps chief, Horatio Wright, to pick the units Upton would lead and the point in the Confederate line that would be attacked. Wright’s chief of staff, Lt. Col. Martin McMahon, drew up a list of 12 regiments for the assault force. The units McMahon selected were the 43rd, 77th, and 121st New York; the 49th, 96th, and 119th Pennsylvania; the 5th and 6th Maine; 5th Wisconsin; and 2nd, 5th; and 6th Vermont. When shown the list, Upton remarked, “Mac, these are the best men in the army.”

“Upton’s Regulars”

Based on their collective history they may, indeed, have been the best troops in the Army of the Potomac. The 121st New York was Upton’s own old regiment, and even though he was now the brigade commander, the regiment still referred to themselves as “Upton’s Regulars.” Upton had trained and led them and knew they could fight. The 6th Maine, 5th Wisconsin, and the 43rd New York had been members of the elite Light Division. An additional benefit was that the Maine and Wisconsin regiments were familiar with the tactic of not firing when charging fixed field fortifications. The other regiments in the command all had combat experience and could be expected to perform well when muskets rattled and cannon roared.

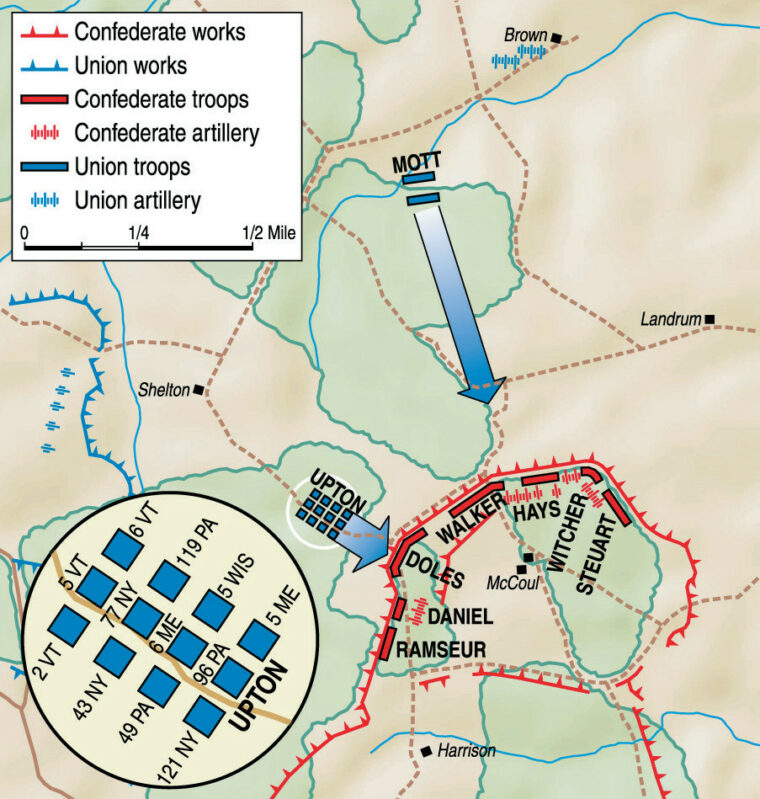

The point of attack had been determined by a captain of engineers, Ranald Mackenzie, who had scouted the Confederate position. Mackenzie found a bulge in the Confederate works on the western face of the Mule Shoe that lay about 200 yards from a forest of pine trees in front of the Union works. A wood road wound its way through the forest to a clearing directly in front of the Rebel trenches. Division commander Maj. Gen. David Russell and Upton went over the plan of attack carefully to make sure there would be no misunderstanding what was at stake. Upton would lead his regiments and force an opening in the Rebel line; he would then be supported by Brig. Gen. Gershom Mott’s brigade, which would exploit the breach.

It was a solid plan, but it had at least one fatal flaw—Mott never really understood what his role was supposed to be. His brigade had performed poorly in the Wilderness and the command was not well thought of generally. In addition, his men were posted about a mile to the left and rear of Upton’s attack, which would make his supporting role difficult to execute. Worst of all, Mott received conflicting orders from both Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade and Corps commander Wright. “Push out reconnoitering parties in all directions and obtain all possible information of the country and the enemy,” Wright ordered Mott. “The Major-General Commanding wishes you to establish connections with Burnside and Wright. If General Burnside should be pressed before 5 pm, it is believed the most efficient aid you can render him is to attack vigorously where you are.”

Mott informed Wright that his skirmishers were overextended and his force was weak. He sought further orders, noting: “My line of pickets is so extended that my troops for assault will not be more than 1,200 to 1,500 men, so that I am very weak. To call in the pickets on my left will take all the time, if not more than 5 pm. Shall I send for them?” Wright responded by ordering Mott to attack with the force he had: “I regret that your skirmish line is so extended, but if you cannot withdraw a part of the left in full time, you will not attempt to do so, but advance the whole at 5 pm as previously ordered. I rely much on the effect of your attack.”

The original plan called for the attack to commence at 5 pm. Warren’s V Corps would attack on his front at the same time to provide even greater pressure on the Confederate lines. But Warren thought he saw an opportunity to breach the Rebel lines beforehand and received Meade’s permission to attack the Confederates in his front. Warren’s men went in around 4 pm, but met with the same hail of lead and cannon fire that had stymied them the previous two days. The attack was an abysmal failure.

A Breakdown in Communication

Unfortunately, neither Grant nor Meade communicated the attack’s failure to either Mott or Upton, who at that time was gathering his troops at the Shelton House to move forward into the woods. Because of Warren’s failure, it was decided to postpone Upton’s attack until 6 pm, but no one felt it necessary to communicate this to Mott. As a result, Mott attacked as originally ordered at 5 pm. His target was the northernmost point of the Mule Shoe salient. Two things worked against Mott’s attack—his men would have to cover almost a mile of open ground before they reached the Rebel lines and, even worse, the Confederates had about 20 cannon posted in that section of the Mule Shoe.

As Mott’s men left the cover of the forest, they were hit immediately with the full fury of the Rebel cannon. The men struggled forward but were met with a hail of musketry. The result was predictable. Rather than face almost certain death, Mott’s men (mostly New Jersey regiments) broke quickly and retreated to the safety of the woods. Some troops may have gotten about 200 yards from their point of departure, but most did not even make it that far. One attacker reported, “On reaching the open field, the enemy opened his batteries, enfilading our lines and causing our men to fall back in confusion, excepting a small portion of the first line.” Another wrote, “Driving in the Rebel pickets and advancing to an open field brought us into full view of the Rebel works some 600 yards distant. Hardly had the line emerged from the wood when the enemy opened upon the column a heavy fire, whereupon the whole line broke and retreated toward our works.” As a result, Mott would be able to do nothing to support Upton’s assault.

Once again, the Union high command failed to communicate properly, and Upton had no idea that his attack would be unsupported. Ignorant of everything that had transpired earlier in the afternoon, Upton led his men, some 5,000 strong, down the wood road to the edge of the forest. Across the clearing, 200 yards away, the enemy works could plainly be seen. Earlier that day, Union pickets had driven the Confederate pickets back to their main line, and as a consequence the graycoats had little inkling of what was in store.

Upton ordered the men to lie quietly while he brought each regimental commander to the wood’s edge. There he explained what was expected of each regiment and traced the plans in the dirt so that all the commanders would know their roles. The regiments were drawn up three across and four deep. Right to left were the 121st New York, 96th Pennsylvania, and 5th Maine in the front rank; the 49th Pennsylvania, 6th Maine, and 5th Wisconsin in the second; the 43rd and 76th New York and 119th Pennsylvania in the third line; and the 2nd, 5th, and 6th Vermont in the fourth. Four of the regiments were on the right side of the wood road, while the other eight were positioned on the left.

Upton’s Advance

The plan was as simple as it was desperate. The first line was to rush and hopefully break through the Confederate breastworks. The second line was to halt at the breastworks and continue shooting forward. The third line was to stop and lie down just behind the second line while the fourth line, the men from Vermont, were to lie down and wait at the wood’s edge. After surmounting the enemy’s breastworks, the 121st New York and 96th Pennsylvania were to turn to the right and continue their attack down the Confederate line and take four artillery pieces that had been spotted, belonging to a company of the Richmond Howitzers under Captain Benjamin H. Smith. On the left, the 5th Maine was to face left and pour enfilading fire on that part of the Confederate line. Once the breach had been made, Upton expected other Union troops to exploit the gap.

The Confederates occupying that part of the line were Georgians from Brig. Gen. George Doles’ brigade. Because of their disposition, the bulge in the line was known as Doles’ Salient. The brigade consisted of the 4th, 12th, and 44th Georgia Regiments. When Ewell learned that the Confederate pickets had been driven back to the main line, he ordered Doles to reestablish the picket line “at all hazards.” Doles would not be able to comply in time.

As a result of Warren’s premature repulse, Upton’s attack was postponed until 6 pm. At 10 minutes before 6, the Union batteries of Captains Andrew Cowan, William B. Rhodes, and William H. McCartney opened up a barrage of shot and shell on Doles’ troops (one battery had already been firing intermittently for about an hour). They were to fire for 10 minutes and then cease. That was the signal for Upton to launch his assault.

The cannon opened as scheduled and pounded the Rebel works for the allotted 10 minutes, then ceased fire. When the guns fell silent, Chief of Staff McMahon waved his handkerchief. This was all Upton needed to commence his assault. When the order came, the men rose as one and stepped onto the field. Their adrenalin was pumping so fast that they forgot the order to maintain silence, and with a rousing cheer they made for the enemy. As the mass of troops double-timed toward the Rebel trenches, their officers constantly repeated the command “Forward!” Immediately, they began to receive musketry and cannon fire from the soldiers on the other side. The 5th Maine on the left, in particular, suffered greatly from the Confederate fire—so much so that they veered slightly to the right to avoid the torrent of lead.

Brutal Hand-to-Hand Fighting

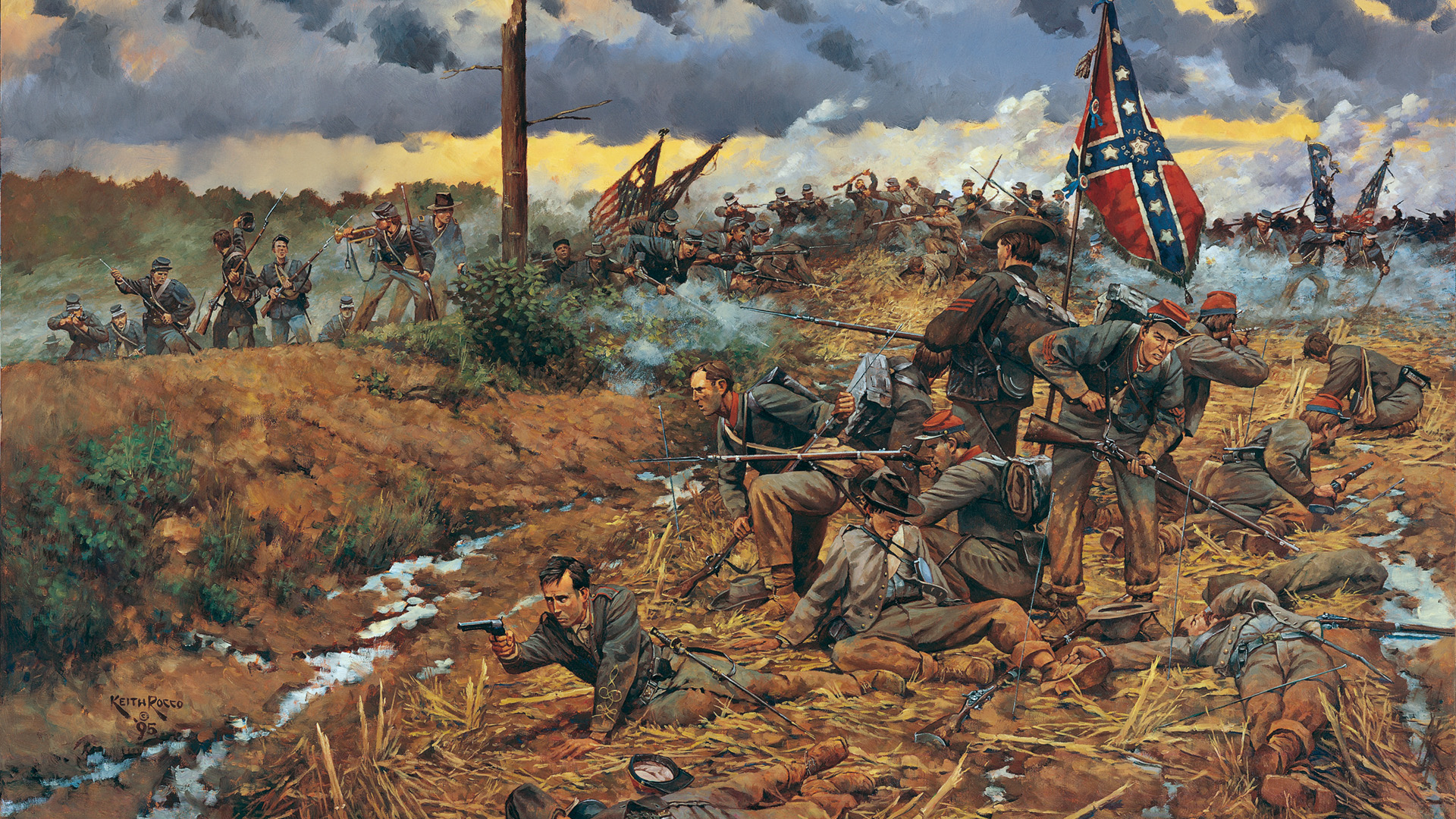

The abatis in front of the Confederate works slowed the human wave only briefly. After tearing through the impediments, the Federals reached the hated trenches. The fighting was intense and personal. The first Northerners to mount the enemy breastworks were shot through the head. Their comrades, being the combat veterans they were, did not follow their example. Rather, some held their muskets at arm’s length and fired into the crouching Confederates; others imitated New England whalers and threw their bayonet-tipped rifles into the mass of enemy on the other side.

As Upton’s men jumped into the Rebel works, deadly hand-to-hand combat ensued. One soldier in the 121st New York was bayoneted in the thigh; another from the 96th Pennsylvania was pinned to the earthwork but rescued by his comrades. A private of the 5th Maine, having bayoneted a Rebel, shot down a Confederate captain, only to fall in turn from a shot fired by a Southern lieutenant.

The men in blue would not be deterred from their mission. When the second line of Federals arrived, they poured through the enemy line. Hundreds of Confederates were captured and sent to the rear. Some of the onrushing men swept past the first line of Confederate entrenchments and made for the second line, about 100 yards in the rear. After reaching the second line, the 5th Maine faced left and unleashed an effective enfilading fire into the leftmost regiments of Brig. Gen. Thomas Walker’s Stonewall Brigade (the 2nd and 33rd Virginia). The Virginians broke and fled northward through the woods in the direction of what was then known as the West Angle, but soon would be called, more ominous and accurately, the Bloody Angle. Walker managed to rally the men and turn them around to attack the Yankees occupying their former positions.

While the Maine men were routing Walker’s Virginians, the New Yorkers and Pennsylvanians faced right and assailed the four cannon of the Richmond Howitzers. Before being captured, the cannoneers unleashed a devastating fire of canister into the densely packed blue masses. But the gunners held their fire when they saw a group of men in gray race across the field toward the Union lines. The gunners cheered what they thought was a Confederate counterattack until they noticed that the men bore no arms—they were prisoners being rushed to the Union rear. The artillerymen quickly returned to their guns, but it was too late. The delay allowed the Federal horde to sweep past Brig. Gen. Junius Daniels’ supporting North Carolinians and capture the precious pieces.

Again, Union numbers prevailed and the Confederates fled, some leaping in front of the works to make their way a short distance south to reenter their lines. The artillerists had the presence of mind to take their implements with them, denying the enemy the use of the guns. The Federals, in turn, broke off twigs in the vents in an effort to prevent any further use of the guns, should they be retaken.

A Crushing Counterattack

Upton’s attack was a wild success. It had shattered Lee’s lines and created a gaping hole half a mile wide. The road to Richmond was open—all that was needed was fresh Union troops to march through the chasm and complete the destruction of the Army of Northern Virginia. But even as Upton’s men ripped through the Rebel lines, the Confederates began reacting to the awful chasm Upton’s attack had created. On Doles’ left, the remaining men of Daniels’ North Carolina brigade bent their line perpendicular to the works and began firing at the still-advancing bluecoats. Other units rushed forward to contain the break. Ewell rode up and told Daniels’ men to hold on. “Within five minutes I will have enough men to eat up every damned one of them,” the fiery general promised. As Ewell finished speaking, the men of Brig. Gen. Cullen Battle’s Alabama brigade came racing forward to fulfill his vow.

Gradually, the Confederates were able to halt the Federals’ momentum and, as even more reinforcements arrived, start pushing them back. On Doles’ right, the rest of the Stonewall Brigade was reinforced by troops from Brig. Gen. William Witcher’s Virginia regiment. They formed a solid wall and began throwing musket fire at the 5th Maine and other Northern units. Soon, both of Upton’s flanks had been stopped cold. But the bluecoats were still far from finished. Even though Confederate reinforcements finally forced them back to Doles’ original trench line, they held on, continuing to defend the works from the outside of the trenches for another hour.

The Confederates rushed more and more reinforcements to the breach, eventually sending seven brigades to stem the breakthrough. The guns of the Richmond Howitzers were soon back in friendly hands, and the vengeful gunners turned them on Upton’s men with devastating effect. One Georgian remembered seeing Doles working the guns like an ordinary artilleryman. Ewell seemed to be everywhere, rushing brigade after brigade forward to repel the attackers. Robert E. Lee even threatened to join in the fray. He had been at the Harrison House when Upton’s assault started, and as he began to see the extent of the break he rode forward, giving his troops the impression that he intended to lead a counterattack. But, as had happened a week earlier in the Wilderness, Lee’s aides and other troops implored the general to go back. Once he was assured that the breach in his lines would be sealed, Lee rode away.

A Bitter Withdrawal

An aide was sent to the eastern portion of the Mule Shoe to brief Brig. Gen. George H. Steuart on the situation and tell him his men were needed to push back the Yankees. Steuart protested that if he left his section of the line, he could be attacked himself. The aide finally persuaded Steuart to move, and the general ordered his men to about-face and double-time to the other side of the salient. Meanwhile, the men of the 60th Georgia, part of a brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. John B. Gordon, arrived on the field. They deployed at the front and prepared make the final assault to push the Yankees into retreat.

Seeing that more and more Confederate reinforcements were arriving by the minute, Upton rode back to the woods to get the Vermont men to counter the enemy advance. When he got to the woods, Upton learned that the Vermonters had already gone forward without orders, unable to keep themselves from the battle. They had gone in on the left and were doing considerable damage to the Virginians of the Stonewall Brigade and the other Confederates who reinforced them. But Upton knew that without additional support he could accomplish nothing further. That support was not coming and it was growing dark, so Upton went to Russell and requested permission to withdraw. Russell immediately approved. The word went out and the men in blue hastened back to the protective cover of the pine trees. Some of the Maine and Vermont men at first refused to give up the ground they had won, remaining behind for several more minutes and continuing to hold off the Confederates. But when a second, more forceful command came from Wright to withdraw, they grudgingly complied.

“Gallant and Distinguished Services”

When the men had finally returned to the safety of the pine woods, many wept openly at what had transpired, disgusted that such a fine opportunity to crush the Army of Northern Virginia had been thrown away. Many blamed Mott for his failure to come to their support, but the real blame for the failure lay with Wright, Meade and, ultimately, Grant himself. Poor communication and lack of coordination had doomed Upton’s attack even before the men stepped out of the woods. Despite the failure, Upton received his general’s stars the next day as he had been promised. He was understandably pleased with the promotion, noting, “I was promoted for gallant and distinguished services.”

Several lessons were learned as a consequence of Upton’s assault. The tactic of massing men at a single point and having them charge without stopping to fire had worked even better than expected. Grant took the lesson to heart and decided that what 12 regiments could do an entire corps could do even better. He would try again two days later. But what Grant had failed to learn from Upton’s attack was that communication and coordination were absolutely essential for any such attack to succeed entirely. His failure to grasp the meaning of Upton’s attack led to an even greater effort two days later that would also fail with an even more horrendous cost in lives and blood. Rather than being a harbinger of success, Upton’s assault on the Mule Shoe was merely the prelude to an even greater slaughter at the “Bloody Angle.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments