By Mike Mclaughlin

On the morning of December 31, 1941, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz assumed command of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. The service took place at the submarine base at Pearl Harbor. The mood was grim. More than two thousand men had been killed in the Japanese attack on December 7. The Battleship Force had been wrecked, and most of the Army and Navy’s planes were destroyed on the ground.

The fleet commander had been Admiral Husband E. Kimmel. The Navy replaced him, temporarily, with Admiral William Pye.

Fearing further damage to the fleet, Pye canceled a mission to rescue the besieged Marines on Wake Island. When Nimitz replaced Pye, morale was so low he worried if it could ever be raised. Every officer present feared blame for the disaster, and reassignment to God only knew where. Yet Nimitz’s previous command was the Navy’s Bureau of Navigation, which kept the records of the men at Pearl. He knew what they were capable of, and he set out to restore their faith. He needed it. When he was chosen, President Roosevelt had said, “Tell Nimitz to get the hell out to Pearl and stay there until the war is won.”

Commander Edwin Thomas Layton was the Fleet Intelligence Officer. His colleagues had regarded him as alarmist. He had been convinced the Japanese would attack the oil-rich Dutch East Indies and then, to protect the left flank of their sea lanes, would also strike the U.S. forces in the Philippines. This they did, hours after bombing Pearl. Later that day, one officer said, “Here’s the man we should have listened to all along.”

Layton assumed his intelligence career was finished and requested command of a destroyer. Nimitz had good reasons to disagree. Layton had been Assistant Naval Attaché in Japan, and he spoke excellent Japanese. He knew the Japanese Navy’s chief strategist, Admiral Iso- roku Yamamoto, and the leader of the Pearl Harbor attack, Admiral Chuichi Nagumo.

“I want you to be the Admiral Nagumo of my staff,” Nimitz told him. “I want your every thought, every instinct as you believe Nagumo might have them. You are to see the war, their operations, their aims, from the Japanese viewpoint and keep me advised what you are thinking about, what you are doing, and what purpose, what strategy, motivates your operations. If you can do this, you will give me the kind of information needed to win this war.” Layton took the challenge. He later wrote, “I was not so sure about his conclusion. But my respect for his enthusiasm and determination to restore the reputation of the fleet was fired up.”

Born in 1903 in Nauvoo, Ill., Layton had a lifelong ambition: a career at sea. Battleships and the U.S. Naval Academy were his favorite writing subjects in high school. He applied to Annapolis in 1920 and was accepted.

The Naval Academy stressed navigation, gunnery, and tactics used during World War I. Radio interception and code-breaking were off the path to flag rank. Despite this, Layton was fascinated by codes and ciphers and saw their value in naval strategy.

In January 1924 the Office of Naval Communication (ONC) established a cryptographic research department in Washington, DC. Headed by Lieutenant Laurence Safford, the unit consisted of himself, two analysts, and a typist. As Safford set up shop, Edwin Layton was finishing his last year at Annapolis.

Upon graduating, he was assigned to the battleship West Virginia. In January 1925 the West Virginia sailed to San Francisco to join a ceremony for Japan’s naval cadet training squadron. Layton met his counterparts from the naval school at Etajima. They were amiable, enthusiastic men who spoke fluent English or French. Not one U.S. officer could speak Japanese.

Layton urged the Navy to start a Japanese language program. He learned that such a program existed, and that only two officers a year were accepted. Layton applied and waited. After five more years of battleship and destroyer duty, he was accepted.

En route to Japan in 1929, he met Lieutenant (j.g.) Joseph Rochefort. Rochefort had worked with Safford at the ONC crypto unit, now called OP-20-G. Layton and Rochefort became good friends. Their friendship would be invaluable in the years ahead.

In Tokyo, Layton received a no-nonsense briefing from the naval attaché. “You have only two duties to perform: One, study and master the Japanese language. Two, stay out of trouble. If you fail in either, I’ll send you home on the next ship.”

Layton’s instructors stressed basics that Japanese children already knew by their first day of school. He had to learn the sounds of the language, and then the grammar and vocabulary. Then he began transcribing Japanese newspapers into English. He attended plays and operas. “Revenge is the central theme of our drama,” one teacher told him. “Never forget that.” He studied Japan’s national character and learned the depth of their outrage when the United States barred Japanese immigration in 1924. The insult was double-edged because it also placed them in the same category as Koreans, Chinese, Indonesians, and Indians. “Always remember,” his teacher said, “that in the Japanese mind we are a superior race.”

In June 1936 Layton transferred to Washington as the new head of the translation section OP-20-GZ. Through his work there, he learned that the Japanese Navy was refurbishing one of its older battleships, the Nagato, and that her rebuilt turbines could reach 26 knots. The U.S. Navy had believed she could only reach 23 1/2 knots, and with that in mind had planned the new North Carolina class of battleships. Layton’s discovery prompted the Navy to improve the class so it could exceed 28 knots. Afterward, Safford declared, “This paid for our peacetime radio intelligence organization a thousand times over.”

After two more years in Japan as assistant naval attaché, Layton took command of the destroyer Boggs in 1939. That summer, he ran across an old friend, Captain Ellis Zacharias, the intelligence chief for the Eleventh Naval District (San Diego). Over drinks, he asked, “How would you like to be fleet intelligence officer?” Layton was surprised, yet interested. Thinking about it later, he wrote, “Whoever got the job would be the busiest man on the staff when the inevitable conflict broke out.”

By 1941, Commander Safford’s research department had become the Security Intelligence wing of the ONC. It had three stations: Negat (Washington), Cast (the Philippines), and Hypo (Pearl Harbor). By then, hundreds of men and women, military and civilian, were applying themselves to deciphering Japanese messages.

Japan’s diplomatic code was nicknamed “Purple.” There were several versions of the military code, beginning with “Red” in the 1920s, then “Blue.” By 1941, the Japanese naval code was JN-25. It was composed of tens of thousands of five-digit numbers. Each number represented a ship, unit, person, or place. All messages included a fixed value that was added to each code number. With it was an instruction for the receiver to use a particular number to subtract from each number in order to decipher the message.

The codes were periodically changed. Decryption required both intuition and a memory for countless details. Some changes were subtle. Other, more complex changes took thousands of man-hours to evaluate. Success was never total.

Opportunities came in different ways. One happened in 1920. An Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) team broke into the New York office of the Japanese vice-consul, who was a naval officer. They cracked his safe and photographed his code book. The photos were transcribed into a red, leatherbound book. This became the Red code book, a keystone for the ONC’s analysis.

Layton became Fleet Intelligence Officer in December 1940. He worked for Admiral James O. Richardson, and then his successor, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel. Layton gave daily briefings on Japanese military activity throughout the Pacific. This reunited him with Station Hypo’s boss, his old friend Commander Joseph Rochefort.

Washington frequently disagreed with Pearl. Admiral Stark, the Chief of Naval Operations, often doubted if the Japanese would make any aggressive moves at all. The Atlantic was consuming Washington’s attention because German U-boats were savaging Allied merchant shipping.

In June 1941, Negat (the Washington station) accused Hypo (the Pearl Harbor station) of withholding information regarding a Japanese buildup in its Mandated Islands, Pacific Islands transferred to Japanese control after World War I. Stunned, Layton pointed out that the information came from Station Cast (the Philippines) and had been sent to Negat, with a copy to Hypo; a Negat officer simply hadn’t appreciated the message’s significance. The incident illustrated OP-20-G’s decentralized structure. Six months later, the structure would be shown to be tragically flawed.

Hypo saw only Japanese naval messages. Lacking Purple decryption equipment to read diplomatic traffic, they depended on Negat for that information. Hypo’s problems grew worse when JN-25 was changed for the second time that year, on December 1.

By late November, Negat believed that Admiral Nagumo’s carriers were operating in the western Pacific, with some cruising to Indochina. But Nagumo was already heading east to Pearl, under radio silence so enforced that the transmitter keys had been removed from his ships’ radios.

When Nimitz took command, he wasn’t impressed with Hypo. If they were so good, why didn’t they foresee the attack? It was an agonizing question that reverberated through the Navy for years. It triggered many investigations, caused endless finger-pointing, and permanently stained Kimmel’s reputation. Layton stressed that if the Japanese had broadcast anything about the attack, they used a code he knew nothing about. Nimitz came around.

Every day, Layton and Rochefort laid out dozens of intercepts on plywood tables. Each message listed the sender and the recipient. It was a puzzle with many missing pieces, but enough fit to give an idea of the picture. An Allied base mentioned with weather reports and increased Japanese air patrols often pointed to an impending attack.

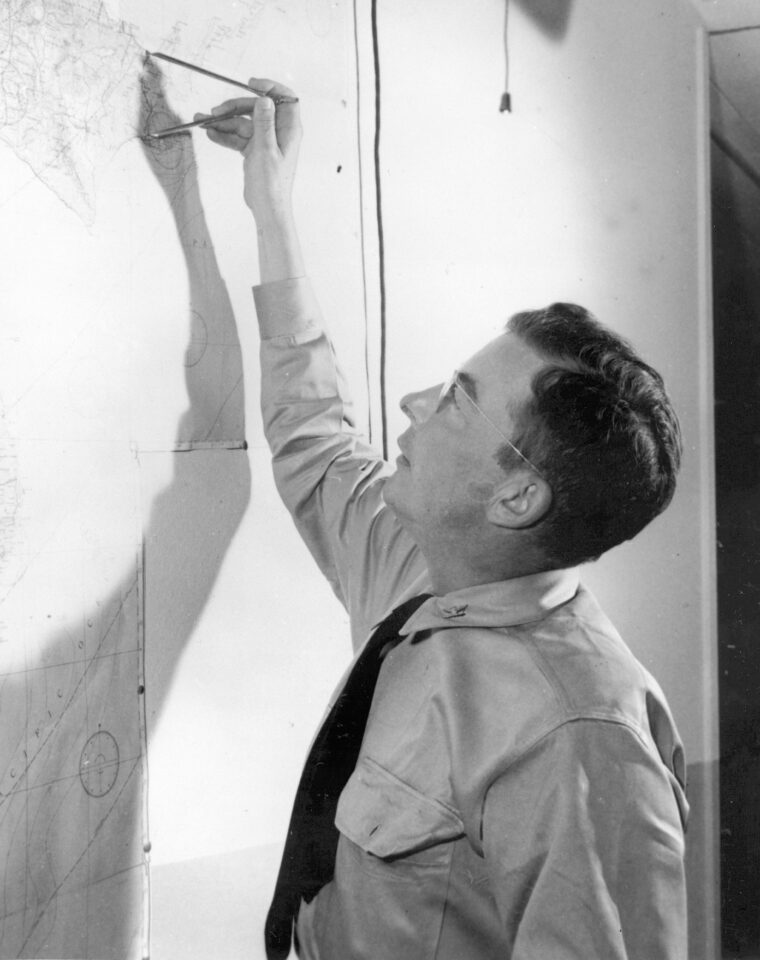

In the weeks that followed the travesty of December 7, Layton briefed Nimitz every morning at 8 am. If vital information came in, Nimitz’s door was always open to him. The Commander-in-Chief Pacific (CincPac) Operations room had a huge map of the Pacific, with tracing paper laid over it. Every night, Layton’s men wrote on it the latest information about Japanese units.

Through the winter and spring, Nimitz sent his carriers to raid the Marshall and Gilbert Islands. While these raids didn’t slow the Japanese conquest of the Dutch East Indies and the Philippines, they did much to boost morale for the United States. So did the Doolittle raid on Japan in April 1942. The raids also alarmed the Japanese high command.

ONC suffered a shakeup in February 1942. The Navy’s commander-in-chief, Admiral Ernest J. King, dismissed Negat’s long-time commander, Laurence Safford. It was part of a plan for better administration, but slashed a vital personal link between Hypo and Negat.

Admiral King was also the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Nimitz worried about King’s “Europe first” view. Washington, over five thousand miles to the east, saw the Japanese threat in a different light. Nimitz recalled the Texas saying, “The nearest rattlesnake is always the biggest.” He valued Hypo’s work over Negat’s. He told Layton and Rochefort, “Tell me what the Japanese are going to do, and I will then decide if it’s good or bad, and act accordingly.”

By late April 1942, Layton was convinced that the next Japanese target was the Allied base at Port Moresby, New Guinea. Nimitz agreed, and sent Admirals Aubrey Fitch and Frank Jack Fletcher with the carriers Lexington and Yorktown to counter the threat.

The Battle of Coral Sea followed, from May 4 to May 8. By the 8th, U.S. planes had sunk the light carrier Shoho and damaged the heavy carrier Shokaku. The carrier Zuikaku came through unhurt but lost many of its planes. The Japanese struck back, sinking Lexington and damaging Yorktown. Despite this, the Japanese fleet retreated north, canceling the invasion.

Soon another invasion—“MI”—was in the works. Layton and Rochefort had come across a recurring designator, “AF.” Japanese patrol planes used two-letter designators beginning with “A” when discussing the Hawaiian Island chain. When Rochefort learned that Japanese planes were advised to avoid AF’s fighter cover, he came to believe that AF was Midway. Washington felt that the next attack would be elsewhere. Rochefort devised a simple trick to settle the question. Layton pitched it to Nimitz. Nimitz approved.

Using their underwater cable between islands, Pearl Harbor ordered Midway to radio-transmit in plain language that its fresh water condenser was broken. The Midway station did so. The Japanese station at Kwajalein intercepted it, then reported: “AF needs fresh water.” That settled it. Midway was the target. Even Washington came around. The break happened just in time. The JN-25 code was changed again, and it would be weeks before Hypo could evaluate the changes.

The miraculous victory occurred a week later. Nagumo’s carriers approached northwest of Midway, just as Hypo said they would. American dive-bombers attacked, flying from Admiral Raymond Spruance’s Enterprise and Hornet and from Fletcher’s Yorktown. All of Nagumo’s carriers were sunk. Again, the American cost was high, too. Yorktown and the destroyer Hammann were sunk, and hundreds of Navy and Marine airmen were killed. But once more, Nimitz’s men stopped an invasion.

Layton contributed to the victory in another way. In March, Japanese seaplanes flew scouting missions over Oahu. When one dropped bombs near Pearl, Nimitz asked how it was possible. Layton recalled an article called “Rendezvous,” written by a friend of his, which described how a PBY Catalina was refueled by a submarine at a remote atoll. Layton figured the Japanese had done just that at French Frigate Shoals. Nimitz sent ships to guard the shoals. As a result, the Japanese canceled a reconnaissance mission. Nagumo steamed to Midway without knowing where the U.S. carriers were.

After Midway, the Japanese Navy lost the offensive. Despite this, Nimitz had limited resources to fight with. He would get new carriers, battleships, and more in 1943, but until then, he had to make do. The desperate fight for Guadalcanal consumed his energies for the rest of the year.

That autumn of 1942, Hypo took a hard blow. Negat had long viewed Hypo as a rogue outfit. Rochefort, who had loudly disdained Negat’s work, was ordered to report to Washington for “temporary” consulting work. “I’m not coming back,” Rochefort told Layton. He was right.

In early November, Admiral King wrote to Nimitz, “Now that I have taken care of Rochefort, I will leave it up to you to take care of Layton.” Nimitz showed Layton this dark note. “You’ve got an enemy there,” Nimitz said. Layton wondered again if he should return to commanding a destroyer.

But he did not. Over the next two years, CincPac’s intelligence staff expanded to nearly 50 times its original size. At first, Nimitz was opposed to this. He liked small outfits, straight lines of contact, and no red tape. But with the ongoing campaigns stretching toward Japan, Layton needed a larger department. Thus, his handful of men expanded to nearly 2,000 by the war’s end. Marine, Coast Guard, and Army intelligence men worked with the Navy. They composed the Joint Intelligence Command Pacific Ocean Area (JICPOA).

Layton studied enemy logistics. Japanese unit commanders sent housekeeping reports about the amount of rations consumed in a month and the number of men fit for duty. Reading this helped the Marines and Army understand what they would face when they went ashore. During invasions, JICPOA men seized documents and interrogated prisoners to assess enemy defenses. JICPOA also tracked Japanese merchant convoys and relayed the information to U.S. subs, which began sinking Japanese transports in increasing numbers.

Layton read one particularly powerful intercept on April 14, 1943. It was the travel itinerary for an inspection trip by Admiral Yamamoto. Nimitz stared hard at it, then looked at his map. Yamamoto would be within range of fighters from Guadalcanal. Nimitz asked, “Do we try to get him?”

During his time in Japan, Layton had known Yamamoto. Within the limits of duty, Layton considered him a friend. But that was six years earlier. “Yes,” Layton answered. “We should. He’s unique among their people. If he’s shot down, it would demoralize the navy. It would stun the nation.” Nimitz replied, “What concerns me is whether they could find a more effective fleet commander.” The two men discussed the senior commanders of the Japanese Navy. Finally, Layton said, “You know, Admiral, it would be just as if they shot you down. There isn’t anybody to replace you.” Nimitz smiled. “All right. We’ll try it.”

On April 18, 1943, Army P-38 fighters shot down Yamamoto’s plane. Japan’s greatest military mind was killed.

Through the war, Layton often had to challenge the claims of men who’d been closer to the action. In July 1943 he incurred the wrath of Admiral Walden Ainsworth, who’d reported that his forces had sunk two enemy cruisers in a night battle. Layton denied it. Ainsworth flew to Pearl to report to Nimitz, and to shake his finger in Layton’s face. “How can you sit here on your fat ass, thousands of miles from the action, and make such a statement!” Layton replied that his mission was to evaluate enemy radio traffic. No enemy cruisers had been reported lost. “I have no stake in this matter personally,” Layton said. “But I have a stake in the war.” Later, he was vindicated when a captured Japanese sailor confirmed his analysis. It had been unpleasant, but Nimitz needed hard facts. Layton was a man who could keep his head and report bad news as well as good.

Two years of bitter fighting remained. With every invasion, the ferocity of resistance increased. Surrenders were few. Kamikaze attacks at Iwo Jima and Okinawa inflicted massive casualties on U.S. ships.

When briefed on the Manhattan Project, Layton believed it offered Emperor Hirohito a face-saving way to end the war. To his way of thinking, nothing less would work. That supposition has been debated ever since. But the Japanese did come to terms directly after the atomic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On August 15, Layton received the Japanese message accepting the terms of surrender. He raced it to Nimitz, who held up a similar sheet and said, “I just got one from Admiral King.” The next day, Nimitz put the word out: “Suspend all operations.”

Nimitz invited Layton to accompany him on a visit to Yokosuka Naval Base. “You’d better bring a Marine,” Layton warned him.

“They wouldn’t attack me,” Nimitz said, surprised.“They’d attack MacArthur.” Layton disagreed. “They know it was our naval power that brought them to their knees.”

“Are you a good shot?” Nimitz asked. Together they drove to Nimitz’s personal shooting range and practiced for several days. When they went to Yokosuka, Layton didn’t need the pistol. Their visit was a quiet one.

On September 2, Layton watched his boss sign the Japanese surrender on the deck of the Missouri. They had crossed half the world and four years to reach this moment. And while the Pacific War produced many great admirals and generals—Halsey, Spruance, Fletcher, Mitscher, Burke, Vandegrift, Smith, and more—one man alone, Chester W. Nimitz, was responsible for them. To make sound decisions when giving orders to these men, Nimitz needed solid information. Layton gave it to him.

For this, Layton won a Distinguished Service Medal, plus many other decorations. But none of them matched what Nimitz gave him, in the fall of 1942, when Layton’s worries were grave. Nimitz had taken a photo of himself from his desk and signed it. “To Commander Edwin T. Layton,” he wrote. “As my intelligence officer, you are more valuable to me than any division of cruisers.”

Mike McLaughlin is a freelance writer and military historian. His work has been published by AMVETS magazine, American Veteran and The Boston Tab newspaper. He lives with his wife, Geralyn, in Winthrop, Massachusetts.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments