By Roy Morris, Jr.

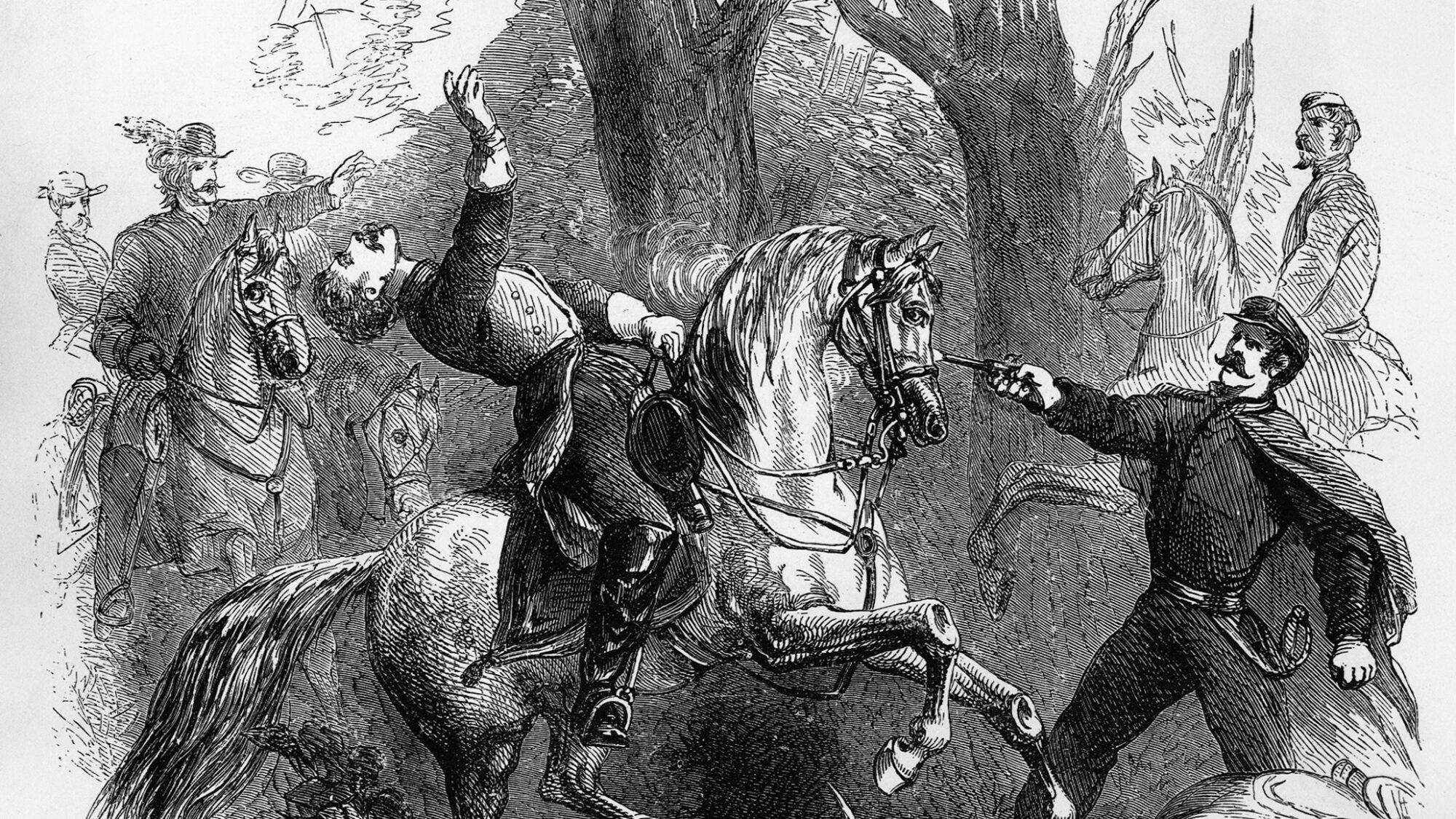

Although undeniably brave and noble, Union General Robert McCook’s parting comments as he lay dying of a gunshot wound in a stranger’s bed in south-central Tennessee did not achieve the immortality of other famous last words by Civil War generals. “I am done with life,” McCook reportedly told a comrade. “Yes, this ends it all. You and I part now, but the loss of ten thousand such lives as yours and mine would be nothing if their sacrifice would but save such a government as ours.”

McCook’s last words, suspiciously grandil- oquent and self-abnegating for a man shot in the bowels, could not match the homespun poetry of Confederate general Stonewall Jack- son’s legendary farewell. Jackson, himself dying of the effects of a gunshot wound suf- fered at the Battle of Chancellorsville, roused himself to mutter poetically, “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.” Despite being based on a rather humble child- hood memory of coming home one night from a long day of drudgery in a sawmill, Jackson’s vaguely biblical words entered the national lexicon as a timeless expression of peace, acceptance, and resignation. Modern writer Ernest Hemingway appropriated the quote as the title for one of his worst novels, Across the River and Into the Trees. One wishes it had been put to better use.

Civil War-era society had a morbid if understandable fascination with death, and it was not uncommon for a dying man’s friends and relatives to cluster about his deathbed to record his last earthly statement. Such words, it was believed, were messages from the great beyond. The mystical nature of such messages did not always deter listeners from improving upon or even inventing entirely more suitable parting words. Such was the case of Jackson’s old commander, Robert E. Lee.

Ignoring the Testimony of Lee’s Relatives

After suffering a debilitating stroke in Sep- tember 1870, Lee lingered near death for nearly two weeks at his family home in Lex- ington, Virginia. Family members attended every groan and sigh from the great general, listening in vain for a last memorable pro- nouncement. Lee’s condition did not permit coherent speech. Biographer Emory Thomas notes that Lee spoke an average of one word per day during the last 12 days of his life. Lee, says Thomas, “may have lived an exemplary life, but he was certainly doing a poor job of dying.” Finally, on the last day, the general murmured inscrutably, “I will give that sum.” No one knew what he was talking about.

Lee idolator Douglas Southall Freeman, ignoring the direct testimony of Lee’s relatives, attending physicians and friends, came up with a more suitable leave-taking for the Confederate icon. In Freeman’s version, Lee alternated between pious prayers and crisp, com- manding orders such as, “Tell [A.P.] Hill he must come up.” According to Freeman, Lee’s last words were the simple and majestic “Strike the tent,” after which he expired as conveniently and dramatically as the wispy heroine in a Victorian-era melodrama. As the hero in another Hemingway novel says sardonically, “Isn’t it pretty to think so?”

Another Civil War general’s famous last words were not invented outright, but they were subtly changed for comic purposes. On May 9, 1864, Union Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick was overseeing his troops prior to the Battle of Spotsylvania. Sedgwick became annoyed by what he considered his men’s excessive bobbing and weaving in the face of enemy fire. “They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance,” Sedgwick grumbled to his staff. A few minutes later, a bullet crashed into Sedg- wick’s face below the left eye, simultaneously contradicting his recent statement and ending his life. Ever since, jokesters have shortened the general’s prosaic last words to the more gruesomely comic, “They couldn’t hit an ele- phant at this dist—.” Such, perhaps, is the price of fame.

Originally Published May 26, 2014

I suspect last words could be a glance at common humanity.