By Al Hemingway

It is ironic that President Andrew Jackson, who was a staunch pro-Union advocate, actually bolstered states’ rights supporters when he refused to endorse the 1832 Supreme Court decision against the State of Georgia in the forced relocation of Native Americans from their homes after gold was discovered on their land. The court said that it was illegal for Georgia to impose its laws in the Cherokee nation; only the federal government had authorization to do so. Infuriated with the court’s ruling—and with Chief Justice John Marshall—Jackson reportedly said, “John Marshall has made his decision. Let him enforce it if he can.”

Jackson, of course, knew that Marshall did not have the U.S. Army at his disposal. In the end, the Cherokee were made to leave their land, often at the point of a bayonet, and relocate to Indian Territory in modern-day Oklahoma. The long, arduous trek would later become infamous as the “Trail of Tears.” More importantly, “Old Hickory’s” actions had long-term ramifications for Congress, the states’ rights movement, and Native Americans themselves. It was a dispute that festered for years until the Civil War erupted in 1861.

In his new book, Driven West: Andrew Jackson’s Trail of Tears to the Civil War (Simon & Schuster, New York, 2010, 480 pp., index, notes, photos, $30.00, hardcover), veteran historian A.J. Langguth vividly describes the events that transpired during that tumultuous period of our nation’s history, a period of four decades that still remains an embarrassment to this day.

Langguth traces the pivotal figures in the actions leading up to the 1838 removal of the Five Civilized Tribes, focusing primarily on the Cherokee. The Native Americans sent delegations to Washington to meet with Jackson and his cabinet to hammer out a proposal that would benefit all parties involved. When a decision was finally reached, even though the Cherokee were to be compensated for their land, it created a schism within the tribal leadership that eventually led to several members of the commission being assassinated because they had violated the “Blood Law,” which prohibits any Cherokee from selling land without tribal permission.

Although Jackson signed the bill into law, it was his crafty successor, President Martin Van Buren, who had the legislation put into force. General Winfield Scott and the Army herded thousands of Cherokee into camps, while their homes were destroyed and their personal property was confiscated. With little food and scant clothing to protect them against the harsh winter conditions, the Cherokee began a 1,000-mile march to Indian Territory. By the time they had reached their final destination, an estimated 4,000 tribesmen had perished on the horrific journey.

Although Jackson signed the bill into law, it was his crafty successor, President Martin Van Buren, who had the legislation put into force. General Winfield Scott and the Army herded thousands of Cherokee into camps, while their homes were destroyed and their personal property was confiscated. With little food and scant clothing to protect them against the harsh winter conditions, the Cherokee began a 1,000-mile march to Indian Territory. By the time they had reached their final destination, an estimated 4,000 tribesmen had perished on the horrific journey.

Langguth includes accounts from individuals describing atrocities committed by some of the soldiers guarding the Indians, as well as white settlers they encountered along the way. Some residents in Golconda, Illinois, charged the Cherokee $1 a head to cross the river, when the going rate was 12 cents. A few Indians were slain during the disagreement, and later the residents sued the federal government for $35 for each Cherokee they buried after killing them.

Even after the Cherokees reached their destination, the feud between the tribal leaders continued. The followers of John Ross were pitted against Stand Watie’s faction until the federal government arranged a fragile treaty in 1846 to stop the bloodshed. When Civil War broke out, the two sides split once again. Ross’s men sided with the Union, while Watie’s supporters stood with the Confederacy. Watie would distinguish himself in battle and later be appointed a brigadier general, the last Confederate general to surrender at the end of the conflict.

Many Cherokee who had befriended Jackson during the Creek Wars were bitter toward their former commander. One chief, Junaluska, who had fought alongside Jakcson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in March 1814, probably best summed up the Cherokees’ feelings when he remarked, “If I had known that Jackson would have driven us from our homes, I would have killed him that day at the Horseshoe.”

Although the United States government formally apologized to the Cherokee Nation in 2009, more than 170 years after the “Trail of Tears,” the apology included a disclaimer that disallowed any monetary award for their suffering.

Sacred Ties: From West Point Brothers to Battlefield Rivals: A True Story of the Civil War by Tom Carhart, Berkley Books, New York, 2010, 374 pp., index, notes, $25.95, hardcover.

Sacred Ties: From West Point Brothers to Battlefield Rivals: A True Story of the Civil War by Tom Carhart, Berkley Books, New York, 2010, 374 pp., index, notes, $25.95, hardcover.

The United States Military Academy at West Point, the gray-stone bastion on the banks of the Hudson River in New York, has become synonymous with duty, honor, and country since it first opened its doors in 1802. Nowhere was the call to duty more evident than during the Civil War. During the conflict, 328 West Pointers were generals in the Union Army, while 164 wore stars on their collars for the South. Many of the graduates led corps, brigades, and divisions on both sides of the conflict.

To demonstrate the strong bond between individuals who attended the Academy, Carhart has selected six men who went on to distinguish themselves during the Civil War: Henry Algernon DuPont, George Armstrong Custer, and Wesley Merritt, who wore Yankee blue, and John Pelham, Thomas Lafayette Rosser, and Stephen Dodson Ramseur, who donned Rebel gray. These half-dozen soldiers were a microcosm of the cadet population of West Point. The men became lifelong friends despite their political beliefs, and proved themselves to each other by their actions on the field of battle.

Carhart’s book traces each individual from his time at the Academy, during the war, and his endeavors after the shooting had stopped. Two of the number, Pelham and Ramseur, were killed during the conflict. Ramseur’s death at Cedar Creek was particularly tragic because he had been captured by Union forces, and Merritt and Custer endured emotional reunions with their former classmate on his deathbed.

DuPont, Rosser, and Merritt went on to lead productive lives after the war. Everyone, of course, knows what became of the boy-general. Custer and his men were massacred at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in June 1876. Ironically, it was Merritt who presided over the court of inquiry that investigated Custer’s death. Merritt later was promoted to major general and went to the Philippines as military governor. While Ramseur was mortally wounded at Cedar Creek, DuPont would receive the Medal of Honor for his actions during the fighting there. He later went on to a distinguished career in politics and as president of a railroad. Rosser also enjoyed success as a railroad engineer after the war. He was later appointed brigadier general of volunteers by President William McKinley, also a Civil War veteran, and trained troops during the “splendid little war” in 1898.

Whatever their accomplishments or misgivings, each individual was imbued with a sense of brotherhood first attained while attending West Point. That tradition remains firm today with the cadets who man the “Long Gray Line.” Only death can end their attachment to West Point—and each other.

Predator: The Remote-Control Air War Over Iraq and Afghanistan: A Pilot’s Story by Matt J. Martin and Charles Sasser, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 310 pp., photos, $28.00, hardcover.

Predator: The Remote-Control Air War Over Iraq and Afghanistan: A Pilot’s Story by Matt J. Martin and Charles Sasser, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 310 pp., photos, $28.00, hardcover.

Be prepared to mentally strap yourself into the pilot’s seat while reading this book. The author takes the reader through the streets of Balad, Baghdad, and other trouble areas of Iraq during his tour of duty. There is, however, one major difference. Martin himself was not actually seated in the plane, but flying it remotely, sometimes from as far away as Nellis Air Force base in Nevada.

Martin was among the first group of pilots to train on the MQ-1 Predator, a remotely piloted aircraft (RPA). He “flew” hundreds of missions and supervised thousands more, hunting down insurgents who were setting up ambushes and firing mortars and rockets at American troops. In this surreal world, Martin could fly his RPA armed with missiles virtually unnoticed, swooping down from the skies, targeting terrorists or al Qaeda leaders and, once given the clearance, eliminate them. “Sometimes,” he wrote, “I felt like God hurling thunderbolts from afar.”

As its popularity grew, the demand for RPAs increased. Field commanders recognized the significance of the unmanned aircraft, which could provide valuable reconnaissance data and, more importantly, save American lives by eliminating threats before they occurred. Newer models of the RPA are now in service in Afghanistan, although their specifications are still top-secret. Their presence in this and future wars will be a reassuring factor to the troops on the ground, who will know that an “eye in the sky” is constantly on patrol to safeguard them.

Between War and Peace: How America Ends Its Wars edited by Colonel Matthew Moten, Free Press, New York, 2011, 320 pp., notes, $27.99, hardcover.

Between War and Peace: How America Ends Its Wars edited by Colonel Matthew Moten, Free Press, New York, 2011, 320 pp., notes, $27.99, hardcover.

Here is a most timely book that, as the editor writes, should be read by future presidents before they decide to bring this country into a war. Fourteen renowned historians have written short essays on different wars that the United States has been involved in, beginning with the American Revolution. The question was asked, “How has the United States ended its wars, and how well has it accomplished its political aims and strategic goals in the past?” It is certainly an intriguing query.

The majority of conflicts that America has participated in have been a two-edged sword. While most were won on the battlefield by military actions, the political, social, and economic ramifications were often overlooked, most recently by the Bush administration’s obtuse Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld. Some American wars spurred inflation, unemployment, and widespread unrest after they were over.

This account could not have emerged at a more appropriate time. Recently, the war in Afghanistan has become America’s longest conflict, with no end in sight. The previous administration brought the United States into the conflict with no clear strategy on the method to be used to win the war. The same flawed mentality happened more than four decades ago in Vietnam, and sadly continues today.

The Crisis of Rome: The Jugurthine and Northern Wars and the Rise of Marius by Gareth C. Sampson, Pen & Sword, South Yorkshire, Great Britain, 2010 192 pp., notes, index, illustrations, $39.95, hardcover.

The Crisis of Rome: The Jugurthine and Northern Wars and the Rise of Marius by Gareth C. Sampson, Pen & Sword, South Yorkshire, Great Britain, 2010 192 pp., notes, index, illustrations, $39.95, hardcover.

There is no doubt that Gaius Marius was a very heroic soldier, consummate politician, and brilliant strategist. The Roman statesman has been credited with instituting massive military reforms, allowing the Roman Army to become the mighty force that ruled the ancient world for centuries.

Noted historian Gareth C. Sampson questions the fact the Marius created the army that was destined to claim numerous victories on the battlefield. He claims that there is no evidence that Marius was instrumental in restructuring the army and creating the cohort. Sampson states that such advances had already taken place and the revamping of the Roman army was “evolution rather than revolution.”

The author does credit Marius’s victories against the northern tribes to his enthusiastic training regimen and his focus on small-scale warfare. Marius knew how the tribes conducted themselves in battle, and he taught his men this more personalized style of fighting. This is an intriguing account of the military life of one Rome’s greatest warriors—but maybe not one of its greatest generals.

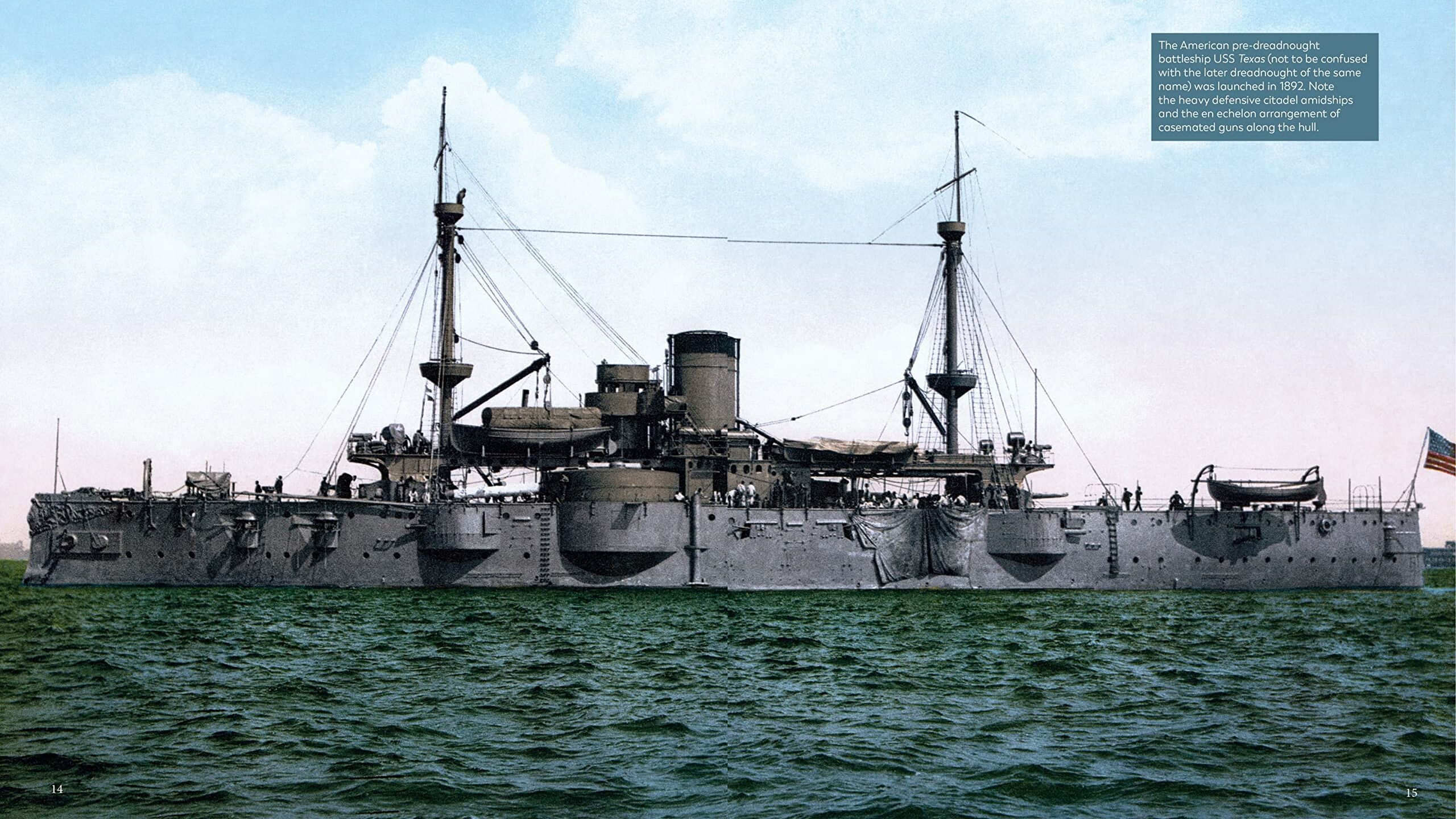

One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power edited by Douglas V. Smith, U.S. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010, 374 pp., notes, photos, $44.95, hardcover.

One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power edited by Douglas V. Smith, U.S. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010, 374 pp., notes, photos, $44.95, hardcover.

Long before there were Top Guns who flew jet fighters at supersonic speed, there were the dauntless naval aviators in aircraft with no cockpits and very little in the way of protection for the pilot. These brave adventurers paved the way for today’s airmen by flying rickety old airplanes known as “wood and wire box kites.”

From these humble beginnings, naval aviation emerged as one of the military arms of the United States that catapulted her onto the world stage. The book follows the birth of naval aviation through both world wars, Korea, Vietnam, and the present era. From the biplanes of World War I to the mighty aircraft carriers of today, naval aviators are in the forefront in protecting America’s interests around the globe.

Victorious Insurgencies: Four Rebellions That Shaped Our World by Anthony James Joes, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2010, 319 pp., notes, index, $40.00, hardcover.

Victorious Insurgencies: Four Rebellions That Shaped Our World by Anthony James Joes, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2010, 319 pp., notes, index, $40.00, hardcover.

As Harvard philosopher George Santayana wrote memorably: “Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” These are prophetic words indeed. And, as the author points out, they are words that should be heeded by government leaders and military strategists when dealing with the guerrilla-style wars that have been fought for thousands of years.

Four rebellions are analyzed in the book: China, between the Nationalist and Communist forces in the 1930s and 1940s; Vietnam, between the French and the Viet Minh from the end of World War II to 1954; the Cuban rebellion fought between the ruling Batista government and Fidel Castro’s insurrectionists; and, finally, the Soviet Union’s catastrophic 1980 invasion of Afghanistan. Although these insurgencies took place in various parts of the world, the victors were able to shift world power in the decades that followed.

“The insurgencies of both the recent and the distant past are a rich storehouse of wisdom,” writes Joes, “that it would be almost criminal to ignore.”

Strangling the Confederacy: Coastal Operations in the American Civil War by Kevin Dougherty, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2010, 233 pp., notes, index, photos, maps, $32.95, hardcover.

Strangling the Confederacy: Coastal Operations in the American Civil War by Kevin Dougherty, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2010, 233 pp., notes, index, photos, maps, $32.95, hardcover.

It came to be known as the “Anaconda Plan.” It was a simple concept: block all the major southern ports and render their armies useless. It was an ambitious scheme, with the blockade stretching for thousands of miles from the Atlantic Seaboard to the Gulf of Mexico and extending up the Mississippi River.

Both sides fought a series of pitched battles to seize the valuable ports. From the Union victory at Hatteras Inlet off the North Carolina coast in 1861 to the Battle of Mobile Bay in January 1864 and the horrific fighting at Fort Fisher one year later, Federal warships and their crews made huge sacrifices.

In the end, the strategy worked. Like the anaconda itself, the Union Navy squeezed the lifeblood out of the South. The flow of supplies was greatly curtailed. Coupled with General Ulysses S. Grant’s ongoing land campaign, the plan put the last nail in the Confederate coffin.

Valleys of Death: A Memoir of the Korean War by Colonel William (Bill) Richardson, U.S. Amy (Ret.) with Kevin Maurer, Berkely Books, New York, 2010, 340 pp., index, photos, $25.95, hardcover.

Valleys of Death: A Memoir of the Korean War by Colonel William (Bill) Richardson, U.S. Amy (Ret.) with Kevin Maurer, Berkely Books, New York, 2010, 340 pp., index, photos, $25.95, hardcover.

Although the fighting in and around the Pusan Perimeter has been told and retold, this new book offers a fresh look at the dark early days of the Korean Conflict. Richardson fought bravely at the terrible debacle at Unsan during the Chosin Reservoir battles. Commanding a 57mm recoilless rifle section, the Philadelphia native was captured by the Chinese and endured nearly three years as a prisoner of war.

During his time as a POW, Richardson continued to defy his captors and was beaten, starved and force-marched until he dropped. Despite all of this, he continued to plan his escape with fellow prisoners. Richardson would be one of the lucky survivors freed after the United States and North Korea signed the armistice on July 27, 1953.

Richardson’s book is a testament not only to himself, but to those other soldiers who fought and died during the “Forgotten War.” More importantly, it is a fitting tribute to the men who suffered as POWs and were fortunate enough to survive their traumatic ordeal of the brutal Chinese Communists.

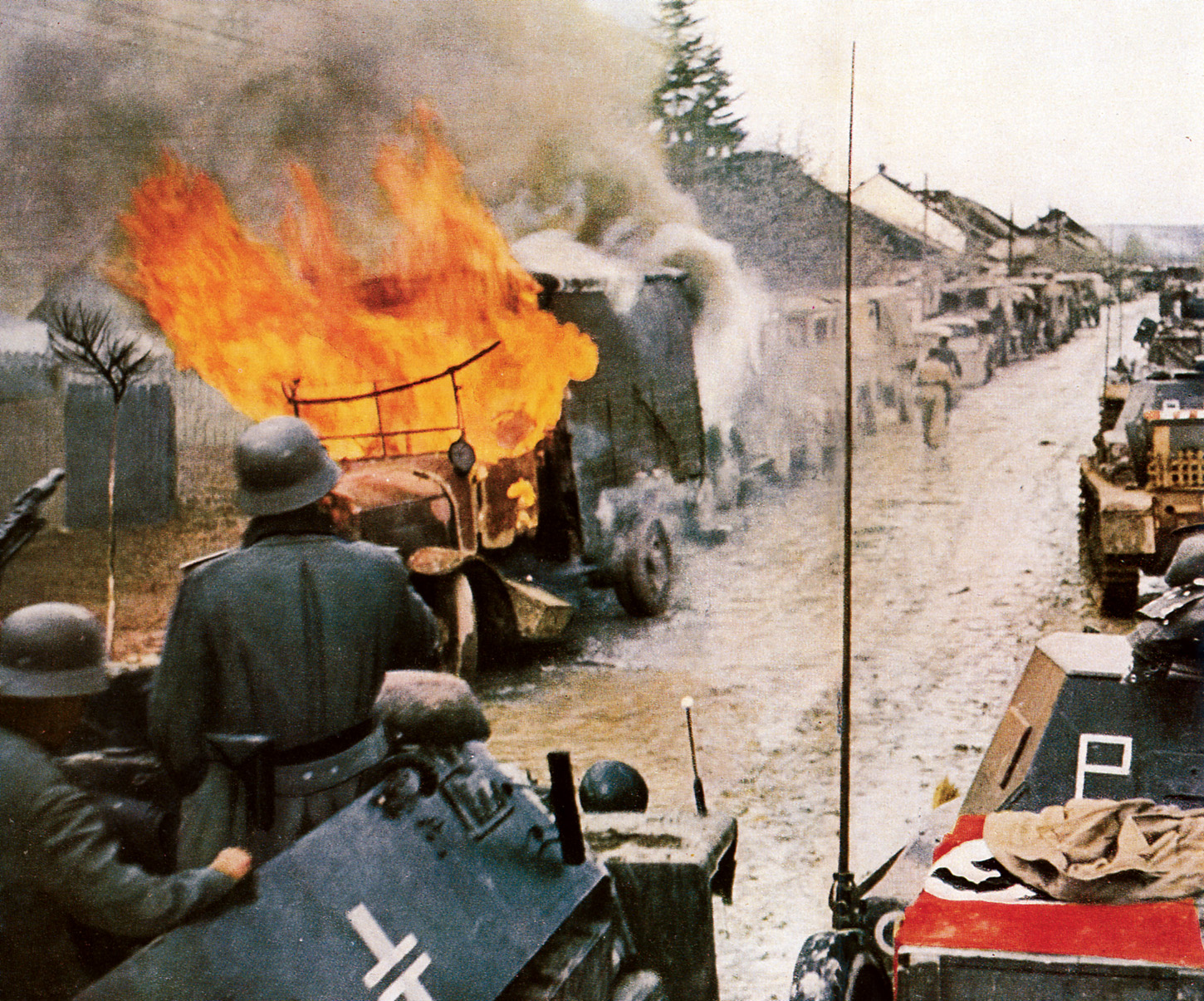

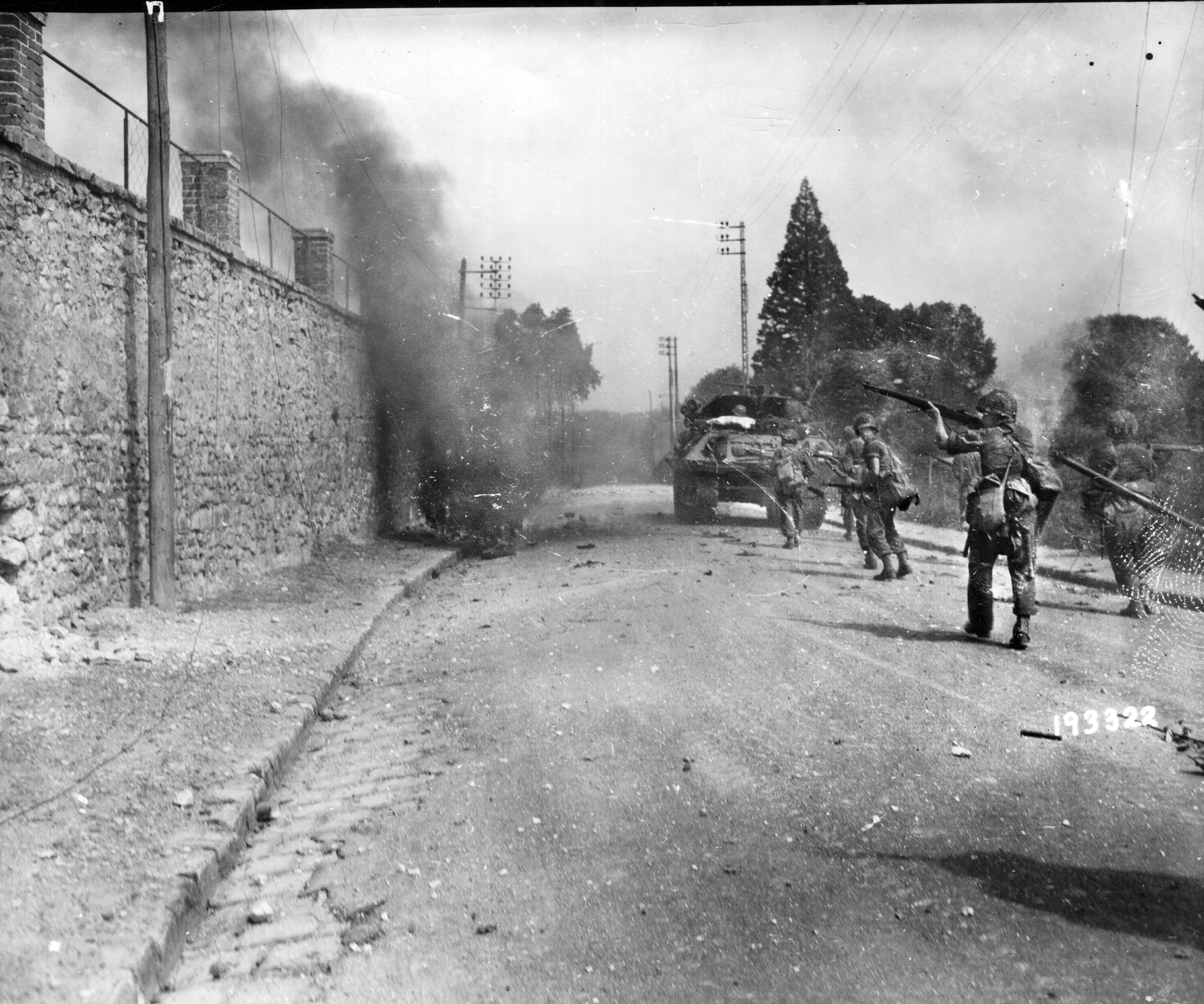

The German Wars: A Concise History, 1859-1945 by Michael A. Palmer, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 256 pp., index, bibliography, photos, $29.00, hardcover.

The German Wars: A Concise History, 1859-1945 by Michael A. Palmer, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 256 pp., index, bibliography, photos, $29.00, hardcover.

It has always been conceded that Germany fielded one of the best armies in both world wars. The inevitable question the author asks is why Germany lost them. He offers several suggestions as to why this occurred. First, the German military did not rethink their strategy as battlefields changed, new weaponry came on the scene, and the transportation of armies drastically altered the face of war. Second, despite a few successes prior to World War I, Germany had no experience in fighting a long, protracted conflict that involved large-scale armies.

Even though they suffered defeat at the hands of the Allies in 1918, the German military leaders still felt they possessed combat superiority. Hence, when World War II erupted, despite their innovative blitzkrieg-style of warfare at the beginning of the war, German leaders found themselves on the losing side again in 1945. The author has provided a provocative look at the methods that Germany used to wage war, and why ultimately they failed.

One of Morgan’s Men: Memoirs of Lieutenant John M. Porter of the Ninth Kentucky Cavalry edited by Kent Masterson Brown, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2011, 288 pp., notes, bibliography, photos, $35.00, hardcover.

One of Morgan’s Men: Memoirs of Lieutenant John M. Porter of the Ninth Kentucky Cavalry edited by Kent Masterson Brown, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2011, 288 pp., notes, bibliography, photos, $35.00, hardcover.

Here is a book that will put the reader right in the saddle as it traces the illustrious career of Lieutenant John Porter, who rode with Confederate cavalry raider Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan. Morgan led many successful raids in Kentucky and Ohio during the Civil War before he was ambushed and killed in Greeneville, Tennessee, in 1864. Those who rode with him were a confident

lot, feeling that they could not be beaten on the battlefield. Porter was one such individual. He tells the story of his countless battle and skirmishes, and how he endured captivity on two occasions.

Despite being in the thick of the fighting, Porter miraculously survived the bloody conflict and returned home at the end of the war. To his dying day, he never regretted his decision to enlist in the Confederate Army. In his opinion, he had ridden alongside one of the greatest cavalry leaders of all time, John Hunt Morgan.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments