By William Stroock

As the fateful day drew to a close, the exhausted soldiers of the German 25th and 82nd Reserve Divisions huddled in their trenches. It was May 30, 1918, and for the past two days the Germans had battled elements of the American 1st Division for control of the small village of Cantigny and its environs. Before them the virgin ground had been churned, the town shot up, and its cemetery turned into a ghoulish battlefield of broken headstones and protruding coffins.

While the Americans had given ground, they had not broken, and they had repulsed every assault the experienced Germans mounted. Over the course of the battle, the Americans had whittled the 82nd Reserve Division down to 2,500 effective personnel. The Battle of Cantigny, the first major assault of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) on the Western Front in World War I, proved that Americans “would both fight and stick,” said Maj. Gen. Robert Lee Bullard, commander of the 1st Division.

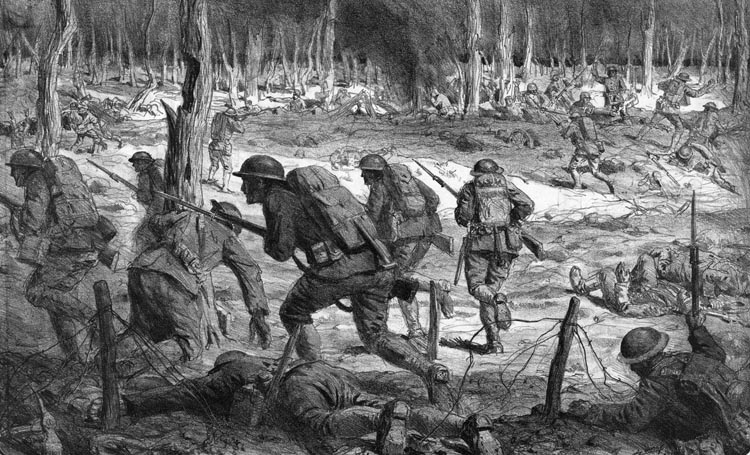

The drubbing had been delivered by the 28th Infantry, later reinforced by elements of the 18th Infantry. The Battle of Cantigny began at 4:45 am on May 28. After a 90-minute artillery barrage, the Yanks advanced with three battalions arrayed along a front of 11/2kilometers. Machinegun companies protected each flank. The Americans overran most German forward positions within the first 10 minutes, although the fighting in Cantigny itself came down to flamethrowers, hand grenades, and bayonets. By 8 am the Yanks were digging in, with the 2nd Battalion occupying Cantigny and the 3rd Battalion deployed to the south.

“The success of this phase of the operation was so complete, and the list of casualties so small, that everyone was enthusiastic and delighted,” wrote Colonel George Marshall, who planned the attack. “[However], trouble was coming thick and fast.”

That afternoon, the French withdrew their supporting artillery to deal with a new German offensive. At the same time, German 210mm guns pounded the American positions and tore up the communications wires carefully laid by the 28th Infantry’s engineers. The German counterattack began in the evening and continued into the next morning. The German commander in chief, General Erich Ludendorff, had ordered that the American positions around Cantigny be utterly destroyed for the same reason AEF commander General John J. Pershing ordered that it be held at all costs. “For the 1st Division to lose its first objective was unthinkable and would have had a most depressing effect on the morale of our entire Army, as well as those of our Allies,” wrote Marshall.

The Germans pushed the 2nd Battalion out of its forward positions and into Cantigny proper. To the south, the 3rd Battalion held firm, delivering deadly rifle and machine-gun fire into the attacking Germans. American artillery also seriously disrupted the German attack. However, German artillery, which had survived due to ineffective American counterbattery fire, inflicted heavy losses on the Americans. As a result, the 28th Infantry’s commander, Colonel Hanson E. Ely, was forced to bring his only two reserve companies forward. The Germans launched a second counterattack on the morning of May 29, but this was broken up once more by American rifle and machine-gun fire. German commanders realized that the Americans were probably advancing no farther and halted the attacks, content to harass instead. When the 28th Infantry was pulled off the line on May 30, it left more than 1,000 of its number on the battlefield.

The assault had been of the utmost importance to Pershing. Days before the attack, the men of the 18th Infantry had been withdrawn to the rear area. They meticulously planned and rehearsed the assault against an exact replica of the German defenses in and around Cantigny. In these maneuvers, Pershing’s idea of open warfare was emphasized as was staff work and above all maintaining communications between the front and headquarters. This extensive planning and preparation were typical of Pershing.

When America entered the conflict, Pershing’s first task was to prepare the AEF for modern war. The Americans desperately needed training and organization. The U.S. Army had spent the last two generations fighting imperial wars. In 1917, most of the U.S. Army was stationed on the Rio Grande. Pershing, of course, had become famous for his chase of Poncho Villa in Mexico and before that, for fighting the Moros in the Philippines. America’s occupation of the islands in 1898 had led to a four-year insurgency. Before the war with Spain, the small American army had spent a generation subduing Indians in the American West. Bullard had ridden in the Geronimo campaign.

The U.S. Army had a deep institutional memory of the American Civil War. Bullard grew up in Alabama hearing stories from veterans of the siege of Vicksburg. Lt. Gen. Hunter Liggett, who would eventually command 500,000 men in the American First Army, in 1907 went on a staff ride in Virginia with a former Confederate cavalry general. Pershing himself harkened back to the American Civil War when considering the means by which the AEF would be raised. In his memoirs he made reference to “the evils of the volunteer system in the Civil War, with appointment of politicians to high command” and noted that because of battles such as Vicksburg and Petersburg “Americans were no strangers to trenches.”

To build the AEF, Pershing established an operation and training staff and personally oversaw its direction. The staff developed a school system on the British model, which had impressed Pershing. A general staff college with a three-month curriculum was founded as were schools to teach the use of new weapons developed over the course of the war. These included schools for machine guns, mortars, flamethrowers, and hand grenades.

Pershing also approved of the British method of trench warfare. “They taught their men to be aggressive and undertook to perfect them in hand-to-hand fighting with the bayonet, grenade, and dagger,” he wrote. British and French officers lectured at the American schools. Despite the advent of these modern weapons, Pershing insisted that an infantryman was, at his core, a rifleman.

“My view was that the rifle and bayonet remained essential weapons of the infantry,” he wrote. Intense rifle training fit into Pershing’s view of aggressive, offensive warfare. An AEF training pamphlet declared in part, “All instruction must contemplate the assumption of a vigorous offensive. This purpose will be emphasized in every phase of training until it becomes a settled habit of thought.” Pershing believed that in three years of trench warfare Allied troops had become too defensive and abandoned offensive warfare.

Pershing was determined that the AEF would not fall into the same trap of relying upon around-the-clock artillery bombardment and modern specialty weapons. Rather, Pershing preached open warfare. In Pershing’s style of war, American divisions would force their way through German positions into the open areas in their rear. From there the Doughboys would fight a battle of maneuver aimed at outflanking and destroying German formations. Pershing insisted that, “Instruction in this kind of warfare was based upon individual and group initiative, resourcefulness, and tactical judgment.” Although the AEF troops would learn the art of trench warfare, Pershing was adamant that they strive for open warfare. To this end, the Doughboys were to learn combat skills that they would need to participate in offensive operations. In Pershing’s thinking, the war would be won by American riflemen.

Despite Pershing’s emphasis on open warfare, AEF divisions would still have to puncture German defenses. To punch through, Pershing formed American divisions into behemoths with four infantry regiments, an artillery brigade of three regiments, an engineering brigade, and an independent machine-gun battalion. In all, American divisions numbered 28,000 men, roughly the size of an Allied corps. An American brigade—two infantry regiments and a machine-gun battalion—numbered 8,500 men, which by that point in the war was larger than most Allied and German divisions. American rifle companies were tactical mammoths numbering 250 officers and men divided into four platoons. In Pershing’s plans, the AEF would eventually number three million men in 80 divisions. He envisioned the AEF gradually taking on the burden and bearing the brunt of the war. To that end, Pershing planned for an AEF attack into Alsace-Lorraine with the goal of pushing into Germany and destroying German industrial capacity in the Rhine and Saar valleys.

When America entered the Great War, both the French and the British proposed schemes that would see American troops integrated into their armies. One French memo, quoted by Pershing, actually called for Americans to enlist in the French Army. The British proposed the same system in a memo to Pershing: “If you ask me how your force could most quickly make itself felt in Europe, I would say by sending 500,000 untrained men at once to our depots in England to be trained there and drafted into our armies in France.”

A furious row ensued in which Pershing simply refused to accede to the Supreme War Council’s wishes. Foch insisted, in Pershing’s words, that “the war might be over before we were ready.” To which Lloyd George added, “Can’t you see that the war will be lost unless we get this support?” Pershing held out and won. While the Abbeville Agreement, as it was named, called for more American infantry to be shipped across the Atlantic, it also stated, “It is the opinion of the Supreme War Council that, in order to carry the war to a successful conclusion, an American army should be formed as early as possible under its own commander and under its own flag.”

Throughout the winter of 1917-1918, Ludendorff had worked hard to prepare German forces to defeat the Allies before the full strength of the American military might be brought to bear on the Western Front. He shifted and retrained German forces, some of whom would serve as shock troops spearheading new attacks. Ludendorff did not envision one grand offensive, but rather a number of offensives designed to wear down the Allies and take advantage of the conflicting priorities of the British and French commands.

The German Somme and Lys offensives were launched in March and April, respectively. The Aisne Offensive, the third that the Germans unleashed against the Allies that spring, would include pivotal battles involving the AEF, such as Cantigny, Chateau-Thierry, and Belleau Wood. The Aisne Offensive began on May 27 and lasted until June 17. The Germans followed their first three offensives with two more, launching the Noyon-Montdidier Offensive on June 9 and the Champagne-Marne Offensive on July 15. The Second Battle of the Marne in mid-July saw the Germans establish bridgeheads across the Marne River, but it also saw the tide turn against the Germans.

Ludendorff pushed 30 German divisions across the Marne, overwhelming the seven Allied divisions there and creating a salient threatening Paris. At that point in the war, Pershing had eight divisions which he described as complete and ready to join the fighting. Of these, the U.S. 1st Division was already at Cantigny, while three more—the 2nd, 26th, and 42nd—were in line along a quiet sector. On May 30, Pétain called on Pershing to send what American troops he could to stem the German tide. Pershing immediately rushed the 2nd and 3rd Divisions to Chateau-Thierry at the southern tip of the German salient.

The first American unit to arrive was the 3rd Division’s 7th Machine Gun Battalion. All such battalions comprised two-machine gun companies, each armed with 16 French-made Hotchkiss machine guns. The Hotchkiss was fed by a 30-round magazine, could fire 600 rounds per minute, and had a range of 3,800 yards. Each company was in turn divided into three machine-gun platoons of four guns each and a headquarters platoon. American doctrine called for machine-gun battalions to be deployed several hundred yards behind the line to provide fire support for both defensive and offensive needs. Division machine-gun battalions were completely motorized.

As French soldiers of the shattered 10th Colonial Division fled south across the Marne, the 7th Machine Gun Battalion arrived opposite the town of Chateau-Thierry. A squad with two Hotchkiss guns was immediately sent across the river into the village. The rest of the battalion deployed on the south bank of the Marne, with eight guns covering a small wagon bridge that linked the town to the south bank and the other nine covering a railway bridge some 500 yards downstream. These troops traded fire with the Germans while the rest of 3rd Division rushed north to positions on the south bank of the Marne. For the next three days, the French and 7th Machine Gun Battalion held the Germans on the north bank. The report of the French commander of the 10th Colonial Division reads in part, “Immediately the American reinforced the entire bridge, especially at the approaches of the bridge. Their courage and skill as marksmen evoked the admiration of all.” He also noted, “Here again the courage of the Americans was beyond all praise. The Colonials themselves, though accustomed to acts of bravery, were struck by the wonderful morale in the face of fire, the impossibility and the extraordinary sangfroid of their allies.”

While elements of the 3rd Division were going into line southeast of the salient, the 2nd Division was taking up positions on the salient’s southwest side. This division was a hybrid containing the 3rd Brigade, U.S. Army, and the 4th Brigade, U.S. Marines. The division had been training near Chaumont after spending a month in a quiet sector near Toulon. The 2nd Division went into the trenches near Chateau-Thierry on the night of June 3-4 as French troops streamed passed them toward Paris. Captain William O. Corbin of the 5th Marines was accosted by a fleeing French officer who advised the Americans to retreat. When Corbin relayed the message to Major Lloyd Williams, his commanding officer, Williams said, “Retreat? Hell, we just got here!”

The next day the Germans advanced through unspoiled fields against the Marines of the 4th Brigade. They were met by machine-gun and concentrated rifle fire. Here, Pershing’s ideas on marksmanship were tested on the battlefield. Up and down the line the Marines held and forced the Germans to break off the attack. Colonel Albertus Catlin, who commanded the 5th Marines, described the scene; “Then, under that deadly fire and the barrage of rifle and machine gun fire, the Boche stopped. It was too much for any man. They buried in or broke to the cover of the woods and you could follow them by the ripples of the green wheat as they raced for cover.”

By June 5, two American divisions, the 2nd and the 3rd, totaling nearly 60,000 men, were on the Marne Salient. These were at the disposal of the French XXI Corps commanded by General Jean Degoutte, who believed the time was right for limited, local counterattacks. In this Degoutte had Pershing’s complete support. As such, he ordered the 2nd Division to attack German positions at the southwestern edge of the salient at Belleau Wood.

Belleau Wood was untouched by the ravages of war in 1918. Running north to south, it was about two miles long and a half mile wide. In the words of the 2nd Division historians, “The Forest of Belleau was in full leaf and in a state of nature.” The village of Bouresches bracketed the wood in the northeast, while the town of Torcy lay to the northwest. The 4th Brigade was deployed in the Lucy-le-Bocage to the south and the Champillon Wood to the immediate west. The brigade was commanded by Army Lt. Gen. James Harbord, a West Point graduate who had fought in Cuba, the Philippines, and the Poncho Villa campaign. Harbord had been Pershing’s chief of staff for a time before Pershing placed him in charge of the freshly organized 4th Marine Brigade.

Harbord’s plan called for the 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines to advance into the wood from the south. From there the 3rd Battalion was to push on through the southern end of its sector and take the village of Bouresches, while the 2nd Battalion advanced through the northern end to take the town of Torcy. At the same time, the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines would advance in the center from the west. The 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines guarded the southern flank and connected the 4th Brigade with the 3rd Brigade. On the left, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines would advance against German positions atop Hill 142.

French intelligence officers believed Belleau Wood to be lightly defended; however, this was not the case. Occupying the wood were elements of the German 197th and 237th Divisions. The American attack would fall on the dividing line between the two forces, hitting two battalions of the German 197th Division on the left of the wood and one of the German 237th on the right in the wood proper. These divisions had spearheaded the German assault in the direction of Rheims, and their ranks had been thinned by several days of fighting.

The 1st Battalion, 5th Marines began the Battle of Belleau Wood at 3:45 am on June 6 with its assault on Hill 142. The attack got off to a bad start. Two infantry companies and the machine-gun company were late getting to their start positions. The battalion commander elected to attack on schedule anyway. Despite being understrength, the 1/5 Marines made good progress, and some elements even got to the outskirts of Torcy, although these were driven back. The Marines suffered more than 400 casualties in the fighting.

The main attack by the 6th Marines got underway at 9 pm with a short, badly coordinated artillery barrage that had little effect on the Germans in the wood. Harbord’s rationale for the barrage was that a lengthy effort would alert the Germans. The 3/6 Marines and the 2/6 Marines climbed out of their trenches and began the trek across the largely unscathed ground before the wood. They advanced in four skirmish lines, easy targets for the Germans, who inflicted frightful casualties upon the Marines.

The 3rd Battalion managed to get into Belleau Wood but was unable to push on to its second objective. Instead, it became bogged down at the wood’s edge and fought dogged German defenders at point-blank range and in hand-to-hand combat. At the same time on the right, the 2nd Battalion advanced north against light resistance. One company took the town of Bouresches north of the wood. The Germans brought the town under fire but did not attack. A Marine company at that location was reinforced by two other companies, and by midnight the town was safely in American hands. The main attack, however, had failed. As it was taking heavy fire, the 3/6 Marines pulled back to its jump-off points.

On Harbord’s orders, the Marines stood pat throughout the next day. On June 8, the 3/6 Marines did try to work its way into the wood’s southern tip, but this effort was easily repulsed by the Germans and the battered battalion retreated once again. The first phase of the attack on Belleau Wood had been disastrous. The lack of proper artillery preparation was partly to blame, but the most important factor in the American failure was their poor tactics. The three Marine battalions advanced through clear ground in open order. “It was a beautiful deployment, lines all dressed and guiding true,” wrote Marine Captain John Thomason.

Captain George Hamilton, who commanded a company in the 3rd Battalion, wrote of passing through a field and into the wood only to have to traverse another open field. “Further on we came to an open field—a wheatfield full of red poppies—and here we caught hell. Again it was a case of rushing across the open and getting into the woods.” The Marines were not practicing open warfare. They were replicating tactics their grandfathers used more than a half century earlier and getting slaughtered.

After the first day of the assault on Belleau Wood, Harbord took stock of the disappointing results. He concluded his report to Bundy as follows: “The Brigade can hold its present position but is not able to advance.” Indeed, the attack had cost more than 1,000 casualties, and the Marines were exhausted. Battalion commanders pleaded that their men needed rest. Harbord was particularly displeased with the reports sent back by his commanders. In an 11-point communiqué, he called them vague and demanded more detail including concrete numbers of friendly and enemy casualties and precise map coordinates. “Losses are heavy may mean anything,” he admonished. He told his officers to use what resources they had and “not count on reinforcements.”

With the world watching, the Allied press was already writing about America’s great victory in Belleau Wood, and with his own reputation at stake Harbord ordered another attack. This one came on June 10. The plan ordered the 3/6 Marines, taking up positions directly south of the wood, to attack due north. At the same time the 2/5 Marines, operating west of the wood, was to attack east into the center. This time artillery fire was better coordinated, with barrages bracketing German positions and targeting troop concentrations. Beginning at 4:30 am, the 3/6 Marines made excellent progress advancing north and reported by 8 am that they had achieved all their objectives. In fact, they advanced so rapidly because the Germans had abandoned the southern edge of the wood. The Marines had actually stopped several hundred yards short of their objectives. The 2/5 Marines fought their way into the wood, but because the 2/6 Marines had stopped short they were not adequately supported and unable to complete their sweep to the east. About half of Belleau Wood was in Americans hands, but the northern half was still occupied by the Germans.

On June 12, the attack was renewed. The 2/5 Marines led the assault and actually pushed through the north of the wood and into the open. The Germans now only held a swath in the northeast part of the wood. The 2nd Division’s official history describes the Marines’ hold on the wood as “precarious.” With the Germans still in the northwest sector, contact was established with American units on the left. On the right, the 23rd Infantry occupied Bouresches. Over the next few days, the German artillery pounded Belleau Wood. On June 12, the Germans launched a general counterattack focused on Bouresches, but the Marines turned them back. The Germans’ presence in the wood was not eradicated until June 23 when the 3/5 Marines attacked and overran their positions in the northwestern sector.

As the 4th Brigade’s sector was settling down, the 3rd Brigade was tasked with taking the village of Vaux. The brigade had been in the line for weeks; it had aggressively patrolled and mapped German positions in Vaux. The attack was carried out by the 9th Infantry and incorporated the lessons of Belleau Wood. German positions were subjected to a 12-hour preparatory bombardment, which included a gas attack 90 minutes before jump off. American troops advanced before a rolling barrage, with special units delegated to the advancing battalion’s flanks to maintain contact between advancing sections. German defenders in Vaux were quickly overwhelmed. A planned German counterattack was broken up by artillery fire. The 9th Infantry quickly consolidated its positions and prepared either to advance or receive the expected German counterattack. In contrast to Belleau Wood, Vaux was a model American attack.

After these actions, at Foch’s request Pershing placed more American divisions in line. The 26th Yankee Division and the 42nd Rainbow Division had relieved the 1st and 2nd Divisions, while the 28th Keystone Division became part of Dougette’s corps reserve. These divisions engaged German forces in a series of sharp skirmishes along the Marne. The most famous of these was fought by the 3rd Division, whose unwavering defense earned it the nickname “Rock of the Marne.” Here the 38th Infantry stopped a German attack across the Marne, inflicting devastating casualties upon the Germans as they advanced down the Surmelin Valley. The 38th Infantry was notable for its acerbic commander, Colonel Ulysses Grant McAlexander, who carried a Springfield Model 1903 rifle and spent much of the battle sniping at Germans and organizing counterattacks.

While American forces came into the line, Ludendorff’s offensive proceeded with a new effort launched against Rheims. As the Germans pushed their dwindling reserves into the salient, Foch determined that the time for a counterattack had arrived. He delegated the mission to the French Sixth and Tenth Armies. American forces participated with the American III Corps joining the Tenth Army on the northwest corner of the salient. The III Corps was newly formed; it contained the battle-hardened 1st and 2nd Divisions and was commanded by Bullard. The Franco-American attack depended on achieving absolute surprise. Units moved to the front only at night, and the usual massive preparatory artillery bombardment was eschewed.

Pershing was elated that American forces were going into battle under a corps organization. However, a few days before the attack Bullard determined that his new corps lacked the necessary higher echelon staff and organization. “Every hour of delay meant increasing chances of discovery by the enemy,” he said. “I therefore decided … that my two divisions should go into the battle as divisions in a French Corps already on the ground, with its orders and plans all ready. This was done.” Bullard placed the 1st and 2nd divisions at the disposal of the French XX Corps.

The French XX Corps now consisted of the two American divisions, the 1st Moroccan Division, and the French 58th and 69th Divisions, with General P.E. Berdoulat commanding. The corps’ mission was to attack the northwestern corner of the salient and cut the road running from Soissons to the tip of the salient at Chateau-Thierry, severing German communications and strangling the salient. The attack was conducted north to south by the American 1st Division, the 1st Moroccan Division, and the American 2nd Division.

The 1st Division attacked along a 2,800-meter front. The Americans were confronted not only by the German 6th and 42nd Divisions, but also by several physical obstacles. These included German-occupied farms and three ravines from east to west at Missy, Ploisy, and Chazelle. The first day’s plan called for the division to advance in three stages culminating with the seizure of Chaudin two miles east of the American start line.

The attack began at 4:45 am; the subsequent fighting illustrates many of the problems tactical commanders faced in the Great War. The Americans achieved their first objective by 5:30 am. As they pressed forward they ran into the German-held farms, each transformed into a strongpoint by the defenders. The Americans engaged the defensive positions, slowing the overall advance. Elements of the 28th Infantry, occupying the American extreme left flank, advanced out of their zone and across French lines to engage a strongpoint from which they were taking fire. After the initial advance, the brigade slammed into the Missy Ravine, nearly a kilometer wide and heavily defended by the Germans. The lead battalion advanced into the ravine and was chewed up by German machine guns. The support battalion followed and took heavy casualties, though it was able to push through the ravine while the regiment’s reserve battalion deployed along the western edge.

At the same time, German troops hiding in a cave within the ravine counterattacked and were dealt with by the support battalion’s reserve company. To the south, the 26th Infantry also encountered stiff resistance, but it pushed to the east end of the ravine. Farther south, the 1st Brigade took heavy casualties in the fight for Chaudin and it tried for the second objective. It was stopped by German forces dug in on high ground before the Chazelle Ravine. As a result, the 1st Brigade was a mile behind the 2nd Brigade’s advance.

To the south, beyond the 1st Moroccan Division, the 2nd American Division attacked along a five-mile front. Its mission was to advance about two miles and take the villages of Vauxcastille and Vierzy. From there, the Americans would eventually press on to the Soissons and Chateau-Thierry road. The 2nd Division’s deployment was similar to the 1st Division’s—two brigades each on a two-regiment front advancing in battalion columns of assault, support, and reserve. However, the division had unique problems. It received its orders a mere 30 hours before the attack was to begin, and Harbord had to scramble to gather his dispersed units. The subsequent rush to deploy led to jammed roads, and with mere hours until the jump-off time some battalions were five and six miles from the front. While every battalion was able to get positioned in time, many had to leave crucial equipment and men, such as machine-gun companies and 37mm guns, behind.

Advancing behind a rolling barrage, the 2nd Division got off to a good start. Within five minutes many units overran German forward positions. The 3rd and 4th Brigades pushed on and by the afternoon had reached their second objective, the eastern side of the Vauxcastille Ravine. The far side was taken in a quick rush that cost the Americans heavy casualties. Next lay the line along Vierzy village, which the Germans had turned into a fortress. The 2nd Division overran this line, though it did not take Vierzy proper. Lead units of the 4th Brigade had strayed north and engaged targets in the Moroccan zone. German pockets of resistance remained in the American rear, and several American units were forced to turn their attention to subdue them.

Throughout the next day, the 2nd Division pushed on, achieving a line about a mile east of Vierzy, which the Germans still held despite multiple attempts to dislodge them. The Germans finally pulled out on the morning of July 19. The 2nd Division remained along this line for the next three days. On July 22, the Germans counterattacked all along the American line but were repulsed with heavy casualties. On July 19, the 2nd Division, after suffering 4,300 casualties, was relieved by a French division. The 1st Division stayed in line until July 22 and lost 6,900 men. Soissons was a victory for the Americans.

The attack at Soissons blunted the final German spring offensive and put the 1st Division astride the Soissons and Chateau-Thierry road with the 2nd Division near it. Maj. Gen. Charles P. Summerall, commander of the 1st Division, noted with pride that the Germans did not take a single prisoner from his division, while it captured 3,500 Germans. Of his division, Summerall noted, “While no serious mistakes were made, a number of details required improving.”

American units still had to master the art of advancing in unison and maintaining contact with flanking units. They also at times failed to consolidate their positions by clearing out pockets of German resistance and readying for the inevitable German counterattack. Pershing wrote triumphantly of Soissons, “We had snatched the initiative from the Germans almost in an instant. They made no more formidable attacks, but from that moment until the end of the war they were on the defensive.”

During the spring of 1918, the AEF had gained valuable experience, first in trench warfare and then in offensive and defensive action. The Cantigny and Vaux attacks had been well executed. They had incorporated all arms and had simple, attainable objectives. The Belleau Wood attack was deeply flawed, relying on nearly suicidal open field charges and vague directives such as “clear the wood.” Soissons was far more complicated than earlier offensive actions and much better executed than Belleau Wood, although the Americans still had much to learn about maintaining a steady advance. While Pershing’s open warfare ideas were proving to be disastrous in attack, his emphasis on marksmanship proved devastating in defense. All across the Marne Salient, German counterattacks slammed into highly accurate American rifle fire.

A few days after Soissons, Liggett’s I Corps, comprising the 3rd, 4th, 26th, and 42nd Divisions, attacked in the center of the Marne Salient. Bullard’s III Corps later joined the assault. On September 12, the freshly constituted American First Army began a four-day offensive against German forces in the St. Mihiel Salient, a move Pershing saw as a precursor to his planned offensive into Germany. On September 26, the AEF launched its grand offensive in the Meuse-Argonne, an effort spearheaded by the First Army under Pershing and then Liggett, and formed the American Second Army under Bullard.

In the end, Pershing had defeated not only the Germans, but also the Allied commanders who had tried so hard to erase the independence of American units that fought on the Western Front.