By Kevin M. Hymel

Donald Malarkey’s comrades thought highly of him as a warrior and as a man. Staff Sergeant William “Wild Bill” Guarnere considered him his hero. Lieutenant Lynne “Buck” Compton thought him “a staunch patriot who truly understands the principles for which we fought.” Major Richard “Dick” Winters called him “an outstanding soldier in combat” and “an esteemed friend.”

The paratrooper from Oregon fought with Easy Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division across France, the Netherlands, and Belgium and into the heart of Germany. In a unit filled with nicknames—Skip, Shifty, One-Lung, and Gonorrhea—he was simply known as Malark. Don Malarkey passed away on September 30, 2017, in Salem, Oregon, at the age of 96.

From the hedgerows and villages of Normandy to the bridges and dikes of the Netherlands, from the frozen foxholes around Bastogne, Belgium, to Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest, Don Malarkey took everything the Germans could throw at him and survived World War II without serious injury, but the mental scars of seeing his buddies wounded and killed haunted him for the rest of his life. He became famous in Dr. Stephen Ambrose’s 1992 book Band of Brothers: E Company, 506th Regiment, 101st Airborne from Normandy to Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest, and the 2001 HBO miniseries of the same name.

“Little Donnie” Malarkey’s Early Years

Little Donnie Malarkey grew up in Astoria, Oregon, the son of Leo and Helen, one of four children. He spent his youth playing marbles, swinging from trees, swimming in the Nehalem River, diving for crawfish, and hunting birds with a bow and arrow in cottonwood forests that smelled of blackberries. He was raised on stories of his two uncles who fought and died in World War I and who, he had been told, had never given up. At the age of 12, he made his first parachute jump, leaping off the roof of his parents’ house clutching an umbrella. In high school he bussed tables at the Liberty Grill, blended flour at a mill to make money for college, and dated his sweetheart Bernice Franetovich.

He was attending the University of Oregon when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and left after his freshman year to work at a machine shop in Portland. Although the Marine Corps rejected him, the Army drafted him and he immediately volunteered for the paratroops. Sent to Toccoa, Georgia, he joined Captain Herbert Sobel’s Easy Company. Sobel worked Malarkey and the rest of the company hard, leading them on runs up and down a local mountain named Currahee at all hours of the day and night. Malarkey grew to hate Sobel, wanting to tie him to a pine tree and “use him for slingshot practice,” but by the end of the war he credited Sobel for keeping him and other Toccoa veterans alive.

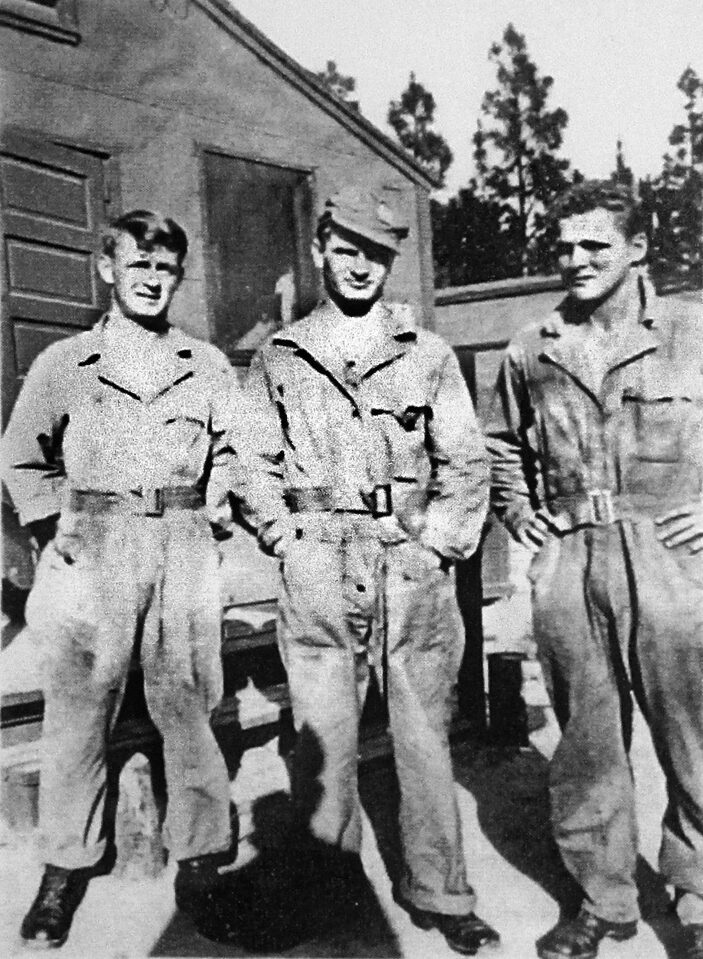

It was at Toccoa that Malarkey met his soon-to-be best friend, Warren “Skip” Muck, from upstate New York. Both paratrooper hopefuls enjoyed a good laugh, good music, and talking about their girlfriends. Muck dated a girl named Faye Tanner, and her letters to him, as well as Bernice’s to Malarkey, kept the men’s spirits up during training. The two served together in Easy’s mortar platoon and often ran up Currahee elbow to elbow. When Malarkey exhausted himself during the 506th’s grueling 120-mile march from Toccoa to Atlanta, he had to crawl to the mess tent. Muck spotted him, took his mess kit, and filled it for him. Muck also stayed with him through the rest of the march, urging him on until they reached Atlanta.

After earning his jump wings at Fort Benning, Georgia, and completing further training in the United States and Great Britain, Malarkey parachuted into Normandy, France, to avenge his two uncles. As he headed to the rally point with a few other Easy men, he passed a group of German prisoners, one of whom had worked across the street from Malarkey’s machine shop in Portland. The two exchanged a few words before Malarkey hurried off. “I’d only been at war for a few hours,” he later wrote, “and already I was learning stuff I hadn’t been taught in training. Namely, that the guy trying to kill you—and that you’re trying to kill—could be somebody who once worked in an American defense plant, across the street from where you later worked. Strange thing, war.”

Malarkey’s Contribution to the D-Day Invasion

Later that day Malarkey joined 15 other paratroopers from his battalion, led by Lieutenant Winters, in an assault on four German 105mm artillery pieces firing on Utah Beach, where soldiers of the 4th Infantry Division were making their way ashore. Malarkey led the assault until Winters stopped him—his rifle was out of ammunition. “[Winters] probably saved my life,” recalled Malarkey. Once rearmed, Malarkey helped kill some of the German gunners with a hand grenade and capture another gun.

It was after his charge that Malarkey did something very human, and very stupid. He bolted from cover to retrieve a Luger pistol from a dead German. Despite Lieutenant Winters’ shouts to stay put, Malarkey reached the dead German only to discover he had an artillery sighting device on him. Malarkey dashed back to cover as bullets kicked up dirt around his feet “like a late-spring hailstorm back in Oregon,” he later recalled.

As Malarkey dove into the gun pit, his helmet fell off. He lay on his back panting while bullets smacked into the gun above him, dropping burning fragments onto his face. As he rolled over, he heard Sergeant Bill Guarnere call to him: “Malark, we’ll time the bursts.” Guarnere was in the trench about five feet from him. So Malarkey and Guarnere began counting the dead time between the enemy’s machine-gun bursts.

“Okay,” called Guarnere, “next burst ends, get your ass over here.” Silence, then Guarnere shouted, “Now!” Malarkey bolted and made it to cover. “Way to go,” Guarnere congratulated him, “you stupid mick!”

As the paratroopers departed the battlefield, Malarkey covered the withdrawal by firing a 60mm mortar. When American tanks showed up, he joined the other men in clearing the field of Germans. Days later, he took part in the attack into Carentan, where he witnessed Chaplain Dan Maloney standing exposed in a street administering last rites to dying paratroopers. The next day, while defending Carentan from a German armored thrust, Malarkey received his first wound of the war when shrapnel from a mortar round tore through his right hand. He had it quickly bandaged and went on.

Once the fighting ended, however, Malarkey proved he still knew how to have a good time. When the division sailed back to Great Britain, he helped a fellow paratrooper smuggle a motorcycle onto their boat, and the two used it to barrel across the English countryside, Malarkey in the sidecar.

Eindhoven and Bastogne

After almost two months in England, Malarkey parachuted into the Netherlands, where he helped capture the town of Son and the city of Eindhoven. The Germans, however, counterattacked outside the town of Nuenen, and Malarkey and a few of his buddies tore down a house door and used it as a stretcher to pull his wounded lieutenant, Buck Compton, to safety. Later, when a German attack on the main road north, called “Hell’s Highway,” split Easy Company in half, Malarkey found himself with Guarnere and a Dutch family in the basement of their house. When the Germans cut the highway again, Malarkey pulled burning British tankers out of their tank and dropped mortar shells on a German tank until it withdrew. Before departing Holland, he also took part in Operation Pegasus, the rescue of British paratroopers stuck on the north bank of the Lower Rhine River, and he captured a handful of patrolling Germans.

Malarkey got a reprieve from the war when the division was pulled off the line and moved to Mourmelon, France, where he won $5,000 shooting craps. The break proved short lived when three German armies attacked into Belgium and Luxembourg on December 16, 1944. The entire 101st was trucked to Bastogne, Belgium, before the Germans surrounded the town. As Malarkey made his way to the front, he grabbed a shovel off a knocked-out tank and used it to help the men in his platoon dig foxholes.

During the week-long siege of Bastogne, temperatures dropped and snow fell. Malarkey wrapped his legs in burlap sandbags and poured water over them, reasoning that the resulting ice would insulate his legs from the cold. He believed it worked. It was after the siege had been broken that Malarkey began to feel the stress of combat. He lost a number of friends. Some killed, others wounded, and one, Buck Compton, overcome by battle fatigue. He saw Guarnere and Joe Toy each lose a leg in heavy shelling. It was then that Malarkey almost succumbed to shooting himself in the foot to get off the frozen battlefield. When Winters offered him a break to come off the front line, he refused, opting to stay with his men. He did not want to quit.

It was soon after that, on January 9, 1945, that the worst happened. After a heavy shelling, Doc Roe, one of the company medics, walked up to him in the snow and told him, “Malark, I’m sorry, but it’s Skip. He’s dead. Penkala too.” Malarkey was too numb, too cold, and too tired to react. Winters again offered to pull Malarkey off the line, but again Malarkey refused. He buried the feelings about his friend. There was a battle to fight; he would mourn later. Almost a month after Muck’s death, Malarkey wrote Faye, Muck’s girlfriend, and told her how hard it was to go on fighting without “the Skipper.” He promised to visit her after the war if he was ever in New York.

The fighting and killing went on. During the attack on the town of Foy, a mile north of Bastogne, two men were killed next to Malarkey, one a mortar man hit by machine-gun fire, the other a corporal, shot by a 16-year-old sniper in a barn window. Malarkey killed the sniper with his Thompson submachine gun, surviving the winter campaign while sustaining only a dent in his helmet from a strafing American Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter aircraft.

In February, Easy Company moved to Hagenau, France, overlooking the Moder River. There, Malarkey again credited Winters with saving his life when Winters called off a river-crossing patrol, sparing the men the risk of injury and death with the end of the war in sight.

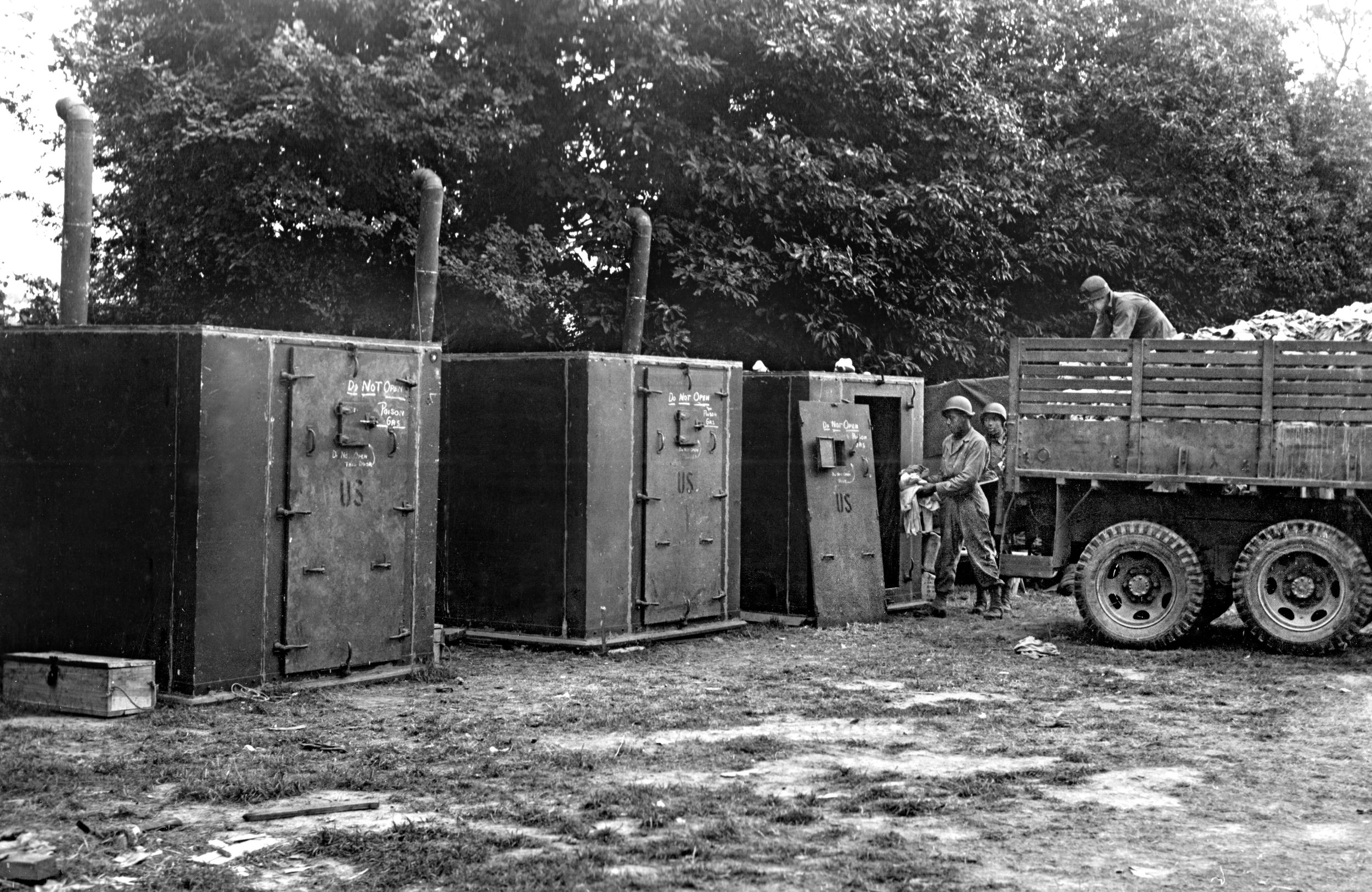

it from German attack. Don Malarkey lost numerous friends in the woods around Bastogne.

“Skip” Muck’s death haunted him for the rest of his life.

While in Germany as the war wound down, Malarkey woke up one night with fever and chills. He was sent to an Army hospital in Liege, France. By then he had served 177 days in combat, the most of any paratrooper in the company. He never quit, and he paid the Germans back for killing his two uncles. After Germany surrendered, he rejoined the unit in Saalfelden, Austria, before returning home.

Malarkey’s transport ship brought him to New York, where he connected with Bernice, who was singing with an all-girl orchestra. But he could not bring himself to visit Faye Tanner. He was about to board a train in Grand Central Station when it hit him. “It’d be funny if it weren’t so sad,” he later wrote. “I’d just survived World War II, but I couldn’t go to my dead friend’s fiancée like I’d promised her I would.” He feared that he would fall in love with her if he met her face to face. He departed New York on a train for Portland, Oregon, leaving Bernice behind to pursue her singing career.

After a warm reception from his family and friends, Malarkey returned to school at the University of Oregon. Adjusting to peacetime was not easy. He would see and hear things that brought the war rushing back. Young students reminded him of the German sniper, cars backfiring made him duck for cover, nightmares of fighting in the Ardennes woke him, bathed in sweat and tangled in his blankets, and, of course, there were constant images of Doc Roe sitting next to him, informing him of Muck’s death. He could barely look at a picture of the original Easy Company without tearing up.

His relationship with Bernice did not survive the peace, but one night he met and fell in love with a sorority girl named Irene Moor and married her on June 19, 1948. Together they raised four children. Through the years, Malarkey worked as the county commissioner of Clatsop County and sold cars and commercial real estate. And while his nightmares faded, they sometimes revisited him. He went into midwinter funks, thinking about all the friends he had lost. He related in his 2008 memoir, Easy Company Soldier,“December. January. Hate those months. Cold and dark. I still shiver because of the Bulge.” He found refuge in alcohol until he found himself on a suicide drive up Mount Hood. Only an image of his wife stopped him.

Malarkey’s First Easy Company Reunion

In 1980, Malarkey attended his first Easy Company reunion. It had been some 35 years since he had gotten together with his former brothers-in-arms. It overwhelmed him, yet he considered the experience freeing. He wrote Dick Winters after the reunion: “There has hardly been an hour pass since I left France in November 1945 that I have not thought of you and the tremendous officers of the 101st Airborne…. It was without question the proudest and most cherished period of my life.”

He finally connected with Fay Tanner in the 1990s. She had kept the letters he had sent her after Muck’s death. They met at an Easy Company reunion at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. “I put my arm around her and we both broke down and cried,” he later wrote. In 1991 and 2004, he visited Skip’s grave in Hamm, Luxembourg. His first visit included Winters and Carwood Lipton, the company sergeant, and a group led by Stephen Ambrose, so he held back his emotions. On the second visit, however, he went to Muck’s grave alone, reflected on their time together and gave in to the emotions he had suppressed for so long. “I cried 60 years’ worth of tears.”

The Stephen Ambrose book and the HBO miniseries Band of Brothers reminded Malarkey he and his fellow Easy Company veterans had fought the good fight. Oddly enough, he became good friends with Richard Speight, Jr., the actor who portrayed Skip Muck. But he did have some problems with the book and miniseries. He felt the Battles of Carentan and Eindhoven were exaggerated and that his company never saw any German concentration camps. He chafed that his character in the miniseries, played by actor Scott Grimes, portrayed him as from Eugene, Oregon, and that the German prisoner from Portland was killed on D-Day (Malarkey never saw him again and hoped that he survived the war and was living well). But both media highlighted his unit’s exploits and offered him numerous opportunities to reunite and travel with his old friends.

In the 10-part miniseries Malarkey spoke at the beginnings of Episodes 7 and 8 about the fight for Foy and the river crossing in Hagenau, respectively. In each, he struggled emotionally as he spoke of losing friends in combat. When he told about not being able to help wounded friends in an attack, he confessed, “I withstood it well, but I had a lot of trouble in later life because those events would come back and,” he continued as his lower lip tightened, “you never forget them.”

In the Hagenau episode, he related how Eugene Roe asked him if he wanted to see the foxhole where Muck had been killed. He commented, “I said ‘no,’ I wouldn’t be able to stand that, so I didn’t go look at him.” In the follow-up documentary We Stand Alone Together, he spoke about treating Gaurnere and Toye after German artillery blasted off their legs. “I better not talk about it,” he said. “I better not talk about it. Terrible.”

In the end, Donald Malarkey embodied the Shakespearean ideal of “Band of Brothers” from the play Henry V. He trained with young men like himself and developed friendships; he went into combat with them where he performed bravely and those bonds tightened. He suffered, watched his friends die or succumb to the rigors of battle, and he survived, escaping serious physical injury but carrying the mental scars of the friends he lost and the destruction he witnessed.

In his older years Don helped spread the word of his company’s actions, teaching what men can do in the face of violent adversity. The Bard could just as well have been talking about Malarkey’s experience of combat when he wrote Henry V’s speech to his soldiers: “And gentlemen in England now a-bed, shall think themselves accurs’d they were not here, and hold their manhoods cheap while any speaks that fought with us.”

Kevin M. Hymel is a historian for the U.S. Air Force Medical Service and author of Patton’s Photographs: War as He Saw It. He is also a tour guide for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours and leads tours to many of Easy Company’s battlefields in Normandy and Belgium.

This article was updated 1/19/2021

Just got back from Bastogne and have to say it was quite the experience. The best museum in the whole area that I visited was the first one: 101st Airborne Museum. It was hard to imagine the incredible battles that occurred and how much these guys sacrificed. I could never do what guys like Malarkey accomplished.

I would like to point out that the town of Liège is located in Belgium, and not in France as stated in this article.

Thank you for this article about Malark…so well written. I had a friend in Company H…Hank DiCarlo. He talked about the Bulge and the fight for Foy. Again, thank you, and thanks to all the soldiers who took on a fine army of the enemy, and overcame. It is humbling.

Thos. B. Fowler