By Chuck Lyons

In June 1812, the United States, provoked by arrogant British actions on the high seas and its support of hostile Indians in the Northwest Territories, declared war on Great Britain and immediately began planning an invasion of British-held Canada. Four months later, a confused force of some 1,600 U.S. regulars and militia rowed across the Niagara River, landed in Upper Canada, and occupied the 230-foot-high Queenston Heights, setting the stage for what would rapidly become a comedy—or tragedy—of errors.

Prelude to Invasion

Congressional war hawks had long believed that English forces were vulnerable in Canada. Because of the ongoing European war with Napoleon, only a handful of British regulars was available to protect the vast North American possession. In addition, the Canadian provinces were sparsely settled, with a population of only about 500,000 white residents as opposed to the six million people in the United States. Many of the Canadians were located in the Quebec and Montreal areas and were of French descent, with questionable loyalty to the British crown. Others, equally questionable, had American origins. Even worse for the Crown, the Canadian forces that were available—British and Canadian regulars, local militia, and Indian allies—were spread over an 800-mile frontier stretching from Fort Malden, across from Detroit, all the way to Quebec. The straits of Mackinac and Lake Superior were another 300 miles to the west, further stretching the thin British line.

Hoping to strike hard and fast and quickly end the war, American leaders developed a plan for a three-pronged attack against British Canada. Brig. Gen. William Hull was to attack Fort Malden across the river from Detroit, while Maj. Gen. Henry Dearborn hit Kingston on Lake Ontario and Maj. Gen. Stephen Van Rensselaer took Queenston, on the strategic Niagara River north of the falls. An assault on Montreal in Lower Canada also was contemplated, but to attack would require the use of New England militia. The Constitution specified that state militias could only be used to execute U.S. laws, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions. Citing these provisions, the governors of both Massachusetts and Connecticut refused to allow their militias to take part in an invasion of Canada.

Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Isaac Brock, governor of Upper Canada (Ontario) and an experienced British officer, came to believe that an attack on Detroit and Mackinac was essential to secure the alliance of wavering Indians and local militiamen and anchor the frontier’s western end. Brock intended to rely on naval power on the Great Lakes to patrol the frontier between Fort Malden at Detroit and the Niagara River, where he would concentrate whatever forces were available against the main American attack that he believed would come there. “All other attacks will be subordinate or merely made to divert out attention,” he wrote to Lt. Gen. George Provost, commander in chief of all Canadian provinces. “A protracted resistance upon this Frontier will be sure to embarrass their plans materially.”

Defeat in Detroit

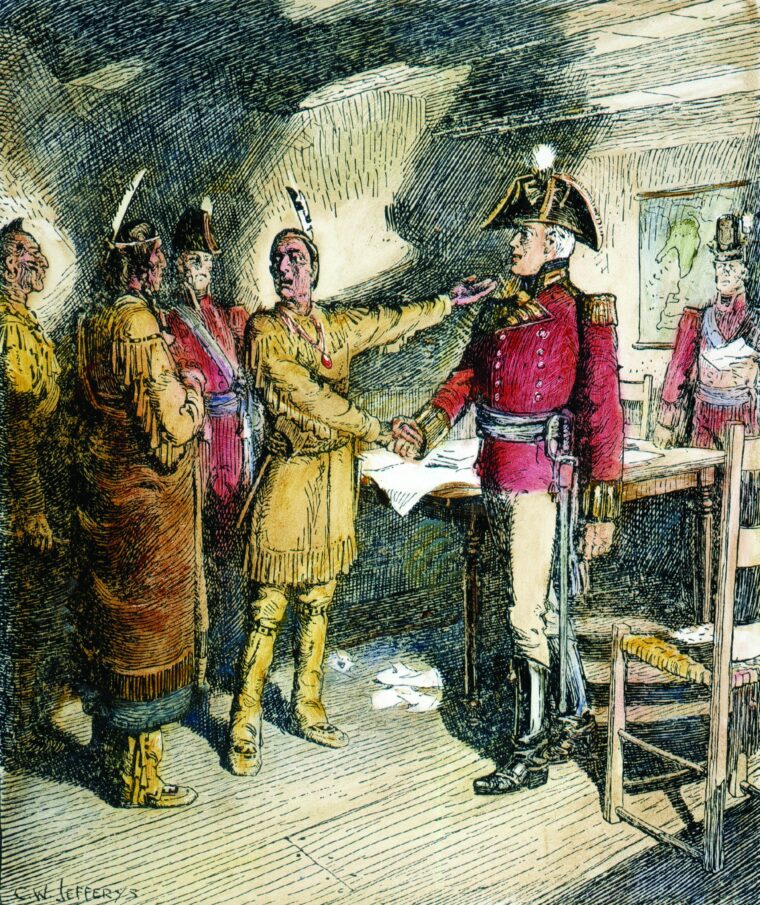

Hull, the governor of Michigan, arrived at Detroit on July 5 with a force of about 2,000 men. At the time, and unknown to Hull, only 100 men of the 41st Regiment, along with 300 militiamen and 150 Indians, defended Fort Malden. While Hull dithered and delayed at Detroit, worrying about his supply lines through Ohio and along the Lake Erie shore, he received news that the American base at Mackinac had fallen to the British on July 17. Meanwhile, Brock had been moving to strengthen the garrison at Fort Malden, sending 60 men ahead in late July and then going to the fort himself with 300 men in August. Once there, Brock met with the Shawnee chief Tecumseh and strengthened his ties with his Indian allies. By mid-August, Brock reported to Provost that he had 300 regulars, 600 militiamen, and about 600 Indians under his command at Fort Malden.

On August 15, Brock demanded Hull’s surrender of Detroit. Using rudimentary psychological warfare, Brock maintained to his counterpart that “you must be aware that the numerous bodies of Indians who attached themselves to my troops will be beyond control once the contest commences.” Brock also let fall into American hands a false document saying that he had 5,000 Indians under his command, leading Hull to believe that the British force opposing him was much larger (and more savage) than it actually was.

Hull at first rejected the surrender demand, and Brock’s land-based artillery, accompanied by the gunboats Queen Charlotte and General Hunter, began a bombardment of the city. Finally persuaded by Hill’s ruses and the subsequent bombardment that he was greatly outnumbered and fearing an Indian massacre of his men and the civilians huddling in the fort—including Hull’s own daughter and her two children—Hull surrendered on August 16. The surrender at Detroit was greeted with shock throughout the United States, and Hull was believed by many to have sold out his country. Two years later, he was court-martialed for his involvement in the fiasco at Detroit, tried for cowardice, and condemned to death. Because of Hull’s honorable service in the Revolutionary War, President James Madison remitted the penalty.

When news of his victory at Detroit reached London several weeks later, Brock was immediately knighted by a grateful King George III. Meanwhile, not resting on his laurels, Brock hurried back to the Niagara frontier to prepare for another American attack. The Niagara River was crossable below the falls from just north of Queenston to just south of Chippewa, a considerable stretch that had to be protected by Brock’s limited forces. He knew that his best chance to do so was to detect any attack quickly and move to meet it while keeping the full American force from crossing.

Van Rensselaer’s Grab-Bag Army

Brock had no way of knowing it, but the American commanders he faced at Niagara had spent most of their time arguing with one another. Van Rensselaer commanded a polyglot force comprising five regiments of New York militia that had been called into federal service in April and several companies of regulars—two from the 6th Infantry, a veteran regiment; two companies of the 13th Infantry; and three companies of the 23rd Infantry. A light artillery regiment provided another 40 men who would fight as infantry, while two companies of the 2nd Artillery, recruited in January, would man the batteries firing from the American shore.

The majority of his officers, like Van Rensselaer himself, were political appointees and were as new to warfare as the men they commanded. Van Rensselaer had never led troops in battle and had in fact opposed the war. At the time, he owned perhaps more land than any other man in the country and was a leader in forming public opinion in upstate New York. He also was considered a likely Federalist candidate to oppose New York Governor Daniel Tompkins for that office. Van Rensselaer managed to secure the services of his second cousin, Lt. Col. Solomon Van Rensselaer, the adjutant general of the state and an experienced military commander, as his aide-de-camp.

Meanwhile, Dearborn was forming his army for an attack directly north at Greenbush across the Hudson River from Albany, gathering raw recruits as they signed up in New England and the Middle Atlantic states and training them at Greenbush. It was a grab-bag army imbued with the republicanism of the new nation and troubled by many of the same problems that plagued Van Rensselaer’s force. Desertion was an ongoing evil, and captured deserters were made to run a gauntlet of their fellow soldiers armed with tree branches while a band played a mocking march. Afterward, the culprits were restored to good standing. Duels were frequent between officers and even enlisted men. Many of the army’s officers were elected by the men and, as a result, were on familiar terms with them, sometimes obsequiously so. One officer complained that his fellow officers were “too democratic in their intercourse.”

In September, Dearborn moved his force north to Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain, near the Canadian border, where he was joined by seven regiments of regular troops, all of which were understrength, and the entire Vermont militia. Few of his top officers, as with Van Rensselaer, were regulars, most having received political appointments. While Dearborn prepared to invade Canada and worried about the 5,000 Canadian militiamen and volunteers gathering to oppose him, Van Rensselaer unexpectedly acted with decisiveness, if not indeed rashness.

Feeling public pressure to attack Canada and erase the disgraceful surrender at Detroit, Van Rensselaer set October 11 as the date for the Canadian invasion and moved on the Niagara River leading a force of 6,000 regulars, volunteers and militia, as well as another smaller force under the command of Brig. Gen. Alexander Smyth, inspector general of the regular army. Van Rensselaer feared that he would not be able to hold his volunteer and militia forces in place once cold weather hit; he wanted to press them into action as soon as possible. If the British barracks at Fort George, near the mouth of the Niagara River, could be captured, Van Rensselaer believed it would provide more comfortable winter billets and help keep the militia in the field.

Problems arose almost immediately. Smyth, a regular army officer, was openly contemptuous of Van Rensselaer. He refused to report to him or attend councils called by the general, and likewise he refused to obey Van Rensselaer’s orders. Rather than deploy his men as ordered near Lewiston, across the river from Queenston, Smyth instead placed his 1,650 men near Buffalo. He then wrote to Van Rensselaer that “the conclusions I have drawn as to the interests of the service have determined me to stop at this place” and went on to advise Van Rensselaer, his commanding officer, where the attack on Canada should take place.

Van Rensselaer had planned for Smyth to attack Fort George from the rear while the main force attacked the high bluffs of Queenston Heights. Rather than delay the attack, Van Rensselaer altered his plans to proceed without Smyth. Almost immediately, something went wrong. As the American army formed on the east shore of the river on the morning of October 11 preparatory to the attack, one of the lead boatmen, either from treachery or simple error, rowed away on the boat containing all the oars needed for the other 13 boats to cross the river, thus making the crossing impossible. The militia troops, grumbling, returned to camp.

Brock, who had hurried back from Detroit with 1,900 men under arms—British regulars, militia, and Indians—hoped to cross the river himself. He planned to attack the Americans and seize a large hunk of New York State, a plan that had been vetoed by the more cautious Provost, who in fact had negotiated an armistice during the summer that allowed both sides to use the Niagara River. By the time the armistice ended on September 1, Van Rensselaer’s troops were considerably better supplied than they would have been had the armistice not been arranged, a fact that understandably angered Brock.

The Battle of Queenston Heights

Having gotten wind of the halting American preparations, Brock expected the American attack to come on the night October 12-13 and hit his headquarters at Fort George. In anticipation of such an attack, he had stationed 1,000 crack British troops there and waited for the Americans to strike.

The American river crossing was planned for a place where the river was about 250 yards wide and the boats to be used were to carry 20 men each. It was determined that 30 such boats were needed for the crossing, but on October 13 only 12 were available to ferry the planned 4,000-man invasion force. It was clear that the men would have to be taken across in shifts, the boats delivering one contingent and coming back to get another. In addition, the boats were too small to carry any of the Americans’ artillery. Before sunrise, 200 American troops led by Solomon Van Rensselaer crossed the river in a rainstorm and were landing on the Canadian side when a British sentry discovered them and gave the alarm. Men of the British 49th Regiment and militiamen from York and Lincoln counties began contesting the landing, and Brock’s artillery, under Captain James Dennis, opened up on the boats ferrying the men across the river.

Awakened at 4 am by sounds of firing seven miles upriver from Fort George, Brock hurried toward Queenston unsure if he was hearing the main American attack or merely a feint that would be followed by an attack against the fort. Along the way he passed captured American troops being herded to Fort George under guard. “The road was lined with miserable wretches,” wrote one of his subordinate officers, “suffering under wounds of all descriptions, and crawling to out houses for protection and comfort.”

As soon as his boat had scraped the Canadian shore, Colonel Van Rensselaer had jumped out and almost immediately was hit by a musket ball. He continued to rally his men and was hit five more times, knocking him out of action. Meanwhile, a boat containing Lt. Col. John Chrystie, the next senior officer under Van Rensselaer, had become disoriented during the crossing, perhaps when the boat crew panicked, and drifted out of the action. Chrystie eventually made it to the Canadian side of the river, but only after a foothold had been established. Van Rensselaer and other officers later blamed him for the American defeat and accused him of cowardice in the face of the enemy.

Van Rensselaer’s wounds and Chrystie’s absence left 25-year-old Captain John E. Wool in charge on the beach, and he was able to break the British resistance to the landing and secure a beachhead. Wool then turned his attention to a British 18-pounder firing on the Americans still crossing the river. The 18-pounder was in a redan on the 230-foot-high Queenston Heights. Wool led his men up the heights by means of a steep fisherman’s path that the British, believing impassable, had left unguarded. The Americans advanced laboriously, often pulling themselves along by grasping rocks and bushes. Brock himself had also arrived at the redan and, unaware that the Americans were behind and above him, had begun correcting the fire of the 18-pounder

British Counter-Attacks

When the Americans attacked, Brock was driven back from the gun along with the gun’s defenders, who were able to quickly spike the gun as they retreated. Brock then rallied the defenders and launched an attack to recapture the position, but it was repulsed by the Americans after a tough fight. Brock was wounded in the hand but nonetheless continued rallying his men for another attack when he was hit by a musket ball in the chest and killed instantly. Brock’s aide, Lt. Col. John Macdonell, a lawyer and politician, took over command and led another charge against Wool’s position. According to legend, he was riding “Alfred,” Brock’s horse, during the attack.

Following Brock’s death, there was a lull in the fighting, and by 2 pm, several hundred Americans were on the Canadian side of the river. By this time, Lt. Col. Winfield Scott, who like Wool was later to gain fame in the Mexican War, had taken over command of the Americans. Scott had been among Smyth’s men at Buffalo when he learned of the impending attack. Without seeking Smyth’s permission, Scott had broken camp and led his regiment through a stormy night to join Van Rensselaer. Brig. Gen. William Wadsworth of New York, a large landowner and politically appointed officer, had happily handed over command to Scott.

Before he was killed, Brock had ordered Maj. Gen. Roger Sheaffe, who commanded the garrison at Fort George, to hasten from the fort with all available men. By this time, Sheaffe was approaching with about 1,000 men and a party of allied Indians. Van Rensselaer, meanwhile, was trying to rally his troops and get as many Americans as possible across the river. The militia troops, however, seeing the nature of the fighting across the river and the wounded being carried back across, refused outright to attack, claiming that they had signed on to fight only in New York State. The Constitution, they argued, proscribed their service outside the United States without their permission. Smyth, likewise, remained at Buffalo with the bulk of the regular troops and took no part in the action. “I found that at the very moment when complete victory was in our hands,” Van Rensselaer later wrote, “the ardor of the unengaged troops had entirely subsided. All I could do was send a fresh supply of cartridges.” The American troops already on the Canadian side of the river were on their own.

Scott, an experienced officer with the 2nd Artillery, was working with a group of about 350 men trying to repair the captured 18-pounder when, at 4 pm, the group was attacked by Sheaffe and his reinforcements. Sheaffe, a loyal British subject who had been born in Boston, had followed Brock’s orders, gathering British regulars, some companies of Canadian militia, field artillery, and a number of Mohawk Indians, all of whom were anxious to avenge Brock’s death. He had led the force on a flanking march up the escarpment and hit the Americans unexpectedly from the inland side. The Indians led the attack, their screams unnerving the raw Americans, many of whom slipped away to hide in the rocks and woods. British regulars and Canadian militia followed the Indians into the fight, firing a heavy volley and then attacking with bayonets at the ready.

What American resistance there was quickly evaporated, and the survivors ran down the heights to join about 250 men on the beach. Getting word of Sheaffe’s approach, Van Rensselaer had ordered the boats to return to Canadian soil to rescue the troops on the west side of the river, but his boatmen refused to do even that.

Wadsworth, realizing he was in a hopeless position, sent Sheaffe a white flag, but the bearer was cut down by the Indians and was unable to make it to Sheaffe. Scott, meanwhile, worried (with good reason) that the Indians would massacre his men, forced his way into the village with a white flag attached to his sword and surrendered. The Indians might have killed him, too, had not two Canadian officers intervened. After surrendering his sword, Scott was shocked to see a large number of American militiamen come out of hiding and surrender as well. The Americans had suffered 100 dead, 300 wounded, and another 925 men captured, including Scott, Wadsworth, four other lieutenant colonels, and 67 other officers. Most of the American militiamen were released to go home after giving their word that they would not rejoin the war until they had been exchanged. The captured regulars and officers were marched off to Quebec. British casualties were 14 dead and 77 wounded, including General Brock.

A Third Failed Invasion

Van Rensselaer resigned following the attack, but only after ordering the American troops to fire a salute in honor of Brock when the general was buried three days later at Fort George. (Today, a 150-foot monument stands in Queenston Heights Park in memory of the general.) His aide, Colonel Macdonell, is buried next to the general. A smaller monument, a bronze statue in a glass case, stands in the village near the cairn marking the place where Brock fell; it commemorates “Alfred,” Brock’s horse, which both officers had ridden to their deaths.

Scott was exchanged the following January, made a full colonel in March, and was promoted to brigadier general a year later. He received the brevet rank of major general the following July. On July 5, 1814, his men, dressed in drab gray homespun uniforms, defeated British forces on the Chippewa River near the mouth of the Niagara River in Ontario. (Today’s West Point cadets wear gray uniforms in memory of that victory.) After the war, Scott fought against the Indians in Florida and the West, took part in the Mexican War, and in 1841 was named commander of the United States Army, a post he held for the next 20 years.

The United States had suffered humiliating defeats at Detroit and at Queenston. Van Rensselaer had resigned. The British had lost Brock—a fine officer—but had secured their Canadian frontier from Mackinac to Niagara. On November 20, following the defeat at Niagara, Dearborn moved his advance guard, commanded by Major Zebulon Pike, across the border into Canada, where some of the regulars mistakenly got into a firefight with members of the New York militia. Shortly after that error had been cleared up, the British attacked with Canadian volunteers and about 300 Mohawk Indians. The ensuing fight was indecisive, but it convinced Dearborn to pull back from the border.

By then, Van Rensselaer had been replaced by Smyth, who wrote to Secretary of War William Eustis: “Give me here a clear stage, men and money, and I will retrieve your affairs or perish.” Refusing to give up the plan of a three-pronged attack, Smyth proposed that his force, called the Army of the Center, join Dearborn and General William Henry Harrison’s army in the west to strike Canada at the same time. Such an attack would have presented severe problems for Provost and the thin line of British defenders. Fortunately for them, the Americans were unable to coordinate Smyth’s proposal, and the general launched a separate attack on Canada on November 28, this time from above the falls.

Smyth believed that Van Rensselaer had made a major error in not having enough boats available to take his full force across the river at one time. Besides dividing his force, Smyth believed it gave the raw militiamen on the American side too much time to think about what they were getting into by entering the boats. Consequently, he made sure to have sufficient boats on hand to carry his full force of 4,000 across the river at once. He would never need them.

Smyth issued a proclamation declaring to his men that the Canadian people were not the enemy. They would soon be American citizens, he said, anticipating an annexation of Canada. The enemy was the British. On November 28, two parties of 200 men each, whose job it was to clear the way for the main army, crossed the river before daylight. They captured and spiked two batteries and damaged but did not destroy a bridge on the road from Chippewa down which any British reinforcements would come. In the action, the two sides came out evenly, with both suffering about 100 casualties and prisoners. If the main American army had continued to move quickly, it might have stood a good chance of success. Smyth delayed, however, demanding the surrender of Fort Erie across from Buffalo. The British refused his demand and were able to take advantage of the delay to recover the captured batteries and repair the Chippewa bridge.

Smyth put off the main invasion several times and, beset as Van Rensselaer had been by widespread sickness in camp and by the continuing reluctance of the militia to fight on Canadian soil, abandoned the plan altogether. Smyth left the army, returned to his native Virginia, and was elected a congressman. Despite his failure at Niagara, Van Rensselaer’s popularity remained high. He was nominated to run against Tompkins for New York governor, a campaign he lost before going on to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Lessons Learned

The Niagara fiasco had shown that a large part of the American population was not in sympathy with the war—at least not with annexing Canada. Niagara also showed that the United States needed a more professional regular army, properly commanded and disciplined, to contest with the British and regular officers. Militia were not to be depended upon in combat, and inexperienced, politically appointed generals were simply not up to the task.

The war itself ground on for two more years. Harrison defeated a combined force of British and Indians in the west, and American troops burned York (the current Toronto) but were unable to take Montreal. America won naval victories in the Atlantic, on Lake Champlain, and on the Great Lakes, and the British attacked and burned Washington, D.C., in retaliation for the attack on York. Treaty negotiations began in 1813 and were settled with the Treaty of Ghent, signed in Belgium on December 24, 1814. General Andrew Jackson, unaware of the treaty, defeated a British force at New Orleans on January 8. The United States Senate ratified the treaty five weeks later.

The treaty did not secure America’s rights on the high seas—a particular bone in its craw—but the end of the Napoleonic wars assured that the British would no longer need to impress American seamen. Indian opposition to American expansion in the Northwest was ended. The nation emerged with a new sense of itself and, equally important, with an army that was more professional, better trained, and better led. It was the army the nation would take into Mexico 30 years later and the army that would provide the backbone for Union hopes in the Civil War 20 years after that. In a way, the United States—however painfully—had come of age on the slopes of Queenston Heights.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments