By Christopher Miskimon

On January 25, 1945, every officer in Company B of the 15th Infantry Regiment of the American 3rd Infantry Division became a casualty in the fight for the “Colmar Pocket” except Lieutenant Audie Murphy. Assuming command, the young Texas native took stock of the day’s fighting. “Our armor pulls ahead of us with gun barrels traversing,” he recalled. “From the woodland comes a crash of shells. Two of the tanks burst into flames. Their escape hatches open and the still living members of the crew bail out. Blazing like torches and screaming horribly, they roll in the snow.”

Despite this horrifying setback, the advance continued, with Murphy leading his company forward into stiff opposition. “As we advance, the fighting develops into individual duels,” he continued. “Once I am pinned behind a tree by a stubborn Kraut using a huge pine tree for cover. Only a few yards separate us. We snipe at one another, but neither of us scores a hit.” His precarious situation ended soon after, when one of his men managed to wound the German, allowing the officer to go in for the kill. “I nail him in the side,” Murphy wrote. “As he drops to his knees, I finish emptying the ammo clip into his body.”

The day’s fighting was difficult because the Germans did not want to give up the Colmar Pocket, holding onto it bitterly with the few troops and armored vehicles they had available. Murphy was like thousands of other American and French soldiers involved in the operation to reduce the pocket and finish the Germans west of the Rhine River. They were doing their duty, but it was not easy.

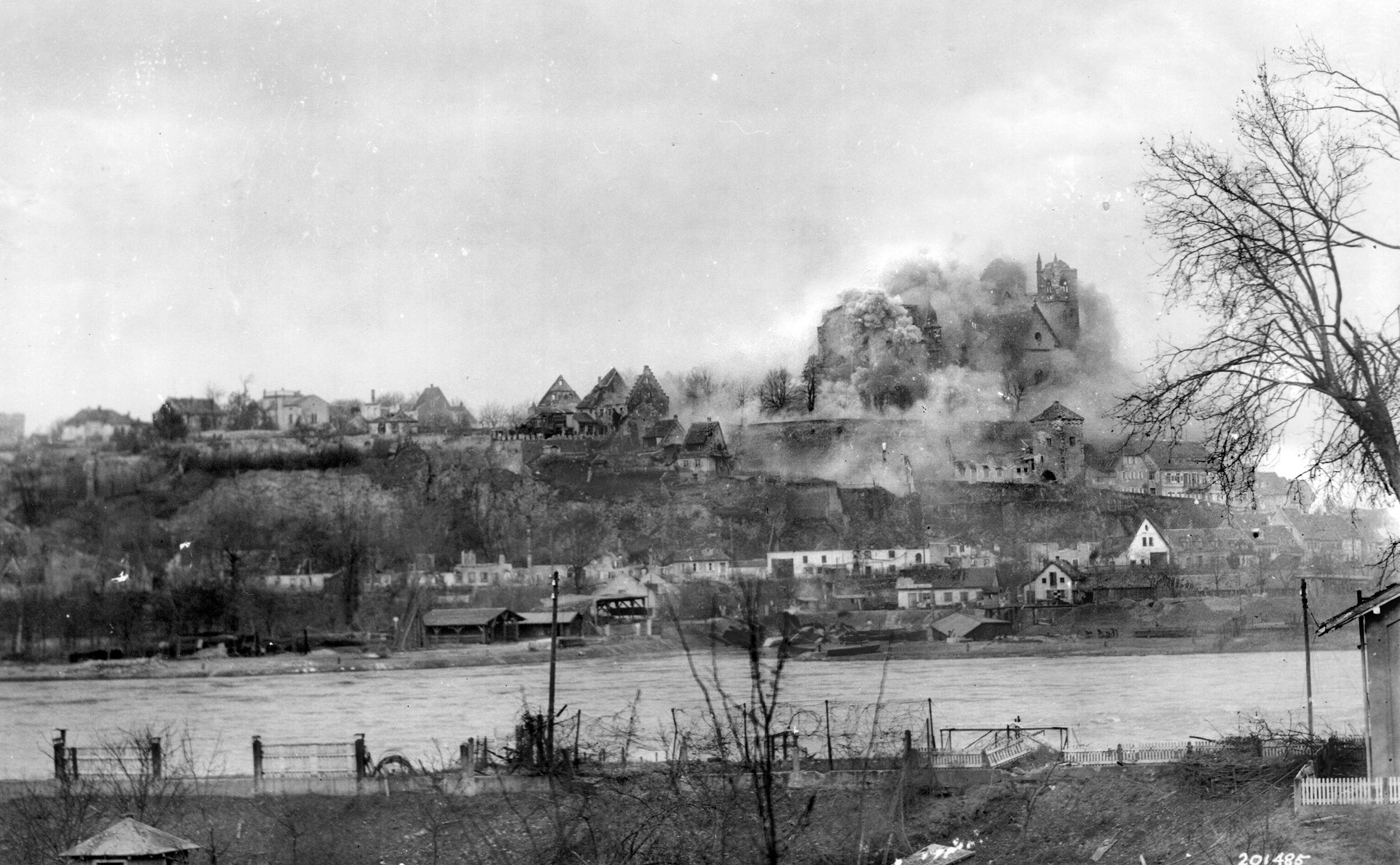

As the German offensive in the Ardennes ended in defeat for the crumbling Third Reich, another fierce battle raged to the south over a similar feature roughly centered on the city of Colmar. This block of territory, consisting of 850 square miles on the west side of the Rhine River, was the Germans’ last piece of French territory.

Capturing this area would shorten Allied lines, allowing them to man the front with fewer soldiers and increase the number of units which could rotate to the rear for rest and reconstitution. A successful attack might also trap thousands of German troops on the west side of the Rhine and compel their surrender. Moreover, a victory would place Allied troops along the west bank of the Rhine to prepare for the eventual crossing of Germany’s last large defensive geographical feature.

The German Nineteenth Army defended the Colmar Pocket with a mix of understrength units that nevertheless had a few veterans in their ranks. The veterans stiffened the units and enabled them to fight the kind of defensive actions required of them at that stage of the war.

Commanded by General of Infantry Siegfried Rasp, the Nineteenth Army consisted of Generalleutnant Max Grimmeiss’ LXIV Corps and Generalleutnant Erich Abraham’s LXIII Corps. Grimmeiss’ corps had two infantry divisions and two volksgrenadier divisions, while Abraham’s division had three infantry divisions.

Rasp also had under his command the 2nd Mountain Division. His armor complement initially consisted of an assault gun battalion and a tank destroyer battalion. The Germans suffered shortages of anti-tank weapons, and although there were plenty of artillery pieces, there was little ammunition for them. They did possess ample small arms ammunition, sufficient food stocks, and good wired radio communications down to the battalion level.

The terrain and weather also assisted in the defense. Much of the region was flat open ground with little cover. Numerous rivers and streams crossed the area, and each village could be made into a strongpoint. One town, Neuf-Brisach, was an old star-shaped fortress town designed by the Sebastien Vauban, the renowned 17th-century French military engineer.

The frigid, snowy winter weather made attacks more difficult, with temperatures hovering around freezing and up to three feet of snow on the ground at the time of the initial Allied attacks. More snow fell over the course of the battle. The defending Germans were mostly able to shelter their troops indoors, a crucial advantage. The attack could possibly have been delayed, but Allied weather forecasters predicted a thaw coming in early February which would turn the area into a muddy quagmire, complicating vehicular movement.

The French 1st Army under General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny assumed responsibility for eliminating the Colmar Pocket. Unfortunately, the French forces were in a weakened state with limited offensive potential.

De Lattre quickly realized that he needed reinforcements to achieve success and only the Americans could provide them. He conferred with his superior, Lt. Gen. Jacob Devers, commanding the U.S. Sixth Army Group. Devers gave him the French 2nd Armored Division and the U.S. 28th Infantry Division, with the possible addition of the U.S. 12th Armored Division if it became available. Since the 28th Infantry Division was badly depleted from fighting in the Ardennes, Devers specified it had to be placed in a defensive position.

De Lattre decided to conduct a double envelopment of the pocket to cut off the Germans and prevent them from escaping across the Rhine. De Lattre knew that the capture of the two remaining bridges over the Rhine were crucial to the success of the attack. At the southern end of the pocket the Neuenburg Bridge sat near the French town of Chalampe. Two miles east of the town of Neuf-Brisach sat the Brisach Railroad Bridge, which withstood so many Allied aerial attacks local German troops awarded it an honorary Iron Cross. The French 1st Army possessed two corps, and de Lattre assigned one to each end of the Colmar Pocket.

General Emile Bethouart’s French I Corps, which comprised two infantry divisions, a mountain division, and an armored division, was responsible for operations on the southern end of the pocket. Bethouart’s corps was a diversionary effort to draw German attention and reserves.

Two French infantry divisions, the 2nd Moroccan and the 4th Moroccan Mountain, with tank support from the French 1st Armored Division, would make the initial attack, anchored to the 9th Colonial Infantry Division along the Ill River.

This assault would cut the local road network after which both divisions would move toward the bridges on the Rhine. De Lattre scheduled the attack for January 20, two days before the main effort, to give the Germans the impression this was actually the main attack and force them to commit their reserves.

Joseph de Goislard de Monsabert’s French II Corps was to go into action on January 22, launching an attack from the north. The II Corps would bypass Colmar and push to Brisach in order to cut off any German retreat. Monsabert’s reinforced corps comprised the French 1st Infantry and 3rd Algerian divisions, as well as the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division. The French 5th Armored Division and U.S. 28th Infantry Division would support the attack. The U.S. 3rd Division received the 254th Infantry Regiment from the 63rd Division as a reinforcement. Extra engineer units were assigned to the operation to assist the Allied divisions in crossing the many rivers and streams in the area. To aid in the effort, logistics staff furnished Bailey bridges to the combat engineers.

Bethouart’s I Corps attacked German forces from the south on the morning of January 20 beginning with a 30-minute artillery bombardment. A snowstorm blanketed the area and made the advance difficult, but the French I Corps soon found a unit boundary between two German divisions and exploited it. German resistance against the French left was weak, but the weather kept the advance slow. The snow piled three feet deep and made roads almost impassable.

The Germans put up a stiffer defense on the French right, and they even mounted a counter-attack. Still, the French units there managed to advance about three miles. Even a frigid river proved no obstacle when the 5th Company of the 23rd Colonial Infantry Regiment jumped off a half hour early. The French soldiers forded the river, braving low temperatures and the threat of frostbite to seize a factory on the far side of the river. The French used this small bridgehead to bring forward engineers to erect foot bridges. Further attacks inflicted heavy casualties on the defending Germans, who lacked effective artillery support. The day ended with a gain of several miles for the French, but they were still short of their initial goal of the town of Ensisheim.

The next day the weather worsened, slowing the French even further. The Germans, taking advantage of their warm quarters, launched several counterattacks supported by a small number of armored vehicles. The French troops, who had spent the previous night shivering in the open, were unable to make any further progress. Rasp requested from Berlin additional armor to defeat the attack, but by and large he was not overly concerned about the situation. The German high command rightly considered the French attack to be a diversion. To shore up the defense, the German high command dispatched a mobile antitank unit and the 106th Panzer Brigade. With the addition of the panzer brigade, Rasp had about 65 tanks and assault guns.

The weather improved substantially on January 22. This allowed the French to resume the offensive. The 9th Colonial Division made some progress, but reached a point where forest surrounded their positions and created concerns about converging German attacks emerging from them. Rather than fall back, the French commander decided to prepare artillery concentrations in case the Germans appeared. This decision proved prudent when an Alsatian deserter appeared that night, claiming a German attack would start at dawn.

The next morning a battalion of German tanks with infantry support appeared. They advanced steadily despite French artillery fire. Fighting raged all morning, but by midday the Germans had withdrawn. German losses in the counterattack consisted of 60 dead and 100 captured. To their credit, the French had knocked out seven German tanks and two armored cars. Further progress over the coming days proved slow due to weather and German resistance.

The northern attack began with the French 1st Infantry Division driving east and protecting the left flank of the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division. De Lattre admired the American unit’s commander, Maj. Gen. John “Iron Mike” O’Daniel, and expected substantial progress from the division.

O’Daniel had devised a plan known as Operation Grandslam in which each American infantry regiment would attack successively. The plan called for the first regiment to attack east, pierce the German lines on the Ill River between Guemar and Ostheim, continue east for several miles and then turn south for another five miles. The next regiment would then take over, driving east for a few more miles before turning south. In this way, O’Daniel hoped to side step his division all the way to the Colmar Canal northeast of Colmar.

Success would open a path for 5th French Armored Division to reach Neuf-Brisach and link up with I Corps.

The attack began at 9 p.m. on January 22 when the U.S. 7th Infantry Regiment advanced without artillery preparation to achieve surprise. The 30th Infantry Regiment followed three hours later. The men of the 7th Regiment’s 1st Battalion, led by Lt. Col. Mackenzie Porter, wore white snowsuits and carried inflatable boats. They quickly crossed a bridge over the Fecht River, but almost lost Porter and his headquarters group to a bouncing mine which luckily did not explode. All the companies rendezvoused on the other side of the Colmar Woods. When the soldiers reached the Ill River, they decided that rather than wait for the engineers they would build a makeshift floating bridge using their inflatable boats. They soon advanced over another stream and kept going.

The rest of II Corps attacked the next morning, January 23. The French 1st Division made satisfactory progress, reaching Illhaeusern, a town at the juncture of the Ill and Fecht Rivers. A Foreign Legion Brigade rushed through the town and seized three intact bridges, including one able to support vehicles. Another Foreign Legion Brigade took over the attack east of the town, but soon ran into stiff German opposition at Moulin. The Germans counterattacked that evening. The German infantry advance with the support of heavy artillery and two tanks. They drove the French back into Illhaeusern. The Germans pursued the retreating French into the town, but ultimately were driven out with heavy losses.

In the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division zone, the 30th Infantry Regiment encountered difficulty around Riedwihr, five miles northeast of Colmar.

The soldiers of Company A hid in some woods when they realized they were dangerously exposed to a nearby German unit, which fortunately did not spot them. Companies C and G were glad to see two platoons of 57mm antitank guns arrive to shore up their position. Engineers worked to strengthen the bridge over the Ill so tanks could get across, but the regiment was ordered to attack and seize the town right away. Soldiers spotted German tanks beyond the woods around the town of Riedwihr and feared attacking without their own armor, but advanced anyway.

The Germans let the Americans get close before opening up with machine guns and tank cannon. The soldiers of companies I and K attacked Holtzwihr and met similar resistance, but when the soldiers of Company I returned fire, they heard angry shouts in English to cease fire. Company K had made it into the village and began setting up a defense. Morale went up when a new soldier used a bazooka to drive off an approaching German tank, which backed away around a corner.

The soldiers’ elation subsided when a German counterattack began 10 minutes later. The fighting became so confused that groups of American soldiers clearing houses ran into German troops doing the same thing. German tanks roamed the area around the towns as the sun went down, and repeated attacks forced the Americans out of the built-up areas and into the surrounding forest.

At the bridge over the Ill, the engineers thought they had reinforced the bridge sufficiently, but when a single Sherman tank moved across to test the span, it collapsed into the shallow river below. The bruised crew evacuated while the other tanks took up supporting positions along the west bank. The American infantry on the east bank set up defenses as the Germans increased the pressure.

The Americans sent out patrols to maintain contact between the different companies and battalions, but they were driven back by the intense firing. Whenever possible, American infantrymen called in artillery fire on the Germans, but with limited effect. Panic started to set in as men struggled between their obligation to fight and the powerful desire to flee and survive.

In many places small numbers of men snuck off for the safety of the rear, but here and there officers and noncommissioned officers took charge. A lieutenant in Company G ordered several sergeants to round up as many men as possible. The lieutenant then led the group to the enemy defenses around one of the crossing points where they entrenched.

Meanwhile, Colonel Lionel McGarr, the commander of the 30th Infantry Regiment, gathered 200 stragglers and retreating men, rallied them, and ordered them to be rearmed and reequipped.

Next, he inspected the entire front line of the 30th Infantry, talking to the men in each foxhole and reorganizing the line to improve it. McGarr did this for five hours, even as tank and machine gun fire rained around him. A ricocheting bullet almost killed him, but he trod on, even arranging for blankets and hot coffee. It would take time, but the 30th Infantry was slowly reorganizing.

Meanwhile, the 15th Infantry Regiment prepared to enter the fight. At 8 p.m. on January 23, O’Daniel ordered the 15th to recapture a bridge near a manor house called Maison Rouge. By 5 a.m. Companies I and K succeeded in retaking the bridge, lost to the earlier German counterat-tack. The Americans tried to entrench, but the couldn’t dig in the frozen ground. The Germans soon returned to reclaim the bridge. Artillery slowed them down, but they soon overran the defending Americans, first I Company and then K. Those American infantrymen not captured retreated toward the west bank of the Ill.

Many took refuge in the Maison Rouge, where they passed around a newly discovered bottle of whiskey. Most believed the Germans would soon arrive and capture them, but one officer resolved to call artillery down on the house if he must. At 9:30 a.m., the situation stabilized when large amounts of U.S. artillery began crashing down on the nearby Germans, disorganizing them and breaking up their attack. Nearby, American engineers finally completed a stout bridge, and American tanks crossed over the Ill.

Early that afternoon, the 1st Battalion of the 15th Infantry Regiment counterattacked and drove the Germans back from the bridge for good. The soldiers even found most of the weapons and equipment abandoned by the 30th Infantry during chaos of the battle. It was gathered up for reissue. Many veteran infantrymen said the fighting was as severe as that they had experienced at Anzio a year earlier.

The 15th Infantry advanced on Riedwihr with armor support on January 25, but it proved slow going, with men advancing tree to tree. They reached the outskirts of the town at 2 a.m. the following day but soon ran out of ammunition. Meanwhile, the attached 254th Infantry moved against Jebsheim.

The Germans counterattacked again on January 26, overrunning several American companies. One of these was Company B of the 15th Infantry Regiment, which was commanded by Murphy.

Over the course of the previous day, Company B had suffered 102 of 120 men killed or wounded without even reaching the town. This left Murphy and 17 men to defend his zone. Against this tiny force came two companies of German infantry backed by six tanks. The woods were sparse with little underbrush. A nearby artillery observer, Lieutenant Walter Weispfenning of the U.S. 39th Field Artillery Battalion watched tanks firing at Murphy and his men as they went past, giving wide berth to a burning American M-10 tank destroyer. The German panzer crews feared it might explode. Weispfenning directed artillery fire while other soldiers fired bazookas at the German vehicles, as about 250 German infantrymen came across a small field at them. Small arms fire flew all around Murphy and his men.

With the Germans only 100 yards away, Murphy climbed onto the burning tank destroyer and manned the .50-caliber machine gun. If the fire reached the gasoline or ammunition, Murphy would be killed in the explosion. Despite the risk, he began firing bursts into the advancing Germans, cutting down many of them. The enemy tanks shot at him, Nazi infantry fired rifles and submachine guns, but Murphy stayed at his exposed position. His well-aimed fire cut down a dozen Germans in a ditch 50 yards away as they tried to outflank him. Bullets ricocheted off the tank destroyer’s hull and two shells struck it, but the young American officer remained in action even as near misses shredded his uniform. The enemy tanks which had earlier passed by returned to support their lagging infantry, pinned due to Murphy’s fire. Even then he stayed atop the tank destroyer, remaining there for an hour despite every German attempt to dislodge him.

“The German infantrymen got within 10 yards of the lieutenant, who killed them in the draws, in the meadows, in the woods—wherever he saw them,” recalled Sergeant Elmer Brawley.

Brawley believed Murphy must have hit at least 35 enemy soldiers, despite being covered in soot and surrounded by smoke which obscured his vision. It turned out, though, that he had actually struck as many as 50 enemy soldiers. Eventually a round hit him in the leg, but still he refused to take cover or leave his gun. His fire caused the entire German attack to falter, as German troops fell back, and with the loss of their supporting infantry, the tanks withdrew as well.

With his ammunition expended, Murphy climbed down from the tank destroyer’s engine deck, went over to his men, and organized them for a counterattack. He refused any medical aid as he led his men on their unexpected assault, forcing the Germans back. Murphy even called in additional artillery fire on the retreating enemy.

His actions completely stopped the German attempt to take the American-held woods and kept his company from being encircled, killed, or captured. He only agreed to medical attention after his mission was complete. For his bravery and determination, Murphy would later be awarded the Medal of Honor.

While the U.S. 15th and 30th infantry regiments fought around Riedwihr, the 7th Infantry Regiment made progress toward Colmar. The 1st Battalion got the job to seize a manor house called the Chateau de Schoppenwihr, a large stone structure with outbuildings surrounded by a seven-foot-high stone wall.

The plan was to send Company A in from the north with tank support while companies B and C attacked from some woods to the east. As Company A moved down a road to the chateau, its GIs ran into some soldiers in white camouflage.

One of the GIs went forward to identify them, thinking they were other Americans supposed to be in the area. When he asked whether they were American soldiers, the white-clad men leapt into foxholes and trenches and opened fire.

The Americans hit the ground as German rifle and machine gun fire started up. Within a few minutes, however, a Sherman tank rumbled down the road. Its cannon barked and its machine guns chattered, killing several Germans and setting fire to a haystack. As other German troops got up to retreat, they were silhouetted against the flames enabling the Americans to shoot them down. More fire came from the chateau, so the men of Company A took cover in some nearby woods, still protected by the friendly tank.

With A Company out of action for the moment, companies B and C took over the assault after a heavy artillery barrage, Company B in the front and Company C following behind.

Company B’s 1st Platoon lead the way, but when they were about 200 yards from the stone wall a group of Germans opened fire from the far side of a raised road with machine guns and rifle grenades. A German tank appeared 150 yards to the south and added its fire to the battle as well.

The company commander realized his men were trapped in the open and there was nowhere to go but forward. He led them ahead even under the heavy fire until they reached the near side of the raised road. They could hear the Germans on the other side, 20 yards away. C Company also took casualties and pulled back to the woods.

Even with the cover of the road bank, Company B was in trouble. Grenades came sailing through the air at them and the tank still had a clear field of fire. A soldier fired a few rifle grenades at the looming armored vehicle but was hit and killed moments later. Casualties began to mount, so Lieutannt Richard Kerr decided to keep going forward. As he started across the road, he shouted for his soldiers to follow him.

Many men got up and followed him, screaming and firing. The shocked Germans lost their morale; many surrendered, but some had to be killed by grenades tossed into their foxholes. The GIs kept going until they cleared the perimeter defenses and arrived at the stone wall. Two bazooka teams worked their way around the panzer and drove it away. The American artillery barrage had blown several holes in the wall, so Company B went through and attacked the chateau. There was little resistance, and it was soon in American hands. Rumors spread that Heinrich Himmler had recently stayed in the house, so the victorious GIs wanted to see its opulence for themselves and maybe even grab a few souvenirs.

At Jebsheim, the 254th Infantry found the going rough. Four artillery battalions shelled the town at 2:45 a.m. on January 26 just before the regiment’s 1st and 2nd battalions attacked.

Despite the preparation, the Germans repulsed the American infantry assault. During their attack, the GIs came under heavy fire from Jebsheim Woods. The 3rd Battalion went into the woods and cleared it out in a day and a half of fighting. Meanwhile, the attack on the town was renewed, this time with eight battalions of artillery in support. It took three days to clear the town, with help from the French 5th Armored and 1st Infantry Divisions, and cost 600 dead.

On January 27 the two reconstituted battalions from the 30th Infantry Regiment joined a French armored unit, passed through the lines of the 15th Infantry, and took the crossings of the east-west Colmar Canal, between the Ill River and Muntzenheim. The pressure began to mount on the Germans, but they could do little to improve their situation other than hold on and try to exact a high toll on their opponents.

By that time the French were running low on infantry, and the weather remained difficult. De Lattre voiced his concerns to Devers, who had received five new American divisions along with support troops. Devers ordered the U.S. XXI Corps to go into action between the two French corps. It took charge of the battle-weary U.S. 3rd and 28th infantry divisions along with the newly arrived U.S. 75th Infantry Division and, backed by the French 5th Armored Division, were slated to attack towards Neuf-Brisach and capture the bridges over the Rhine.

The XXI Corps took control of its assigned zone on the morning of January 28 and attacked toward Neuf-Brisach the next day. The 3rd Infantry Division acted as the main effort, attacking across the Colmar Canal. The 28th Infantry Division would carry out demonstrations and raids to keep the enemy’s attention and be ready to exploit any German withdrawals. The French 5th Armored would attack in several columns when ordered, and the newly arrived 75th Division was still assembling its regiments but would follow by January 30. The assault across the Colmar Canal met little resistance, though it took another day to get tanks across. The 3rd Infantry Division made good progress, even repulsing a German counterattack on January 30 and clearing Muntzenheim.

The 7th Infantry Regiment, relieved by a regiment from the 75th Infantry Division on the night of January 30, advanced to take Horbourg, a suburb west of Colmar. If the Americans could seize the town, they would succeed in closing the last German escape route west of Colmar. The 2nd Battalion of the 7th Infantry, down to 30 men each in its rifle companies, led the way. The battalion commander, Major Jack Duncan, approached a nearby French armored unit to enlist their aid but they refused. Disgusted by the lack of French cooperation, Duncan prepared his men to attack at 9 p.m. As the American infantrymen moved out, Company E led the way supported by two tanks.

When the soldiers were 20 yards from the edge of the town, German machine guns opened fire, wounding five men and driving the rest to the ground, crawling forward.

One of the Sherman tanks blasted the house containing the machine guns, so the Germans moved to another. The tank crew soon destroyed that one as well. The Company E men quickly occupied the first house and covered a platoon as it took the second. The Germans fled, abandoning their machine gun, but an antitank gun opened fire, forcing the American tank to take cover. When they tried to outflank the Germans, the Sherman rumbled into a tank trap and was disabled. Fortunately, when the second tank arrived, the Germans retreated.

The Americans continued up the street with the tank methodically firing into houses as they advanced. They used small arms and grenades to clear the houses on both sides of the street. This gave them a foothold in Horbourg, but German infantry armed with antitank guns and panzerfausts counterattacked. The Americans took cover in the houses for the night, and in the morning mortar fire pounded them. Still, they managed to fight off another German attack. In the early afternoon the French armor finally joined the fight and advanced with the Americans.

The combined Franco-American assault force shattered the German defense, killing 40 and capturing 70 prisoners. Sporadic fighting continued into the night until 11 p.m. when the 289th Infantry from the 75th Infantry Division took over. Further German efforts to retake the town and keep their escape route open were defeated. More French tanks appeared and Horbourg was in Allied hands by January 31.

On February 1 more American infantry supported by French tanks reached the Rhine-Rhone Canal, just a few miles west of the Rhine River. By evening the 3rd Division’s lead regiments were only a mile from Neuf-Brisach and two miles from the Rhine. Antiaircraft units covered the troop’s advance, firing 22,000 rounds of .50 caliber ammunition. When two German tank destroyers blocked the 7th Infantry’s advance, Private Joseph Duncan knocked one out with his bazooka at 500 feet. The other quickly withdrew. American artillery fire repulsed several small German counterattacks.

Another act of courage took place in the early hours of February 2. As American infantry entered the town of Biesheim a large German force attacked, forcing the GIs to take cover in some nearby ditches, which turned out to be full of German soldiers. Fierce hand-to-hand combat followed. Technician Fifth Grade Forrest Peden, a forward observer from the U.S. 10th Field Artillery Battalion, gave aid to two wounded soldiers while under enemy fire. Discovering his radio inoperable, he ran 800 yards through more enemy fire to reach a battalion command post.

Once there he saw two light tanks. He climbed aboard one of them to show them the way to the ditches where the wounded soldiers were located. As the two tanks reached the ditches, the one carrying Peden was struck by enemy fire, which killed Peden. For his valor, Peden posthumously received the Medal of Honor.

The moment arrived to take the town of Colmar. The 28th Division attacked and by the morning of February 2 arrived at the northern gates of Colmar despite heavy resistance. The French 5th Armored was allowed to enter the city first, and after being greeted by the citizens, the division split into three columns. One moved west to guard against an attack from the Germans in the Vosges, the second went south of the city to block the approaches there, while the third stayed in the city to help the Americans clear the town.

On February 2 the Germans began to fall back all along the line, most of them trying to get over the Rhine to safety. The road through Rouffach to the south of Colmar was the last place for the Germans in the Vosges to get away, so XXI Corps started to push south to cut them off and link up with French I Corps, still pushing north. The corps received the U.S. 12th Armored Division to help with this effort. Combat Command B of the 12th Infantry attacked on February 3 and made some progress before one of its columns was stopped. The 28th Infantry Division took over their positions while Combat Command A attacked, getting held up by antitank guns for a day before seizing the town of Hattstatt.

Just before dawn on February 5, the Americans reached the northern edge of Rouffach. The 2nd Platoon of Company D, 43rd Tank Battalion, found a roadblock, so platoon leader, Lieutenant Charles Ippolito, went ahead on foot to scout for German defenses before attacking. Civilians told him most of the Germans were gone, except for some troops ready to destroy the bridges east of town and a pair of tanks just east of the bridges at a north-south rail line. Ippolito’s superior ordered another tank platoon to flank around, knock out the German tanks, and block the escape of any retreating Germans. He also summoned more infantry to help clear Rouffach, unsure whether there were more Germans hiding in the town.

More civilians reported a French force nearby, but this turned out to be a relatively weak scouting force. Ippolito ordered one of his tanks to ram the roadblock, but the tank wound up going over the roadblock and coming down intact on the other side. The Americans used a towing cable to tear it down. After cutting off other avenues of escape the Americans entered the town, warily probing forward. All this caution was for naught given that nearly all of the Germans had withdrawn. They soon stumbled upon a French reconnaissance unit from the French I Corps. The two corps had rendezvoused and blocked the Germans’ last avenue of escape, leaving elements of four German divisions cut off.

All that remained was Neuf-Brisach, so XXI Corps moved toward it. German resistance by that time was negligible. By the morning of February 6, the 7th Infantry Regiment had sealed off the town. Patrols from the 30th Regiment probed around the town, which was surrounded by its high walls. Getting into the city could prove difficult if the Germans put up a fight, but few Germans were found outside the town. At 9:30 a.m. a platoon patrolling along the Rhine-Rhone Canal met a French civilian, who showed them a dry moat leading to a 60-foot tunnel leading right into the city. Within two hours the city was secure, with 65 more enemy troops captured.

The Allies had destroyed or captured all of the German units west of the Rhine by the morning of February 9. In 20 days of fighting, the French suffered 13,000 casualties, and the Americans suffered another 8,000 casualties. In contrast, the Germans lost 25,000 troops.

The offensive to destroy the Colmar Pocket succeeded, despite several setbacks, such as the slow progress of French I Corps and the hard fighting at Riedwihr. That a Franco-American force had won the victory made it an even brighter achievement. Nevertheless, de Lattre’s force emerged from the operation weakened due to its inability to replenish its infantry. With the Colmar Pocket eliminated, the Allies could focus exclusively on crossing the Rhine and advancing deep into the heart of Germany.

A little editing is called for. You have repeated several paragraphs starting at :

“The combined Franco-American assault force shattered the German defense,….” and so forth.

Thanks for the alert proof reading. Something odd happened when the story was moved from the magazine print files, to the website.