By Allyn Vannoy

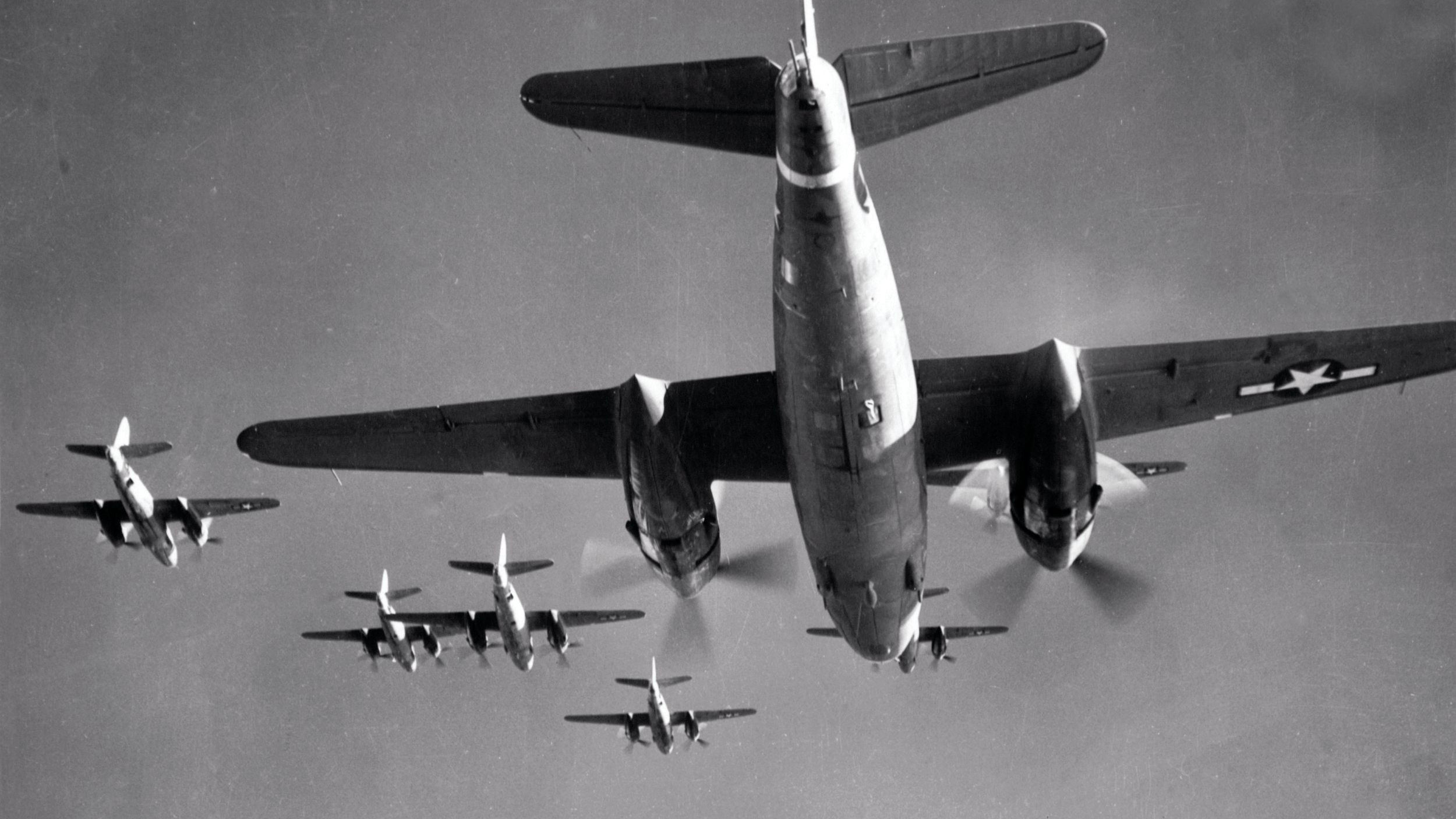

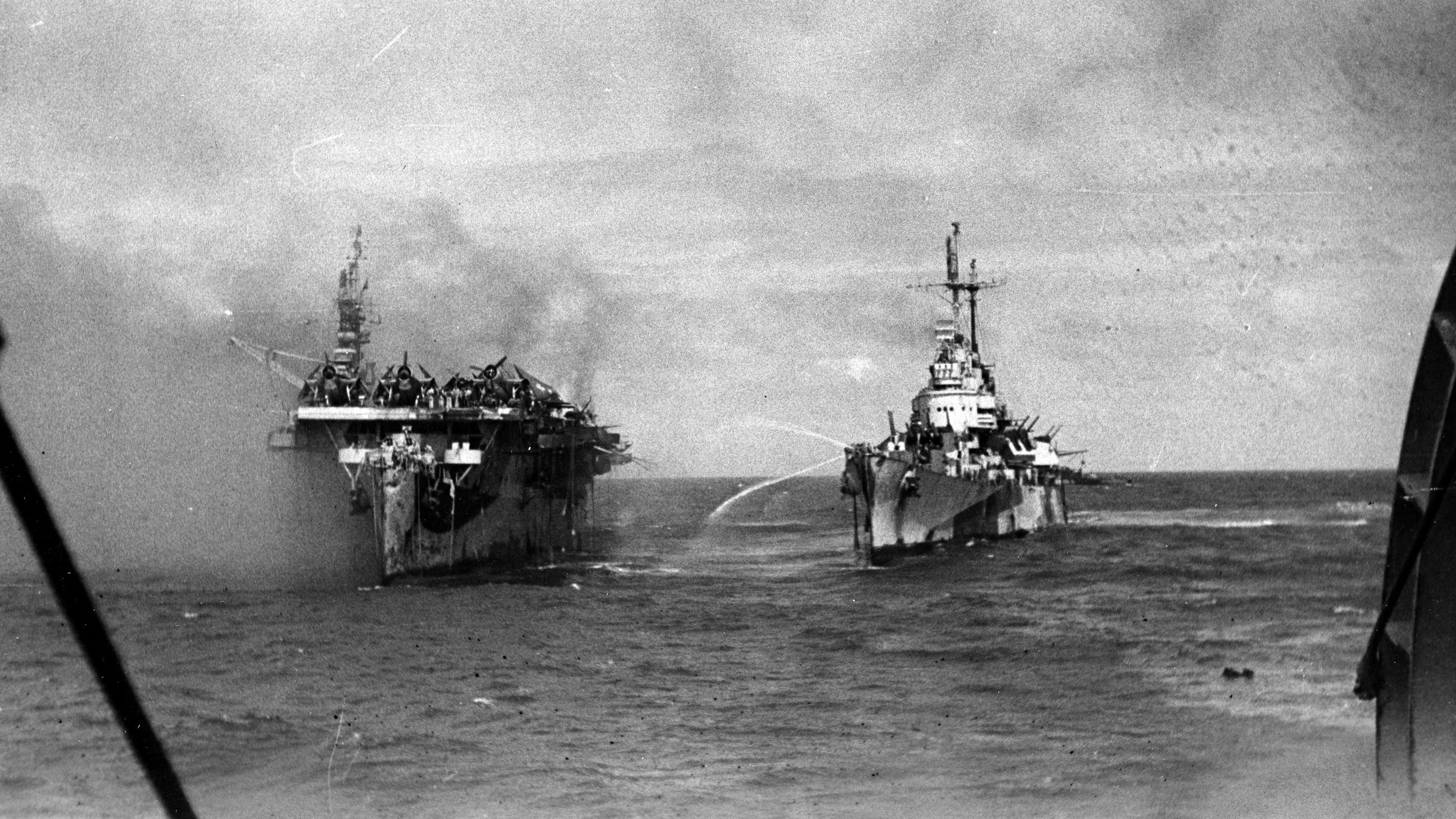

During the Allied air campaign against the Third Reich in World War II, well over a million tons of bombs were dropped on German territory, killing nearly 300,000 civilians and wounding another 780,000. While much of the focus remains on the air battles above Germany—the Anglo-American bombing offensive and the defeat of the Luftwaffe—the role of German flak units has generally been ignored, despite the employment of more than one million men and women who helped bring down more than half of all Allied aircraft.

As the effectiveness of the Luftwaffe’s fighter defensive against Allied bombers failed, flak forces began to shoulder a greater portion of the load as the main element of home air defense. German antiaircraft concentrations around key targets grew dramatically. Prior to January 1944, fighters claimed the lion’s share of downed U.S. bombers, but in June 1944, flak downed 201 Eighth Air Force heavy bombers while fighters claimed only 80.

Allied strategic bombing forced Germany to organize an extensive air-defense system of both air and ground elements. The defense system included concrete towers over 100 feet high that allowed heavy antiaircraft guns to be sited above the surrounding buildings, the creation of camouflaged streets, and even false towns. A network of air-warning, coordination, and direction centers detected Allied bombers and alerted thousands of antiaircraft gunners, searchlight units, and civilian defense authorities to the approaching waves of bombers.

Allied bombers had to penetrate belts of heavy antiaircraft guns spread across the Reich’s frontier and along routes of approach to target areas. A target might be defended by anti-aircraft guns with barrage balloons overhead, an array of searchlights, and even smoke pots to obscure the area during daylight. Low-level raids had to run gauntlets of rapid-firing 20mm and 37mm guns.

After the start of the war, the Luftwaffe quickly realized the need for protecting Germany and occupied territories from the growing strength of Allied bombers. The result was an enormous expansion of the antiaircraft artillery organization. Total antiaircraft artillery personnel strength, including staffs and administration, grew to over one million, with hardware that included 9,000 heavy guns, 30,000 light guns, and 15,000 heavy searchlights.

The basic German air defense was called Flakartillerie, or flak, for short. It was part of the Luftwaffe, under control of the Air Ministry, the exception being Heeresflak—army antiaircraft. The chief of the Luftwaffe was responsible for the air defense of Germany and important areas of occupied countries. This responsibility was carried out through air-territorial districts (Luftgrue) and special defense commands, which contained aviation assets, antiaircraft artillery with searchlights and barrage balloons, and necessary aircraft-warning service units. The flak command in an air district was divided into Flakgruppen, which in turn were divided into subgroups called Flakuntergruppen, which operated sector controls.

The sector controls were the operational headquarters for fire control and also acted as communication centers. Close liaison was maintained between the flak organizations and the warning service, and between flak and fighter-intercepter units. Operational units included battalions and regiments. Organization of the individual units was not uniform; the exact composition of the unit depended upon the role it was expected to play in the defense scheme. Regiments might consist entirely of searchlight units, gun units, or mixed gun and searchlight battalions.

A heavy flak battery was equipped with four to six heavy guns, usually 88mm, and two light 20mm guns for close-in protection of the battery. Light flak batteries were usually equipped with about a dozen 20mm or 37mm guns. Static guns were placed on permanent mounts or in fixed positions, often with living quarters for the crews. Calibers of static guns ranged from light 20mm to heavy 150mm guns. Light- and medium-caliber guns could be mounted on the tops of buildings and factories.

Guns in static roles were also emplaced in towers. In Berlin, there were three 100-foot-high concrete towers, each with a roof area of 250 square feet and equipped with four heavy antiaircraft guns. Mobile guns were mounted on railway cars, allowing positions to be altered at short notice. The Germans believed that air defenses needed to be flexible and that active defense should be closely coordinated with deception. Under this system, different positions were occupied by mobile units at different times, and antiaircraft defenses were changed frequently to meet changes in enemy air tactics and confuse Allied planners.

In well-defended areas, heavy guns were deployed on the outskirts with special attention to expected lines of approach. Light guns were concentrated at vulnerable points, such as factories and docks. They were occasionally emplaced on lines of approach, such as canals, rivers, or arterial roads. In an effort to counter strafing operations, light guns were used to ambush fight-bombers.

Several types of fire-control methods were employed for heavy antiaircraft guns. Because there were times when the target was not seen, or when for various reasons it was not practicable to rely on fire directed at only one aerial target, the Germans used several methods of fire control, including sighted and unsighted targets, predicted concentrations, and fixed barrages. Guns might fire individually, or in salvos of as many as 32 guns.

Fixed barrages were used early in the war. Controlled by a central operations room, the fire could be laid in almost any shape—screen, box, cylinder, or in depth. This type of barrage was usually thrown over a vulnerable target point or just outside a bomb release point, mostly at night or under conditions of bad visibility.

Light or medium antiaircraft guns were highly maneuverable and could engage a target almost immediately as it came within view and range. These guns relied on high rates and volumes of fire. For altitudes below 1,500 feet, they were exceedingly accurate. At very low levels, about 50 feet, accuracy was considerably reduced owing to the limited field of view, the restricted time of engagement, and the high angular velocity of the target in relation to the guns. Fire from light and medium guns was directed and corrected by observation of tracers. Guns were sometimes sited close to a heavy searchlight to obtain approximate target data.

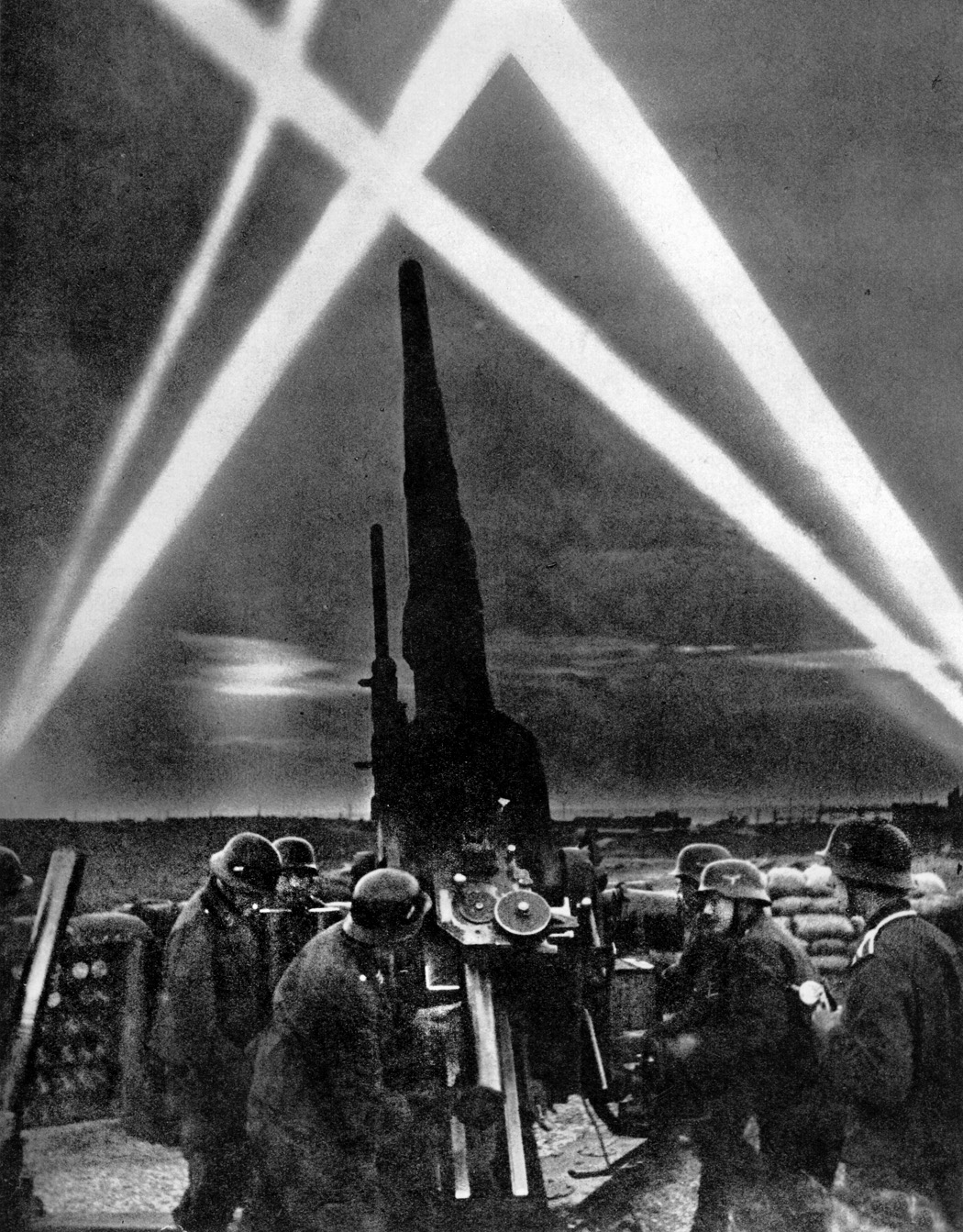

The Germans used a large number of searchlights. Although the searchlights were not particularly successful in illuminating high-flying bombers, they were also used to produce dazzle or glare to blind and confuse hostile aircrews. The main searchlights used were 60cm- and 150cm-diameter parabolic glass reflectors. Dazzle and glare made locating targets difficult and lessened the accuracy of bombing, and keeping beams direct on an Allied plane helped defending fighters approach the plane unobserved.

A searchlight battalion included three or four heavy searchlight batteries. The batteries contained up to a dozen 150cm searchlights and a number of sound locators. Except for mass employment, initial directional data for heavy searchlights were usually obtained through the use of sound locators, while light searchlights relied on picking up targets by means of search patterns. Searchlights would be laid out in belts or in concentrations along likely lines of approach to important targets. A belt usually consisted of between 10 and 30 searchlights placed 1,000 to 2,000 yards apart.

Searchlight tactics varied depending on cloud conditions. On cloudy nights, if a hostile aircraft broke through low-hanging clouds, a limited number of searchlights, in belt or other configuration, went into action. They attempted to follow the course of the aircraft along the base of the clouds in order to indicate its course to night fighters or to produce an illuminated cloud effect against which the aircraft might be silhouetted for the benefit of fighters or antiaircraft artillery.

On nights with considerable ground fog or industrial haze, searchlight beams were unable to penetrate the haze, and searchlights went into action at a low angle of elevation to diffuse a pool of light to make target location or landmark identification extremely difficult for Allied bombing crews. On clear nights, when in belts to aid fighter interception, the usual tactic was to illuminate the target by directing beams vertically too produce a wall of light against which enemy bombers would be visible to fighters attacking from the rear, or to compel the bombers, as they ran the gauntlet of lights, to fly so close that they became visible from the ground, thus enabling other lights to engage them.

Barrage balloons were used in several industrial areas and towns. The barrage balloons formed an irregular pattern of perpendicular steel cables in the vicinity of the target area and were intended to discourage hostile aircraft from entering the region and to force planes to fly at an altitude less favorable for precision bombing. Barrage balloons were usually

organized in irregular belts about five-eighths of a mile wide and 1.5 miles from the outer edge of the target area, with 200 to 800 yards between balloons. The balloons were flown at varying heights at different times, the exact height and number of balloons depending on the time of day and the weather. The average heights at which they were flown was about 6,000 to 8,000 feet, although there were reports of balloons as high as 11,000 to 12,000 feet. A smaller balloon designed to counter attacks below 4,500 feet was introduced late in the war. Balloons were coordinated with antiaircraft guns, any gaps in the balloons being covered by light and medium flak.

Aircraft warning was the responsibility of the Luftwaffe. Although part of the Air Signal Service, the Aircraft-Warning Service was a separate organization created for the purpose of observation of German air space. The Aircraft-Warning Service network was a web-like system of air-guard stations and air-guard headquarters. The stations were arranged at distances between 20 and 45 miles.

The function of the air guard stations was to report the number, type, height, flying direction, and identity of any planes flying over the sector. These reports were channeled to a center where they were filtered and evaluated for dispersal to civil and military authorities. Both long- and short-range radio-location instruments were used for warning purposes. The long-range instruments were located at intervals along the European coast for early warning, with both long- and short-range sets scattered in a net throughout rear areas to supplement visual observation.

The ever-increasing German war effort required large numbers of antiaircraft personnel to be transferred to ground combat units. This transfer was made possible without appreciably weakening antiaircraft defenses through the use of railway antiaircraft artillery, which could be transferred rapidly from place to place for the temporary reinforcement of threatened areas, and by the introduction of Heimatflak, or home defense units, involving the replacement of antiaircraft artillery personnel with factory and office workers and 16- and 17-year-old boys.

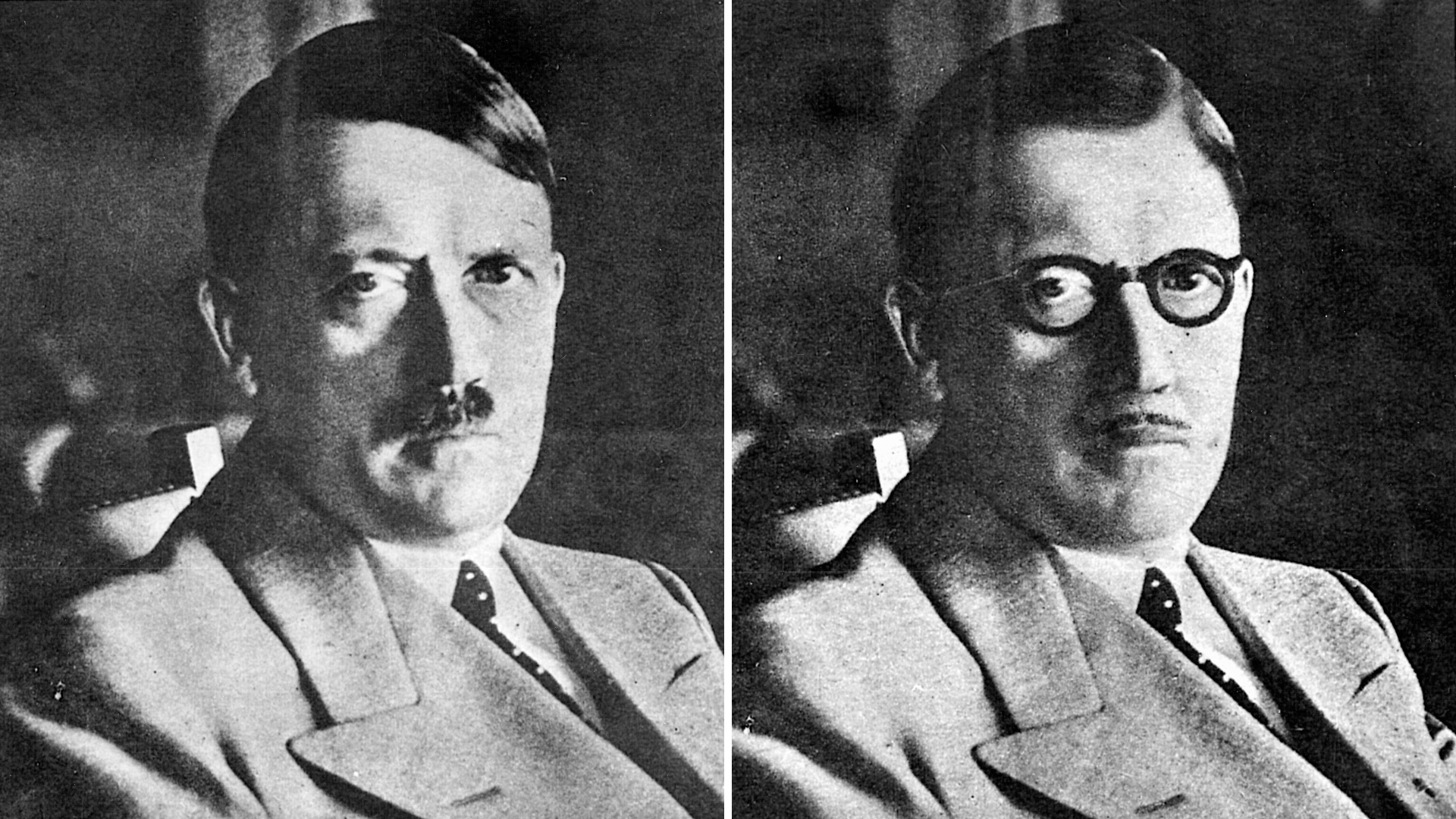

German antiaircraft defenses were highly organized and coordinated, including fighter aviation, antiaircraft artillery, warning services, and civil-defense organizations. Nevertheless, the overall result of Allied strategic bombing was essentially effective. It caused the Germans to devote nearly one-fourth of their war production to antiaircraft protection and forced them to employ massive assets to defend a wide area, while the attackers could select targets, attack weak points, and overwhelm the system when and where they chose.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments