By Arnold Blumberg

In 1941, the Philippine Islands, 7,000 in number, an American-controlled mandate, formed a natural barrier between Japan and the rich resources of East and Southeast Asia. Capture of the islands was crucial to Japan’s efforts to control the Southwest Pacific, seize the oilrich Dutch East Indies, and protect its Southeast Asia flank.

Japanese strategy called for roughly simultaneous attacks on Malaya, Thailand, American-held Guam and Wake Islands, Singapore, the Philippines, and Hawaii. Although the air strike on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, was designed to destroy the American Pacific Fleet stationed there, the other ambitious operations that commenced that day were meant to serve as preludes to full-scale invasion and permanent occupation.

The well-coordinated Japanese campaign, spread across great reaches of the Pacific Ocean, progressed with astonishing speed. The small U.S. garrisons on Guam and Wake surrendered on December 10 and 22, respectively. Four days after Wake Island was conquered, the British in Hong Kong capitulated to the Japanese attackers. Singapore, the supposedly impregnable British bastion on the Malay Peninsula, fell on February 15, 1942, to the Japanese 25th Army. Following lightning amphibious landings by the Imperial 15th Army in Thailand and Burma, Japanese troops pushed to the northwest, threatening India. The Dutch East Indies soon fell to the Japanese 16th Army.

Only in the Philippines, where the first elements of the Japanese 14th Army came ashore on December 10, did the combined U.S.-Filipino units mount a prolonged resistance, holding out for five months with grim determination and scoring some small but notable victories over their opponents.

War Plan Orange-3: The Defense of the Philippines

The defense of the Philippines against Japanese aggression had become problematic by 1941. By January of that year, Japan controlled much of the surrounding territory. Formosa, just to the north, had been under Japanese control since 1895. The islands to the east formed part of the land mandated to Tokyo after World War I. To the west Japanese troops occupied eastern China, and in 1941 they occupied French Indochina. Only the Dutch East Indies to the south remained in Western hands.

Although the United States had maintained military forces in the islands since 1898, the Philippines were unprepared for hostilities with Japan. There are several reasons for this situation. First, the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 traded a limitation upon Japanese warship construction for the abandonment of any new fortification of U.S. possessions in the Pacific. For the Philippines, this meant that only the islands near the entrance to Manila Bay were well protected. Second, with independence due to be granted to the islands in 1946, the defense of the Philippines fell almost solely on the Philippine government, whose resources were limited.

In April 1941, the United States military had recently updated War Plan Orange-3, a basis for response to Japanese aggression, which limited the defense of the Philippines to Manila Bay and important adjacent areas. War Plan Orange mandated that if attacked by Japan the U.S. Army garrison would withdraw to the Bataan Peninsula. Plan Orange did not envision a subsequent relief effort for the American forces holed up in Bataan. The administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt had decided that in the event of a new world war it would follow a “defeat Germany first” global strategy, and as a result the Philippines would have to be sacrificed.

The Philippine government passed a defense measure in 1935 intended to create a regular army numbering 10,000 men with a reserve force of 400,000 troops. After his stint as U.S. Army Chief of Staff, General Douglas MacArthur came to Manila in 1937 to train and organize the Philippine defense establishment, christened the United States Forces, Far East (USAFFE). His attempt to do so was severely hampered by a miniscule defense budget and a chronic lack of weapons, especially artillery, transport, and communications equipment. Language differences between the various elements of Philippine society prevented the effective creation of cohesive military units of any size. Further, the lack of any military schools in the islands stymied the attempt to form a cadre of commissioned and noncommissioned officers able to lead the nascent Philippine Army.

Supporting the 120,000 Philippine Army personnel were 10,000 regular troops of the U.S. Army stationed in the islands. These consisted of several American infantry regiments, two tank battalions, and the Philippine Scouts. The latter were made up of 12,000 Filipino military professional enlisted men led by American officers.

The United States rushed the best aircraft it had to the islands. They included 107 Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk fighters and 35 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers. These were designated the Far Eastern Air Force under Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton. A woefully inadequate antiaircraft defense system left American airpower in the Philippines vulnerable to enemy air attack.

In early December 1941, MacArthur organized his forces into four separate commands. The Northern Luzon Force, under Maj. Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright, defended the likely amphibious invasion areas with four Philippine Army infantry divisions and some independent infantry battalions and artillery units. It was also responsible for the Bataan Peninsula. The South Luzon Force under Brig. Gen. George M. Parker, Jr., was assigned the zone east and south of Manila with two Philippine Infantry divisions and several artillery batteries. The Visayan-Mindanao Force under Brig. Gen. William F. Sharpe was composed of two Philippine Army infantry divisions. Acting as a general reserve was the regular U.S. Army’s 10,200-man Philippine Division. The Far East Air Force was positioned just north of Manila under the direct command of MacArthur. Four artillery regiments, understrength with antiquated pieces, guarded Manila Bay. With this force, McArthur hoped to defend the main Philippine islands by defeating any enemy attack at the landing beaches.

The Japanese Invasion Begins

Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma commanded the Japanese 14th Army. In addition to his 30,000 combat veterans of the 16th and 48th Infantry Divisions, he had 60,000 ground and 13,000 air service support troops, along with two tank battalions, two regiments and one battalion of artillery, three engineer regiments, and five antiaircraft battalions. More than 500 planes from the 5th Air Force based on Formosa supported the Japanese ground forces, along with the Japanese Navy’s 3rd Fleet and 11th Naval Air Fleet.

The Japanese invasion plan foresaw their air force eliminating its American counterpart on the first day of the operation. Elements of the Japanese Army would then land in the Lingayen Gulf north of Manila and to the south of the Philippine capital at Lamon Bay. Both forces would then converge on Manila, where the decisive battle for the islands would be fought. Homma was given 50 days to conquer Luzon; after that time half his command would be withdrawn to other combat areas in Southeast Asia.

From December 8-10, devastating air attacks on the Philippine islands of Luzon and Mindanao gave the Japanese air superiority over their opponents, allowing them to make diversionary amphibious landings in northern Luzon on December 10. The U.S. Asiatic Fleet withdrew from Philippine waters soon after the air strikes. With American air and naval power in the islands neutralized in the first hours of the war, the USAFFE scheme to defend the entire Philippines went off the rails. Now the area’s sole defenders would be the ground forces, cut off from resupply, reinforcements, or escape.

On December 10, the Japanese made diversionary landings along the coast of northern Luzon. The next move came in the south when elements of the Japanese 16th Infantry Division landed in southern Luzon followed by an assault on Mindanao on the 19th. The main attack commenced on December 22 as infantry of the 16th and 48th Divisions waded ashore at Luzon’s Lingayen Gulf supported by 100 tanks. Wainwright’s poorly trained and equipped 11th and 71st Philippine Infantry Divisions could neither repel nor pin the enemy on the beaches. On the 24th, elements of the Japanese 16th Division landed at Lamon Bay against General Parker’s dispersed corps and drove north to link up with their comrades from Lingayen Gulf heading south.

MacArthur’s Rush to Bataan

Realizing that the USAFFE defense plan had failed, on December 26 MacArthur notified his subordinate commanders that Plan Orange 3, the prewar plan to defend only the Bataan Peninsula and the island of Corregidor for six months until relief came, was being reactivated. To execute Plan Orange, Wainwright’s North Luzon Force was charged with holding back the main enemy assault and keeping the road to Bataan open for use by Parker’s South Luzon Force. To achieve this, Wainwright deployed his combat units in a series of defensive lines.

Under Wainwright’s and Parker’s guidance the American and Philippine withdrawal to Bataan proceeded quickly and in relatively good order considering the chaotic situation. A particularly precarious phase of the operation occurred when the commands connected near the town of San Fernando. Both forces had to move along a single narrow road to reach the Bataan Peninsula. Although the Japanese failed to take advantage of their complete air superiority by interdicting this chokepoint in the enemy’s route of retreat, Wainwright, alarmed at the slow progress of South Luzon Force’s withdrawal, ordered a stand to be made at San Fernando. The tenacity of elements of the Philippine 21st Infantry Division allowed the Americans and Filipinos to hold this defensive position until December 30.

MacArthur’s rush to Bataan forced his retreating units to leave most of their supplies and equipment behind. At that point, the serious consequences of the shifts in USAFFE defense plans became clear. To ensure MacArthur’s original design to defend the entire Philippine island chain, supplies from the main depots at Bataan and Corregidor had been dispersed to the North and South Luzon command areas. Now with truck transport in short supply, congested roads, and limited time, the resupply of the magazines in Bataan and Corregidor proved impossible. The resulting serious lack of food, ammunition, weapons, and medical supplies would prove to be critical factors in the upcoming fight for Bataan.

Drawing the American Defensive Line in Bataan

Under the circumstances, the Americans and their Filipino allies did a remarkable job withdrawing to the Bataan Peninsula. However, the Japanese mandate to take Manila was more responsible for the defenders reaching Bataan than was their military prowess. Following Tokyo’s order to make the Philippine capital his primary goal, General Homma on December 27 rejected the suggestion from his chief of staff that the enemy was fleeing to Bataan to make a last stand and that Japanese air assets should be switched to make a sustained effort to slow the Americans retreat to Bataan, allowing Japanese ground forces time to intercept them before they could enter the peninsula in strength.

Homma wanted to heed his subordinate’s advice but could not due to his superior’s orders to make the capture of Manila the top priority of the campaign. As a result, he directed no substantial ground and air forces then attacking Manila to attempt to slow the American withdrawal to Bataan.

On January 2, 1942, Manila fell to the 14th Army. Three days later Homma received a rebuke from Imperial Japanese Army Headquarters stating that the enemy army in Bataan could not be ignored and that Homma should have destroyed it while at the same time taking Manila. What the Japanese belatedly discovered was that the bottled-up enemy army on Bataan and Corregidor effectively blocked Japanese use of Manila Bay. As a result, the Imperial Japanese Army in the Philippines would have to continue the fight for the islands.

The American plan to defend the 30-mile deep, 15-mile wide, and heavily forested Bataan Peninsula called for the manning of an initial defensive line extending across the peninsula from Mauban in the west to Mabatang in the east. Wainwright’s newly designated I Corps held the eastern sector with the 1st, 31st, and 91st Philippine Infantry Divisions, the 26th Philippine Scouts Cavalry Regiment, and a battery of 75mm guns. General Park’s Southern Luzon Force, now called II Corps, held the western zone with the 11th, 21st, 41st, and 51st Philippine Infantry Divisions. The U.S.-Filipino reserve consisted of the Philippine Infantry Division. Each American corps fielded—on paper—30,000 men.

Mount Natib, a 4,222-foot-high promontory in the center of the American line, served as the boundary between 1st and II Corps. The U.S. commands anchored their flanks on the lower slopes of the mountain, but since they considered the rugged terrain around Mount Natib to be impassable, they did not extend their lines up the mountain slopes. As a result, a considerable gap existed in the center of the defensive line.

American Artillery Dominance

As the American-Filipino forces completed their withdrawal onto the Bataan Peninsula in the first week of January 1942, MacArthur feared that the placement of his troops would be disturbed by a rapid Japanese pursuit. He need not have been concerned; the enemy allowed the Americans time to organize their Bataan defenses while they shifted units around.

In early January 1942, Japanese Imperial Headquarters took Homma’s experienced 48th Infantry Division from him, sending it to the Dutch East Indies. In its place the 14th Army received the 65th Brigade, 6,600 men strong, made up of recalled reservists, lightly armed, poorly trained, and suitable only for garrison work. This unit provided the mass of the Japanese attacking force in Bataan between January and March 1942, suffering terrible losses in the process. Although the brigade heroically did its duty, its limited training, aging members, and poor equipment prevented 14th Army from achieving victory in Bataan much earlier than possible if a more cohesive and experienced combat unit had carried the burden of the fight during the same period.

Finally, on the night of January 9, the Japanese initiated their first determined attacks against the American positions defending the Bataan Peninsula with an initial artillery barrage against the American II Corps, followed by assaults by two infantry regiments supported by tanks and artillery. After rapidly moving forward, the soldiers of Nippon were brought to a halt primarily by enemy artillery fire.

The storm of lead that stymied the Japanese advance came from American-Filipino 75mm guns placed on the main defensive line and backed up by powerful, well-concealed 155mm howitzers to the rear. The American pieces held the high ground and thus had terrific observation, while the Japanese, on lower terrain, had great difficulty spotting enemy gun positions even from the air due to the thick jungle vegetation.

The Japanese artillery effort was hobbled by the small number of pieces brought to the battle for Bataan, poor artillery doctrine, and a lack of accurate maps of the battle zone. During January 1942, the 14th Army drove the American-Filipino defenders from the Mauban-Mabatang Line with little help from the artillery. American-Philippine artillery fire completely dominated the battlefield right up to the withdrawal to the next American-Philippine defensive line.

I Corps’ Retreat South

Eight days of intense fighting raged along the American-Filipino front, especially near the Japanese salient in the line at Abucay Hacienda three miles east of Mount Natib. During this time the Japanese probed to the west, hitting the Philippine 41st Division, and then farther west, striking the 51st Division where they routed one of that formation’s regiments and were poised to rupture the entire American position. At the very moment of their apparent breakthrough, however, they were rocked by a vicious counterattack from the best troops the defenders had, the 31st “All American” Infantry Regiment and the Philippine Scout 45th Infantry Regiment, all regulars. The combat at Abucay Hacienda was a rifleman’s fight.

The Japanese finally won the battle when they concentrated their attacks against the I Corps on the western margin of the peninsula. On that front, only a single road near the sea served as a supply route for the defenders. Using their skill at small unit infiltration over difficult ground, the Japanese were able to sever the road, beating off repeated Filipino attempts to reopen the avenue.

With his reserves committed to shoring up II Corps’ front, MacArthur had no choice but to order I Corps to retreat to the south. First Corps had to abandon much of its artillery due to lack of transportation during this retrograde movement. With its left now open to attack, II Corps soon followed suit. The general retreat of the Allied forces commenced on January 22. Starting off well, by the 24th it had fallen into total confusion caused by the poor training of the average Filipino soldier, the need to move on narrow jungle roads at night, and the constant fear of Japanese attack.

Fortunately, the Japanese failed to notice their enemy’s maneuver south and did little to hinder it. When they finally set out to pursue their prey, they were held back by U.S. light tanks and artillery carried on half-tracks. By the 26th, a new American-Philippine defensive line stretching 4,500 yards ran from Bagac, resting on the shore of the South China Sea, east to Orion on the eastern margin of the peninsula.

Homma’s Attempt to Cut Off I Corps

Frustrated by the resistance his 14th Army was encountering taking the Bataan Peninsula, General Homma ordered Maj. Gen. Naoki Kimura, commander of the Japanese 16th Infantry Division, to mount an amphibious attack on the west coast to cut the West Road, the only American-Filipino north-south supply artery on the peninsula’s west coast, 10 miles behind the enemy front line. Capturing this route would sever all American I Corps combat units from their supply sources to the south. Kimura selected the 2nd Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment under Lt. Col. Nariyoshi Tsunehiro to make the watery end run.

Defending the target area was the Bataan Service Command under the 71st Philippine Infantry Division’s Brig. Gen. Clyde A. Selleck. Selleck had only a mixed bag of U.S. Marines, airmen, Philippine Constabulary (Filipino policemen turned into infantry), and four 6-inch naval guns to defend the lower third of the peninsula—40 miles of rugged terrain. In the weeks before the Japanese stepped ashore in his area, Selleck’s men were able to string barbed wire, man observation posts, and cut crude trails toward probable landing sites.

The 900 men of Tsunehiro’s 2nd Battalion set out on their mission on the night of January 22, 1942. Throughout the night, initial attempts to land at their predetermined location, Caibobo Point, met with failure due to the machine-gun fire of American airmen of the 17th Pursuit Squadron fighting as infantry, as well as an Allied 75mm artillery battery. Forgoing a landing at Caibobo Point, the Japanese sailed on and landed 600 men at Quinauan Point, where they came ashore unopposed. A second group of 300 Japanese soldiers landed simultaneously 11 miles south of Caibobo Point at Longoskawayan Point near Mount Pucot, only 1,000 yards from the West Road.

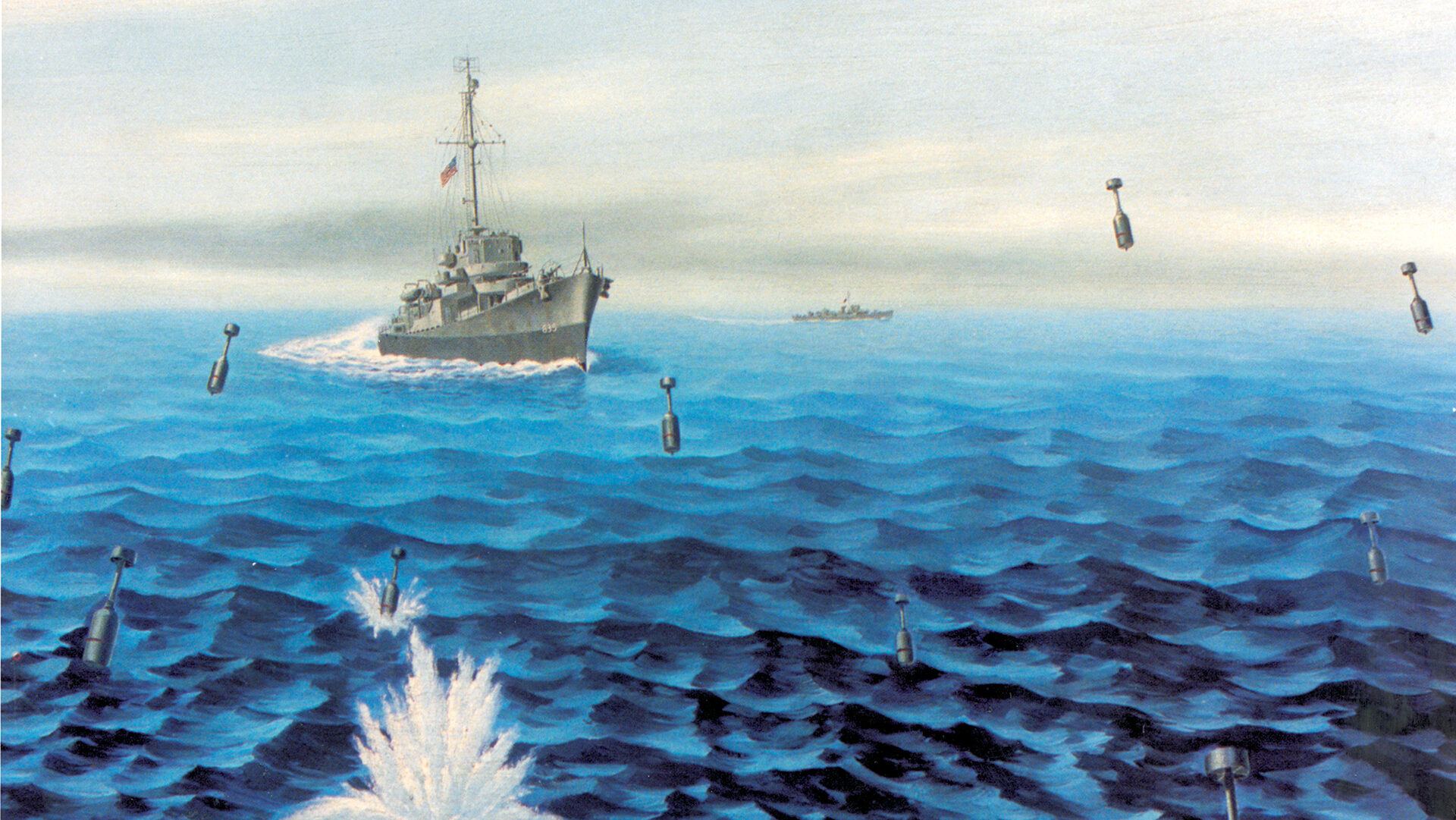

During the night, American PT-34 (patrol torpedo boat) sank two empty Japanese troop transport barges heading north from the Japanese landing sites.

During the next several days, American and Filipino beach defenders discovered the location of the two Japanese incursions. Although not trained well enough as foot soldiers to dislodge the invaders, the ad hoc American and Philippine defenders were able to contain the Japanese beachheads. The Japanese tried to reinforce the landing parties, but the attempts were made piecemeal and proved ineffectual. One company with artillery missed its intended landing zone, coming ashore at Silaiim Point, where it was quickly blockaded by the Americans.

On February 1, the balance of Kimura’s battalion (500 men) in 12 barges made the run to Quinauan Point. Not far from their destination the Japanese flotilla was spotted and attacked by four American P-40 fighters, losing five barges to the planes. Soon the Japanese were targeted by 155mm and 75mm guns and Philippine Scout machine-gun positions farther down the coast that raked the barges’ decks and killed scores of Japanese soldiers.

As the night progressed, PT-32 engaged a Japanese minelayer with torpedoes, forcing it to withdraw. Shortly after midnight what was left of Kimura’s force sailed to Silaiim Point.

It took the Americans two weeks using infantry, tanks, and artillery to dislodge the Japanese toeholds. The Imperial Army’s attempt to cut off I Corps proved a costly failure with the loss of 1,400 men. American and Filipino casualties amounted to 750, with about a third of those killed.

In late January and early February, the Japanese launched new attacks on II Corps. These efforts were costly failures. The Japanese made several amphibious landings along the west coast behind I Corps’ front, resulting in the complete destruction of the landing forces.

The Defenders Finally Surrender

In mid-February, a lull settled over the peninsula. Since January the Japanese had lost more than 7,000 battle casualties and another 12,000 men to disease. Their attack formations had been reduced to the equivalent of three infantry battalions. In addition, Homma had severe supply problems. For its part, the American-Filipino army was increasingly affected by malnutrition and disease, both factors causing the soldiers to lose so much of their physical strength that their ability to fight was seriously impaired.

Through February and March, MacArthur’s forces did what they could to prepare for a renewed enemy offensive by digging new defensive positions and reorganizing their units. On the Japanese side, reinforcements flowed onto Bataan. Among them were the 4th and 21st Infantry Divisions with 4,000 men each. Most important was the arrival of heavy artillery, including 96 150mm and 240mm cannons.

By late March, the Japanese had launched preliminary attacks to capture the enemy outpost line. On April 3, their main assault went in on a narrow front with six infantry regiments of the 4th Division and 65th Brigade supported by one tank regiment against II Corps’ left flank. A heavy artillery barrage preceded the ground forces, pulverizing the defenders’ forward and rear trench lines, wire obstacles, communications, command posts, and artillery positions. Filipino counterbattery fire was sporadic due to the intensity of the bombardment and the presence of Japanese airpower. Within 36 hours, II Corps was broken. Soon afterward, with its left flank in the air, I Corps also fled south.

Despite a counterattack by American forces on April 6, as well as stiff resistance by the U.S. 31st Regiment and Philippine Scouts, the Japanese juggernaut rolled south, pushing the routed American-Filipino forces before it. Seeing all was lost and wanting to save as many of his men from death and injury as he could, Maj. Gen. Edward P. King, Jr., commander of all U.S. and Filipino troops on Bataan, surrendered on April 9.

On May 5, after losing over half their 2,000-man assault force, the Japanese secured a landing on the fortress island of Corregidor. Reinforced by tanks and artillery, they beat off four American counterattacks, finally causing General Wainwright to surrender the post the next day. After 93 days of siege, the defense of Bataan ended. With its fall, 12,000 U.S. and 64,000 Filipino prisoners of war fell into Japanese hands. The infamous Bataan Death March and three years of cruel captivity awaited them. By June 9, 1942, all organized resistance to the Japanese in the Philippines ceased.

My late father-in-law, Herminio Abilla was a sergeant in the Philippine Scouts, a regular US Army unit which as you noted was made up of Filipino soldiers and American officers. He was stationed on the island of Mindanao during the fall. His commanding officer told the men that they were free to leave before the surrender order went into effect. While none of them were sailors, Dad and several other men took a boat and sailed to their home island of Negros, where he went up into the hills as a guerilla near his hometown of Bais. The guerillas on Negros carried out a difficult and prolonged operation to evacuate Americans left behind, eventually to board a sub. One of my wife’s schoolteachers and several relatives had roles. Dad didn’t talk much about the war, but when we visited the Chinese cemetery he told about crawling through it at night to visit his family. On the other side of the family, her grandfather was beheaded by a Japanese officer in front of his family and their home burned, a too common occurrence.

While the withdrawal to Bataan was masterfully conducted, rice to feed the army for a year was left behind in Cabinatuan, much to MacArthur’s regret. The Philippine army troops had another disadvantage. Few of them had boots, so they wore requisitioned tennis shoes. Many of their helmets had to be made from laminated plant fiber. Both Filipinos and Americans were plagued by defective grenades, mortar shells, and antiaircraft ammunition. Some of those were reloaded with dynamite and had fuses repaired or replaced. The Philippine units that had Ifugao or Negrito tribesmen did a little better on food because they had grown up in the forests and could forage. Some of them used blowguns to bring down monkeys and birds from the trees.

The original war plan was drafted when the Japanese were not thought to have had such a massive invasion force. Accordingly, the logistical support for supplies and munitions was simply inadequate. That the Americans and Filipinos held out as long as they did was a near miracle. The guerilla actions they engaged in for the next three years was even more impressive. My late wife’s family were sheltered by the guerillas on Mindanao during the occupation and food supplies were somewhat erratic but all of them survived.