By Cowan Brew

It was nearly 11 on the morning of September 20, 1863, and the woods around slow-moving Chickamauga Creek in northwest Georgia were ominously quiet. It was much different from the day before, when savage fighting had erupted all along the LaFayette Road leading northward to Chattanooga, Tennessee, 10 miles away. For nearly 13 hours the Union and Confederate armies had torn into each other with a fury that was rare, even on Civil War battlefields. The hard-pressed Federals, commanded by Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans of Ohio, had been pushed back to the road—their only lifeline to Chattanooga—and nearly overrun several times by the gray-clad Confederates in General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. They clung to the roadway like a drowning man clings to a life raft in rough seas.

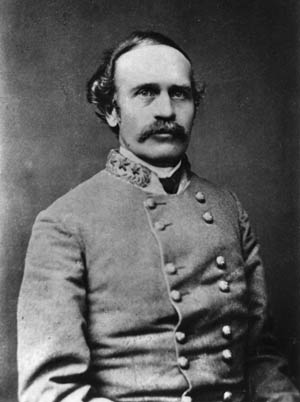

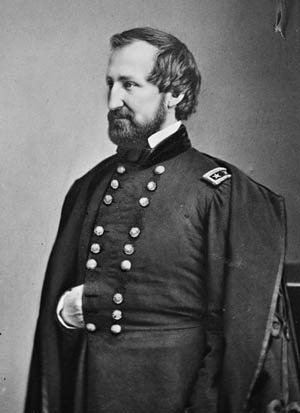

On a hillside at the extreme southern end of the battlefield, two other Ohio-born generals, one wearing Union blue, the other Confederate gray, moved into place for a life-altering confrontation. The two had met before, on another western battlefield, almost exactly one year earlier. William Haines Lytle, the Union general, was the scion of a prominent Cincinnati family. Almost startlingly handsome, with blue eyes, light brown hair, and a neatly trimmed beard, Lytle had achieved national fame as the author of a popular drawing room poem, Antony and Cleopatra. Thousands of men in both armies knew the poem by heart. A career politician, many expected Lytle to seek high office once the war was over. The White House itself did not seem beyond his reach.

His Confederate counterpart, Bushrod Rust Johnson, had no such distinguished pedigree. The son of humble, peace-loving Quakers from Belmont County in eastern Ohio, Johnson had defied family wishes by enrolling in the United States Military Academy at West Point. His motivation seems to have been financial rather than patriotic; he was working as a low-paid schoolteacher at the time. Among Johnson’s fellow cadets in the Class of 1840 were William Tecumseh Sherman and George H. Thomas. Rosecrans, now commanding the Union army in the woods opposite him, had been a couple of years ahead of Johnson at West Point.

The previous October, Lytle and Johnson had met briefly on the battlefield at Perrysville, Kentucky. Lytle had been struck behind the ear by a piece of shrapnel, knocked senseless, and was sitting atop a large rock still holding his unnoticed sword in his hand when Johnson’s adjutant, Captain W.T. Blakemore, happened by. Lytle offered Blakemore his sword, but the captain told him suavely, “One who could command such men should never suffer such indignity.” Instead, he escorted Lytle to Johnson’s tent, where the fellow Ohioan took one look at Lytle’s blood-smeared face and vacant expression and sent him back to the brigade surgeon for emergency aid. The next day, Lytle was taken to Harrodsburg and paroled. Soon Lytle and Johnson would meet again, and this time there would be no chance for mercy.

For Lytle, Johnson, and the thousands of other Union and Confederate soldiers, the long road to Chickamauga had begun two and a half months earlier, when Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland had finally broken camp near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and commenced a long-awaited advance on Chattanooga, an invaluable railhead for three crisscrossing railroads that linked the major Confederate armies to each other and to vital ports on the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico. Still a comparatively young town, only 25 years old, Chattanooga stood as the gateway to the most valuable prize in the Deep South: Atlanta. Until the Union Army captured Chattanooga, the heartland of the Confederacy would remain untouched.

President Abraham Lincoln and his brain trust knew this, but Rosecrans seemed oddly unconcerned. Both the president and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton had expended countless hours and dozens of telegrams attempting to impress that fact on Rosecrans. But the general had almost come to grief outside Murfreesboro at the Battle of Stones River at the beginning of the year. There, the implacable Bragg had launched a surprise winter attack that came within a whisker of winning the day and liberating the entire Volunteer State from Union control. Rosecrans did not intend to let that happen again. He remained stubbornly in camp for the next six months while Lincoln and others implored him to move south. “I will attend to it,” Rosecrans told them but did nothing until the end of June, when he finally began his long-delayed advance.

When Rosecrans finally broke camp, he quickly proved the rightness of Lincoln’s patience and trust in his recalcitrant general by smoothly maneuvering Bragg’s army out of Middle Tennessee and down to Chattanooga. There, protected on three sides by mountains and ridges and on the fourth by a wild and notoriously dangerous river, Bragg hunkered down to await Rosecrans’s no doubt suicidal assault. But “Old Rosy,” as well liked by his men as Bragg was despised by his own, did not intend to send them marching blithely into the mouth of Bragg’s guns. Instead, he distracted his opponent by shelling the town from the northeast while he swung the bulk of his army behind Lookout Mountain and fell upon his target from the southwest.

By the time Bragg realized what was going on, Rosecrans had three full corps across the river and clambering up the opposite heights. Bragg had no intention of being trapped inside Chattanooga like his fellow Confederate general, John C. Pemberton, had allowed himself to be trapped at Vicksburg, Mississippi, a few weeks earlier. Instead, Bragg evacuated the town completely on July 4 and retreated into the nearly impenetrable hills of northwest Georgia.

Rosecrans might have rested on his laurels, having completed the near bloodless capture of his prize target. More than one of his subordinate generals, including his second in command, Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, had urged him to do just that. But Thomas had an army-wide reputation for stodginess, and Rosecrans had been hearing endless complaints for months about his own lack of initiative. Determined to prove Washington wrong, he ordered “a general pursuit of the enemy by the whole army.”

The order would prove easier to give than to obey. To pursue Bragg, Rosecrans had to divide his army into three wings to enable it to pass through three different gaps in the mountains below Chattanooga. Meanwhile, Bragg had recovered his nerve—if indeed he had ever lost it—and prepared a gigantic ambush of Rosecrans and his entire army. He sent selected “deserters” into the Union lines to tell their captors that the Confederates were hastening southward in abject retreat. It sounded plausible to Rosecrans given what he had seen of Bragg over the past several weeks. Like a bloodhound with a strong scent, the Union commander pressed forward against his leash.

But Bragg had always possessed an underrated sense of strategy—it was in the tactical handling of his army that he had fallen short at the previous year’s battles at Perryville, Kentucky, and Stones River. Consolidating his own forces east of the mountain passes, Bragg laid plans to destroy the overextended Federals one wing at a time. Unfortunately for the Confederates, Bragg’s generals lacked their commander’s strong sense of strategy and any innate confidence in his leadership. At the site of Bragg’s first planned ambush, McLemore’s Cove, bungling, timid generalship allowed the Federals to escape the carefully laid trap and, even worse, alerted Rosecrans of the enemy’s true intentions. Immediately he ordered his own widely dispersed wings to converge upon each other in the vicinity of Crawfish Springs, 12 miles south of Chattanooga. With any luck, they might come together again before the Confederate tornado descended on them and smashed them to bits.

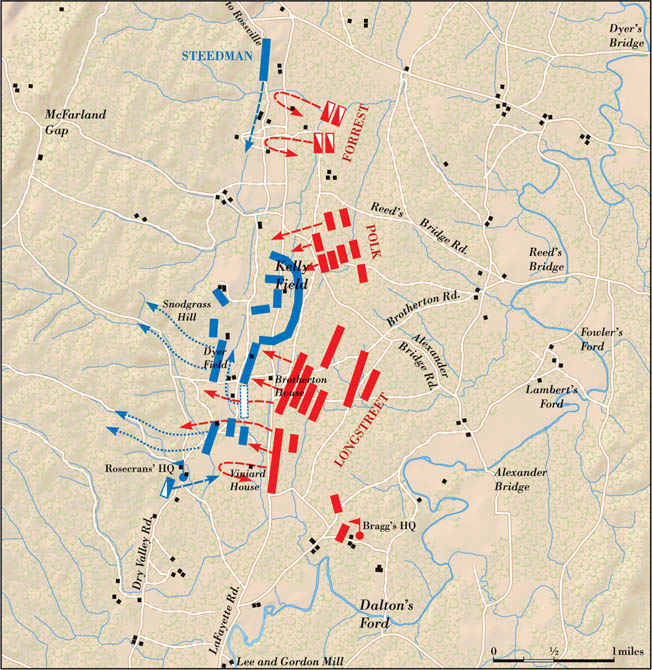

With the help of some spirited skirmishing by the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry, the three wings made it safely through the gaps and drew within supporting distance of one another on the night of September 17. Bragg, disappointed but not demoralized, sent his scouts along the eastern bank of Chickamauga Creek to find a place where he might cross and attack the Federals en masse. Two wooden bridges spanned the deep, slow-moving creek a mile and a half apart, on either side of Jay’s Mill. Reed’s Bridge to the north of the mill and Alexander’s Bridge to the south were both ideal crossing points. Once across the swirling, black-water creek, Bragg intended to fall on the enemy’s left flank somewhere in the vicinity of Lee and Gordon’s Mill.

Fortunately for Rosecrans, who always seemed to have more luck than Bragg, two sharp-eyed Union colonels, Robert Minty and John T. Wilder, were already watching the bridges for enemy movement. When the first Confederate skirmishers came thrashing through the underbrush toward the creek, the Federals peppered them with gunfire and canister. Wilder’s men, armed with new seven-shot Spencer repeating rifles, were particularly effective. Bushrod Johnson, directing the attempted crossing at Reed’s Bridge, was convinced that “the whole Yankee army was in our front, on our right and rear, while our army was still on the east side of the Chickamauga.” The delay cost the Confederates several valuable hours.

Johnson was relieved, in more than one sense of the word, when Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood rode up to him with a signed order from Bragg giving Hood overall command of the Confederate right. Hood had just arrived with the first batch of reinforcements from General Robert E. Lee’s vaunted Army of Northern Virginia. In all, some 12,000 of Lee’s battle-hardened infantrymen in Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s I Corps were en route to Georgia by train from Virginia. Longstreet, a Georgian himself, was not yet on the scene, so Hood assumed command in the interim. Hood, new to the ground, halted the Confederate advance for the night.

The Federals, still badly strung out, did not have the luxury of resting. Rosecrans issued a flurry of orders, all with the same intent—keep moving northward to Chattanooga. The prize he had thrown away so cavalierly a few days earlier now seemed like the veritable promised land itself to Old Rosy and his footsore, bone-tired soldiers. Having failed to listen to Thomas’s well-reasoned advice before, Rosecrans now placed full confidence in his generalship, ordering Thomas to anchor his XIV Corps on the LaFayette Road leading to Chattanooga. Under no circumstances, said Rosecrans, was Thomas to allow the Rebels to get around his left flank. The survival of the entire army depended on Thomas holding the road open.

Thomas’s corps reached its designated location, the Kelly House, and set up camp. Not long afterward, Colonel Dan McCook, the younger brother of the army’s XX Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook, informed Thomas that a lone Confederate brigade had gotten across Reed’s Bridge. Immediately, Thomas sent Colonel John Croxton’s brigade in search of the intruders. Croxton, a Yale-educated Kentuckian, soon sent back word that he would be happy to bring back the enemy brigade if Thomas would only be good enough to tell him which of the four or five enemy brigades now attacking him Thomas wanted Croxton to bring back.

Croxton’s chief worry was an all too familiar adversary: Confederate cavalry legend Nathan Bedford Forrest. Having spearheaded Johnson’s crossing at Reed’s Bridge the day before, Forrest had dismounted his men and placed them in the woods around Jay’s Mill. Pacing about like a panther, his face lit by a characteristic fiery glow, Forrest ignored the bullets clipping the leaves around him. “Hold on, boys, the infantry is coming,” he reassured his men. “They’ll soon be here to relieve you.”

As the fighting around the mill intensified, Thomas sent new brigades into the woods to support Croxton. Without realizing it, Thomas had unintentionally seized the battlefield initiative from Bragg and the Confederates. Expecting no Union resistance, Bragg had been calmly making plans to “attack the enemy wherever I can find him.” Now it seemed the enemy had found him first.

At this point, Bragg still had the numbers on his side. He could have easily cut through the Union line and isolated Thomas’s corps from the rest of the Federal forces—something Rosecrans had repeatedly warned Thomas not to risk. Instead, Bragg froze. As was always the case with the gloomy faced career soldier from North Carolina, once a battle got under way, he readily abandoned his careful (and usually well-reasoned) plans and allowed events, real or imagined, to control his actions. Despite much evidence that the Union left, under Thomas, was still somewhere northwest of Jay’s Mill, Bragg continued to believe that the enemy flank was farther south, at Lee and Gordon’s Mill. As the day wore on, he sent his troops forward in piecemeal fashion, thus limiting their impact. Instead of one devastating hammer blow that might have split the enemy line fatally in two, Bragg began a series of short and largely ineffective jabs.

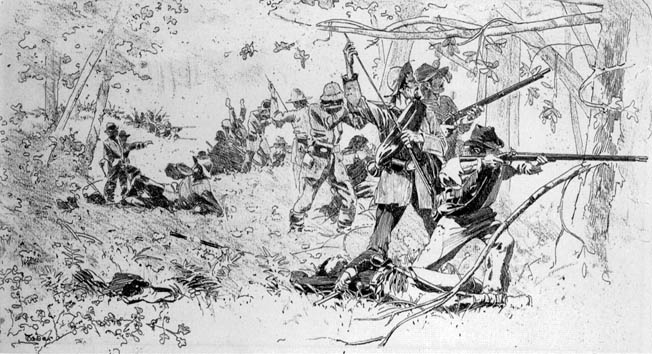

For the next nine hours, the fighting intensified along the north-south axis of the battlefield. The heavily wooded, ravine-broken terrain was so rough that neither side could see the other. Towering trees blocked the sunlight, and clinging thorns and vines tore at the soldiers’ coats. Company by company, regiment by regiment, brigade by brigade, the two armies groped toward each other in the underbrush while an angry, constant buzzing of bullets and shrapnel whirred over their heads and, all too often, into their bodies.

The battle moved irresistibly southward as Rosecrans kept feeding divisions into the fray. From Thomas’s right around Reed’s Bridge Road, the blue ranks extended past Alexander’s Bridge Road into a cornfield just east of the Kelly House and the LaFayette Road. All afternoon the fighting continued, while the opposing commanders reacted in characteristic ways. Rosecrans was buoyant and almost giddy, convinced that he was “driving the Rebels in the center handsomely” and hopeful that by nightfall “we will drive them across the Chickamauga.” Bragg entertained no such confidence. He interpreted every new development, said one of his aides, “as through a glass darkly.” When Maj. Gen. A.P. Stewart rushed to headquarters and asked for more explicit orders before attacking with his corps, Bragg told him simply that he “must be governed by circumstances.” It was not exactly ringing leadership.

Still, almost despite their commander, the Confederates came close to breaking the Union line on two occasions at twilight. Stewart’s attack on the Union center near the Brotherton cabin found a soft spot in the enemy defenses, and only the timely arrival of Brig. Gen. William Hazen’s brigade and the massed fire of 20 cannons from a narrow ridge behind Hazen stopped the Confederate advance. Meanwhile, on the far right, Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s hard-fighting division almost turned Thomas’s left before running out of ammunition and daylight. Both attacks gave the promise of victory the next day.

By the time firing died down on the 19th, some 15,000 casualties already littered the battlefield. The night turned cold, and several flash fires caused by forbidden campfires and scorched kindling broke out in the parched woods, fatally burning dozens of wounded men who were unable to crawl away. Shivering in their light jackets, the shaken survivors of the day’s fighting were kept awake by the bone-chilling cold and the blood-curdling cries of wounded soldiers. One Indiana sergeant, Thomas McGee, remembered the sounds as a wavelike sobbing, a “storm of groans and cries for help that come on the black night air. To this day, that dying, wailing petition is still ringing in our ears.” Another Hoosier, Private Alva Griest, called it simply “a terrible sound.” Stretcher bearers on both sides were foiled by understandably nervous pickets, who shot at anything they heard moving in the dark.

At his headquarters near the Union right, a log cabin belonging to local widow Eliza Glenn, Rosecrans held a late-night strategy session. He was uncomfortably aware that although he had fought Bragg to a standstill that day the initiative still lay with the Confederates, as the two twilight assaults had indicated. “We were greatly outnumbered, and the battle the next day must be for the safety of the army and the possession of Chattanooga,” he recalled after the fact. Whenever he asked for advice from his assembled officers, a drowsy Thomas would respond, “I would strengthen the right.” He couldn’t tell Rosecrans where, exactly, such reinforcement could be found. All Rosecrans could do was order him to “defend your position with the utmost stubbornness. In case our army should be overwhelmed it will retire on Rossville and Chattanooga. Send your trains back to the latter place.” It was not an order designed to inspire confidence.

Bragg, typically, held no strategy session. After the Confederate defeats at Perryville and Stones River, he was under no illusions about the confidence—or lack thereof—that his subordinate generals placed in him. Instead, Bragg climbed into an ambulance and fell asleep. He was still sleeping when James Longstreet arrived on the battlefield at 11 pm, having endured a bone-rattling train ride from Virginia and a near-fatal encounter with Union pickets in the dark. Longstreet was more than a little irked that Bragg had neglected to send anyone to meet him at the train station in Ringgold, forcing him and his staff to ride unguided to the battlefield. It was a less than welcoming reception for the celebrated commander of Robert E. Lee’s I Corps in the much more successful Army of Northern Virginia.

Longstreet hid his annoyance long enough for Bragg to outline his plans for the next day’s fighting. For inexplicable reasons, Bragg had decided to divide his already jumbled and confused forces into two new wings. Longstreet would command the Confederate left, while Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk would command the right. Polk was to initiate the fighting at dawn, with each brigade to attack successively, north to south, as soon as the brigade to its right had set off.

It was a confusing plan, depending on a newly arrived general (Longstreet) leading forces he had never met, while Polk, an Episcopal bishop before the war with little military training or aptitude, took over the crucial role of attack initiator. The change left various Confederate generals to wander about the field all night trying to locate their new troops and sending couriers back and forth in the darkness in a vain attempt to determine their roles in the next day’s attack. Bragg simply went back to bed, assuming that everyone understood the perplexing new plan as well as he did.

Predictably, things went wrong from the start. The next morning, Bragg waited confidently for the resumption of firing. Nothing happened. Polk, having received no written orders from Bragg, was casually lounging on the front porch of a farmhouse three miles behind the lines, waiting for his breakfast. Meanwhile, his subordinate commanders, Lt. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill and Maj. Gens. John C. Breckinridge and Patrick Cleburne, sat around a campfire wondering what Polk was waiting for. It never occurred to Bragg to ride a mile to the front and see what was—or wasn’t—happening.

The heaven-sent delay allowed Rosecrans’s pioneer companies to continue strengthening the Union lines. They had worked all through the night felling trees and building breastworks, and canny veteran infantrymen had helped, scooping out foxholes with their canteens and constructing firing blinds with clear lines of sight trained on the dark woods lowering to the east. When the Confederate brigades stepped out of the tree line, they would be waiting for them.

Nearly four hours behind schedule, the Confederate attack resumed at 9:45 am. A “perfect tornado of bullets” greeted them, Kentucky Lieutenant W.W. Herr remembered. Herr’s commander, Brig. Gen. Benjamin Hardin Helm, Abraham Lincoln’s brother-in-law, fell in the first wave leading an attack on the Union breastworks. Dozens of futile attacks followed, doing nothing except to alarm Thomas, who frantically sent couriers galloping south to implore Rosecrans to send him reinforcements. And Rosecrans, himself uneasy and overly excited, delivered an impromptu tongue lashing to one of his division commanders, Brig. Gen. Thomas Wood, who was not moving quickly enough in his eyes. The brief outburst would soon prove to have disastrous consequences for the entire army.

Receiving yet another panicky demand from Thomas for reinforcements, Rosecrans decided to transfer Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s division from the far right of the Union line to Thomas’s left. At the same time, he ordered the just chastised Wood to move his men back into line to fill an erroneously reported gap left by Sheridan’s movement. Wood was quick to obey the order, even though he knew there was no gap in the line. Either through blind obedience or simple spite, he immediately stopped his division from following Sheridan and headed back to close the nonexistent gap. “Gentlemen, I hold the fatal order of the day in my hand and would not part with it for five thousand dollars,” Wood reportedly told aides.

At almost the exact moment that Wood was pulling out of line, Longstreet simultaneously unleashed his 11,000-man attack column, which he had massed just east of the Brotherton cabin. Bushrod Johnson, who had known Longstreet at West Point and in the peacetime army, was selected to lead the assault. It would be the highlight of his life.

“Our line now emerged from the forest into open ground on the border of long open fields, over which the enemy were retreated,” Johnson reported. “The scene now presented was unspeakably grand. The resolute and impetuous charge, the rush of our heavy columns sweeping out from the shadow and gloom of the forest into the open fields flooded with sunlight, the glitter of arms, the onward dash of artillery and mounted men, the retreat of the foe, the shouts of the hosts of our army, the dust, the smoke, the noise of fire-arms—of whistling balls and grapeshot and bursting shell—made up a battle scene of unsurpassed grandeur.”

For Union General William Lytle, his fellow Ohioan and brief acquaintance, the scene was more awful than grand. Seated on his horse on a nearby rise, ever afterwards to be known as Lytle Hill, the spruce little general watched in horror as the Union right dissolved with almost miraculous suddenness. Hordes of gray-coated demons, screaming themselves hoarse above the unremitting sound of musket and cannon fire, were now headed straight for him. Pulling on a pair of dark kid gloves, Lytle said, perhaps to himself, “If I must die, I will die as a gentleman.” Then, turning to his men in the 1st Brigade, he shouted, “All right men. We can die but once. This is the time and place. Let us charge. If we can whip them today we will eat our Christmas dinner at home.”

Lytle’s counterattack, doomed from the start, fell apart as quickly as it began. The two sides came together at the base of the hill, fighting with bayonets, muskets swung like clubs, and even rocks picked up from the ground. Lytle, astride his charger, was an easy target. One bullet crashed into his spine; almost simultaneously, three more stuck him in the body and face, knocking out several teeth and exiting through his neck. He died, choking out his last words, “Brave, brave, brave boys.”

Unaware of his old adversary’s fate, Bushrod Johnson rode exultantly behind his own men, spurring them on. John Bell Hood, veteran of many of Robert E. Lee’s battles in Virginia, gave him simple but dynamic advice: “Go ahead and keep ahead of everything.” A moment later, Hood fell to the ground, his right leg shattered by a bullet near the hip. His arm was still in a sling from a serious wound suffered 10 weeks earlier at Gettysburg.

With Longstreet’s breakthrough at the Brotherton cabin, the battle was effectively over, and both sides knew it. Rosecrans, stunned by the disaster, watched the Confederates pouring toward him on the hill where the Widow Glenn’s cabin was located. Turning to Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana, a recent unwelcome visitor from the War Department who had come to observe—some said spy—on him, Rosecrans gave some terse, if well-chosen advice. “If you care to live any longer,” said the general, “get away from here.”

Rosecrans was not long in following his own advice, spurring his horse northward down the Dry Valley Road in the rear of the battlefield. At his side rode his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. James A. Garfield, yet another Ohioan. The two rode in silence for several miles, stopping from time to time to put their ears down Indian-style to the ground to listen for the direction of the heaviest firing. At a fork in the road between the battlefield and Rossville Gap, they came literally to the turning point of their lives.

Rosecrans wanted to go back and organize a last-ditch defense with Thomas. Garfield, a political general with no pre-war experience, convinced him to go instead to Rossville and prepare for the defense of Chattanooga while Garfield rode over to Thomas to find out what was happening. It was a spur of the moment decision that altered both their lives. Rosecrans would lose his command and his career for giving the appearance of abandoning his army at the height of its crisis. Garfield, cantering across the field alone, rode up to Thomas a few minutes later to give him the unnecessary news that the Union right had given way. Seventeen years later, canny campaign managers would turn “Garfield’s Ride” into a stirring moment of high drama and heroism, propelling the rider straight into the White House where an assassin’s bullet soon propelled him back out again.

Thomas, reinforced by the remnants of the Union right, fell back to a strong defensive position on Snodgrass Hill, the highpoint of Horseshoe Ridge. There, he held off repeated Confederate assaults, winning for himself the somewhat ironic title, “The Rock of Chickamauga,” which failed to take into account the fact that his incessant demands for more and more reinforcements had led Rosecrans to inadvertently create a gap in his own lines to provide those reinforcements.

At dusk, Thomas withdrew from the field, leaving behind a wrecked tableau and more than 34,000 casualties—the highest two-day total of the entire war—including the body of William Lytle, which was returned under flag of truce that night to Union lines. Standing atop Snodgrass Hill, the exultant Confederates poured cheer after cheer into the night air. It was, said Indiana soldier and future writer Ambrose Bierce, “the ugliest sound that any mortal ever heard—even a mortal exhausted and unnerved by two days of hard fighting, without sleep, without rest, without food and without hope.”

Trudging back into Chattanooga, which they had abandoned all too readily 11 days earlier, the defeated Federals attempted to process the catastrophe. “We have met with a serious disaster, extent not yet ascertained,” Rosecrans wired Washington. Dana had already beaten him to the punch. “My report today is of deplorable importance,” he informed his superiors. “Chickamauga is as fatal a name in our history as Bull Run. Our soldiers turned and fled. It was wholesale panic.”

Dana’s report, motivated at least partly by vindictiveness over Rosecrans’s brusque treatment of him personally, was considerably exaggerated, but not unexpected. “Well, Rosecrans has been whipped as I feared,” said Abraham Lincoln. “I have feared it for several days. I believe I feel trouble in the air before it comes.” Secretary of War Edwin Stanton chimed in: “I know the reasons well enough. Rosecrans ran away from his fighting men and did not stop for thirteen miles. [Alexander] McCook and [Thomas] Crittenden made pretty good time away from the fight to Chattanooga, but Rosecrans beat them both.”

The fact that Rosecrans still held Chattanooga did not seem to register on anyone, not even the general himself. Only Nathan Bedford Forrest, an untutored genius of warfare, realized the true significance. Standing atop Missionary Ridge overlooking the town, Forrest sent message after message to Bragg, who was still loitering around the battlefield at Chickamauga, begging him to renew the attack while the Federals were still disorganized. Bragg, typically, refused. “What does he fight battles for?” Forrest wondered aloud. It was a question that would be asked and answered in the weeks to come.

The Union learned a bitter lesson, Lincoln lost his brother in law, but the Union remains and eventually overcome of the obstacles and prevailed