By Mike Phifer

An unrelenting rain soaked the gray-clad troops of Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s reinforced division of Confederate soldiers on the morning of March 30, 1865. Following along with the foot soldiers was Colonel William Pegram and six guns from his artillery battalion, which were being pulled by mud-caked horses. The weary Confederates did their best to ignore the miserable weather as they tramped west on White Oak Road away from the main body of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia defending Petersburg, Virginia.

Pickett’s force was bound for the vital road intersection known as Five Forks a few miles away. The mud and sheets of rain were not the only obstacle impeding Pickett’s progress. Federal cavalry shadowed the Confederate column. “Instead of pushing on, [Pickett] stopped, formed a regiment in line-of-battle, and awaited some attack,” wrote Captain W. Gordon McCabe, Pegram’s adjutant. “Much valuable time was lost in this way.”

Pickett’s men reached Five Forks in the late afternoon. Waiting for them was Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee and his two brigades of Virginia cavalry, who had done their best to keep back the enemy cavalry throughout the day. General Robert E. Lee, who commanded the Confederate army, had ordered Pickett and Fitz Lee to launch a pre-emptive strike against a large force of Federal cavalry massing six miles to the southeast at Dinwiddie Court House on the Boydton Plank Road.

It was critical to the survival of Lee’s army that Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan’s cavalry force at the court house should be driven off, for they threatened the South Side Railroad, the last Confederate-controlled rail line entering Petersburg. If the Federals succeeded in cutting the railroad, it would precipitate the fall of both Richmond and Petersburg.

With nightfall fast approaching, Pickett decided to remain at Five Forks for the night. He ordered his men to construct breastworks, which they did to the best of their abilities, before bivouacking with the rain still falling. The fate of Lee’s army rested on Pickett’s shoulders.

By late March 1865, the situation facing Lee was decidedly grim. For the past 10 months his army had been enduring a withering siege at Petersburg in their desperate attempt to defend the capital of the Confederacy at Richmond. Field works stretched for more than 30 miles from Richmond south to Petersburg and continued for another six miles southwest to Hatcher’s Run.

Lt. Gen. General Ulysses S. Grant, the general-in-chief of Union army, had succeeded in wearing down his nemesis. In February 1865 Lee’s army numbered 55,000 troops, but by late March the number of men under arms had decreased owing to desertion and battle attrition. Facing Lee’s army were 128,000 Federal troops in two armies. Maj. Gen. George Meade’s commanded the larger Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. Edward Ord led the smaller Army of the James. In addition, Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah had arrived in the tidewater region from the Shenandoah Valley to augment Grant’s forces.

In late March Grant drew up plans for Maj. Gen. Gouverneur Warren’s V Corps and Maj. Gen. Andrew Humphrey’s II Corps to march around the Confederate right flank at Hatcher’s Run. Once around the Confederate right flank, the forces were to turn north. Grant intended by these moves to draw the Confederates out of their trenches by forcing the Rebels to defend the South Side Railroad. Lee would have to take some of his forces out of line to counter the movements, and that would weaken his fortified line sufficiently for other Union forces to pierce it.

Sheridan had a key role to play in the movement to cut the South Side Railroad. His cavalry corps was to swing to the left of the two Union infantry corps and occupy Dinwiddie Court House, which was situated 15 miles southwest of Petersburg. Once there, Sheridan was to use the court house as a base for further operations. His next objective was to secure the strategic intersection of Five Forks. Ford’s Road, one of the main roads that passed through Five Forks, led directly to the South Side Railroad.

If the Confederates abandoned their trenches and came out into the open, Sheridan had orders to pin them down while the rest of Grant’s forces moved to reinforce the attack at Five Forks; however, if the Confederate remained in their Petersburg trenches, then Sheridan’s troopers were to tear up track along the South Side Railroad, as well as the Richmond and Danville Railroad. The two railroads joined in Burkeville, VA, with the Richmond and Danville leading into the Deep South.

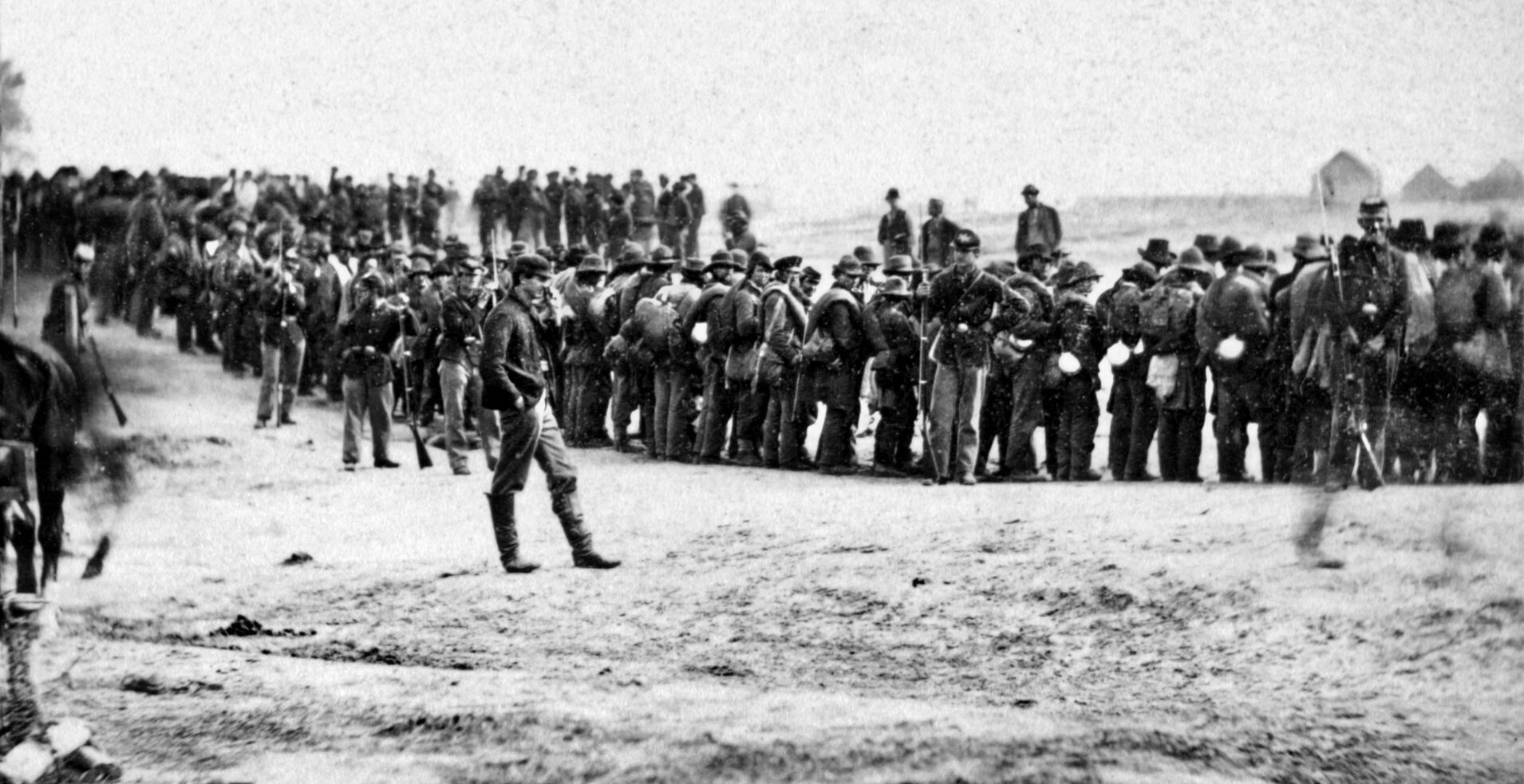

In the early hours of March 29, Maj. Gen. Romeyn Ayres’ Second Division of the V Corps began its march to outflank the Confederates. Maj. Gen. Charles Griffin’s First Division and Maj. Gen. Samuel Crawford’s Third Division followed Ayres. Ayres’ troops reached Rowanty Creek in the late afternoon. The Union II Corps followed the V Corps.

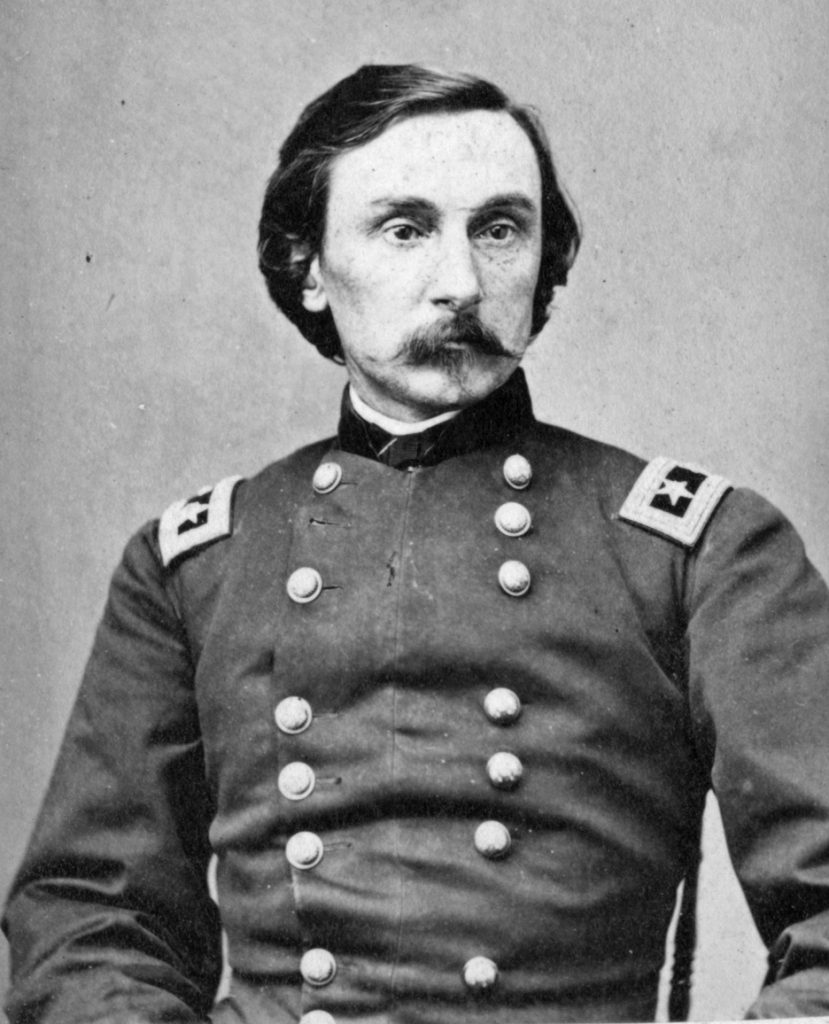

After constructing a pontoon bridge across the creek, they continued their march. Warren ordered Griffin to turn north onto the Quaker Road, which it did at noon. The vanguard of Griffin’s division consisted of Brig. Gen. Joshua Chamberlain’s 1st Brigade.

As for Sheridan’s Cavalry Corps, it embarked from its camp before sunrise on March 29. Maj. Gen. George Crook’s Second Division, on loan from the Army of the Potomac, struck out along the Jerusalem Plank Road. Brig. Gen. Thomas Devin’s First Division and Brig. Gen. George Custer’s Third Division followed Crook. Custer’s troops, at the rear of the column, accompanied the army’s wagon train. Sheridan, who remained the commander of the Army of the Shenandoah, had placed his cavalry corps under the direction of Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt. The cavalry forces reached Dinwiddie Court House that night.

Confederate scouts reported to Lee that the Federal cavalry was on the move. Lt. Gen. James Longstreet suggested the creation of a task force to address the threat that they posed to the South Side Railroad. Longstreet suggested to Lee that the task force consist of Pickett’s Division of Longstreet’s Corps based at Richmond, a substantial cavalry force, and several artillery batteries.

Lee concurred with the proposal and ordered Pickett to prepare for the mission. Lee ordered his nephew, Fitz Lee, to bring his cavalry division to Petersburg, where it arrived on March 29. This gave Fitz Lee a total of seven cavalry brigades.

By that time, Lee had learned that Federal infantry had crossed Rowanty Creek and that Sheridan’s initial destination was Dinwiddie Court House. Lee correctly surmised that the Federal cavalry would attempt to ride through Five Forks on its way to the South Side Railroad.

When Fitz Lee arrived at Petersburg, Lee ordered him to ride to Sutherland Station, where he was to join forces with Pickett and two more cavalry divisions, one of which was led by Lee’s son, Maj. Gen. William “Rooney” Lee, and the other by Maj. Gen. Thomas Rosser. Lee gave command of the cavalry corps to Fitz Lee. Since Fitz Lee was now the cavalry corps commander, Colonel Thomas Munford assumed command of Fitz Lee’s cavalry division.

Pickett’s three brigades converged on Petersburg. They were commanded by Brig. Montgomery Corse, Brig. Gen. George Steuart, and Colonel Robert Mayo, who commanded Brig. Gen. William Terry’s Brigade. Pickett’s division entrained at Richmond on March 29 bound for Sutherland Station.

Grant soon revised his orders to Sheridan on the eve of Little Phil’s advance, instructing him to “push around the enemy if you can, and get on his right rear,” wrote Grant. The next morning, March 30, with the rain still coming down hard, Sheridan set out to follow Grant’s orders. Sheridan ordered Merritt to take Devin’s First Division and reconnoiter north towards Five Forks.

Not long after Devin’s horsemen set out towards Five Forks, Grant sent Sheridan another message telling him to call off the operation due to the heavy rains and poor condition of the roads. Believing this was a serious mistake, Sheridan rode to Grant’s headquarters, where he convinced the general-in-chief to continue with the operation.

Lee arrived at Sutherland Station on March 30 to confer with the senior officers in that sector. He met with Lt. Gen. Richard H. Anderson, Pickett, and a few other generals regarding how to counter Sheridan’s threat. Lee soon learned that Fitz Lee was on his way to Five Forks with a large cavalry force. Lee decided to reinforce Pickett with the brigades of Brig. Gen. William H. Wallace and Brig. Gen. Matthew W. Ransom of Maj. Gen. Bushrod Johnson’s Division of Anderson’s IV Corps, as well as six guns from Colonel William Pegram’s artillery battalion.

Lee directed Pickett to take his reinforced division of 6,400 infantrymen and Fitz Lee’s 4,200 troopers and secure Five Forks. In so doing, Pickett would be able to block Sheridan’s advance towards the South Side Railroad, as well as the Confederate rear. Pickett set out west on White Oak Road in the late morning for Five Forks. His infantry bivouacked in the pouring rain at Five Forks that night. By the next morning, all three Confederate cavalry divisions were assembled at Five Forks.

On the morning of March 31, Pickett prepared for a move against Sheridan. The vanguard of Pickett’s force consisted of the cavalry troopers from Rooney Lee’s and Rosser’s divisions with Pickett’s infantry division forming the main force. Pickett’s foot soldiers swung west to strike Sheridan left flank.

By mid-morning, the rain had stopped falling. Just then Brig. Gen. Rufus Barringer’s troopers of Rooney Lee’s Division ran headlong into the 2nd New York Mounted Rifles of Brig. Gen. Charles Smith’s Cavalry Brigade. In the ensuing skirmish, the Rebels drove the Union cavalrymen back across Fitzgerald Ford, which was the southernmost crossing of Chamberlain’s Creek, the closest ford to Dinwiddie Court House.

Once on the east side of the crossing, the New Yorkers, with the support of the 6th Ohio Cavalry, poured a hot fire into the Rebel cavalrymen on the opposite side of the stream. When the Confederate horsemen fell back, Smith sent a detachment from the 1st Maine Cavalry across the stream in pursuit.

After wading through the rain-swollen ford, the Mainers encountered Barringer’s main force of Tarheel cavalry and were driven back across the ford. Enduring a hot fire, dismounted troopers of the 5th North Carolina Cavalry splashed through the ford in pursuit of the Yankees. It was a risky proposition, and they soon found themselves in dire need of assistance.

A squadron of the 13th Virginia Cavalry of Brig. Gen. Richard Beale’s Brigade crossed the ford. The 2nd North Carolina Cavalry followed the Virginians. A short distance to the north, the 1st North Carolina Cavalry also crossed the stream. Troopers of the 1st Maine and 6th Ohio Cavalry fired their carbines into the squadron of Virginia troopers and drove them back across the ford, where they took refuge with Barringer’s horsemen.

At mid-afternoon Barringer attacked again. The 2nd North Carolina Cavalry encountered strong resistance from dismounted Federal cavalrymen who had by that time entrenched. The 1st North Carolina Cavalry crossed north of the ford and ran into a wall of fire. At that point, Rooney Lee decided to commit all four of the regiments of Brig. Gen. Richard Beale’s brigade to the battle in a bid to overpower the Yankees. The weight of two Confederate cavalry brigades, those of Baringer and Beale, was enough to put the Federals to flight.

Meanwhile, at Danse’s Ford, which was the northernmost crossing of Chamberlain’s Creek, Pickett’s infantrymen and Rosser’s cavalrymen attempted to ford the stream. A detachment of troopers from Maj. Gen. Henry Davies’ First Brigade of Crook’s Second Division was guarding the ford. Most of Davies’ troopers had ridden south to assist Smith’s troopers, but finding that their help was not needed, they were returning to Danse’s Ford when they heard fighting erupt at the ford. Davies urged his troopers forward to assist the detachment that had remained behind.

At that time, Corse’s brigade, at the head of Pickett’s long column of infantry, was approaching the ford. The Virginians waded through the ford and brushed aside the detachment of cavalry guarding it. Just as they did so, Davies reached the crossing. He sent Colonel Matthew Avery’s 10th New York Cavalry to slow the Rebel infantry’s advance. Avery ordered his troopers to dismount. Corse’s soldiers unleashed a few well-directed volleys that forced the New Yorkers to hastily remount. Davies ordered his troopers to fall back.

Just to the east, Devin’s two cavalry brigades were approaching Five Forks by mid-afternoon when they heard a battle raging to their southwest. With a regiment of Michigan cavalry, Devin rode in the direction of the gunfire. He ran headlong into Davies’s troopers, who were in full retreat. Unable to rally them, Devin sent a message for Colonel Charles Fitzhugh to bring his 2nd Brigade forward to assist in checking the Rebel infantry’s advance.

Just at that time, Munford joined the battle, pressing south on the Dinwiddie Court House Road. As he did so, Corse continued his advance. Realizing that he had collided with a large body of enemy infantry, Devin ordered both Fitzhugh’s 2nd Brigade and Colonel Peter Stagg’s 1st Brigade to fall back before they were overwhelmed. Both Union cavalry brigades took up positions on John Boisseau’s farm, where they formed a new line.

With Confederate forces having successfully wedged themselves between Devin’s vanguard at the Boisseau Farm and the rest of the Union cavalry at Dinwiddie Court House, Merritt ordered a general retreat. The brigades of Davies, Stagg, and Fitzhugh all reached the protection of Dinwiddie Court House by nightfall on March 31.

With the Union situation deteriorating rapidly, Sheridan ordered Brig. Gen. John Gregg’s 2nd Brigade of Crook’s Division and Gibbs’ 3rd Brigade of Devin’s Division to counterattack the Confederates advancing on Dinwiddie Court House. The two Union brigades slowed the Confederate juggernaut but could not stop it. Sheridan then sent an urgent dispatch to Custer instructing him to leave one brigade with the wagon train and hurry forward his two other brigades. Leaving Brig. Gen. William Wells’ 2nd Brigade to guard the wagons, Custer rushed to Dinwiddie Court House with Colonel Alexander Pennington’s 1st Brigade and Colonel Henry Capehart’s 3rd Brigade.

Custer’s troopers deployed a half mile north of Dinwiddie Court House. Custer ordered his brigadiers to have their troops dismount and entrench. Lieutenant James Lord’s 2nd U.S. Light Artillery, Battery A, unlimbered behind Custer’s cavalrymen. Gregg’s 2nd Brigade and Smith’s 3rd Brigade, both of Crook’s Division, deployed on opposite ends of Custer’s line.

Despite the growing darkness, Pickett hurled his Confederate foot soldiers at the entrenched Union cavalry. The Union cavalrymen blazed away with their breech-loading carbines while the artillery roared in support. Stunned by the firepower, Pickett’s line reeled under the heavy fire. Fitz Lee’s gray-clad troopers assailed the Union left but were soundly repulsed by Smith’s cavalrymen. At that point, Pickett decided it was too dark to continue his attack. Pickett’s pre-emptive strike against Sheridan constituted the Battle of Dinwiddie Court House.

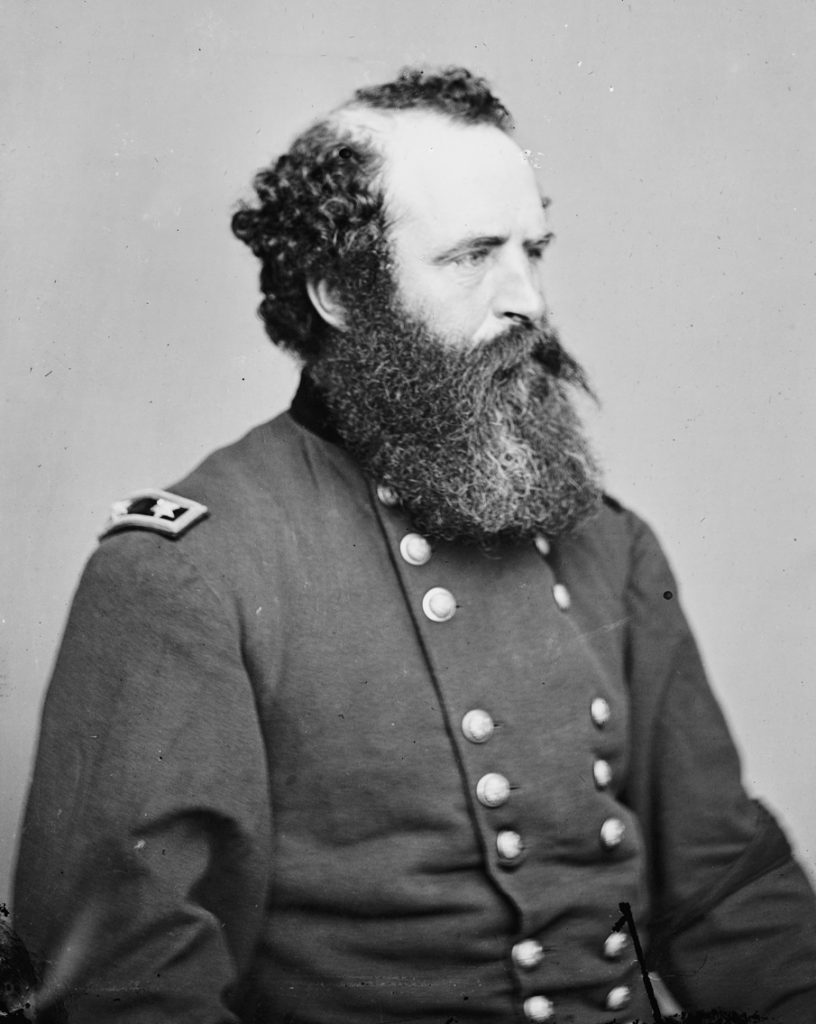

A separate battle that would be known as the Battle of White Oak Road had raged to the east the very same day between Confederate and Union infantry. Warren, whose troops were positioned just south of the White Oak Road, ordered Aryes to make a reconnaissance in force towards the road to determine whether the Confederates were nearby. Aryes in turn ordered Brig. Gen. Frederic Winthrop, who held the extreme right of the division, to perform the task with his 1st Brigade.

On the morning of March 31, Lee had personally inspected the Confederate positions along White Oak Road. He learned from scouts that Ayres’ Division was advancing northwest towards the White Oak Road and ordered Johnson to attack Ayres.

For the task at hand, Johnson had his remaining brigades, those of Brig. Gen. Henry Wise and Colonel Martin Stansel (commanding Moody’s Brigade), as well as temporary command of the brigades of Brig. Gen. Eppa Hunton and Brig. Gen. Samuel McGowan. Johnson ordered Hunton to deploy his brigade in a tract of forest just north of the White Oak Road. Stansel and McGowan moved into position to support Hunton’s attack.

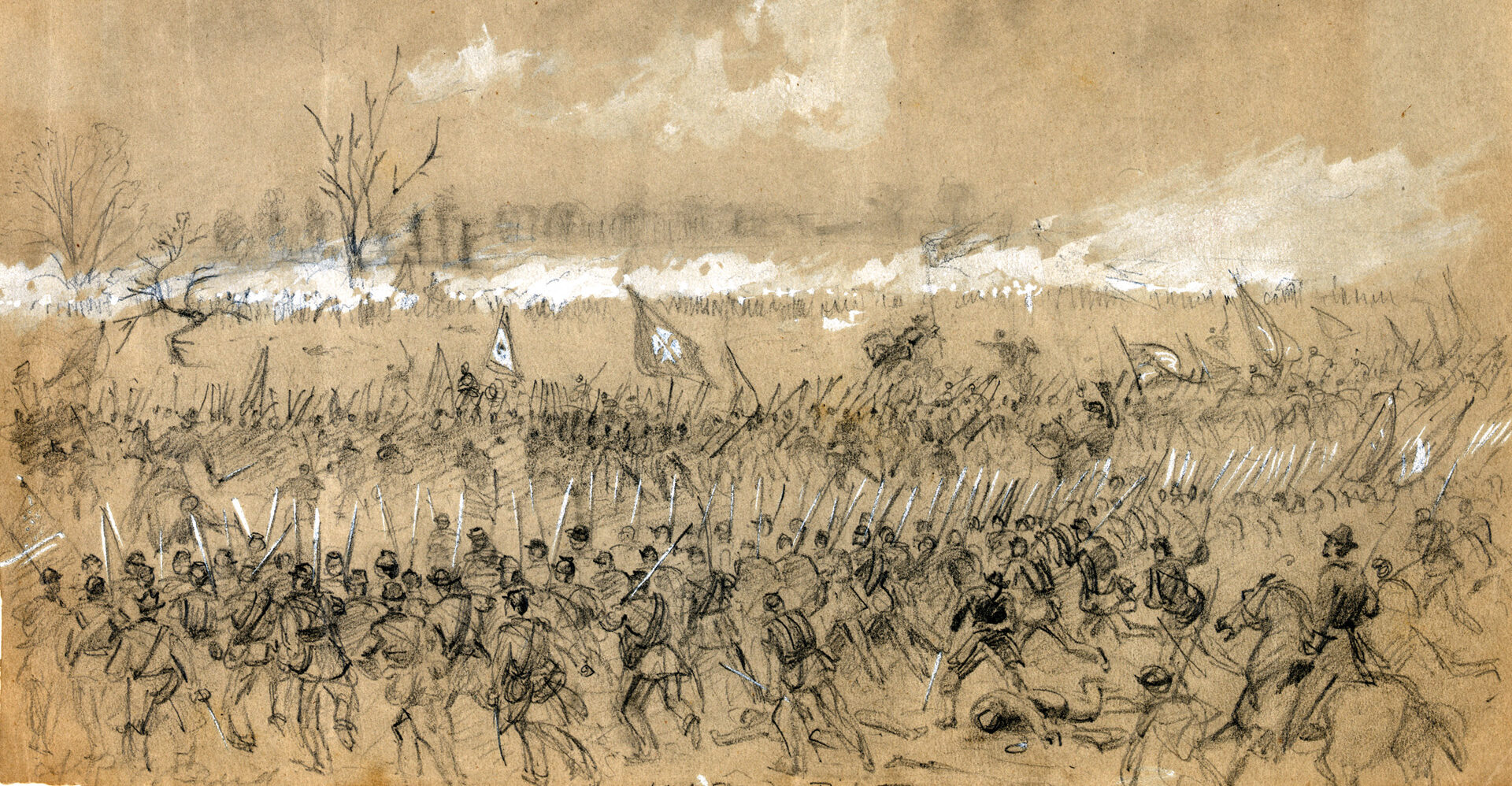

Winthrop’s brigade was struggling in the late morning through a ploughed field headed for the forest where Hunton’s men were stationed. As the Yankees came within range, the Confederates fired a tremendous volley at the Yankees. To their surprise, the Yankees continued their advance.

Hunton’s troops came crashing out of the forest. As they did so, they screamed the blood-curdling Rebel Yell. The Confederates following Hunton joined the attack. Winthrop soon found his brigade taking fire from three directions.

Although Ayres’ other two brigades came to Winthrop’s assistance, they were unable to check the Confederate advance. Demoralized Yankee foot soldiers began streaming towards the rear with the Confederates hot on their heels. After routing the greater part of Aryes’ Division, the Confederate juggernaut smashed into Crawford’s Division. Crawford’s men also joined the retrograde movement.

“Let them through or they will break our line!” Griffin shouted when he saw panicked Yankees from the other two divisions sweeping towards his own troops, which were deployed along Gravelly Run. Griffin ordered his brigades into position and braced for the enemy’s onslaught. Union batteries wheeled into position, unlimbered, and opened fire. Their rapid fire helped slow the momentum of the attacking Confederates. The Confederates, who were winded from their attack, eventually received orders to regroup at the captured enemy breastworks along the White Oak Road.

By this time, Warren had rallied his two broken divisions and had sought support from the II Corps. Humphries ordered Brig. Gen. Nelson Miles to attack on Warren’s right with his division. They struck Wise’s Brigade, who had been sent in by Lee to support the initial Confederate success, and drove them back toward their lines.

In the early afternoon, Warren and Griffin rode to the left of their line to confer with Chamberlain. Warren ordered Chamberlain to retake the ground lost to the Rebels. Moving across Gravelly Run, Chamberlain’s Yankees moved cautiously forward. Supporting him were the Gregory’s 2nd Brigade and Bartlett’s 3rd Brigade.

Chamberlain flung his troops headlong at the Rebel position. The Confederate fire was so devastating that the men of the 198th Pennsylvania began to waver. With the support of Gregory’s troops on his right flank, Chamberlain’s Yankees drove the Rebels out of their position. The Rebels withdrew north across the White Oak Road to their fortified lines.

The Confederates lost 800 men, and the Federals suffered 1,900 casualties at the Battle of White Oak Road. It might have been a tactical draw, but the Union V Corps emerged from the battle able to proceed west along White Oak Road to Five Forks.

Warren received orders from Grant at 5:00 pm to secure his position and watch his left flank. Despite being told by army headquarters that Sheridan was advancing, the rumble of battle from his direction indicated otherwise. Believing Sheridan in need of assistance, Warren dispatched Maj. Gen. Joseph Bartlett’s 3rd Brigade to render aid to the Union cavalry.

Although Sheridan was in need of infantry support given that Pickett’s reinforced division was too strong for him, he also saw an opportunity. Sheridan explained to Lt. Col. Horace Porter, Grant’s aide-de-camp that “[Pickett is] in more danger than I am; if I am cut off from the Army of the Potomac, he is cut off from Lee’s army, and not a man in it should ever be allowed to go back to Lee.”

Due to a barrage of confusing and conflicting orders throughout the evening from both Grant and Meade, it was not until 2:00 am on April 1 that Ayres’s Division was on the march to Dinwiddie Court House. By early morning, Warren also had his two other divisions in motion as well to support Sheridan.

Shortly after dawn on April 1, Sheridan greeted Chamberlain by asking if he knew Warren’s location. Chamberlain told Sheridan that Warren was probably at the rear of his division. “That’s just where I should expect him to be!” snapped Sheridan with evident disgust. Yet Warren was more than justified to be in that location because he was assisting Crawford in disengaging quietly from the Confederates. Warren was concerned that if they Confederates knew Crawford was disengaging, they might take advantage of the situation and renew their attack.

Pickett became aware that morning that Warren was marching to aid Sheridan. Pickett reasoned that if he kept his infantry in a forward position between Five Forks and Dinwiddie Court House, he might be exposing it to attack from the rear. He therefore ordered his troops to reoccupy their breastworks at Five Forks. As the Confederate infantry withdrew, Custer’s cavalry followed. Lee weighed in on the situation, warning Pickett to “hold Five Forks at all hazards.”

When they returned to Five Forks the Confederate foot soldiers set to work expanding their breastworks. When they finished, their fortified line extended for nearly two miles along White Oak Road. At its east end, the line turned north for 150 yards to protect the flank most likely to be attacked by the Federal forces. From east to west, the five infantry brigades were Ransom, Wallace, Steuart, Terry, and Corse.

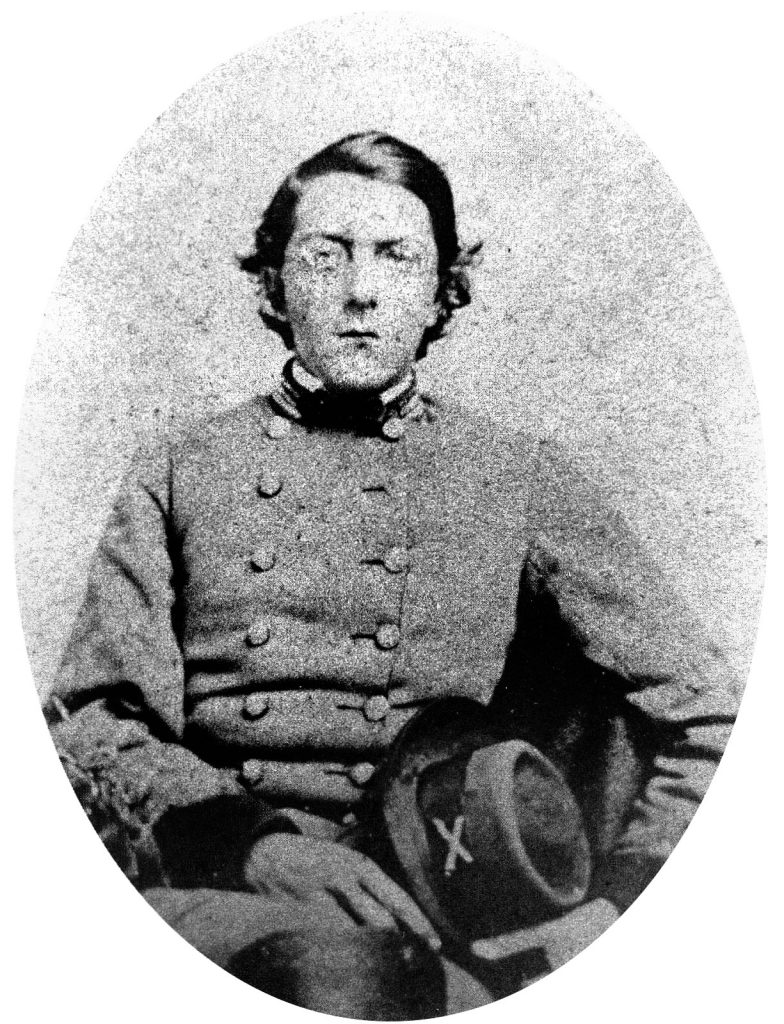

Three guns of Colonel Willie Pegram’s artillery battalion were positioned on the right of the line, while the remaining three were posted in the center of the line at the Five Forks intersection. The eight guns of Major William McGregor’s horse artillery also strengthened the Rebel line.

To Rooney, Lee posted his three brigades of cavalry on the right of the Confederate line. Munford posted his two brigades of cavalry behind the infantry on Ford’s Road in the center behind the Confederate infantry. Rosser’s two brigades of cavalry took up a position deep in the Confederate rear on the north bank of Hatcher’s Run.

To attack the Confederate position, Sheridan had 12,000 troops in the V Corps, as well as 10,000 troopers in the three cavalry divisions of Devin, Crook, and Custer. As part of his strategic plan, Custer’s troopers were to make a feint against Pickett’s right, while Devin’s troopers attacked the Confederate center. Sheridan intended the Federal cavalry to pin Pickett’s troops in place so that Warren’s V Corps could roll up Pickett’s left flank.

Although he met with Sheridan at 11:00 am, it was not until two hours later that Warren received orders to have his divisions assemble at Gravelly Run Church in preparation for the attack. With word sent to his division commanders to get their men moving, Warren rode over to Sheridan’s command post, where he was informed of the plan and how the Rebels were posted. Sheridan would later claim that he concluded the meeting with Warren by telling the V Corps commander that he wished Warren’s troops to form up on the Gravelly Church Road. Sheridan said he had specifically told Warren to form his corps for battle with two divisions to the front, aligned obliquely to the White Oak Road while one held in reserve.

As the afternoon wore on, Sheridan grew increasingly impatient with Warren. His main concern was that Warren was not moving his troops fast enough against the Confederates at Five Forks. Sheridan again met with Warren and told him that he was concerned that his cavalry forces might exhaust their ammunition keeping the Confederates occupied while Warren’s infantry moved up to make its attack. Little Phil also was concerned that the sun might set before the infantry attack began. Sheridan believed that Warren did not want the attack to begin that afternoon.

The V Corps was formed up and ready to advance at 4:15 pm. Munford, who had been watching the Federal infantry array for battle, sent a courier to inform Pickett, but neither Pickett nor Fitz Lee had expected a major Federal attack that day, and so they both accepted an invitation from Rosser to join him on the north bank of Hatcher’s Run for a shad bake. Unfortunately, neither Pickett nor Fitz Lee had informed their subordinate commanders where to find them in case of an emergency.

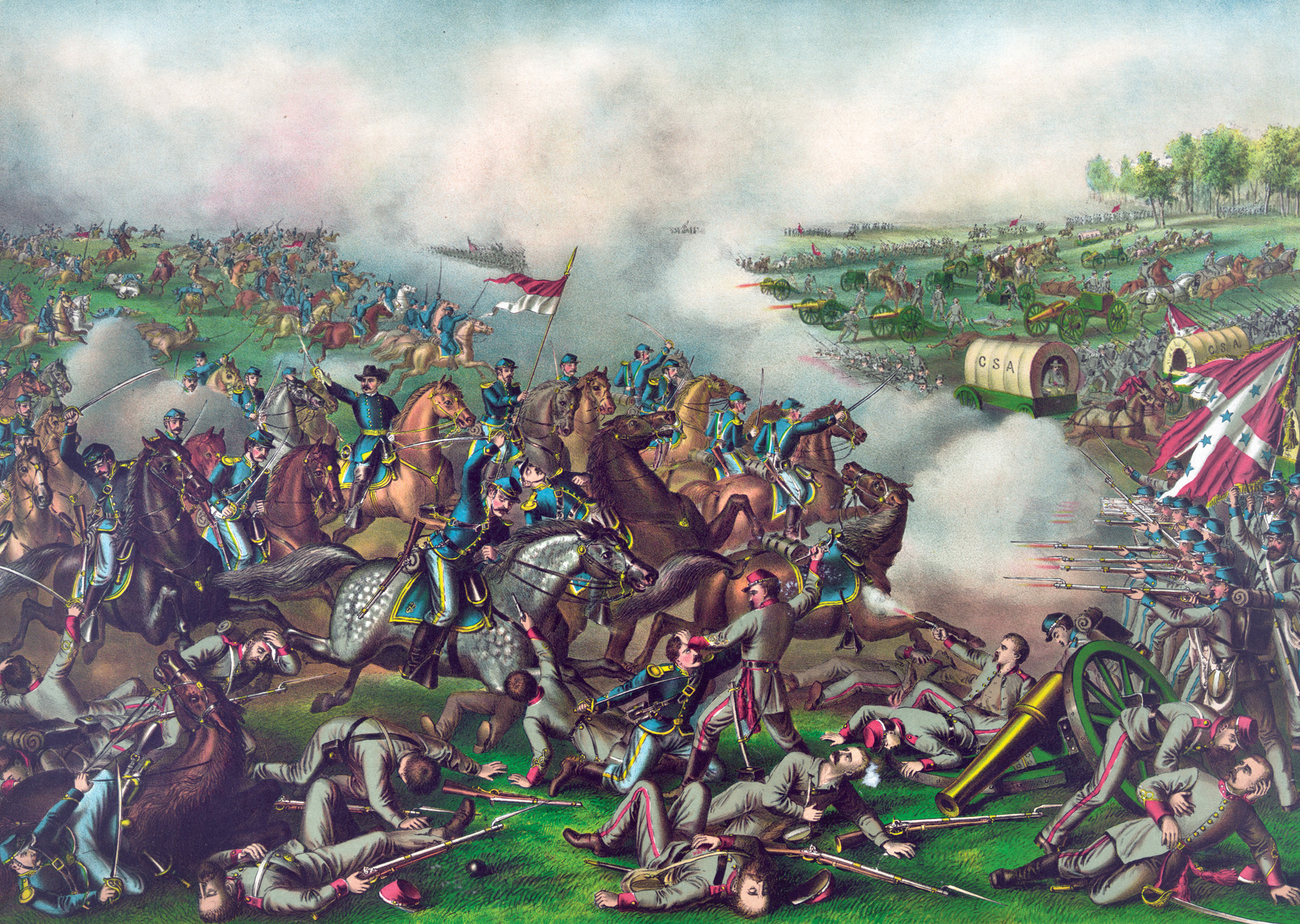

With its battle flags fluttering in the wind, Warren’s V Corps stepped off to the attack with Ayres’ Division on the left and Crawford’s Division on the right. Griffin’s Division followed Crawford’s Division. Warren and Sheridan rode with Ayres as he moved towards the Confederate left flank. Sheridan’s plan was to have Crawford strike the angle of the Rebel line that was refused to the north, while Ayres assaulted the Confederate main line facing south along the White Oak Road. Griffin would be in reserve behind Crawford.

As Ayres’ three brigades crossed over the White Oak Road, Ransom’s Tarheels raked their left flank with a heavy volley. It soon became evident to the division commanders of the V Corps that the Confederate angle they were supposed to strike was not where they had expected it, but much further to the west. Because of this, they nearly overshot the Confederate flank.

Ayres reoriented two of his brigades to face the Confederates’ refused line, which was partially veiled by thick woods. At the same time, Crawford continued his advance. The soldiers of Griffin’s Division, which was following closely behind Crawford, could hear musket fire both to their left and front. Although Bartlett’s 3rd Brigade continued to follow Crawford, Griffin’s other 1st and 2nd brigades turned to the west.

Chamberlain, whose brigade formed the vanguard of Griffin’s division, halted his brigade so that he could conduct a personal reconnaissance. He rode towards the sound of the firing on his left. From the vantage point of a low rise, he observed Ayres’s bluecoats engaged in a confused, swirling melee. Not waiting for orders, Chamberlain led his troops west toward the fighting. Brig. Gen. Edgar Gregory, commanding Griffin’s 2nd Brigade, followed Chamberlain.

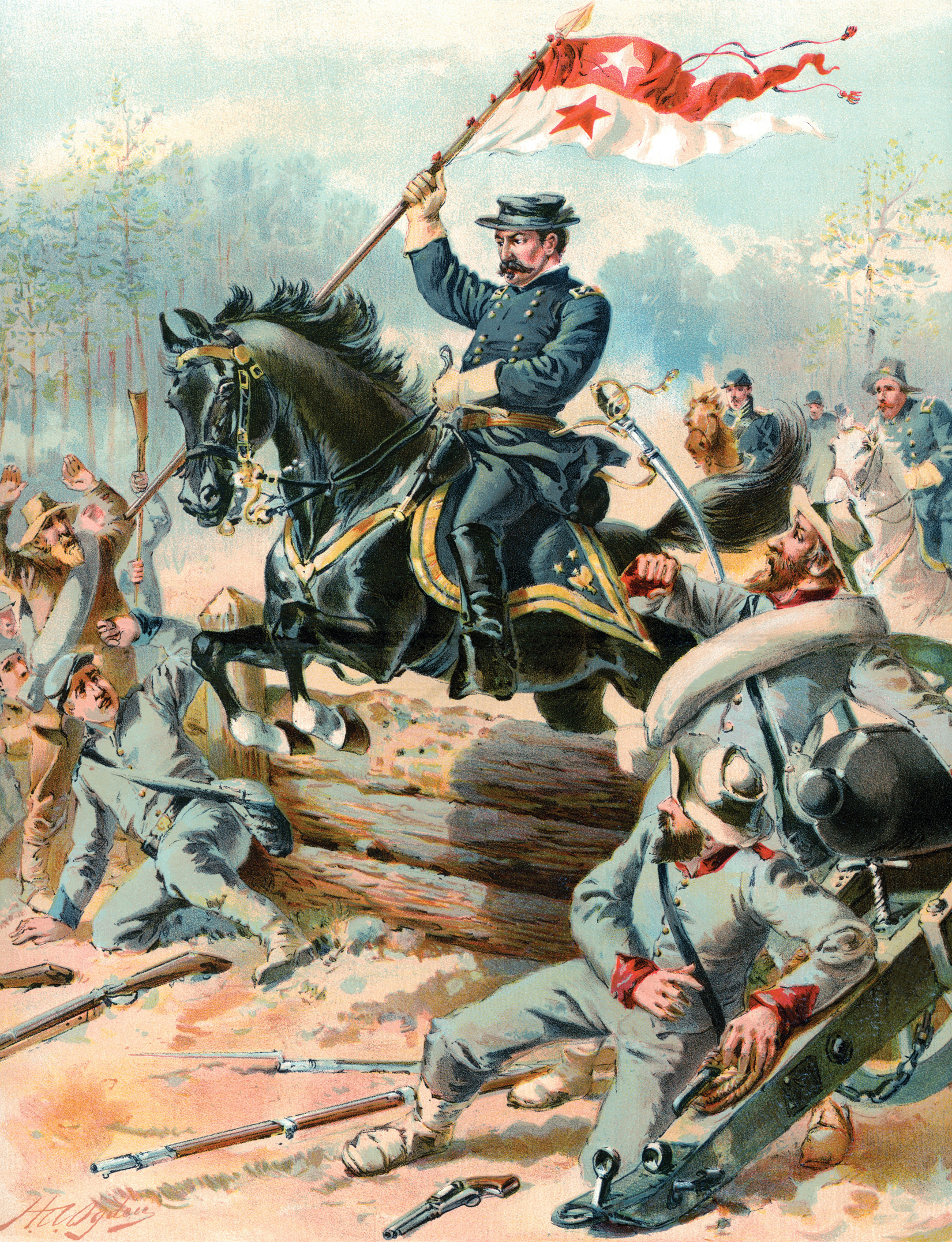

Ayres ordered his two repositioned brigades forward at the double quick. Sheridan rode back and forth along the Federal line rallying his men. “Go at ‘em with a will!” he shouted. At the first sign that the Confederate line was breaking, he yelled for his troops to pursue the enemy.

Just at that time, Brig. Gen. James Gwyn’s 3rd Brigade, which was going into action north of Ayres’ 1st and 2nd brigades, began to waver. Seeing Gwyn’s bluecoats hesitating, Sheridan galloped over to the brigade, waved his battle flag, and directed them forward.

With blue-coated infantry about to overrun their position, McGregor’s artillerymen limbered up their four guns and drove their guns out of the earthworks as quickly as their horses could pull them. Some of Ransom’s North Carolinians continued to blaze away at the rushing wave of bluecoats, while others fled or surrendered.

Ayres held his sword aloft and led his 1st and 2nd brigades over the breastworks, while Gwyn’s 3rd Brigade took them in the flank. Always in the thick of the fighting, Sheridan jumped his horse over the enemy works and began directing Confederate prisoners to the rear.

Ayres’ troops had seized the key part of Pickett’s line and had rounded up hundreds of prisoners. Although there was not much daylight left, Sheridan desperately wanted to press on towards the South Side Railroad. This was because he believed the tactical situation might change dramatically overnight given that Lee liked to make immediate counterattacks.

Warren had established a command post several hundred yards behind Ayres’s division, from which he could direct his forces and receive dispatches from his subordinate commanders. The V Corps commander observed Crawford’s division was moving north, rather than northwest towards Five Forks, and he dispatched an aide to redirect the division. When he did not hear back from the aide, Warren rode off to find Crawford himself. By that time, Crawford had advanced far enough that he was in the rear of the Confederate position. When Warren caught up with Crawford, he directed him to turn south on Ford’s Road to come in behind the Confederate line.

While Warren was conferring with Crawford, the Confederate line was unraveling. Ayres’ attack shattered Ransom’s Brigade, which uncovered the flank of Wallace’s Brigade. When Wallace’s troops fell back, they jeopardized the position of Steuart’s Brigade in the center of the Confederate line.

To protect the Five Forks intersection and Ford’s Road, Steuart tried to establish a new line facing east to check the advance of Ayres and Griffin, while Mayo attempted to form a new line facing north to check Crawford’s advance. The result was a new line at a right angle from the main line of breastworks. The Confederates desperately tried to entrench their new line, but their position had completely crumbled. By that time, Pickett’s division was facing attack from four directions at once.

The Federals surged forward, sensing victory. Griffin and Bartlett cooperated with each other and succeeded in routing the left wing of the Confederate line. The Federals were soon rounding up prisoners from the brigades of Ransom, Wallace, and Steuart.

While the Confederate disaster at Five Forks was unfolding, Pickett, Fitz Lee, and Rosser enjoyed their shad bake unaware of the battle unfolding a short distance away owing to an acoustic quirk. A thick growth of cedars between the two positions may have buffered the sound. Pickett learned of the disaster unfolding at Five Forks when his dispatch riders reported running into large numbers of Federal troops. There was little that Pickett could do at that point anyway because the Confederate line at Five Forks was already broken and most of the troops were too demoralized to rally.

Unaware of the extent of the disaster, though, Pickett mounted his horse and asked Colonel Thomas Owen’s 3rd Virginia Cavalry to open a path for him through the Yankees. With his head down behind his horse’s neck, Pickett galloped unscathed through a hail of bluecoats’ bullets to the Confederate line. Since Fitz Lee was unable to get through, he remained with Rosser’s division.

With a new threat coming from the north, Pickett ordered Mayo to pull his brigade out of the main line. Mayo rushed his foot soldiers, along with a section of artillery, to Ford’s Road to stop Crawford’s westward advance. They put up valiant resistance, but the Yankees hurled them back. Crawford’s foot soldiers sensed victory was near, and they continued their relentless advance.

As soon as firing erupted to the east, Devin’s dismounted troopers and those of Colonel Alexander Pennington’s 1st Brigade of Custer’s Division struck the main Confederate line. Small arms and artillery fire initially drove them back, but the troopers reformed and attacked anew. With the bulk of the Confederate infantry brigades being pulled out of the line, the detachments left behind to fight rearguard actions found themselves hard pressed to hold back the advance of the dismounted Federal cavalrymen.

Three of Pegram’s guns helped to cover the Five Forks intersection. “Our officers were as cool as on parade, and the men were serving their guns with a precision and rapidity beyond all praise,” recalled McCabe. Pegram was amid the storm of iron and mini balls, calmly sitting on his horse. He directed his artillery crews to fire canister at the dismounted Federal troopers. “Fire your canister low, men,” he instructed. At that moment, a Federal bullet knocked him out his saddle. “Oh Gordon! I am mortally wounded, take me off the field,” exclaimed Pegram. McCabe rushed to his side. With the help of some of the artillerymen, the devoted aide loaded Pegram into an ambulance wagon, which rattled off toward Ford’s Depot on the South Side Railroad.

It was none too soon, for Federal troopers were soon clambering over the earthworks, and the foot soldiers of both Ayres’ and Griffin’s divisions were advancing from the east. The Confederate left wing at Five Forks collapsed. Despite the disaster befalling them, the Confederate troops posted on the extreme right had some success. The mixed force of cavalry and infantry under Rooney Lee and Corse, respectively, repulsed repeated attacks by Custer.

Pickett ordered Corse to establish a new line in a field near the White Oak Road. His job was to form a rearguard that would buy enough time for the five shattered Confederate brigades to escape the clutches of the Federals. His men took up their new position and hastily threw together makeshift breastworks.

Continuing to advance with Crawford’s Division, Warren observed the Rebel attempt to establish a new line. He quickly ordered Crawford to position his troops for an attack against the new line. When Crawford’s Yankees hesitated to attack, Warren grabbed the corps flag and rode forward with his staff officers to spur the men into action. This did the trick, and Crawford’s men surged forward.

The Confederates could not stop the blue tide. Warren had his horse shot from under him just a few yards from the Rebel works. The Federals overran Corse’s position. Corse’s men joined the retreat as night fell over the battlefield. Despite Lee’s stern words to hold Five Forks at all hazards, Pickett had lost the crucial intersection to the Yankees.

To his great shock and dismay, Warren was informed at nightfall by Sheridan’s Chief of Staff Colonel James Forsyth that he was relieved of command. Earlier in the day, Sheridan had received permission from Grant to relieve Warren if he deemed it necessary. Sheridan, who considered Warren’s performance that day as lackluster at best, replaced him with Griffin. Warren sought out Sheridan and asked him to reconsider his decision.

“Reconsider, hell!” shouted Little Phil. “I don’t reconsider my decisions. Obey the order!” Sheridan directed Warren to report for follow-up orders to Grant. Warren reached Grant’s headquarters at Dabney’s Mill at 10:00 pm. His presence put a momentary damper on the celebration in progress over Sheridan’s glorious victory at Five Forks.

Following the battle, Grant put Warren in charge of the City Point sector, a depot on the James River far from the front lines. A court of inquiry in 1879 deemed Sheridan’s action unjustified. But there was a long delay before the findings were published, and Warren passed away before they became public.

As for Pickett, he would undoubtedly have been defeated, even if he had never attended the shad bake, because Sheridan outnumbered him by more than two to one. But Lee was in no mood for forgiveness given the high cost of the defeat at Five Forks. He relieved Pickett of duty and told him to report to Confederate President Jefferson Davis. “Pickett ought to have been shot,” said one of the artillery commanders serving under him. “I saw him at the close of the fight, thoroughly rattled, and telling his officers in disarrayed tones to get out the best they could.”

Munford called the Battle of Five Forks the Waterloo of the Confederacy. The battle had been a decisive victory for the Union Army. The Confederates lost 600 killed and wounded, and 4,500 captured. Lee could ill afford to incur such heavy losses at that point in the war. As for the Union V Corps, it recorded 103 killed, 670 wounded, and 57 missing. Union cavalry losses remain unclear.

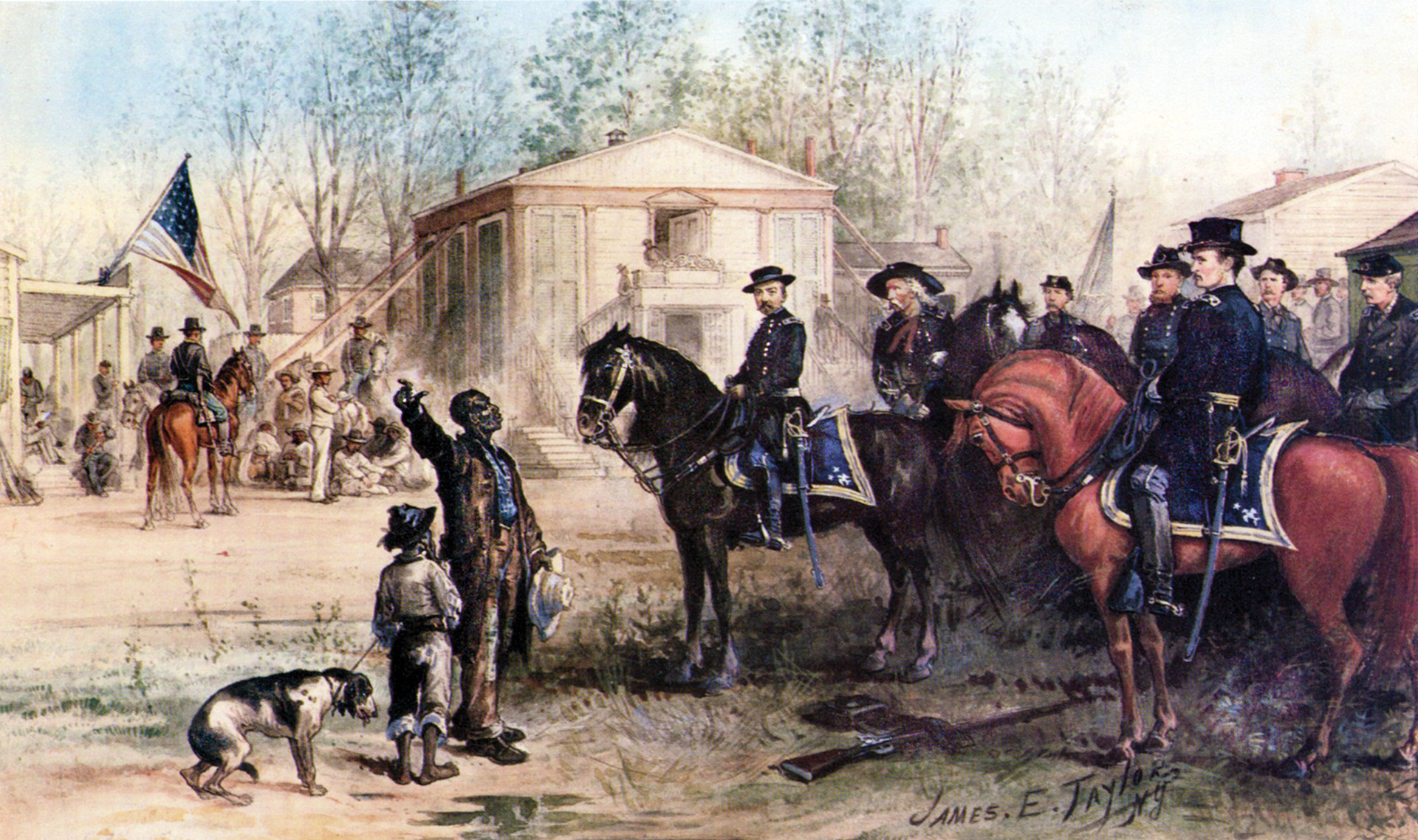

With Five Forks in Federal hands, Lee’s position quickly became untenable. Lee’s army abandoned Petersburg and Richmond on April 2 and began a week-long march west with Grant in full pursuit. The two commanders met at the McLean House in Appomattox Court house on April 9, where Lee agreed to surrender the Army of Northern Virginia. The Confederate debacle at Five Forks had hastened Lee’s surrender.