By William E. Welsh

The late summer day began like many others on the Maine coast. Seagulls wheeled overhead, seals sunned on seaweed-covered ledges, and the ocean pounded rocky headlands. The gun-brig HMS Boxer was anchored on the morning of September 5, 1813, at the mouth of Pemaquid Harbor. The Boxer’s crew had patrolled the Maine coast for two months unchallenged by American warships. During that time, it boarded and inspected American vessels it encountered with impunity.

That morning the crew of the Boxer had signaled to a company of Maine militia gathered on the grounds of old Fort Frederick that they wished to come ashore under a flag of truce. Not wishing to provoke the British commander into firing his guns in anger, Captain John Sproul signaled his approval. It turned out the British mariners simply wanted to pick blueberries.

After a time, a lookout aboard the Boxer shouted that a tall ship was approaching from the west. Thirty-year-old Samuel Blythe, commander of the Boxer, quickly recalled the shore party. The ship’s sails were set, and it moved out to sea. As it departed, the ship fired one round as a salute to acknowledge the militia’s hospitality.

The previous day, a local fisherman had watched as the Boxer escorted a merchant vessel to the mouth of the Kennebec River a short distance southwest of Pemaquid. The fisherman immediately set sail on the 25-mile voyage southwest to Portland. He wanted to inform the commander of the brig USS Enterprise that a British warship was operating nearby.

The Enterprise, commanded by 28-year-old Lieutenant William Burrows, had arrived in Portland on August 31 to patrol the waters of Maine. Shortly after dawn the following morning, Burrows attempted to reach the open sea but encountered difficulty in a tight passage owing to a strong incoming tide. To assist him, local captains towed him through the passage with their boats. Once in the open waters, Burrows set a course northeast in search of the Boxer.

The events that led up to the War of 1812 began as far back as 1792 during the French Revolutionary Wars and had continued into the Napoleonic Wars. Both French and British warships had interdicted American merchant ships in an effort to prevent their enemy from being supplied by a neutral United States during these long wars. American merchants not only carried their own cargo but routinely transported cargo for other nations as well.

Through the landmark Essex case in 1804, the British High Court of Admiralty had increased the authority of British warships to stop merchant ships of neutral nations. When the ruling was confirmed in 1805, search and seizures by British warships increased dramatically.

President Thomas Jefferson, who served two terms from 1801 to 1809, had favored a peaceful solution in which war would be avoided through economic measures and diplomacy. Neither his Non-Importation Act of 1806 nor the Embargo Act of 1807—which called for a total embargo on trade—achieved any discernible change on behalf of the British. The latter was extremely difficult to enforce and therefore was largely ineffective.

In an attempt to enforce the embargo, U.S. warships and local authorities tried to prevent vessels bearing British and Canadian cargo from landing in Maine’s ports and harbors. Nevertheless, some ports conducted illicit trade with New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. This was particularly true in Eastport, Maine, where at least a dozen merchant vessels might be in the port at any given time.

President James Madison declared war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812. Congress approved the war only by a narrow margin in both houses. Madison’s rationale was that the U.S. armed forces had to go to war to safeguard the freedom of the seas.

Although there were at least a dozen different reasons for going to war against Great Britain, the most glaring was the British practice of impressment. The English did not have enough able-bodied seamen for all of their warships. For that reason, press gangs snatched men from the wharves of the Atlantic and Mediterranean ports. The British also took those seamen who could not prove U.S. citizenship directly from American merchant ships during their searches. It is estimated that the Royal Navy impressed a total of 6,200 American seamen.

One of the most egregious incidents occurred on June 22, 1807, when the HMS Leopard opened fire on the USS Cheseapeake off Norfolk, Virginia. A boarding party from the Leopard took four seamen from the Cheseapeake before departing.

Support for the war was strong throughout the 15 American states except New England where the desire to conduct commerce with Great Britain and Canada outweighed the matter of impressments.

The land war began badly for the Americans; however, the fledgling U.S. Navy gave a good account of itself. Captain Isaac Hull led the frigate USS Constitution to victory off Nova Scotia in a duel with the frigate HMS Guerriere on August 19, 1812, and Captain Stephen Decatur, commanding the frigate USS United States, captured the frigate HMS Macedonian in a sea battle off Portugal on October 25, 1812.

But just three months before the Boxer arrived off the Maine coast, the frigate HMS Shannon defeated the USS Chesapeake on June 1, 1813, in a bloody action outside Boston Harbor. The Shannon’s guns had disabled the Chesapeake within minutes of the start of the contest, and U.S. Captain James Lawrence was mortally wounded by small arms fire as the British swarmed onto the Chesapeake’s deck. The British took their prize to Halifax, Nova Scotia where Lawrence was buried by the British with honors. Six British captains acted as pallbearers for his coffin, one of whom was Blyth.

There were significant differences between U.S. frigates and gun-brigs. For one, frigates had three masts, while brigs had two. Second, American frigates at the outbreak of the war had 24-pounder long guns in their main battery, whereas the brigs had 18-pounder carronades. Carronades were short, smoothbore, cast-iron cannons that fired a heavy shot and required fewer men to handle in action. They were used for short-range contests.

The U.S. Navy had already seen substantial experience by the War of 1812, having fought France in the so-called Quasi War of 1798-1800 and the First Barbary War, also known as the Tripolitania War, from 1801-1805. During the course of the War of 1812, the U.S. Navy would fight 11 single-ship duels with the Royal Navy.

It was natural that Maine would be a theater of war given its close proximity to New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Although Mainers desperately desired statehood, they would not obtain it until 1820. Mainers made their living from lumbering, freighting, and fishing. Each of these activities suffered as a result of the trade embargo with Great Britain. Nearly all of the towns and ports on the Maine coast had written to Jefferson imploring him to lift the embargo.

Blyth had an impressive record at sea. He had been wounded six times and had distinguished himself commanding British vessels in naval combat against Dutch ships. He was disappointed that he was not given a larger ship than the brig Boxer, but England was experiencing a glut of experienced ship commanders, and he was forced to make the best of it with the two-masted gun-brig.

The 180-ton Boxer was a new ship. The Royal Navy launched the Boxer on July 25, 1812, at Redbridge, Southampton. Designed for coastal patrol, the gun-brigs were slow and lightly armed. They were rated at between 10 and 18 guns. They were far less expensive to build than frigates, and the Royal Navy had commissioned as many as 150 at the outset of the War of 1812. The Boxer, which had a crew of 66, mounted 12 18-pounder carronades and two long 6-pounders, as bow chasers, for a total of 14 guns.

The Boxer began its patrol of the Maine waters in early July 1813. In a roughly seven-week period, it captured seven schooners before it encountered the Enterprise. For the crews of the captured American vessels, Blyth offered reasonable terms of ransom and treated detainees with kindness in order to make the ordeal as painless as possible given the circumstances.

When Blyth halted a small boat close to the shore in August, he learned from the three men aboard that the brig Enterprise was being readied at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, for patrol on the Maine coast.

While he was staying in St. John, New Brunswick, before passing into American waters, Blyth met Charles Tappan, a New Hampshire merchant. Tappan was aboard the merchant brig Lacona, which was disguised as the Margaretta, a vessel with Swedish papers, to avoid the U.S. embargo. Tappan and his partner, William King of Bath, Maine, intended to import British wool clothing and blankets into the District of Maine.

Although King was a high-ranking militia officer, he had no intention of allowing his business to suffer as a result of the embargo. The King-Tappan Group was eager to import these items because of the strong demand for them in America from both civilian and military customers. Tappan said that he intended to register the goods at Bath and pay the tariff on them.

Bath was situated on the Kennebec River 13 miles from its mouth. Tappan was fearful that American privateers, which were commissioned to stop and inspect merchant vessels, would discover that the Margaretta was actually an American merchant ship. Because of this, he asked Blyth to escort the Margaretta from Eastport to the mouth of the Kennebec. In exchange for his assistance, Tappan promised Blyth a bill of exchange worth £100 with the group’s London banker. The Margaretta was not ready to depart immediately, but Tappan asked Blyth to keep an eye out for her when she sailed.

After nearly two months at sea, Blyth learned that the Margaretta had sailed for Bath. In early September the Boxer met the Margaretta off Eastport and escorted it southwest toward Bath. At one point, a thick fog engulfed both ships, and the Boxer began towing the Margaretta rather than wait for the weather to improve.

When they reached Seguin Island near the mouth of the Kennebec on September 3, Blyth fired three shots from the Boxer’s guns over the Margaretta. It was part of a mock attack concocted by Blyth and Tappan to deceive any local residents who observed the two ships together into believing that the British warship had attempted to stop the Margaretta.

Blyth decided to stay in the vicinity for the next few days. On June 4, he dropped off four men at Monhegan Island, which was directly south of Pemaquid. He did this in response to a request from local fisherman that the ship’s surgeon attend to a sick resident of the island’s small fishing community. The other three men went ashore to hunt seabirds to supplement the crew’s diet. At that point, Burrows was under sail from Portland.

The Enterprise had a storied history. Originally built as a 12-gun schooner, the U.S. Navy launched it in 1799 from Baltimore. The schooner participated in both the Quasi-War with France and the Tripolitania War. She was modified and rigged as a brig in October 1811 at the Washington Navy Yard.

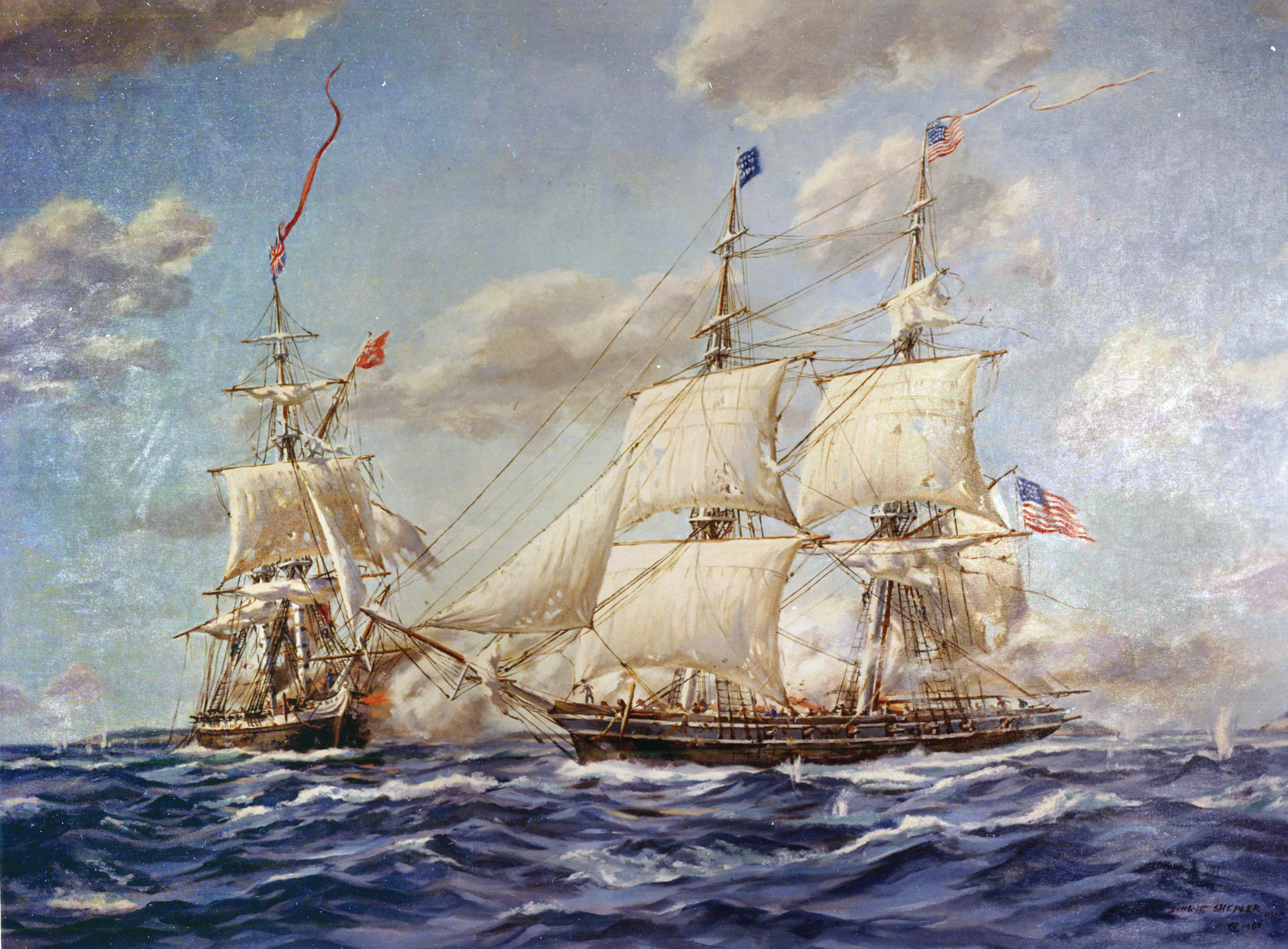

Like many of the other small U.S. warships during the War of 1812, the Enterprise was overloaded and overmanned. Guns were run through her bridle ports, which were the openings on either side of the bow where mooring lines were attached. The brig Enterprise mounted 14 18-pounder carronades and two long 9-pounders for a total of 16 guns. Although it had two more guns than the Boxer, the Enterprise had a much larger crew. The larger crew came in handy during a sea battle because it offered a pool of replacement gunners.

At dusk on September 4, the Enterprise anchored south of Townsend (modern-day Boothbay Harbor), a short distance west of Pemaquid Harbor. The following morning dawned clear, pleasant, and bright with a light wind. When the lookout aboard the Boxerspotted the unidentified ship approaching from the west at mid-day, Blyth raised anchor and set out to confront the vessel. The urgency of the situation did not allow him sufficient time to retrieve the four men on Monhegan Island.

Blyth fired three shots downwind as a challenge to the fast-approaching vessel. Having heard the shots, residents in a half dozen coastal towns and villages in Lincoln and Knox Counties raced to a point where they might be able to see the unfolding action. The British mariners on Monhegan watched as both ships moved farther out to sea in order to have plenty of room to maneuver without fear of striking the hidden ledges prevalent along the rocky Maine coast.

Confident that he could take the Boxer in a head-to-head contest, Burrows ordered the Enterprise’s sails shortened as he tacked toward the Boxer. When he issued orders for his crew to move one of the 9-pounders from the bow to the stern, Burrows heard some of his crew griping that Burrows intended to flee from the British brig. Burrows immediately addressed their grumbling. “We are going to fight both ends and both sides of this ship, as long as the ends and sides hold together,” he shouted. A cheer went up from the crew.

On the Boxer, Blyth ordered his men to nail Union Jacks to both masts, a common practice in preparation for a battle. He then instructed his crew that the flags should not be taken down as long as he was still alive. Blyth said the Boxer would either capture the Enterprise or sink in defeat.

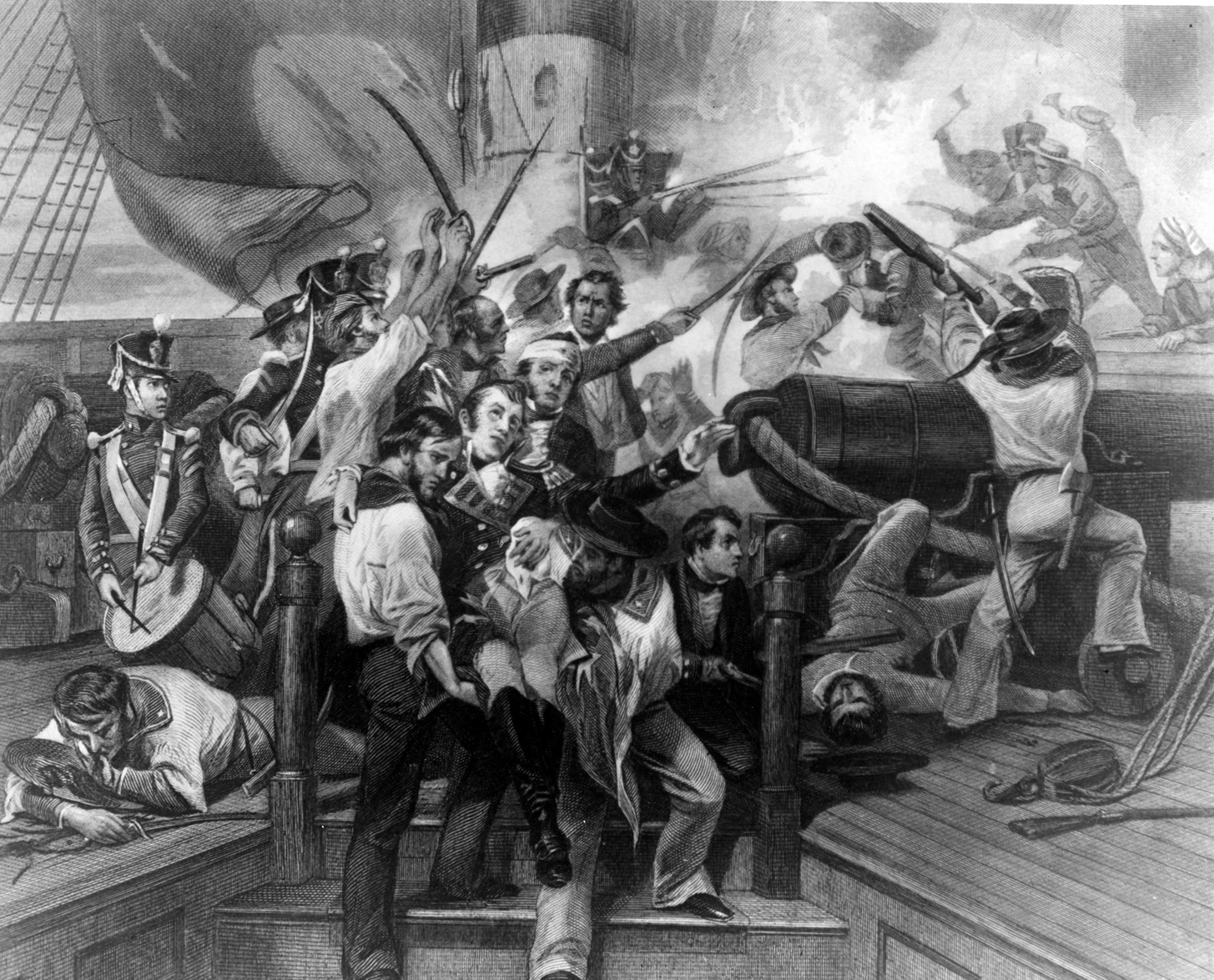

The Enterprise drew close to the Boxer when the two brigs were eight miles southeast of Seguin Island. At the start of the battle, “the contestants ranged and circled in free sea-room between Monhegan and Seguin,” recalled William Barnes, a Mainer serving aboard the Enterprise. At 3:20 pm they were close enough for both crews to fire on each other with small arms. As the Enterprise drew alongside the Boxer on its port side, the crew of the Boxer gave three cheers and then fired a broadside with their starboard guns. Burrows immediately ordered his gunners to fire a broadside in response. The American guns did frightful damage to the Boxer, disabling guns, shredding braces and rigging, and sending deadly wooden splinters spraying through the air.

“Great God, what shots!” Blyth cried out. No sooner had he uttered the words than an 18-pound ball killed him. The ball struck his torso with so much force that he was nearly torn in half. Burrows, who had jumped to replace a fallen gunner on one of the quarter deck carronades, was shot through the groin as musket fire from the Boxer spattered across the deck of the Enterprise. He was taken and laid to rest against a shot rack. The ship’s surgeon, Dr. Bailey Washington (a relative of George Washington), tried to make Burrows as comfortable as possible, but he was bleeding profusely from his severe wound. “Don’t give up the ship!” Burrows shouted with as much strength as he could muster. “We’ll take her yet!”

Command of the Enterprise devolved to Lieutenant Edward McCall. Meanwhile, Lieutenant David McGrery took command of the Boxer. For 15 minutes the two ships traded broadsides with more guns falling out of action with each successive barrage. McCall then shouted for his crew to move their brig forward; as the Enterprise moved forward, the 9-pounder in the stern inflicted additional damage to the Boxer.

The Enterprise then ranged ahead, rounded the enemy vessel on the starboard tack, and raked the Boxer with its starboard guns. Sensing victory, McCall ordered the foresail set to keep the ship moving. The Enterprise then moved to the Boxer’s starboard bow and raked her yet again.

By 3:45 pm, the Boxer was in shambles. The American guns had knocked down both of the Boxer’s masts and shot away the braces and rigging used to control the ship. As a result, the Boxer was dead in the water and no longer manageable. As if that were not enough, the Boxer was taking on water.

McGrery shouted to the Americans for quarters. He then boarded the Enterprise in order to offer Blyth’s sword to McCall; however, McCall told him that he had to present it to Burrows. When he did so, Burrows said that McGrery should keep Blyth’s sword and return it to his family. Burrows succumbed to his wounds during the night.

The Americans suffered four killed and 10 wounded. The exact number of British casualties is unknown because as the Americans took possession of the Boxer, the British were burying some of their men at sea. Nevertheless, it is believed they suffered at least 20 killed and 14 wounded. The Enterprise towed the Boxer to Portland.

The two captains were buried September 9 in a joint funeral at Monjoy Hill in Portland. As the funeral procession wound its way through town, gunners on the Enterprise fired a shot every minute in salute. Burrows’ casket was draped with the 15-star, 15-stripe American flag. American newspapers hailed the Enterprise’s victory as “a brilliant success.” Burrows had succeeded in redeeming the U.S. Navy in the wake of the Chesapeake disaster.