By Arnold Blumberg

On the morning of September 13, 1943, Col. Gen. Heinrich G. von Vietinghoff, commander of the German Tenth Army, faced a difficult decision. He could order his forces to abandon the line with which they contained the Allied landing at Salerno, or he could order them to launch a large-scale counterattack. When he learned that morning that a seven-mile-wide gap existed between the British and American sectors of the Salerno beachhead, Vietinghoff could not resist the impulse to exploit it.

From his headquarters at St. Angelo just north of Naples, Vietinghoff immediately ordered measures to repel the enemy incursion, enjoining his subordinates to make a “ruthless concentration of all forces at Salerno” and drive the Allies into the sea.

German officers barked orders. Veteran troops rushed to get their vehicles and equipment ready. By mid-afternoon tanks, self-propelled guns, and half-tracks of the 16th Panzer Division were clattering toward the U.S. position on the north bank of the Sele River, while elements of the 29th Panzergrenadier Division advanced toward the U.S. position south of the Calore River. Panzer grenadiers marched behind the vehicles singing “Lili Marlene” and shooting flares and fireworks into the sky to deceive the enemy into believing that a massive force was making the counterattack. The two German armored divisions hoped to catch the regiments on the American left flank in a pincer movement and destroy them. Once that was done, Vietinghoff could inform his superior commander, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, that the Germans were on the verge of a great victory.

Operation Avalanche: The Allied Invasion of Salerno

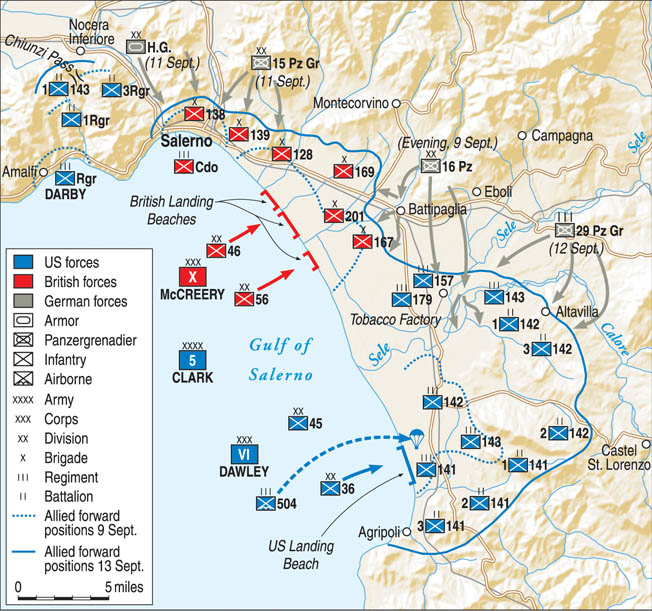

Operation Avalanche, the code name for the Salerno landings to be carried out by Lt. Gen. Mark Clark’s Fifth Army, began in the early hours of September 9, when elements of three Allied divisions, two British and one American, began landing on the beaches south of the small port of Salerno.

The two main components of Clark’s Fifth Army were Lt. Gen. Richard McCreery’s British X Corps and Maj. Gen. Ernest J. Dawley’s U.S. VI Corps. British X Corps was composed of the 46th and 56th Infantry Divisions, which landed five miles north of the Sele. The U.S. VI Corps was composed initially of only the U.S. 36th Infantry Division, which landed at Paestum south of the Sele. A portion of the U.S. 45th Infantry Division was scheduled to reinforce it immediately. To the left of the British, U.S. Rangers and British Commandos landed on the Sorrento Peninsular to block the Germans from reinforcing the battle zone from the direction of Naples.

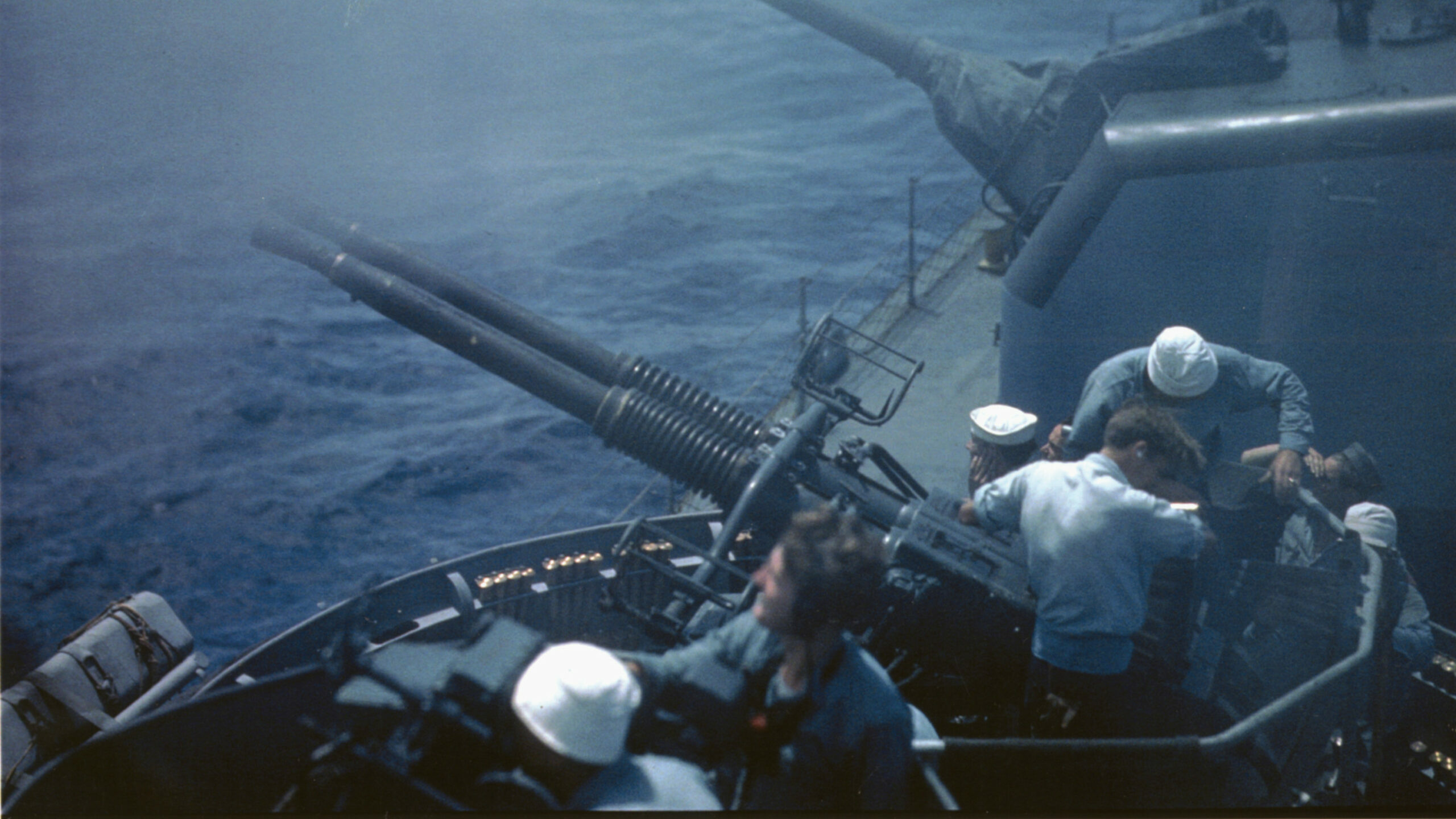

The challenge the Germans faced at Salerno on the first day of the invasion was how to confront the initial Allied amphibious force of 54,000 infantry supported by large numbers of artillery batteries and several battalions of tanks and self-propelled tank destroyers. The Allied armada was composed of 627 troop and supply transports and warships. The U.S. Navy and Royal Navy warships had the capacity to deliver massive and devastating naval gunfire onto the shore in support of the beachhead.

The Allies had approximately 1,000 medium and heavy bombers, as well as 1,400 fighters and fighter bombers flying from bases in Sicily. In addition, one light and four small British escort carriers, fielding a total of 120 aircraft, were present to support the Allied fleet and assault force.

The Allies chose to strike Italy in 1943 for a number of strategic reasons. First, an invasion would most likely force that demoralized country out of the war. Second, the move would take some pressure off the Soviet Union by forcing Germany to redeploy a large number of troops from the front lines in Russia to replace Italian units garrisoning the Balkan region. Third was the need to actively employ the Allies’ vast air, land, and sea forces already staged in the Mediterranean Sea.

The Allies picked Salerno as their invasion site on the Italian mainland because of the excellent approaches by sea to a 20-mile stretch of beach five miles south of the town. The absence of shoals and good underwater gradients permitted ships to come close to land. A narrow strip of sand between water and dune and numerous beach exits leading to the main coastal highway, which led from Agropoli north through Salerno to Naples and eventually to Rome, would facilitate shore operations. Salerno harbor and the tiny port of Amalfi nearby would be helpful in receiving supplies. Coastal defenses in the area, including six fixed shore batteries, were almost exclusively fieldworks rather than permanent installations. What is more, Salerno was within reasonable striking distance of the port of Naples, which the Allies needed as a supply depot to sustain combat operations in Italy.

But there were some serious disadvantages posed by using Salerno as an entry point into Italy. The distance of Salerno from the toe of the Italian boot precluded mutual support by the two Allied invasion forces: the Fifth Army, under Clark, invading by water at Salerno, and Lt. Gen. Bernard L. Montgomery’s 240,000-strong British Eighth Army, which on September 3 crossed from Sicily into Calabria and was moving north up Italy’s west coast. The Sele River, which empties into the Gulf of Salerno 17 miles south of Salerno and divides the coastal plain, split the Allied invasion forces. The coastal plain was flat, low lying, and bisected by many irrigation ditches, drainage canals, and fences and walls.

The steep vertical banks of the Sele and its principal tributary, the Calore River, which paralleled the Sele until joining it four miles from the sea, hampered maneuver and communication between McCreery’s forces north of the river and Dawley’s forces south of the river.

The flat coastal plain was ringed by mountains just 10 miles inland from the beaches. The presence of mountains so close to the shoreline exposed the attackers to enemy observation, fire, and assault from higher ground. The main ridgeline in the area, which was the rocky spur of the Sorrento Peninsula, blocked access to Naples except for two narrow gorges that pierce the ridge. All told, the prospects for the success of Operation Avalanche were mixed. The Allies would have to contend not only with the terrain disadvantages but also with an enemy that was determined to do its best to hurl the invasion force back into the sea.

Veteran German Defenders Await the Allied Attack

As they waited for the Allies to press their attack on the Italian mainland, the German high command and the German commanders in Italy debated the best strategy for the Italian Theater. On the one side, the German high command advocated abandoning all of Italy below the Po Valley. On the other side, Kesselring, the commander of all German forces in southern Italy, argued for defending Italy south of Rome. Kesselring was heavily engaged at the time with the continued disarmament of the Italian Army after its surrender to the Allies on September 7.

Facing the Allies along the entire invasion front were 15,000 men belonging to the 16th Panzer Division of Generalleutnant Hermann Balck’s XIV Panzer Corps. The 16th Panzer Division, which was led by Generalmajor Rudolf Sieckenius, had been partially destroyed at Stalingrad the year before, but the Germans had rebuilt the unit around its core of 3,400 veterans from the original division. Contrary to Vietinghoff’s orders, Balck did not move directly to Salerno; instead, he halted 10 miles north of the port. As a result, the 16th Panzer Division fought alone on September 9, absorbing the full force of the invasion.

Having taken over their area of responsibility only hours before, Sieckenius and his men had made the most of their limited time to prepare to defend the coastline. In addition to manning the six Italian shore batteries between Salerno south to Agropoli, they placed artillery and mortars in a semicircle covering the whole shoreline. Artillery spotters took posts on the high ground surrounding the invasion site, enabling the Germans to direct fire on the gulf, the beaches, and the plain. For direct defense of the beaches, the Germans used the division’s 105 tanks and 36 assault guns in small groups, sometimes supported by a platoon of infantry, to stage attacks and keep the enemy off balance and thus slow his progress inland.

In addition, the Germans laid antipersonnel Teller mines randomly 15 yards from the water’s edge in a belt extending 100 yards inland. Eight strongpoints containing machine guns, infantry, artillery, and antitank guns protected in the front and rear by barbed wire were sited to cover likely landing points. For the first several days of the invasion, German ground forces enjoyed the support of their brethren in the Luftwaffe, who conducted upward of 450 sorties against the Allies on the beaches.

The Battle For Salerno: A Back & Forth Battle

By the end of day one of Operation Avalanche, as a result of Allied naval gunfire and the support of field artillery, much of the enemy fire covering the beachhead had been destroyed and losses in men and armored vehicles due to German action were relatively light. However, the anticipated advance inland by the Allies fell far short of expectations. Although the Allies had hoped that by the end of the first day the beachhead would be 4,000 yards deep, in most places it was only 400 yards deep.

Avalanche planners had thought a beachhead line taking in Salerno, Battipaglia, Eboli, and Ponte Sele would be reached by the close of the first day. The X Corps was supposed to have linked up with VI Corps, and the battle line would then continue through the mountains beyond Altavilla and Albanella to include Monte Soprano and Monte Sottane. This line would have given the invaders ample room to maneuver on the beaches and would have provided commanding positions over the entire beachhead, thus giving the Allies a firm base from which to advance on Naples.

Due to the efforts of the German defenders, however, the actual line the Allies held after dark on September 9 ran three miles southeast of Salerno, about two miles inland, and back to the coast four miles short of the Sele River mouth. The VI Corps had moved from the beach and taken the town of Cappacio, and a unit of the 36th Division was nearing capture of Monte Sottane. However, on the corps’ right flank the landing area was still under fire, and American soldiers there were pinned down. Moreover, three of the most desirable objectives of day one, Montecorvino airfield, Salerno harbor, and Battipaglia, were not taken from the Germans.

Kesselring endorsed Vietinghoff’s decision on September 10 to fight at Salerno by directing Generalmajor Eberhard Rodt’s 15th Panzergrenadier Division and Generalleutnant Paul Conrath’s Luftwaffe Panzer Division Hermann Göring, both of the XIV Panzer Corps, to move toward Salerno. The field marshal also released Generalleutnant Fritz-Hubert Graser’s 3rd Panzergrenadier Division to move south from Rome to Salerno.

At the same time, Generalmajor Smilo Freiherr von Luttwitz’s 26th Panzer Division and Generalmajor Walter Fries’ 29th Panzergrenadier divisions, both of which belonged to Generalleutnant Traugott Herr’s LXXVI Panzer Corps, having disengaged from Eighth Army’s front, raced north to Salerno.

Vietinghoff moved the 16th Panzer Division out of the American sector to the British sector of the battlefield. He hoped the 29th Panzergrenadier Division’s anticipated arrival would allow that unit to contain the U.S. VI Corps while the XIV Corps attacked the British X Corps. By the second day of Operation Avalanche, the Germans had managed to concentrate the bulk of their forces in the area against the British, thus barring the most direct route to Naples.

The X Corps sent out probes against these new enemy dispositions early on September 10. Progress was negligible due to heavy concentrations of enemy artillery fire expertly directed from spotters on the mountain range to the British front and strong German counterattacks. The 56th Division opposite Battipaglia took the heaviest punishment. After penetrating into the town, its soldiers were first pounded by artillery barrages and then driven out by tanks and infantry from the 16th Panzer Division. Another German tank attack between Battipaglia and Montecorvino airfield, at the tobacco factory, drove elements of the 56th Division’s 201st Guards Brigade back toward the beach.

On the far left flank of VI Corps in the American sector, the 179th Regimental Combat Team of the 45th Division sustained heavy casualties as it advanced to the Calore River but was still able to secure the destroyed bridge at Ponte Sele. On the American right flank, battalions from the 142nd RCT of the 36th Division advanced from Paestum toward Hill 424 and captured the town of Altavilla. A counterattack by 25 German tanks was repulsed with the help of naval guns and field artillery. During the course of the day, the division’s beachhead was extended with the capture of Monte Soprano. Throughout this period massive Allied naval gunfire proved critical in supporting the advance, defense, and retreat of the British and American ground combat units against relentless German counterattacks.

The following day, September 11, the pattern of seesaw combat seen on September 10 continued. In the American sector the fighting around Ponte Sele was unrelenting as German armored thrusts forced the Americans to give up some ground near the bridge, which the Americans had repaired, and at Calore. That same day, the 142nd RCT was stopped cold by enemy attacks directed at Altavilla.

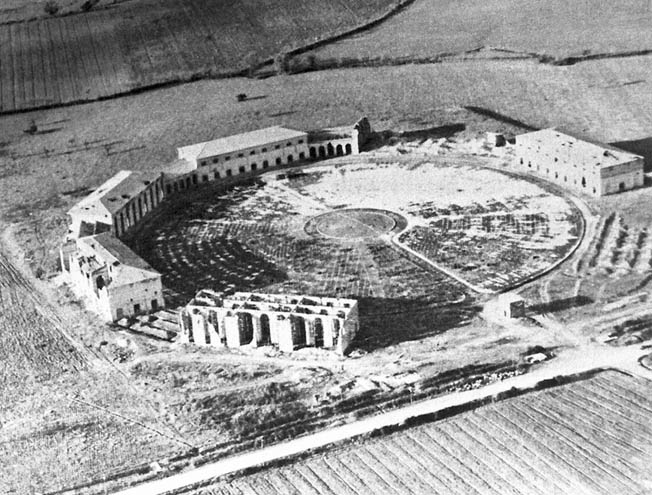

On the X Corps front the most intense fighting involved the batle for Battipaglia, and the tobacco factory. After elements of Brig. Gen. Julian Gascoigne’s 201st Guards Brigade penetrated the town, they were flung out by a violent German tank attack. Another attempt to take the Tobacco factory was crushed by German panzers with many British killed and captured. By day’s end, the British held only a toehold in Battipaglia.

To the north of the beachhead, the Commandos and Rangers passed the day under increasing pressure as Kesselring’s reinforcements stiffened the defense of the passes leading to Naples.

By the end of the third day, the Allies had expanded their foothold and occupied the port of Salerno. But the port facilities were so heavily damaged that they could not be used by the Allies. In the American zone the beachhead had been pushed 10 miles inland, while the British foothold was only one mile deep. Clark remained optimistic about the possibility of his forces soon being able to clear the Germans from the Sorrento Peninsula. Once that was done, they could advance directly on Naples.

September 12 saw the Germans mount strong attacks along the entire beachhead as reinforcements continued to arrive, albeit piecemeal, from both northern and southern Italy. At the southern end of the beachhead, attacks on the left of VI Corps were made by elements of the 16th Panzer and 29th Panzergrenadier Divisions. In the area around Montecorvino, the Germans made concerted attacks on the British X Corps.

In all sectors the Allies had a tough time warding off these determined assaults and in many instances were forced to retreat. The 45th Division, which had set out in two columns toward Ponte Sele was threatened with an enemy encirclement. To prevent this, Clark trnasferred the division’s 157th RCT, which had gone to the British sector, to the Sele area to protect the flank of its parent division as it advanced northward. The regiment was hit by German tank and machine-gun fire from the high ground around Persano and from the tobacco factory after the Germans had crossed the Sele and occupied those two sites. (This tobacco factory was not the complex of warehouses of the same name previously mentioned in the British area of operations.) The intense enemy fire knocked out seven tanks accompanying the 157th RCT and stopped the outfit in its tracks. Even worse, the ground held by the Germans formed a threatening wedge in the weakly held seam between the British and American beachheads.

The fighting around Persano and the tobacco factory swung back and forth throughout the day. A ground attack by the 45th Division, which was supported by naval gunfire from the cruiser USS Philadelphia, eventually cleared the Germans from those two vital locations.

In the afternoon a battalion of the 142nd RCT lost Altavilla and Hill 424 after being pummeled by artillery fire and assaulted by elements of the 15th Panzergrenadier Regiment. At Battipaglia, the 56th Division was pushed out of the small part of the town it held and retreated 3,000 yards to the southwest to form a new line of defense.

Clark had come ashore early in the morning and established his headquarters in the VI Corps area. As he toured the battlefield and took in the situation, he recounted later that he felt the landing force had gotten itself into a bind and was at risk of being driven into the sea.

For this reason, Clark considered transferring the U.S. VI Corps north to the British X Corps’ zone. He eventually dismissed the idea. Indeed, to attempt a major redeployment of his forces in the face of an aggressive opponent would have been an invitation to disaster. Clark decided that if the Germans were going to push the Allied Fifth Army off the beach they would have to do it one step at a time. The next day it looked as if the Germans were going to do exactly that.

Black Monday

By mid-morning on September 13, Vietinghoff had chosen a bold course of action. He was aware of the gap between the American and British sectors and wrongly concluded that the Allies had deliberately split themselves into two sections in preparation to evacuate the beachhead.

Having arrived at that erroneous conclusion, Vietinghoff looked at other evidence, misconstrued its significance and adopted it to support his theory. He believed that additional ships had arrived in the Gulf of Salerno to assist with the evacuation. He also believed Allied smokescreens around Battipaglia on the British right flank were intended to cover the British withdrawal. Sensing victory, Vietinghoff wanted not just to drive the Allies from their beachhead but also to prevent their escape. Kesselring endorsed his plan to attack. “The invaders in the area Naples-Salerno and southward must be completely annihilated and, in addition, thrown into the sea,” said Kesselring.

The British Eighth Army was still days from joining the Fifth Army at Salerno. Skillful delaying actions by German rear guards, demolition of roads and bridges in the path of Montgomery’s force, and the Eighth Army’s lack of bridging equipment had slowed its northward advance. On September 12, the Eighth Army was still 80 miles from Salerno; it would not make contact with the Fifth Army until September 16.

From the American point of view, the German efforts on September 13, which became known afterward as Black Monday, were at first less a concerted attack than a sharp increase in resistance. An example of this was the stalled attack by the U.S. 36th Infantry Division against Altavilla and nearby Hill 424. Both attacks encountered stiff resistance.

The failure at Altavilla was overshadowed by near disaster in the Sele-Calore corridor. The 2nd Battalion of the 143rd RCT, after having relieved the 179th RCT, set up a defense two miles northeast of Persano and three miles from Altavilla, while the 157th RCT was two miles to the rear covering the Persano crossing of the Sele from its north bank. As a result, both of the 2nd Battalion’s flanks were in the air, and the Sele-Calore gap was undefended. Meanwhile, Vietinghoff, supported by Herr, more than ever believed that the Allies were preparing to embark. At 2:30 pm he directed his XIV Corps to assemble all available forces for an attack south of Eboli to disrupt the supposed enemy withdrawal.

An hour later, 20 German panzers, an infantry platoon, and a few pieces of towed artillery left Eboli and moved toward the tobacco factory just north of the Sele held by the 1st Battalion, 157th RCT. As shells slammed into the American position, six German tanks attacked the battalion’s left while 15 more struck the battalion’s right. Although the Americans fired artillery and antitank guns at the Germans, the Germans routed the 1st Battalion. The Germans continued their advance and captured the Persano crossing and the tobacco factory.

Having uncovered the crossing of the Sele, the Germans entered the Sele-Calore corridor and struck the left rear of the 2nd Battalion, 143rd RCT. Meanwhile, more German armor advanced to Ponte Sele and cut the battalion’s right flank. Barely hindered by the weak defense of the American infantry and light American artillery fire, the Germans overran 2nd battalion capturing 500 men.

At 5 pm the Germans held undisputed control of the corridor. They placed artillery near Persano and sent 15 tanks toward the juncture of the Sele and Calore Rivers. Within an hour German tanks and infantry stood on the north bank of the Calore. The only Americans between the Germans and the sea were the 158th and 189th Field Artillery Battalions of the 45th Infantry Division. Just 200 yards behind them was Fifth Army’s command post.

Upon seeing the enemy on the north shore of the river, the American batteries, positioned on a gentle slope overlooking the corridor, opened fire at point-blank range while headquarters personnel formed a battle line on the southern bank of the river. Tank destroyers of the 636th Tank Destroyer Battalion, 36th Division, just coming ashore, rushed to aid the gunners. Finding the situation extremely critical and realizing that the American forces might sustain a severe defeat in the area, Clark arranged to send his staff by boat to the British sector. Shortly after the Germans penetrated the Sele-Calore gap, Clark received a call from Dawley, who asked him what he planned to do about the worsening situation. “Nothing,” said Clark. “I have no reserves. All I’ve got is a prayer.”

In the X Corps sector, units were overextended. Conrath’s Panzer Division Hermann Göring near Vietri threatened to cut communications between the X Corps and the Rangers to the north. But the VI Corps predicament south of the Sele was the most precarious. Clark called a meeting of his senior commanders at 7:30 pm and announced that plans to evacuate the American beachhead were being made. While the Americans discussed the looming crisis, Vietinghoff informed Kesselring of his troops’ successes. “After a defensive battle lasting four days, enemy resistance [is] collapsing,” wrote Vietinghoff. “Tenth Army pursuing on wide front. Heavy fighting still in progress near Salerno and Altavilla. Maneuver in progress to cut off the retreating enemy from Paestum.”

Thirty minutes later, Herr told Vietinghoff that he doubted the Allied front was crumbling. Herr pointed out that enemy resistance was stiffening and American tanks were countering the German attacks. Vietinghoff refused to believe Herr’s news. He urged his corps leaders to press the attack. Meanwhile, Balck also was skeptical of an impending Allied defeat. As a result, he failed to attack on September 13 with the newly arrived battlegroups from the 15th and 3rd Panzergrenadier Divisions; instead, he opted to make more preparations and then strike the next day.

Fifth Army found itself on the brink of defeat by nightfall on September 13. This was mainly because it could not build up the beachhead as fast as the Germans who could insert reinforcements by land faster than the Allies could by sea because of an acute shortage of transport ships. The question remained that night whether Fifth Army could hold the beachhead.

As night approached on September 13, near where the Sele and the Calore Rivers met, less than five miles from the shoreline and a stone’s throw from Highway 18, men of the 158th and 189th Field Artillery Battalions stood along with a handful of tanks and tank destroyers and Fifth Army headquarters’ personnel, formed into makeshift infantry units in an effort to hold the most critical portion of the VI Corps front. Against a company of German tanks and a battalion of infantry, the Americans had fired more than 3,600 artillery rounds in four hours. Another 300 shots were fired by the newly arrived 27th Armored Field Artillery Battalion. The artillery fire, coupled with tank and tank destroyer fire from the base of the corridor, stopped the German penetration. With no immediate reinforcements available, the Germans pulled back to Persano at nightfall.

The Allies Strengthen Their Position

For the Americans, the situation remained precarious due to the lack of infantry needed to counter the enemy threat. The 1st Battalion, 142nd RCT was almost destroyed at Altavilla. The 2nd Battalion, 143rd RCT stationed in the Sele-Calore gap had ceased to exist. The 3rd battalions of the 142nd and 143rd RCTs had lost heavily at Altavilla, while the 157th RCT’s 1st Battalion had been mauled at the tobacco factory.

Because of these circumstances, American commanders decided to shorten the American line. The 45th Division refused its right flank by moving parts of the 157th and 179th RCTs back along the Sele. The 1st Battalion, 179th joined the defenders at the base of the corridor, holding the junction of the Sele and Calore. In the center of the VI Corps line, the 36th Division drew back two miles to La Cosa Creek, while 1st Battalion, 141st RCT positioned itself on Monte Soprano and 2nd Battalion of that regiment took station near the corps’ left, immediately south of Highway 18. The VI Corps’ extreme right was entrusted to a battalion of the 531st Engineer Regiment. The 3rd Battalion, 141st RCT and an engineer detachment guarded the corps’ left flank. Remnants of the depleted battalions chewed up at Altavilla made up a general corps reserve. The new defensive line was dug in, mined, and held at all costs.

On Clark’s request, immediate help was sent to the American beachhead in the early hours of September 14 when two battalions of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, U.S. 82nd Airborne Division, were dropped near Paestum and then trucked to Monte Soprano on VI Corp’s right.

The Germans also adjusted their positions during the night of September 13-14. One regiment of Luttwitz’s 26th Panzer Division went into line that evening near Eboli. Since its armored regiment was on detached service near Rome and one of its battlegroups was still retarding the progress of Eighth Army, the 26th Panzer Division could only contribute one regiment to the fight at Salerno. Vietinghoff ordered Luttwitz to take over the northern portion of the 16th Panzer Division area and attack toward Salerno. The hope was that the fresh 26th Panzer Division would be able to break through the British lines and make contact with Panzer Division Hermann Göring, which was scheduled to strike Vietri and then Salerno.

As these plans were being formulated, Balck informed his army commander that the British were fighting hard to regain the heights west of Salerno near Vietri. He argued that unless the Germans could cause more trouble in the Sele-Calore gap, no large-scale attack near Vietri or between Salerno and Battipaglia would be feasible. Despite the pessimistic but more realistic views of his corps commanders, the Tenth Army leader demanded that the XIV Corps and LXXVI Corps attack.

German pressure on September 14 against the British was at first centered on Salerno, where the 46th Division, dug in on the hills around the town, put up a determined defense. The Germans shifted their attack to the Battipaglia area where the 56th Division fought tenaciously on the open ground in full view of its opponents. It received effective aid in the form of friendly naval gunfire and aerial bombing, which pummeled the Germans along the Battipaglia-Eboli road. By the end of the day, the British held firm. “Nothing of interest to report during daylight,” reported McCreery.

In the American sector on September 14, the Germans attacked with eight tanks and a battalion of infantry from the 16th Panzer and 29th Panzergrenadier Divisions at 8 am. Moving from the tobacco factory the attackers came up against the newly aligned 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 179th RTC. Working in tandem, American tanks and artillery pummeled the German flanks. American aircraft and naval gunfire also harried the Germans as they advanced. After all the German tanks were destroyed, the panzergrenadiers withdrew.

During mid-morning, close to the river a company of infantry and six tanks advanced toward the 1st Battalion, 157th RCT and 3rd Battalion, 179th RCT. Effective fire, including many naval salvos, threw the Germans back. The Germans launched two more attacks against elements of the 45th Division, but they both failed to budge the Americans. German attacks against the 36th Division met the same fate. When a company of German infantry supported by tanks tried to cross the Calore River, U.S. artillery fire shredded them. Throughout the rest of the day, heavy land- and sea-based artillery barrages kept the Germans at bay. By nightfall on September 14, the VI Corps was in firm command of its position. Altogether, the Americans had knocked out 30 enemy armored fighting vehicles.

By the evening of September 14, the Allied position at Salerno had vastly improved. The seam between X and VI Corps southeast of Battipaglia had been stitched together with friendly units. Just as important, the British 7th Armored Division had arrived in the X Corps zone, and the 180th RCT, 45th Division came ashore to form a reserve force near Monte Soprano. In addition, 2,100 paratroopers from the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division dropped at Paestum.

On September 14, Vietinghoff slowly realized that his chance to drive his enemy into the sea was slipping away. Furthermore, Kesselring told him that regardless of whether the Tenth Army defeated its opponent it was to begin gradually withdrawing toward Rome. Nevertheless, Vietinghoff was still free to try one more time to dislodge the Allies from Salerno.

Having been given one more opportunity to try to defeat the Fifth Army, Vietinghoff decided to use the 26th Panzer Division in an attack northwest from Battipaglia to Salerno while Panzer Division Hermann Göring advanced from Vietri to Salerno. Because of these new orders, the brunt of the German attacks of September 15 fell on the British 46th Division. These were not as intense as on the previous days, but the British were at times hard pressed.

Two battalions from the 26th Panzer Division lost 90 men killed and wounded in an advance that gained only 200 yards. The 3rd Panzergrenadier Division maintained close contact while the 16th Panzer Division was ordered to continue the assault that night. When it did renew its attacks on the morning of September 16, the fighting was as brutal as any that occurred during the battle. The 9th Panzergrenadier Regiment launched its attack in the Battipaglia region against units of the 56th Division. The British and Germans fought hand to hand on the British perimeter, but the strength of the British defenses and the overwhelming Allied firepower drove the panzergrenadiers back.

After seeing the results of the fierce fighting, Vietinghoff realized on September 16 that he could not vanquish the U.S. Fifth Army. He therefore asked Kesselring for permission to withdraw; it was granted on September 17. Orders to leave the Salerno area were issued soon afterward, and Germans units began withdrawing from their positions the following day. The Germans left small units behind to ward off any enemy pursuit. The bulk of the German Tenth Army shifted to its right and headed for the Volturno River, where it entrenched and waited for the Allies.

A Clumsy Victory For the Allies At Salerno

The week-long Battle of Salerno had cost the British and Americans a total of 2,349 killed, 7,366 wounded, and 4,100 missing. The Germans lost 840 killed and 2,000 wounded. A large number of the German casualties were the result of Allied field artillery and naval gunfire.

For the Allies, Operation Avalanche had been a success despite the fact that American troops often lacked that measure of aggressiveness shown by their adversary. German commanders pointed out that the U.S. troops in particular displayed hardly any tactical imagination and missed opportunities to exploit weaknesses in their opponent’s situation. But the Allied troops, clumsy and lacking finesse, fought tenaciously on defense and exploited their immense artillery and air assets.

As for the Germans, they had fought well in every respect throughout the Salerno Campaign. During the battles around the Allied beachhead, the Germans had undertaken a series of impressive moves. They responded rapidly to threats, conducted lightning-fast maneuvers, and carried out concentrated attacks and timely counterattacks, despite the massive artillery and air superiority enjoyed by their enemy.

The fight around Salerno in September 1943 initiated a brutal, 19-month battle for control of Italy. The tenacity shown by the Germans was no match for the overwhelming resources of the Allies. Despite the tactical awkwardness of the Allied forces engaged at Salerno, they had managed to establish themselves in force on the Italian mainland. More hard fighting loomed ahead, but the Allies were determined to defeat the Germans, even if it meant a heavy price in casualties.

Great