By Louis Ciotola

In the late 14th century, a new and seemingly irresistible force was emerging in the East, the likes of which Europe had not seen for centuries. The Ottoman Empire fought wars for one purpose only—the constant expansion of the Turkish state. Western Europe, by contrast, could scarcely have been more different. Littered by a patchwork of feudal territories with only the slightest hint of royal influence, Western Europe was not only divided and in nearly constant conflict, but behind the times militarily. Its rulers and knights still saw war primarly as an exercise in personal glory rather than a national means to a greater end. The old crusading spirit was still alive and well in Europe in 1396.

The Turkish threat to Europe began at mid-century when Ottoman Sultan Murad I led his armies across the straits from Asia. His unremitting conquest of the Balkans ended abruptly in 1389 at the Battle of Kosovo, where he was killed following a great victory over the local Christian powers. Murad’s son and successor, Bayezid I, called an urgent halt to the campaign. For the Ottomans, Europe was still a backwater, and after the death of his father the new sultan needed to consolidate his crown on the critical Asian front before considering a return to the West.

Bayezid’s absence did not go unnoticed. Rival Hungary, alongside its fickle ally Wallachia, took advantage of the sultan’s distraction to invade his vassal state, Bulgaria. For King Sigismund of Hungary, his success lasted only as long as his enemy was away. In 1392, Bayezid returned with a vengeance and quickly turned the tide back in Turkish favor. First, he resecured Serbia as his vassal, granting it a privileged position within his empire to assure its future loyalty. Then he swept back through Bulgaria, driving clear to Vidin on the Danube, near the Hungarian frontier. Sigismund began to feel notably uncomfortable with the Ottomans on his doorstep.

Bayezid, however, had no desire to cross the Danube. Instead, he used the mighty river as a barrier to protect his gains while he pursued his true ambition—the conquest of Constantinople. For centuries, the once powerful Byzantine Empire had been in decline. Bayezid was determined to put it out of its misery by taking the capital city. In May 1394, the Turks surrounded Constantinople and began a siege.

The siege went on for only a few months before Bayezid again was distracted, this time by the necessity of invading Wallachia. For the first time, things did not go entirely as he planned. Despite being outnumbered four to one, the ruler of Wallachia, Mircea cel Batrân the Elder, stood his ground and checked the Turkish advance. The subsequent Ottoman withdrawal left the river flowing with blood from a great army of corpses, according to one Bulgarian chronicler. The remarkable victory saved Wallachia not only as an independent state, but as a future ally for Hungary. Bayezid took out his frustrations by sacking the Bulgarian city of Nicopolis and beheading Ivan Shishman, the last ruler of a truly independent Bulgaria.

Upon Bayezid’s return to Constantinople, the question was not if the city would fall, but when. The siege bedeviled embattled Byzantine Emperor Manuel II. Nearly as concerned was Venice, which feared the consequences of Ottoman expansion on its lucrative Mediterranean trade. As a result, the Venetians urged Manuel to seek Western assistance. Closer to home, King Sigismund, facing the Ottomans on the Danube as well as enduring domestic turmoil, was increasingly receptive to Manuel’s pleas. He forged alliances with the Byzantine emperor and, in an effort to spark a new crusade, sent envoys to various parts of Europe, warning of the deadly Turkish threat to Christianity.

At the time, Western Europe was enjoying a brief period of peace due to a truce between France and England in the never-ending Hundred Years’ War. Consequently, warlike knights needed a new outlet with which to display their martial talents. Europe had never quite gotten over the crusading spirit, even though five years earlier a coalition led by France and Genoa had failed disastrously against the Hafsid kingdom of Tunisia. These factors made a crusade against the Turks ever more attractive. Victory in the Balkans might propel the Christian army all the way back to the Holy Land and everlasting glory.

A steady stream of outrageous rumors fueled hysteria and created fertile ground for Sigismund’s pleas. Fears emerged that the Turks planned to invade Austria and, wilder still, France. France’s mad king, Charles VI, paid especially close attention to the threat, while in a rare display of solidarity, both Pope Boniface IX in Rome and Pope Benedict XIII in Avignon issued crusading bulls complete with promises of absolution.

Far and away the most influential proponent of a new crusade was Duke Philip of Burgundy. An uncle of King Charles, “Philip the Bold” had dreamed of personally leading a crusade for most of his life. Although military glory was undoubtedly on his mind, Philip also believed that a triumph against the Turks would catapult his family into a position of increased royal favor. He had actively pushed Sigismund in the past to call on France to participate in a crusade. At long last, the Hungarian king gave him what he so desperately desired.

Before traveling to France, Sigismund’s ambassadors stopped in Venice to secure the critical support of the dominant European maritime power. Already partial to the scheme, the Venetians offered to assist with a flotilla of galleys. At the same time, the Hospitaller Knights of Rhodes eagerly donated a fleet as well, desperate to relieve their own dire predicament with the Ottomans. Later that spring, Hungarian envoys arrived in Lyon for a much anticipated audience with Philip.

The Hungarians could not have found a more enthusiastic supporter. Although now too old to campaign personally, Philip promised to fund the crusade and appointed his 24-year-old son, Jean de Nevers, as the Franco-Burgundian leader. Following a brief stop in Bordeaux, the envoys next traveled to Paris, where excitement was equally intense. Because the king was suffering from one of his frequent bouts of madness, his regents spoke on his behalf, affirming the monarch’s approval of the endeavor. The knights and nobility of France supported the decision as well, and many stepped forward to claim their own spots in the high adventure that lay ahead.

Nevers’s appointment was little more than a political gesture; his actual power was limited. At that point, the would-be leader of Christian Europe had never participated in a single battle. Small in stature and clumsy in appearance, the closest Nevers had come to combat was the occasional tournament. Philip kept his son on a short leash, never entrusting him with any significant responsibility. Nevertheless, all reservations took a back seat when the honor of Burgundy was at stake.

No one was more thrilled by his king’s acquiescence in a crusade than the Constable of France, Philip of Artois, Count d’Eu. An ardent crusader, d’Eu had participated in the failed campaign in Tunisia in 1390. He had twice traveled to Hungary, first in 1388 during a pilgrimage to the Holy Land that ended with his imprisonment in Egypt, and then in 1393 to offer his services against the Turks to Sigismund. Much to the knight’s dismay, Sigismund turned him down, instead requesting that d’Eu campaign against the troublesome Bohemian heretics. The cold welcome did not stop d’Eu from bringing home exuberant stories that whetted the martial appetites of his fellow knights and the king. A frequent presence at court, he was a man Charles believed he could trust.

Another influential French nobleman was Jean le Meingre. When he was only 16, Meingre was dubbed a knight on the field of Roosebeke in 1382. Nine years later the king promoted him to Marshal of France. The new Marshal Boucicaut’s exceedingly rapid rise made him impatient and overly aggressive. He too was an experienced crusader, in Prussia and Spain, and he had traveled east in 1388 to pay d’Eu’s ransom to the Sultan of Egypt.

Even more admired by French knights for his military and political wisdom was the aged Enguerrand VII, Lord of Coucy, whose career stretched back four decades to the peasant uprising of 1358. In his long career, Coucy had learned valuable lessons on ambush and raiding and had come to understand that simply charging forward in the traditional passionate frenzy was rarely the best maneuver. He sharpened his diplomatic skills when, as a brief hostage in England, he struck up an acquaintance with King Edward III. Later, he commanded a papal army in Italy and, like many of his contemporaries, served notably at Roosebeke and in Tunisia.

Jean de Vienne was another older knight who had earned his king’s respect. As Admiral of France since 1373, Vienne had reorganized the French navy during the long war with England, becoming famous for conducting daring raids along the English coast. Like most of his contemporaries, he had distinguished himself against the Flemish at Roosebeke, but by far his most memorable feat was the Scottish expedition of 1384. After successfully transporting an army to Scotland, Vienne attempted a bold invasion of northern England, but after a few minor victories he was forced to withdraw. The new French king, Charles VI, was not a naval enthusiast, so Vienne transferred his energy to crusading in the Tunisian campaign. Although his naval background would hardly be useful in Eastern Europe, both Charles and Philip nevertheless expected Vienne to strengthen the upcoming campaign with his invaluable advice.

A knight known less for his military reputation than for his individual valor, Jean IV de Carrouges first commanded troops under Vienne against the English in Normandy in 1380. Four years later he again served Vienne as part of the ill-fated Scottish adventure, during which he obtained his knighthood. Carrouges was most famous for the duel he fought with a longtime rival, Jacques Le Gris. When his wife told him that Le Gris had raped her while he was away on campaign, Carrouges was given the opportunity to personally settle accounts with his enemy. The event, which took place in December 1386, became part of Parisian lore. After an unsuccessful mounted joust witnessed by the king and much of the nobility, Carrouges dispatched Le Gris on foot with his sword. As memorable as that noble display was, it was his prior experience with Vienne that earned Carrouges a welcome place in the coming crusade.

Philip of Burgundy took it upon himself to contribute the funding for the Franco-Burgundian element of the crusade. At the same time, a number of German noblemen also raised troops, most notably Burgrave John III of Nuremburg and Count Palantine Ruprecht Pipan. The English too had been petitioned by the Hungarians but declined to participate in the upcoming campaign. The only English planning to participate were those already serving the Hospitallers on Rhodes.

The Duke of Burgundy had his work cut out for him. Even a man as wealthy as Philip found the cost of funding a crusade to be daunting. He dispatched Nevers to Flanders to gather the necessary revenue, but when that proved to be insufficient Philip was forced to initiate a second wave of taxation; over the course of the next year he raised some 700,000 gold francs. Philip felt no restraint on how he spent it. Practicality, as it turned out, was not a priority. Lavish tents and pavilions were constructed for the knights, along with banners and standards embroidered in ivory, silver, and gold. Nevers added to the pageantry with his own glittering contingent of 150 knights, while Boucicaut brought 70 more. In all, about 1,000 Franco-Burgundian knights joined the crusade. A few thousand more soldiers of all classes assembled for the adventure.

Philip was not so foolish as to believe that his son could actually direct the expedition. Fortunately, the knights accompanying the young man had plentiful experience, and from among them the duke selected a council of advisers, including Vienne, to guide Nevers and make the most important decisions. He also created a secondary council including Coucy, d’Eu, and Boucicaut. Philip would have liked Coucy to take a more prominent role, but the old knight demurred on the grounds that it would be an offense to the admiral, constable, and marshal, all of whom outranked him. Still, the duke urged his son to pay special heed to Coucy’s wisdom.

As the army gathered in Dijon in the early spring of 1396, one last task remained. The lead knights, conscious of their chivalric duties, drew up a strict code of conduct for the crusade to maintain their piety and Christian virtue. The code included such punishments as decapitation for drawing a dagger and severing an ear for theft. But the code only applied within the actual crusading army itself. Should the knights wish to degenerate into barbarians when fighting the Turks, no one was prepared to object.

The Franco-Burgundian army, joined by a handful of Spaniards and Italians, departed Dijon in April 1396. Nevers met it at Montbéliard to take command. Meanwhile, Coucy led a smaller force by a different route through Lombardy, having been delegated by Charles to negotiate with Milan on an unrelated topic. Speculation existed later that Coucy had inadvertently alarmed the Sultan to the West’s intentions. But the Venetian-Hospitaller fleet, commanded by Master Philibert de Naillac, made no attempt to blockade the Bosporus or Dardanelles, indicating that Bayezid and his army were already on the European side of the Danube. This was most likely attributable to the ongoing siege of Constantinople rather than advance knowledge of the crusade.

The main crusader army stopped at Regensburg to merge with the German contingent and feast with Albert of Bavaria, who insisted on holding a celebration in its honor. As the representative of his influential father, Nevers could hardly refuse the invitation, even though it delayed the campaign. D’Eu and Boucicaut continued with the vanguard to Vienna, where once again Nevers was toasted upon his arrival, this time by Duke Leopold IV of Austria. No one questioned the propriety of such diversions.

Upon their arrival in Buda, the crusaders were greeted by Sigismund, who supposedly promised them that together they would soon throw the Turks out of Europe. In truth, Sigismund was intelligent enough to know that such a prospect was impracticable. He feared an Ottoman invasion and thought the best strategy would be one of cautious advance, if not defense. The crusaders did not share that sentiment. They considered Bayezid a coward who threatened to invade but was nowhere in sight. Reconnaissance soon verified that Sigismund’s fears of an invasion were groundless—the Ottoman army was not in the area. As the most experienced diplomat among the Franco-Burgundians, Coucy was their designated spokesman. “Though the Sultan’s boasts be lies,” he told Sigismund, “that should not keep us from doing deeds of arms and pursuing our enemies, for that is the purpose for which we came.”

The crusaders had far more ambitious plans than simply pursuing their enemies. Many entertained fantasies of marching all the way to the Holy Land. When Sigismund proposed a campaign through Transylvania and Wallachia to shore up his reluctant allies, the knights rejected it adamantly. Only a direct route, they said, would prove their courage and virtue. The army, which now included French, Burgundians, Hungarians, Germans, Spaniards, Italians, Poles, and Bohemians, would soon be joined by Transylvanians, Wallachians, and the Venetian-Hospitaller fleet.

The crusaders set out from Buda to face the Ottoman Turks with the Constable of Hungary, Nicholas de Gara, commanding the vanguard and Nevers accompanying Sigismund in the rear. The Christian army traveled east along the northern bank of the Danube until reaching the Derdap gorge near the town of Orsova. The gorge, nicknamed the Iron Gate due to the sudden narrowing of the river, took a full eight days to cross. Most of the ships, which carried the army’s provisions, successfully navigated the gorge and continued downstream. Finding themselves among a largely Orthodox population, the crusaders’ discipline began to markedly deteriorate, although their previous behavior in Catholic areas had hardly been exemplary.

The first town with a Turkish garrison in the path of the crusading army was Vidin. It took only the slightest show of force to prompt Bulgarian Prince Ivan Stratismir to open the city gates and capitulate, after which the crusaders proceeded to butcher the small number of Turks inside. Although less a real battle than a senseless massacre, the occasion was deemed heroic enough to allow for the official knighting of Nevers.

Thanks to the imprudence of the Christian army, the next town in its path understood that surrender was not an option. Behind two walls and a moat, Oryahovo and its determined Turkish defenders prepared to fight to the last man. The knights blindly trusted their own invincibility. Led by d’Eu and Boucicaut, they attempted to storm the town without even bothering to inform Nevers, much less Sigismund. After gaining the bridge over the moat at a cost of nearly 500 men, the crusaders’ attack sputtered out at the base of the walls, at which point the Hungarian king had no choice but to come to their aid. With the mass of the Hungarians pressing forward, the garrison offered to surrender.

According to the terms, the defenders would only lay down their arms if the attackers promised to spare Oryahovo a general massacre. Sigismund quickly agreed to the conditions but was soon to see just how uncontrollable his allies could be. Claiming all provisions to be null and void because crusader blood had already been spilled in the capture of a minor portion of the ramparts, the crusaders went on to soil the king’s name by violating the surrender terms and slaughtering the inhabitants. Apart from 1,000 nobles selected to be ransomed, no quarter was given. The campaign had barely begun, and an insulted Sigismund was already second guessing the wisdom of having beseeched the flower of European chivalry for help.

But with the towns along the march growing ever more formidable, it was no time to be squeamish. The next target was Nicopolis, key to the Danubian arteries flowing south into Bulgaria. Like Oryahovo, it too was double-walled, but there the similarities ended. Nicopolis had the added benefit of being built on a plateau and defended by a strong and well-equipped garrison commanded by Dogan Bey, one of the sultan’s most loyal commanders.

For once, the crusaders abstained from an immediate assault and settled in for a siege. Equipped with illustrious banners rather than catapults or siege engines, success could not be expected in the near future. The army began constructing ladders, towers, and mines on the landward side of the town for an eventual attack, while the 44 galleys of the Venetian-Hospitaller fleet, which arrived via the Danube on September 10, blockaded the river side.

True to form, the crusaders entertained themselves throughout the brief siege with drunken festivities. In an almost unbelievable act of self-delusion, Boucicaut decreed that anyone who spread the rumor that the cowardly sultan would fight would have his ears cut off. Despite the order, Bayezid was indeed fast on his way to confront them.

The sultan had been informed days earlier of the crusaders’ approach. Fortunately for him, his army was already in Europe conducting the siege of Constantinople. Intercepting the Christians was merely a matter of packing up and heading north. As the Turks marched northward, their numbers grew, gaining contingents at Philippolis, followed by the army of their Serbian vassal, Stephen Lazarovic, at Tarnovo. It was there that a Hungarian reconnaissance party first detected the Turks’ advance.

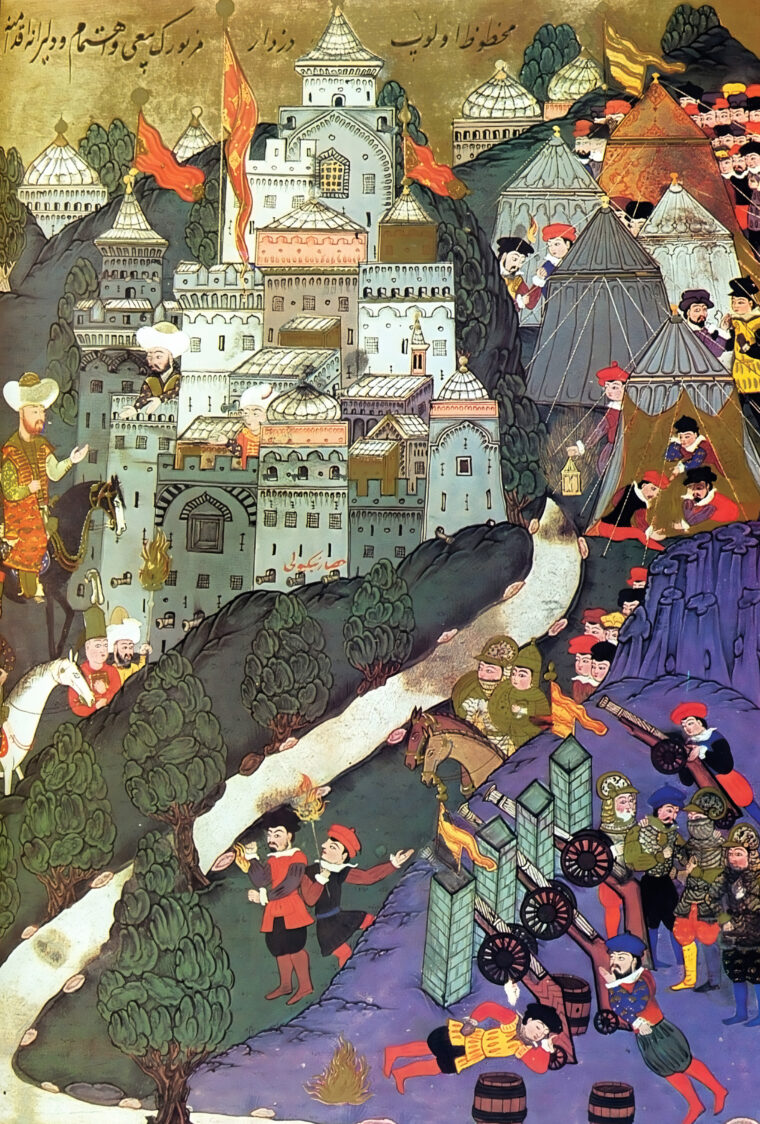

On September 24, the sultan arrived outside Nicopolis. According to the Ottoman chronicler Nesri, he stealthily approached the walls alone and spoke to Dogan Bey. “Hang on bravely,” he said. “I will look after you. You shall see that I will be here like a flash of lightning!” It was a fitting legend to attribute to a man nicknamed the Thunderbolt.

Bayezid’s arrival prompted at least one knight to hurriedly pull himself away from the revelries. Upon learning of an isolated Turkish detachment, Coucy assembled 1,000 horsemen and crossbowmen to wipe it out. The Turkish detachment, which was probably a reconnaissance force led by Everenos Bey, had positioned itself within a narrow defile. Utilizing tactics that were utterly alien to his fellow knights, Coucy teased the Turks with a body of 100 cavalry until they were tempted to emerge. Feigning retreat, the cavalry led the Turks forward into a trap. The victory was complete, but rather than earning the respect of his compatriots, Coucy was accused by d’Eu and others of robbing Nevers of his rightful glory. The episode proved an ill omen of future discord.

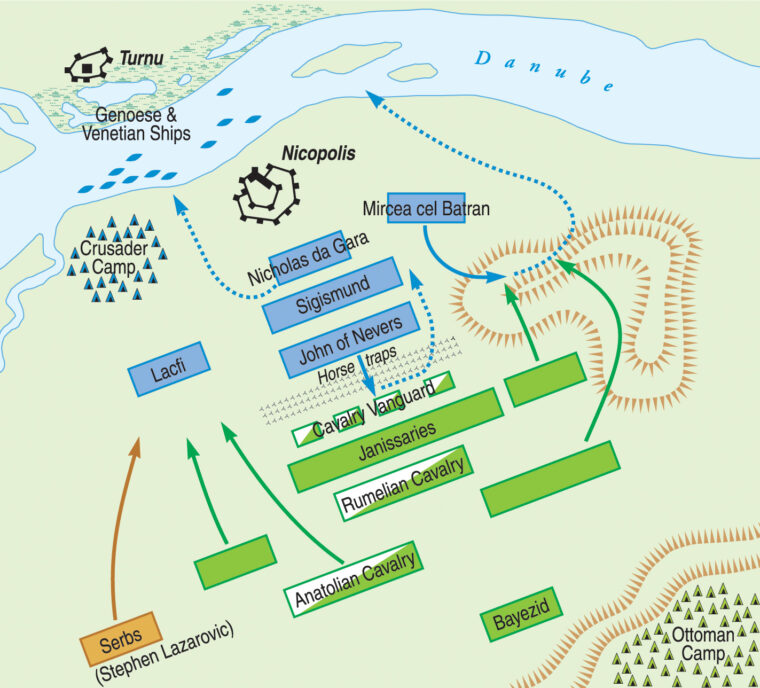

It became clear that a general battle would soon be fought against the main Turkish army. Sigismund wasted little time in suggesting how it should be conducted. The Hungarians and their eastern allies, having extensive experience fighting the Turks and understanding their tactics, recommended a defensive engagement, fearing the enemy would attempt a ruse to draw the overly aggressive knights into a trap. To avoid that, Sigismund reasoned, the heavily armored knights should be kept back until the last moment to deliver the coup de grace to an exhausted enemy. In the meantime, he would march the shaky Transylvanians and Wallachians forward to ensure that they remained loyal, while his Hungarians followed closely behind.

The king’s argument was sound. The older knights supported the plan, especially Coucy, who was familiar with the Wallachians and their often treacherous ways. The Wallachian voivode Mircea had deep reservations about the battle, feeling that the knights made war as if it were a game. For him and his people, war was not a sport but an unfortunate necessity forced upon them to preserve their independence amid aggressive neighbors. As Sigismund suspected, Mircea also distrusted the Hungarians, whom he believed to be every bit as menacing to Wallachia as the Ottomans.

Unsurprisingly, Vienne’s and Coucy’s endorsements of Sigismund’s tactics were met with scorn at a council of war with their fellow knights. “The King of Hungary,” said d’Eu, “wishes to have the flower and honor of battle.” In their eyes, Vienne and Coucy were nearly treasonous. The Franco-Burgundian knights, the younger men insisted, must take the lead in battle. Honor and privilege demanded it; anything less would be pure cowardice. Philip had hoped that his son would pay heed to the wisdom of the older warriors. Instead, when his intervention was most critical, Nevers concurred with the opinion of the headstrong majority.

Having rejected Sigismund’s advice, the Franco-Burgundians, joined by a portion of the Germans, placed themselves in the vanguard of the Christian army. Some distance behind were the Hungarians and Hospitallers, commanded by Sigismund and Naillac, respectively. Mircea’s Wallachians assembled to the right of the Hungarians, while the Transylvanians, led by Stephen Laczkovic, formed on the left.

Unlike the Christians, there were no disputes within the Ottoman ranks. Bayezid was familiar with Nicopolis and knew the local terrain well—not that anyone would have dared to challenge his judgment anyway. As Sigismund correctly surmised, Bayezid hoped to bait the enemy forward before enveloping it with his wings and annihilating it. To achieve this goal, he occupied a slight hill to the south of the town. On the slope of the hill, fully visible to the Christians, he placed his irregular cavalry, or akindji, whose apparent weakness was meant to entice the crusaders forward. Behind the akindji were the irregular infantry, or azabs, and the Janissaries, a newly created entity. Additionally, the Turks erected a thick row of stakes in front of the infantry to thwart the anticipated cavalry charge.

If all went as planned, the killer blow would be delivered by Bayezid’s favorite weapon, the mailed lancers, or Sipahis. He kept the Sipahis along with Lazarovic’s Serbs concealed behind the hill and prepared to strike at the critical moment. The coming battle was shaping up to be a classic contest between strength and agility.

Before dawn on September 25, Sigismund made a last desperate attempt to avoid the calamity he foresaw all too clearly. Visiting the crusader camp, Sigismund pleaded that they observe due caution. As before, Vienne and Coucy concurred, but they were unable to sway Nevers, who reportedly begged the king to permit the knights to attack. Since the knights did not require Sigismund’s permission, it was unlikely that Nevers felt the need to put on such a shameful display. Chronicler Jean Froissart provided a more likely account when he claimed that d’Eu, infuriated by Sigismund’s attempt at persuasion, roared that anything short of an immediate charge would “expose us to the contempt of all!” At that point, Vienne was said to quip, “When truth and reason cannot be heard, then must arrogance rule.” Nonetheless, as senior commander, the admiral agreed to lead the crusaders into battle.

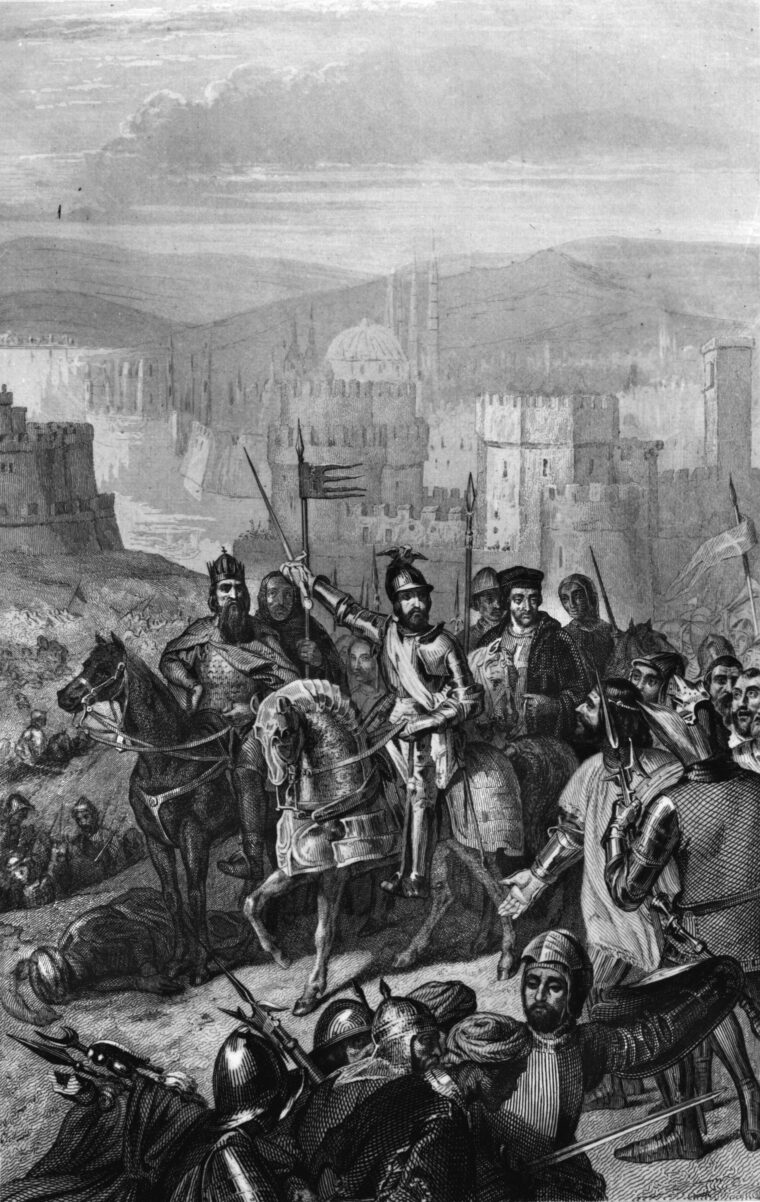

Before the attack began, an episode transpired that was to have the most dreadful of consequences. Perhaps fearful of providing the garrison of Nicopolis with a reason to launch a sortie, or else simply immersed in a frenzy of prebattle blood lust, the knights massacred the remaining prisoners from Oryahovo and left the bodies for all to see. Then the crusaders mounted up for the attack. The Hungarians, possibly unaware that the battle was commencing, remained static in their original position as their allies began to trot forward. Building up steam, the knights plunged into a headlong charge with cries of “Vive Saint Denis!” and “Vive Saint Georges!” Seconds later they crashed into the Turkish irregular cavalry, violently punching a hole through it. The akindji had time to fire only a few volleys of arrows before they were divided, after which they regained composure and fell back around both flanks to reassemble behind the infantry as planned. Their losses were heavy, but as a body they remained intact.

Much to their surprise, the knights next encountered the line of stakes, which were sharpened and fixed to drive into the breast of any horse that might charge forward. But the horses were not suicidal and came to a screeching halt before the menacing spears. With the crusaders temporarily immobilized, Turkish infantry began pouring arrows into them, aiming primarily at the horses as the lightweight projectiles were largely ineffective against thick armor. At that point, the knights had little choice but to dismount and continue on foot. Boucicaut declared a death from arrows to be cowardly and bravely led his men forward, uprooting the stakes as they went.

The result was a foregone conclusion. The Turkish foot was simply no match for the Westerners, whose steel armor stopped sabers and maces cold while their own heavy axes and swords hacked right through the lightly clad Ottomans. Within minutes, Turkish losses mounted at a feverish pace. Without hesitation, the knights charged through and scattered the reconstituted Turkish cavalry for a second time. Their momentum seemed unstoppable.

Even Bayezid was confused by what was transpiring. He had successfully baited the Christian army but did not anticipate that the enemy would simply slash through his front lines as though they were made of paper. It was then that the overwhelming success of the knights became their undoing. Rather than halt and consolidate the victory, d’Eu and Boucicaut pressed the charge in the mistaken belief that they had completely destroyed the Ottoman army. Up the hill the crusaders climbed until, reaching the summit, they were utterly exhausted. Only then did they glimpse the fresh Sipahis, ready to strike. The sultan’s strategy had paid off.

Upon catching sight of the Sipahis, a monk of St. Denis recounted of the knights, “The lion in them turned into a timid hare.” As the Sipahis furiously charged forward, many of the knights fled, cutting off the pointed ends of their shoes to facilitate their escape. Most, however, chose to meet death heroically, including Nevers, d’Eu, Boucicaut, Coucy, Vienne, and Carrouges. The combat was intense. Vienne, bearing the banner of Notre Dame, lost hold of his precious possession six times before it permanently fell to the ground beside his dead body. His longtime comrade Carrouges fell beside him, having fought a last, losing duel with an anonymous Turkish soldier amid the dust and confusion of battle.

Nevers nearly met the same fate but was saved at the last moment when his retinue surrounded him and agreed to put down their arms in return for his life. When the remaining knights saw that he had been captured, they immediately followed suit. Their last hope of avoiding captivity and dishonor lay with the Hungarian king, whom they had only so recently mocked and insulted.

A stampede of horses racing back to their lines without riders alerted Sigismund of the rout. Turning to Naillac, he said, “We lost the day by the pride and vanity of these French.” Both Mircea and Lazarovic agreed. Feeling it foolish to squander their precious soldiers in a lost battle, they promptly exited the field to prepare for the inevitable Turkish invasion of their homelands.

Sigismund, however, was not prepared to concede, believing that there was still time to rescue the crusaders and turn the tide. Leading the Hungarians forward, the king trampled over those Turks already broken by the crusader charge. Moments later, the Hungarians were among the Sipahis and managed to fight the elite cavalry to a standstill. Then Bayezid threw in his last reserves, sending Laczkovic and his mounted Serbs to tip the balance. The Hungarians battled tenaciously until their king’s banner fell, at which point Naillac urged Sigismund to flee the field.

The Hungarian retreat quickly turned into a catastrophe. Panicked soldiers scattered in every direction. Those who were not cut down or captured headed toward the Danube and attempted to pack onto the waiting ships. Badly overcrowded, many of the boats capsized, sending their passengers to a watery grave. Others tried to swim the river only to be weighed down by their armor and drowned. Sigismund managed to board a vessel and set sail. Fearing a Wallachian ambush, he decided to head for the safety of Constantinople rather than attempt a return to Buda.

The number of dead littering the field of Nicopolis was tremendous. Thousands died on both sides, with the Turks getting the worst of it. The scene broke the sultan’s heart. When he visited the site and saw his fallen soldiers, Bayezid vowed that he would not leave their blood unavenged. Grief turned to blind rage when the sultan discovered the bodies of the massacred Oryahovo prisoners. There would swiftly be retribution.

Early the next morning, Bayezid ordered the 3,000 captured Christians gathered together in small groups. Wishing to ransom the wealthiest knights, he enlisted Jacques de Helley, who had served in his father’s eastern campaigns, to act as translator and identify the crusader nobility. In this way, Nevers, d’Eu, and Coucy were saved from the coming carnage but forced to stand beside the sultan and observe the gruesome proceedings. Bayezid then ordered the condemned prisoners stripped and executed.

All those above the age of 20 were decapitated; the rest became slaves. When it came time to behead Boucicaut, Nevers fell to his knees before the sultan and pleaded for the other man’s life. Pressing his thumbs together to indicate that the two men were like brothers, he succeeded in convincing Bayezid that Boucicaut would earn a hefty ransom and thus saved him from death. It was an ironic episode for one who would go down in history as John the Fearless.

Another crusader who escaped execution because he was only 16 later said, “Blood was spilled from morning until vespers.” By nightfall even Bayezid had seen enough and ordered the killing stopped. The remaining 300 prisoners were made slaves. Nevers, d’Eu, Boucicaut, and Coucy fared only marginally better than the average prisoners, being stripped of their clothing and force marched to Gallipoli. From the wounded and worn out from the brutal march, fell ill. In February 1397, the old knight succumbed. A short time later, d’Eu followed him to the grave.

The fate of those French who escaped death or capture at Nicopolis was scarcely better. The winter trek was a misery, and when they finally reached France their tribulations continued when King Charles ordered them imprisoned for spreading “rumors” of defeat. Only after Helley arrived in Paris on Christmas Eve, having been released by the sultan to act as a messenger, did Charles accept the terrible news and release the unfortunate captives.

Loaded down with gifts for the sultan, Helley led an effort to negotiate the remaining prisoners’ ransom, which Philip of Burgundy had agreed to shoulder. The ransom came to over 200,000 gold florins, only a small portion of which could be paid at the time. Nevertheless, Bayezid, busy with the resumed siege of Constantinople, agreed to release Nevers, Boucicaut, and some of the others in June 1397, on the promise that they would travel no farther than Venice until the balance of the ransom was paid in full.

Nevers and Boucicaut fulfilled their oaths and did not return to France until February 1398, at which time they received a hero’s welcome. There was no talk of revenge. Upon their release, Bayezid had pompously dared the knights to challenge him again, but only Boucicaut would ever return to the East. Instead, four years later the Central Asian warlord Tamerlane delivered Bayezid a lethal blow, inadvertently doing Western Europe a huge favor.

Boucicaut would again be taken prisoner after the French defeat at Agincourt in 1415. Six years later he died in England. Meanwhile, Nevers succeeded his father as Duke John of Burgundy in 1404. After a tumultuous 15-year rule full of plotting and murder, his crimes finally caught up to him in 1419. His death was largely unmourned.

Thomas, Duke of Gloucester, summed up the story of the crusaders’ disaster at Nicopolis and the outdated spirit of chivalry that led to their demise. “Those frivolous French got themselves thoroughly smashed up in Hungary and Turkey,” he said. “Foreign knights and squires who go out and fight for them don’t know what they are doing, they couldn’t be worse advised. They are so over-brimming with conceit that they never bring any of their enterprises to a successful conclusion.” So it had been at Nicopolis.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments