By William E. Welsh

The hot sun beat down on the mud-brick and wooden buildings, the lush orchards, and the patchwork of pastoral fields around the oval-shaped, walled city of Damascus in southern Syria on the morning of July 24, 1148. The dome of the Umayyad Great Mosque in the center of the great city reflected the sun like a brilliant diamond. On that day, the strategic metropolis had become the front line of the war between the Frankish crusaders, who had controlled the coast of the Levant for half a century, and the forces of the expansive Seljuk Empire that controlled Persia, Iraq, and Syria. Long columns of crusaders, consisting both of knights and sergeants on horseback and others on foot, moved forward at a measured, determined pace as they pressed their attack on the suburbs west of the city. Whether mounted or on foot, each of the Frankish crusaders clutched a large, kite-shaped shield to protect him from the withering fire of Muslim arrows.

A half century earlier, their predecessors had fought their way to Jerusalem, and in a great feat of arms captured the city from the infidel. The generation of crusaders marching on Damascus that morning drew inspiration from the heroes of the First Crusade, and they hoped that their heroic and glorious deeds, undertaken in God’s name, would one day as well be inscribed in Latin chronicles for posterity. Although physically exhausted and weary from their long journey to the Outremer (Crusader States), their eyes flashed and sparkled when they spoke with each other of the gold, silver, and jewels they hoped to soon plunder from one of the richest cities in Islam.

The devout crusaders had no doubts as to the resilience of their foe, though, and had a keen appreciation for both the professional and irregular Muslim troops that they would fight in the narrow streets and alleys of the suburbs and city. They were painfully cognizant that the urban setting gave the Muslims, who excelled in ambush and hit-and-run tactics, an advantage that would have to be overcome with the brute force inherent in the mail armor, lance, and sword that were the stock and trade of Christendom’s holy warriors. Despite the hurdles in their path to the heart of the city, they remained confident that they could successfully carry it by assault.

Under the leadership of the Frankish and Norman lords who were the senior leaders of the First Crusade, the Latin crusaders had succeeded in securing Jerusalem for Christendom through a well-executed siege against its Egyptian Fatimid defenders in 1099. The 13,000 crusaders who besieged the Holy City of Jerusalem benefitted from the weakness of the Fatimid garrison, which they outnumbered. For the next several decades, the Franks tried to consolidate their holdings on the Levantine coast, as well as push inland; however, it proved difficult to advance into Syria against the powerful Seljuk Turks operating from their secure base at Mosul in the Tigris Valley.

The Seljuk Turks, who were an Oghuz Turkic nomadic people from Central Asia, had invaded the cultivated lands of Persia and Iraq in the 10th century. Sultan Tughril officially founded the Great Seljuk Empire in the 11th century, capturing the Abbasid capital of Baghdad. He relegated the Abbasid Caliphs to state figureheads responsible only for religious matters, and he merged the caliphate’s armies with his own forces. Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan, his successor, won a decisive victory over a Byzantine army in 1071 at Manzikert in eastern Anatolia.

By the time of the First Crusade, the Great Seljuk Empire included Mesopotamia and most of the Levant. Other Turko-Persian states controlled various parts of the Anatolian peninsula, also known as Asia Minor. The Seljuk Sultanate of Rum held sway over eastern and central Anatolia, while various smaller Turkic principalities controlled eastern Anatolia.

In the first quarter of the 12th century, the Muslim emirates of Aleppo and Damascus suffered from instability and weak rulers. As they were under the control of the Seljuk Sultan, they required a frequent infusion of manpower and strong military leadership dispatched by the atabeg (governor) of Mosul.

Seljuk Sultan Mahmud II had appointed Imad al-Din Zengi to serve as the atabeg of Mosul in 1128. A handsome Turkish warlord with flashing eyes, he was resourceful, ruthless, and opportunistic. Seeing an opportunity to take direct control of Aleppo, he did so without asking the Seljuk sultan for permission. Zengi’s watchword was cruelty. He sewed terror throughout the region against his foes, his rivals, and even his subjects. By annexing Aleppo, Zengi carved out for himself a small Seljuk state, but remained faithful to the Seljuk Sultan in Baghdad.

Of the four crusader states established at the time of the First Crusade, Zengi targeted the County of Edessa. It was an inviting target because of its location in Upper Mesopotamia, where it was surrounded by Turkish lands on three sides. Although he detested the Franks, he was just as willing to wage war against the Sunni Muslim emir of Damascus. Once he secured control of Aleppo, he began to try to pluck from the vine of Damascus strategic towns such as Homs, Hama, and Baalbek.

Muin al-Din Abu Mansur Anur, a Mamluk Seljuk Turk, had seized power in Damascus in April 1138. He held the office of atabeg of Damascus, while the weak emir of the Burid Dynasty remained in power as the nominal ruler of the Emirate of Damascus. In September 1139, Zengi besieged Damascus; however, he was unwilling to bombard it because he did not want to inflict heavy damage on the sacred Islamic city, for Damascus, with its Umayyad Mosque, was the fourth-holiest site in Islam. Instead, he periodically attempted to carry it by storm. Anur, knowing that he needed reinforcements, convinced King Fulk of Jerusalem to come to his assistance on the grounds that Zengi also posed a major threat to the northern half of Fulk’s kingdom. When Fulk arrived outside Damascus with a large force of Franks, Zengi raised the siege and withdrew east to Mosul to plot his next move.

Zengi succeeded, though, in capturing the Frankish-held city of Edessa in December 1144. News of the disaster reached Western Europe six months later. Pope Eugenius III was bogged down at the time in the tumultuous politics of the Italian peninsula, but he proclaimed a crusade through a papal bull issued on December 1, 1145.

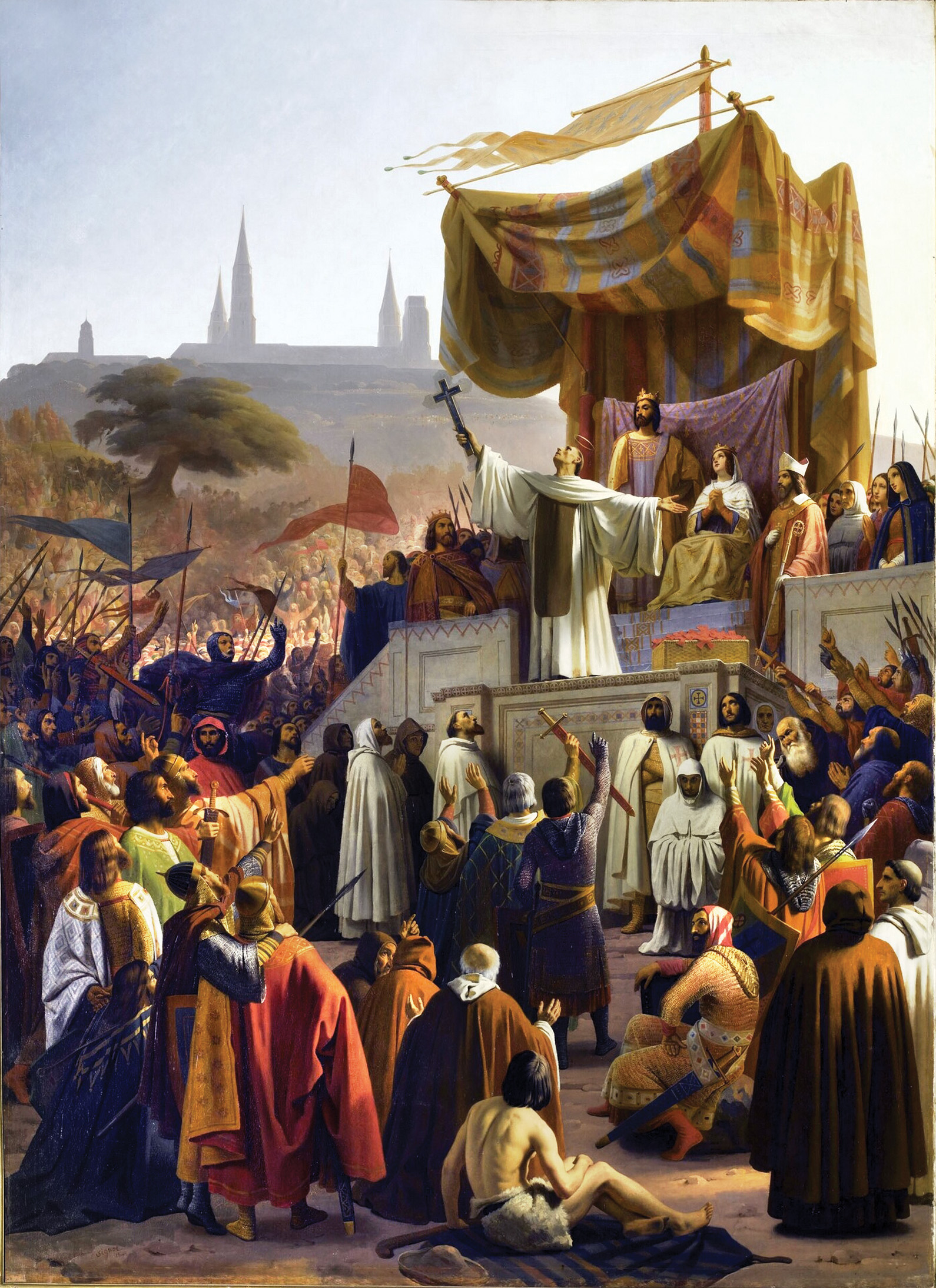

Eugenius left the recruiting and organization of the crusade to Burgundian Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux, who embarked on a grueling seven-month tour that began in August 1146 to preach the crusade. A large force would be essential if there were to be any hope of recovering Edessa, because the leaders of the Latin crusader states were stretched thin just trying to protect their frontiers and garrison their cities.

Damascus was a so-called “oasis city.” With its headwaters in the Anti-Lebanon Mountains, the Barada River flowed southward for 50 miles to Damascus. The river turned east as it neared Damascus and flowed past the northern walls of the city. Since ancient times, farmers had carved out channels in the ground at various levels parallel to the main branch of the river to divert its flow. The irrigation canals created fertile zone that stretched five miles west and northwest of the city, creating a sizeable oasis in which the residents grew fruits, vegetables, and nuts.

An invading army approaching from the west would have to fight its way forward along narrow pathways through the densely planted trees and crops. Making matters worse, many of the local farmers had constructed two-story wooden towers that allowed them to keep close watch on their fields, and these would serve as defensive outposts in the coming battle.

Zengi did not live long to enjoy his conquests for very long. While besieging Qualat Jabar in northern Syria on September 14, 1146, a Frankish slave murdered him in his sleep. Zengi’s heirs divided up his federation. His eldest son Sayf al-Din Ghazi took control of Mosul, and his second son Nur al-Din installed himself as the atabeg of Aleppo.

Whereas a handful of ambitious barons had led the First Crusade, it became clear early on that one or more kings would lead the Christian warriors who would participate in the Second Crusade. Twenty-five-year-old King Louis VII of France already had planned to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and the new crusade catered to his ambitions. Royal France in the mid-12th century consisted of little more than the counties surrounding Paris, because nearly all of western France belonged to the Angevin king of England. Louis made the savvy decision to term the Frankish crusaders who would serve under him the French royal army, which would serve to boost his stature at home and abroad. His participation was noteworthy, for it marked the first time in three centuries that a French king would embark on a foreign expedition.

Although he was initially reluctant to participate in the crusade, intense ecclesiastical pressure on German King Conrad III compelled him to take the cross as well in order to lead a German army of crusaders. With Italian politics stabilized to a degree, Pope Eugenius traveled to Paris in spring 1147 and participated in a ceremony in June outside the city at the Royal Church of St. Denis, in which he presented his pilgrim staff to Louis as the French monarch prepared to set out for the Holy Land. His wife, French Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, would accompany him on the crusade. Louis then raised the Oriflamme, which was a pointed, blood-red banner on a gilded lance that was stored at St. Denis. The Oriflamme served as the king’s royal banner, and it was believed to have served as Charlemagne’s battle standard.

Meanwhile, Conrad had embarked with the German crusaders from Regensburg in May. After the ceremony at St. Denis, Louis traveled to Metz, where he took charge of the northern French army and set off in late June. They planned to march overland through Anatolia in the same fashion as their predecessors of the First Crusade. The two monarchs had tentatively agreed to join forces once they had crossed the Bosphorous in order to overpower the Seljuk warriors of the Sultanate of Rum. The Seljuks of Rum had learned in the First Crusade that they could not fight a pitched battle on even terms with the heavily armored Franks. For that reason, they had fought smaller crusader armies that had passed through Anatolia in subsequent years primarily with hit-and-run tactics to weaken them. The Seljuk horse archers bided their time and looked for opportunities to encircle and destroy the vanguard or rearguard of a column of crusaders marching through their territory.

Conrad’s German army reached Constantinople in mid-September 1147, and Louis’ French army arrived in the Byzantine capital in early October. The German king became impatient and set off without waiting for Louis to reinforce him. The crusaders had a choice at the outset of three southeastern routes through Anatolia to Antioch. The first and most direct route began in Nicea and passed through Dorylaeum, Iconium, and Tarsus. A second route followed the coastline south to Ephesus and then east through the Meander Valley through Laodicea to Iconium and Tarsus. The third route deviated from the second route by turning south from Laodicea and then east to Antalya and Tarsus.

The German king led the cream of his army on the northernmost route, which guaranteed he would face strong resistance from mounted Turks of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum. Although the Byzantine-Seljuk frontier lay 125 east of Laodicea, Turks routinely raided deep into Byzantine territory in western Anatolia.

Beginning on October 25, the Seljuks began a series of mounted attacks on Conrad’s troops. Unfamiliar with Turkish tactics, the crusaders could not come to grips with the fast-moving Seljuk horse archers. Conrad was wounded by arrow fire in one of the clashes. Having lost thousands of soldiers, Conrad returned to Nicea in early November.

King Louis’s French army followed the middle route. Louis placed the baggage train in the center of the army, where it was protected by mounted knights in the vanguard and rearguard. A Seljuk force, operating inside Byzantine territory, sprung an ambush in the Meander Valley on January 1, 1148, but the crusaders soundly repulsed the assault.

When the Turks in the floodplain attacked the vanguard as it was crossing the river, the knights in the lead charged out of the water, up the steep bank, and overtook the Turkish horse archers before they could scatter. They succeeded in killing a substantial number of Turks while suffering only minor losses. The successful defense of the French column on the march depended on the vanguard and rearguard staying close to the baggage train to protect it. If the vanguard or rearguard became separated, the Turks could easily exploit the situation by attacking the separated unit and the exposed baggage train.

Having received reliable intelligence that Sultanate of Rum Sultan Masud had assembled a combined Seljuk-Danishmend army on the western frontier of his territory at Konya, Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos sent messengers to warn King Louis. But after discussing the matter with the other leaders of the crusader army, the French king decided to continue west to Iconium. The French king may have thought that having defeated the first Seljuk ambush, he could defeat others. A week later the Seljuks struck again.

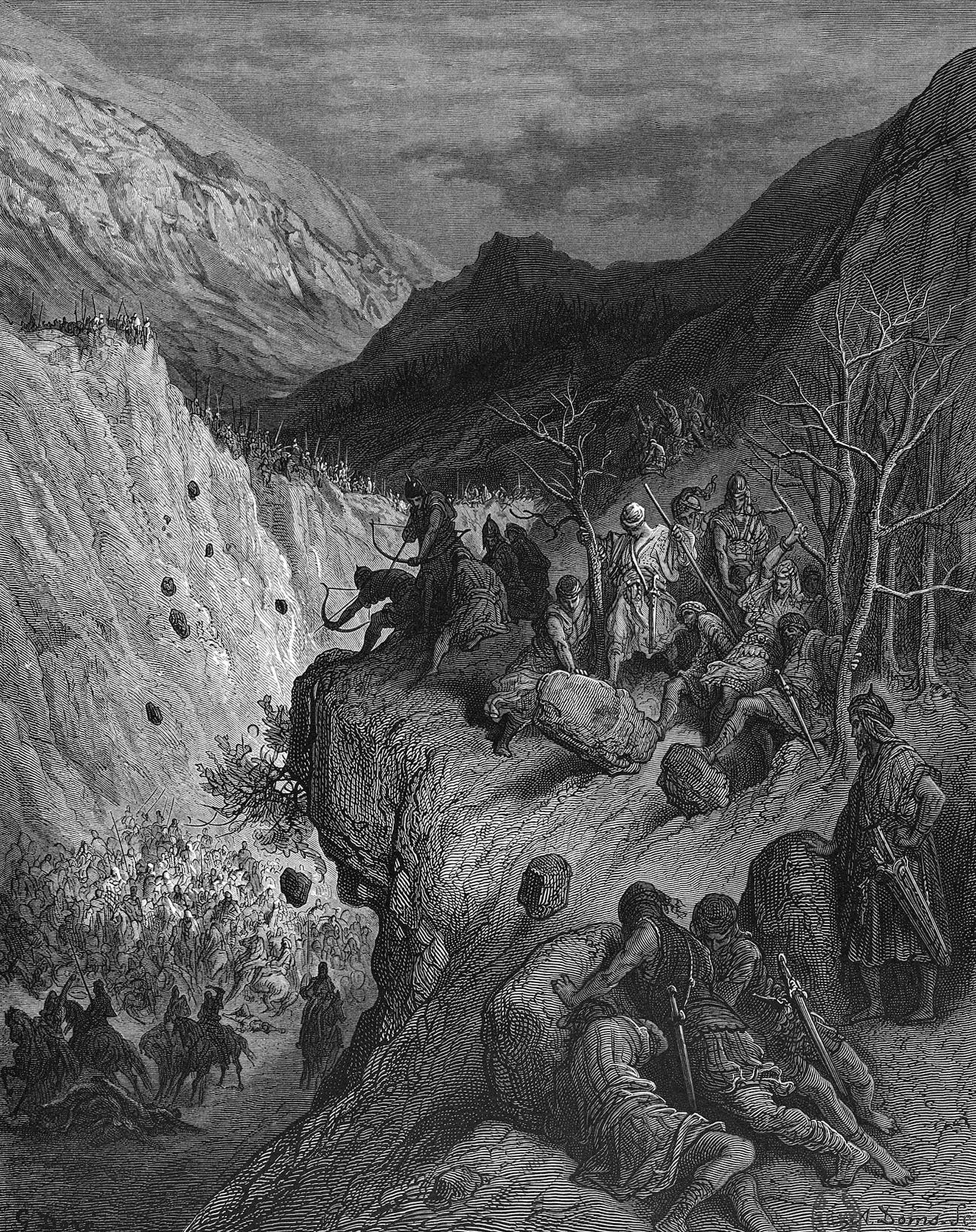

When the French army was making its way through the high pass next to the 8,400-foot peak of Mount Cadmus, the Turks launched a vigorous attack. The vanguard under Lord Geoffrey de Rancon had not stopped at the top of the pass to await the long baggage train, but instead had crossed to the east side to search for a bivouac. While the baggage train wound its way up the mountain, the king had decided to order the rearguard into camp on the west side of the pass. The Seljuks, who were well-acquainted with the network of trails, attacked the supply train. Louis led his retainers in a spirited counterattack to save the baggage train. Many of the Turks dismounted in the rough terrain, and a sharp melee ensued.

The Seljuks gained the upper hand and drove the baggage train and its defenders, including the French king in his royal blue cloak, into a narrow gorge. Louis became unhorsed, either because his horse tumbled or was killed by Turkic arrows. Alone and surrounded, he used tree roots to climb partway up a cliff and assumed a defensive position on a shelf of rock.

“The enemy climbed after, in order to capture him, and the more distant rabble shot arrows at him,” wrote Bishop Odo of Deuil. “His cuirass protected him from the arrows … and he defended the crag with his bloody sword, cutting off the hands and heads of many in the process.”

The Turks fighting him, though, believed him to be a lord or high-ranking knight, but were unaware he was the king. With nightfall fast approaching, they left him to plunder donkeys and mules from the baggage train, which were laden with provisions.

This time, there was no question but that the Turks had won the clash, for the French army suffered heavy losses. Up to that point Louis had entrusted command of the vanguard to various high-ranking French lords whom he rotated through the position so that they could share in the honor and glory, but from that point on the French king gave the Knights Templar in his ranks responsibility for leading the vanguard. They instilled fresh discipline on the mounted troops in the vanguard.

Louis continued east. The Turks launched another devastating surprise attack while the crusader column was strung out crossing the headwaters of the Dalaman River. At that point, Louis knew that his best hope for keeping his army intact was to march due south to Antalya, where he hoped to embark aboard Byzantine ships for the Holy Land. He arrived at Antalya with the survivors of his army in late January. The Greeks only had enough ships to transport the royal guard, other knights, and the best-equipped infantry. The other infantry would have to march along the coast of Anatolia to Antioch. Louis and his knights arrived in Antioch on March 19.

After recuperating from his wounds in Constantinople, Conrad embarked with the remnants of his army and newly hired mercenaries from Constantinople on March 7. A storm scattered the ships, though, and the German contingent arrived at different ports in the Holy Land.

Louis arrived in Antioch in late March, where he was a guest of Prince Raymond of Antioch. Raymond, who before his arrival in the Outremer in 1136 had been the Count of Poitiers, was Eleanor of Aquitaine’s uncle. After the loss of Antioch to the Seljuk Turks in 1084, the Byzantine emperors were keen to recover it. They had pressured the Franks, to whom they had furnished military support, to return it to them. The Franks had been reluctant to relinquish Antioch. Eager to restore imperial control over Antioch, Emperor John II Comnenus had arrived with a Byzantine army before the walls of the great port-city in 1137. Fighting erupted briefly between the Franks and the Greeks, but John eventually called off his attacks and resorted to trying to find a diplomatic solution to the problem. His successor, Emperor Manuel I, succeeded in compelling Raymond to acknowledge the Byzantine emperor as the rightful sovereign of Antioch.

Raymond was keen for King Louis to either help him recover Edessa or help him take Aleppo from Seljuk Atabeg Nur-al-Din. If this could be done, Raymond would likely become the sovereign ruler of the newly acquired towns and territories. Unfortunately, Nur-al-Din had laid waste to Edessa to prevent it from ever becoming a Frankish stronghold again. He had massacred the Armenians in the city and torn down its remaining walls. Louis had a falling out with Raymond, whom he suspected of having an affair with his wife, and had no intention of assisting Raymond in any military endeavor against the Muslims. Louis left Antioch for Jerusalem in late May.

During this time, Conrad met with King Baldwin in Jerusalem in mid-April, and together they agreed that Damascus, and not Edessa, should be the main objective of the crusade. Since Conrad was the leader of the Second Crusade because of his seniority, it was in his power to make this change. Fortunately for both Conrad and Louis, two additional fleets arrived with crusaders in the late spring. One fleet bore men from southern France who had taken the cross. Another fleet brought crusaders from England, Flanders, and north Germany.

The armies that fought the Franks during the crusades included Turks, Arabs, and Kurds. The troops consisted of a core of professional warriors drawn from the fiefs of the Seljuk ruling class, known as the Askar. Anur’s army was rounded out with the urban militia known as the Ahdath, which consisted of younger members of the merchant and artisan classes. Mounted and well-armored, the Askar warriors fought with lance, shield, and sword. The Ahdath troops—recruited from the lower-classes of Damascus—fought on foot with javelin, sword, sling, and bow. Lastly, there was a very large body of Turcoman, Kurdish, and Arab mounted horse archers. In an urban setting, any of the mounted troops could fight just as well dismounted if necessary. Anur had 7,000 troops at the outset of the battle, but over the course of the first few days an additional 8,000 troops arrived. The reinforcements consisted of Syrian foot archers arriving from the Bekaa Valley and Turcoman mercenaries belonging to Sayf al-Din’s Zengid army, who crossed the Nahr Tawra Canal south of Qabun and entered the city through its eastern gates.

Baldwin, Conrad, and Louis, as well as religious officials and their senior lords, gathered at Palmarea near Acre on June 24, 1147, to confirm Damascus as their objective and plot their strategy for capturing the city. Those attending the assembly at Palmarea unanimously agreed to march against Damascus. Baldwin informed Conrad and Louis that he would summon all of the military forces of his kingdom to participate in the expedition. Baldwin’s troops included more of the Knights Templar stationed in the Holy Land. Additionally, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, the archbishops of Caesarea and Nazareth, and the bishops of Banyas, Beirut, Bethlehem, and Sidon participated with their retinues. Last but not least, seven Frankish lords of the kingdom brought their personal troops with them.

When Anur learned shortly afterwards of the crusader plan to attack Damascus, he hurriedly dispatched messengers in late April to the Zengid rulers Nur al-Din and Sayf al-Din Ghazi, requesting reinforcements in anticipation of a major attack by the Franks on his city. The rival Zengi and Burid dynasties set aside whatever animosities they bore for each other in the face of the Frankish offensive.

The newly arrived crusaders and Baldwin’s organic troops totaled 50,000. The great crusader army set out in mid-July with Baldwin leading the vanguard, Louis the center, and Conrad the rearguard. Although the senior Frankish commanders were well aware that the walled fields and orchards of Damascus offered the defenders excellent fighting positions, they nevertheless decided to fight their way through them, reasoning that the irrigated fields would furnish water and food for their horses and men.

The low walls of Damascus in no way rivaled the ancient high walls of Frankish-held cities, such as Acre, Antioch, and Jerusalem, and therefore the crusaders believed that they would easily be able to carry the city by assault without having to undertake a formal siege. Even so, some of the Frankish lords familiar with the defenses of Damascus estimated it might take as long as 15 days to capture the city. The three senior commanders, Conrad, Louis, and Baldwin, all knew that they would not have that much time, because they rightfully predicted that a Zengi army would march to the relief of their fellow Muslims in Damascus. Because they hoped to carry the city by assault, the Frankish leaders of the expedition opted not to bring cumbersome siege equipment with them that would slow their march.

As the crusaders made their way towards the mountain range of Mt. Lebanon west of Damascus, Muslim troops from throughout the Emirate of Damascus assembled in the city. Anur established his headquarters in the citadel adjacent to the north wall of the city. Anur had deployed a combination of Askar and Ahdath troops to cover the main roads leading into the city from the west and south.

In mid-July, the crusader army marched east from Acre to Tiberias. It then marched north through the Jordan Valley and paused for several days at Banyas before crossing the southwestern frontier of the Emirate of Damascus. Once inside enemy territory, the crusaders bivouacked on the night of Friday, July 23, at the village of Kiswa, which was situated on a low ridgeline four miles south of the city.

The following morning, the crusader army marched by the left flank in order to move into position to advance on the city from the west. Heavy fighting soon broke out at Rabwa, a key village in the gorge where the Barada River passed beneath Mount Qasioun on its way into the fertile plain surrounding the city. The Muslim forces at this location had erected a series of barricades across the road, behind which were posted rows of archers. Baldwin’s troops began slowly and steadily driving back the Damascene troops from their positions behind the barricades. They also attacked in force Muslim archers and spearmen in strong positions in the orchards and walled gardens. Muslim archers in wooden towers added their firepower to the defense of the western approach.

When Anur learned that the Franks had committed themselves to an attack from the west, he ordered Turcoman and Arab reserve forces held inside the city to march to the aid of those already engaged on the west side of the city. In addition, Anur ordered the Muslim commander south of the city to shift his troops to support those already engaged to the west.

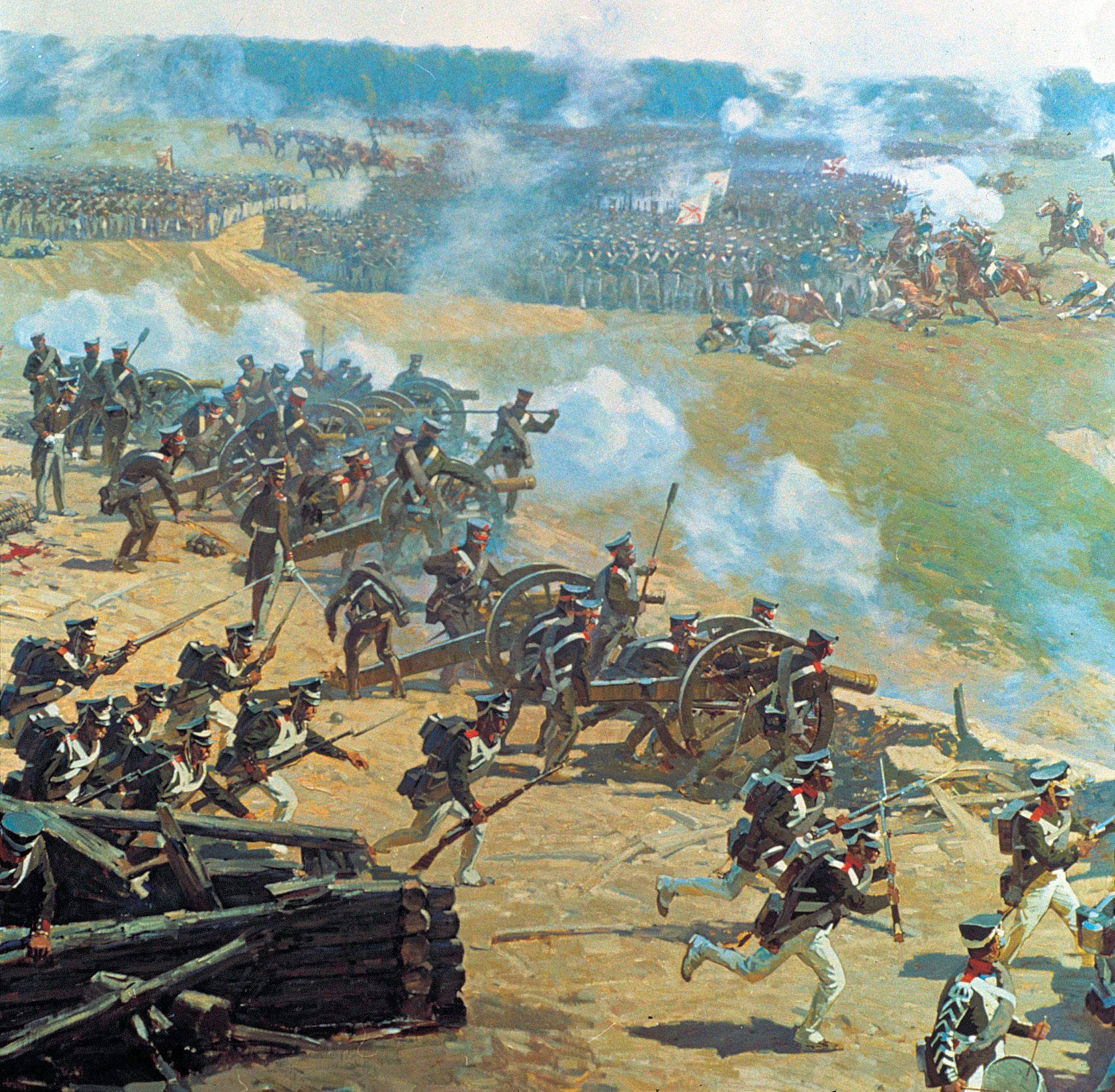

Baldwin’s troops succeeded in smashing through the Muslim commander’s position at Mizzah Jabal by midday. As the Muslims withdrew to establish a new line of defense, the crusader army began to shift from column into several lines of battle. Most of the Frankish knights dismounted to fight on foot since the terrain was not conducive to cavalry operations. Baldwin, reinforced by Louis’ troops, assailed a new Muslim position along the Barada River. Heavy fighting occurred as Muslim reinforcements arrived, and the Muslim commanders tried to hold their position against repeated assaults by the heavily armored and well-equipped crusaders. The Frankish knights and sergeants all wore helmets and mail that repelled the light Arab and Turkish arrows.

The Damascene army succeeded in preventing the first two divisions of crusaders from crossing the river, but the arrival of the Germans at the front lines tipped the battle in favor of the crusaders. Conrad’s mounted knights and sergeants dismounted and waded into battle with their heavy swords. These fresh troops forced a crossing of the river. Once the Franks had gained a secure foothold on the north bank of the Barada River, the Damascene troops fell back towards the city.

Work detachments consisting of pioneers and volunteer from the military units late in the afternoon of Saturday, July 24, began felling trees from the orchards to construct a field fortification to protect their encampment and their main siege position on the west side of the city. Meanwhile, mounted detachments of crusaders began raiding to the north of the city. One group set fire to the mud-brick and wooden houses in the suburb of Faradis just outside the northern gates. To the east, a sizeable force of crusaders moved into a blocking position at Rabwa in an attempt to stem the flow of Muslim reinforcements to the city from the Bekaa Valley. The blocking force remained largely ineffective throughout the battle, though, because the arriving Syrian archers simply bypassed their position by crossing the high ground north of it.

The intensity of the fighting increased substantially on Sunday, July 25, with fresh Muslim troops arriving at Damascus from the northwest and northeast. During the night, the Ahdath had erected fresh barricades in the streets and alleys nearest the west walls in an effort to delay as long as possible any attempt by the crusaders to storm the city. Anur assembled the bulk of his Askar and Ahdath troops in front of the Great Mosque in the center of the city, where Muslim holy men exhorted the troops to fight a jihad and dislodge the Christians from their positions around the city.

While Anur and the holy men rallied the Muslim warriors, the crusaders began shifting all of their forces, except for those at Rabwa, to the south bank of the Barada River. In so doing, the three Christian kings sought to concentrate their resources for a major assault on the west walls of the city. Baldwin instructed his pioneers to mark out a new base camp on the south bank in the expansive tract of grassland known as the Green Maydan, which was where Muslim cavalry trained for battle. The camp was situated about one-and-a-half miles behind the front lines.

As the crusaders forces on the north bank of the river were in the process of withdrawing to the south bank, Anur’s army counterattacked them. The Damascene troops also attacked the crusaders’ siege works, which forced the Franks to switch to the defensive in an effort to hold their forward positions. The Franks fought ferociously, inflicting heavy casualties on the Muslims. Several prominent Muslims were slain in the fighting. Two were revered holy men, and the third was the young cavalry commander Nur al Dawlah Shahanshah. He was the older brother of the future Ayyubid Sultan Saladin, who was just 11 years old at the time of the battle.

The crusaders eventually extracted their forces from the northern bank, which allowed them to reinforce their forward positions. By midday, the Damascene army had succeeded in recovering control of the north bank. The fighting see-sawed back and forth in front of Bab al-Jabiya, one of the city’s seven ancient gates, which was located in the southwestern corner of the city. While the battle raged, work detachments on both sides felled trees and hauled timber to build defensive barricades. Anur knew that the walls of the city could not withstand a sustained assault, and he issued orders to his subordinates to ensure that the Muslims put new obstacles in the approaches to the walls. The barricades were constructed of “huge, tall beams,” wrote William of Tyre, the Jerusalem-born chronicler.

Heavy fighting occurred on Monday, July 26. The number of Muslim reinforcements coming into the city increased substantially. It included not only Arab soldiers from near and far, but also included the vanguard of a relief army sent by Sayf al-Din Ghazi. Rather than going straight into battle, the reinforcements from Mosul entered the city and were directed into battle by local commanders. Having secured the northern bank, Anur’s directed his attacks primarily against the Christian siege positions. The Franks dared not leave the protection of their palisades or become separated from their commands because the enraged local militiamen and villagers picked off patrols and guards. “[They] put to flight all of the sentries, killed them, without fear or danger, taking the heads of the enemy they killed and wanting to touch these trophies,” wrote Abu Shama, a 13th-century Arab historian.

By this time, the battle had swung in favor of the Muslims. Anur ordered the attacks on the crusader field works to continue on Tuesday, July 26. The leaders of the crusader army learned about this time that a large Zengid army had advanced as far south as Homs, Syria, and would soon arrive at Damascus. Sayf al-Din had led his troops on a 400-mile march from Mosul to assist Anur. Marching southwest through Syria, he had joined forces with his brother, Nur al-Din, who had raised an army of Aleppans.

The combined Zengi army reached Homs, which was 100 miles north of Damascus, on July 24 and was estimated to arrive outside the city in five days. Therefore, it was imperative that the Franks force their way into the city before the Zengis; the addition of their troops would greatly swell the Muslim numbers. From a tactical standpoint, they would be able to maneuver to sever the Christians’ supply line. They would also be able to bypass Damascus and advance on either Acre or Jerusalem, which would force the Franks to raise their siege in order to protect the most precious cities they possessed in the Levant.

The senior leaders of the crusade had known even before the campaign that the south walls of Damascus, which were made of sun-baked brick and mud as opposed to stone, were particularly vulnerable to attack. However, they had deliberately chosen to fight their way through the orchards to the west of the city knowing that this dense agriculture area would feed their army. With their attack against the western gates stalled, they contemplated a shift to the south to strike this weak part of the city’s defenses.

King Louis dispatched one of his senior lieutenants, Godfrey de la Roche Vanneau, the Bishop of Langres with the status of a French duke, in the late afternoon of Wednesday, July 27, to conduct a reconnaissance to assess the defenses of the south and southeastern walls. Vanneau reported that the walls were weak. But most importantly, he pointed out that although water could be obtained from one of the canals, there were no orchards or farm fields in that sector with which to feed the army. The senior commanders resolved nevertheless to establish new siege positions to the south since it was clear they could not force their way through to the city from the west.

The following day, July 28, the shift to the east began, but it proved difficult to execute. The Muslims forces continued to assail the army’s left flank, and guerilla troops of the Ahdath had begun to cripple the crusader army with relentless attacks on small Frankish supply units that operated behind the lines to supply the troops at the battlefront.

The army had only reached the suburb of Qayniya, about two miles from their base camp at Green Maydan, when the senior commanders terminated the siege and ordered the troops to begin conducting a fighting withdrawal to the frontier. The crusader army began its retrograde movement on Friday, July 29, and that day Muslim forces took possession of the Green Maydan and the abandoned crusader siege works beneath the west walls. Mounted Turcoman troops maintained steady pressure on the crusader army for the next 48 hours as it marched back to the frontier.

The dejected crusaders returned to Jerusalem following the reverse they suffered at Damascus. The shame at the defeat was so great that the leaders fell to bickering among themselves. Conrad leveled charges that could not be proved against the barons of the Kingdom of Jerusalem that they had accepted bribes from the Damascenes to redirect the crusader attack from the west walls to the south walls. Contemporary Latin chronicles repeated this allegation and expanded upon it. Deflecting blame was a literary tactic of the chronicles to cover for the military failures of crusader commanders, particularly those of the nobility.

Over the course of the next 10 months, the Seljuks carved up what remained of the Latin County of Edessa. Nur-al-Din and Sultan Masud of Rum each acquired towns west of the Euphrates that had been under Frankish rule.

The two visiting Latin kings from Western Europe did not return home immediately. Conrad tried to rally the crusaders for a fresh attack against the Fatimid Egyptian port of Ascalon, which was 50 miles southeast of Jerusalem. The deep-water anchorage at Ascalon could accommodate a large fleet, and the Egyptian fleet stationed at that location posed a concrete threat to the Genoan, Pisan, and Venetian merchant ships that supplied the Frankish residents of the Levant. Given that the three leaders of the crusade argued as to who was to blame for the debacle at Damascus, Louis and Baldwin were not keen for a similar expedition against Ascalon. Conrad mustered his German troops at Jaffa on the Levantine coast, where he waited for Louis and Baldwin to join him, but they lacked the will for another siege. Therefore, no attack was made on Ascalon.

Conrad departed for home first. He left in September 1148 and arrived in Germany the following spring. Louis remained in the Holy Land, where he traveled extensively but refrained from joining any local offensives. Louis and Queen Eleanor departed in a Sicilian vessel on April 1149 and arrived in France in November.

The upshot of the Second Crusade was that the Sunni Muslim Turkic states to the north and east of the Franks were expanding and their power was increasing, while the Frankish states on the whole were waning in power. This manifested itself in the rise of Sultan Saladin’s Ayyubid state, which controlled not only Egypt but Syria. Following Saladin’s decisive victory over King Guy of Jerusalem at Hattin in 1187, the sultan captured Jerusalem. The three-year-long Third Crusade that began in 1189 had as its objective the retaking of Jerusalem, but the crusaders of that expedition also were unable to fulfill their difficult mission, and Jerusalem remained in Muslim hands.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments