By William E. Welsh

As the sun rose on May 8, 1967, it illuminated the 525-foot-high hill known as Con Thien where the Marine Corps had established a firebase two miles south of the Demilitarized Zone in South Vietnam. Recognized as a critical defensive position in the First Indochina War, the French had built a fort atop the highest of the small mountain’s three knolls. The Leathernecks stationed at Con Thien used the outpost both as an artillery firebase and an observation post.

Con Thien, which in Vietnamese means “small mountain of heavenly beings” was translated by the Americans into “Hill of Angels.” The hill actually comprised three knolls in close proximity to each other. Two of the knolls were side by side and the third was situated south of the left hill.

The Americans, as the French did before them, found the hill to be a superb observation post offering a magnificent, panoramic view of the lush lowlands that were traditionally planted with coffee, pineapple, and bananas.

Standing on the red dirt of Con Thien’s bulldozed plateau, a Marine could look north out over the sand-bagged bunkers, trenches, and barbed wire-laced perimeter, beyond the DMZ into North Vietnam; looking west, he could see the rolling hill country and mountains that led toward Laos; to the east he could see not only the Gio Linh outpost six miles away, but on a clear day even the U.S. Navy warships on the South China Sea.

The heavy fighting begun the previous year along the DMZ had driven out the Vietnamese peasants—the ground around Con Thien was a wasteland, pockmarked with thousands of craters from the shells and rockets fired daily by Communist forces at the imperturbable Marines, although the red soil still boasted dense vegetation in places.

Following the arrival of the first contingent of U.S. Marines at Da Nang Air Base on March 8, 1965, the Marines began carving out safe zones for their forces in I Corps, the northernmost of four tactical zones in South Vietnam established by the U.S. military joint-service command known as Military Assistance Command Vietnam.

Major General Lewis J. Fields’ 1st Marine Division arrived in South Vietnam in early 1966 joining the 3rd Marine Division already in-country. As the war progressed, the 1st Marine Division in the southern part of I Corps fought a mostly counter-insurgency war against Viet Cong forces, while the 3rd Marine Division in northern I Corps engaged the communist Peoples’ Army of Vietnam forces in continuous fighting similar to that of a conventional war. By the end of 1966, Maj. Gen. Lewis Walt’s III Marine Amphibious Force would number 70,000 Marines.

Most of the population of South Vietnam lived in the lush coastal plain along the South China Sea where they grew rice in the fertile river valleys. During their first year in South Vietnam, Marine Corps forces commanded by Maj. Gen. Lewis Walt, who commanded both the 3rd Marine Division and the III Marine Amphibious Force, focused on pacifying the villages of I Corps’ lowlands and cleansing them as much as possible of Viet Cong and military forces. Walt’s 3rd Marine Division comprised the 3rd, 4th, and 9th Marine regiments.

When Walt received a promotion to lieutenant general in March 1966, he continued to command the III Marine Amphibious Force, but command of the 3rd Marine Division went to Maj. Gen. Wood Kyle. Walt continued to direct Marine strategy in I Corps in his role as III MAF commander and as the senior U.S. advisor to I Corps.

A heated policy dispute erupted in mid-1966 when General William Westmoreland, the commander of Saigon-based MACV, pressured the highest echelons of the Navy and Marine Corps to switch their focus from pacification to engagement of North Vietnamese forces infiltrating across the DMZ into Quang Tri Province, the northernmost of the five provinces in South Vietnam’s I Corps.

Westmoreland’s reason for wanting the Marines to aggressively defend the ground south of the DMZ was that he did not want to abandon large swaths of the South Vietnamese interior to the North Vietnamese. Moreover, he wanted to wipeout North Vietnam’s People’s Army of Vietnam forces with search and destroy missions.

Walt vehemently objected to a switch from pacification to the search-and-destroy strategy advocated by Westmoreland. He argued against having Marine units in static positions south of the DMZ because it ran contrary to mobile warfare doctrines. Westmoreland prevailed in the clash with Walt over military strategy when Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington pressured Admiral U.S. Grant Sharp, Walt’s commanding officer, into ordering Walt to comply with Westmoreland.

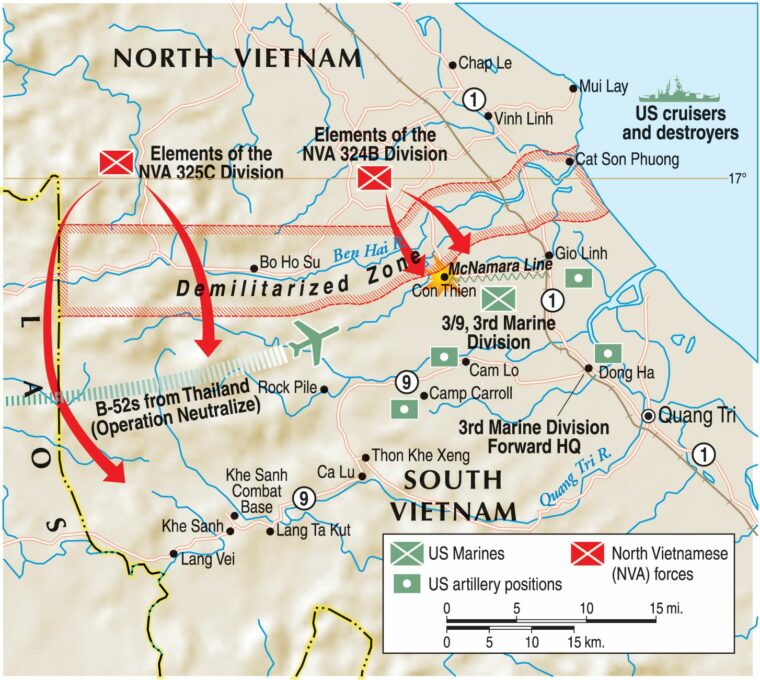

McNamara signed off on Westmoreland’s strategy to defend the DMZ, which called for the Marines to establish a forward supply base at Dong Ha and six fortified outposts south of the DMZ at Con Thien, Gio Linh, Cam Lo, Camp Carroll, the Rockpile, and Khe Sanh. Walt shifted the 3rd Marine Division’s headquarters 50 miles north from Da Nang to Phu Bai so that it might better focus on defending the ground south of the DMZ.

McNamara had also developed a plan for installing a defensive barrier south of the DMZ to assist Marine Corps forces against North Vietnamese incursions into eastern Quang Tri Province. McNamara’s “Strong Point Obstacle System” would consist of a belt of land cleared of vegetation that would be sown with mines and electronic warning devices. The first phase of the project involved the construction of the barrier between the forward outposts of Con Thien and Gio Linh.

Westmoreland had received reliable intelligence in April 1966 that elements of the 8,000-strong North Vietnamese 324B Division were operating south of the DMZ. He instructed Walt to begin conducting regular reconnaissance patrols to determine the location and extent of the infiltration. The patrols began on June 20.

Colonel Donald W. Sherman, the commander of the 4th Marine Regiment, tasked Major Dwain A. Colby with directing Task Unit Charlie, which consisted of two reconnaissance platoons, Company E from the 2nd Battalion of the 1st Marine Regiment, and an artillery battery. The task unit deployed to the large forward base at Dong Ha and the outpost at Cam Lo. Task Unit Charlie quickly confirmed the MACV intelligence that the 324B Division was operating south of the DMZ.

Of the 18 reconnaissance patrols it sent out in a two-week period in July to look for PAVN units, 14 had to be extracted early because of enemy contact. “No patrol was able to stay in the field for more than a few hours, many for only a few minutes,” Colby said.

Having verified the presence of large enemy forces, the 3rd Marine Division kicked off a series of major offensive operations in the second half of 1966 against the 324B Division. The first of these was Operation Hastings that began on July 15 and lasted nearly three weeks. Six Marine and five ARVN infantry battalions engaged in a series of savage skirmishes with elements of the 324B Division, inflicting 700 casualties on the North Vietnamese.

Three Marine Battalions remained in place after Hastings, and soon found themselves under fresh attack by the 324B Division. Because of this, the Marines launched Operation Prairie on August 3. Unlike Hastings, Prairie was designed to be a long-term, continuing operation. The first phase began on August 3, 1966, and the fourth and last phase ended on May 17, 1967.

The situation along the DMZ seemed to be rapidly intensifying—Westmoreland informed Walt and Kyle that U.S. intelligence indicated the PAVN 304th and 341st divisions had moved into supporting positions just north of the DMZ to assist the 324B Division. Marine F-4 Phantom and A-4 Skyhawk fighter-bombers flew sorties against suspected enemy positions from Da Nang Air Base, and Air Force B-52s Stratofortresses based in Thailand and Guam conducted Arc Light missions along the DMZ.

Marine reconnaissance efforts called for using a UH-1E Huey helicopter to insert four- or five-man reconnaissance teams along a suspected route by which the enemy advanced south from the DMZ into northern Quang Tri Province. If the team ran into trouble, Marine infantry battalions at Cam Lo and Dong Ha stood poised to respond immediately. Just like the 1st Cavalry Division, the Marines conducted heliborne assaults to engage the North Vietnamese forces before they could escape.

The fighting along the DMZ between the well-trained and highly disciplined Marines and the dedicated and determined North Vietnamese infantry throughout the second half of 1966 consisted of small unit engagements. In every one of these instances, the Leathernecks hurled back the communist troops. The North Vietnamese, though, retreated north only to replace their losses, regroup, and advanced again using the terrain to their advantage. Marine units sweeping the area south of the DMZ found sprawling underground complexes replete with bunkers, medical stations, and tactical command centers.

General Vo Nguyen Giap, the North Vietnamese minister of defense and commander-in-chief of its military forces, ordered the generals commanding the PAVN divisions to put heavy pressure on Marine Corps outposts that stretched from Khe Sanh in the highlands to the area known as Leatherneck Square, a quadrilateral connecting Con Thien, Gio Linh, Cam Lo, and Dong Ha in the south. Regarding the outpost at Con Thien, Giap told his generals to neutralize the ARVN and U.S. Special Forces garrisoning it.

Giap viewed the buildup of U.S. Marine Corps forces as a promising development. As part of his grand strategy, he was keen to draw the Americans away from the heavily populated coastal areas of South Vietnam so that he could engage them in a grinding war that would produce high casualties and fuel the anti-war sentiment in the United States. The Marines had to defend more than 230 square miles of hills, forested jungle, and verdant lowlands just below the DMZ. They garrisoned scattered outposts that were vulnerable to both constant guerilla attacks and occasional main force assaults.

Most of the fighting took place north of Route 9, which ran west for from Dong Ha on the coast to Khe Sanh near the Laotian border. Westmoreland sent the 3rd Marine Division a battalion (12 guns) of the U.S. Army’s M107 self-propelled 175mm guns to augment the Marines’ organic 155mm and 105mm howitzers. The monster howitzers could hurl a 47-pound shell up to 20 miles and pummel North Vietnamese forces moving through the DMZ. Giap saw the 175mm guns as a particular threat to his forces and ordered the generals of the divisions deployed along the DMZ to take out the guns by any means necessary.

The Marines made good use of their F-4 Phantom and A4-4 Skyhawk fighter-bombers, which flew regular missions against North Vietnamese ground forces. In addition, the Navy sent carrier-based aircraft to pound enemy positions, as well. Navy cruisers and destroyers could also fire on targets near the coast.

The North Vietnamese had their own impressive arsenal of artillery and rocket batteries that included Soviet-designed 85mm, 100mm, 122mm, and 130mm guns, 120mm mortars, and 122mm Katyusha rockets. They had acquired the large Soviet artillery and rockets by early 1966 and Chinese Communist 107mm and 140mm rocket systems by late 1966. The rocket systems, which were lighter and more mobile than the heavy artillery, proved more effective for striking large targets than artillery.

Walt and his Marine Corps generals had 35,000 troops defending the ground south of the 47-mile-long DMZ by late spring 1967. The North Vietnamese Army’s three divisions on the DMZ totaled at least 24,000 troops. The composition of the garrison forces at Con Thien changed substantially at that time as work began on McNamara’s Strong Point Obstacle System. Up to that point, the garrison at Con Thien had consisted of ARVN troops and a handful of U.S. Army Special Forces commanding a group of Civilian Irregular Defense Force troops.

The CIDG troops were Nung tribesmen. The ARVN and Nung distrusted each other, and therefore did not fight effectively together. The composition of the garrison began to change when Company C of the 11th Engineer Battalion arrived in April to begin construction of McNamara’s defensive barrier. They set to work using bulldozers to clear a 14-mile strip that was 218 yards wide. Once they had cleared the vegetation, work would begin on sowing the cleared ground with mines and installing electronic equipment to detect the movement of enemy troops through the zone.

The Marines—from the most senior general down to the lowest rank grunt—scoffed at the efficacy of such a zone. Even worse, the barrier was ineffective at stopping the North Vietnamese, who did not allow it to slow their infiltration. “It was nothing to us,” Le Van Cho, a North Vietnamese soldier, said in a post-war interview. “Every night we would go across it.”

The 3rd Marine Division received its third commander in three years when Maj. Gen. Bruno Hochmuth replaced Kyle on March 18, 1967. Hochmuth would meet a tragic end eight months later when a UH-1E transporting him on an inspection tour of outposts exploded in mid-air and crashed upside down in a rice paddy killing all six onboard.

The Marine engineers cleared the vegetation in the trace between Con Thien and Gio Linh in just two weeks in April, 1967, despite daily shelling from North Vietnamese artillery and mortars. After finishing that job on May 1, the engineers began clearing a 550-yard-wide strip around the Con Thien outpost. They intended to replace the outposts’ makeshift and haphazard perimeter defenses, in which the standard barbed wire defenses were augmented by hand-grenade booby traps and trip wires, with a more sophisticated system consisting of concertina wire, anti-tank mines, and anti-personnel explosive devices. In addition, the engineers planned to construct new bunkers that could withstand direct hits by North Vietnamese heavy artillery.

North Vietnamese soldiers fought with weapons supplied by communist China and Russia. They went into battle armed with the Soviet 7.62mm AK-47 assault rifle. For suppressive fire, infantry units used the Soviet-designed 7.62mm RPD light machine gun, the Soviet wheel-mounted DShK 12.7mm heavy machine gun, and the Chinese Type 56 light machine gun.

To take on American tanks, halftracks, and other vehicles, they used the shoulder-fired RPG-2 40mm anti-tank grenade launcher and the RPG-7 rocket-propelled grenade launcher that fired a 40mm high-explosive, anti-tank missile that could penetrate nine inches of armor.

The Marines had a healthy respect for the North Vietnamese soldiers with which they went toe-to-toe south of the DMZ. “The NVA had great fire discipline and good marksmanship skills,” Westmoreland wrote in his memoirs. “They built excellent fortifications and incredibly impressive trenches and emplacements.”

The Marines revived their counteroffensives against the North Vietnamese with the six-week-long Prairie II that kicked off on February 1, the four-week-long Prairie III that began on March 19, and the three-week-long Prairie IV began on April 20. The operations began with the usual patrols and sweeps designed to find and destroy the North Vietnamese operating south of the DMZ.

Elements of Lieutenant Colonel Theodore J. Willis’ 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, arrived in early April to furnish security for the engineers building the trace between Con Thien and Gio Linh. Elements of the Marine 3rd Tank Battalion and a platoon of U.S. Army M-42 Dusters also arrived to furnish crucial firepower in case of a North Vietnamese ground attack. While the engineers toiled on their construction project, enemy snipers fired on them and mortar crews lobbed rounds. The engineers had completed half their work when Operation Prairie III ended on April 19 with the North Vietnamese suffering 252 killed and the Marines losing 56. Operation Prairie IV began the following day.

The North Vietnamese had shown in previous operations that they could maneuver largely undetected around Con Thien. But they suffered from flawed intelligence regarding ARVN and Marine positions.

Unknown to the North Vietnamese, two reinforced battalions, companies A and D, of Lt. Col. Theodore J . Willis’ 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, had replaced the ARVN troops stationed at Con Thien in April 1967 when construction began on the trace between Con Thien and Gio Linh. A few U.S. Special Forces remained on the outpost to command the Nung mercenaries, who also remained stationed at the outpost. The Nung irregulars lacked the training to stand up in battle to the North Vietnamese, though. In addition, three M48A3 Patton tanks of Alpha Company, 3rd Tank Battalion, were stationed at intervals along the north side of Con Thien’s perimeter.

The senior command of two battalions of North Vietnamese massing to the north of Con Thien in late April mistakenly assumed that only ARVN and Green Beret-led Nungs defended the outpost.

Since the engineers were still hard at work during the daytime clearing trees and brush from a 550-yard-wide strip the around the perimeter at Con Thien, North Vietnamese snipers and mortar teams lurked nearby to harrass them. What is more, occasionally a North Vietnamese artillery shell or rocket exploded in their midst. Anyone of those threats could produce one or more casualties and send a corpsmen and litter bearerz s to whisk the injured grunts to the battalion aid station inside the perimeter. But as everyone headed for their respective bunkers the evening of May 8 they could breathe a collective sigh of relief for on the whole the night was a lot safer than the day at Con Thien.

The hill’s two knolls in the northern half of the outpost were situated side by side. The western one was observation post #1 and the eastern one was observation post #2. Observation post #3 was situated directly behind observation post #1 on the third knoll.

Company D defended the northern half of the perimeter, Company A defended most of the southern half, and the Green Berets and Nungs defended the southeastern corner of the outpost. Although the Green Beret and Nungs should have been tied tightly into the right flank of Company D and the left flank of Company A, the Marines had cordoned them off with concertina wire because they did not trust the Nungs.

After sunset, a battalion of North Vietnamese moved into position for an assault from the northeast to strike Company D’s section of the Con Thien perimeter, and another battalion took up positions to the southeast opposite where the Green Beret and Nungs were positioned on the perimeter. The forces consisted of the 4th and 6th battalions of the 812th North Vietnamese Regiment of the 324B division.

The standard NVA battalion had a headquarters platoon of approximately 20 men and three 60-man companies. Two groups of sapper penetration teams would lead the attack and establish gaps in the perimeter not only for sapper assault troops, but also for the North Vietnamese main force. The sappers entrusted with penetration of the perimeter carried Bangalore torpedoes, wire cutters, and AK-47s. The sapper assault teams were armed with AK-47s, RPG-2’s firing anti-tank grenades, and RPG-7s firing shaped charges.

For the next few hours, North Vietnamese officers reviewed the plan of attack with their troops for one last time. Although sapper commandos routinely carried satchel charges to take out U.S. heavy weapons positions, many of the follow-on troops also carried satchel charges with instructions to destroy the Marine engineers’ construction equipment and to help them destroy bunkers both in the heart of the compound and along the trench line.

The North Vietnamese timed their attack on the outpost at Con Thien to coincide with the 13th anniversary of the French surrender at Dien Bien Phu. At 2:55 a.m. a North Vietnamese soldier fired a green flare that lit the sky on the southeast side of the Con Thien perimeter signaling the commencement of a furious 300-round bombardment by mortars and artillery that lasted for 15 minutes. The artillery rounds came screeching in with a roar. The shells slammed into the hilltops, slopes, and level ground of the outpost. The Marines learned after the assault by interrogating captured North Vietnamese prisoners that the NVA mortar teams had painstakingly registered their mortars on positions inside Con Thien for many weeks. To pin down U.S. relief forces at nearby outposts, the NVA simultaneously shelled Gio Linh, Camp Carroll, and Dong Ha.

While the rockets and shells slammed into the outpost, highly trained NVA sapper commandos rushed forward with bamboo Bangalore torpedoes to blow gaps in the perimeter defenses. They succeeded in some sections of the northern perimeter, marking the gaps they created in the northern perimeter defenses where Company D was situated with small, pennant-shaped red flags for the troops following them. Next came NVA sappers with satchel charges. Meanwhile, the NVA outside of the perimeter laid down a strong covering fire to assist the sappers.

The main force of the North Vietnamese rose up and raced towards the outpost en masse at 4 a.m. Armed with AK-47s, RPGs, and several flamethrowers, the communist soldiers poured through the gaps on the north side of the outpost and the southeast side. Although the main attack was directed at Captain John F. Juul’s Company D on the northern section of the perimeter, another attack targeted the section of the perimeter defended by the Nung irregulars.

Those bearing the satchel charges hurled them at the trench-line bunkers. They blew up a number of these bunkers, and the explosion left the defensive positions a jumble of collapsed beams and torn sandbags. They also sought to take out the bulldozers, 81 mm mortar positions, and the command bunkers.

North Vietnamese sappers and soldiers armed with satchel charges crept in low crouches and crawling forward on their stomachs to hurl one-quarter-pound blocks of TNT into the trenches where the Marines were hunkered down. These TNT explosions equaled mortar blasts and produced many of the casualties that the Americans suffered in the night attack. Meanwhile, the three flamethrower teams, which had come through the gaps in the wire with the main assault force, sprayed fire into several of the bunkers—a number of Marines huddled inside were suffocated and burned to death by the flaming fuel.

Captain Juul, the commander of Company D, went down early in the assault with bullet wounds to both legs. He continued firing his .45 caliber pistol at the enemy and speaking into his radio handset. “Stay put in your trenches,” shouted Sergeant Mailon Hall of Company D to the nearby Marines. He did not want the Marines becoming mixed up with the enemy and killed by friendly fire. “We are going to kill anything that moves.” Despite being badly wounded, Juul requested reports on the extent of enemy penetration from elements of his company. After making an assessment of the situation, Juul had two Marines hold him in a standing position while he skillfully coordinated a counterattack on the North Vietnamese force. He later received the Silver Star for his valor.

Marines wielding faulty M-16s had to discard many of their weapons because they jammed. They did not have time, in the heat of battle when every second counted, to assemble their cleaning rods in order to clear a jammed shell casing out of their rifles. The engineers, who were armed with reliable M-14s that did not jam, charged over to Company D and helped plug the gaps in the north side of the perimeter. The engineers poured a steady fire into the attacking NVA and played a significant role in helping slow the enemy’s advance.

The defenses of the CIDG section on the southeastern corner of the perimeter collapsed completely. NVA forces poured into the CIDG area. Green Beret Captain Craig Chamberlain and two Green Beret sergeants of Detachment A-110, 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), 1st Special Forces, who were in a separate command bunker in the Nung section of the outpost, fought off repeated assaults. An NVA flamethrower operator stuck the nozzle of his weapon spraying jellied liquid in one of the bunker’s aperture, but the Green Beret soldiers survived the ordeal because the fuel did not fully ignite inside the bunker. At that point, the three Green Beret withdrew to a Navy Seabee position where they continued engaging the enemy.

When the assault began, the NVA fired a rocket-propelled grenade at the center tank that penetrated the turret and exploded severely injuring the crew inside. Despite his wounds, Sergeant David Danner, the tank platoon’s mechanic who was in the gunner’s seat, helped the other members of his tank crew out of the tank and to the medical bunker. Danner had fragment wounds to his back and arms and was badly burned as well.

Corporal Charles D. Thatcher, the commander of the right tank on the northeastern side of the perimeter, was asleep under his tank in order to protect himself from possible random enemy artillery shelling that occasionally occurred at night. In the first few minutes of the attack, he stayed in his position to avoid being shot by the sappers.

But Lance Corporal David Gehrman, who was a member of Thatcher’s crew, climbed into the tank and opened fire with its .30 caliber machine gun. An NVA high-explosive, anti-tank round penetrated the turret filling it with smoke. Gehrman yelled for the men to evacuate the tank. The other two crew members in the tank, though, had received wounds that would prove fatal. A second blast struck the tank sending Gehrman flying through the air. Gehrman struck the ground, and when he rose up, an enemy soldier fired at him striking his leg. While dragging himself to a trench, Gehrman was shot in the other leg. Two Marines saved his life by dragging him into their bunker.

Thatcher, who had been beneath the tank, was wounded in the neck and back by shrapnel from the rocket-propelled explosives that struck the tank. Despite his wounds, he climbed into the tank and fired the remaining .30 caliber ammunition. Upon exiting the smoldering wreck of the tank, he snatched up a Marine rifle from the ground and killed an enemy RPG team preparing to fire on the left tank in the northwestern corner of the perimeter.

Meanwhile, Sergeant Danner returned to the center tank, grabbed the .30 caliber machine gun and ammunition boxes. He set up the machine gun on open ground and began spraying the attacking North Vietnamese with it in an attempt to prevent them from reaching the main command bunker. Both Thatcher and Danner later received the Navy Cross acknowledging their valor.

Gunnery Sergeant Barnett Person, the commander of the left tank in the northwestern section of the perimeter, gathered his crew, started up his tank, battened down the hatches, and began rumbling into action against the NVA inside the perimeter before the North Vietnamese could target his tank. The 52-ton steel monster rumbled around the perimeter firing at the North Vietnamese with its 90mm cannon, as well as its coaxially mounted .30 caliber machine gun. The situation called for anti-personnel rounds, rather than high-explosive rounds, and Person directed his loader to use canister and beehive rounds. The latter contained scores of deadly metal darts known as flechettes.

North Vietnamese soldiers tried several times to knock out Person’s tank by climbing atop it in order to hurl a grenade or satchel charge into the turret through the commander’s copula, but they were unsuccessful given that Person had secured the hatch. Person’s tank enabled the Marines of Delta Company to halt further penetration of their section of the perimeter.

The men of Alpha Company were crouching in their fighting holes and trenches when the two NVA battalions attacked. The commander of Alpha Company dispatched his 1st platoon to reinforce the hard-pressed Marines of Delta Company, while keeping his 2nd and 3rd platoons manning the southern perimeter. The 1st Platoon also was tasked with helping protect an ammunition resupply convoy coming from a nearby base.

The Marines of Delta Company who survived the initial attack fought back fiercely against the North Vietnamese troops inside the wire. With reinforcements from Company A, the engineers, and the tank crewmen, they were holding their own, but many of their M-16s had also jammed and been discarded, and they, too, were running low on ammunition.

An hour after the main force attacked, the North Vietnamese inside the perimeter had passed between observation points one and two, which were on the northwestern and northeastern knolls, respectively, and were heading towards a landing strip on the south side of the outpost and the medical aid station. The 1st platoon of Company A ran headlong into the enemy troops and engaged them. At that time the Marines south of Observation Point #2 manning the 81mm mortars ran out of illumination rounds, but fortunately a flare plane arrived on station with enough flares to light up the outpost until daylight.

An ammunition resupply convoy comprising an Army M42 Duster, two tracked howitzers (known as Landing Vehicle Tracked Howitzer, or LVTH), and two ¼-ton utility trucks (like a jeep) dispatched from a nearby location at the start of the battle was approaching Con Thien when an NVA soldier fired an anti-tank rocket that set the Duster afire. A North Vietnamese sapper then hurled a satchel charge at the second vehicle in line, which exploded under it setting it afire, as well. The crew of the LVTH survived the explosion and jumped out of their vehicle. The second LVTH became entangled in concertina wire. The trucks, though, with covering fire from the platoon from Alpha Company, succeeded in getting inside the perimeter.

Delta Company completely sealed off the northern perimeter just before daylight. The fight had lasted two hours, from 4 a.m. to 6 a.m. At daylight, the main force of the NVA outside the perimeter withdrew. For the next several hours the Marines mopped up inside the perimeter. They had succeeded in killing or capturing those inside the perimeter by 9 a.m.

Because the Marine engineers and Seabees had completed clearing brush around Con Thien’s perimeter, the Marines were able to deny close cover to the attacking communist force and easily target them in the open as they advanced and retreated. The three M48 Patton tanks, as well as the two LVTHs, both fired beehive anti-personnel rounds. The M48 Patton tanks used APERS-T beehive rounds for their 90mm main gun.

The Marines lost 44 killed and 110 wounded for a total of 154 casualties. The NVA lost 197 killed and eight captured for a total of 205 casualties. The retreating NVA force took with it an unknown number of wounded communist soldiers. A conservative estimate is that they likely carried off as many as 200 wounded. In addition, another 200 North Vietnamese were probably killed by U.S. airstrikes and artillery fire as they retreated north.

The Marines recovered 72 abandoned weapons, including 19 RPGs, three light machine guns, and three flamethrowers. The firefight marked the first time that the NVA had used flamethrowers against the Marines.

During and after the assault, NVA casualty teams transported the wounded to an underground field hospital 2,000 yards north of Con Thien. An NVA command post also was located underground in the same general area.

The Marines learned afterwards that the NVA had mistakenly believed that ARVN and CIDG troops defended Con Thien. They did not know that Marines had arrived to defend the outpost. Moreover, the NVA showed an inability to modify their tactical plans in the middle of a firefight. They had attacked the strongest part of the perimeter, and they had continued to press their attack on that sector even when it became apparent they were suffering heavier resistance than they had expected.

In late May 1967 the Marines and ARVN forces undertook a series of coordinated joint operation into the southern half of the DMZ to clear out North Vietnamese staging areas for attacks against Leatherneck Square, but this proved to be only a fleeting reprieve.

The North Vietnamese tested the Marine defenses at Con Thien again two months later. After the North Vietnamese 325C Division lost a struggle for the strategic hills north of Khe Sanh, the North Vietnamese leadership decided to reinvade eastern Quang Tri Province. For a two-week period in the first half of July, the North Vietnamese again launched attacks in eastern Quang Tri Province. The Marines defending Con Thien suffered heavy losses, but hurled back the communists with a combination of air and artillery strikes. The Marines then launched another counterattack. This one, known as Operation Buffalo, inflicted 1,290 killed in action on the North Vietnamese 90th Regiment at the cost of 160 Marine lives.

The fighting around Con Thien resumed anew on September 11. In an attempt to conquer Quang Tri Province, the North Vietnamese launched their heaviest bombardments of Con Thien in the war. For the next seven weeks, the fighting see-sawed back and forth, but the North Vietnamese broke off their attacks at the end of October having lost another 2,000 soldiers.

Although the North Vietnamese Army had suffered heavy losses in the fighting around Con Thien, Giap had succeeded in drawing the Marine Corps units away from the population centers on the coast in preparation for the coordinated series of offensives throughout South Vietnam that would be known as the Tet Offensive of 1968. Giap’s plan, which would work, was to show that despite a huge military commitment to South Vietnam, the U.S. military was not winning the war in South Vietnam. Although the U.S.-ARVN forces would win the tactical battle, Giap would win the all-important propaganda war that pushed the Americans towards a gradual withdrawal during the Nixon administration.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments