By Chuck Lyons

On the morning of September 11, 1777, 19-year-old Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette, calmly sat on his horse next to George Washington, commander in chief of America’s revolutionary forces. The two men could see the dust as parts of a 15,000-man force under Viscount General William Howe, commander of British forces in North America, formed in the distance across Brandywine Creek and a small American force moved into position on the other side of the water. Lafayette and Washington were on the high ground north of the creek west and a little south of Philadelphia.

The youthful Lafayette had never been in combat. The previous December, he had met in Paris with American agent Silas Deane and volunteered to fight with the American rebels. Lafayette had recently become a Freemason and talk of the rebellion with descriptions of a brave American people fighting for liberty had fired his youthful idealism. “My heart is dedicated [to the Americans],” he said at the time.

Negotiations between American agents and French officials had been continuing since early in the conflict. The Americans sought French supplies, manpower, and naval support. As for the French, they hoped that by aiding the Americans they could restore French influence in North America and revenge their loss to Great Britain in the French and Indian War. The French already were secretly aiding the Americans by supplying large quantities of gunpowder, but they were uncertain as to the strength of American arms and of the Patriots’ ability to defeat the British. That uncertainty held them from further yanking the tail of the British lion with any official and public alliance with the Americans.

Lafayette had set sail for the newly formed United States in April 1777 and arrived in South Carolina on June 13. He travelled to Philadelphia, the Patriot capital, and presented himself to the overburdened Continental Congress, which was beset by foreign officers demanding high position, many of whom could barely speak English. Lafayette used his Masonic membership, as well as his charm and willingness to serve without pay, to gain access to the leaders of the rebellion. The members of the Continental Congress named Lafayette a major general without command on July 31, 1777, and he rode to join Washington.

The two men met at a dinner in August. Washington, who was as charmed by the young Frenchman as the Congress had been, gave the young Frenchman a position on his staff. The British subsequently landed south of Washington’s force in late August, and after a sharp clash on September 3 at Cooch’s Bridge in Delaware, hard marched toward Philadelphia. Washington responded by abandoning his position on Red Clay Creek near Newport, Delaware, and deployed his men along the Brandywine at Chadds Ford, which lay astride the most direct route to Philadelphia.

Shortly after the American Revolution began at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, in April 1775, Washington appeared at the Second Continental Congress in a military uniform. He had prestige, military experience and bearing, and a reputation as a steadfast patriot. The members of the Continental Congress realized that Virginia, the largest of the 13 American colonies and Washington’s home, deserved a leadership role in the revolution and that the New England colonies needed to ensure the support of the southern colonies. For those reasons, in June they appointed him to serve as commander in chief of American forces.

Future U.S. President and Continental Congress delegate John Adams praised Washington’s “great experience in military matters.” He would be of much service to the cause, Adams said.

Since then Washington had managed in early 1776 to force the British to evacuate Boston. Following the loss of New York City to Howe in the late summer of the same year, Washington had led his troops southward into New Jersey where he was outmaneuvered by larger British forces commanded by more experienced officers. His desperate gamble crossing the Delaware River on Christmas night to launch a successful surprise attack on the Hessian garrison at Trenton, combined with his victory at Princeton on January 3, 1777, restored his reputation and that of his men. Nevertheless, he had his share of critics. For example, Maj. Gen. Charles Lee said that Washington was “not fit enough to command a Sergeant’s Guard.”

By the spring of 1777 the revolution in the American Colonies had settled into an uneasy stalemate with Washington and Howe each blocking the other from gaining any distinct advantage. “Washington is certainly a most surprising man, one of Nature’s geniuses, a Heaven-born general, if there is any of that sort … to keep a British general at bay, nay, even oblige him, with as fine an army of veteran soldiers as ever England had on the American continent, it is astonishing” wrote Nicholas Cresswell, a loyal British subject who had travelled in the American colonies before the Revolution and had visited Washington at his Mount Vernon home. “Washington, my enemy as he is, I should be sorry if he should be brought to an ignominious death.”

To break that impasse, in early 1777 Howe, commander of British troops in the American colonies, proposed several possible actions to Lord George Germain, Secretary of State for America, who was responsible for the conduct of the war. One of those proposed actions was an offensive against Philadelphia, the seat of the Second Continental Congress. Lord Germain approved Howe’s plan for the move against Philadelphia, although with fewer troops than Howe had originally requested. At about the same time, Lord Germain also approved a plan by General John Burgoyne for an offensive south from Montreal that, if successful, would open the Hudson River to the British and would sever New England from the rest of the rebellious colonies. It is worth noting that Howe also had suggested opening the Hudson, but by an offensive launched from New York City. In approving Burgoyne’s proposal, Lord Germaine’s expectation was that, if needed, Howe would assist Burgoyne by sending troops north from New York City.

In the spring of 1777, Washington moved his army from its winter quarters at Morristown, New Jersey, to a fortified position in the Watchung Mountains of northern New Jersey. Around the same time, Howe began a series of unexplained maneuvers that may have been intended to draw Washington out of the mountains and onto terrain more favorable for a general engagement.

If that was the purpose of Howe’s maneuvering, it failed. Washington would not be drawn out of his mountain stronghold. In July the British began loading troops into ships commanded by Howe’s brother, Admiral Richard Howe, in New York harbor while Washington tried to decipher Howe’s intentions. That same month, Washington also learned that Fort Ticonderoga between Lake Champlain and Lake George had fallen to Burgoyne’s troops as they advanced south from Canada. The surrender of Ticonderoga sparked an outcry from the American public, which had been led to believe the fort was impregnable. Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair, commander of the fort, and his superior, Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, commander of the Northern Department, each faced a court martial over the fort’s loss but both were eventually exonerated.

On July 24, Washington heard that Howe was sailing south and became convinced that his destination was Philadelphia. Washington marched south himself and stopped near Germantown just north of the city where he waited for Howe to commit himself. It eventually became apparent to Washington, however, that Howe intended to land his forces at the head of Chesapeake Bay, 55 miles south of Philadelphia, and march north. What became known as Howe’s Philadelphia Campaign had begun.

On August 24, Washington with Lafayette at his side led the army through the city of Philadelphia. His army was “twelve deep and yet [taking] above two hours in passing by,” Adams wrote. “We have now an army well appointed between us and Mr. Howe, [and] I feel as secure as if I were at Braintree [Massachusetts], but not so happy.”

The next day, Washington, again accompanied by Lafayette, scouted to within two miles of Howe’s army before returning to Wilmington, Delaware, where the American army was then camped. Then, early on September 9, he arranged his force to meet the advancing Howe on the high ground east of Brandywine Creek. The ground Washington had chosen allowed him to check an advance against any of the principal fords on the creek. The American commander placed a force of 800 light troops under Brig. Gen. William Maxwell west of the creek along Nottingham Road. Washington’s center on the east side of the Brandywine was under the command of Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene. His right wing was under Maj. Gen. John Sullivan, and on the left, where there seemed little possibility of any threat because of the nature of the ground there, he placed 1,000 Pennsylvanians under Maj. Gen. John Armstrong.

The first shots of the battle were fired on the morning of September 11 at Welch’s Tavern three or four miles west of Brandywine Creek when a British column ran into an advance party Maxwell had sent forward to probe the enemy. The Americans quickly withdrew back toward the main body of Maxwell’s men, who took cover behind a cemetery wall, fired on the advancing British, and then slowly fell back until they reached the creek where they were reinforced by Lt. Col. Charles Porterfield’s Virginians. Two heavy British guns and two 3-pounders were brought up and began firing at Maxwell’s men. In the meantime, Captain James Wemyss’ Queen’s Rangers and the 23rd Regiment flanked Maxwell’s men, driving them out of the woods and forcing them to fall back across the creek at 10 am.

British troops and artillery assembled on the creek’s west bank, and British and American cannons exchanged fire. “Though the balls and grapeshot were well aimed and fell right among us the cannonade had but little effect partly because the battery was placed too low,” said a Hessian captain.

While that was going on, British and Hessian troops formed a line on the high ground west of the creek and heading down the slope onto the low ground near the water. British officers straightened their battle line, but the firing slacked off.

Meanwhile, Howe and Lt. Gen. Charles Cornwallis had swung left with two battalions of grenadiers, two squads of light dragoons, guards, dismounted dragoons, and infantry on the Great Valley Road and crossed the creek well north of Washington’s position. When Washington became aware of Howe’s movement, he and his generals were appalled at what they considered Howe’s terrible blunder in dividing his forces and moved to exploit it.

Washington ordered Sullivan, Maj. Gen. William Alexander, and Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen to cross the creek immediately and attack the rear of Howe’s column on the Great Valley Road. Meanwhile, Washington and Greene would launch a frontal assault against Lt. Gen. Wilhelm von Knyphausen’s Hessians while Armstrong’s militia attacked his right flank.

Washington was doing in effect what he blamed Howe for doing, which was dividing his forces. About that time, however, Sullivan sent a dispatch to Washington informing him that there was no enemy column marching to the Americans’ right and that information received earlier must have been wrong.

Despite the earlier sightings, Washington and his staff accepted Sullivan’s letter as the truth and the attack orders were cancelled. At 2 pm a civilian named Thomas Cheyney, who resided in the area and who supported the rebel cause, rode hurriedly into Sullivan’s lines. He had been atop a local hill, he said, and had seen the British not a hundred yards away. They were already across the creek and heading toward the right of the American position, he said. Cheyney was taken to Washington where he sketched a map in the dirt showing the position of the British.

Washington was incredulous and may have feared that Cheyney was a Tory trying to entice him into making a false move. But as he pondered the situation, a courier arrived from Sullivan stating that the enemy was in their rear. They had been spotted on the heights and were estimated to be about two brigades in strength, Sullivan’s message said. The earlier sightings had been right.

“In a few minutes the fields were literally covered with [British soldiers],” said a local man who stumbled on the British near the American position. “Their arms and bayonets being raised shone as bright as silver, there being a clear sky and the day exceedingly warm.”

After receiving Sullivan’s note, Washington immediately ordered the divisions of Sullivan, Stephen, and Alexander to shift to meet the threat. Lafayette also was sent to aid Sullivan in any way he could. The Americans under Sullivan formed up on the slopes of a small hill south of Birmingham Meetinghouse facing the British, who were formed in three divisions on Osborne’s Hill. Sullivan’s four pieces of artillery were also positioned. “The damn rebels form well,” said Cornwallis.

At 4 pm the British marched in formation down the slope of Osborne’s Hill and toward the Americans, their bands playing their traditional marching song, “The British Grenadiers.” They first made contact with bayonets only on Sullivan’s left, where three Maryland regiments broke and fled.

When von Knyphausen heard the cannon fire from Howe’s flanking attack, which was said to be so loud it was heard in Philadelphia, it was his signal to attack across the creek, and his guns opened on the American position.

The battle would be on two fronts, but the heart of the fighting had by now developed on the right near the Birmingham Meeting House where 6,000 British troops were moving on Sullivan’s American troops.

“There was a most infernal fire of cannon and [musketry],” wrote a British captain. “Most incessant shouting…. The balls plowing up the ground. The trees cracking over one’s head [and] the branches riven by artillery.”

Washington quickly sent Greene with the reserve to back up Sullivan and hold the road to Philadelphia should a retreat became necessary, and then he rode quickly to the scene of Sullivan’s engagement where the Americans were still holding out. Lafayette, who had raced ahead of Washington, was in the thick of things.

For a hundred minutes the fight raged with “cannon balls flying thick and many and small arms roar[ing] like the rolling of a drum.” Finally Stephen’s division on the American right, where the fighting had been especially hot, fell back and a general withdrawal was signaled. The retreating Americans ran into Greene column, which let them pass and then stood against the pursuing British before falling back. Greene’s men made another stand at Sandy Hollow and after about 45 minutes of heavy fighting they again began falling back.

During the fighting there Lafayette was shot in the leg but, ignoring the wound, he tried to rally the faltering troops and organize a more orderly pullback before having his wound treated. Meanwhile, at Chadds Ford von Knyphausen had launched his attack. “The [American] battery played upon us with grapeshot, which did much execution,” wrote a British ranger. “The water took us up to our breasts and was stained with blood.”

The British were able, nonetheless, to break through the divisions in the American center commanded by Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne and Maxwell, forcing them to abandon most of their cannons and retreat. About the same time, Armstrong’s militia on the American left, which had never been engaged in the fighting, also abandoned their positions.

As darkness fell, the British attack came to a halt. The Americans were fleeing in an unorganized mob, all distinction of division, brigade, and company lost. They thronged the road heading toward Chester until after about 12 miles they reached a bridge over Chester Creek. There Lafayette, his wound still untreated and wearing an improvised bandage, had posted a guard to stop the stumbling mob and try to restore some order to the retreat. Washington and Greene soon arrived at the bridge, and the American army encamped with some order restored. It was then about midnight.

On the morning of September 12, Washington marched east from Chester, crossed the Schuylkill River, and camped near Germantown still between the British and Philadelphia, while Howe remained camped at Chadds Ford.

No casualty list for the American army at Brandywine survives and no figures, official or otherwise, were ever released. The nearest thing to a hard figure available from the American side was information given by General Greene, who estimated that Washington’s army had lost between 1,200 and 1,300 men. An initial report by a British officer gave similar figures claiming American casualties at more than 200 killed, around 750 wounded, and another 400 or so taken as prisoners. A member of Howe’s staff claimed that 400 of the American rebels were buried on the field, and another British officer wrote, “The Enemy had 502 dead in the field.” The Americans had also lost one howitzer and 10 field pieces including two brass guns that had been captured during the fighting at Trenton.

Howe’s report to Lord Germain said that the Americans “had about 300 men killed, 600 wounded, and near 400 made prisoners,” again agreeing more or less with General Greene’s estimate. The official report also listed 93 British killed and 488 wounded. Six enlisted men were unaccounted for. Only 40 of Howe’s casualties were Hessian mercenaries.

Washington had Lafayette’s wound treated by his own doctor and had the Frenchman transported by boat to Bristol, Pennsylvania, where he was visited by Henry Laurens, president of the Continental Congress, who personally escorted him to the hospital run by the Moravian Brothers in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Lafayette, who had turned 20 on September 6, was to remain there recuperating for two months.

When Howe was informed that Washington’s weakened American force was less than 10 miles away, he decided to press for another decisive victory. Likewise, Washington learned of Howe’s plans and began preparing for battle. The two armies squared off again on September 16 near the current site of Malvern, Pennsylvania, but before they could engage each other a torrential downpour let loose. With tens of thousands of the Americans’ cartridges ruined by the rain—and with his troops already outnumbered—Washington again retreated, leaving 1,500 men and four field pieces under the command of Wayne behind to monitor and harass the British as they prepared to move on Philadelphia. Howe, bogged down in the rain and mud, allowed Washington’s withdrawal. The affair has come to be known as the Battle of the Clouds.

On the evening of September 20, a more serious engagement occurred. About midnight, three British battalions under the command of Maj. Gen. Sir Charles Grey led a surprise attack on Wayne’s encampment near the Paoli Tavern. To ensure surprise, Grey had told his men not to fire their weapons but to rely on their bayonets. The British attack killed 50 of the Americans and took another 100 prisoner and was followed by claims, which were probably exaggerated, that the British had taken no prisoners and had granted no quarter. Wayne was able to extricate the rest of his men, however, and retired to join Washington’s main body.

The two armies maneuvered and counter-maneuvered until late in the month when Howe drew Washington north with a feint against the American supplies stored at Reading Furnace, crossed the Schuykill River, and by September 26 was in Philadelphia. By then, however, the Continental Congress had already fled, moving piecemeal first to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and then to York.

A year earlier, Washington had said the loss of Philadelphia “must prove of the most fatal consequences to the cause of America.” The city had now fallen, but in the year since Washington’s statement its value had lessened greatly. Congress and its records as well as most of the military supplies in the city had been safely removed. In addition, the city was 60 miles up the Delaware River from the ocean, and with the Americans controlling the river, Howe would have considerable trouble continuing to supply his troops.

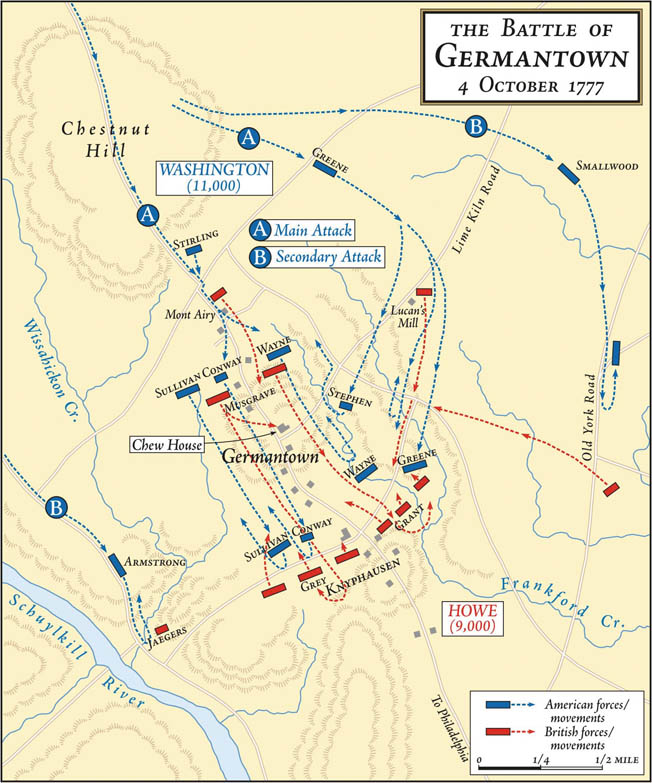

Concerned about the American control of the Delaware River and the supply problems that could cause him in Philadelphia, Howe stationed 3,000 of his best men in the city, another 3,000 across the Delaware River in New Jersey, and the remaining 9,000 men at Germantown to the west. When he received word of Howe’s division of the British army, Washington determined to attack the weakened British camp at Germantown and devised a plan that called for his force to advance in four columns along separate roads and then attack the British camp simultaneously.

Finally, in the evening of October 3, when Washington learned from two intercepted letters that Howe had dispatched a sizable detachment numbering approximately 3,000 men from Germantown to bring up supplies, he marched. Sullivan commanded the center-right column with Brig. Gen. Thomas Conway’s brigade on his right and Wayne’s brigade to the left. Greene commanded the center-left column. These two columns as well as Alexander’s reserve were made up of American regulars. The left and right columns were composed of militia commanded by Brig. Gens. William Smallwood and John Armstrong.

Washington’s plan basically called for a pincer movement in which the British main force would be smashed by Greene and Sullivan with Armstrong and Smallwood closing in on Howe’s right and left wings. It was a classic plan, one that Hannibal had used against Rome, but there were problems. Hannibal had put his strongest force on the wings while Washington concentrated his in the center, and even these men were largely recruits led by inexperienced officers and poorly trained militia. In addition, the plan called for the four American columns to approach in concert over four roads that were separated by up to seven miles of rough country without any communication among them,

The four columns were to charge with fixed bayonets at precisely 5 am, but the plan had made no provision for the stout wooden fences throughout the village, which would greatly hinder any proposed bayonet charge. Meanwhile, Howe had established his camp on high ground along Schoolhouse and Church Lanes at the southeast edge of the village. The western wing of the camp was under the command of the Hessian general von Knyphausen.

At 5 am on October 4, 1777, the vanguard of Sullivan’s column, commanded by Wayne, who was hungry to revenge the Paoli Tavern attack, launched the battle by opening fire on the British pickets stationed near Mount Airy just northwest of Germantown. Captain Allen McLane’s Delaware light horse scattered the British pickets, but they succeeded in firing off two cannons before fleeing. Those two cannon shots served to alert the rest of the British of the Americans’ attack.

Howe’s 2nd Light Infantry, joined by Colonel Thomas Musgrave’s 40th Regiment, hurried to the scene and engaged the advancing Americans. Together they stopped the American advance, but Wayne rallied his men and led them in a bayonet charge that drove the British back. The British in turn rallied and counterattacked the Americans. The fighting seesawed until a British bugle signaled a retreat.

“We charged them twice till the battalion was so reduced by killed and wounded that the bugle was sounded to retreat,” wrote a British officer. “This was the first time we had retreated from the Americans, and it was with great difficulty we could get our men to obey our orders.”

The British fell back slowly, fighting delaying actions at every fence, wall, and ditch. Howe had himself arrived on the scene and was chastising his men for falling back before what he still considered only an American scouting party. Eventually, however, American grapeshot scattered the leaves of a chestnut tree under which Howe was standing, scattering the officers to the delight of British enlisted men nearby.

“I think I never saw people enjoy a discharge of grape before, but we really all felt pleased to see the enemy make such an appearance and to hear the grape rattle about the commander-in-chief’s ears after he had accused the battalion of having run away from a scouting party,” wrote British Lieutenant Martin Hunter.

Meanwhile, the fog seemed to thicken and under its cover Musgrove was able to slip to the side and put six of his companies, 120 men, in a large stone house called Cliveden, which was the residence of Benjamin Chew, chief justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. From the windows of the house, Musgrove’s men were able to keep up a steady fire on Sullivan’s and Wayne’s men as they passed.

Washington and his generals met to discuss the problem the house presented, with some of them pushing to simply bypass it, but artillery chief Brig. Gen. Henry Knox, perhaps the most well read in military matters of the group, persuaded Washington that an enemy stronghold could not be left in their rear. The attacks on the house continued, and at one point Sullivan sent a white flag forward to ask for a parley. The flag was carried by Lt. Col. Matthew Smith of Virginia, who volunteered for the task. As he was approaching the house, however, he was fired on and hit. He later died of his wounds.

Incensed by the shooting of Smith, the Americans attacked with renewed vigor but were still unable to overwhelm the defenders. Maxwell’s brigade, which had been held in reserve, was also brought forward to aid in storming the house, and Knox positioned four 3-pounders beyond musket range and opened fire against the mansion. The artillery broke in the front door and smashed the house’s windows, but the stout stone walls resisted the bombardment. Two attempts to set fire to the building also failed. Infantry assaults launched against it were cut down, causing heavy casualties among the Americans.

Major General Stephen, commanding a Virginia division under Greene, heard the firing coming from the area of the stone house and deviated from plan without orders, swerving his division to march to the scene. There his artillery joined Knox’s in bombarding the house with no more success than Knox had had alone. Stephen was said to be drunk at the time and was later cashiered from the army for his actions at Germantown. Greene, who had been late arriving at Germantown, in the interim had attacked the British line with such vehemence that a bayonet attack by some of his men broke through to some tents behind the line and a large number of British prisoners were taken.

As this was occurring, Knox and Maxwell continued to launch futile attacks against the Chew House, and Sullivan’s division had pressed past the house in the fog. As Sullivan’s the 1st and 2nd Maryland Brigades advanced, they paused frequently to fire volleys into the fog, suppressing the British opposition but causing the Maryland troops to quickly run low on ammunition. Their shouts to one another for ammunition may have alerted the British troops to the situation and heartened them. Wayne’s brigade to the left of the road moved ahead and had become separated from Sullivan’s line when they also began hearing the firing of Knox’s cannons behind them. To their right, the firing from Sullivan’s men died down as the Marylanders ran low on ammunition. Fearing they had been cut off and surrounded, Wayne’s men began to fall back.

Sullivan was forced back also, although the regiments fought a stubborn rearguard action. As they pulled back, Wayne’s division collided with part of Stephen’s men in the fog and the two units began firing on each other before Wayne’s men retreated.

At about this time a cavalryman arrived at Sullivan’s column, yelling that they had been surrounded. Part of Sullivan’s men broke and ran, soon followed by the remainder. The officers were unable to restrain them. The British and Hessians who had been fighting Sullivan let the Americans run and turned their attention on Greene. Exhausted by the march and fighting, Greene and his men were forced to withdraw through the village using whatever hedges, fences, and stone walls they encountered as cover in what had turned into a rearguard action. By that point, the entire American army was in flight, and Washington’s attempt to rally the men was to no avail.

Maxwell’s brigade, still having failed to capture the Chew House, was also forced to fall back. Part of the British Army rushed forward and routed the retreating Americans, pursuing them for some nine miles before giving up the chase in the face of resistance from Greene’s infantry, Wayne’s artillery guns, and a detachment of dragoons as well as the coming of darkness. What had looked like an American victory had been turned into a defeat.

“The retreat was extraordinary,” wrote Patriot Thomas Paine, who was at the battle as an observer. “Nobody hurried themselves. Everyone marched at his own pace.” But he also wondered what had turned the victory into a defeat. “I never could, and cannot now learn, and I believe no man can inform truly the cause of the day’s miscarriage,” he said.

Of the 11,000 men Washington led into battle, 152 were killed and 521 were wounded. The official casualty report of the battle said that “upwards of 400 were made prisoners,” a group that included Colonel George Mathews and the entire 9th Virginia Regiment. Among the dead was Brig. Gen. Francis Nash, whose North Carolina Brigade had covered the American retreat. In all, 53 Americans had been killed in the ineffective attack on the Chew House. British casualties were 71 killed, 448 wounded, and 14 missing.

Lafayette recovered from the wound he had received during the Brandywine Creek fighting and returned to Washington’s army in November. After Brandywine, Washington had cited him in a letter to Congress for bravery and military ardor and recommended him for command of a division. When Lafayette returned to the army he was given the disgraced Stephen’s division.

As the year wound to an end, Lafayette assisted Greene in scouting British positions in New Jersey and, commanding 300 men, he beat a larger Hessian force at Gloucester, New Jersey, on November 24. After that he joined Washington’s army as it settled into winter quarters at its Valley Forge encampment north of Philadelphia. Over the next six months, the deaths in the Valley Forge camp from the harsh winter conditions and disease have been estimated as high as 3,000 men.

By the end of November, the British had overcome the American forts along the Delaware River and opened the waterway, but some good did come of the fights at Brandywine and Germantown, and even from that terrible winter at Valley Forge.

The following spring, Washington’s army emerged from Valley Forge in good order and better trained, thanks in part to a full-scale training program supervised by Prussian General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben during the winter. And, despite the American defeats at Brandywine and Germantown, international opinion as to the Americans’ fitness and the possibility of their toppling the British giant was rising. As Washington was fighting at Brandywine Creek and at Germantown, the Americans won a victory over the British at Saratoga in upstate New York. The Americans were encouraged by the victory at Saratoga and by Washington’s solid showing in the Pennsylvania engagements. Importantly, France’s attention had been caught. What earned the respect of the French was Washington’s switch to the offensive after the setback at Brandywine.

In 1778, France recognized the United States of America as a sovereign nation, signed a military alliance with the Americans, and went to war with Britain as well as providing the Americans with grants, arms, and loans. France also sent a French army to serve under Washington. Importantly, a French fleet in 1781 prevented Cornwallis’s British army from evacuating its encampment at Yorktown, Virginia, and the British commander surrendered on October 19.

Representatives of the newly created United States of America and Great Britain signed the final version of the Treaty of Paris, which recognized American independence, on September 3, 1783. Although the British had withdrawn their last troops from the American South in 1782, it was not until November 25, 1783, that the last British troops left New York bound for home.

After the American Revolution, Lafayette returned to France where he served in several governmental positions, commanded the National Guard after the French Revolution, and later refused to serve under Napoleon. He did, however, serve in the French government after Napoleon’s fall.

As for Washington, he was unanimously elected first president of the United States in 1789, serving two terms before returning to his home at Mount Vernon in March 1797. Although he lost the Battles of Brandywine and Germantown, his boldness, tenacity, and strategic acumen were on full display during the two battles.

This story was originally published in Military Heritage magazine.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments