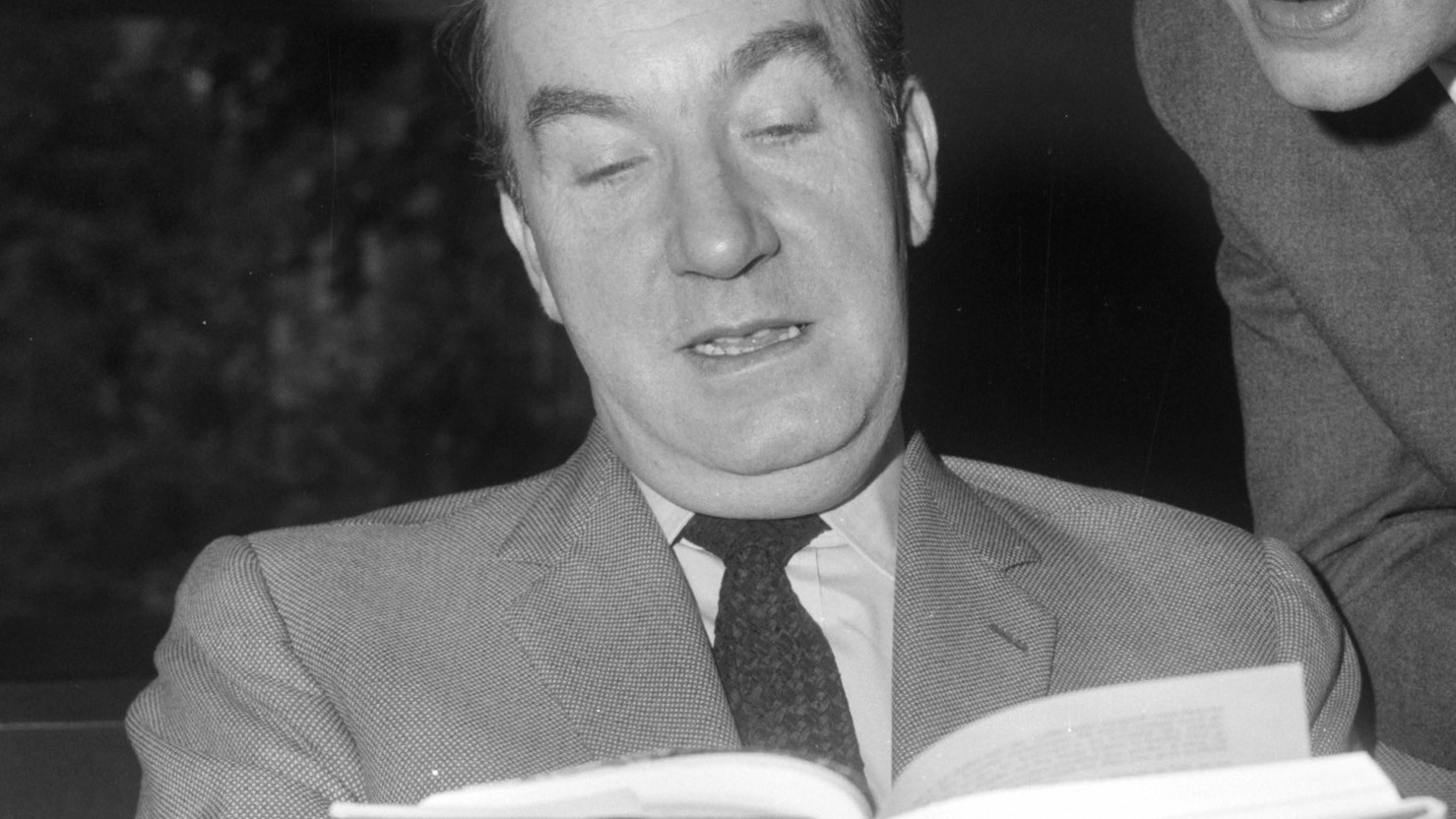

Anyone interested in reading military history sooner or later comes around to Cornelius Ryan, known to his friends as Connie. He wrote stunning books on World War II: The Last Battle, about the struggle for Berlin; A Bridge Too Far, about the ill-fated race to cross the Rhine bridge at Arnhem in 1944; and, of course, the book with which his fame will always be linked, The Longest Day.

Oddly, The Longest Day was published a bit later than it was hoped in 1959, the 15th anniversary of the invasion of France, and another book on the great battle was released a few months before. But being “scooped” made not the least difference. Critics and admirers of outstanding reporting saw the quality of the book and rallied to it. Military histories were forever altered, and improved.

Ryan was the son of a British soldier and an Irish-nationalist mother. His grandfather had been an irascible journalist in Ireland and young Connie soon determined journalism for his own career. Still in his early 20s, he was sent by a London newspaper to cover American G.I.s in Britain. At first he found it difficult, but later admitted that, “Among those brash, irreverent, confident [American] soldiers, I found my spiritual home.” He viewed D-Day from a ship in the invasion fleet.

Pursuing journalism in the United States after the war, he finally persuaded Reader’s Digest to underwrite his effort to write a book for the 15th anniversary of the Normandy invasion. He flung himself into the work, interviewing not only Americans, Canadians and British, but also French and Germans.

One of his best friends was Jerry Korn, who was a bomber copilot on D-Day and met Connie at Collier’s magazine after the war (and who later was managing editor at Time-Life Books when it produced its series on World War II in the 1980s as well as edited A Bridge Too Far). “The thing that made Connie’s book [The Longest Day] succeed was the scope of the research,” he told me once. “He talked to so many of the men that you really did get a sense of what it must have been like to have been there. Nobody had written anything like it. It’s a bit hard to appreciate now what a literary bombshell that was.”

Ryan was 39 when The Longest Day was published. He matured as a writer through his later books. But research was always a strong suit. Korn says he had file cabinets overflowing with material and millions of words of interviews and materials from which to shape his narratives. Supposedly Ryan once said, “I am a reporter. If I am some help to serious historians, I’ll be satisfied. I’m not a great writer, but I know how to combine a vast amount of material into a dramatic context. There is no reason for history to be dull.”

Ryan died of prostate cancer in 1974 at age 54, books he had wanted to write forever unrealized. Veterans of the 82nd Airborne acted as the honor guard at his funeral. General James Gavin presented his widow with the American flag that covered his coffin. Walter Cronkite read from The Longest Day.

Ryan often visited cemeteries in Normandy. There he once said to his wife, “Nobody knew their names until I began research for The Longest Day.… I guess I wrote The Longest Day because I never understood why nobody seemed to care about the names of the ordinary men and the civilians involved. If I ever did anything right in my life, I made their names immortal.” n

Brooke Stoddard

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments