By Michael D. Hull

He was a seagoing J.E.B. Stuart who hid beneath weather fronts to make his attacks, and he fought more naval engagements than John Paul Jones and David Farragut combined.

Engaged in every major naval battle in the Pacific Ocean during World War II, except the Coral Sea standoff of May 4-8, 1942, he introduced or sponsored most of the intricate tactics used by the U.S. fast carrier task forces to defeat Japan. And he helped to build the biggest naval air arm in the world.

Marc A. Mitscher was a pilot, a brilliant tactician, and the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s senior carrier admiral—recognized belatedly as one of the leading combat officers in the history of air-sea warfare. But his name, like that of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, the victor of Midway, never became a household word because he, too, was a reticent man who did not court publicity.

Unlike some of his contemporaries in the Pacific Theater, “Pete” Mitscher shunned self-imagery, never gave a speech he could avoid, and destroyed his private papers before his death. To some in the Navy, he seemed remote and baffling. But to those who served over, with, and under him, he was regarded as a fighting admiral of skill, courage, and human understanding.

His career spanned the 20th-century growth of American naval aviation, and he spent most of his lifetime preparing to fight air battles over the ocean. He understood both the sea and the air masses above it.

A Shy Boy in Oklahoma

The second child of Oscar Mitscher, a high-strung mercantile clerk of German extraction, and Myrta, his quiet-spoken wife of English stock, Marc Andrew Mitscher was born on Wednesday, January 26, 1887, in Hillsborough, Wisconsin. The family moved to dry, windy Oklahoma City, where Oscar opened a haberdashery and then a general store.

Marc’s childhood was a happy one. He went on hunting trips and rambles across the plains with his father, learned to play bridge and poker, and relished the big pots of noodle soup his mother made for him. Obedient and gentle, the boy loved his parents, though he seldom showed his feelings. Marc rode bareback on a frisky Indian pony and got into fights because of a frilly suit his mother made him wear on special occasions.

His grades were low in school, and he showed little interest in anything besides horses, baseball, and football. One of Marc’s teachers said he was shy and that he “blushed easily and avoided girls of any age.” The boy was delighted when his father was appointed agent for the Osage Indian Reservation at Pawhuska in northern Oklahoma in 1900. The family moved there, and Marc, now a teenager, enjoyed chasing jackrabbits and watching tribal dances.

But Oscar Mitscher decided that the Indian school was not suitable for Marc, his sister, Zoe, and his younger brother, Tom. So, when W.S. Field, a former business partner, offered to arrange winter schooling for Marc and Zoe in Washington, D.C., Oscar agreed. Marc made use of the Fields’s large library, where he happily snacked on sugar toast while reading Dick Merriwell and other adventure stories. Slightly built but muscular, he played sandlot football.

During summers in the Oklahoma hills that Marc loved, he spent much of his time riding, camping, and playing with the Indian boys.

From Annapolis to the USS Colorado

His father, meanwhile, had decided that he wanted a son to enter the U.S. Naval Academy. Tom was not yet eligible, so Marc became the choice. He was a slightly built, towheaded young man with piercing light blue eyes and a quiet manner.

Oscar Mitscher enrolled Marc in a Washington preparatory school, secured an appointment at Annapolis, and enlisted the aid of a friendly congressman. A 1904 letter to the Navy Department signaled the beginning of Marc’s career.

At the age of 17, Marc sat for the Annapolis entrance examinations on June 22, 1904, and his prospects were not bright. He was at the foot of the class. A lackluster student, he chafed at the discipline and found the studies almost impossible. It was only his innate stubbornness that kept him going. He piled up demerits, rebelliously became involved in hazing escapades, and was forced to resign in March 1906.

His angry father told Marc to stay at Annapolis while he convinced his congressman friend to make a reappointment. Marc was allowed to reenter and start all over again in June 1906. He was chastened and sober, but not dispirited. He made new friends and collected more demerits for smoking, card playing, and disorderliness, yet he persevered and devoted all of his free time to his books. His marks were still low, but he displayed an aptitude in seamanship, gunnery, and naval warfare studies. After graduating 107th in a class of 130 on June 3, 1910, he requested and was granted an assignment aboard the USS Colorado, a Pacific Fleet cruiser based in Seattle, Washington. He joined her complement that July.

The Colorado was a spit-and-polish ship but a welcome relief for Ensign Marc Mitscher after the rigors of Annapolis. The grades in his fitness report rose, and officers and shipmates found him to be “calm and even-tempered.” But he still got into trouble. He spent a night in jail after a tavern brawl in Valparaiso, Chile, in the autumn of 1910, and narrowly avoided being booted out of the Navy after missing the last liberty launch to the Colorado at Chimbote, Peru.

Pursuing Naval Aviation

The year 1911 was an eventful one for Mitscher. At the May wedding of a comrade in Bremerton, Washington, he met the young woman he determined to marry. She was blonde, brown-eyed Frances Smalley, the daughter of a Tacoma lawyer. They would be wed in January 1913. Also, in November 1911, while the Colorado was steaming toward the Philippines, Mitscher recalled a British book on aviation he had read at Annapolis and requested a transfer to the Navy’s aeronautics branch. It comprised three rickety airplanes, six pilots, and a dozen enlisted men.

Marc’s request was approved by the Pacific Fleet commander, but the young man was urged to learn seamanship first. He sailed in the Far East and Central America aboard the cruiser USS South Dakota, the gunboats USS Vicksburg and USS Annapolis, the cruiser USS California, and the destroyers USS Whipple and USS Stewart. He gained engine room and gunnery experience and was eventually promoted to lieutenant (junior grade).

But he was still interested in aviation and never stopped firing off requests for transfer to aeronautical duty. These were consistently pigeonholed, but naval aviation was expanding. An office of aeronautics had been established, and a flying school was being set up in Pensacola, Florida. Finally, on September 7, 1915, when the destroyer Stewart docked in Bremerton, Mitscher received orders to report to the cruiser USS North Carolina, the Pensacola station ship, for aeronautics training. The usually reserved and dignified young lieutenant jumped for joy on the deck of the Stewart.

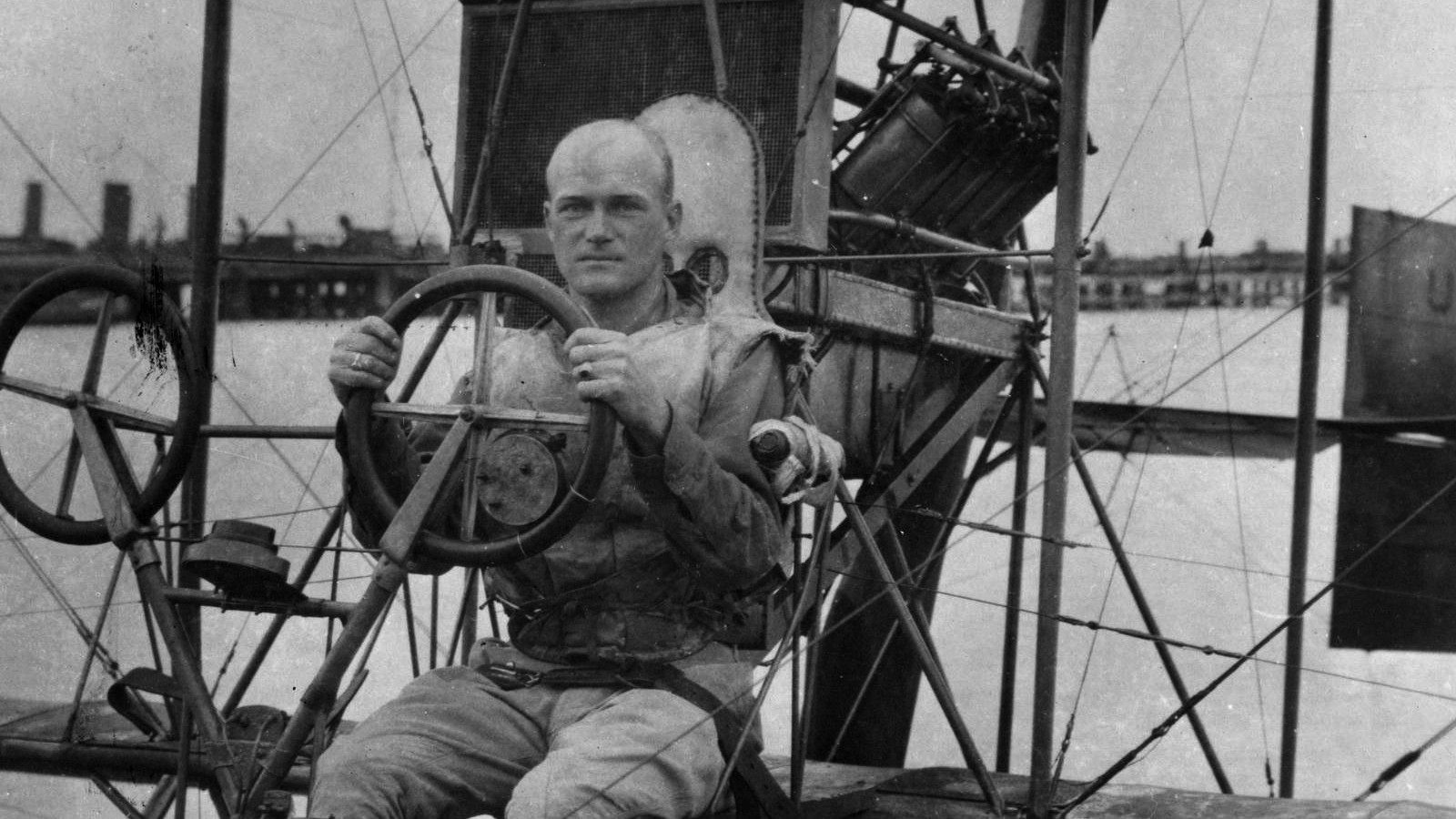

Reporting to the Pensacola flying school in October 1915, Mitscher was one of 13 students in the first formal class. He took his first airplane ride on October 13, and learned to fly crude wood-wire-and-fabric Curtiss, Wright, and Burgess-Dunne biplanes with 100-horsepower pusher engines and no cockpits. The pilot sat, strapped in, on the leading edge of the wing. Mitscher flew under instruction every day and methodically learned all he could. He excelled at Pensacola, and his fitness report cited his “eagerness.” He won his wings in June 1916, and was designated as Naval Aviator No. 33. He was then 29 years of age.

Mitscher, who found flying exhilarating but not glamorous, dedicated himself fully to the service. He became the Pensacola engineering officer and soon rose to command the naval air stations at Miami and Long Island, New York, when America entered World War I in April 1917. He saw no combat but took part two years later in a landmark operation—the first west-to-east attempt to cross the Atlantic Ocean by air.

“Pete” Mitscher’s Interwar Years

At the age of 32, balding and grizzled beyond his years, Lieutenant Mitscher was chosen in 1919 to fly with Lieutenant Patrick N.L. Bellinger in one of three big Curtiss “Nancy” flying boats—NC-1, NC-3, and NC-4—from Trepassey, Newfoundland, to England, with layovers in the Azores and Portugal. The three planes took off on May 16. The next day, Mitscher’s plane, NC-1, became lost in dense fog near the Azores, so Bellinger decided to set her down in choppy seas. NC-1 was disabled in the landing.

NC-3 also was forced to drop out, but Lt. Cmdr. Albert C. Read’s NC-4 was able to push on and reach Lisbon on May 27, and Portsmouth, England, four days later. The Americans were hailed in London, where Pete Mitscher was introduced to the Prince of Wales and Winston Churchill, the secretary of state for war and air. The fliers were later decorated by the Navy Department, and Mitscher was awarded the Navy Cross for “distinguished service.” But he was bitterly disappointed that NC-1 had failed to complete the historic flight.

After serving aboard the seaplane tender USS Aroostook, Mitscher led the San Diego air detachment in 1920-1921 and was promoted to lieutenant commander. From 1922 to 1925, he commanded the naval air station at Anacostia. Then, in 1926, came the break he had been awaiting. He was ordered to join the USS Langley, the Navy’s first aircraft carrier, and head her air department. A converted collier, the Langley was nicknamed the “Old Covered Wagon.” Six months later, Mitscher was appointed air officer aboard the new 36,000-ton USS Saratoga, the Navy’s third carrier.

“Remember Pearl Harbor”

After returning to the Langley and then the Saratoga as executive officer, he spent seven frustrating years waiting to realize his dream, a carrier command. In August 1941, he went to Norfolk, Virginia, as prospective commanding officer of the brand new, 19,900-ton USS Hornet. He was exhilarated.

Mitscher and his hand-picked staff were getting the carrier ready for sea when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, thrusting America into World War II. The skipper had missed out on the action in 1917-1918, but he would see plenty of it from 1942 to 1945. He had the words “Remember Pearl Harbor” painted in big letters on the Hornet’s smokestack, and she sailed from Norfolk at daybreak on December 27 for her shakedown cruise to the Gulf of Mexico. In February 1942, Mitscher was selected for flag rank.

The Doolittle Raid

Two months later, he and his ship made history in America’s first offensive action of the war—the audacious air raid on Japan led by the legendary Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle. On March 31, 1942, the Hornet docked at the Alameda, California, naval air station, across the bay from San Francisco, and 16 Army Air Forces twin-engine B-25 Mitchell medium bombers were hoisted aboard. They were the biggest planes ever to operate from an aircraft carrier, and rumors that they were being transported to Pearl Harbor were encouraged. The operation was planned with the tightest security.

On the morning of April 2, the Hornet steamed through the Golden Gate, outbound into the Pacific, with the cruisers USS Nashville and USS Vincennes, the oiler USS Cimarron, and screening destroyers. The carrier’s code name for the operation, chosen whimsically by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was “Shangri-La.” As the little Task Force 16 headed westward, Mitscher relinquished his bunk and cabin to Doolittle, and the two became good friends. Both were optimistic about the mission, and morale was high in the task force. The ships pushed on through heaving seas and squalls.

At 4:11 on the morning of Saturday, April 18, general quarters was sounded on the Hornet after unidentified targets had been spotted on the radar. It was decided to launch the B-25s before reaching the planned take-off point. Mitscher turned the Hornet into the wind, and the 16 bombers were warmed up on the flight deck. Doolittle waved goodbye, and Mitscher saluted him. Then Doolittle’s B-25 lumbered along the deck and into the air. The Hornet skipper watched anxiously as the other Mitchells followed at brief intervals. He was amazed that all took off safely.

Doolittle’s raiders dropped bombs on Tokyo, Yokohama, Kobe, and Nagoya. They inflicted only minimal damage, but the raid lifted American morale and alarmed the Japanese high command, causing it to seek a decisive engagement to destroy U.S. naval power in the Pacific. Mitscher believed that the Doolittle operation “paid big dividends, since it threw the [Japanese] islands into a panic and forced them to keep a large defense force at home, instead of sending them, as intended, to support the proposed invasion of Australia.”

The Most Decisive Naval Encounter Since Trafalgar

The Hornet returned to Pearl Harbor on April 25, and later headed for the Solomon Islands. She was too far from the Coral Sea to receive a baptism of fire in history’s first carrier battle and steamed back to Pearl Harbor. There, Mitscher was promoted to rear admiral on May 31. Meanwhile, a new commanding officer, Rear Admiral Charles P. Mason, was named to the Hornet. He had not had time to be “shaken down,” so Mitscher stayed aboard when the carrier sailed again, carrying 77 torpedo bombers and fighters. Her destination was the tiny American base at Midway atoll, 1,304 miles west-northwest of Hawaii.

There, the Hornet joined the carriers USS Yorktown and USS Lexington of Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance’s Task Force 16 to prevent Midway’s seizure by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s powerful Japanese fleet. During the furious battle on June 4-6, 1942, the most decisive naval encounter since Trafalgar, planes from the Hornet’s Air Group 8 and the other two flattops attacked and sank all four fleet carriers—Akagi, Hiryu, Kaga, and Soryu—of Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s strike force.

In one of the most valiant and tragic actions of the Pacific War, Lt. Cmdr. John C. “Jack” Waldron led 15 stubby Douglas TBD Devastators of the Hornet’s Torpedo Squadron 8 against the enemy carriers without fighter protection. The American planes were shot down by antiaircraft fire and Zero fighters, and only one member of Torpedo 8, Ensign George Gay, survived.

The venerable Yorktown was lost during the battle, but the American victory halted Japan’s southward expansion and was the turning point in the Pacific War. Pete Mitscher cared for his pilots and was particularly proud of Waldron. He nominated the men of Torpedo 8 for the Medal of Honor posthumously, but they were eventually awarded the Navy Cross. The losses at Midway deeply affected Mitscher, and the concern he felt for his men began to take a toll on his health.

Mitscher’s Rear Area Assignments

Mitscher left the Hornet for nine months of rear area assignments and then was ordered to the Solomons early in 1943 for his biggest task yet. After arriving on Guadalcanal, which had been secured that February by U.S. Marine Corps and Army troops, Mitscher took charge of air operations. Under his command were Army, Navy, Marine, and Royal New Zealand Air Force pilots flying an assortment of Grumman Avengers, Grumman Wildcats, Vought F4U Corsairs, Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, and Boeing B-17 bombers. They flew from four airfields.

It was a hectic, challenging time for Admiral Mitscher as he strove to upgrade defenses and living conditions for the pilots, secure much needed supplies, and shore up morale. He and his men huddled in dugouts and foxholes during punishing day and night Japanese air raids and endured heavy rains, mud, and malaria. On the humid, cloudy morning of April 18, 1943, the first anniversary of the Doolittle raid, a flight of Army Air Forces P-38s flying from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal intercepted and shot down a Mitsubishi Betty bomber carrying Admiral Yamamoto over Bougainville. The commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet was killed.

During his tough six-month tour of duty on Guadalcanal, Admiral Mitscher completed his assignment with flying colors. The bombers and fighters under his command downed 340 Japanese fighters and 132 bombers, sank 17 ships, and damaged eight. A total of 2,083 bombs were dropped by the Allied planes, and the enemy air threat to the Solomons was eliminated. But the strain was too much for Pete Mitscher. After malarial fever felled him for two weeks, his skin was yellow, his cheeks hollow, and his weight down to 115 pounds. Guadalcanal had left him physically and mentally exhausted. In late July 1943, he was relieved by Maj. Gen. Nathan F. Twining and ordered back to San Diego for a new command and recuperation. Frances Mitscher wept when she was reunited with her husband.

Admiral Mitscher’s post as commander of the West Coast Air Fleet provided him with a light workload and plenty of leisure time. He regained his health and spirits by hunting and salmon fishing in Alaska and the rugged Sierra Nevada range in eastern California, and, when his duties took him to Washington, by fishing in Maryland streams and the Chesapeake Bay. Inevitably, he grew restless for sea duty.

Marking time in San Diego as the year 1943 waned, Mitscher feared that he was perhaps being shelved at the age of 56. Yet, he was about to be given the biggest assignment of his career and one that would have a profound effect on the course of the Pacific War. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Pacific Fleet commander, and Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey Jr., commander of the Third Fleet, conferred with irascible Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, chief of naval operations, about a new commander for the fast carrier spearhead of the Third and Fifth Fleets. They agreed that Pete Mitscher was the best prospect. His air leadership on Guadalcanal had been impressive, he was arguably the Navy’s leading expert on naval aviation, and he was available.

Mitscher was notified of the command on December 23, 1943. Fit and eager for more action, he flew to Pearl Harbor a few days later and set up an underground headquarters on Ford Island. But soon his headquarters would be just a swivel chair on the wing of a carrier bridge.

Task Force 58/38

In January 1944, Mitscher assumed command of the new Task Force 58/38, comprising four task groups of 12 big carriers, battleships, cruisers, destroyers, fleet oilers, and ammunition ships. The fleet often included more than 100 ships carrying 100,000 men. Eventually, the task force included 15 flattops mounting 956 aircraft screened by eight new fast battleships and cruisers and destroyers. Mitscher’s command was designated TF-58 when it operated with Admiral Spruance’s Fifth Fleet, and TF-38 when it sailed with Halsey’s Third Fleet. With its composition remaining the same under each fleet commander, and equipped to remain operational for long periods, the powerful unit became the Navy’s primary strike force in the Pacific.

Putting to sea without delay, Task Force 58/38 started its combat service by establishing air supremacy over the Marshall Islands before the Marine and infantry landings there in January 1944. As it ranged across the Pacific, blasting enemy-held islands and coral atolls, Japanese naval and air units were unable to offer an effective defense against Pete Mitscher’s decisive force. His flattops were crowded with a total of 470 Grumman Hellcats, 199 Grumman Avengers, 165 Curtiss Helldivers, 57 Douglas SBD Dauntlesses, and Vought Corsair F4U night fighters.

The task force was engaged in almost all of the major sea actions and amphibious landings in the Pacific Theater, including Hollandia, the Marianas, the Philippine Sea, the Bonin Islands, Palau, Truk, Mindanao, Formosa, the East China Sea, Leyte Gulf, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. During the famous “Marianas Turkey Shoot” and the Battle of the Philippine Sea on June 19, 1944, Mitscher’s pilots claimed 395 Japanese carrier planes downed with the loss of only 130 American aircraft.

Wearing his trademark long-billed baseball cap and aviator’s brown shoes, and riding backward in a swivel chair on the wing of a carrier flag bridge, Mitscher whispered orders and ran his task force with deceptive ease. Confident and steady, he understood all facets of the complex air-sea operations and kept in close touch with the tactical situation by personally debriefing strike leaders and selected pilots after their missions.

His pilots loved him because he looked out for them. Knowing from experience what it was like to be ditched, he went out of his way to ensure that downed air crews were rescued. On one memorable night, Mitscher disregarded blackout safety regulations and ordered all task force lights switched on so that returning pilots could locate their carriers. “His fliers worshipped him,” observed the admiral’s chief of staff, the legendary Commodore Arleigh “31-Knot” Burke.

Mitscher seldom interfered with his task group leaders once they had their orders. He knew their capabilities and said simply, “I tell them what I want done, not how.” He grew to rely heavily on Burke.

Preparing for the Final Battles of the Pacific

After a well-deserved leave at home following the great Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, Mitscher returned to Pearl Harbor to help plan air strikes against the Japanese home islands and support the big invasions of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Then on December 18, 1944, while operating with Halsey’s Third Fleet in the Philippine Sea, Mitscher’s task force was caught in a raging typhoon. Three destroyers were sunk, and seven flattops and 11 destroyers were damaged. The casualty toll was 790 men.

Task Force 58 planes and ships’ batteries supported the 4th, 5th, and 3rd Marine Divisions’ landings on Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945, and air strikes were made on Tokyo. Then, Mitscher’s armada headed for the last enemy island stronghold, Okinawa, and Operation Iceberg. For more than 80 consecutive days at sea, from mid-March to late May 1945, Task Force 58 furnished direct support for Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner’s U.S. Tenth Army and the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions in their costly struggle to eliminate fanatical Japanese resistance.

It was during the climactic Okinawa campaign that Japanese kamikaze attacks against the U.S. and British Pacific Fleets reached their height. The Allied losses were 26 ships sunk and 160 damaged. After leading a charmed life, Admiral Mitscher’s flagship, the 27,200-ton carrier USS Bunker Hill, was struck by two suicide planes on the morning of May 11. She burned furiously and was badly damaged, with the loss of 396 men killed and 264 wounded. Several members of the admiral’s staff were wounded.

That afternoon, Mitscher—frail and weary from months of arduous duty—was lowered carefully down a Jacob’s ladder and transferred with a skeleton staff to the 19,900-ton carrier USS Enterprise. Three days later, she, too, was set afire by a kamikaze, and more of Mitscher’s aides were wounded. After the Enterprise and her task group withdrew for refueling, Mitscher and his flag were transferred again, to the 27,200-ton carrier USS Randolph. On May 27, he was relieved as task force commander by Admiral John S. “Slew” McCain. Pete Mitscher’s fighting days were over.

3,259 Japanese Aircraft Downed

The Navy Department announced in July that Task Force 58 had destroyed or damaged 3,259 Japanese aircraft in the Okinawa campaign, while Mitscher’s staff claimed 3,170. The admiral received high praise for his Pacific record. Admiral Nimitz stated, “It is doubtful if any officer has made more important contributions than he toward extinction of the enemy fleet.”

In a fitness report on Mitscher, Admiral John H. Towers said, “He has demonstrated to the world at large those outstanding qualifications of leadership and aggressiveness which I have always held in high esteem. I consider him one of the Navy’s outstanding flag officers.”

After meeting Admiral Mitscher on Ford Island, famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle observed, “I’ve been with the Army so long in Europe that I didn’t think the Navy had such human people. From now on, Mitscher is one of my gods.”

Pete Mitscher’s decorations included three Navy Crosses, the Legion of Merit, two Distinguished Service Medals, three Presidential Unit Citations, the British Order of the Bath, the French Croix de Guerre, and Belgian and Portuguese awards.

After returning home for a tearful reunion with his devoted wife, some restful fishing trips in the West, and an emotional parade in his Wisconsin hometown, Mitscher was appointed deputy chief of naval air operations in July 1945. He spent six days a week at his mahogany desk, all the time yearning to be back on a carrier bridge and far from Washington bureaucracy.

Pete Mitscher’s Post-War Career

On Sunday, November 18, 1945, Vice Admiral Mitscher was invited to the office of Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal. Mitscher went gladly because he admired the dynamic Forrestal, who was, like him, a former naval flier and a man of few words. After they had discussed the course of the postwar Navy and the Soviet threat to peace, Forrestal abruptly offered Mitscher the post of chief of naval operations, succeeding Fleet Admiral King. Mitscher was overwhelmed. No aviator had yet held the Navy’s highest command. But the carrier admiral declined. “No, thank you, Mr. Secretary,” he said quietly. “I’d want to make too many changes around here.”

Detached from the air operations post on January 31, 1946, Mitscher was promoted to four-star admiral and given command of the Eighth Fleet. His flag was hoisted on the 27,200-ton carrier USS Lake Champlain, based at Norfolk, Virginia. He was one of only two of the pioneering Pensacola fliers to achieve four-star rank (the other was Towers).

Mitscher became distressed when President Harry S. Truman proposed the unification of the armed forces, and he campaigned against it. But his spirits rose when he went back to sea in April 1946. Flying his flag on the new 47,000-ton carrier USS Franklin D. Roosevelt, he hosted Truman, Secretary Forrestal, and Admiral Nimitz during maneuvers off the Virginia coast. It was the first time a U.S. president had been aboard a carrier at sea. That summer, Mitscher also doubled as acting commander of the Atlantic Fleet.

Eventually, failing health caught up with Pete Mitscher. He complained of a cold while celebrating his 60th birthday on January 26, 1947, and a doctor admitted him to the naval hospital in Norfolk. It was believed that he was suffering from bronchitis, but a heart attack was soon diagnosed. President Truman sent Mitscher a wire, telling him to “keep your chin up and get well soon.”

But it was too late. Four years of war had worn out the frail admiral, and he died of a coronary thrombosis early on the morning of Monday, February 3, 1947. Commodore Burke reported, “The admiral has slipped his chain.”

Two days later, on February 5, Pete Mitscher was buried on the eastern slope in Arlington National Cemetery. A 17-gun salute echoed sharply in tribute to the gallant little warrior who shaped American naval aviation and led it to victory in the Allied crusade against fascist tyranny.

Fascinating article about an important, but little-known, man. I would note that the USS Lexington was not at the battle of Midway, having been sunk in the Coral Sea. The third US carrier was the USS Enterprise.