By John W. Osborn Jr.

Several Allied operations targeted a single enemy commander: the unsuccessful raid on General Erwin Rommel’s headquarters in North Africa to kill the Desert Fox; the assassination of the Butcher of Prague, SS Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia Reinhard Heydrich; and the shooting down of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s plane in the sky above Rabaul in 1943. But none of these combined the elements of danger and farce more than the kidnapping of the commander of German forces on Crete.

The idea to kidnap General Fredrich-Wilhelm Mueller was, somehow appropriately, hatched by two young officers in Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) over cocktails in Cairo in September 1943. For Captain Stanley Moss, just 18, it was the chance for some action. But for Major Patrick Leigh-Fermor, 20, there was a more driving motivation. He had been on Crete during the German invasion of 1941, been evacuated, then returned for 17 months as an SOE operative with the Crete resistance, seeing firsthand Mueller’s savagery against the Crete populace.

The resistance on Crete had recommended the operation a year before, and SOE Cairo agreed to Leigh-Fermor’s proposal. With two Crete SOE agents, Mainoli Paterakis and Georgi Tyrakis, Leigh-Fermor and Moss took off from Bardia in Egypt aboard a Vickers Wellington bomber bound for Crete the night of February 4, 1944.

“One General Was as Good a Catch as Any Other”

Things went wrong from the start. The drop zone over the Lashiti plain was so small that only one agent could jump at a time. Leigh-Fermor went first, but as the Wellington was making a wide circle for its next run clouds suddenly closed in, forcing it to head back south to Egypt.

Leigh-Fermor spent two frustrating months hiding with the resistance as eight more attempts by air and two by sea failed to land Moss, Tyrakis, and Paterakis. Finally, on the night of April 4, 1944, a motor launch was able to bring them close enough to Crete’s south coast to row ashore in a dinghy and join Leigh-Fermor.

The party marched across Crete’s mountains to the village of Kadtamonitza, where they met the SOE’s top agent on Crete, Micky Akaumianos. He had his own personal grudge against the Germans. His father had fallen while fighting the Germans during the 1941 invasion.

Akaumianos had disastrous news. Just two days before, Mueller had been replaced as commander on Crete by a decorated veteran of the Eastern Front, Maj. Gen. Heinrich Kreipe. (Mueller’s luck would be only temporary. He was hanged for war crimes in 1947.) Leigh-Fermor, despite the disappointment, decided to go ahead. As Moss later wrote, “We supposed that one general was as good a catch as any other.”

The Plan to Kidnap Kreipe

While Moss holed up in the nearby mountains with the resistance, Leigh-Fermor, who could pass for a native, and Akaumianos took a bus to the capital city of Herkalion. Both were disguised as peasants. From there, they walked five miles to observe Kreipe’s villa. Observing it closely, they determined that the villa was too heavily guarded for an assault.

From the nearby farmhouse of Akaumianos’s family, the agents kept the area under observation for a week. One day, as they walked the main road, Kreipe rolled by in his chauffeur-driven Opel. Leigh-Fermor and Akaumianos waved to him and, startled, Kreipe waved back. The episode gave them the idea for their attack.

Kreipe’s regular schedule made the general vulnerable. His car took him twice a day to his headquarters and back, the last time around 10 pm. They learned that he sometimes stayed even later playing bridge. They decided to stop his car at night and grab him, counting on the villa’s staff to assume he was playing bridge to give the kidnappers a few hours’ head start.

They returned to the mountain retreat outside Kasdtamonitza to inform Moss and the resistance about the plan. They recruited a local band of guerrillas to help, then marched to the village of Skalani five miles from the kidnap site, which was a hairpin turn in the road that would force Kreipe’s car to slow down. The guerrillas almost blew the operation when, bored by being cooped up for two days, they started wandering the area and had to be ordered back to the hills. With those members of the resistance already committed and two more reliable local policemen recruited, Leigh-Fermor and Moss had a final party of 11.

Kreipe Recalls His Capture

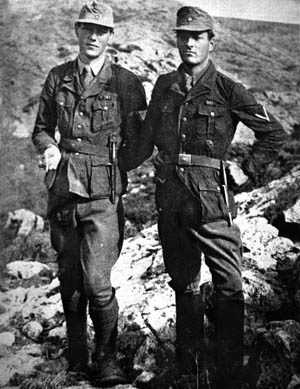

executing the plan to kidnap German General Heinrich Kreipe, British Captain Stanley Moss (left) and Major Patrick Leigh-Fermor are pictured in the mountains of Crete.

Akaumianos procured German uniforms for Leigh-Fermor and Moss so they could wave down Kreipe’s car while posing as sentries. The first three attempts to kidnap the general failed when he unexpectedly returned before dark. A fourth attempt was thwarted by rain. Finally, at 9:30 pm on April 26, 1944, the lookout spotted Kreipe’s oncoming car and pulled a wire running several hundred yards ahead to set off an electric bell and alert Leigh-Fermor and Moss to get into position.

“Suddenly,” Kreipe recalled a quarter century later, “a red light appeared in front of us, approximately on the bend. The chauffer asked: ‘Shall I stop?’ We were accustomed to traffic control patrols, and I answered, ‘Stop!’ As the car drew to a halt two lance corporals in German uniform stepped forward. One, Leigh-Fermor, demanded to see my travel document; as I did not have one—it was not normally required—I said: ‘Don’t know about that!’ ‘In that case, the password, please!’ Then I did something foolish. I got out of the car and said: ‘What unit are you? Don’t you know your general?’ (The car was showing the appropriate pennon and standard.) Leigh-Fermor, in his German soldier’s disguise, said: ‘General, you are a prisoner of war in British hands.’”

Kreipe was thrown to the ground, bound, and gagged while his driver, Sergeant Albert Fenske, was knocked out. As the men of the resistance dragged Fenske away into the hills, Leigh-Fermor, Moss, and Akaumianos squeezed into the front seat while Paterakis and Tyrakis piled on top of Kreipe in the back, holding a knife to his throat.

Wearing Kreipe’s cap, Leigh-Fermor saluted past 22 sentry posts. When they were far enough away, the party split, Moss and Paterakis to march Kreipe to their hideout in the Ida Mountains, Leigh-Fermor and Tyrakis to leave the car on the coast to make the Germans think the kidnap party had been evacuated by sea.

To spare the people of Crete from punishment, Leigh-Fermor left a note with the car: “to the German authorities in crete. Gentlemen, your Divisional Commander, General Kreipe, was captured a short time ago by a British raiding force under our command. By the time you read this he will be on his way to Cairo. We would like to point out most emphatically that this operation was carried out without the help of Cretans or Cretan partisans and that the only guides used were serving soldiers of his hellenic majesty’s forces in the Middle East, who came with us. Your General is an honorable prisoner of war and will be treated with all the consideration owing to his rank. Any reprisals against the local population will be wholly unwarranted and unjust. Auf baldiges Wiedersehen!”

He added a postscript: “We are very sorry to have to leave this beautiful car behind.” As further proof, he left a British commando beret, cigarettes, and an Agatha Christie paperback.

Transporting General Kreipe to Egypt

The Germans were not fooled, and soon 30,000 troops were scouring the island threatening reprisals while search aircraft flew overhead. One patrol came within a mile of the party’s cave.

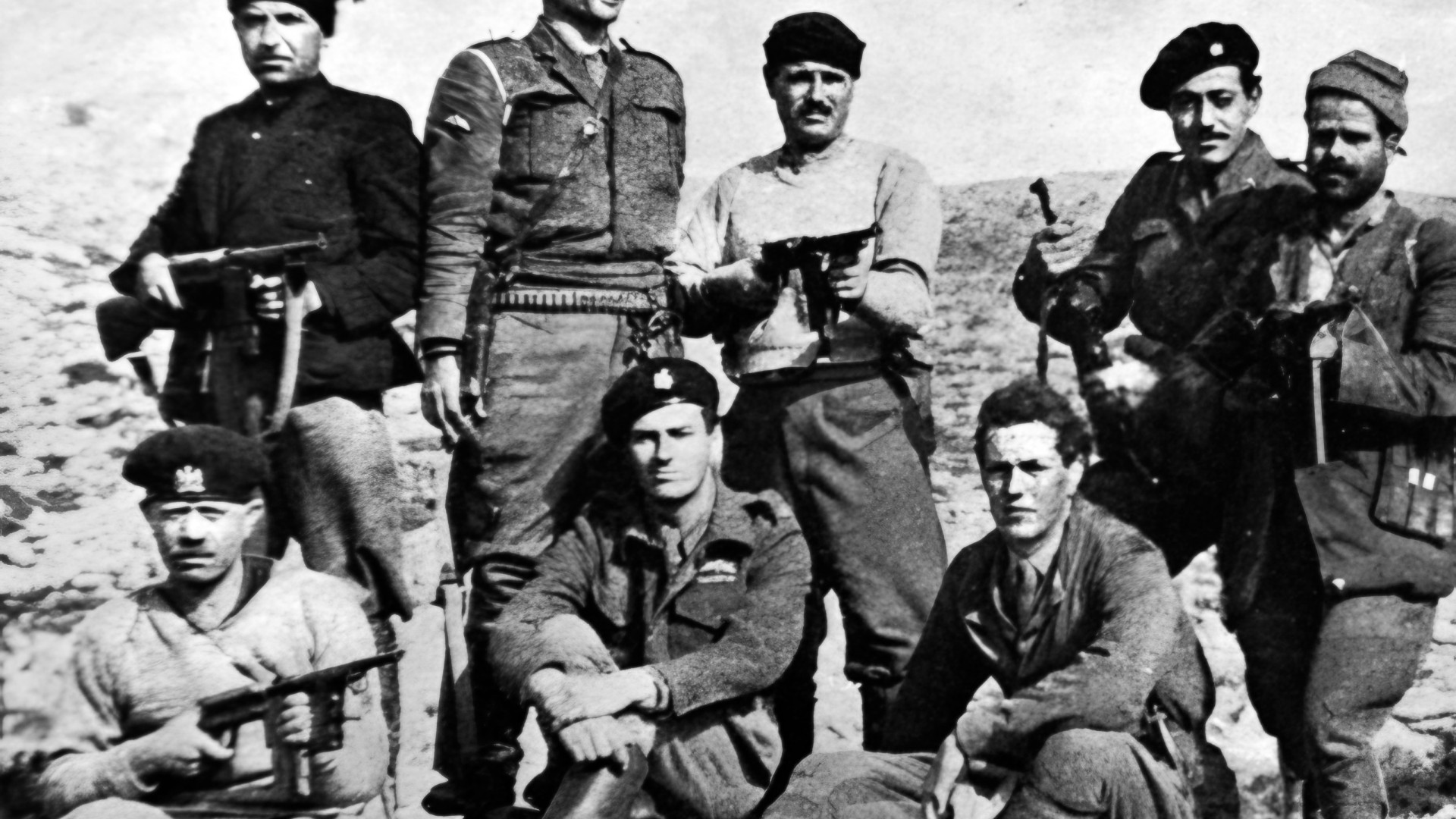

Moss (seated right) pose with several Greek partisans who participated in the kidnapping of German General Heinrich Kreipe on the island of Crete.

Kreipe would later admit that “after the brutal kidnapping, my treatment was on the whole correct.” He was certainly luckier than his driver Sergeant Fenske. When the resistance men turned up at the cave, he was not with them. They claimed he had died from his head injury, but it later came out that just a few miles from the scene they had cut his throat.

The first attempt to evacuate Crete was a near disaster. Just a few hours’ march from the beach, a Cretan messenger intercepted the party to report that German soldiers searching for Kreipe had unwittingly occupied the site. They marched back into the mountains to shelter in shepherds’ huts, while Leigh-Fermor sought an SOE radio operator to get new instructions.

A new beach site was radioed from SOE Cairo, and the final march to it turned into a triumphal procession with hundreds of partisans and peasants cheering along the mountain path and Kreipe swaying uneasily on his mule. After 17 nerve-wracking days on the run, at 11 pm, May, 14, 1944, the escape launch appeared. A unit of the British Special Boat Service commando unit landed to help fight their way off the island. The commandos were not necessary, however, and the party left Crete undetected.

On arrival in Egypt, the strain of the lengthy mission finally got to Leigh-Fermor, and he collapsed. He was decorated with the Distinguished Service Order in his hospital bed.

The Germans in the end took no reprisals. A resistance leader on Crete said, “Everybody felt taller by two centimeters. Out of 450,000 Cretans, 449,000 claimed to have taken part.”

Obviously less happy was Lieutenant General Kreipe (his promotion had come through the day after he was kidnapped). On his way to three years of captivity in Canada, he complained, “For a whole fortnight I had no clean handkerchief unless I first washed it in water!”

Peculiar that the movie as well as the book written by Moss is not mentioned. The movie, with the eponymous title, Ill Met By Moonlight, starring Dirk Bogarde and Michael Powell was made in 1957, and gives a fair account of this SOE triumph. I think it may be still available in the Criterion Collection.