By Stuart W. Sanders

It had been eight years since Jane Logan Allen’s husband, Colonel John Allen, had departed with his regiment. Friends and neighbors had stopped trying to convince her that she was a widow, yet Jane maintained hope of his return. Allen had been slain at the Battle of the River Raisin in the Michigan Territory. Every night since her husband had ridden away, Jane lit a candle and placed it on the windowsill to guide John home. Sadly, Colonel Allen never saw the flame.

At the Battle of River Raisin, fought during the War of 1812 in present-day Michigan, 400 Kentucky militiamen were killed. Following the struggle, nearly 65 of the wounded were brutally murdered by Indians who were allied with the British. Many of the dead Kentucky militia were led by Allen, an attorney and state legislator whose political prominence, had he survived, might have rivaled many national politicians, including that of fellow Kentuckian Henry Clay. But Allen’s career and his life were cut short at the River Raisin.

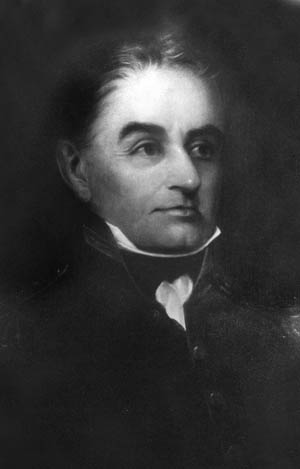

John Allen as Attorney

Allen was born in Rockbridge County, Virginia, on December 30, 1771. His father, James Allen, was a native of Ireland who emigrated to Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley with his widowed mother. James was educated in the best schools of the Great Valley of Virginia before pursuing business ventures in the West Indies. After securing a modest fortune, he returned to the Old Dominion, where he met and married Mary Kelsey. Their marriage was blessed with three sons, John, Joseph, and James. All made their mark on the Bluegrass State.

In 1779, the family moved across the Allegheny Mountains to the Kentucky frontier. They briefly stayed at St. Asaph’s, a fort at present-day Stanford, Kentucky, founded by the pioneer Benjamin Logan. Within a few days, though, the Allens moved approximately 10 miles away to Daugherty’s Station on Clark’s Run, near Danville.

The Allens felt confined by the close quarters at the station, and they and the Joseph Daviess family moved farther down Clark’s Run and built their own station. While living with the Daviess family, the eight-year-old John Allen befriended young Joseph Hamilton Daviess. Their careers and lives would closely mirror one another.

By 1784, new land beckoned, and James Allen again uprooted his family. James had cleared land near present-day Bloomfield in Nelson County, where he built a cabin and outbuildings. He returned to Clark’s Run to transport his family to Nelson County, but on reaching the property he discovered that Indians had burned all their cabins. Such was the hardship of the wilderness. The family rebuilt the buildings and made a permanent home in that area.

The family, like many Scots-Irish settlers, wanted their children to have a formal education. Therefore, in 1786, the 15-year-old John attended school in Bardstown. Located about eight miles from his home, the school was led by Dr. James Priestley, who was regarded as the most informed scholar of his day in the West. John learned the basics of Greek and Latin, a rarity on the Kentucky frontier. After Priestey’s school, Allen returned to Rockbridge County, Virginia, where he attended Liberty Hall Academy, the precursor to Washington and Lee University.

While in the Old Dominion, Allen met Colonel Archibald Stuart, a Revolutionary War veteran who studied law under Thomas Jefferson and ratified the U.S. Constitution as a member of the Virginia Convention. Stuart, who lived in Staunton, was impressed with the 20-year-old Kentuckian’s mind and education. Also likely intrigued by Allen’s frontier upbringing, Stuart invited Allen to live with him and study law.

Allen remained with the attorney for four years. As Allen progressed, Stuart allowed him to participate in legal cases, with Allen giving opening statements and making courtroom arguments. In 1795, his training complete, Allen returned to Kentucky, where he opened a practice in Shelbyville. He would prove himself to be one of the best of the profession at the time.

On a Path to Political Greatness

In Shelbyville, Allen met Jane Logan, the eldest daughter of Benjamin Logan. Logan was renowned on the Kentucky frontier, being an early settler, noted soldier, George Rogers Clark’s second-in-command, and an influential political leader. On December 21, 1798, John Allen and Jane Logan wed, and John and Jane eventually had four daughters.

In 1800, Allen was elected to represent Shelby County in the Kentucky House of Representatives. He served until 1807, when he was elected to the Kentucky senate. He was a state senator until the War of 1812 interrupted his political career and ended his life.

The most prestigious case in Allen’s legal career was in December 1806, when he and Henry Clay co-defended Aaron Burr. Burr, known for slaying Alexander Hamilton in a duel, was charged with putting together a military expedition against a friendly power and doing it within the jurisdiction and territory of the United States. The task before him was to try to wrest the Mississippi River states from Spain. Clay and Allen convinced the public that the charges against Burr were politically motivated by the Federalists, and Burr was cleared of the accusations.

During this case, Allen sparred in the courtroom with Joseph Hamilton Daviess, his childhood friend and classmate, who was Kentucky’s U.S. Attorney, prosecuting Burr.

With his legal reputation on solid ground and his business acumen growing, Allen hoped to reach greater political heights. In 1808, he ran for governor against General Charles Scott and Green Clay. During the campaign, Scott, an officer in both the French and Indian War and the Revolutionary War, argued that Allen’s oratorical skills were better suited for the U.S. Congress and not the governor’s chair. The public agreed, and Allen and Clay were trounced.

A Leader in the War of 1812

Soon Allen’s fellow Kentuckians chose him as a military leader. When the War of 1812 erupted against the British, Allen eagerly raised troops for the Kentucky militia. His abilities at military organization, coupled with his political influence, quickly earned him a high rank. On June 5, 1812, Allen was commissioned colonel of the 1st Rifle Regiment of Kentucky Militia. This was an honorable post, for it was the first Kentucky unit raised to fight in the war and would be later regarded as one of the finest of the Kentucky regiments. It would soon be tested in battle.

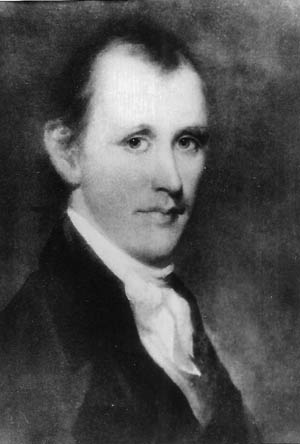

After Detroit fell to the British on August 16, 1812, Americans rallied to reclaim the settlement. Three columns of United States troops were dispatched to Detroit. One column, consisting of 1,300 Kentucky militia led by General James Winchester of Tennessee, moved to a rendezvous point on the Maumee River in present-day Michigan.

Pressing toward Detroit on a privation-filled march on January 10, 1813, the Americans stopped at the rapids of the Maumee River, located 35 miles from Frenchtown, a small settlement. Here, they were to wait for other American forces. The weather was frigid, provisions were low, and sickness was so prevalent in Allen’s regiment that the unit was only with the most difficulty restrained from disbanding and making the long journey back home. Soon, though, the cold and tired troops learned that two companies of Canadian militia and 200 Indians were at Frenchtown, where plentiful stores were rumored to be located. Therefore, instead of waiting for the other American soldiers, Winchester sent nearly 650 of the Kentuckians on a forced march to Frenchtown.

Winchester informed Maj. Gen. William Henry Harrison, the commander of the Northwestern Army, “I have this morning detached Colonel [William] Lewis and Allen with a command suitable to effect the object intended. I am informed that they will have to contend with two companies of Canadians and about two hundred Indians. If we get possession [of Frenchtown], it is my intention to retain it….” Upon reaching Frenchtown on January 18, the Kentuckians deployed before the small enemy garrison, which included fewer than 100 Canadian militiamen and 200 Potawatomi Indians.

“The Enemy Resisting Every Inch of Ground”

Captain Bland Ballard led an advance guard into Frenchtown. Behind Ballard, Allen’s three companies, totaling about 110 men, were posted on the right of the American line, with Major Benjamin Graves commanding the left and Maj. Gen. George Madison leading the center. Like Allen, these officers were also prominent. Both Ballard and Graves were state legislators, and Ballard, who lost his father, stepmother, and several siblings in an Indian attack, had reputedly killed nearly 40 Indians in revenge for these murders.

Graves deployed first, while the American right and center held. Allen started taking casualties, so he withdrew about 50 yards to get out of range of the Indians’ guns. Once Graves shoved another group of Indians into some woods, the rest of the Americans attacked. River Raisin survivor Thomas Dudley recalled, “As soon [as] the right and center reached the woods the fighting became general and obstinate, the enemy resisting every inch of ground.” In this sharp, three-hour fight, 12 Americans were killed and 54 were wounded, while the British lost about 30 killed, 50 wounded, and three prisoners taken.

Allen’s men and Lewis’s 5th Regiment of Kentucky Militia occupied the town, where the hungry Kentuckians found flour, beef, and wheat. They set up camp in an open field adjacent to the town, and, two days later, were reinforced by Winchester and 250 more troops, most of whom were a detachment of the 17th U.S. Infantry, also recruited from Kentucky. The regulars camped in another open field on the right side of the American position.

The next morning brought a melancholy mission when the Kentuckians went out of the town to retrieve the bodies of their slain comrades. Joseph Clark of Frankfort, who helped bury the dead, recalled, “All the men found—thirteen in number—were scalped and stripped of their clothing, their bodies frozen stiff, and presenting a horrible and sad sight. One of the dead only—a young Simpson or Shelby—escaped the scalping and stripping. Another had evidently been tomahawked and scalped while alive, as one of his fingers was cut off while he was protecting his head from the impending blow. The dead were brought to the village and buried in a mass grave.”

With the small settlement providing a few more comforts than the icy wilderness, most of the Americans remained camped in the open field near the town. They soon learned that more British troops were approaching. On January 21, Allen wrote a letter, which turned out to be his last, to Archibald Stuart, his former law instructor. “We meet the enemy to-morrow,” he wrote. “I trust we will render a good account of ourselves, or that I will never live to bear the tale of our disgrace.” His words were prophetic. Allen was killed the next day.

Breaking the American Lines

British General Henry Proctor, commanding about 600 Redcoats, 800 Indians, and several artillery pieces, was moving on Frenchtown. Although Allen’s letter shows that the Americans were expecting the British (a Frenchman had arrived on January 21 and told the Americans that the British were approaching from Fort Malden in Upper Canada, which was 18 miles away) the Americans made several basic mistakes. First, General Winchester was camped a mile from his troops, with his headquarters in a house on the other side of the River Raisin, which flowed on the south side of town. Second, because of the bitterly cold night no pickets were sent out to warn of the enemy approach. Therefore, when the British attacked at daylight they caught the Americans by surprise. Winchester’s mistakes can be attributed to the fact that he was an old Revolutionary War soldier who had little experience as an Indian fighter.

When Proctor reached Frenchtown, the Americans formed a line of battle, with Allen’s 1st Rifle Regiment placed on the left wing, behind a palisade or fence. Many of the Americans, including the 17th U.S. Regulars, were in an open field with only a rail fence for cover. When the fight began, the British pounded the American lines with artillery loaded with bullets and grapeshot. “Very many bombs were discharged by the enemy, doing, however, very little execution, most of them bursting in the air,” wrote Dudley. But the cannon fire did cause some casualties. Dudley noted that the regulars in the open field on the right side of the line suffered most, for these troops “had no protection but a common rail fence, four or five rails high. Several Americans on that part of the line were killed, and their fence knocked down by the cannon balls….” When the artillery stopped, the Indians rushed forward and tested the American lines, but were repulsed.

Soon, the British infantry advanced in formation, and the Kentuckians’ good marksmanship became evident. One Kentucky soldier fired, an English soldier wrote, “and hit Gates, the leading grenadier of the 41st [Regiment of Foot], right through the head. The ball went in one ear and out of the other.”

After about 20 minutes of fighting, the regulars on the right flank, unprotected except for the artillery-battered fence, fell back toward the river. Immediately, Allen and Lewis, each with about 50 men, left their defensive position behind the palisade and moved forward to help. Although they tried to rally other American units, both flanks were shoved back and Lewis was wounded.

The Redcoats pressed forward, the Indians encircled Frenchtown, and the American lines broke. Chased into woods by Wyandot Chief Roundhead’s warriors, a full-scale butchery ensued as the Kentucky troops were hunted down. At one point, as the Indians began to surround the fleeing troops, the Americans had to run a gauntlet down a path with Indians on either side, hidden in tall grass. Some who were able to reach the woods were subsequently surrounded and massacred, with about 100 of them slain by tomahawk.

The Death of John Allen

During the fight, Allen was severely wounded in the thigh. Despite his injury, the officer withdrew with his men, and, in several instances, attempted to rally the fleeing militia. It was no use, however, and the panicked rout continued. Exhausted after a two-mile retreat, Allen sat down on a log to rest. A pursuing Indian saw that Allen was an officer and was determined to capture him until the Kentuckian “threw his rifle across his lap.” As Allen barked at the Indian to surrender, another warrior burst through the woods and attacked. Allen ran the brave through with his sword, but a third Indian shot Allen in the chest, killing him instantly. After the fight, an Indian was seen walking around with Allen’s sword. Like many of the slain, Allen’s body was stripped and scalped.

Although most of the Americans were cut down, the Kentuckians on the left flank held out in Frenchtown, repeatedly driving off the British and Canadian troops until they were completely surrounded. The British promised that they would be treated as prisoners of war if they surrendered, and these soldiers gave up. Many of the unharmed prisoners were marched to Fort Malden.

Also among the prisoners was Solomon, Allen’s slave, who marched with the officer on the campaign, and Dr. Benjamin Logan, Allen’s brother-in-law. These men, however, were the lucky ones. Many of the wounded left behind suffered a horrific fate. The British lost 24 killed and 161 wounded.

Allen was dead, and other officers fell into British hands, including Winchester, who arrived late from his headquarters. Lt. Col. William Lewis, leader of the 5th Regiment of Kentucky Riflemen, was also captured. Both Winchester and Lewis were taken to Canada, where they remained until 1814. Winchester spent the next several years trying to clear his name regarding the River Raisin debacle, and he died, the stain of the defeat marring his military record, on July 26, 1826.

The Enduring Mark of the River Raisin Debacle

Four hundred Kentuckians were slain during the fight, including Robert Logan, another of Allen’s brothers-in-law. After the battle, once most of the British troops had departed, nearly 65 of the wounded Bluegrass troops were murdered by the Indians in Frenchtown, and many corpses were burned when the Indians ignited cabins containing dead or wounded.

On learning of the disaster at River Raisin, Kentucky Governor Isaac Shelby wrote, “This melancholy event has filled the state with mourning, and every feeling heart bleeds with anguish.” The fight, and the murders of militamen after the battle, indelibly marked the River Raisin on the minds of several generations of Kentuckians.

Had John Allen survived the War of 1812, it is probable that he would have risen to great political heights. As a successful legislator and attorney whose friends included Henry Clay, it is likely that he would have again entered the governor’s race. Other veterans, including multiple postwar Kentucky governors, used their 1812 military experience as a political steppingstone. With his previous political experience and connections, Allen’s service would have propelled him to higher office.

When assessing the casualties at River Raisin, Collins noted, “There was none whose loss was more sensibly felt or deeply deplored than Col. Allen. Inflexibly just, benevolent in all his feelings, and of undaunted courage, he was a fine specimen of the Kentucky gentleman of that day, and his name will not soon pass away from the memory of his countrymen.” Allen now lies buried in the cemetery in Frankfort, Kentucky.

Allen’s wife, Jane Logan Allen, who kept the lit candle on her windowsill for eight years, died on February 28, 1821. The grief that lay upon her took a heavy toll. Just before Jane passed away, she told her daughter, “John is come, the candle need not be lighted to-night.”

Interesting read I enjoyed reading it to the end. Including in this I am a descendant of Benjamin Logan’s brother Hugh Logan.