By Paul F. Braddock

For the second time in 13 years American troops are fighting in Iraq. Two hundred and thirty-five soldiers lost their lives during Desert Storm in 1991, and by the first anniversary of Operation Iraqi Freedom 570 soldiers had been killed. Over one hundred have died in Afghanistan since 2001. With American troops in over 110 foreign counties conducting UN police actions, guarding embassies, providing air support, and operating covertly, we know that surely more will lose their lives.

One thing stands out in reports coming from these various military operations: For the past 21 years—since Granada in 1983—not one serviceman or woman killed in action has been listed as unidentified. (A few men have been lost at sea and one pilot from Desert Storm has been listed as MIA/POW after his wrecked aircraft was located but not his remains.) For families, the loss of a loved one is hard enough, but they have at least one small comfort if the remains are returned.

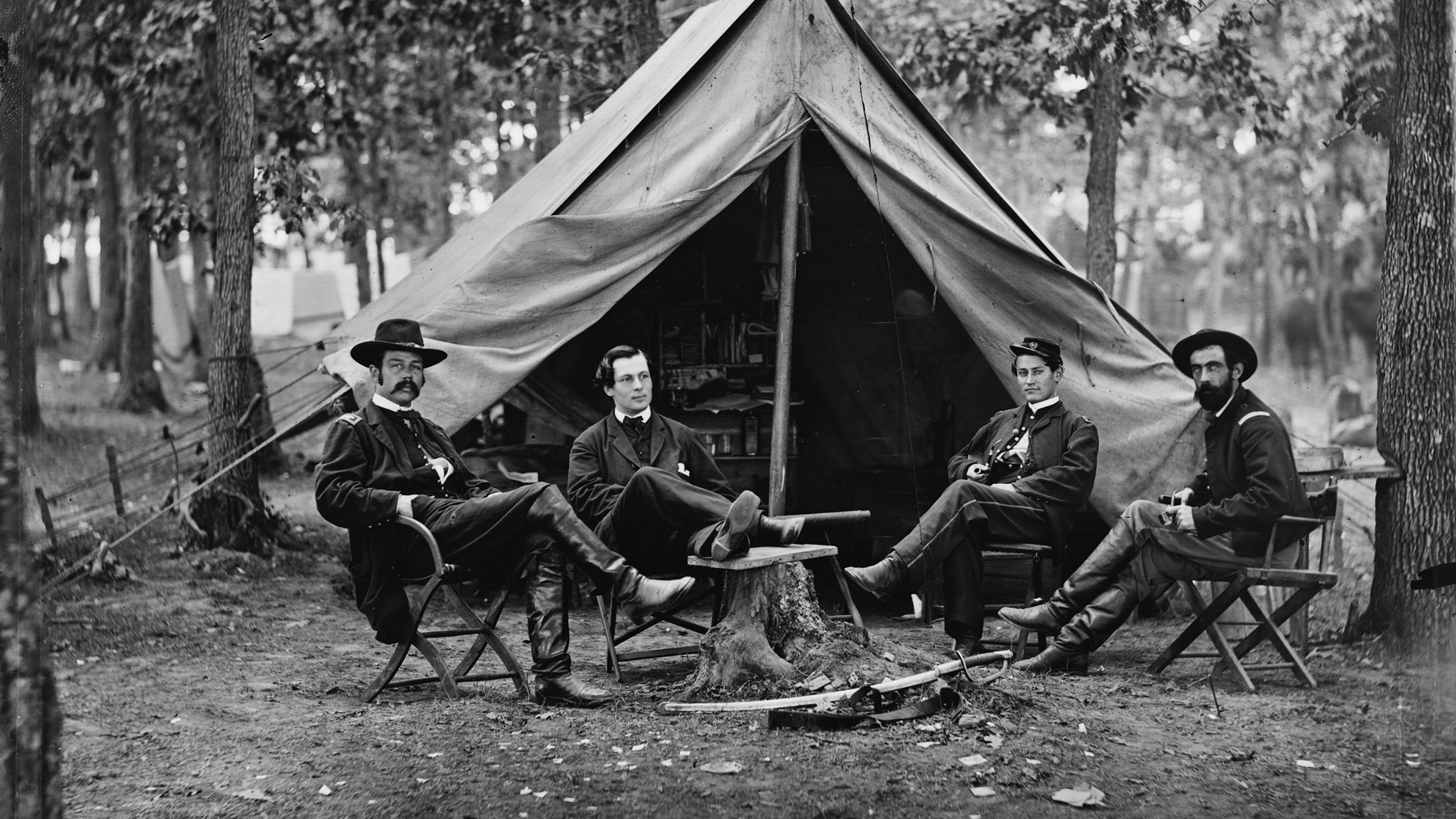

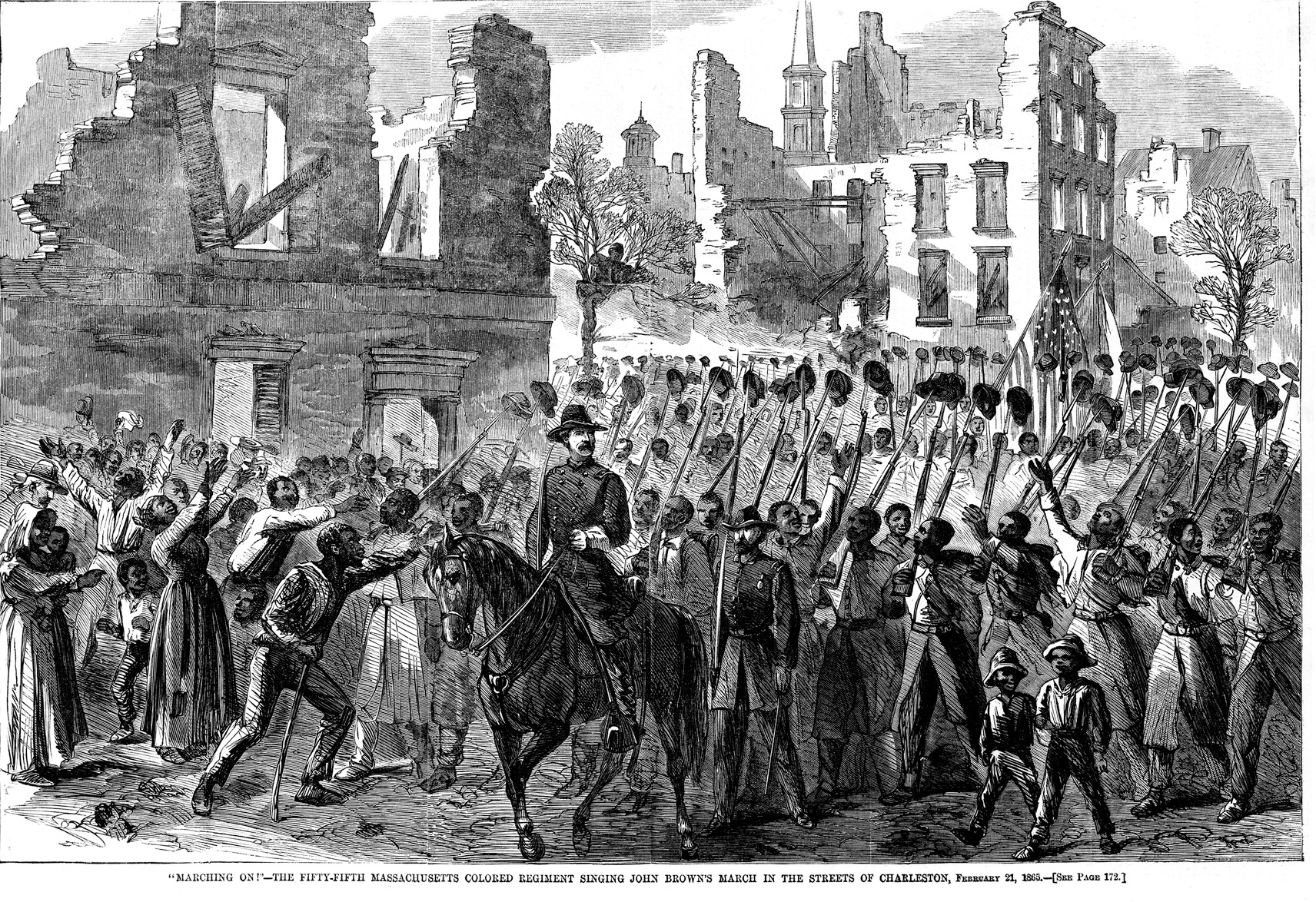

It was not always this way. In the American Civil War, 148,833 soldiers were unidentified, and of 70 sailors recovered from the wreckage of the USS Maine in 1912, all remain unidentified. At least 78,750 servicemen from World War II have never been recovered and 8,532 are interred as unidentified. The number not recovered from Korea totals 8,100 and 856 have been interred as Unknowns. From the Vietnam War, more than 1,800 still have not been recovered or identified.

These are large numbers, but the reason for the decrease in the number of unknowns over the decades —and thus the success rate of identifying soldiers’ remains—owes much to the identification system put in place by the United States military. Primarily, this consists of identification tags, now supplemented by DNA testing. In fact, the Pentagon began a program for the collection of blood and oral swabs for all military personnel then on active duty and for all those entering the services. A DNA data bank was established so the United States would never have an Unknown Soldier again. The tags, plus the DNA data bank, work.

It is also a known fact that recent searches for lost aircraft from World War II have—with both ID tags and DNA testing available—been successful in recovering the remains of lost airmen. Those found with their World War II identification tags intact have been identified, thanks to the durability of those small pieces of Monel or stainless steel, which have survived without rusting for 60 years.

The hobby of collecting identification tags, or “dog tags,” has in the past 10 to 15 years become increasingly popular. When I started collecting dog tags 39 years ago, as far as I could determine I was the only person openly advertising for tags from all services and time periods starting with the American Civil War. Now dog tags are genuine military collectibles.

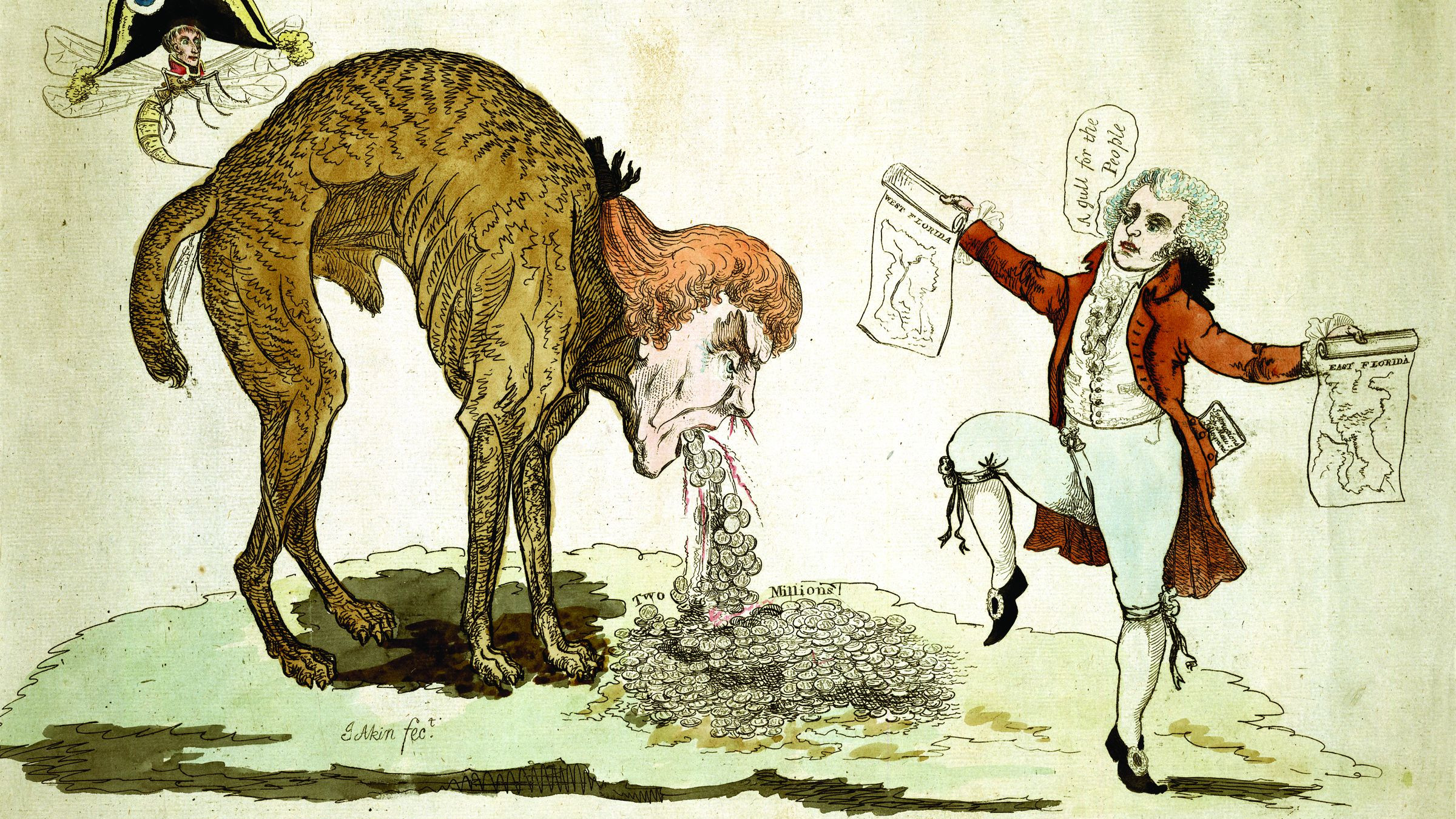

Identification tags in America began with the Civil War. Once the soldiers of that war saw how deadly service was becoming, they went to certain lengths to identify themselves. In part this had to do with the fact that widows could not obtain pensions from the government unless they could prove their husbands had been killed. Thus, Union soldiers pinned papers to their backs before the charge at Cold Harbor in 1864. Others privately bought any number of varieties of identification tags from sutlers in the field or from New York City outlets. In addition, Corps Badges (geometric shapes) were available in gold or silver and the name and unit of the wearer could be engraved on them.

A Civil War-era Identification Disc was also available in brass or pewter with a profile of George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, or a famous general. Other styles had patriotic sayings as part of their design. The soldier’s name and unit were inscribed, and some had an area where battles could be stamped on by the unit’s sutler. The words “War of 1861” or “War of 1861 & 1862” are commonly found on both the Corps Badge and Identification Disc, thus establishing the time period. In addition, some soldiers made their own “trench art” ID markers. I own one that is a carved bone neckerchief slide; it has the wearer’s initials and unit and corps insignia engraved scrimshaw style.

As in the Civil War, Spanish-American War soldiers had a desire to wear a means of identification, but the military made no effort to help—soldiers were on their own. In my collection is a silver ID badge obtained by a soldier from a local jeweler. In addition, the American Red Cross chapters of Oakland and San Francisco offered free small aluminum tags to soldiers leaving San Francisco for the Philippine Islands during the insurrection there. These showed the unit, company, and a roster number, but no individual name.

In 1906, the military began its first regulated system of identification. The first tag was of aluminum, 30mm in diameter, and embossed with metal hand stamps. The wooden cases that held the stamps had an instruction card attached to the lid showing how to stamp tags uniformly. The information placed on the tags included name, rank, company and unit, and the letters U.S.A. Their neat, uniform stamping style makes these century-old tags easy to identify.

In 1910, a new tag size was established. No formal regulation for this change has been found, but an instruction card attached to a 1911 stamping kit has the words “Model of 1910” written on it. The tag is the same as that of 1906, only larger, 35mm in diameter. Model 1910, or M1910, tags were worn by American soldiers in World War I. Up until this time, one tag—not two—was worn around the neck, but by June 1917, troops already in France received a second tag. These were 1 inch square and made of aluminum.

To the collector, World War I is a great period because of the variety of the tags and the information on them. For example, in 1918 the service number was created. These were often placed on the backside of an ID tag, although some appear on the front. Also in 1918, the tag size was reduced back down to 30mm, and regulations called for two holes. Five basic styles mark the World War I period. In addition, in 1917 the Navy issued its first tag. It was oval and made of Monel (a noncorrosive metal) and had the wearer’s fingerprint etched in acid on the back.

Following World War I, when soldiers reenlisted, their tag was given the prefix letter R to help distinguish them from new soldiers. This prefix letter was the first of some 80 prefix and suffix letters that would be used over the next 50 years.

In 1924, a style known as the M1924 was issued. M1924s were round and made of Monel metal. These and those used late in World War I were worn well into 1940-1941. The year 1939 saw another change, to a style of tags worn by millions of American men in World War II, Korea, and even Vietnam.

This new tag might be one of four types of metal—two of Monel and two of normal stainless steel—and it is the most common tag style to be found. It is oblong with rounded ends and a notch. This is not a tooth notch as legend has it, but rather an orienting feature for the hand-held printers used to upgrade medical records.

The Model 1940, or M1940, tag holds the soldier’s name, service number, tetanus inoculation date, blood type, address of next of kin, and a letter noting religious preference. (For medical reasons, the Army tried to give a tetanus booster shot once a year and wanted a record of it kept up to date on the soldier’s tags. If the man were wounded a medic could see if he needed an injection of tetanus toxiod to fight infection.) In 1943, the next-of-kin information was removed, reportedly for security reasons should a soldier be captured while fighting in Europe. This removal of next-of-kin information is one means by which a collector can date a tag. The tetanus date was also a great help until it also was removed in the mid-1950s—although it is worth noting that examples with tetanus dates into the early 1960s can be found.

The oval Monel tag used by the Navy in 1917 was still in use during World War II, not only by the Navy but also by the Marine Corps and the Coast Guard. Information was placed in three ways: all acid etched, stamped information with an acid-etched fingerprint, or all stamped. By 1955, every branch of the armed forces was using the M1940-style tag, noting branch of service by the letters USN, USMC, USCG, or AF.

In 1967 a new non-notch tag style emerged. It was worn by servicemen in Vietnam and is the style used today by soldiers in Iraq. The various branches still identify themselves as they have since 1955, but two changes cropped up in the Vietnam era. From 1969 to 1973, all services replaced the service number with the Social Security Number, and the blood group RH factor was added to the blood type for rendering better medical care if the wearer were wounded.

Collecting identification tags is not what it was before the Internet; eBay has added a whole new dimension. Now collectors bid against one another and prices have risen as a result. Common Civil War discs now start at $500 each and Spanish-American pieces, when found, can cost from $75 to $100 each. World War I tags with a unit stamped on them cost from $10 for a single tag to $20 for a matched pair. World War I Navy and Marine tags can cost from $25 to $55.

World War II Navy and Coast Guard singles and sets run from $5 to $25, depending on information and if a fingerprint is on the tag. Marine Corps tags are very popular, with prices for singles running from $40 to $70 each; sets go for $100 or more. Tags from Korea to the present day cost $5 to $10 for a single tag and at most $15 for a set.

Buyers should note that fakes work their way into the market. As with any hobby, once items become popular, the greed of a few creates genuine problems. As the old saying goes, “If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.” World War I Air Service tags and Marine Corps tags are especially popular and so should be looked at with greater care. Tank Corps tags should also be examined closely. Recent articles in newspapers relate tales of Vietnam period tags being produced for mom and pop stands in Vietnam then sold to travelers who bring them home in hopes of finding a veteran who had lost his tags many years ago. Personally, I have not run into this problem of fake tags being brought back to the United States.

In any case, this brief article gives a rough overview of dog tags, a subject that has captured my imagination for almost 40 years.

Paul F. Braddock lives in Pittsburgh, Pa., and is author of Dog Tags: A History of the American Military Identification Tag 1861-2002. He is a Company of Military Historians Fellow and a member of both the American Society of Military Insignia and the Association of American Uniform Collectors.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments