By Patrick J. Chaisson

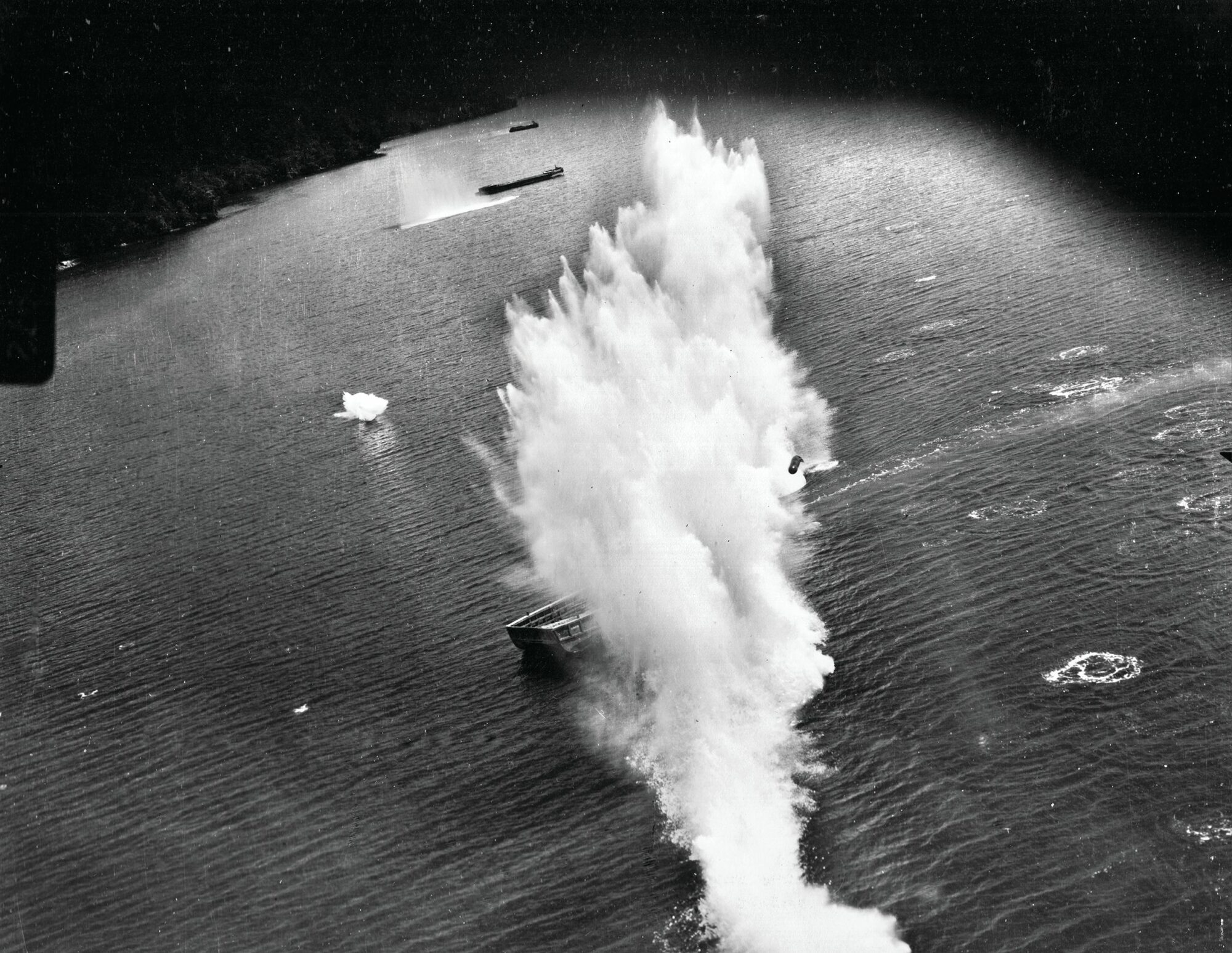

Wewak Convoy 21 was being annihilated, and the Japanese Army could do nothing to stop it.

The first vessel to die was Yakumo Maru. This 3,200-ton transport fell victim to two radar-equipped Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers of the 62nd Bomb Squadron, Fifth U.S. Air Force, some 60 miles off the New Guinea coastline at 0230 hours on Sunday, March 19, 1944. Going to the bottom with Yakumo Maru were 62 crewmen and 48 soldier-passengers.

After sunrise, at least 80 American warplanes returned to finish the job. Swarming over their weakly-defended target, the attackers quickly sank another 3,200-tonner named Taiei Maru plus two escorting subchasers. For the price of a few Douglas A-20 Havoc light bombers lost to antiaircraft fire, Fifth Air Force flight crews entirely obliterated Convoy 21, including its desperately-needed cargo of supplies and replacement soldiers.

The appearance of U.S. aircraft at precisely the right time and place to intercept these enemy merchantmen was no accident. Allied officers had been tracking the progress of Wewak Convoy 21 for days, aided by an Imperial Japanese Army order requiring every supply ship under its control to broadcast a “noon report” indicating that vessel’s position, speed, and heading as of 1200 hours daily.

In 1943, cryptanalysts stationed in Australia, India, and the United States cracked a super-secret enemy cipher known as the Japanese Army Water Transportation Code. Their stunning achievement generated a considerable amount of targeting data, all of which was promptly passed along to combat commanders. While many individuals contributed to this intelligence coup, one American sergeant deserves particular mention for his determination to do something positive during a time of great personal anguish.

Joseph E. Richard was born in Syracuse, Nebraska, on May 22, 1914, but moved out west with his family soon thereafter. After completing a three-year enlistment with the prewar California National Guard, Richard got a job at the Naval Supply Depot in downtown San Diego readying old destroyers for “Reverse-Lend-Lease” service with the British Royal Navy.

In April 1941, he received his draft notification. Scoring well enough on the Army General Classification Test to qualify for Signal Intelligence training, Richard reported to Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, where he eventually enrolled in the cryptographic (coding) school located there.

Joe enjoyed duty at Monmouth, and often spent his weekends in nearby New York City. That was where, on December 7, 1941, he learned that Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Together with a buddy, Private Richard stood at the entrance to the Holland Tunnel until a helpful cop flagged down someone willing to drive the soldiers back to base.

In January 1942, he was transferred to the Army’s Signals Intelligence Service (SIS). Richard recalled being sent “to Washington [D.C.] to work at the crypt office on the third floor of a wing of the temporary Munitions Building on Constitution Avenue.” One of his first tasks was to help move code materials from the overcrowded Munitions Building to SIS’s new home at a former girls’ school in Arlington Hall, Virginia. He spent several months at Arlington Hall, examining Japanese military radio messages that were intercepted by listening stations in the Panama Canal Zone, California, the Philippines, and Hawaii.

A part of the Army’s Signal Corps, SIS was organized in 1930 with William F. Friedman named as its first director. This brilliant scientist and his small team of analysts made cryptological history when they solved Japan’s diplomatic cipher, termed the “PURPLE Code.” Of note, it was SIS’s codebreakers who discovered that Tokyo had ordered its ambassador in Washington to cease all negotiations with U.S. officials effective December 7, 1941.

The SIS’s single-minded focus on PURPLE left little time for anything else. Consequently, the United States Army entered World War II almost totally ignorant of Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) radio communication codes. It took 18 months of mind-numbing toil before American cryptanalysts such as Joseph Richard began to make any progress against these sophisticated ciphers.

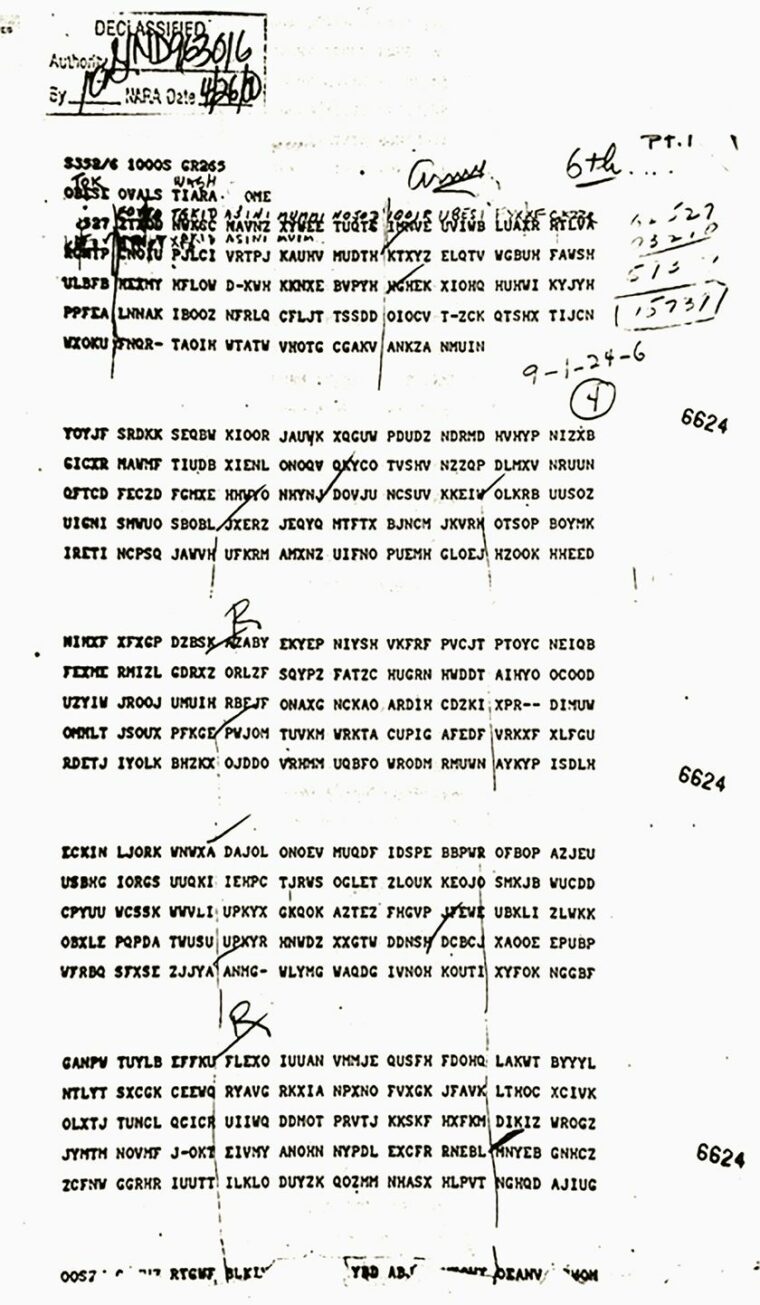

Japanese signal security officers responsible for safeguarding the IJA’s high-level communications employed a cryptographic system that substituted random numbers for words and numerals. To begin the encryption process, a clerk would look up in the Army Code Book each word that he wished to conceal. Alongside that word was a four-digit number, which the soldier then wrote down.

Listed in a separate part of the Army Code Book was a “key register,” another random four-digit number (changed regularly) which the clerk then added to each code number as a second form of security. When making his calculations, the Japanese soldier used “false” or non-carrying addition in a further attempt to confuse electronic eavesdroppers.

A typical encoding sequence might have started with the word “Shanghai.” In his codebook, a clerk first matched “Shanghai” with its number-substitute—8127, for example. Next, he enciphered that number code using the current key register—say, 6982. The result—4009 —was derived by adding both numbers together without carrying the tens.

To decrypt IJA messages, another soldier at the receiving station simply reversed the process using a codebook that was arranged numerically. Japanese commanders found it an awkward and labor-intensive system, but one they believed could not be breached.

It certainly seemed that way to the analysts at Arlington Hall, who spent the spring of 1942 in a futile attempt to figure out these number-codes. Joe Richard needed an occasional rest from his responsibilities, so in May he attended a servicemen’s tea on the White House’s South Lawn. A highlight of the event, he recalled, was when President Franklin D. Roosevelt came out to address the 500 enlisted soldiers, sailors, and Marines. Roosevelt’s talk inspired Richard to seek an overseas posting, and before long he was on a slow boat to Australia together with eight other novice codebreakers.

Now wearing the three stripes of a Technician Fourth Class, Richard arrived in Melbourne for duty with the 837th Signal Service Detachment. The officer in command there was Major (later promoted to Colonel) Abraham Sinkov. In appearance, this balding, bespectacled 34-year-old resembled a high school math teacher—which, in fact, was Sinkov’s occupation before William Friedman recruited him into the SIS.

Behind that unassuming façade, however, resided the mind of a cryptological genius. Abe Sinkov played a crucial role in defeating PURPLE, and in 1941 became one of the first Americans ever permitted to visit Britain’s super-secret decoding center at Bletchley Park. By July 1942, Major Sinkov found himself in Melbourne assigned to a mysterious multinational signal intelligence organization known as the Central Bureau.

Central Bureau was the brainchild of General Douglas MacArthur, recently named as Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area. Made up of British, Australian, and American codebreakers, its mission was to provide MacArthur with raw, unfiltered information on IJA activity throughout his area of responsibility. Naval intelligence came from a combined Royal Australian Navy/U.S. Navy fleet radio unit not under General MacArthur’s direct command.

At first, the American cryptanalysts assigned to Central Bureau struggled to keep up with their combat-tested British and Australian colleagues. Joe Richard deemed Royal Australian Navy Commander Eric Nave “an indispensable person” for that officer’s unparalleled skill in figuring out IJA air-ground communications codes. And veteran Commonwealth signals intercept technicians brought with them a technique called “traffic analysis” that could be used against the Japanese just as it had in the deserts of North Africa.

Traffic analysis involved the study of IJA radio networks in order to learn how the enemy was organized. Intelligence personnel scrutinized volumes of intercepted wireless communications, always alert for the presence of patterns in call signs, message priorities, and addresses. Experienced traffic analysts could reveal much about Japanese order of battle and even predict troop movements—all without decoding a single message.

By dint of much hard labor, signal intelligence specialists at Central Bureau began to part the veil of secrecy that cloaked IJA’s communications. Using traffic analysis and other techniques, Allied experts unraveled the code used by Japanese signalmen to identify locations—they now knew that any message with “9834” in the address label, for instance, was intended for commanders on Rabaul.

Technicians also identified four major radio networks in use by enemy forces. Of these, the Japanese Army Shipping Command used a circuit designated as “2468” to control its vast fleet of merchantmen sailing in support of IJA formations stationed all across Asia and the Pacific. Rushed into service, this Water Transportation Code was a simplified version of the Army’s number-substitution system intended for use by poorly-trained shipboard radiomen. Similar to the mainline code but lacking many of its special security features, the 2468 discriminant would soon receive close attention from Central Bureau’s team of Allied cryptanalysts.

In September, Australian “Diggers” began a counteroffensive against Japanese troops strung out along the Kokoda Track in New Guinea. To better support combat operations there, the staff of Central Bureau moved forward some 1,000 miles (1,600 km) from Melbourne to Brisbane that same month. Richard remembered partnering up with another American soldier for the journey, made in a vehicle loaded with photocopying equipment and file drawers. During the trip, he said, “One of us slept in the truck at night because the cabinets held classified material.”

Central Bureau established its Brisbane headquarters in a large house at 21 Henry Street in the suburb of Ascot. Joe remembered the two-story residence had “verandas around each floor,” which at some point were closed in “so our classified papers would not blow away.”

At the time, T/4 Richard and his fellow G.I.s were all attempting to batter their way into some low-level IJA codes using a crude trial-and-error method. This “brute-force” attack demanded an extraordinary amount of effort for no apparent result and caused a great deal of frustration among those analysts forced to hand-sort page after page of unintelligible radio intercepts.

Richard was sifting data on the upstairs veranda one November day when he heard a gunshot from an adjoining room. He rushed in to find his friend, T/4 John Bartlett, on the floor gravely wounded. A young officer had been instructing other servicemen on how to disassemble and reassemble their .45 caliber pistols when his weapon accidentally discharged. The bullet struck Bartlett (who had come in to ask for a weekend pass) in the abdomen.

Sergeant Bartlett was rushed to Brisbane General Hospital, but did not recover. His death deeply affected Joe Richard, who was shocked by this senseless tragedy. “I secretly resolved to do extra work to make up for John,” he recollected later.

Richard approached his boss, freshly-promoted Lt. Col. Sinkov, and volunteered to organize Japanese Army Water Transportation Code intercepts during his off-duty time. Telling Sinkov he “had a hunch that they would yield something worthwhile,” the grieving soldier was immediately granted after-hours access to these so-called “2468” files.

“I started sorting one evening late in January 1943 under a weak droplight and with the blackout curtain closed,” he wrote. “I continued this work almost every night for the next three months.”

Joe soon discovered a common peculiarity among the Water Transportation Code messages he was handling. “By about the third night of sorting,” he recalled, “I noticed that the first digit [in each four-number code group] was nonrandom.” This revealed a flaw in the 2468 system, which by design should have eliminated all such patterns.

An elated T/4 Richard “notified Col. Sinkov that the 2468 indicator was not behaving randomly.” Sinkov replied by telling the sergeant his discovery confirmed the findings of British cryptanalysts based at the Wireless Experimental Centre in Delhi, India. Codebreakers there regularly shared intelligence with Central Bureau and other Allied signals intelligence stations worldwide.

More information was required, so SIS and its powerful IBM tabulating machines joined the fight. Workers at Arlington Hall ran several months’ worth of Water Transportation Code intercepts through their mechanical sorters but failed to uncover any nonrandom characteristics. Sinkov and Richard learned of SIS’s disappointing conclusions shortly thereafter.

This troubled Joe Richard until he “remembered that the [key register] changed about every four weeks.” He concluded that “Arlington Hall must have mixed up two or three months’ traffic.” Richard mentioned this to Sinkov, and the tests were run again with messages carefully organized by date.

The rapid sorting made possible by SIS’s IBM pre-computers revealed additional patterns hidden within each Water Transport Code message. Analysts in Brisbane and Arlington Hall began to see relationships forming between many of 2468’s four-digit code groups, and pushed themselves in a friendly competition to finish the puzzle first.

Armed with reams of newly-processed data, Richard sat down after lunch on April 6, 1943, to organize these nonrandom numbers into s an enciphering square. He labored far into the night to complete this arithmetical problem but couldn’t quite make it add up.

“The solution kept slipping away from me,” Joe admitted, “as I was sleepy.” A supervisor, Captain (later promoted to Lt. colonel) Larry Clark, then stopped by to check on progress and helped talk Richard through his mental block. Together, the two cryptanalysts located the last pieces of information needed to finish their enciphering square. This time it worked perfectly.

Richard’s square provided a purely mathematical means of stripping off the key register, that additive number set used by enemy radiomen to disguise their four-digit codes for places, ships, time, and cargo description. Traffic analysis had already filled in some of the blanks; with its key register defeated, the Japanese Army Water Transportation Codebook now became a secret weapon in Allied hands.

Joe Richard went to bed that night happy his three-month task was finally over. While he slept, Central Bureau sent copies of his encipherment square to the other signals analysis stations whose cooperation made it all possible. “That afternoon,” Joe remembered, “we were somewhat deflated to receive a message from Arlington Hall saying that they [also] had the square.” Both agencies, 10,000 miles apart, had almost simultaneously arrived at a solution.

The trickle of information that Central Bureau was able to extract from Code 2468 now became a torrent. Before long, the three Japanese linguists on staff were so busy interpreting decrypted message traffic that extra translators had to be borrowed from the Navy’s fleet radio unit in Melbourne.

By August 1944, writes historian Edward J. Drea, U.S. Army cryptanalysts had deciphered 75,000 Water Transportation Code messages. Many of these intercepts contained such actionable intelligence as routes, sailing times, and freight lists—data that soon found its way into the hands of Allied naval and air commanders all across the Pacific Theater of Operations. As a result, hundreds of merchantmen and their valuable cargoes were destroyed, further diminishing Japan’s ability to hold onto its far-flung empire.

The conquest of Code 2468 did not entitle T/4 Richard to a long rest, though. He immediately began applying his knowledge of IJA’s Water Transportation Code to other ciphers, thus aiding the Allies’ effort to penetrate their enemy’s most secure mainline communications networks. Douglas MacArthur’s daring “leapfrog” campaign across the northern coast of New Guinea could never have succeeded without a thorough knowledge of Japanese strength and intentions derived from Central Bureau’s analysis of high-level radio intercepts.

These achievements did not go unnoticed. MacArthur’s Chief of Staff, Lt. Gen. Richard K. Sutherland, later claimed this ability to read Japan’s secret codes “chopped two years off the war in the Pacific.”

In the summer of 1944, Joe Richard received both a Legion of Merit and promotion to the rank of Warrant Officer for his work on IJA ciphers. Leaving the military in 1946, he took a civilian position with the Army Security Agency at Arlington Hall, Virginia, before joining the National Security Agency in 1952. Richard’s postwar career spanned 27 years, including duty as Assistant Chief of Station in the NSA’s Australia office. He retired in 1973.

In recognition of his exceptional contributions to the field of cryptography, Chief Warrant Officer Joseph E. Richard was inducted into the U.S. Army Military Intelligence Hall of Fame in 1993. He died April 8, 2005, and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

The inspiration for this article came from a visit to the US Army Military Intelligence Museum in Fort Huachuca, Arizona, during January of 2020. There on display was a small but important exhibition of T/4 Joe Richard’s cryptological victory over the Japanese Army Water Transportation Code in 1942-43.

Patrick J. Chaisson is a retired military officer from Scotia, New York. He gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Mrs. Lori S. Stewart, US Army Military Intelligence Corps Historian, in the preparation of this article.

Superb story! Thanks!