By Eric Niderost

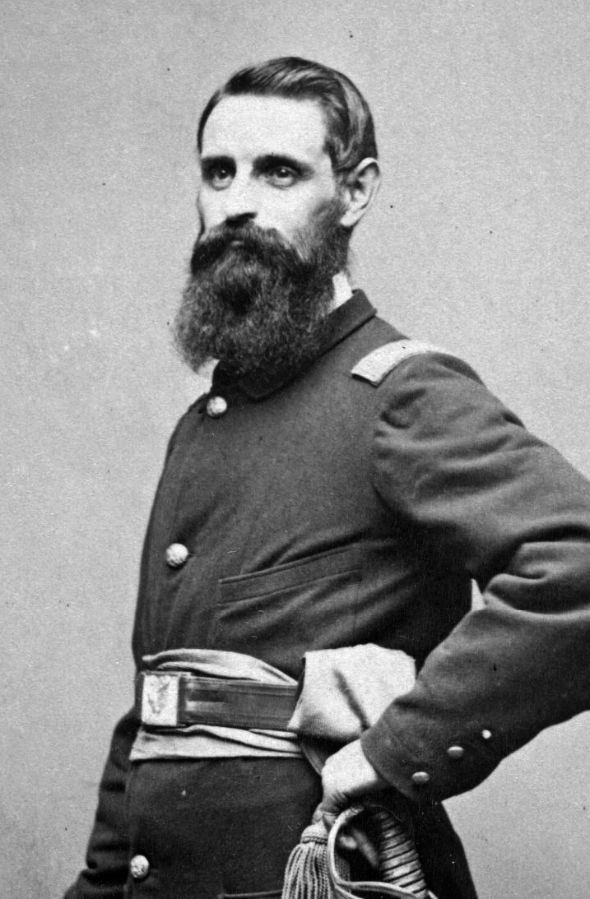

It was about four o’clock in the afternoon of July 2, 1863, when Colonel Ira Coray Abbott ordered his regiment to halt on a low rise called “Stony Hill,” near Gettysburg, a small town in southern Pennsylvania. Abbott and his men were part of a Union army fighting the invading Army of Northern Virginia under the celebrated southern General Robert E. Lee.

Abbott’s unit was the First Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment, First Brigade, First Division, Fifth Corps, the Army of the Potomac. It was the second day of battle, and it wasn’t clear which way things would go. The first day’s fighting had been confused, in part because elements of both armies had stumbled upon one another, and calls for help from hard-pressed units had drawn more and more formations haphazardly into the growing maelstrom.

The Federals were forced to fall back, abandoning Gettysburg in favor of establishing a defensive position on high ground just beyond. Taking and holding the high ground is a military axiom that has been followed for centuries, but Lee was sure he could overcome the Union position with a flanking movement on the Army of the Potomac’s left

Everyone knew that this unfolding battle might well determine the outcome of the war. Lee had won a series of notable victories against the long-suffering Army of the Potomac, most recently at Chancellorsville only a few weeks before. It seemed as if every time they suffered a defeat at Lee’s hands, President Abraham Lincoln would fire the commanding general and replace him with a new man. Right now the Army of the Potomac was led by General Gordon Meade, a Pennsylvanian who seemed competent enough, but had only been appointed to the command a scant three days before, and so was an unknown quantity.

But Abbott and his regiment were hopeful that Meade, nicknamed “the old snapping turtle,” might yet sink his teeth into the rebels and never let go. Perhaps the fact that they were fighting on his native soil might stir Meade to greatness. When he had time to jot a few words down in his diary, Abbott recalled the march to Stony Hill with fondness: “Our movement was in column by division, the 18th Mass (Massachusetts) on the right followed by the 118 Pa (Pennsylvania) and 1st Mich in the center & the 22 Mass in the left. This old brigade moved forward in splendid style feeling that victory was in our grasp… Our brigade reached the established line (Stony Hill) and deployed into line.”

Though he didn’t know it yet, Gettysburg was going to be the climax of a distinguished career that had begun when the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter in 1861. Thousands of Americans realized they were living through one of the most important periods in the history of the still young republic, and were determined to record events for future posterity. Abbott was one of them. Abraham Lincoln and other notable figures appear in the pages of the diary, but Abbott also records the day-to-day life of a soldier in the field—not just fighting, but trying to live as best as one can under circumstances far from normal.

Ira Coray Abbott was born in Burns, New York, on December 14, 1824. When he was 10, his father decided to pull up stakes and moved the family west. Americans have always been a restless people, seeking greener pastures beyond the horizon. The epic migration to Oregon and California is the stuff of legend, but in the 1820s and 1830s the American Midwest was the promised land to people in the more settled eastern seaboard.

The Abbott family moved to Buchanan, Michigan, where young Ira attended public school. His father was a farmer, a common enough occupation in those days, but he must have prospered, because he was able to send his son to a business college in Elkhart, Indiana, for a year. After graduation Abbott, now a young adult, found work as a clerk in a bank and general store. Marriage followed in 1857 when he wed Electa Shear. Two children were born, and the Abbotts seemed to look forward to a future of domestic tranquility as members of the rising middle class.

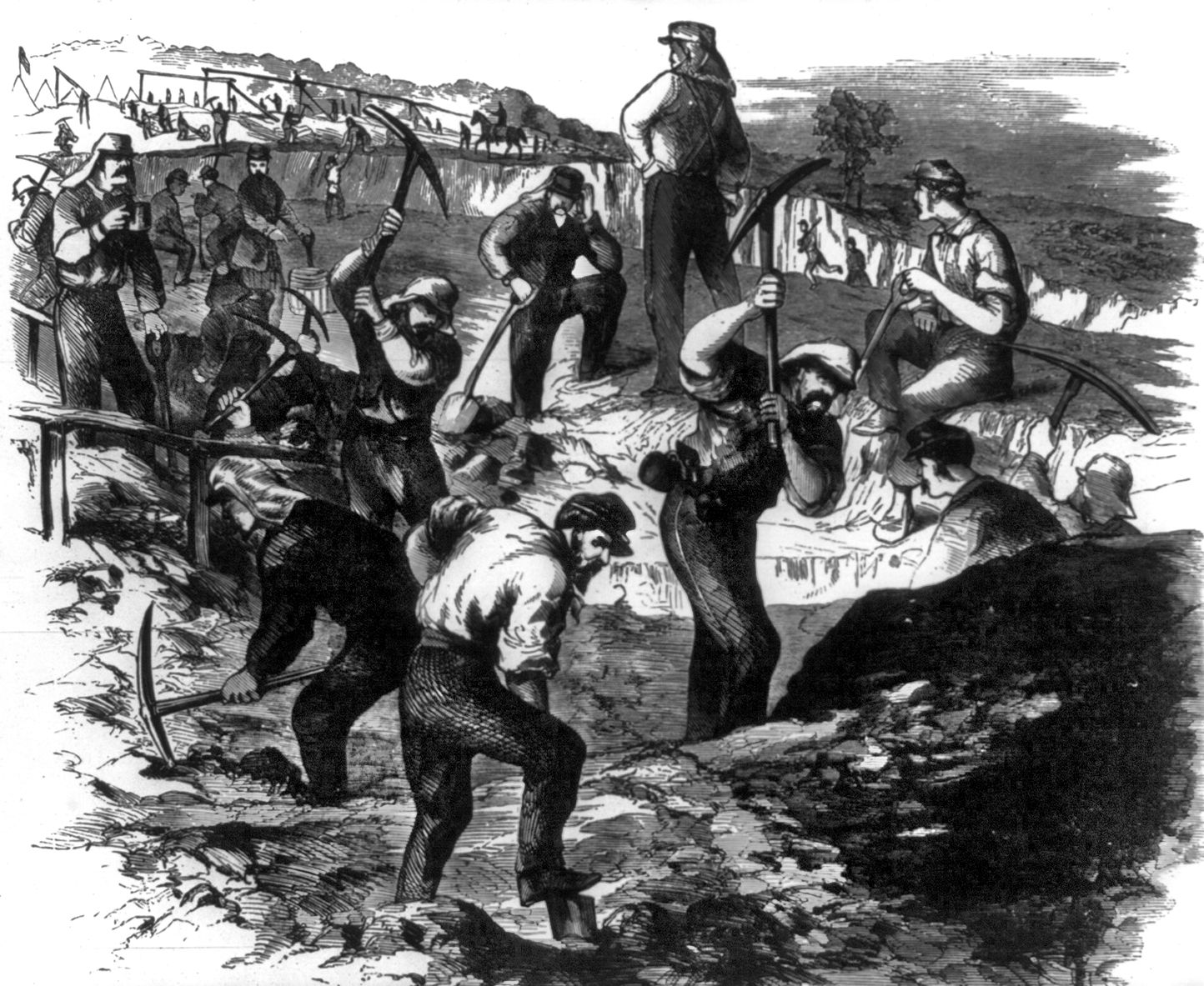

All that changed after Fort Sumter. Lincoln responded by issuing a call for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion. Each loyal state had its own quota to fill, and the enlistment term was set at three months. Michigan, a staunch unionist state, responded with alacrity to the President’s request. Governor Austin Blair protested when Michigan’s quota was set at only one regiment of 10 companies, explaining the state had enough willing manpower to do much more.

Michigan had to start almost from scratch. On paper it had 28 militia companies of 1,240 men, but they were poorly equipped and functioned more as social clubs than military formations. The only thing really military about them were names such as the Coldwater Cadets and the Detroit Light Guards. Abbott’s unit was the Burr Oak Guards. Since he was the postmaster of Burr Oak, he was the first one to see the governor’s proclamation about raising a regiment when it came through the mail.

For some reason Abbott doesn’t mention a grand ceremony that was held on May 11, 1861, when the regiment paraded to Campus Martius, an immense public square in the heart of the downtown area. Thousands turned out to view the spectacle, which included the presentation of the regimental colors. But the First Michigan was urgently needed to defend the nation’s capital, so two days later the regiment boarded the steamer May Queen to begin the first leg of their journey.

“At five o’clock,” Abbot later wrote, “the regiment by companies was marched on board, and by six all men in quarters for the trip to Cleveland. At seven the order was given to cast off the lines. The band played the Star Spangled Banner and hundreds of handkerchiefs was waved and the cheering goodbye was heard from those on board as we left the shore. The band on shore was playing ‘Columbia the Gem of the Ocean’ as we moved out upon the bosom of Lake Michigan. It was a beautiful sight—not a ripple on the lake and next morning at daylight we were ready to disembark (at Cleveland) and go aboard the (train) cars.”

The long train trip became almost a triumphal procession at each rail stop. They were cheered, fed well, and shown that Unionist sentiment was at a fever pitch. But there was one more hurdle before reaching their destination—Baltimore. Maryland was a slave state, and Baltimore a hotbed of secessionist feelings. There was a municipal ordinance that prohibited steam railroad tracks from being laid across the city. That meant that troops would have to leave their incoming train at President Station, and march 10 blocks to the Baltimore and Ohio’s Camden Station to catch another train and complete their journey.

A few weeks earlier the Sixth Massachusetts Militia regiment had been trying to peacefully make the transfer, only to be violently attacked by a secessionist mob while marching down Pratt Street. A full scale riot erupted, the mob pelting the soldiers with bricks, paving stones, and a scattering of pistol shots. The Ninth Massachusetts returned fire, and when it was over four soldiers and 12 civilians were dead.

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, was the First Michigan’s last stop before proceeding to Baltimore. The regiment was reviewed by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin, then preparations were made to depart for Baltimore. Abbott remembered “The train was ready and we went aboard. Here we were obliged to take freight cars, which some of the companies complained of, since the officers were furnished with a passenger car.

“The next morning we reached Baltimore and here another transfer. The regiment was to march through the city. Preparatory arms were traded and bayonets fixed. [We were ordered] if there was an attack by the mob to fire and charge bayonet. The regiment marched through the city in column by platoons. The sidewalks for a long distance on either side thronged with a rebels (sic) mob hurrahing for Jeff Davis but no violence was offered.”

The First Michigan arrived in Washington, D.C., on the evening of May 16, 1861. Abbott remembered it as “around six” but newspapers of the period report the time was more like 10 p.m. or even a little later. Washingtonians were awakened by the regimental band’s martial music, threw on clothes, and joined the growing crowds that cheered the new arrivals. They were not the first unit to arrive, but it was noted they were the first regiment from a “western” state.

The regiment was reviewed by President Lincoln, who earlier had supposedly exclaimed “Thank God for Michigan.” Regimental officers were invited to a White House reception, and though Lincoln was an unknown quantity at the time, Abbott and the others were charmed by the President’s humor, his down-to-earth friendliness and affability. Lincoln not only shook hands with each officer, he also pressed the flesh with each member of the regimental band that was providing music for the occasion.

The Battle of Bull Run was the first major clash of the Civil War, when both sides were still rank amateurs for the most part, their heads filled with dreams of romantic glory. The First Michigan did well for green troops, in part because they were led by Colonel Orlando Willcox, a West Pointer and professional soldier who was a veteran of the Seminole Wars and the Mexican-American conflict. He provided the firm hand and courageous example that steadied and inspired the men.

The regiment was positioned on the far right of the Federal line, and soon advanced down the right side of Sudley Road. The Confederates had just taken a Union battery, and the First Michigan’s mission was to try and retake it. They succeeded, and advanced to woods just south of the Henry House, where on Henry House Hill gray troops under General Thomas Jackson resisted all Union attempts to break their line. In fact it was their stubborn defense that gave Jackson his famous nickname of “Stonewall.”

By some accounts it was the First Michigan who had advanced the furthest into the Confederate position, though it was ultimately unsuccessful and came at a high cost. Willcox’s horse was shot from under him, and he was wounded and captured. For the First Michigan, as for the other untried Union forces, the day ended in confusion and humiliating defeat. Colonel Willcox and a large number of Michiganders were taken prisoner, and worse still, its regimental flag was also captured as a war trophy.

Captain Abbott doesn’t say much about the Bull Run debacle, but does mention that “the first man who fell was color sergeant (sic), struck by a shell which severed his head from his body.” That was Sergeant Calvin Colgrove, who was later remembered and honored. It was said that Captain Abbott helped rally the survivors and lead them back to Washington when the federal army retreated.

The defeat at Bull Run was a sobering experience, but everyone now realized the war was going to be a long and bloody one. The battered First Michigan returned home, their three-month enlistments at an end, but the regiment reformed as a new entity based on service for three years. The First Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment joined the newly formed Army of the Potomac, named after the river that flows past the nation’s capital.

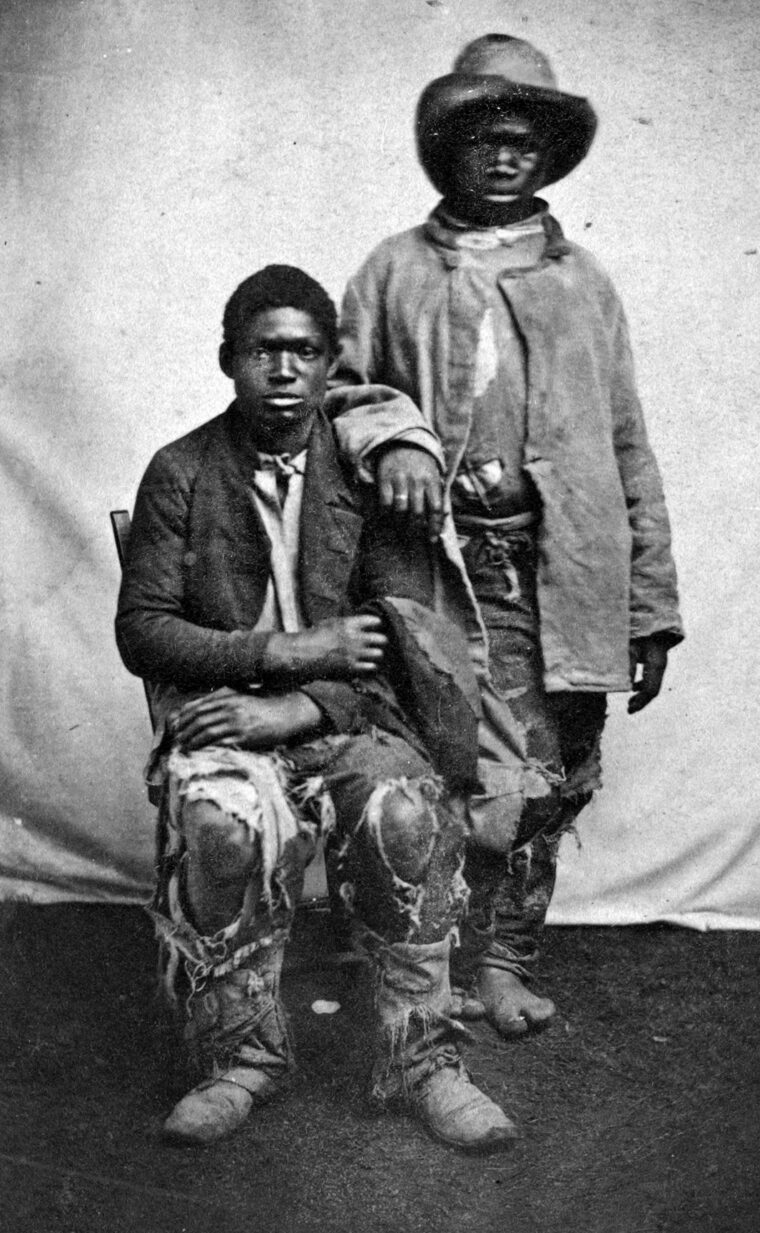

The fall of 1861 found the regiment guarding portions of the vital Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Confederate raiders were known to tear up tracks and generally sabotage the passage of Federal troops to and from Washington. Captain Abbott and his company were based at Contee’s Station, about 20 miles from the Capital. It was there that Abbott had to confront the issue of runaway slaves. This was early in the war, and the Lincoln administration’s main focus was on the restoration of the Union, not the emancipation of the south’s four million slaves.

There was a great fear—a valid one at the time—that if Lincoln moved too quickly against slavery, important slave border states like Kentucky that were still in the union might join the Confederacy. If that happened, the scales might be tipped and the south would win the war. For that reason, the Lincoln administration and the Union army were scrupulous about respecting “property rights,” even if the “property” consisted of human beings in bondage.

Abbott must have considered the incident as important, because in his diary he devotes several pages to the subject. He copies letters sent to him from the regimental colonel, his replies, and even a kind of deposition by a private involved in the case. It began when Corporal William H Radley recalled “The slave ‘Dick’ appeared at the camp at about 1 a.m. Tuesday standing several rods from the tents. One of the soldiers asked him if he were a slave and he said yes. He then came to the cook house when he was given something to eat…”

Radley goes on: “At about 11 a.m. I was ordered by Sergeant Hoffman to go with the slave Dick and bring his wife back to camp who he had said he had left a short distance behind him. After walking some time we came to the plantation of the slave owner. As we came in sight of the plantation I gave the man [the slave Dick] the musket [to defend himself] keeping the revolver for myself. As we were passing a mill on or near the plantation the man Duval, son of the [slave owner, Dr. Charles Duval] came running from the mill…saying ‘where are you going with that servant? He belongs to me’ I answered ‘You keep still if you know you are well off’ he then said ‘very well go on.’”

Radley then wrote, “we then went on to a tobacco field when we found this woman, his wife and four children. We then returned and as we repassed the mill the man who we spoke to before then asked what I was going to do with their servants [euphemism for slave] I answered that was my business.” Seeing both union soldier and slave armed, the younger Duvall changed his tune, saying “very well—they don’t belong to me.”

But Duval senior was upset, and went immediately to Union General Joseph Hooker to complain his “property” was taken away. Strictly following policy, Hooker gave Duval a letter ordering that said property would be returned immediately. Once he got the word, First Michigan Colonel John C. Robinson forwarded the missive to Captain Abbott to look into the matter and resolve any difficulties.

Dr. Duval did show up at Abbott’s camp one evening and saw that the slave and his family were there. Perhaps sensing that he was in unfriendly surroundings, Duval didn’t attempt to take possession but asked that they be held until morning. He—or a representative—would come by to pick them up and return them to slavery. Bound by official policy, Abbott had to agree to the arrangement.

But the next morning no one came. Duval’s reason for not coming or sending someone is not known, but the slave owner’s absence gave Abbott his opportunity. He immediately ordered the slaves to leave and advised them to “return home.” In other words, he was giving lip service to the official Union position at the time. Dick and his family were “given breakfast” and then “went away in the direction of Washington [D.C.]”

Depriving Dr. Duval of his human “property” might have had repercussions, so Abbott wrote the mitigating circumstances involved in the case. The man, his wife, and their children “were in a very destitute condition indeed having scarcely any clothing to cover their nakedness.” The white people of Maryland have been “kind” to Union soldiers in general, but the “condition of the colored man and his appeal for protection” was a major factor. Speaking of himself in the third person, Abbott concludes that “his sympathies were aroused to such an extent he permitted the occurrence as stated [giving aid to the escaped slaves]. The young man Duval is no doubt a hard master as I have it from reliable men and the same impressions had been communicated to that detachment [Radley and others].”

An anonymous adage usually attributed to the Great War described a soldier’s life as “months of boredom punctuated by minutes of sheer terror.” That was no less true for Abbott, who in his diary at times confesses that there was little or nothing to record that day. Sometimes, seemingly to fill a page, he details when they had breakfast, or how he set up the various guard duty assignments as Officer of the Day.

The fall and early winter of 1861-62 was one such comparatively tedious stretch. In February, 1862 Abbott noted that “private William Smith of Company B having absented himself without leave has had a charge of desertion preferred against him. February 17th Private Smith was tried by court martial and sentenced to “30 days imprisonment with a 32 pound ball and chain attached to his leg. It was thought by the court that he was not guilty of intention to desert and was punished for being absent without leave.”

Abbott often speaks in the third person, as when he notes “Jan 10 (sic) Capt Abbott received a furlough for 10 days and started for Michigan—did not return until the 28th having been delayed in getting transportation for detachment (sic) of men he recruited during his absence.” He further noted that two of the recruits, Leonard Whitmayer and George Bandmaster, were well known to him, having been “Members of Capt Abbott’s Comp (sic) G in the three months service.”

In early 1862, General George B. McClelland was commander of the Army of the Potomac. Idolized by his men, who gave him the affectionate sobriquet of “Little Mac,” McClelland was a masterful organizer and trainer, transforming the Army of the Potomac into a fighting force of real merit. Unfortunately, events were to show he had serious flaws as a general in the field. He was timid, overcautious, and slow in maneuver.

Above all, he seemed to lack the moral courage required from a successful battlefield general. A commander should not spend his men’s lives recklessly, but should also have the courage to send them into harm’s way to achieve victory. McClellan seemed to lack that quality, delaying action for weeks while sending Lincoln pleas for reinforcements, coupled with a barrage of excuses for his inactivity.

In the spring of 1862 McClelland finally launched what became known as the “Peninsula Campaign.” His main objective was the capture of Richmond, the Confederate capital. Using the Union’s advantage in sea power, McClellan was going to transport the army down the Chesapeake Bay to Fort Monroe at the tip of a peninsula formed by the York and James Rivers.

By going up the peninsula, the Army of the Potomac would only have two rivers to cross, and its base at Fort Monroe would be only about 75 miles from Richmond. As part of the Army of the Potomac’s Fifth Corps, the First Michigan would take active part in the campaign. Unfortunately Abbott contracted typhoid fever, and ended up in a Fort Monroe hospital for 20 days. Even after he was officially released, the Michigander admitted he “wasn’t able to walk without a cane, or draw his sword from the scabbard with his right hand.”

Nevertheless, Abbott reported for duty June 27,1862, just in time to participate in the Battle of Gaines Mill. The Union’s peninsula offensive had slowed to a crawl, sputtering out just as it neared the Confederate capital. General Fitz John Porter, the Fifth Corps commander at the time, placed his men in a very strong defensive position along a meandering, boggy stream called Boatswain’s Creek. Its banks were a virtual swamp, carpeted with thick undergrowth and clumps of trees.

The position stretched almost two miles, with Boatswain’s Creek forming a kind of natural moat that gave added protection. General John Morell’s First Division, which included Abbot’s regiment, anchored the left flank of the Fifth Corps defenses. The battle was noted for being the debut of General Robert E Lee and his newly named Army of Northern Virginia. Abbott describes his position as being along a “deep ravine.” This is probably the start of the swampy bottomland that edged Boatswain’s Creek.

Abbott tells us that “I was ordered to take charge of the left and construct an abattis in front of our lines.” Generally, that means felled trees with sharpened ends facing toward the enemy. “At one o’clock,” he continues, “the heavy guns of the enemy began to thunder, and occasionally a shell would explode near our line. They were replied promptly by our 32 pounder(s) planted on our right and the rear of our line the [Union] shots passing over our heads.” He’s most likely referring to the supporting batteries of the 1st Rhode Island light Artillery as well as U.S Artillery and Pennsylvania Artillery which were on the slopes of Turkey Hill, a plateau that gave them an excellent view and field of fire.

Abbott then writes, “At three o’clock Copys B (sic), Capt. Byrnes (my old co), detached from the Regt and sent to the front as skirmishers. Having been out a short time they fell back before the advance of the main line of enemy infantry.” These were General A.P. Hill’s Light Division, composed of Georgians, North Carolinians, and Alabamans. Hill’s force of some 12,000 men had to cross a quarter-mile of open ground, only to face new obstacles as they confronted the viscous, swampy muck that edged the meandering Boatswain’s Creek.

Major Abbott and his men were veterans by this point, but the spectacle of long lines of gray-clad infantry advancing in almost parade ground fashion still was a thing to be admired. As Abbott commented, “The enemy advancing over the ridge and down the opposite side of the ravine in splendid style until within twenty rods of our line when a heavy fire was opened along our front causing many a gray coat to fall to the ground.” The Confederates facing Abbott’s position were probably Georgians, possibly the 35th Georgia, but all of the “rebels” showed exemplary courage.

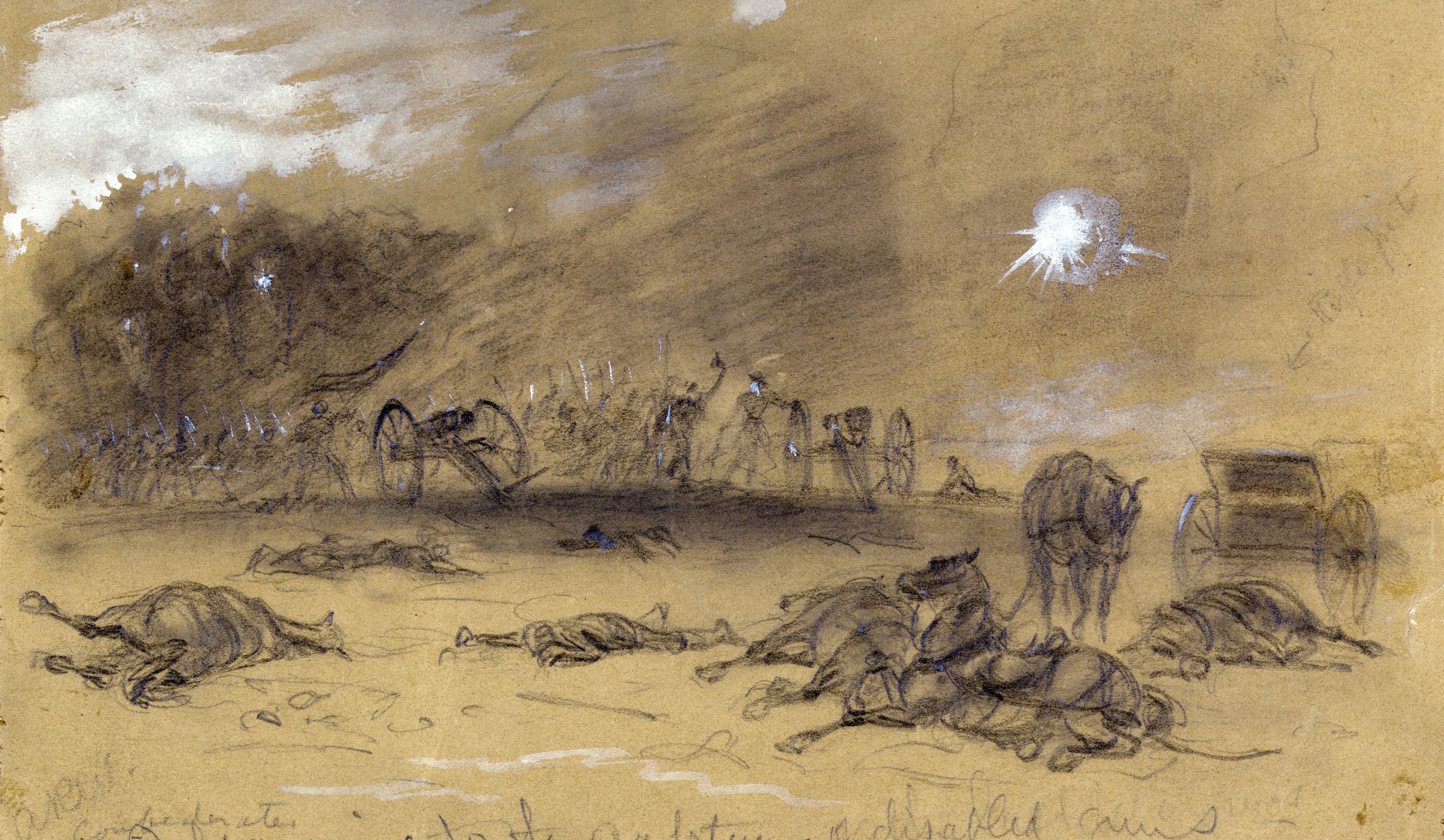

or dead. I can never forget that night…”

The attacks continued, and Abbott goes on, “By an order of Col [Horace] Roberts (who replaced Robinson as commander of the 1st Michigan at the time) our fire was reserved until the enemy had advanced to short musket range when the dogs of war infantry and artillery were let loose and they were again driven back with hearty loss.” The battle seesawed back and forth, but when all of his men had finally come up and were in position Lee gave an order for a general advance.

This was the largest confederate offensive in the war, with no less than 32,000 men—16 brigades—attacking along a broad front. Even the celebrated “Pickett’s charge” involved far fewer soldiers. Porter’s Fifth Corps had performed prodigies of valor throughout a long, bloody, and exhausting day, but the greatly outnumbered Yankees finally gave way. It was nearing sunset, and the gathering darkness combined with the dense clouds of lingering gun smoke to produce chaos and confusion.

Abbott was focused on the First Michigan’s Company F, and in the confusion didn’t realize that the whole Union front had collapsed and individual units were in headlong retreat. Abbott writes, “This was the most desperate fighting of any during the day—here our men and officers fell like sheep before the slaughter…Individual [Union] regiments contested the ground and only gave way to an overwhelming force. The First Mich (sic) being on the extreme left was the last to give way.”

Major Abbott quickly gave orders to Company F to withdraw, but he was dismounted and didn’t know where his mount could be found. He was still very lame from his previous illness, and found to his chagrin he couldn’t keep up with the departing troops. The Confederates were surging forward, and in the process were taking many prisoners. Abbott’s death or capture seemed likely, so he decided to pause a moment to figure out his next moves.

“I took shelter in a ravine immediately on the left which was filled with underbrush. As luck would have it I found in the ravine a horse which was hitched to a tree and afterwards I found to belong to the Major of the 12th N.(sic) York Infantry.” Thus he was able to save “myself and the horse from the hands of the enemy.”

Colonel Roberts was killed at Second Bull Run. A replacement was already chosen, but was unable to take the post because he was incapacitated by a wound he sustained at Gaines Mill. Abbott, by now a lieutenant colonel, replaced him and became Colonel of the First Michigan. This was the late summer of 1862. The Battle of Antietam followed, and in December of that same year Lee defeated the Army of the Potomac at Fredericksburg.

Even by Civil War standards Fredericksburg was a terrible slaughter, with the lion’s share of the casualties from the Army of the Potomac. Abbott, twice wounded, recalled “Oh, the horrors of war, of a battle like this! Thousands of wounded, dying or dead. I can never forget that night—such horrible groans and cries—no pen can describe, or pencil paint them.”

After Fredericksburg came Chancellorsville, considered Lee’s greatest victory, and then, finally, the dramatic confrontation at Gettysburg. The march to Gettysburg had its own attendant horrors, including forced marching under a broiling sun. Scores of his men were laid low by sunstroke and at least one man died of it. Many others fell out from sheer exhaustion, though they rejoined the regiment by evening. At one point Abbott estimated they had marched over 30 miles in one day.

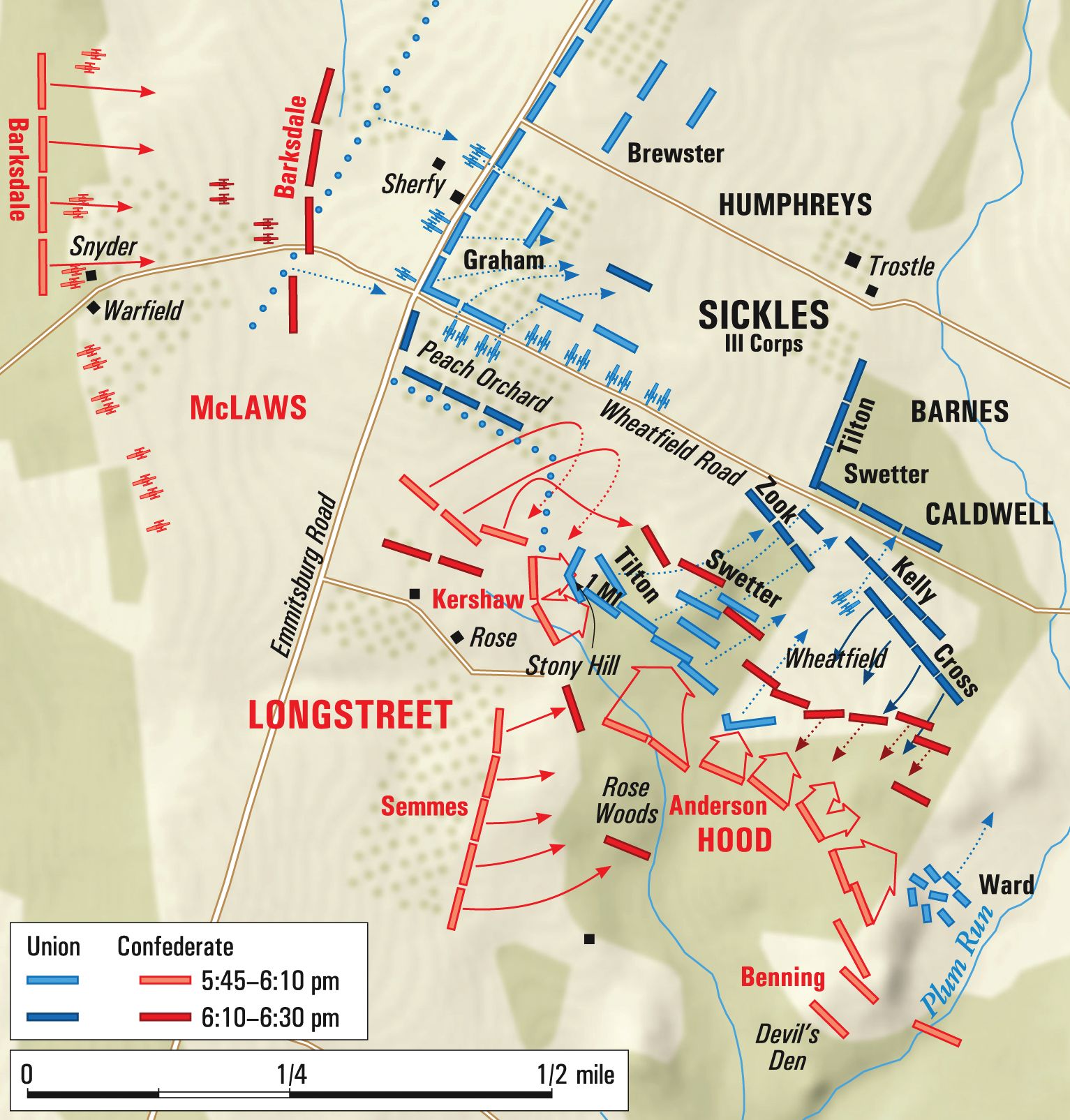

Once his men were in position at Stony Hill, Abbott took stock of the situation. Looking down from the Stony Hill’s modest elevation, he could see farmland, verdant and green as it simmered in the torrid summer sum. A few hundred yards behind him stalks of summer wheat gently swayed with every small breeze. The First Michigan was part of General William Tilton’s brigade, and four other brigade regiments soon took their respective positions. The 118th Pennsylvania anchored the right, the First Michigan the center, and the 18th Massachusetts on the left. The 22nd Massachusetts was positioned just behind as a reserve.

General Lee’s plan was to attack the Federal left, and if successful, the gray troops would continue the advance with a strong flanking assault that might roll up the whole Union line. Tilton’s Brigade was one of the units assigned to prevent such a catastrophe. The First Michigan would be facing men of General George T. Anderson’s brigade, part of General James Longstreet’s First Corps, Army of Northern Virginia.

Abbott knew the brigade was going to face a major onslaught, and the main attack would be preceded by a swarm of skirmishing sharpshooters. The Colonel recalled, “I immediately gave orders for my men to lay down and not after a few minutes a stray shot from the enemy Sharp Shooters (sic) came over…. I order men to their feet, load and fix bayonets and lay down again with positive instruction not to fire until orders were given. [It] was my intention to wait until the enemy was well within short musket range and make every shot [count].”

The attacking Confederates drew nearer, and “we did not wait long when the well known rebel yell was heard in our immediate front…. They came down on us with banners flying…. The enemy had commenced firing as it advanced now plainly in view with two lines of battle.” Those two gray and butternut lines were the men of the 8th and 9th Georgia regiments. “The regt (sic) to my right and left commenced firing but my own (men) remained anxiously waiting for the word of command.”

“Our Captain Griffith Co E getting a little nervous as they came along said ‘what is the matter with the col [colonel]? Why in HC [hell?] don’t he begin to fire?’ Then, the crisis of this local fight: the 118th Pennsylvania seemed to have given way and “it looked as though it would be hard to hold our line but I knew my men could be trusted.”

Abbott didn’t know it, but the 118 had actually been ordered to fall back by Brigade commander Tilton, subsequently a much debated move. The 118th didn’t want to leave, crying “no retreat! no retreat! This is our (home) ground!” but orders were orders and they reluctantly withdrew. But that meant the First Michigan would potentially be faced with Confederates both in front and the right flank.

But Abbott had a contingency plan in place that would address this threat. The regiment would deploy in a kind of upside down “L” formation, with the smaller stroke of the letter facing the right. As Abbott remembered: “…when the (gray) lines were 10 rods off our front the words “attention Battalion” every man was on his feet perfectly cool and at the command fire by files—commence firing! it was repeated all along down our lines and our fire was continuous.”

Abbot continues, “the enemy was so badly crippled that their lines began to waver (and) finally halted.” The flanking effort stalled, and finally the gray coats “fell back in confusion and the ground was ours.” As a grim postscript, Abbott remembered “when our firing commenced they were so close that every shot told and the ground was strewn with their dead, dying, and wounded.” The Confederates would return, and the First Michigan would be withdrawn with the rest of Tilton’s battalion, but after seesaw fighting the Union regained control of the ground.

Colonel Abbott was badly wounded shortly after Anderson’s initial attack. He describes the incident in a somewhat laconic manner, merely recording “I received a wound in my face, the ball passing under my nose nearing severing my upper lip and completely demolishing my teeth.” With his face swelling and bloody, his mouth a disaster of deep cuts and shattered teeth, Abbott was forced to relinquish command.

“After being wounded,” he continues, “turned over the regiment to Lt Colonel Thorp [and] went to the rear and had my lip stitched on by a surgeon of the Fifth New York regiment. After having my wound dressed I decided to go direct to Fifth Corps Hospital.” After walking a bit, he saw a series of horse-drawn ambulances and hitched a ride on one, taking a “seat by the driver.”

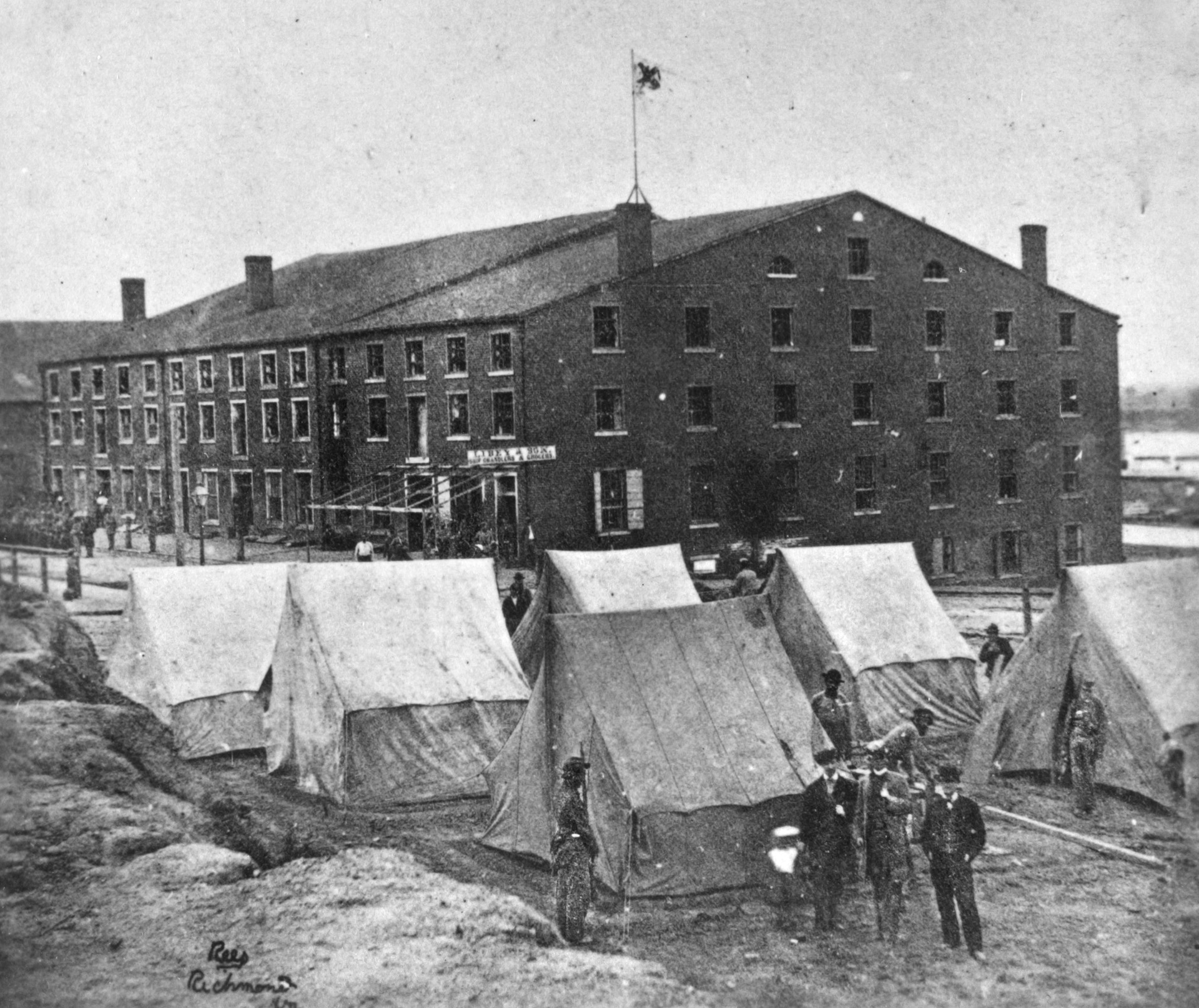

It wasn’t a long journey and they soon arrived at the makeshift hospital, “a farm house and barn near which was a large apple orchard. The barn was occupied as a hospital.” This was the Weikert house and barn. After a huge Confederate bombardment on July 3, the hospital was moved to the Bushman farm. Abbott was a self-reliant sort, so when he saw some new hay he gathered some to make a bed and spread the armful under one of the apple trees.

Settling down, he “laid down to rest where I remained until the next morning.” The wounded Colonel met some of his own men from the First Michigan, who perhaps were looking for him, because they had a stretcher. Admittedly “weak and tired,” and no doubt in pain, Abbott allowed himself to be carried to the new Corps hospital at the Bushman farm. He was given quarters in a tent with another presumably wounded officer.

This was July 3, the day of Pickett’s charge, a celebrated event that was preceded by what was probably the greatest artillery duel of the entire war. The Confederates alone had somewhere between 150 and 170 guns. Abbott recalled that July 3 was “the most desperate day of battle. The earth fairly trembled from the effects of artillery and the musketry was continuous from early morning till night when it began to die away.”

Sitting there in his hospital tent, he had time to reflect on the momentous events that had just taken place. A great battle had been fought for three long days,” he wrote. “General Meade, had won the day and the turning point in one of the greatest wars of the nineteenth century had been reached. Gettysburg was ours at dreadful cost.”

Gettysburg also proved to be Abbott’s last experience as an active duty soldier. He was sent to Washington, D.C., to take part in court martial tribunals. Though his facial wound healed, he was beset by ill health, and he never again went on campaign, though his regiment fought on all the way to Appomattox. Colonel Ira Abbott did manage to join the First Michigan in the grand victory parade that was held in Washington in May of 1865. He also became a brevet (honorary) brigadier general for his “meritorious services” during the war.

After the war Abbott obtained a position as a clerk in the Pensioner’s office in Washington, a job he kept, incredibly, the rest of his life, even into his eighties. General Ira Coray Abbott was active in veteran’s affairs and regimental reunions until his death in 1908 at the age of 83.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments