By Richard Baker

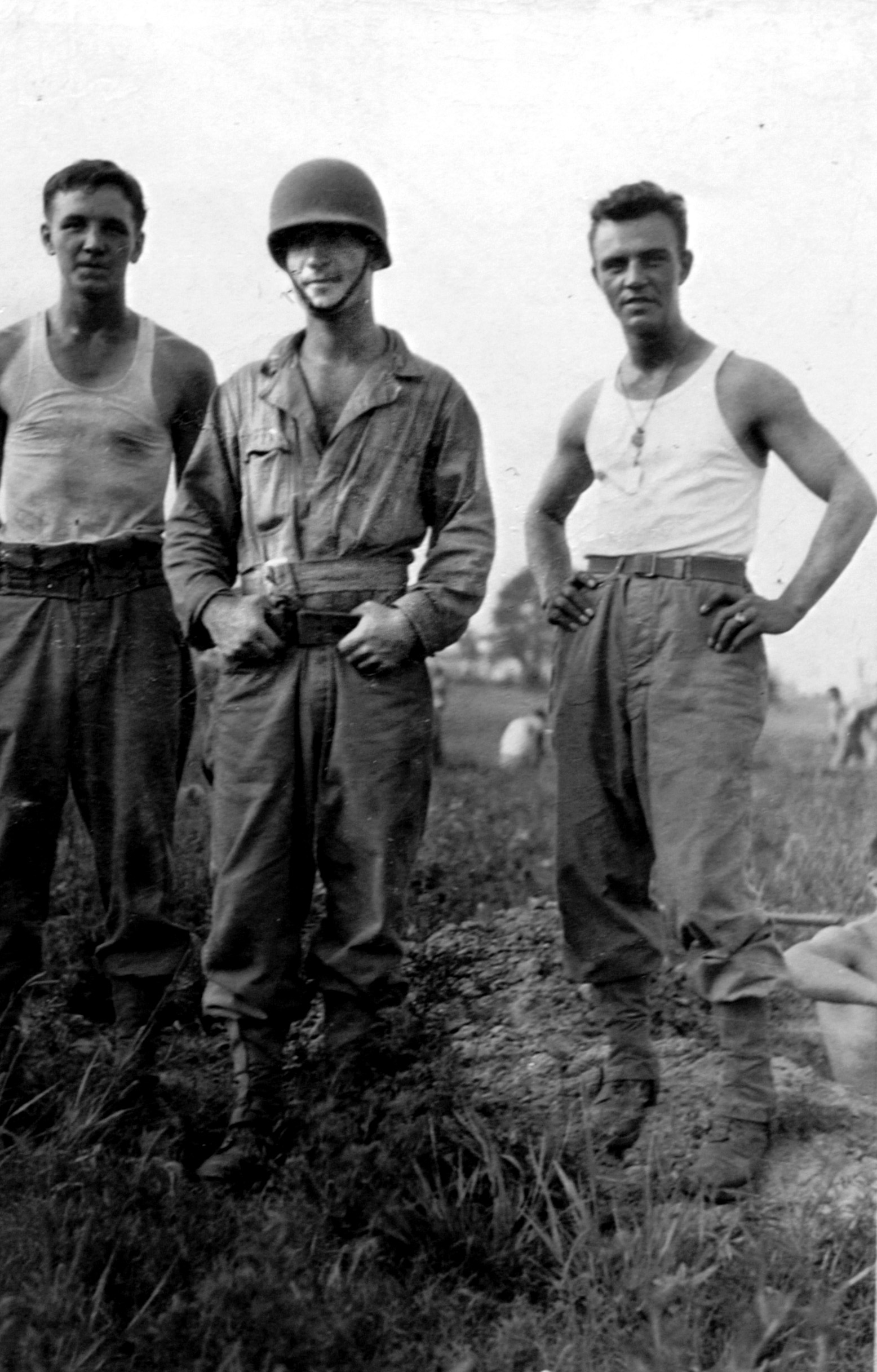

When a friend from Wolsey, South Dakota, asked Alven Baker why he was joining the army in 1941 and not another branch of the service, he replied, “To capture Adolf Hitler.” Little did he realize he would get that chance.

Baker’s road to Berchtesgaden started with the 290th Combat Engineers at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, and took him to France in November 1944, then to Tiverton, in Devonshire, England, then back to France before fighting halfway across Europe and arriving in Berchtesgaden on May 4, 1945.

By the time Captain Baker reached the Fuhrer’s mountain retreat, no one seemed to know where Adolf Hitler was. The war in Europe was almost finished. Rumors indicated that he was holed up in his bunker in Berlin, but such reports remained unconfirmed. He had made only two official public appearances since the German defeat at Stalingrad in early 1943.

Hitler had assured the German people of victory at Stalingrad when he ordered General (later Field Marshal) Friedrich Paulus to launch his attack with the 330,000 men of the Sixth Army, on August 19, 1942. By February 2, the remaining 90,000 German soldiers had laid down their arms. Many had died from the cold and starvation.

After this humiliating defeat, Hitler preferred keeping a low profile, a far cry from the days when he had welcomed the accolades of his adoring public.

If he was not in his bunker in Berlin, where was he? The Berghof, his home at Berchtesgaden and a favorite retreat, seemed a likely spot. During the war, Hitler had spent more time there than any other place except Wolfsschanze, known as the Wolf’s Lair, near Rastenburg in East Prussia. Many retreating German forces were moving into the Bavarian Alps, perhaps for a last stand or to protect their Fuhrer.

Hitler developed his love for Berchtesgaden during the 1920s after his release from prison. He needed a quiet place for inspiration and to finish his book Mein Kampf. This small resort town in the Bavarian Alps, surrounded by Austria, provided the ideal spot for him to work. Here his mind pondered the deeds of great German legends as he looked deeply into the soul of the German people and looked for ways to manipulate them.

Hitler rented a small chalet from a businessman named Otto Winter before buying the house in 1933, using the royalties he had earned from his book. Over the years, using his architectural plans, workers expanded the house, giving the main rooms a light and airy feel. A large picture window was installed and provided much of the interior light of the main room. Hitler took pride in furnishing the chalet using mostly antique German pieces.

Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler’s favorite photographer, and guests took many pictures of him and his visitors as they relaxed high in the mountains and plotted the invasions and enslavement of other countries and peoples. Hitler is often seen laughing with his mistress, Eva Braun, or petting his dog, Blondi. Regular guests included Albert Speer, chief architect and Minister of Armaments; Joseph Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda; Reinhard Heydrich, Chief of the Reich Main Security office—including the Gestapo—and Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS.

The invasion of Russia was discussed with top military advisers at the Berghof, including members of the Chiefs of Armed Forces High Command, Army High Command, and the Navy High Command, during the Berghof Conference in July 1940. Hitler was convinced that an invasion to the East would cause Britain to sue for peace or that the United States would stop its support. Notes from General Franz Halder, Chief of Staff of the Army High Command, recorded Hitler’s general plans: “With Russia smashed, Britain’s last hope would be shattered. Germany will then be master of Europe and the Balkans. Decision: Russia’s destruction must therefore be made part of this struggle.”

The area continued to expand over the years. The Kehlsteinhaus, known as the “Eagle’s Nest,” was commissioned by Martin Bormann, Hitler’s secretary, completed in 1939, and presented to Hitler for his 50th birthday. Workers built a road up the side of the mountain, but the last 400 feet to the house was reached through a large and elaborate elevator. Laborers drove the elevator shaft straight through granite in a marvelous feat of engineering.

The area became known as the Obersalzberg complex and eventually contained about 80 buildings, including barracks for several SS. units. Obersturmbannfuhrer Bernhard Fran was put in command of a contingent of the SS Leibstandarte to protect Hitler. As the war continued, Hitler needed that protection.

Captain Eberhard von Breitenbuch, a reserve cavalry officer with Army Group Center, disillusioned by the war, arrived on March 11, 1944, intent on killing the Fuhrer. Carrying a Browning automatic pistol in his pocket, he arrived at the Berghof as aide-de-camp to Field Marshal Ernst Busch, who had come for a meeting. Hitler was known for his luck, and it held when Breitenbuch arrived. The Fuhrer had issued a directive that morning that no aides were to be admitted into the meeting. Guards refused to let Breitenbuch into the room.

General Henning von Tresckow had recruited Breitenbuch into the conspiracy. Tresckow was extremely well read, spoke several languages, and was a world traveler. Once loyal to Hitler, Tresckow had become disillusioned with the Nazi Party, especially after “Kristallnacht,” the nationwide pogrom against the Jews on November 9, 1938, when businesses were destroyed and the Jewish people persecuted. He viewed the act as a degradation of civilization.

Later, Nazi atrocities committed in the East, especially the murder of thousands of Jews at Borisov, increased Tresckow’s determination to assassinate Hitler. He recruited many German officers into his organization, including Major Carl-Hans Graf von Hardenberg, Lieutenant Colonel Georg Schulze-Buttger, and Colonel Rudolf Christoph Freiherr von Gersdorff. Several attempted assassinations against Hitler had all failed. The closest he came to success was with Operation Valkyire, when Colonel Claus von Stauffenburg placed a bomb under the conference table in Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair. Although the bomb exploded, Hitler suffered only minor wounds.

By 1945, the Allies had everything they needed to capture Hitler in Berlin. The Russians were tearing down the gates of the city, with the Americans, British and French waiting, should he attempt an escape to the west. If he was in Berchtesgaden, they needed a secret weapon; they needed Captain Alven Baker from Wolsey, South Dakota.

Alven Baker was a simple farm boy who lived with his parents. A slight young man, he helped his father, Loren, grow flax and thresh various grains, using his Rumely Oil Pull tractor. Baker loved starting the tractor by jumping on the rungs of the flywheel until the engine fired. The tractor ran on kerosene and was always temperamental; Alven learned his engineering skills early on by attempting to keep the tractor running. Baker’s brother, Wesley, had already joined the cavalry before the outbreak of war. Wesley, a championship clarinet player, soon joined the National Guard.

Alven’s leadership ability was recognized almost immediately, and he was sent to Officer Candidate School at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, where he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Combat Engineers. He quickly rose to the rank of captain and was assigned Commander of Company B, 290th Combat Engineers, at Camp Shelby. His journey on the road to capturing Adolf Hitler had begun.

After further training with the engineers, the battalion shipped out for England in 1944. With the exception of Baker’s B Company, which landed at Cherbourg, the remaining companies arrived in Southampton in early November. After the uneventful stop in France, B Company was quickly shipped to England to join the rest of the battalion, now stationed at Tiverton, 15 miles from Exeter. The engineers endeared themselves to the local population by helping rebuild many of the bombed-out buildings in London. They also built new housing for families who had lost their homes. During the construction operations, the engineers often lived in tents near the projects to prepare them for the rigors of rough living in combat situations yet to come.

For two months, the engineers learned to erect floating and fixed Bailey Bridges of different lengths and over various obstacles. Baker loved the work and found the challenges of engineering exhilarating. Every project was a new challenge. When he learned to erect the bridges, he pushed his men to build them faster—a skill that paid later dividends.

The joys of England become a memory when, on December 31, 1944, the battalion boarded the liberty ship HMS Empire Rapier for the short trip to Le Havre, France. They moved 200 miles inland to Orbey, Alsace. All engineering was forgotten, and the battalion became riflemen for the next 21 days. They were first assigned to the 3rd Infantry Division, then as infantry to the 112th Regiment of the 28th Infantry Division, fighting in the Vosges Mountains against German General Siegfried Rasp’s 19th Army under Heinrich Himmler’s Army Group Upper Rhine.

The American units had replaced the tired and battered 36th Infantry Division and were in a position to support General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny’s French First Army, which had been assigned to reduce the Colmar Pocket.

The 36th Infantry Division had been badly mauled in Italy. In an effort to divert the Germans from the landings at Anzio, they’d launched an unsuccessful diversionary attack to cross the Rapido River and lost the better part of two of their three regiments. The division absorbed replacements and then went into the line in France. By the end of the war, it was pounding against the Siegfried Line on the German frontier. The 36th Division has served 400 days in combat, suffered the ninth- highest casualty rate of any U.S. Army Division of the war, and accepted the surrender of Field Marshal Herman Goering.

The Germans considered the area around the town of Colmar, in Alsace, France, as German soil and were fiercely defending it. The duty was brutal, not just because of the continuous blizzards and freezing temperatures of one of the coldest winters on record, but also because of the horrendous combat. Day and night the engineers organized patrols through the German lines, suffering their greatest casualties.

On January 23, 1945, Captain Baker was ordered to send a joint reconnaissance patrol with Company A into German lines to determine the exact enemy positions. Lieutenant McDermott was chosen to lead a platoon from Company A. Captain Baker chose his best lieutenant, Alan Hunnicutt, to lead the platoon from Company B.

After A Company advanced just 200 yards, the Germans opened fire and pinned them down. Bullets chipped away at the dirt as McDermott and his men dug in. Company B advanced over 800 yards before being hit with machine-gun fire, mortars, and small arms. All communications were severed. Both companies were stuck, unable to advance or to retreat without drawing more fire. There was little to be done except stay low and wait.

Lieutenant Hunnicutt and 10 of his men had become separated from the rest of the platoon. His remaining men assumed they had been killed. The battalion commander was ordered to withdraw the patrols and sent out runners to bring them back. Many of the men had been killed instantly, while several of the wounded returned to the line with the help of stretcher-bearers. Although wounded, Lieutenant McDermott managed to get his men back to safety. Lieutenant Hunnicutt and his men were reported as “Missing in Action.”

Life did not get any easier for Captain Baker and B Company. A week later, 2nd Platoon came under a fierce mortar attack that set fire to the command post. Lieutenant Edward Armani, the platoon leader, moved to the safety of a nearby farm building. Looking for the safest place in the building, he moved his command post to the basement. In one of many unexplainable events of war, a mortar shell landed outside on the ice and bounced through an opening into the basement, where it hit the wall, exploded, and killed the lieutenant and his aide.

Two days later, Lieutenant Walter Gentry was shot through the head and killed while on patrol. His men refused to leave his body in the field and managed to return it to the American lines.

Colonel G. M. Nelson, commander of the 112th Infantry Regiment, stated: “During the period 17 January 1945 to 5 February 1945 the 290th Combat Engineer Brigade performed the duty of front-line infantry without special training and had no opportunity to perform its normal engineering functions. While employed as infantry they occupied front-line positions in direct contact with the enemy and under direct enemy observation, artillery, mortar and small-arms fire. Despite their lack of training for this kind of combat, they exhibited remarkable qualities of courage and coolness in the face of the enemy and under severe winter conditions which existed on the high mountain positions.”

The battalion was soon pulled out of the line. If Baker thought, however, that life was going to get any easier, he was mistaken.

Combat engineers are an interesting and often unsung lot. Before any units can move, the combat engineers must often build roads and bridges on which to travel. Enemy roads and fields must be cleared of mines, booby traps removed from buildings and obstacles, bunkers and gun emplacements built, and command posts established. Without the Combat Engineers, the army cannot move efficiently. The engineers were often under direct enemy fire.

The engineers were finally assigned to their regular mission and were ordered to maintain the main supply route between St. Marie Aux Mines and St. Die. The duty seemed like a holiday compared to what they had experienced in the mountains fighting as infantry. The work was difficult; melting snow and mudslides were not uncommon. Each day, Captain Baker moved closer to his destiny with Hitler.

The battalion was soon on the move across France, building bridges, repairing roads and clearing minefields. Before the war was over, they had completed over 40 bridges. Again, they were within 200 yards of the German lines at Weingarten, where they captured two German officers, discovered several German trenches with machine-gun emplacements, found many stores of ammunition, and opened all the roads in the area by clearing highways of dead animals, wrecked tanks, trucks, cars, wagons, and various road blocks. They also guarded several downed bombers and cleared houses of booby traps.

The speed at which they moved was remarkable. In a single month, while advancing from Mannheim to Murnau, their command post moved 21 times. Along the way they suppressed a warehouse riot by civilians in Weinheim until the military police could arrive. In Allersheim they showed their speed and effectiveness. Assigned to the 4th Infantry Division, they started to build a class 40 bridge over the river. A class 40 bridge is a more permanent and stable structure anchored into the ground, usually with concrete, and it was time-consuming to build. Orders were received that a combat unit was in deep trouble on the other side and they desperately needed tank support. The engineers dropped work on the fixed bridge and set a record for building an M-2 floating bridge.

German prisoners, along with freed American prisoners, started flowing through the Allied lines. Lieutenant Hunnicutt and the soldiers who had vanished in the Vosges Mountains were among them. They had been captured shortly after separating from the patrol. No one was happier to see them than Captain Baker.

The 12th Armored Division was ordered to launch an attack across the Loisach River. They first needed to get the 36th Infantry Division across to establish a bridgehead so the engineers could span the river for the tanks. Captain Alven Baker and B Company were given the task of supporting the operation. He planned it carefully, not just gathering all the needed boats but also stockpiling the equipment for the Bailey bridge. At dawn, his men ferried the entire 36th Infantry over the river, catching the enemy completely by surprise. Not a single shot was fired. By 1 p.m., Company B had completed the 150-foot bridge. For his command in this operation, Baker was awarded the Bronze Star.

Fate now took Baker in hand. After being ordered to sweep the area around the city of Bichl, B Company was ordered to support the 2nd French Armored Division of the First French Army. They were old friends and had fought together in the Vosges Mountains. The French had few engineers and often needed the assistance of the British and Americans.

The war was winding down quickly, and only mopping-up operations remained. Everywhere the Germans were surrendering. Capturing Hitler became a priority. Egos came into play as generals, thinking the Fuehrer might be there, plotted to get to Berchtesgaden first. If Hitler was not there, they all wanted the credit of at least taking his prize town, the tranquil scene of so much underlying evil. The French 2nd Armored Division was in perfect position for the assault. Troops of the 3rd Infantry Division and the 101st Airborne Division were also nearby.

The 2nd French Armored Division, with Captain Baker and B Company of the 290th Combat Engineers attached, rolled unopposed into Berchtesgaden first. Baker had never seen such a beautiful place. He did not linger to take in the sights. The French seemed to be confused and remained inactive. Baker had a mission to complete. He left Lieutenant Leo Barber in charge of the company and, along with a corporal, headed for the Eagle’s Nest on a little “scouting” mission. Baker did not want to take a large force up the mountain, drawing attention to himself, or get caught disobeying orders. His entire body tingled at the thought of capturing Hitler.

Years later Baker said, “I figured I could take him by surprise. After all, it was just me against him and all his personal SS guards. The last thing Hitler would expect would be an attack by a South Dakota farm boy.”

The Eagle’s Nest sat high on a mountain ledge. At the base of a sheer cliff they discovered the large elevator shaft dug into the mountainside. The elevator moved men, equipment, and supplies to Eagle’s Nest and was stopped halfway up the shaft. There was no other way to get to the building except straight up the rock wall. There are few mountains on the plains of South Dakota, but the captain and the corporal proceeded to climb the rock wall anyway. The climb was treacherous. Fortunately, a high bank of snow remained at the foot of the mountain, so the climb was shorter than anticipated.

The Eagle’s Nest was deserted. They searched everywhere, through every room and closet, anticipating an ambush at any moment by SS guards. They sat at a large conference table and decided their next move. Although Hitler was not there, they wanted to prove that they had arrived first and had at least made the attempt to capture him. Baker wanted something totally unique as proof. He knew they needed to work fast, since soon the place would be overwhelmed with officers claiming to be the first to arrive. As they gathered souvenirs, Baker continued to look for something unique.

All Hitler’s personal items were marked with his initials, and they went for those first, including beautiful monogrammed wine glasses etched with A.H. astride a German Eagle and Swastika, and the pillow case from Hitler’s bed, his initials sewn into the cloth. These were interesting, but any soldier that entered later would find similar things. Next, Baker found the rug from Eva Braun’s room. As Hitler’s mistress, she maintained her own room. There was only one rug in the room, so it was not only unique, but would come in handy for protecting the glasses.

Baker thought the candle holders might have been built just for the house, so he grabbed one of them. Then he thought of the large tablecloth on the conference table. It was intricately hand woven and quite beautiful, but much too large to carry. He took his bayonet and cut off the end to wrap around the glasses that would be placed in the rug.

Unable to find anything more unique, they started collecting various objects of interest. He found a Luger pistol and Nazi armband in Hitler’s bedroom and gathered up some keys that fit the doors. In another room he found a cheap reproduction painting of Hitler looking stern and defiant.

Together, Baker and the corporal rolled everything together and tied the bundle into the rug. They stopped for a rest. Baker, not knowing that Hitler had already committed suicide in Berlin, was still convinced he was in the area. “I couldn’t admit defeat,” he said. He discussed the situation with the corporal. Then it hit him. Hitler was hiding in the elevator. Why else would the elevator be midway up the shaft? He found an ax and told the corporal to watch the loot. He was about to capture the world’s worst tyrant.

Baker climbed down the shaft and onto the roof of the elevator. He chopped through the roof and dropped inside the empty elevator. Only then did Baker realize that going after Hitler was a “damned stupid idea. If he had been there he would have been protected by SS guards waiting to kill me.”

Baker stood in one of the most beautiful elevators in the world, all green leather and polished brass. Still breathless, he looked around as he thought about his next move. Then it hit him. Facing him was the object he had been seeking, the brass elevator panel. The panel glowed like a precious jewel. He knew it was totally unique and made strictly for Hitler’s personal elevator. Not another one in the world existed. With his bayonet he unscrewed the panel and held it in his hands like a gold ingot. They say that to the victor belong the spoils. To Baker, the spoils belonged to him and his glory.

Baker tied the heavy brass object around his neck using the lace from his combat boot. With great difficulty he climbed back up out of the shaft, the panel dangling from around his neck. By then several Frenchmen had made their way into the Eagle’s Nest and were gathering up armloads of Hitler’s personal belongings and tossing them down the sides of the mountain to the cries of “Vive la France!”

The corporal had found a bottle of wine, and they sat at the conference table and enjoyed a drink. “I had been ready to capture Adolf Hitler. What a disappointment not to find him.”

Baker and the corporal gathered up their rug full of goods and tossed the bundle over the side of the mountain because it was too heavy and awkward to carry. They needed to keep the souvenirs away from the French. That any of the wine glasses survived the fall was simply luck.

Baker returned to Berchtesgaden only to find that a soldier had discovered Hitler’s Mercedes hidden in town. The car had an inch of armor plating on the floor, and the engine was plated with chrome. The doors and windows were bulletproof, the seats covered with fine leather. Baker reminded the soldier that all confiscated German vehicles must be turned over to the military authorities. He then managed to ship the car as far as England, where it was discovered and acquired by another officer and later sold in the United States.

Undaunted by his recent setbacks, Captain Baker still took pride as the man who tried to capture Hitler. No one could take that away from him. The pride faded a week later, when a story appeared in Stars and Stripes, the military newspaper, about vandals destroying Hitler’s elaborate elevator.

The article was a crushing blow to Baker. Almost overnight he dropped from hero to criminal, and he thought he had better stay low. “You can never tell about the army,” he recalled. “They might have tried me for looting or wanted me to pay for the damages to the elevator. I figured I was lucky to get away with what I had and the last thing I wanted to do was embarrass some general who claimed to get to Berchtesgaden first.”

Baker packed his Hitler goods into his military trunk and shipped it home. The artifacts eventually ended up in his new welding shop in Dos Palos, California. Baker placed the glasses in the tin shop and often used them to share a drink of wine with farmers. Over the years, an occasional careless swipe of a hand or a hard slam of the shop door reduced the glasses, one after another, to glittering bits of trash. When they fell, Baker just shrugged his shoulders and continued to work.

Baker was a gregarious man and seldom without a smile, but it took some prodding to get him to speak about his exploits during World War II, and how the glasses with Adolf Hitler’s initials came to rest on his workshop shelf. Not one for sentiment, he eventually sold everything to collectors. He was not a man who lived in the past.

Many people have claimed to be the first ones into Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest. General Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote that the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division was the first to arrive: Herman Louis Finnell of that division said that he and Pfc. Fungerburg, his ammo carrier, were the first to enter. Newsreel footage showing 3rd Division soldiers drinking on the patio only proved they were there, but not necessarily first. Easy Company, 2nd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, the famed Band of Brothers, also claimed the honor, as have members of the French 9th Armored Division. French General Georges Buis claims that he and Paul Reption-Preneuf arrived first but left after a short visit.

Baker always laughed at such claims and said they really made no difference. The French refused to admit any Americans were there; the Americans, wanting all the glory, refused to recognize the French. “They can say what they like,” Baker commented. “I’m the one with the elevator panel.”

Author Richard Baker served in Vietnam with the 4th Infantry Division. His historical novel, First a Torch, about the siege of Dien Bien Phu, is used at French Foreign Legion headquarters in Aubagne, France, as part of French Foreign Legion history in Vietnam. He resides in Tacoma, Washington.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments