By Michael D. Hull

Itching for sea duty but forced to cool his heels with shore assignments, 40-year-old U.S. Navy Captain Daniel V. Gallery was a frustrated man when America went to war in December 1941.

A 1920 Annapolis graduate, Olympic wrestler, and battleship and destroyer officer before becoming a naval aviator and instructor, he commanded a scout-plane squadron, headed the aviation section in the Bureau of Ordnance, and then checked in as the naval air attaché at the U.S. Embassy in London in January 1941. When the Pearl Harbor attack thrust his country into World War II, Gallery was placed in charge of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet air base at Reykjavik, Iceland.

A lean, restless Irish-American who looked like a cross between singer Bing Crosby and actor Humphrey Bogart, the Chicago-born Captain Gallery applied his innate energy to the mission: leading a 12-plane squadron of Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats that provided cover to convoys up to a range of 500 miles, while cooperating closely with Royal Air Force Coastal Command.

In order to raise the shaky morale of his men in the cold and fog of bleak Iceland, Gallery enlisted the aid of a Navy Seabee battalion to construct a comfortable base for them. Making use of abandoned British Nissen huts, the Seabees built a “town” featuring streets, mock red fire hydrants, a gymnasium, bowling alley, and “palm trees” fashioned from metal pipes and burlap. He named the community “Kwitchyerbelliakin.”

Gallery endured his assignment for more than two years. Though a sensitive man with a ready sense of humor and considerable stamina, he grew increasingly fretful. After 20 years’ service in the Navy, during which he briefly commanded the USS Langley, America’s first aircraft carrier, he wanted to be at sea. Tuning in to BBC radio reports of the great battles at Coral Sea and Midway only made him chafe more. “I didn’t want to sit out the greatest war in history on the beach,” he said later. “I wanted a ship.”

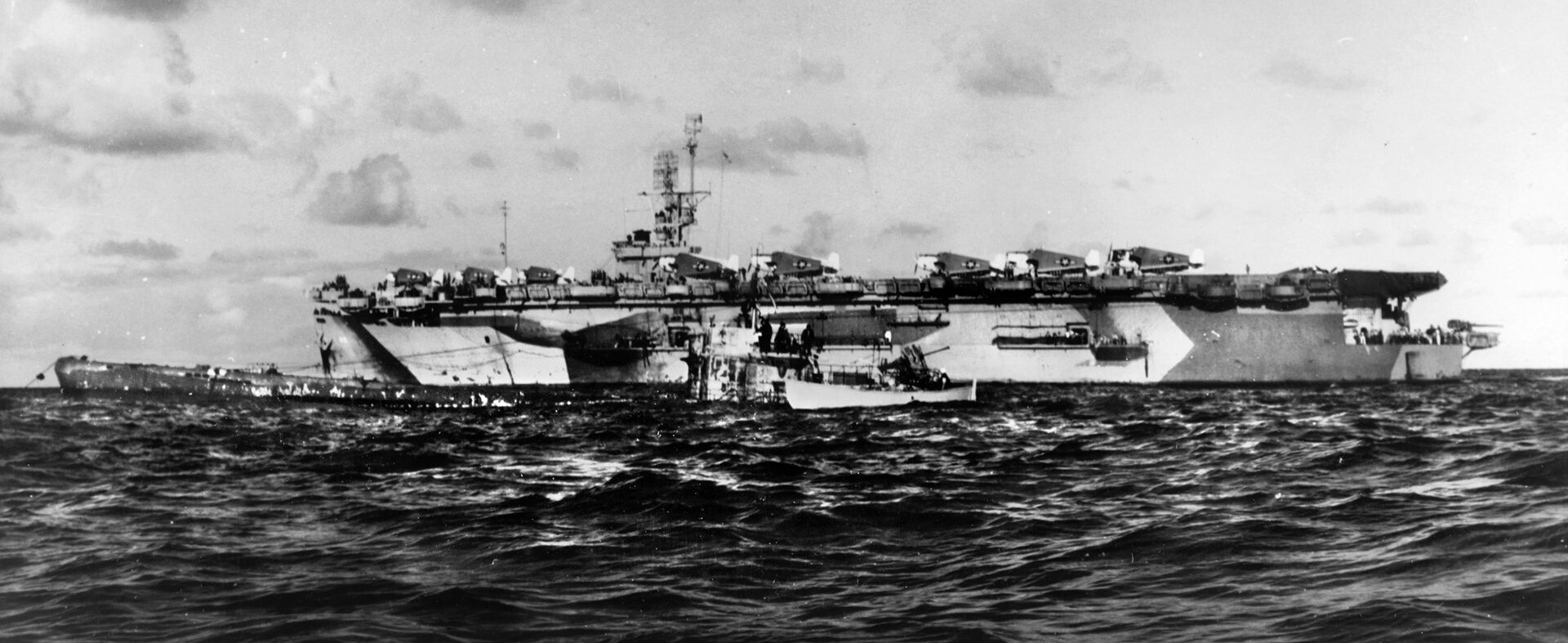

Finally, in May 1943, he got his wish and was ordered to report Stateside and take command of a brand-new escort carrier. The first few of an eventual 99 assembly-line “jeep carriers” were being hastily built by industrial czar Henry J. Kaiser in his sprawling shipyard at Vancouver on the Columbia River in Washington state. Soon after the sixth of the flattops, the Casablanca-class USS Guadalcanal (CVE-60), was launched on June 5, Gallery eagerly made his way there and took a hand in her fitting out.

When the 11,000-ton, 19-knot carrier was commissioned at Astoria, Oregon, on September 25, 1943, her 1,200-man complement lined up on the flight deck in dress blues while Gallery read the orders, the commission pennant was hoisted, and the ship’s chaplain offered a prayer. Swift to instill his fighting spirit in the mostly raw crew, the skipper said that if the ship did not have the Presidential Unit Citation flying from her foretruck within a year, “…we will be unworthy custodians of the great name being entrusted to our care.” He issued each man with a printed statement of his philosophy: “The motto of the Guadalcanal will be ‘Can Do,’ meaning that we will take any tough job that is handed to us and run away with it. The tougher the job, the better we’ll like it.”

The flattop weighed anchor on November 15, eased through the Panama Canal, and tied up in Norfolk, Virginia, on December 3. A month later, on January 3, 1944, the Guadalcanal took on board 12 Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo-bombers and eight Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters. Two days later, she put to sea for the Battle of the Atlantic as the flagship of Task Group 22.3, which also comprised the new 25-knot destroyer escorts Chatelain, Pillsbury, Flaherty, Pope, and Jenks. Gallery’s flattop was the first of Kaiser’s jeep carriers to wet her stem in the Atlantic; most of the others were destined for the Pacific theater. Besides Gallery’s ship, another seven American escort carriers were assigned to anti-submarine operations in the Atlantic. They were the Block Island, Bogue, Card, Core, Croatan, Santee, and Mission Bay.

On the bridge in his first carrier command, Gallery was ready for action as he led his task group eastward. His directive from Admiral Royal E. Ingersoll, commander of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, was simple: “Operate against enemy submarines.” The roving commission suited Gallery’s independent temperament. He knew that the U-boat pickings would probably be slim because the grim days of the big wolf packs were over. The British, Canadian, and U.S. Navies had turned the tide against the Germans in the Atlantic by mid-1943. But Gallery had a special objective in mind — one that no American skipper had yet pulled off.

Heading for Bermuda, the task group ran into heavy weather, during which two Wildcat fighters were badly damaged and had to be put ashore. The Guadalcanal group then steered northeastward. According to British Admiralty decrypts of German Enigma codes, U-boats were being refueled by “milch cow” tenders about 500 miles west of the Portuguese Azores. “The admiral simply told us to operate in the vicinity of the Azores,” said Gallery. “Those were the orders, and they gave you plenty of elbow room to write your own ticket.”

The task group headed for the U-boats’ “nesting area,” and Gallery launched planes on January 16. Just before sunset that day, two of the Avengers were flying about 300 miles northwest of the island of Flores when they sighted U-544, a milch cow, refueling a U-boat while another stood by awaiting its turn. One of the TBFs dived and made a run, firing rockets and dropping depth charges between the two boats. The U-boat was struck, and about 40 men began to abandon the milch cow.

A second Avenger loosed rockets and depth charges, and six more planes joined the attack, blasting the German boats. U-544 was destroyed, but the badly damaged U-boat was able to limp back to Brest harbor in northwestern France. The “Can Do” carrier had scored on her first time out. The crew cheered, but Gallery’s elation was short-lived. The planes had to be retrieved, and none of the pilots had landed on small carriers at night.

The first three planes landed safely on the flight deck, but the fourth veered off the side and nosed down in the gallery walkway. Efforts to push it over the side failed. “We were lit up like a barroom on a Saturday night because we had to,” said Captain Gallery. “They (the incoming pilots) were jittery, and they made some of the wildest passes I have ever seen.” In desperation, a fifth Avenger was waved in, but it bounced on the deck, somersaulted, and dived into the sea. The three crewmen were picked by a nearby destroyer escort.

But Gallery had had enough and ordered the other three planes to put down in the water. The destroyer escort switched on its searchlights and rescued the crews. The innovative skipper “decided we were going to learn to fly at night.” He inaugurated a night-flying training program and also ordered his crew to spend two weeks practicing how to dump a crippled plane off the carrier. His diligence paid big dividends.

When the task group returned to Norfolk on February 16, 1944, the Guadalcanal sailed proudly through Hampton Roads with a swastika painted on her bridge. But it had been a costly maiden voyage, with 15 of her 21 planes lost or unserviceable and five crewmen missing off the Azores. Hard lessons had been learned, however, and Gallery vowed that the next time his pilots took off to hunt U-boats it would be as qualified night fliers.

With a new squadron aboard, the “Can Do” carrier next put out from Norfolk on March 7, bound for Casablanca. The central Atlantic was quiet, and the pilots got in plenty of night-flying practice during the uneventful voyage. The Guadalcanal group left Casablanca on March 30 in support of a westbound Allied convoy.

Gallery broke away on April 8 when a “huff-duff” direction-finding report came in of a U-boat 60 miles distant, northwest of Madeira and bound for West Africa. She was U-515, commanded by 35-year-old Lt. Cmdr. Werner Henke, a ruthless, highly decorated ace who had sunk 25 Allied ships totaling 142,636 tons. When he torpedoed the 18,700-ton British troopship Ceramic 400 miles west of the Azores on the night of Dec. 7-8, 1942, Henke had surfaced, picked up one survivor, a British soldier, for information, and left 655 dead, including women and children.

Honing in on U-515’s probable location at sunset on April 8, 1944, Gallery launched Avengers and sent the destroyer escorts Pope and Chatelain to chase down a radar contact. The ships dropped depth charges, and the Pope reported an oil slick rising to the surface. Pillsbury and Flaherty raced to the scene, and two Avengers positively sighted U-515 and dropped depth charges. The U-boat dived and escaped, but she was being cornered.

On April 9, Easter Sunday, Captain Gallery started a dogged hunt for his quarry. When the U-boat warily surfaced to charge batteries, an Avenger dived and dropped depth charges. “We hounded him all night,” the carrier skipper reported. “Every time he’d pop up, we’d nail him again and chase him down again. Making a depth charge attack on a sub at night, or even in the daylight, is not a 100-percent thing. You don’t get the kill every time, and especially at night you don’t.”

Henke submerged to 787 feet while the Flaherty, Pillsbury, Pope, and more Avengers and Wildcats closed in for an attack that lasted six hours. Close explosions caused flooding in the U-boat. Desperate countermeasures by Henke failed to control U-515, and she shot to the surface stern-first amidst the American ships.

Chatelain and Flaherty raked the U-boat with deck guns, depth charges, and torpedoes, and Wildcats and Avengers loosed machine-gun fire and rockets. Finally, at mid-afternoon, Henke ordered abandon ship, and his crippled U-515 sank stern-first 175 miles northwest of Funchal, Madeira. Sixteen Germans had been killed. Henke and 43 of his men were rescued by the destroyer escorts and put aboard the Guadalcanal. Admiral Ingersoll signaled Gallery, “Well done!”

The carrier skipper was elated but less than satisfied. After the sinking, he concluded that he might well have realized his long-held goal. If he had been able to call on a trained boarding party in his group, he could have captured U-515 intact. So, he immediately ordered each destroyer escort to form a boarding party.

A few hours after the sinking of U-515, Gallery launched another search when sonar contact was made with a second U-boat off Madeira. After searching all night, planes from the Guadalcanal caught U-68 — surfaced and unsuspecting — at sunrise on April 10. Blasted with gunfire, rockets, depth charges, and a homing torpedo, the submarine broke in two and sank. Only one wounded crewman survived and was picked up. Another signal from Ingersoll exclaimed, “Exceptionally well done!”

“We got two kills the first two nights we flew,” Gallery proudly reported. “We had gone three weeks before, flying in the daytime, with no kills at all. The subs simply did not come up in the daytime…. If you wanted to do business out there, you had to fly at night. When we came back from the cruise and reported this, all the other CVEs started night flying.”

Meanwhile, the U-515 skipper and his men were interned when the Guadalcanal group returned to Norfolk on April 26. Though sullen and uncommunicative, Henke was glad to be in American rather than British captivity. He would have been tried for the Ceramic “atrocity.” Henke was shot during an exercise period on June 15 while trying to escape from the top-secret Fort Hunt interrogation center near Washington, D.C.

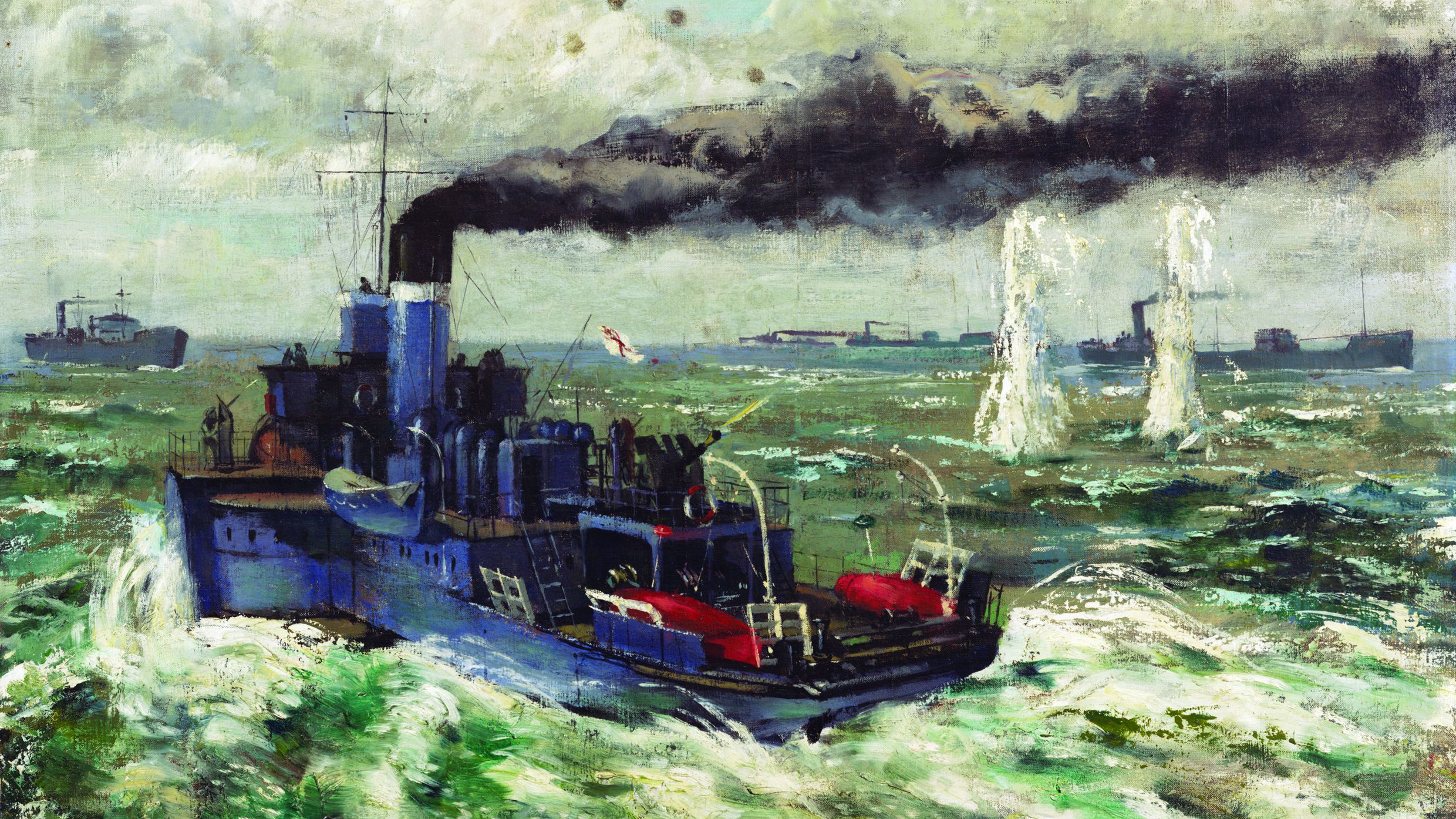

British, American, and Canadian naval units had gained the upper hand in the Battle of the Atlantic in the late spring and early summer of 1943 with the advent of longer-range patrol bombers, escort carriers, improved radar, better depth charges, and homing torpedoes. Shipping losses fell dramatically, but Admiral Karl Doenitz’s U-boats remained a deadly threat. In the spring of 1944, the Allies stepped up their offensive, focusing on the areas where replenishing milch cows kept the enemy submarines operating far from their bases.

Royal Navy ships discovered and sank two milch cows off Mauritius in February-March, and Admiral Ingersoll dispatched a task group led by the escort-carrier USS Block Island to take care of another U-boat “filling station” near the Cape Verde Islands, off the west coast of Africa. After two of the destroyer escorts, Bronstein and Thomas, sank three U-boats, two planes from the Block Island destroyed U-1059, an 1,100-ton milch cow, on March 19. But the Germans took revenge two months later. On the night of May 29, about 320 miles west of Madeira, U-549 slipped through the escort screen and sank the Block Island with three torpedoes. She went down quickly, but 951 crewmen were rescued. She was the only U.S. escort carrier sunk in the Atlantic during the war. In turn, the U-boat was sunk by two destroyer escorts.

When a report of the jeep carrier’s loss crackled into the Guadalcanal radio room, Captain Gallery cleared the lower deck and passed on the sad news. Then his Task Group 22.3 left the search area off Portuguese Guinea and steered northeast for a refueling stop at Casablanca. Along the way, a report from Allied codebreakers came in of a U-boat heading in the same direction, bound for its base in the Bay of Biscay.

U-505, a big Type IXC submarine commanded by 40-year-old Lieutenant Harald Lange, was low on fuel and forced to surface regularly to recharge her sapped batteries. The inexperienced commander Lange was taking a shortcut by hugging the Cape Verde Islands. U-505 was a hard-luck boat. She had been intercepted several times in the Bay of Biscay and had to return to port for repairs, and her second skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Peter Zschech, had committed suicide when he became despondent while out on patrol.

On the night of June 2-3, the Guadalcanal ran over the U-505’s reported position, and Lieutenant Lange heard Avengers dropping depth charges 60 miles away. Both vessels were heading northward on converging courses. The U-boat surfaced in the dark to recharge batteries. An Avenger flew within six miles of the enemy boat, and when she submerged, another flew right over her.

The American task group seemed to be getting closer to the quarry, but Gallery found himself in a quandary when his veteran chief engineer, Commander Earl Trosino, reported, “Captain, we’ve got to quit fooling around here and get into Casablanca. I’m getting down near the safety limit of my fuel.” When the sun rose on June 4, the skipper was frustrated. He thought his only potential target on this cruise was now out of range astern, but he could not pursue it because of his fuel state.

Suddenly, at 11:10 — on that clear, bright Sunday morning — the USS Chatelain blared a report of a possible sonar contact to Gallery’s carrier. The destroyer escort’s skipper, Captain Dudley S. Knox, radioed, “Contact evaluated as sub. Am starting attack!” The Chatelain wheeled and fired a salvo of 20 “hedgehog” shells into the air ahead. Two Wildcats from the Guadalcanal circled overhead and then dived with machine guns firing. One of the pilots, Ensign Jack Cadle, shouted on his radio, “Sighted sub! Destroyers head for spot where we’re shooting!”

As more Wildcats circled overhead like hawks and two other destroyer escorts boring in to assist, the Guadalcanal swung clear at top speed. “A carrier right smack at the scene of a sound contact is like an old lady in a barroom brawl,” explained Gallery. “She has no business there, and can do nothing but get out of the way.”

The Chatelain headed for the Wildcat’s bullet splashes and fired a spread of 12 depth charges. Seconds later, the sea heaved violently as one of the depth-charge patterns exploded close to the submerged U-505, rolling her over and blowing a hole in the outer hull. Her crewmen had been sitting down for lunch. The lights went out, and sailors, mess tables, crockery, and food were dumped into the bilges. “Water is coming in!” shouted one man, and an engineer reported that the German boat’s rudder was jammed.

Some panicky sailors rushed to the conning tower, shouting that the boat was sinking. Taking their word for it, Lieutenant Lange yelled, “Blow all tanks. Abandon and scuttle!” Above, the American ships’ bullhorns relayed Ensign Cadle’s words, “Sub is surfacing!”

At 11:21 am, 150 miles west of Cape Blanco on the coast of French West Africa, U-505 broke surface with white water streaming from her rusty-gray conning tower. Watching from the bridge of the USS Guadalcanal, Captain Gallery could not be sure if the U-boat had come up to abandon ship or to make a final, desperate attack on her hunters.

U-boat crewmen leaped from open hatches and met intense fire from the circling American ships. Lange was the first out and was hit in the leg by a .50-caliber round. Two men picked him up and dragged him overboard. The rest streamed topside, raised their hands in surrender, and jumped into the sea. Out of control, U-505 swung to starboard and settled by the stern. The crew had opened her sea cocks. Gallery broadcast to his ships, “I want to capture that bastard if possible!” At 11:27 am, he ordered his ships and planes to cease fire.

The destroyer escorts responded swiftly to Captain Gallery’s call. While the Flaherty stayed with the carrier and the Pope circled two miles away to watch for other U-boats, the Chatelain, Pillsbury, and Jenks got their motor whaleboats and boarding parties ready. Gallery shouted the order he had been planning for some time: “Away, boarders!” Carrying a nine-man boarding party led by Lt. (j.g.) Albert L. David, the boat from Captain George Casselman’s USS Pillsbury, was the first to approach the circling U-505. After the boat had chased the submarine around and finally caught up with her, a young sailor with a coil of rope jumped aboard and tied the whaleboat to the slippery stern of the U-boat. Watching through binoculars from half a mile away, Gallery shouted over his loudspeaker, “Hi-ho, Silver! Ride ‘em, cowboy!”

Lieutenant David and two other men then jumped onto the submarine. Fearlessly disregarding possible booby traps, demolition charges, or remaining Germans, they scrambled down the conning tower to the control room. It was deserted. The three boarders were unable to unjam U-505’s rudder or shut down the electric motors, but they closed sea cocks and disconnected demolition charges. In the radio room, they hastily gathered a priceless haul of Enigma keys, encoding machines, and signal books. For his valor and resourcefulness, David was later awarded the Medal of Honor.

The three destroyer escorts were busy picking up German survivors and trying to control the abandoned U-boat. The Pillsbury swung alongside in an attempt to take U-505 in tow. Casselman’s men got a towline to her, but the submarine’s big bow planes tore a long gash in the DE’s side and flooded her two main compartments. The Pillsbury had to back off, and Captain Gallery feared he was going to lose his prize.

Casselman radioed to Gallery that he did not think a destroyer could tow the big submarine, and engineer Trosino warned him that U-505 would sink unless she was towed. So, Gallery ordered, “All right, destroyers stand clear. I’ll take her in tow myself.” The Guadalcanal backed in with her stern close to the U-boat’s bow, and a towline was thrown over. By this time, a 20-man boarding party led by Trosino was aboard the submarine. With great difficulty, Trosino and his men put a steel cable through the U-boat’s bullnose and tied it off. An American flag was hoisted on U-505’s bridge.

“We finally got her in tow and started to haul her away,” Gallery reported. “It soon developed that she sheared way out to starboard until the towline was as taut as a bow string— but, anyway, we were able to drag her along because the rudder was jammed. We were able to tow her all that afternoon.” A total of 58 German survivors were taken aboard the Guadalcanal.

The flattop and three destroyer escorts set a northward course for Casablanca, leaving the Pope to shepherd the damaged Pillsbury until emergency repairs could be completed. Captain Gallery’s elation at fulfilling his dream and capturing a U-boat was tempered that evening when his engineers reminded him that he did not have enough fuel to reach Casablanca. “The threat of running out of fuel almost won a place in naval history comparable to the foolish virgins who ran out of oil,” he commented ruefully.

He sent an urgent message to Atlantic Fleet headquarters, reported that he had captured an enemy submarine and was low on fuel, and asked permission to put in to the nearest Allied port, Dakar on the French West Africa coast. The immediate response was: “Nothing doing on Dakar. Take her to Bermuda (2,500 miles away). We’ll have a tanker rendezvous with you with fuel.” Dakar was denied because it was infested with German spies. If Berlin learned of the capture of U-505, Washington reasoned, the Germans would undoubtedly make “major changes” in U-boat Enigma security and perhaps neutralize Allied codebreakers on the eve of the postponed Operation Overlord, the D-Day landings in Normandy.

On the day of the capture, June 4, Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, the British First Sea Lord, sent an urgent cable to his American counterpart, Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations. It read, “In view of the importance at this time for preventing the Germans suspecting a compromise of their ciphers, I am sure you will agree that all concerned should be ordered to maintain complete secrecy regarding the capture of U-505.” Captain Gallery had made U.S. naval history, but the acerbic Lord was so angry at him for possibly jeopardizing Allied mastery of the German Enigma system that he threatened to court-martial him. Cooler heads eventually prevailed.

By the evening of June 4, the Guadalcanal boarding party was back on the carrier. “We weren’t at all sure she’d (U-505) stay afloat, so I didn’t leave anybody aboard during the night,” said Gallery. The night of June 4-5 was tense as excited sonar and radar operators reported echoes and blips, and lookouts said they had sighted periscopes. “It sounded like we were completely surrounded by German U-boats, and they were closing in on us,” Gallery recalled later. So the carrier put on speed—and the towline broke. The American ships circled U-505 during a maximum U-boat watch that night, and the pause enabled the slow-moving Pope and patched-up Pillsbury to rejoin the group.

Early on the morning of June 5, a stronger wire cable was attached to U-505, but towing was still exceedingly difficult because of her jammed rudder. Accompanied this time by Captain Gallery, engineer Trosino and his team clambered back aboard the submarine. After making sure there were no remaining booby traps inside, they made their way through the stern torpedo room and righted the rudder. The task group resumed its slow northwestern voyage toward British Bermuda. Towing the U-boat, the Guadalcanal could not make more than eight knots. “That was as fast as I dared go,” said Gallery. He kept his planes in the air because “we were right in the middle of a submarine operating area at the time, so I figured we had to protect ourselves.”

Several vessels had been sent from Casablanca to succor Gallery’s ships. They were the 8,560-ton seaplane tender Humboldt, the 20,960-ton fleet oiler Kennebec, and the fleet tug Abnaki. The ships rendezvoused with the “Can Do” carrier on June 7, and she and her escorts were amply refueled for the voyage to Bermuda. The tug took the captured U-boat in tow in mid-ocean, and the task group proceeded. Realizing the need to keep the capture secret, Gallery ordered the U-505 coding machines, books, and ciphers to be placed in “mail sacks” aboard his fastest destroyer escort, the USS Jenks. She then sped ahead to Bermuda, and the captured material reached the Navy Department on June 12.

Finally, under tight security ordered by Washington and the British Admiralty, the Guadalcanal and her destroyer escorts steamed into harbor at Bermuda on June 19. Aware of Gallery’s weakness for publicity, Admiral King cautioned him to lie low and to seal the lips of the 3,000 sailors and airmen in his task group. A team of high-ranking Navy Department officers, meanwhile, flew in to inspect U-505 and interrogate the prisoners.

The arrival in Bermuda was the crowning moment in Captain Gallery’s career. His carrier, which had been in action for only five months, was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, and he had realized his goal of capturing a U-boat. The seizure of her Enigma equipment and logs, he said, was “one of the main reasons for our high rate of sinkings during the last year of the war.”

U-505 was not the first German submarine to surrender during World War II. U-110 was captured by the Royal Navy destroyer HMS Bulldog on May 9, 1941, and U-570 surrendered to a Lockheed Hudson patrol bomber of Royal Air Force Coastal Command on August 27, 1941. Gallery achieved a double distinction, however. U-505 was the only U-boat captured by the U.S. Navy during the war and the first foreign vessel seized by an American ship since the 14-gun British East India Company brigantine Nautilus surrendered to the 18-gun sloop Peacock in the Sunda Strait on June 30, 1815. This was the final naval action of the War of 1812.

The Allies made sure that Gallery’s historic coup remained a secret. The Germans, preoccupied with trying to repulse the great Normandy invasion on June 6, 1944, assumed that the U-boat had been sunk by Allied planes and made no major changes in their Enigma intelligence system. U-505 remained at anchor in Bermuda under strict security for the rest of the European war.

“The British had very tight control over everything going out by mail, telephone, radio, and press,” said Gallery. “And they were able to clamp an iron-clad lid on the thing so word wouldn’t get out. If we’d brought her into Norfolk or any other place in the United States, it would have been out in no time.” The U-boat’s surviving crewmen were interned, isolated from other enemy prisoners, and denied access even to the Red Cross. Their families knew nothing about them until they were repatriated in 1947.

After Germany surrendered on May 7, 1945, the Navy moved U-505 to the United States. After highlighting a war-bond-selling voyage along the Eastern Seaboard, she was tied up in the Portsmouth Navy Yard at Kittery, Maine.

Captain Gallery became assistant director of the plans division under the chief of naval air operations in September 1944, and was given command of the new 27,200-ton carrier USS Hancock in the Pacific theater the following year. The flagship of Vice Admiral John S. McCain, the Essex-class flattop took part in actions off the Philippines, Okinawa, and the Japanese home islands.

Gallery was promoted to rear admiral in December 1945, and his gallant Guadalcanal was decommissioned the following July. He went on to hold a number of key sea and shore commands through the 1950s, including the flagship USS Coral Sea and Carrier Division 6 in the Mediterranean; the Atlantic Fleet hunter-killer force; the Glenview (Illinois) Naval Air Station; the Ninth Naval District at Great Lakes, Illinois, and the 10th Naval District at San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Energetic and outspoken as ever during the Cold War, the “Can Do” skipper issued a controversial “memorandum” calling for the building of carriers with nuclear-strike capability, and loudly protested the conviction of Admiral Karl Doenitz, commander of the German U-boat fleet in World War II. “Nuremberg was a kangaroo court and a travesty on justice,” Gallery declared. “The trial of Doenitz was an outstanding example of barefaced hypocrisy. His conviction was an insult to our own submariners in the Pacific who waged unrestricted warfare the same as the Germans did in the Atlantic.” Gallery took time to visit Germany and look up his former enemy, Lieutenant Lange. The two men dined, visited a theater, and “got to be good friends” during a day in Hamburg.

Lange’s U-505, meanwhile, languished without maintenance for a decade in the Portsmouth Navy Yard, while plans were made several times to sink her in the Atlantic Ocean. Gallery protested vigorously each time and fought to have the U-boat moved to his Chicago hometown. With the aid of a mayoral committee, the city’s Navy League chapter, the Chicago Tribune, and an act of Congress, U-505 was eventually transported to Chicago and placed on permanent display at the Museum of Science and Industry.

Detached from the Navy in November 1960, the year that the Guadalcanal was scrapped, Admiral Gallery retired to Vienna, Virginia, wrote nine books, and was with his wife when she died at Bethesda (Maryland) Naval Hospital on January 16, 1977.

Author Michael D. Hull passed away some months ago. During his lifetime, he was a frequent contributor to WWII History, writing on a variety of subjects from his Enfield, Connecticut, home.