By Kevin Seabrooke

In the dead of winter at the base of a hill just 20 kilometers south of Seoul, Korea, Easy Company’s 1st platoon found themselves pinned down by a continuous stream of small arms, automatic, and antitank fire coming from above.

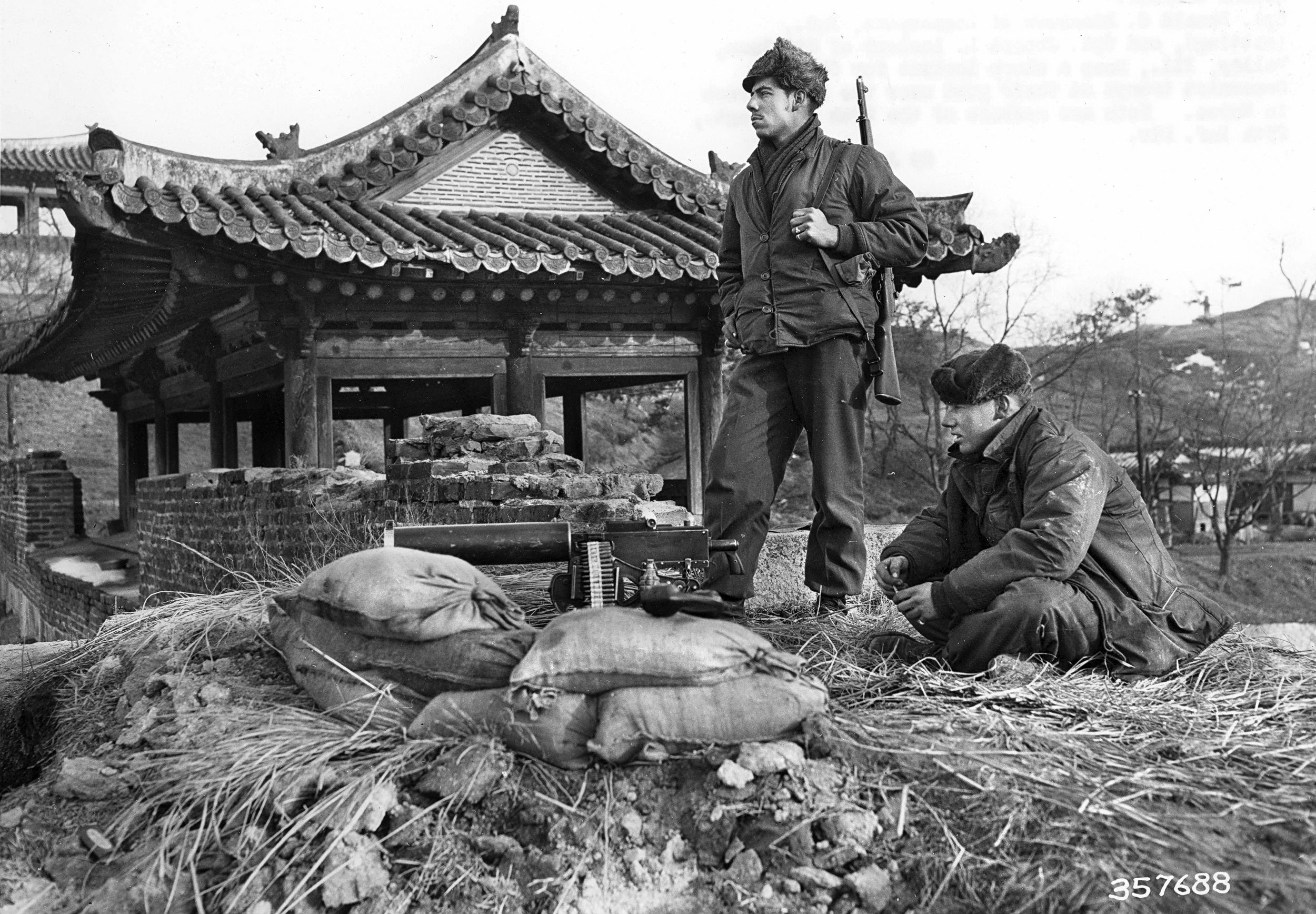

Two platoons under U.S. Army Captain Lewis L. Millett had been leading the way, riding north on tanks near Anyang when movement was spotted atop a nearby hill. Ordering the tanks off the road, Millett got his men deployed along the dike of a rice paddy.

As they prepared to move out, enfilading fire started up from a previously unknown Chinese position, raking through 1st platoon. The situation worsened a few minutes later when a .50-caliber machine gun jammed on one of the tanks that had been providing cover fire.

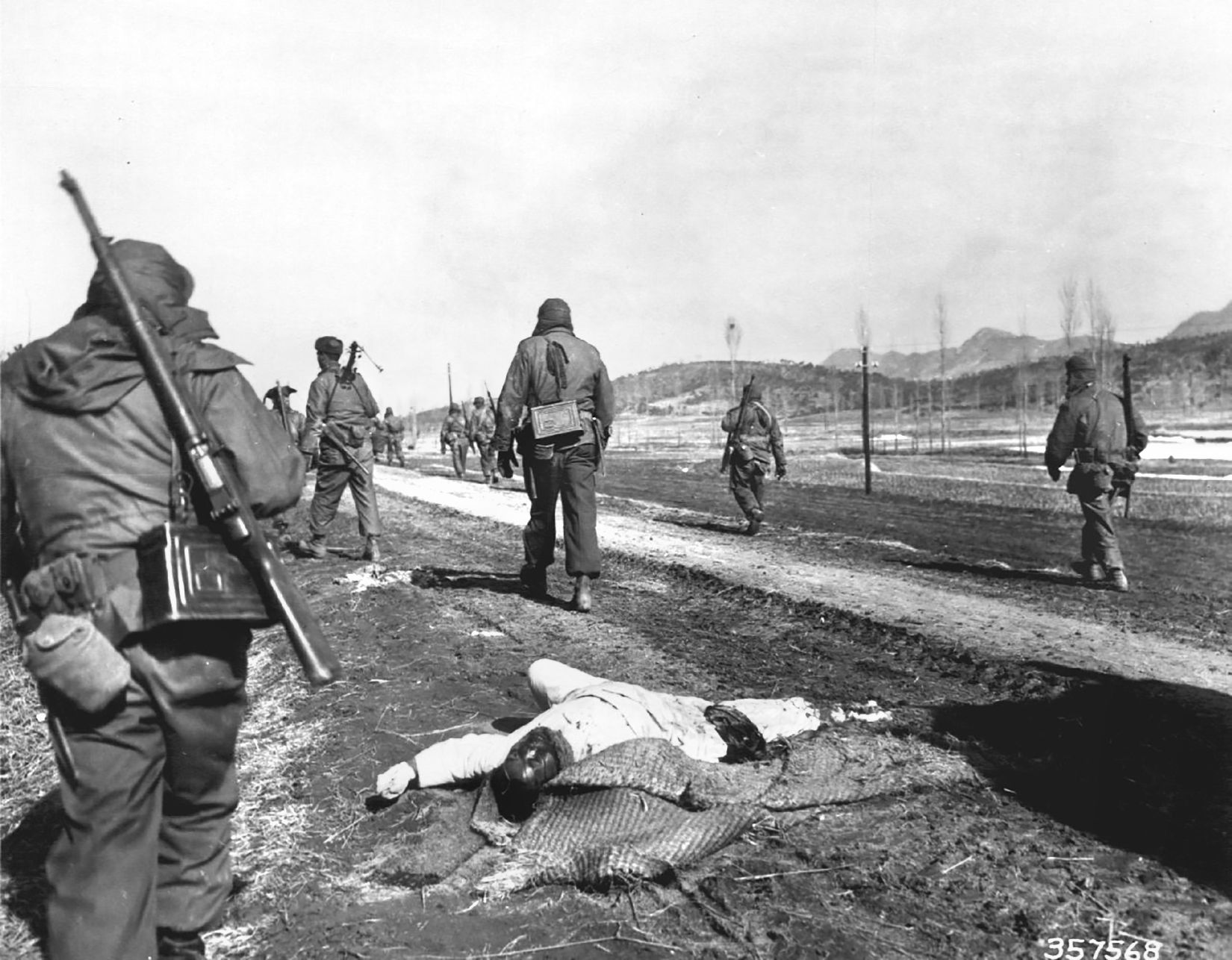

After weeks of tactical withdrawals south from the 38th parallel as Chinese communist troops poured in from North Korea—first to the South Korean capital of Seoul, then to a line below Osan and Wonju—the Eighth Army under new commander Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway went on the offensive on January 25, 1951, with Operation Thunderbolt. Anticipating that the Chinese and North Koreans were overextended on tenuous supply lines, Ridgway tasked the 27th Infantry Regiment, nicknamed the “Wolfhounds,” to be the vanguard of the all-out United Nations assault.

And in the battle-hardened World War II veteran Millett, Ridgway had the perfect leader on point.

It was now February 7 as Millett scrambled across the bullet-spattered ground, shouting to the 1st platoon sergeant to have the men fix bayonets and charge. Screaming over the sound of gunfire for them to follow him, he raised his own rifle and bounded over the frozen hillocks and ditches.

At the base of the hill, Millet hit the ground in front of an outcropping of rock and waited for the rest of the platoon to catch up with him. The sergeant and about a dozen men soon piled in around him. Many in the platoon that hadn’t reacted immediately had been cut down when the Chinese machine-gunners zeroed in on them.

The small group dodged Chinese bullets, moving from rock to rock until they reached the first of three small knobs, some 20 meters below the middle and far knobs. Spotting a machine gun position to the left, Millet ordered a Browning Automatic Rifle to fire at it just as another soldier noticed a foxhole with eight Chinese soldiers squatting in it just ten yards from him. Throwing grenades and firing his carbine as he charged the position, Millet killed them all.

Millet then radioed for 3rd platoon to come up the hill and once they were in position, shouted “Attack straight up the hill!”

With bayonets fixed and rifles at high port, the Wolfhounds charged up the hill screaming Chinese phrases as they ran. At the first line of foxholes, they plunged in with bayonets first and the cries of agony could reportedly be heard over the roar of battle. Millet got out so far in front of his men he had to dodge grenades from both sides as he charged an antitank gun firing at him point blank. He took it out with a few grenades of his own.

They had come far, but were not quite at the top when a cluster of eight grenades came down the hill. Millet dodged and scrambled as he ran, avoiding them until the ninth hit and sent shrapnel into his back and legs. Bleeding and in pain, Millet continued to run forward, reportedly urging his men to use grenades and their bayonets.

Finally at the top, Millet jumped into a v-shaped slit trench and impaled the first man he came to so deeply that he had to fire his rifle to pull it out of the body. He immediately stuck it through the throat of the next soldier. A third Chinese soldier took aim but had Millet’s blade through his chest before he could fire.

By this point, Millet’s men had caught up with him and the charge continued with bullets, grenades and bayonets until all the bunkers and foxholes on the hilltop were filled with dead and dying Communist soldiers. Millet held his bloody rifle over his head to signal those down on the road that the hill, soon to be forever known as “Bayonet Hill,” had been taken.

Nine of Millet’s men were killed in the attack. The official count of dead Communists on the hill was 47, with 30 of them killed by bayonet. Down the opposite slope were 50 more bodies killed by bayonet wounds or bullets. Witnesses reported at least 100 Chinese had escaped.

Five months later, on July 5, Millet received the Medal of Honor from President Harry S. Truman in a ceremony in the White House Rose Garden. Colonel Raymond Harvey, Master Sgt. Stanley Adams and Sgt. Einar Ingman also received the Medal of Honor that day for actions in Korea.

Millet’s Medal of Honor citation notes that “his dauntless leadership and personal courage so inspired his men that they stormed into the hostile position and used their bayonets with such lethal effect that the enemy fled in wild disorder.”

Millett’s name is forever linked to what the historian S.L.A. Marshall called in his book, Battle at Best, “the most complete bayonet charge by American troops” since the Civil War.

But for Millett, it wasn’t even the first time he’d led a bayonet charge that week. Only two days earlier, he’d done something similar. The idea had come to him after reading summaries of captured Chinese communications that claimed Americans were afraid of close combat, including bayonets. Millett was incensed, telling one interviewer that he said at the time “that’s a blankety-blank lie! Both my great-grandfathers that fought in the Civil War used bayonets all the time, and we’ll teach those son-of-a-bitches a lesson!”

Millett said he went out and got bayonets for the men in his unit and had them sharpened. After training his troops in its use, he declared that he intended to lead attacks with bayonet assaults. Though, Millet said, after three such sorties, he was ordered not to continue because “they were afraid I’d get killed—probably would have.”

In a later interview, Millett said that the Medal of Honor wasn’t just his, but also belonged to the 100 men of his unit that charged with him.

“You can go running up the hill all by your lonesome and get shot!” he said. “If they all hadn’t gone, I’d be dead—just as simple as that.”

Lewis Lee “Red” Millet was born in Mechanic Falls, Maine, on December 15, 1920. He was living with his mother in Massachusetts when, at 17, he joined the National Guard as part of the 101st Field Artillery Regiment. Millet enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1940. But he was eager to see action and, as America was still not in the war, he went north after a few months to join the Royal Canadian Artillery Regiment. By the time he was sent to Europe, the U.S. had entered the war after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Millet, who had been working as a radar operator in the Canadian army during the Blitz, turned himself in at the U.S. Embassy in London. He recalled later that the sergeant he spoke to told him he could just transfer to the U.S. Army and nothing would come of his desertion.

He was assigned to the U.S. 1st Armored Division, going to North Africa as an antitank gunner. In Tunisia, he earned a Silver Star for driving a burning halftrack full of ammunition away from camp and ditching it before it blew up. He was also credited with shooting down a German fighter with a vehicle-mounted machine gun.

Six months later, in Italy, Millett’s service records finally caught up with him—after he had earned Silver and Bronze stars. He was court-martialed and found guilty of desertion and fined $52.

“But at that time I had only been getting $10 a month because they had no records of me,” Millett told an interviewer later. “And so I had accumulated all this money—I got about $6,000 when they finally court-martialed me and they fined me $52 and made me a second lieutenant.”

After World War II, Millett served for four years in the 103rd Infantry of the Maine National Guard before being recalled to the Army, then assigned to the 27th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, and being deployed to Korea.

After Korea, Millett went to the Infantry Officers Advance Course and Ranger School as a major and was then assigned to the 101st Airborne Division as an intelligence officer.

During the Vietnam War, Millett helped establish the Vietnamese Ranger School and the Commando training program in Laos before moving to the Command and General Staff College. He was also a military advisor to the controversial Phung Huang (Phoenix Intelligence Program) which sought “to attack and destroy the political infrastructure of the Viet Cong.” He retired from the Army in 1973 as a Colonel.

In addition to the Medal of Honor, Millett also received the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star, two Legions of Merit, three Bronze Star Medals, four Purple Hearts, and three Air Medals.

Millett also received the Combat Infantryman Badge, Ranger Tab, Good Conduct Medal, American Defense Service Medal, American Campaign Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, World War II Victory Medal, Army of Occupation Medal, National Defense Service Medal, Korean Service Medal, Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal and the Vietnam Service Medal.

Internationally, he recieved the Vietnam Cross of Gallantry, the Croix de Guerre, the United Nations Korea Medal and the Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal.

At the National Infantry Museum at Fort Moore (formerly Benning) in Columbus, Georgia, “Millet’s Bayonet Attack” is part of an exhibit called “The Last 100 yards.” According to the museum, the U.S. Infantry has, since its formation in 1775, “owned the last 100 yards of the battlefield.” The exhibit features life-size dioramas of infantry battles through history, including Yorktown, Antietam, Soissons, Normandy, Corregidor, Soam-Ni (Millet’s bayonet charge in Korea), LZ X-Ray, and Iraq.

Millett’s Medal of Honor citation and tradition at Osan Air base in Korea hold that the hill he and his men charged up was 180. Subsequent research indicates that it was more likely Hill 80, some 12 miles further north near the town of Anyang. Annual services hosted by U.S. Army 35th Air Defense Artillery Brigade and the Colonel Lewis L. Millett Hill 180 Memorial VFW Post 8180 are still held at the air base at the Battle of Bayonet Hill/Hill 180 Memorial on “Millet Road” on Hill 180. Bayonet Hill is still used as an educational tool for leadership and building esprit de corps.

Millett, who retired as a colonel, died at the age of 88 on November 14, 2009, from congestive heart failure in Loma Linda, California.

Decades ago worked in a bunker dug into Hill 180 at Osan. Also worked in facilities at the top of the nearby Hill 170.

Its a shame that the Army and National Guard has given up on the bayonet, a real loss for riot control and crowd management in crisis situations.