By Michael E. Haskew

By the end of March 1945, the Western Allied armies were across the Rhine, the last major geographical barrier to an all-out final assault against the Third Reich.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme commander of Allied forces in the West, had looked forward to the opportunity to destroy Nazi resistance, march triumphantly on Hitler’s capital—Berlin—the black heart of the enemy, and end World War II in Europe for good. However, he had recently received word that the Soviet Red Army had crossed the Oder River and was, in some places, less than 30 miles from Berlin.

On March 19, Eisenhower had invited his friend and XII Army Group commander General Omar Bradley to accompany him to Cannes, on the French Riviera, for a few days of rest and relaxation. While there, Eisenhower sought the perspective of his old comrade and fellow member of the U.S. Military Academy graduating class of 1915.

Eisenhower asked Bradley what he thought about a final, all-out push for Berlin. Bradley thought the effort would cost 100,000 casualties and added wryly that it was “a pretty stiff price to pay for a prestige objective, especially when we’ve got to fall back and let the other fellow take over.”

Bradley’s observation resonated with Eisenhower, and he was correct in that the military conquest of Berlin, either by forces from the East or West, would be followed by the implementation of shared occupation of the capital city, which was 100 miles deep inside the proposed post-war Soviet zone of occupation. Eisenhower thought for a while and then broke protocol, directly contacting Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin to inform him that the Western Allied armies intended to occupy the Ruhr, the industrial heart of Germany, rather than assaulting Berlin directly. If their efforts could be coordinated, Eisenhower would leave to the Red Army the nasty business of fighting it out with diehard Nazis in the streets of Berlin.

And so it was. On April 1, 1945, Stalin called two of his most prominent and successful commanders to the Kremlin in Moscow. He asked the rivals, Marshal Georgi Zhukov of the 1st Belorussian Front and Marshal Ivan Konev of the 1st Ukrainian Front, point-blank, “Who will take Berlin?”

Konev quickly retorted, “We will!” Both commanders had played key roles in the smashing Red Army operations leading up to this watershed moment. The Soviets had booted the Nazi Wehrmacht out of Russia after a bloody months-long war of attrition, and Soviet offensive operations in 1944 from Odessa in the south to Leningrad in the north had become known as “Stalin’s Ten Blows.” In the spring of 1945, East Prussia, the Baltic States, and Pomerania were already occupied by the Soviets, and the time had come for supreme retribution, the utter destruction of the enemy and the capture of Berlin, the lair of the “Fascist beast.”

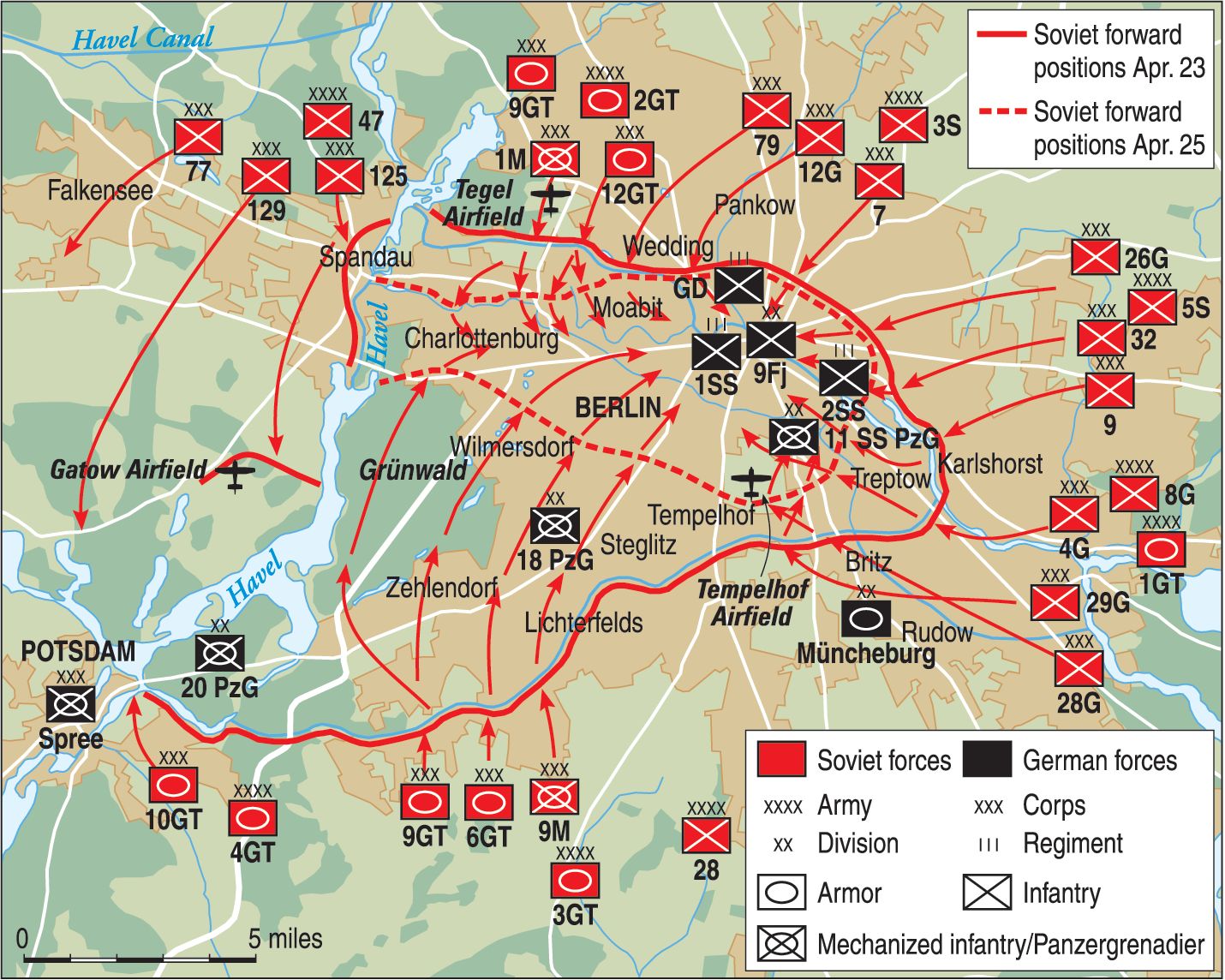

Stalin gave Zhukov and Konev succinct orders for the coming Battle of Berlin. Konev was to approach the city from the south, while Zhukov came up from the north and east. The two massive Fronts (roughly equivalent to Western army groups) would strangle and then trample the Berlin defenders in a massive pincer, squeezing the Germans in an ever-shrinking defensive perimeter until they were annihilated.

Two weeks later, the end game began as the Red Army, poised along the banks of the Oder and Neisse rivers, unleashed a furious artillery bombardment. Well over a million troops were committed, and Konev advanced 13 kilometers the first day while Zhukov pushed toward the Seelöw Heights, a promontory just east of Berlin.

Zhukov had underestimated the resolve of the Seelöw Heights defenders, remnants of German Army Group Vistula under the capable command of Colonel General Gotthard Heinrici. Although substantially outnumbered and outgunned, these Germans were inculcated with Nazi fervor and willing to die in order to hold the ridge. Just before the Soviets unleashed their terrible initial bombardment of the Seelöw Heights, the Germans had pulled back from their frontline bunkers and machine-gun nests. Therefore, much of the Soviet artillery fire failed to inflict serious damage.

As Zhukov’s troops and tanks moved forward, they were met with galling fire while German tanks and tank-killing infantry squads stalked them. The Germans inflicted heavy damage on the Soviet armored vehicles—made easy targets as they were silhouetted by their own searchlights. Zhukov’s advance stalled. Four days of horrific fighting were required for the 1st Belorussian Front to break through at Seelöw Heights, and in the wake of the Red Army advance 30,000 Soviet soldiers were dead while 12,000 Germans had been killed in action.

When reports of Zhukov’s delay reached Stalin in Moscow, he flew into a rage and ordered Konev to redirect the wide sweep he had planned with the Ukrainian Front spearheads and send his tanks directly toward Berlin. Stalin’s order intentionally fanned the flame of the rivalry between Zhukov and Konev, both commanders vying for the prestigious honor of capturing the Nazi capital city. Casualties were a secondary concern in the race to take Berlin.

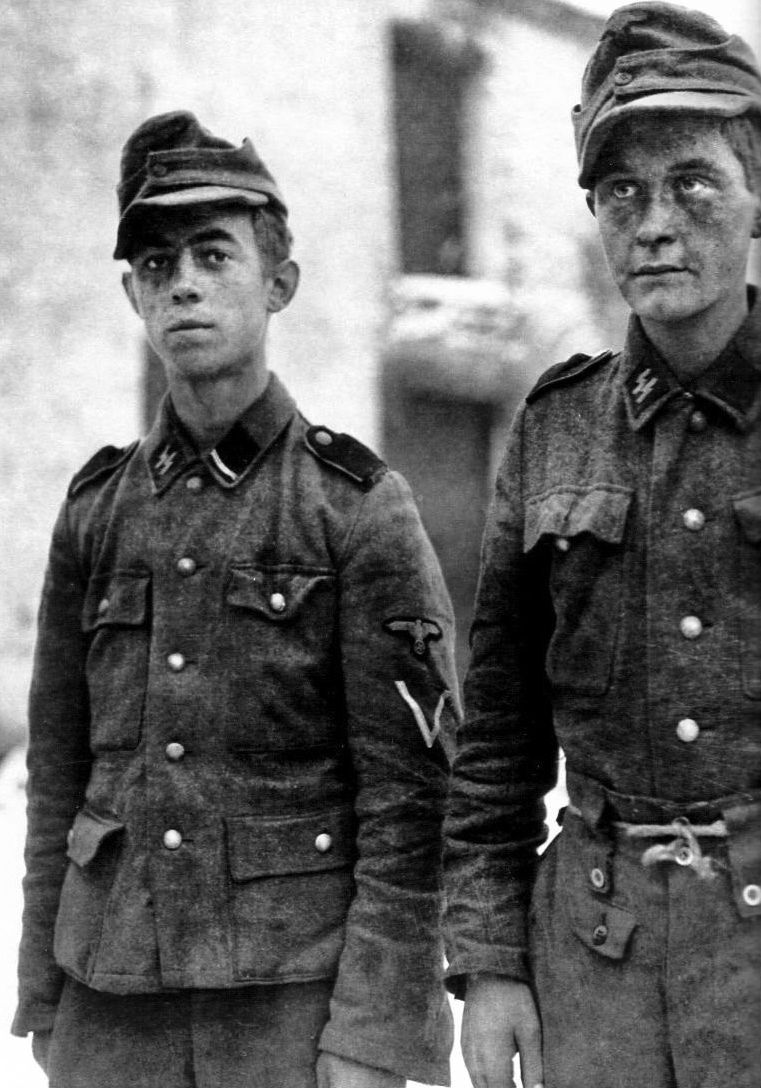

Four days after the Red Army offensive was launched, Adolf Hitler observed his 56th birthday. April 20, 1945, was a somber occasion as the Nazi leader emerged from the underground Führerbunker, a subterranean labyrinth of two levels 50 feet below the garden of the Reich Chancellery amid a cluster of administrative buildings known as the Citadel near Berlin’s Königsplatz. The Führer was above ground just long enough to pat the cheeks of several boys who had displayed conspicuous bravery fighting the marauding Soviets. He congratulated them for their courage and awarded them the Iron Cross.

Even as he smiled faintly, Hitler was a physical shambles, a shadow of his former self. His hands shook noticeably, most likely due to progressive Parkinson’s Disease. A chemical cocktail of Benzedrine eye drops laced with cocaine kept him somewhat alert, but he shuffled as he walked, hunched in an ill-fitting overcoat. He suffered from severe stomach pain and consumed barbiturates to induce fitful sleep. He was prone to moments of dejection followed by outbursts of uncontrollable rage. The walls were closing in.

Soviet long-range artillery marked the Führer’s birthday by opening fire on the center of Berlin, and Hitler received word that Zhukov had broken through at Seelöw Heights. Just as the Soviet guns were preparing to open fire, a Red Army news correspondent happened upon several artillery pieces at the ready. He wrote later, “‘What are the targets?’ I asked the battery commander. ‘Center of Berlin, Spree bridges, and the northern Stettin railway stations,’ he answered. Then came the tremendous words of command: ‘Open fire on the capital of Fascist Germany.’ I noted the time. It was exactly 8:30 a.m. on 22 April. Ninety-six shells fell on the center of Berlin in the course of a few minutes.”

Konev was charging across open country, legions of the superb T-34 medium tanks supporting the infantry with the 3rd Guards Army and the 4th Guards Tank Army in the van. There was more disturbing news. A third Soviet Front, the 2nd Belorussian under Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky, had breached the lines of the 3rd Panzer Army and begun a thrust toward Berlin as well. The old men and boys of the Volksstürm and the Hitler Youth were already in the lines to bolster the hodgepodge of German Army and Waffen SS units poised for the death struggle in Berlin.

By April 25, a Guards rifle regiment of the 1st Ukrainian Front made contact with troops of the U.S. 69th Infantry Division at Torgau on the Elbe River, splitting the Third Reich in two. On the same day, Soviet forces completed the encirclement of Berlin. The western advance of the 1st Ukrainian Front prevented the German 12th Army, under the command of General Walther Wenck, from coming to the aid of the Berlin defenders, and the 4th and 9th Panzer Armies were surrounded as well.

Immediately, Soviet probing attacks tested the defenses of Berlin proper, which the Germans had arranged in three concentric rings, further identified in nine sectors. The outermost ring stretched roughly 60 miles, its circumference including the outskirts of the capital city. It was a mere shell of a defense, consisting primarily of roadblocks, shallow trenches, mounds of rubble blocking roadways, and barricades of felled trees and otherwise useless vehicles. The advancing Red Army units breached this thin line swiftly and in several locations prior to their main assault.

The second defensive ring ranged about 25 miles and incorporated shell-scarred buildings and other obstacles in its composition. Favorable terrain and stations along the route of the S-Bahn, Berlin’s public transportation system, were included. The inner ring took advantage of the huge, stoutly constructed buildings that had once housed the departments and ministries of the Nazi government. German soldiers turned these buildings into defensive strongpoints bristling with machine-gun emplacements and anti-tank positions on each floor. Six gigantic concrete-reinforced flak towers, each of them studded with heavy antiaircraft guns, were part of the inner circle. These massive structures were virtually impregnable to artillery fire or aerial bombardment unless they received a direct hit.

Eight of the nine defensive sectors were labeled A through H and radiated from the center of Berlin through the defensive rings and outward to the perimeter. The ninth, designated Z, was heavily defended, primarily by a fiercely loyal contingent of Hitler’s personal SS bodyguard. Berlin was a sprawling city, encompassing 340 square miles, and the defenders also made the most of the natural barriers that were available. The course of the Spree River was heavily fortified, as were the Teltow and Landwehr Canals.

To a man, the Red Army soldiers knew that their primary objective was the Citadel, where the nexus of Nazi government had presided in its collection of imposing buildings north and east of the Tiergarten, a large residential district and park that included the formerly world famous Berlin Zoo.

While estimates of the strength of the German defenders in Berlin vary widely, it is believed that from 100,000 to 180,000 soldiers of the SS, Hitler Youth, and Volkstürm had been scraped together under the command of General Helmuth Weidling, who was personally appointed by Hitler on April 23 to lead the defenders during the death throes of the Reich.

The Red Army advanced toward the center of the Nazi capital on four primary axes, moving along the Frankfurter Allee from the southeast, Sonnenallee toward the Belle-Alliance-Platz from the south, further from the south toward the Potsdamer Platz, and straight toward the Reichstag from the north. Although a symbol of the German state, the Reichstag building had not been in use since 1933, when it was gutted by a devastating fire probably set by the Nazis and then blamed on Communists. Still, the structure was a powerful symbol of the German nation, and its capture would be symbolic of the Soviet victory.

The Soviets quickly penetrated the outer defenses of Berlin, and on April 26, the 8th Guards and 1st Guards Tank Armies battled through the second defensive ring. They soon crossed the line of the S-Bahn and assaulted Tempelhof Airport. West of this action, the 1st Belorussian Front fought for two days to reach the banks of the Spree and entered the suburb of Charlottenburg.

Fighting reached the Tiergarten on April 28, and that same day the Potsdamer Strasse Bridge across the Landwehr Canal was taken intact. After dawn on the 29th, the 3rd Shock Army stormed across the Moltke Bridge over the Spree. To the left of these troops, the Reichstag building fronted the Königsplatz. The old structure, already scarred with the black stains of the great fire, was defended by roughly 6,000 German soldiers, while the approaches were heavily mined and machine-gun nests were scattered about. A few artillery pieces and a handful of available tanks had also been committed to the Reichstag defense.

As they moved against the Reichstag building, the Soviets also assaulted the Interior Ministry building. Progress was slow as the Germans contested every yard of territory and every floor of the structure. Early on the 30th, Red Army troops occupied Gestapo headquarters on Prinz Albrechtstrasse, but a furious German counterattack forced them out. Nevertheless, most of the diplomatic quarter was in Soviet control by the end of the day.

The fighting for the Reichstag raged, meanwhile, as the 79th Rifle Corps began its decisive attack on the structure. Brave soldiers of the 150th Rifle Division sprinted across the open ground of the Königsplatz in a frontal assault while German machine guns spewed bullets and sent many attackers spinning down in mid-stride. As other Soviet divisions joined the Reichstag assault, three attacks were thrown back with heavy losses between 4:30 a.m. and 1 p.m. on April 30. Firing from more than a mile away, a German 128mm gun mounted atop the flak tower at the Berlin Zoo inflicted a heavy toll on the Soviets.

Tanks and self-propelled assault guns were brought up to blast the Germans from the rubble of the Reichstag. They clanked into the open space of the Königsplatz and pounded away at point-blank range. At noon, a false report was flashed stating that the red hammer and sickle banner of the Soviet Union was flying above the shattered Reichstag, but in truth the Soviets were still paying in blood for every yard. At the time, they were more or less only halfway across the Königsplatz.

Commanding the 150th Rifle Division, Major General V.M. Shatilov was worried that the premature report of the Reichtag’s capture might reach the higher echelons of Red Army command, perhaps even the Kremlin and Stalin himself. If that happened and the communique was later recognized as inaccurate, Shalitov feared the repercussions—and perhaps his own future. He ordered his soldiers to redouble their effort to take the Reichstag.

As the horrific day wore on, the Soviets tried again and again to dislodge the Reichstag defenders. By 6 p.m., they had been battering the building for 14 hours. At last, intrepid teams moved forward with small mortars to blast open entryways and doors that had been obscured by rubble. Forcing their way inside, the Soviets engaged Germans in a melee of hand-to-hand fighting. Here and there soldiers fought in single combat. The battle raged on every floor, even as a small detachment of soldiers worked its way around to the rear of the building and found an unguarded stairway to the roof. Moments later, Sergeants Meliton Kantaria and Mikhail Yegorov dashed toward an equestrian statue just at the roofline and jammed the red banner into an available space. It was minutes before 11 p.m. local time.

Despite this symbolic victory on the night of April 30, the Reichstag building was still the scene of heavy fighting and was not declared secure until May 2 when 2,500 Germans surrendered, staggering into captivity and an uncertain future. Famous newsreel footage and photographs of the red banner’s raising were staged, actually taken during a reenactment of the triumph on May 3.

On April 30, the hinge of fate swung fatally for the beleaguered defenders of Berlin, running low on ammunition and supplies, exhausted, but holding as they were able. That morning General Weidling informed Hitler that within hours the Red Army would be in control of the center of the city. In the dank netherworld of the Führerbunker, Hitler had already begun preparing for the last macabre act of his 12-year Nazi rule.

While the concussions of Soviet shells shook dust and bits of concrete from the Führerbunker ceiling, he doled out cyanide capsules to the few fanatical loyalists around him and poisoned his Alsatian dog, Blondi, to test their potency. During the night of April 28, he had dictated his two-part last will and testament, a rambling document rife with anti-Semitic drivel blaming the German people for the catastrophic defeat. He blamed the war on international Jewry and declared, “It is untrue that I or anyone else wanted the war in 1939. It was desired and instigated exclusively by those…statesmen who were of Jewish descent or worked for Jewish interests.”

A few minutes after midnight on April 29, Hitler had summoned a low-level Nazi official from the front line to perform a civil service of marriage to his long-time mistress Eva Braun, who refused to evacuate from the bunker. It was a surreal exercise as the two declared their Aryan lineage, and the Führer’s personal secretary Martin Bormann and Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels served as witnesses. During the reception that followed, guests sipped champagne and mused about the most painless and efficient methods of suicide so as not to fall captive to the vengeful Red Army.

At 2:30 a.m. on the 30th, Hitler assembled his staff and muttered goodbyes. He held his final military briefing at noon, useless as it was. He ate his final meal—a vegetarian lunch—two hours later, and spent a few final moments with Bormann, Goebbels, and others of his trusted inner circle. Then, he and Eva retired to their private quarters and committed suicide. Their bodies were carried up the long staircase to the garden of the Reich Chancellery, where a shallow grave was dug, the corpses doused with gasoline and then set alight. The disposition of the bodies was carried out quickly as Soviet artillery shells fell quite close.

The death of the Führer preceded the fall of the Nazi capital by only a few hours. While the drama of Hitler’s demise played out, the Soviet 5th Shock, 8th Guards, and 8th Guards Tank Armies were steadily advancing down the famed Unter den Linden, drawing nearer to the Reich Chancellery and the Führerbunker. Hitler had issued orders to General Weidling to attempt a breakout from the stranglehold, but most of those who scattered were simply on their own. Many died, shot down in the streets. Berliners were subjected to the terror their own troops had wrought in the East—their homes pillaged, old men beaten and murdered, women old and young raped repeatedly.

Retribution had come, a Götterdämmerung that the German people had for so long believed was inconceivable. By the evening of April 30, only about 10,000 German soldiers, sworn to fight to the death, continued to resist the hordes of Red Army troops and tanks that roamed the shattered city. Soviet field guns continually pounded the Air Ministry building on the Wilhelmstrasse, a fortress that had been built intentionally with concrete and steel reinforcement to withstand bombing and ground assault.

Soldiers of the 3rd Shock Army worked their way along the northern edge of the Tiergarten and took on a few German tanks that rallied to oppose them. While they fought the Nazi armor, these troops maintained pressure on the Reichstag building, where fighting was still underway. After destroying the German tanks, elements of the 3rd Shock Army moved in cooperation with the 8th Guards Army and cut the center of Berlin in half.

On May 1, General Hans Krebs, chief of the German Army General Staff, sent a message to General Vasily Chuikov, commander of the 8th Guards Army and a hero of the great victory at Stalingrad in 1942-43, the turning point of World War II on the Eastern Front. Krebs informed Chuikov that Hitler was dead, and he asked for terms of surrender. Chuikov was not charitable. His response was succinct. Nothing other than unconditional surrender would be satisfactory.

Krebs responded that he did not have such authority, and the fighting continued.

At the same time, individual German soldiers or small groups of those trying to save themselves began to abandon their posts, filtering through the ruins of Berlin and hoping to reach the Western Allied lines where they might surrender to the British or Americans and avoid the harsh vengeance of the Soviet troops whose people had suffered so much at the hands of the Nazis earlier in the war. A relative handful of them were successful, some crossing the Havel River at the Charlottenbrücke Bridge, but most met their ignominious fate in a hail of Red Army bullets and artillery shells.

The Reich Chancellery was firmly in Soviet control by the morning of May 2, and in the predawn hours, General Weidling had already sent a communique to Chuikov asking for a meeting to conclude the great battle. Weidling was told to make his way to the Potsdamer Bridge at 6 a.m. He was transported to Chuikov’s headquarters, and within an hour a cease-fire was prepared. At Chuikov’s request, Weidling issued an order for German troops to lay down their arms and wrote that order by hand with pen and paper. He also made a recording of the same instruction, and Soviet trucks blared the message from loudspeakers as they cruised the shattered streets of Berlin.

Even so, there were several pockets of diehard Nazi troops intent on fighting to the death, most of them SS men still under the mad spell of Hitler and Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler. The flak tower at the Berlin Zoo was one of the last scenes of fighting until finally 350 Germans stumbled into the daylight and gave themselves up.

The great Battle of Berlin was over. The Red Army was victorious, but the casualties had been immense. During their drive from the Oder and Neisse to the Nazi capital, at least 81,000 Soviet soldiers had been killed and well over a quarter million wounded in battle. There were scattered reports that in their zeal to please their master, Stalin, rivals Zhukov and Konev had even authorized their troops to fire on one another to gain the upper hand and claim the victory.

Estimates of German losses range as high as 100,000 dead, 220,000 wounded, and nearly a half million taken prisoner. Civilian casualties were horrific, and roughly 100,000 residents of Berlin had died, some by their own hand. For some Germans, the vengeance of the Red Army was, perhaps, a fate worse than death.

In the wake of the Battle of Berlin, the victorious Allied leaders did follow through on their plan to divide Germany into zones of occupation. Berlin, too, was divided, and just as Bradley and Eisenhower had believed, the powers shared in the occupation of the city. In that occupation were sown the seeds of the Cold War and a half century of a nation divided ideologically and territorially between East and West.

Michael E. Haskew is the editor of WWII History magazine. He has written numerous books and articles on military history and resides in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Much has been said of the rape of German Women by the victorious Soviets. Like this was a moral affront that was unjustified. Compared to the brutality inflicted by the Nazis on the peoples they subjugated and invaded there is no compulsion to feel regret or remorse. For their support of the Nazis the deprivations that came as consequences remain as understandable and not troublesome. They deserved far worse than they received.

The abuses committed against the German civilian population were unjustified, just as those committed against the Russian, Belarusian, Ukrainian, etc., civilian population were equally unjustified. I believe that the Nazis should have paid for the crimes committed, but those sanctions should have been applied to those who committed such practices, not against the criminals’ countrymen, just because they were of the same nationality. World War II was a conflict in which the laws of war were completely ignored and violated by many contenders. Unfortunately, it was not the last time that such abuses occurred.